Abstract

Several Shigella flexneri mutants with defects in aromatic amino acid and/or purine biosynthesis have been evaluated as vaccines in humans or in animal models. To be suitable as a vaccine, a mutant has to show virulence attenuation, minimal reactogenicity, and a good immunogenic potential in animal models. With this aim, we have constructed five S. flexneri 5 (wild-type strain M90T) mutants with inactivation of one or two of the loci purEK, purHD, and guaBA, governing early or late steps of purine biosynthesis. The mutants have been analyzed in vitro in cell cultures and in vivo in the Sereny test and in the murine pulmonary model of shigellosis. M90T guaBA, M90T guaBA purEK, M90T guaBA purHD, and M90T purHD purEK gave a negative result in the Sereny test. In contrast, in the murine pulmonary model all of the strains had the same 50% lethal dose as the wild type, except M90T guaBA purHD, which did not result in death of the animals. Nevertheless, bacterial counts in infected lungs, immunohistochemistry, and reverse transcription-PCR analysis of mRNAs for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-12, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) revealed significant differences among the strains. At 72 h postinfection, M90T guaBA purHD still induced proinflammatory cytokines and factors such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS, along with cytokines such as IL-12 and IFN-γ. Moreover, in the absence of evident lesions in murine tissues, this mutant highly stimulated major histocompatibility complex class II expression, showing a significant ability to activate the innate immunity of the host.

Shigellosis is a severe inflammatory diarrhea of humans caused by bacteria of the genus Shigella, of which S. flexneri is the predominant species responsible for endemic shigellosis. There are about 160 millions cases of this disease per year, resulting in more than one million deaths (19). Shigella spp. are invasive bacteria that are able to penetrate and proliferate within human colonic mucosa. In epithelial cell cultures bacterial entry is mediated by the invasion plasmid antigens (IpaB, -C, and -D) (23), which are directly translocated within the cytosol via a type III secretion apparatus (16). Soon after internalization, shigellae lyse the membrane surrounding the phagocytic vacuole, and therefore they can exploit the nutrients present in the cytoplasm of the host cell (36). This leads to the intracellular proliferation of the microorganisms, which migrate from cell to cell through an actin-based motility mechanism (7). Upon bacterial entry, epithelial cells activate NF-κB (31), which in turn induces interleukin-8 (IL-8) production and secretion. In animal models of shigellosis, IL-8 plays a relevant role (34), contributing toward the stimulation of a massive inflammatory response characteristic of natural infections. Inflammation is supported mainly by a polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) influx that destroys intercellular junctions and allows bacteria to access the basolateral pole of epithelial cells, eventually facilitating colonization. However, PMNs are able to kill shigellae (22), in this way limiting bacterial spread to deeper tissues. Following infection with shigellae, macrophages undergo caspase-1-mediated apoptosis, accompanied by IL-1β and IL-18 release (35, 42, 43) that further contributes to the inflammatory reaction (32). In conclusion, shigellae have developed several mechanisms to provoke inflammation in human intestinal tissues. Taking into account this notion, in designing attenuated Shigella mutants to be used as vaccine candidates, the inflammatory potential of the strains should be carefully defined in order to swing the balance between inflammation and immunogenicity toward immunogenicity. In the last few years encouraging progress has been made in this regard, and a number of Shigella vaccine candidates have been constructed and evaluated based on rational attenuation of virulence. These candidates encompass mutants harboring mutations in metabolic pathways (1, 6, 20, 40) and/or mutations in virulence genes (10, 18, 28, 33, 41). The rationale underlying these constructions is to reduce the multiplication of shigellae within the host cells and tissues along with their ability to spread or to induce specific damages. However, despite knowledge of the protective immunity provided by vaccine candidates, current understanding about their virulence phenotypes, in terms of inflammatory potential and ability to stimulate natural immunity, is limited. The integration of this knowledge in a scheme encompassing the virulence profile of a mutant is a critical aspect of the design and improvement of a new generation of live vaccine candidates. With this aim, in this study we have analyzed how the inactivation of different steps of purine biosynthesis alters the virulence phenotype of Shigella. In 1971 a study performed by Formal and coworkers (14) reported that purine-requiring Shigella strains obtained by mutagenesis with N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine retained virulence in spite of their purine dependence for growth. Likewise, it has been shown that adenine auxotrophy slightly reduces Shigella virulence in vivo (9), whereas guanine auxotrophy strongly attenuates virulence in vivo and in vitro (27).

Here we have created five mutants having different levels of attenuation and harboring inactivation of one or two of the following loci: purEK and purHD, whose products control three early steps leading to both IMP and thiamine synthesis, and guaBA, which governs two late steps of GMP synthesis. The virulence of these mutants has been analyzed in vitro in cell culture assays and in vivo in both the Sereny test, which measures the ability of shigellae to induce keratoconjunctivitis in guinea pigs, and the murine pulmonary model of shigellosis. To design a virulence profile of each strain, inflammation-related parameters, including expression and production of cytokines and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (MHC-II) in infected tissues, have been evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely cultured in Trypticase soy broth (BBL, Becton Dickinson and Co., Cockeysville, Md.) or on Trypticase soy agar (TSA). M9 salts (24) were used to prepare minimal medium. Glucose was added at a final concentration of 0.2%, and the medium was supplemented with nicotinic acid (10 μg/ml) to support the growth of shigellae. M9 was also supplemented with hypoxanthine (100 μg/ml), adenine (100 μg/ml), or guanine (100 μg/ml) and B1 (10 μg/ml), required by the strains harboring purHD and/or guaBA mutations. The ability of bacteria to bind the pigment Congo red (Crb phenotype) was assessed by using Trypticase soy agar plates containing 0.01% Congo red dye. When necessary, kanamycin, ampicillin, streptomycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol were added to cultures at 50, 100, 100, 12, and 20 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Growth requirement(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. flexneri 5 | |||

| M90T Smr | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant derivative of wild-type strain M90T harboring pWR100 | Nicotinic acid | 2 |

| ZB2209 | M90T Smr ΔpurHD Kmr | Hypoxanthine, nicotinic acid, B1 | This study |

| ZB501 | M90T Smr ΔguaBA Cmr | Nicotinic acid, guanine | This study |

| ZB502 | M90T Smr ΔguaBA Cmr ΔpurHD Kmr | Nicotinic acid, Guanine, Adenine (Hypoxanthine), B1 | This study |

| ZB503 | M90T ΔpurHD Kmr ΔpurEK | Nicotinic acid, hypoxanthine (adenine), B1 | This study |

| ZB504 | M90T ΔguaBA Cmr ΔpurEK | Nicotinic acid, guanine, adenine | This study |

| E. coli | |||

| DH5α λpir | DH5α (λpir) tet::Mu recA | 8 | |

| SM10 λpir | thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2Tc::Mu (Kmr) λpir | 38 | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pZB216 | pACYC184 containing the full 2.8-kb BamHI-XbaI purHD operon | This study | |

| pZB5102 | pSTBlue-1 carrying a 3-kb fragment containing the guaBA operon | This study |

Genetic procedures.

Conjugation was performed as described by Miller (24). P1 transduction experiments were carried out as previously described (9) according to Miller's procedure (24). Transductants were first selected on the basis of antibiotic resistance. They were analyzed at the molecular level by PCR with primers external to the mutation introduced and in minimal medium for the acquired auxotrophies.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Genomic and plasmid DNAs were prepared with commercial kits (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Enzymes and buffers for recombinant DNA procedures were obtained from Boehringer (Indianapolis, Ind.). DNA electroporation was conducted with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) Gene Pulser. PCR products were cloned by using a Sure Clone ligation kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) or a Perfectly Blunt cloning kit (Novagen, Madison, Wis.).

