Abstract

Myeloid differentiation protein 88 (MyD88) is a general adaptor for the signaling cascade through receptors of the Toll/IL-1R family. When infected with Leishmania major parasites, MyD88-deficient mice displayed a dramatically enhanced parasite burden in their tissues similar to that found in susceptible BALB/c mice. In contrast, MyD88 knockout mice did not develop ulcerating lesions despite a lack of interleukin-12 (IL-12) production and a predominant T helper 2 cell response. Blockade of IL-4 produced early (day 1) after infection restored a protective T helper 1 response in MyD88 knockout mice.

The outcome of many infections is determined by functionally distinct T helper (Th1 and Th2) cell populations secreting different patterns of cytokines. In murine cutaneous leishmaniasis, susceptible inbred mice such as BALB/c develop a dominant Th2 response, while in resistant mice, macrophage activation by the Th1 product gamma interferon (IFN-γ) is essential in controlling the intracellular protozoan parasite, Leishmania major (14, 17, 22). During the first days of infection, cells of the innate immune system are activated, not only enabling the host to develop specific immunity but also determining the type of immune response. For example, interleukin-12 (IL-12), mainly produced by dendritic cells, is essential for the development of a protective Th1 response in experimental leishmaniasis (20).

The recent discovery of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in cells of the innate immune system precipitated a major advance in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of both pathogen discrimination and inflammation (2, 3). TLRs constitute a family of at least 10 transmembrane proteins that differentially recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns through an extracellular domain and initiate inflammatory signaling pathways through an intracellular domain. TLRs bind MyD88, a protein that interacts with several other molecules in a signaling cascade that leads to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and production of cytokines such as IL-12. In addition, MyD88