(i) Construction of M90T ΔpurHD.

A 539-bp fragment, corresponding to the 5′ terminus of the purHD locus, was amplified by using the forward primer AGATCTGTCGTCCAGTCC and the reverse primer GTCGACGCAGTGTGTTCGAAGG. The fragment was digested with BglII and SalI (sites are underlined) and cloned into the suicide vector pGP704 to create pZB213. A 502-bp segment was then amplified from the 3′ terminus of the purHD locus with the forward primer GTCGACGGCAACACCTACA and the reverse primer TCTAGATAGTTCTGCTCGC. The fragment was digested with SalI and XbaI (sites are underlined) and cloned into pZB213. The resulting plasmid, pZB214, was cleaved with SalI between the two fragments and ligated with a 1.2-kb SalI cassette encoding kanamycin resistance from pUC4K to yield pZB215. pZB215 was maintained in DH5α λpir, introduced into Sm10 λpir, and transferred into M90T Smr by conjugation. Transconjugants were selected on kanamycin agar plates and screened for ampicillin sensitivity. They were expected to be produced through double allelic exchange between the 5′ and 3′ fragments cloned into pZB215 and the corresponding regions on the M90T chromosome. Transconjugants were also checked for the acquired hypoxanthine and B1 auxotrophies on M9 agar plates. Kmr, Aps, and Crb+ mutants and thiamine and hypoxanthine auxotrophs were subjected to PCR and sequence analysis.

(ii) Construction of M90T ΔguaBA.

Two DNA fragments, of 646 bp (fragment 1) and 781 bp (fragment 2), of the S. flexneri 5a guaB and guaA genes, respectively, were amplified by PCR with the following primers: guaBF (5′-GCTCTAGAACCGTTCTGCCGAATACTGCTGAC-3′) and guaBR (5′-TGCACTGCAGCGCGTCAACACGCTCTTCGTTACC-3′) for fragment 1 and guaAF (5′-TGCACTGCAGCGTGCGTGAGCTGGTGTTTACTG-3′) and guaAR (5′-CGGAATTCCAATGTTAAGACCAAAGTGATCGCC-3′) for fragment 2. The fragments were digested with XbaI and PstI (fragment 1) and PstI and EcoRI (fragment 2) (sites are underlined), ligated with an 829-bp PstI cassette encoding chloramphenicol resistance from pGEM-CAT (a gift from A. Covacci, Chiron Vaccines, Siena, Italy), and cloned into the XbaI-EcoRI sites of the suicide vector pGP704 to create pZB5101. Plasmid pZB5101 was transferred into M90T Smr by conjugation, and transconjugants were selected on chloramphenicol agar plates, screened for ampicillin sensitivity as described above, and checked for the acquired guanine auxotrophy on M9 agar plates. Cmr, Aps, and Crb+ mutants and guanine auxotrophs were subjected to PCR and sequence analysis.

(iii) Cloning of Shigella purHD and guaBA loci.

To clone the purHD operon, a fragment of 2.8 kb containing the complete sequences of purH and purD was amplified from M90T genomic DNA with the forward primer AGATCTGTCGTCCAGTCC and the reverse primer TCTAGATAGTTCTGCTCGC. The amplified DNA was digested with BglII and XbaI (sites are underlined) and ligated into the BamHI-XbaI sites of pACYC184 to create pZB216.

To clone the guaBA locus, a fragment of 3.0 kb containing the complete sequences of guaB and guaA was amplified from the M90T genomic DNA by using the forward primer 5′-ATGCTACGTATCGCTAAAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-TCATTCCCACTCAATGGTAG-3′. The amplified DNA was cloned into pSTBlue-1 blunt vector (Perfectly Blunt cloning kit; Novagen) to create pZB5102. The cloning of the purHD and guaBA operons was verified (i) at the molecular level through PCR analysis and (ii) at the phenotypic level through transcomplementation of the purHD deletion in M90T ΔpurHD and of the guaBA deletion in M90T ΔguaBA in unsupplemented M9 minimal medium.

Virulence assays. (i) HeLa cell culture conditions.

Cells were maintained in minimal essential medium (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with fetal calf serum (HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, Utah) at a concentration of 10%.

(ii) Intracellular multiplication.

Multiplication of bacteria was assayed at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 5, 10, and 100 on nonconfluent monolayers of HeLa cells (105/ml) on 35-mm-diameter dishes as previously described (9).

(iii) Plaque assay.

The plaque assay was carried out as described previously (9) at MOIs of 1, 10, and 100.

(iv) Sereny test.

The keratoconjunctivitis assay in guinea pigs was performed as described previously (15) with two challenges, 108 and 109 CFU. The degree of keratoconjunctivitis was ranked on the basis of time of development, severity, and (when possible) rate of clearance of symptoms, with the following scores: 0, no disease; 1, mild conjunctivitis; 2, keratoconjunctivitis with no purulence; and 3, fully developed keratoconjunctivitis with purulence.

(v) Intranasal infection of mice.

Five-week-old BALB/c female mice (Charles River, Calco, Italy) were anesthetized intramuscularly with 50 μl of a solution containing Zoletil (1 mg) (Virbac, Carros, France) and Xilor (2%) (BIO 985, San Lazzaro, Italy) and inoculated intranasally with 20 μl of 0.9% NaCl suspensions containing 108 CFU of each strain (21). After 72 h, mice were euthanatized by cervical dislocation and lungs were removed and processed for histopathological studies, bacterial counts, and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis. For bacterial counts, 5 ml of saline buffer was added to samples that were immediately stored in ice. Samples were then ground with an Ultraturrax apparatus (Janke and Kunkel, GmbH, and Co., Staufen, Germany). Serial dilutions of the resulting solutions were plated on Congo red agar plates supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic(s). Lungs processed for RT-PCR were removed after having been extensively washed with 10 ml of saline solution introduced through the right atrium of the heart and then were immediately frozen in liquid N2. Ten mice were used per group, and experiments were repeated twice.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

For routine histology and immunohistochemistry, lung samples were removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections, 3 μm thick, were stained with hematoxylin-eosin or processed for immunohistochemistry. For the immunohistochemical study, lung sections were allowed to adhere to pretreated slides (Bioptica S.p.A., Milan, Italy) and then deparaffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase activity was removed by incubation with 0.5% hydrogen peroxide in distilled water for 1 h at room temperature. The primary monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) employed were the following: a rat anti-mouse MHC-II MAb (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom), a rat anti-mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) MAb (Serotec), and a murine anti-S. flexneri 5a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) MAb (6 mg/ml) (30). Tissue sections were incubated overnight in a moist chamber at 4°C with different primary antibodies diluted 1:100 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% crystalline bovine serum albumin. A 1:200-diluted biotinylated rabbit anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) and a 1:200-diluted biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (AO433; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) were applied for 45 min at room temperature as secondary antibodies. After two 5-min rinses with TBS, tissue sections which had been incubated with anti-S. flexneri LPS or with anti-TNF-α MAb were incubated with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories) diluted 1:50 for 45 min at room temperature. Sections treated with anti-MHC-II primary MAb were incubated with the avidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complex (Vector Laboratories) under the same conditions. The immunoreactions were then revealed by using either the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Chemicals Co.) or Vector red (Vector Laboratories) as chromogens for the sections incubated with avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex and for those incubated with avidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complex, respectively. Sections were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Specific primary antibodies replaced with TBS or nonimmune sera were used as negative controls in immunohistochemical techniques.

Histological examination included assessment of inflammation by scoring the number of inflammatory cells (mononuclear cells, such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, and neutrophils) at a magnification of ×400. The number of inflammatory cells was evaluated by using a visual analogue scale modified for murine pulmonary specimens, and results are reported as the mean for the entire specimen. When considerable variation of intensity of infiltration was evident in the same specimen, the mean for several areas was determined and the specimen was scored accordingly. Neutrophils and mononuclear cells were classified as absent (score of 0) when there were no or fewer than 5 cells per high-power field (HPF) (at a magnification of ×400), mild (score of 1) for 5 to 19 per HPF, moderate (score of 2) for 20 to 49 cells per HPF, marked (score of 3) for 50 to 99 cells per HPF, and severe (score of 4) for 100 to 200 cells or more per HPF.

Histological criteria for normal pulmonary characteristics included detection of no or only a few mononuclear cells per HPF and no or only a few scattered neutrophils in bronchioli and alveoli without tissue changes (no interstitial thickening or bronchiolar-associated lymphoid tissue [BALT] activation and airways free from exudate).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA from homogenized lungs was extracted by using Trizol solution (Invitrogen, S. Giuliano Monzese, Italy) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNase-free DNase (Boehringer Mannheim) was used to remove genomic DNA as described by Dilworth and McCarrey (13). RT of total RNA (1 μg) and cDNA PCR were performed by using the SuperScript one-step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's manual. PCR with primers for β-actin was performed on each individual sample as an internal positive-control standard. As a negative control, PCR without cDNA (with water as the substitute) was run concurrently. Cytokine mRNAs were quantitated by using Quantity-One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and results were normalized to the amount of β-actin mRNA. The median value from three runs was used to estimate mRNA levels for individual mice.

RESULTS

Construction of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK).

To obtain a Shigella mutant with a deletion in the purHD locus, encoding 5′-phosphoribosylglycinamide synthetase and 5′-phosphoribosyl-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboaxamide transformylase-IMP-cyclohydrolase, the purHD operon was cloned, mutagenized in vitro, and reintroduced into the M90T genome. As expected, the resulting strain, ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD Km), did not grow on minimal medium in the absence of hypoxanthine and B1. Likewise ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA Cm), which is unable to synthesize IMP dehydrogenase and guanosine synthetase, was constructed through double allelic exchange between the wild-type guaBA locus on the M90T chromosome and a guaBA copy mutagenized in vitro. ZB501 did not grow on minimal medium without guanine. Transcomplementation of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) with the proficient purHD operon cloned into pZB216 and of ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) with the functional guaBA operon cloned into pZB5102 restored the ability of both mutants to grow on unsupplemented minimal medium.

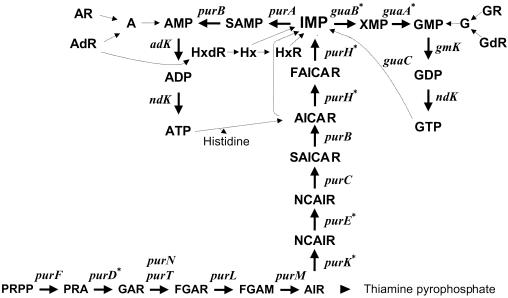

To stress purine auxotrophy in M90T we created three other mutants with defects in purine biosynthesis in addition to ZB501 and ZB2209. A strain was obtained by transducing the purHD Km mutation from ZB2209 into ZB501. This mutant, ZB502, carried a deletion of both operons guaBA and purHD. We had previously constructed an M90T strain, ZB2106, harboring a deletion of the purEK locus encoding phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase (9). This strain showed minimal attenuation in vivo. Therefore, the purHD Km deletion was transferred by P1 transduction from ZB2209 to ZB2106, giving ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK). Likewise, the guaBA Cm mutation was transduced into ZB2106 (M90T ΔpurEK), resulting in ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK). The mutants are listed in Table 1, and Fig. 1 summarizes the relevant steps of purine biosynthesis and the relative positions of enzymatic steps performed by the enzymes deleted in the mutants constructed in this study.

FIG. 1.

Purine de novo biosynthesis pathway and essential steps of purine salvage and interconversion. The individual enzymes are identified by their gene symbols. Solid lines indicate de novo biosynthesis; dotted lines represent purine salvage and interconversion. The arrowhead represents pathways in which the individual steps are not shown. Asterisks indicate mutations introduced in the S. flexneri 5 wild-type strain M90T. Abbreviations: PRA, 5′-phosphoribosylamine; GAR, 5′-phosphoribosylglycinamide; AIR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-5-aminoimidazole; NCAIR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-5-carboxyaminoimidazole; CAIR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxylic acid; AICAR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-4-carboxamide-5-aminoimidazole; FAICAR, 5′-phosphoribosyl-4-carboxamide-5-formamidoimidazole; Hx, hypoxanthine; R and dR, ribonucleosides and deoxyribonucleosides, respectively.

Invasion ability, intracellular multiplication, and dissemination of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK).

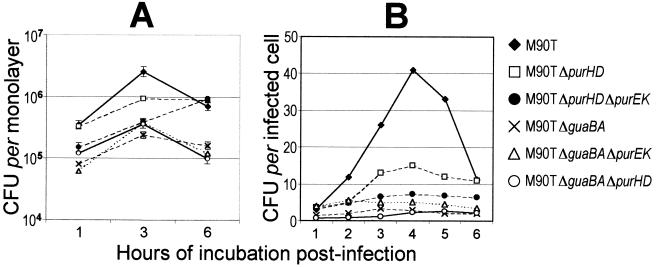

The intracellular multiplication kinetics of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) were analyzed within HeLa cell monolayers. The strains were assessed for intracellular proliferation within 6 h of infection. The results are shown in Fig. 2. At an MOI of 100, by evaluating the number of bacteria per monolayer the mutants appeared to be impaired in intracellular proliferation to various extents depending on the mutation(s) introduced (Fig. 2A). This difference became more evident when the MOI was lowered to 10 and the multiplication kinetics per infected cell rather than per monolayer were analyzed (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Intracellular growth kinetics of M90T, ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) during incubation for 6 h p.i. (A) Means (± standard deviations) of the numbers of bacteria calculated in five separate invasion assays. (B) Data from one representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in three identical invasion assays. Standard deviations were within 20% of the values presented.

Although intracellular proliferation of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) was reduced compared with that of M90T, the association of purHD and purEK made ZB503 (M90T ΔpurEK ΔpurHD) unable to proliferate intracellularly. Mutants harboring the guaBA inactivation, i.e., ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) all showed the same kinetics, characterized by (i) a reduced ability to penetrate HeLa cells and (ii) a significant decrease in the ability to proliferate intracellularly.

The proportion of infected cells after 1 h of incubation postinfection (p.i.) was 59.3% ± 21.1% for M90T and 15.0% ± 4.2% for ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), obtained in four different experiments with a minimum of 500 cells counted per sample. With ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK), we obtained percentages of infected cells similar to those for the parent strain ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), i.e., 19.2%. ± 5.7% and 17.9% ± 2.9%, respectively. In contrast, ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) and ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) behaved like the wild-type strain, with values of 51.9% ± 11.1% and 48.7% ± 15.3%, respectively. During the first 4 h of invasion, the number of intracellular M90T organisms roughly increased 10-fold, whereas that of the mutants harboring the guaBA mutation hardly increased 3-fold. Findings concerning the mutants carrying the guaBA deletion are consistent with those previously reported by Noriega and coworkers (27) for an S. flexneri 2a guaBA mutant and point to both an impaired ability to invade and an altered ability to grow as the major effects of this mutation in Shigella.

The ability of ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) to spread intra- or intercellularly was determined from the following data: (i) actin tails were produced within the infected cells as assessed through nitrobenzoxadiazole-phalloidin labeling of polymerized ctin (data not shown), and (ii) an increasing number of HeLa cells were infected during 6 h of cell invasion in the presence of gentamicin, which is assumed to prevent cell reinfection by extracellular bacteria.

The mutants were also assessed by the plaque assay, which covers at least three parameters: the invasion ability, the intracellular multiplication, and the intra- and intercellular movement and cytotoxicity, resulting in a cytopathic effect observable as areas of cell death on the confluent monolayer. ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) were assessed in the plaque assay at MOIs of 100, 10, and 1. Two mutants, ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) and ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), produced plaques smaller than those of M90T. In particular, plaques produced by ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) were roughly 50%, and those by ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) were about 10%, of the size of plaques produced by M90T, albeit for the latter only at an MOI of 100. ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) did not produce plaques at all. ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD)(pZB216) had its ability to produce plaques of a size comparable to those of M90T restored, and intracellular proliferation reverted consistently to the wild-type values. Likewise, transcomplementation of ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) with pZB5102 reestablished the ability of this strain to proliferate within HeLa cell monolayers and to provoke a positive plaque assay at MOI 1. ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA purHD) was restored to full virulence only by the concomitant presence of the proficient purHD and guaBA operons cloned into pZB216 and pZB5102, respectively. Likewise, ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK)(pZB216) and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK)(pZB5102) entered and proliferated within HeLa cells and gave the same positive result in the plaque assay as the wild-type strain.

Sereny test.

ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) were analyzed in the Sereny test with two challenges of 108 and 109 CFU. With ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) at 108 CFU, the reaction was weaker than that produced by M90T, and symptoms were delayed by 24 h. At the higher inoculum, however, the intensity of keratoconjunctivitis was similar to that with M90T even though the appearance of symptoms was delayed by about 24 h. ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD)(pZB216) induced reactions of the same intensity as M90T. Timing of symptom appearance was also similar to that for wild-type organisms. ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) gave a negative result in this test at any challenge dose. The results are shown in Table 2. ZB501(pZB5102), ZB502(pZB216, pZB5102), ZB503(pZB216), and ZB504(pZB5102) were Sereny positive at both challenge doses. ZB502(pZB216) was Sereny negative whereas ZB502(pZB5102) behaved like ZB2209 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Assessment of virulence of the mutants in the murine pulmonary model of shigellosis and the Sereny test

| Strain | Murine pulmonary model

|

Sereny test rating of keratoconjunctivitisc at the following inoculum (bacteria ml−1):

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortalitya (%) | Mean CFU in lungs ± SDb (103) | 108 | 109 | |

| M90T | 50 | 1,600 ± 720 | 3 | 3 |

| ZB2209 (ΔpurHD) | 60 | 9.9 ± 1.02 | 2d | 3d |

| ZB501 (ΔguaBA) | 60 | 0.1 ± 0.07 | 0 | 0 |

| ZB502 (ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) | 0 | <50 | 0 | 0 |

| ZB503 (ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) | 60 | 1 ± 0.64 | 0 | 0 |

| ZB504 (ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) | 50 | 1 ± 0.19 | 0 | 0 |

Twenty mice per strain were infected intranasally with 108 bacteria, and the LD50 was obtained at 72 h p.i.

Surviving animals were sacrificed at 72 h p.i., and lungs were removed and tested for bacterial counts.

Results were evaluated at 72 h postchallenge. The degree of keratoconjunctivitis was rated on the basis of time of development, severity, and (when possible) rate of clearance of symptoms, with the following scores: 0, no disease; 1, mild conjunctivitis; 2, keratoconjunctivitis with no purulence; 3, fully developed keratoconjunctivitis with purulence (15).

Symptoms were delayed for 24 h.

Intranasal infection of mice.

The mutants were analyzed in the murine pulmonary model of shigellosis (21). Twenty mice were infected with 108 microorganisms per strain and inspected daily. At 72 h postchallenge, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) was reached with M90T. At this time point, surviving mice were sacrificed and lungs were removed for bacterial counts, RT-PCR, and histopathological analyses. Mortality and bacterial counts were recorded (Table 2). After 72 h of infection 50 to 60% of the animals infected with ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) died. Lungs removed from the survivors contained from 102 to 104 bacteria, depending on the strain. Surprisingly, no animal died upon the infection with ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA purHD), and no bacteria (<50 bacteria/organ) were found in lungs after 72 h. When either ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD)(pZB216), ZB502(pZB5102), or ZB502(pZB216, pZB5102) was used to infect mice, the LD50 was reached after 72 h as for M90T and the other mutants. This analysis clearly revealed that the purHD and the guaBA deletions together drastically attenuate M90T virulence and differentiate the corresponding mutant, ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA purHD), from the others used in this study.

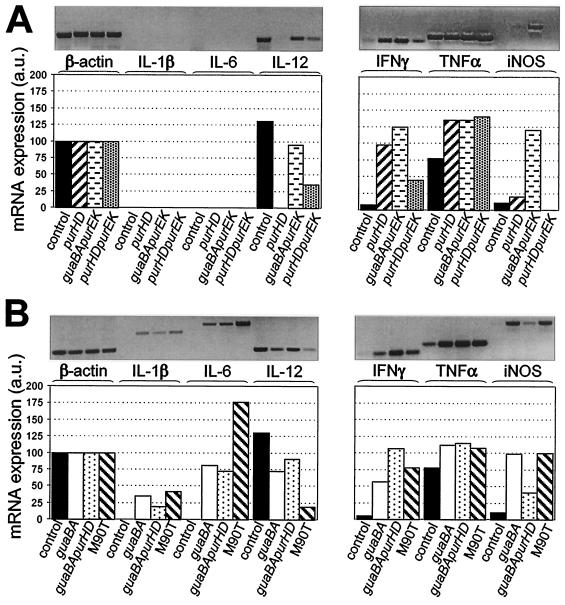

Expression of cytokines in lungs.

To obtain major insight into the inflammatory potential of these strains, the expression of relevant cytokines in lungs of mice infected with M90T and the mutants was investigated by RT-PCR. We analyzed the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and iNOS after 72 h of infection. Table 3 details the primers used and the size of the fragments expected, and Fig. 3 shows the results obtained. In uninfected lungs, only the expression of TNF-α, IL-12, iNOS, and IFN-γ was detectable, to different degree. All strains induced a relevant increase of TNF-α, while the expression of the other cytokines was variable depending on the mutant. In lungs of animals infected with M90T, we observed a moderate increase of mRNAs for IL-1β and iNOS along with a decrease of mRNA for IL-12. Another relevant finding was the large amount of IL-6, consistent with the production of this cytokine in the course of pulmonary shigellosis (30), and the augmentation of mRNA for IFN-γ. Conclusively, M90T seems to trigger a significant increase of proinflammatory cytokine expression along with a stimulation of the innate immune response characterized mainly by IFN-γ mRNA synthesis. The patterns of the cytokines expressed by the mutants may be roughly classed in two groups. The first group includes ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK); in tissues infected with these mutants, IL-1β and IL-6 were not expressed, and mRNA for IL-12 was absent with ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD), scantly produced with ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK), and significantly produced with ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK). The level of TNF-α was high, that of iNOS was low or null with the exception of ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK), and that of IFN-γ was higher with ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) than with ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK). The second group includes the mutants ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) and ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD). Infections with these strains were characterized by weak levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and by good production of mRNA for IL-12. Both strains induced the expression of mRNA for IFN-γ, even though the amount of IFN-γ mRNA found in tissues infected with ZB502 was roughly double that found with ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA). By contrast, ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) stimulated a weaker production of iNOS than ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA).

TABLE 3.

Primers used in RT-PCR analysis

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′→3′) | RT-PCR product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| β-Actin I | TGG AAT CCT GTG GCA TCC ATG AAA C | 348 |

| β-Actin II | TAA AAC GCA GCT CAG TAA CAG TCC G | |

| IL-1β I | TCA TGG GAT GAT GAT GAT AAC CTG CT | 502 |

| IL-1β II | CCC ATA CTT TAG GAA GAC ACG GAT T | |

| IL-6 I | CTG GTG ACA ACC ACG GCC TTC CCT A | 600 |

| IL-6 II | ATG CTT AGG CAT AAC GCA CTA GGT T | |

| IL-12 I | CGT GCT CAT GGC TGG TGC AAA G | 312 |

| IL-12 II | CTT CAT CTG CAA GTT CTT GGG C | |

| IFN-γ I | AGC GGC TGA CTG AAC TCA GAT TGT AG | 243 |

| IFN-γ II | GGC AGG TCT ACT TTG GAG TCA TTG C | |

| TNF-α I | GGC AGG TCT ACT TTG GAG TCA TTG C | 307 |

| TNF-α II | ACA TTC GAG GCT CCA GTG AAT TCG G | |

| iNOS I | ACG CTT GGG TCT TGT TCA CT | 468 |

| iNOS II | GTC TCT GGG TCC TCT GGT CA |

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR and densitometry of products of RNAs extracted from lungs of three mice infected with either M90T or mutants, using primers specific for β-actin, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and iNOS at 72 h p.i. (A) Control, uninfected control lung; purHD, ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD); guaBA purEK, ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK); purHD purEK, ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK). (B) Control, uninfected control lung; guaBA, ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA); guaBA purHD, ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD). Similar results were obtained in three identical experiments. Standard deviations for three experiments were within 10% of the values of the arbitrary units (a.u.).

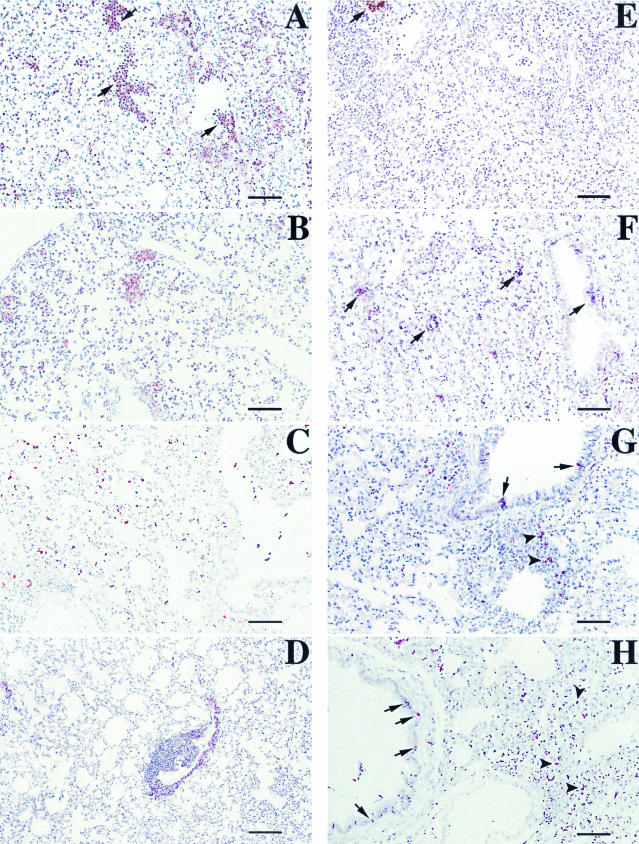

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry of lungs infected with M90T and the mutants.

Histopathological analyses were performed on tissue sections from lungs of animals sacrificed after 72 h p.i., and alterations were quantified and recorded as the means of different scores that indicated the degree of alveolar septum thickening, infiltration and diffusion of neutrophils in alveolar spaces, presence of monocytes, degree of bronchiolar inflammation and epithelial damage, and degree of BALT activation on hematoxylin-eosin-stained tissue sections. These data are shown in Table 4. In addition to morphological evaluations, sections treated with different MAbs were evaluated for the degree of MHC-II, TNF-α, and LPS expression. The wild-type strain M90T caused maximal lesions, characterized by the highest scores, due to a large area of severe suppurative bronchopneumonia in which bronchioles and immediately adjacent alveoli were filled with neutrophils and sometimes with an admixture of various amounts of cell debris, mucus, and macrophages (Fig. 4A), with strong reduction of air-filled areas of parenchyma. At the same time, strong expression of TNF-α and few MHC-II-positive cells were seen (Fig. 5A and E). LPS expression was strong and diffuse, with the presence of the antigen both in inflammatory cells and free in the mucus (Fig. 6A). The mutants ZB2209 (M90T ΔpurHD) and ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) showed a similar pattern of inflammation and expression of the different antigens employed, although minor lesions were observed in mice infected with ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) (Fig. 4B and 5B and F). With the latter mutant, LPS was abundant, and its localization was maximal inside mononuclear cells (Fig. 6B). Intermediate values of phlogosis were observed in mice infected with the mutant ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), with which a different pattern of inflammatory reaction was observed, characterized by a low level of neutrophils in air spaces and moderate BALT activation associated with severe thickening of alveolar septa (Fig. 4C). In ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA)-infected lungs, weak TNF-α expression was observed (Fig. 5C), in contrast to the high number of the MHC-II-positive cells (Fig. 5G). In the same manner, low levels of LPS were observed, and the expression of the antigen was restricted to the cytoplasm of mononuclear cells constituting the BALT aggregates. Finally, the mutants ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) and ZB504 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) showed a dramatic decrease in the pattern of pathology. In particular, in lungs infected with the ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) mutant, the alveolar septa and airways in general remained similar to those observed in control, uninfected organs. An interesting observation was the very strong reaction of BALT and, only in lungs infected with this strain, the development of characteristic perivascular cuffing (Fig. 4D). In the same samples, immunostaining to MHC-II revealed the highest number of positive cells, compared to a weak positivity for TNF-α antigen (Fig. 5D and H). As observed in lungs infected with ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA), with ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) LPS expression was essentially localized in macrophages, resident or recruited as monocytes, constituting vascular cuffing and BALT aggregates (Fig. 6C).

TABLE 4.

Histological examination of murine lungs infected with S. flexneri wild-type strain M90T and its mutants

| Strain | Interstitiuma | Intralveolar desquamationb | Intrabronchial materialc | Polymorphonuclear cellsd | Mononuclear cellsd | BALTe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M90T | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| ZB2209 (ΔpurHD) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| ZB501 (ΔguaBA) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ZB502 (ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| ZB503 (ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| ZB504 (ΔguaBA ΔpurEK) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

Degree of thickening of interalveolar septa due to inflammatory edema.

Degree of broncho- and bronchiolar epithelium desquamation and necrosis.

Degree of mucopurulent exudate, i.e., cellular debris, polymorphonuclear cells, and proteinaceous material observed in airways.

Scored as cells per HPF at a magnification of ×400: 0, fewer than 5 cells; 1, 5 to 19 cells; 2, 20 to 49 cells; 3, 50 to 99 cells; 4, more than 100 cells.

Degree of activation of BALT, i.e. presence and size of clear center and follicular structuration of BALT aggregates.

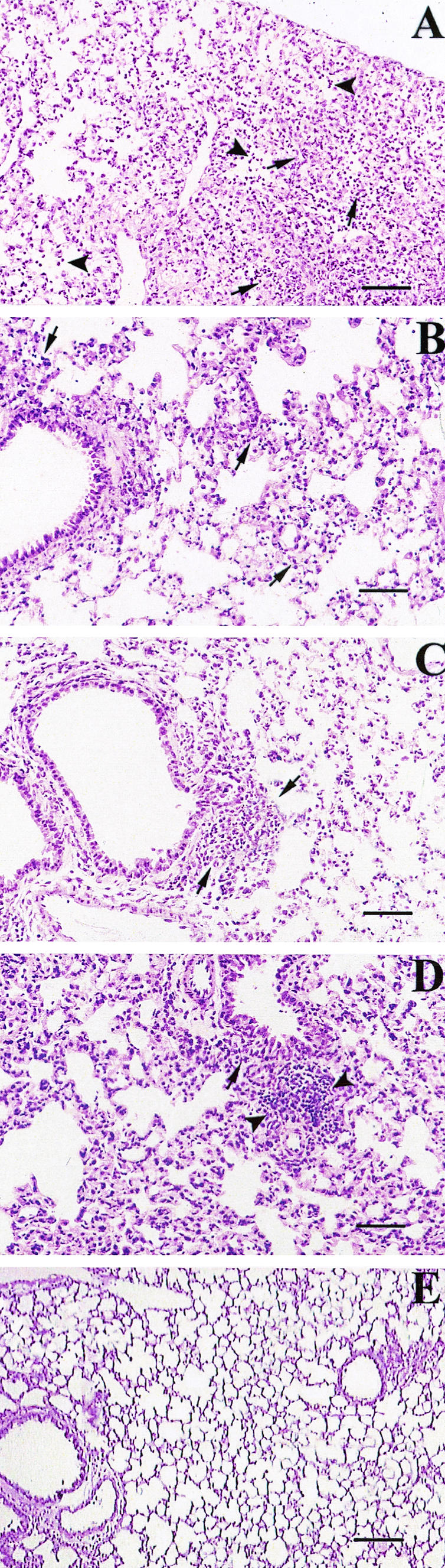

FIG.4.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining of tissue sections of lungs of mice infected with M90T (A), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) (B), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) (C), and ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) (D) at 72 h p.i. and of uninfected control mice (E). (A) The lung section shows severe suppurative bronchopneumonia characterized by cellular exudate filling alveolar spaces and airways in the absence of BALT activation. Arrows point to alveolar spaces filled with PMNs. (B) Arrows point to some alveolar spaces with moderate degrees of PMN infiltration. (C) Mild phlogosis is observable; arrows indicate areas of moderate BALT activation. (D) Alveolar spaces and airways are free from inflammatory cells; the arrow indicates an area of strong BALT reaction, and arrowheads point to a characteristic perivascular cuff. (E) The uninfected control shows a normal lung section; note the absence of inflammatory infiltrates, the thin aspect of alveolar septa, and the absence of BALT activation or perivascular cuffs. Bars, 50 μm.

FIG. 5.

Avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase labeling of TNF-α (A, B, C, and D) and of MHC-II complexes (E, F, G, and H) in tissue sections of lungs of mice infected with M90T (A and E), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) (B and F), ZB501 (M90T ΔguaBA) (C and G), and ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) (D and H) at 72 h p.i. In panel A arrows point to high expression of TNF-α in neutrophil aggregates, in panels E and F arrows indicate a few MHC-II-expressing cells, in panel G arrows point to some MHC-II-expressing bronchiolar cells and arrowheads point to BALT MHC-II-positive cells, and in panel H some bronchiolar mucosal and mononuclear MHC-II-expressing cells are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. Bars, 25 μm (A, B, C, and D) and 50 μm (E, F, G, and H).

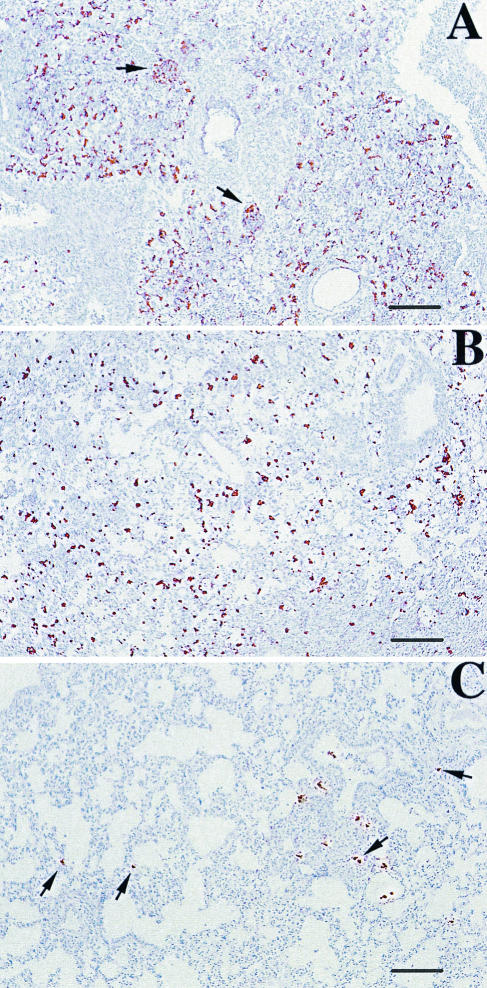

FIG. 6.

Avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase labeling of serotype 5 somatic antigen by anti-LPS monoclonal immunoglobulin A of tissue sections of lungs of mice infected with M90T (A), ZB503 (M90T ΔpurHD ΔpurEK) (B), and ZB502 (M90T ΔguaBA ΔpurHD) (C) at 72 h p.i. In panel A arrows point to some of the several areas showing a diffuse LPS positivity, in panel B LPS is mainly concentrated inside mononuclear cells, and in panel C arrows indicate the rare but strong and macrophage-localized presence of LPS. Bars, 25 μm.

DISCUSSION

Auxotrophic mutants may be defective in those virulence phenotypes that are influenced by the growth impairment whenever the required metabolites are present in insufficient amounts in the host compartment where the bacteria reside. As a consequence, the virulence and immunogenicity of these mutants are difficult to predict a priori. Starting from these premises, in this study we have tried to analyze how the absence of some enzymatic functions, governing key steps in purine biosynthesis, alters the interplay between Shigella and the host's cells and tissues.

In Escherichia coli the requirement for IMP, a key intermediate in adenine and guanine biosynthesis, may be satisfied by hypoxanthine, which, through the purine salvage pathway and interconversion, is transformed into both AMP and GMP (29) (Fig. 1). In contrast, the absence of enzymes participating in steps beyond IMP, such as those governed by the products of guaBA locus, could impair the virulence of pathogenic bacteria that have to scavenge preformed purines to fulfill their requirements. In agreement with this theory, it has been reported that an S. flexneri 2a ΔguaBA mutant was highly attenuated in vitro as well as in vivo (27). The data reported in this study indicate that deletion of the purHD locus, leading to IMP synthesis, moderately attenuates Shigella virulence in that this strain exhibits a lower ability to proliferate intracellularly and probably in host tissues. In contrast, the deletion of the guaBA locus renders the S. flexneri 5 guaBA mutant, M90T guaBA, severely attenuated. In this case, attenuation is based on two altered behaviors: first, impairment in growth, and second, as previously reported (27) for the S. flexneri 2 guaBA mutant, the unexpected reduced ability to invade epithelial cells. Therefore, the relevant attenuation of M90T guaBA and its ability to stimulate the immune potential results from a synergistic effect of these two defects. The ability of M90T guaBA to invade cell culture monolayers and virulence were reestablished by the introduction of a functional copy of this locus, demonstrating that attenuation of this mutant directly relies on the absence of the guaBA products.

In the pulmonary model of shigellosis, M90T purHD, M90T guaBA, M90T purHD purEK, and M90T guaBA purEK, have roughly the same LD50 as the wild-type strain, while M90T purHD guaBA did not cause death of the animals. Nevertheless, major differences were observed in the inflammatory potential of these mutants and in their persistence within lungs. TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS are considered the main mediators of inflammation following exposure of host tissues to LPS. In particular, TNF-α is assumed to be one of the principal molecules responsible for lesions in tissues infected either naturally or experimentally with Shigella (12), and high concentrations of TNF-α have been found in the stools of patients with shigellosis (11) and in intestinal fluid of ligated ileal loops of experimentally infected rabbits (12). In agreement with these data, all of the strains induced strong TNF-α mRNA synthesis; however, M90T and to a lesser extent M90T purHD induced a massive, widely diffused TNF-α production, whereas mutants harboring the guaBA inactivation, particularly M90T guaBA purHD, provoked a localized distribution of this molecule in the areas of BALT aggregates. At the time point analyzed, i.e., after 72 h p.i., only M90T, M90T purHD guaBA, and M90T guaBA still induced a small amount of IL-1β mRNA and IL-6 mRNA. Moreover, iNOS production, assessed through iNOS mRNA quantification, which is assumed to have a beneficial effect in host defense mechanisms against various pathogenic bacteria (26), was present in lungs infected with M90T and mutants with guaBA inactivation. However, despite the residual expression of these mediators associated with inflammation, the lesions observed in tissues infected with the strains harboring guaBA inactivation and M90T were completely different. As already described (30, 39), M90T induces wide areas of necrosis characterized by the massive presence of PMNs, whereas in lungs infected with either M90T guaBA purEK, M90T guaBA purHD, or, to a lesser extent, M90T guaBA, the architecture of the tissue remained essentially unaffected, consistent with the small amount of neutrophils present in alveolar spaces. Interestingly, in tissues of animals that received M90T guaBA purEK or M90T guaBA purHD, a significant presence of monocytes was observed along with BALT reaction. BALT activation might be responsible for the high levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 found with the guaBA mutants and particularly with M90T guaBA purHD. These data taken together indicate that the association of these two mutations, guaBA and purHD, might stimulate a Th1 response. This would be consistent with the cytokine pattern obtained in humans during immunization with a S. flexneri 2 vaccine with virG, sen, set, and guaBA inactivation (18), which is characteristic of a Th1 response.

In addition to the presence of cytokines and costimulatory signals, Th1/Th2 dichotomy may be influenced by the density of peptide-MHC complexes on antigen-presenting cells (25). A wide diffuse presence of MHC-II was detected in tissues of animals infected with M90T guaBA purHD or M90T guaBA purEK and not in those of animals that had received M90T, despite the high number of bacteria found in the lungs. Conclusively, our results point out the immune potential of these two strains and support the hypothesis that infections with these mutants might influence the Th1/Th2 outcome.

Shigella subverts host defenses by inhibiting macrophage presentation of antigens and eventually inducing apoptosis of this cell population (37, 42). We found that in the absence of live bacteria (<50 bacteria) in lungs of animals that had received M90T guaBA purHD, the presence of LPS was scattered but intense and was mainly associated with macrophages or monocytes located in BALT or in vascular cuffings. In contrast, the LPS distribution in lungs infected with M90T was diffuse and organized in large patches consistent with the high bacterial counts. These results suggest that bacterial material from M90T guaBA purHD may persist in BALT, acting as an antigen stimulating antigen-presenting cells and lymphocytes and thereby favoring the switch from innate to adaptive immunity.

Vaccines harboring the inactivation of the guaBA operon have provided encouraging results in terms of protection and immunogenicity as Shigella vaccine candidates (4, 18) and as Shigella-based vaccine vectors (3, 4, 5, 17). Our results indicate that the association of this mutation with purEK or, better, with purHD in M90T guaBA purEK and M90T guaBA purHD strengthens the virulence attenuation, along with the immunopotential of the double mutants with respect to M90T guaBA. Therefore, the combination of these mutations might improve the immunogenicity provided by the introduction of the guaBA mutation in Shigella.

To switch to a new generation of Shigella vaccines, it might be beneficial to investigate on the qualitative differences in host responses elicited by the individual genetic defects. This might constitute the basis for a list of mutations whose characterization would allow their rational association in vaccine candidates useful for various medical purposes in which a targeted immunomodulation is desired.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge G. Cohen and M. Mavris for careful reading of the manuscript and useful comments.

This work was supported by a grant from the European Union (QLK2-1999]00938).

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, Z. U., R. S. Mahfuzur, and D. A. Sack. 1990. Protection of adult rabbits and monkeys against shigellosis by oral immunization with a thymine-requiring and temperature-sensitive mutant of Shigella flexneri Y. Vaccine 8:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allaoui, A., J. Mounier, M.-C. Prévost, P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1992. icsB: a Shigella flexneri virulence gene necessary for the lysis of protrusions during intercellular spread. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1605-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altboum, Z., E. M. Barry, G. Losonsky, J. E. Galen, and M. M. Levine. 2001. Attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a ΔguaBA strain CVD 1204 expressing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) CS2 and CS3 fimbriae as a live mucosal vaccine against Shigella and ETEC infection. Infect. Immun. 69:3150-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, R. J., M. F. Pasetti, M. B. Sztein, M. M. Levine, and F. R. Noriega. 2000. ΔguaBA attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204 as a Shigella vaccine and as a live mucosal delivery system for fragment C of tetanus toxin. Vaccine 18:2193-2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry, E. M., Z. Altboum, G. Losonsky, and M. M. Levine. 2003. Immune responses elicited against multiple enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli fimbriae and mutant LT expressed in attenuated Shigella vaccine strains. Vaccine 21:333-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardini, M. L., J. Arondel, I. Martini, A. Aidara, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2001. Parameters underlying successful protection with live attenuated mutants in experimental shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 69:1072-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernardini, M. L., J. Mounier, H. d'Hauteville, M. Coquis-Rondon, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1989. Identification of icsA, a plasmid locus of Shigella flexneri that governs intra and intercellular spread through interaction with F-actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3867-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullock, W. O., J. M. Fernandez, and J. M. Short. 1987. XL1-Blue: a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques 5:376-378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cersini A., A. M. Salvia, and M. L. Bernardini. 1998. Intracellular multiplication and virulence of Shigella flexneri auxotrophic mutants. Infect. Immun. 66:549-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coster, T. S., C. W. Hoge, L. L. Van De Verg, A. B. Hartman, E. V. Oaks, M. M. Venkatesan, D. Cohen, G. Robin, A. Fontaine-Thompson, P. J. Sansonetti, and T. L. Hale. 1999. Vaccination against shigellosis with attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain SC602. Infect. Immun. 67:3437-3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Silva, D. G., L. N. Mendis, N. Sheron, G. J. M. Alexander, D. C. A. Candy, H. Chart, and B. Rowe. 1993. Concentrations of interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor in serum and stools of children with Shigella dysenteriae I infection. Gut 34:194-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.d'Hauteville, H., S. Khan, D. J. Maskell, A. Kussak, A. Weintraub, J. Mathison, R. J. Ulevitch, N. Wuscher, C. Parsot, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2002. Two msbB genes encoding maximal acylation of lipid A are required for invasive Shigella flexneri to mediate inflammatory rupture and destruction of the intestinal epithelium. J. Immunol. 168:5240-5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dilworth, D. D., and J. R. McCarrey. 1992. Single step elimination of contaminating DNA prior to reverse transcriptase PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 1:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Formal, S. B., P. Gemsky, Jr., L. S. Baron, and E. H. LaBrec. 1971. A chromosomal locus which controls the ability of Shigella flexneri to evoke keratoconjunctivitis. Infect. Immun. 3:73-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman, A. B., C. Powell, C. L. Schultz, E. V. Oaks, and K. H. Eckels. 1991. Small animal model to measure efficacy and immunogenicity of Shigella vaccine strains. Infect. Immun. 59:4075-4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hueck, C. J. 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koprowski, H., II, M. M. Levine, R. J. Anderson, G. Losonsky, M. Pizza, and E. M. Barry. 2000. Attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain CVD 1204 expressing colonization factor antigen I and mutant heat-labile enterotoxin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:4884-4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotloff, K. L., F. R. Noriega, T. Samandari, M. B. Sztein, G. A. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, W. D. Picking, E. M. Barry, and M. M. Levine. 2000. Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1207, with specific deletions in virG, sen, set, and guaBA, is highly attenuated in humans. Infect. Immun. 68:1034-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotloff, K. L., J. P. Winickoff, B. Ivanoff, J. D. Clemens, D. L. Swerdlow, P. J. Sansonetti, G. K. Adak, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation. Bull. W. H. O. 77:651-656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindberg, A. A., A. Karnell, B. A. D. Stocker, S. Katakura, H. Sweiha, and F. Reinholt. 1988. Development of an auxotrophic oral live Shigella flexneri vaccine. Vaccine 6:146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallett, C. P., L. L. Van De Verg, H. H. Collins, and T. L. Hale. 1993. Evaluation of Shigella vaccine safety and efficacy in an intranasal challenged mouse model. Vaccine 11:190-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandic-Mulec, I., J. Weiss, and A. Zychlinsky. 1997. Shigella flexneri is trapped in polymorphonuclear leukocyte vacuoles and efficiently killed. Infect. Immun. 65:110-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Murray, J. S., J. P. Kasselman, and T. Schountz. 1995. High-density presentation of an immunodominant minimal peptide on B cells is MHC-linked to Th1-like immunity. Cell. Immunol. 166:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan, C., and M. U. Shiloh. 2000. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8841-8848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noriega, F. R., G. Losonsky, C. Lauderbaugh, F. M. Liao, J. Y. Wang, and M. M. Levine. 1996. Engineered ΔguaB-A ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1205: construction, safety, immunogenicity, and potential efficacy as a mucosal vaccine. Infect. Immun. 64:3055-3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noriega, F. R., G. Losonsky, J. Y. Wang, S. B. Formal, and M. M. Levine. 1996. Further characterization of ΔaroA ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2A strain CVD 1203 as a mucosal Shigella vaccine and as a live-vector vaccine for delivering antigens of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:23-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nygaard, Y. 1983. Utilization of preformed purine bases and nucleosides, p. 27-93. In A. Munch-Petersen (ed.), Metabolism of nucleotides, nucleosides, and nucleobases in microorganisms. Academic Press, Inc., London, United Kingdom.

- 30.Phalipon, A., M. Kaufmann, P. Michetti, J. M. Cavaillon, M. Huerre, P. J. Sansonetti, and J. P. Kraehenbuhl. 1995. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A antibody directed against serotype-specific epitope of Shigella flexneri lipopolysaccharide protects against murine experimental shigellosis. J. Exp. Med. 182:769-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philpott, D. J., S. Yamaoka, A. Israel, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2000. Invasive Shigella flexneri activates NF-κB through a lipopolysaccharide-dependent innate intracellular response and leads to IL-8 expression in epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 165:903-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Arondel, J. M. Cavaillon, and M. Huerre. 1995. Role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of experimental shigellosis. J. Clin. Investig. 96:884-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Arondel, A. Fontaine, H. d'Hauteville, and M. L. Bernardini. 1991. ompB (osmo-regulation) and icsA (cell to cell spread) mutants of Shigella flexneri: vaccine candidates and probes to study the pathogenesis of shigellosis. Vaccine 9:416-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Arondel, M. Huerre, A. Harada, and K. Matsushima. 1999. Interleukin-8 controls bacterial transepithelial translocation at the cost of epithelial destruction in experimental shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 67:1471-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sansonetti, P. J., A. Phalipon, J. Arondel, K. Thirumalai, S. Banerjee, S. Akira, K. Takeda, and A. Zychlinsky. 2000. Caspase-1 activation of IL-1beta and IL-18 are essential for Shigella flexneri-induced inflammation. Immunity 12:581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansonetti, P. J., A. Ryter, P. Clerc, A. T. Maurelli, and J. Mounier. 1986. Multiplication of Shigella flexneri within HeLa cells: lysis of the phagocytic vacuole and plasmid-mediated contact hemolysis. Infect. Immun. 51:461-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwan, W. R., and D. J. Kopecko. 1997. Uptake of pathogenic intracellular bacteria into human and murine macrophages downregulates the eukaryotic 26S protease complex ATPase gene. Infect. Immun. 65:4754-4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Verg, L. L., C. P. Mallett, H. H. Collins, T. Larsen, C. Hammack, and T. L. Hale. 1995. Antibody and cytokine responses in a mouse pulmonary model of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a infection. Infect. Immun. 63:1947-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma, N. K., and A. A. Lindberg. 1991. Construction of aromatic dependent Shigella flexneri 2a live vaccine candidate strains: deletion mutations in the aroA and the aroD genes. Vaccine 9:6-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshikawa, M., C. Sasakawa, N. Okada, M. Takasaka, M. Nakayama, Y. Yoshikawa, A. Kohno, H. Danbara, H. Nariuchi, H. Shimada, and M. Toriumi. 1995. Construction and evaluation of a virG thyA double mutant of Shigella flexneri 2a as candidate live-attenuated oral vaccine. Vaccine 13:1436-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zychlinsky, A., K. Thirumalai, J. Arondel, J. R. Cantey, A. O. Aliprantis, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1996. In vivo apoptosis in Shigella flexneri infections. Infect. Immun. 64:5357-5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zychlinsky, A., M. C. Prevost, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1992. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature 358:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]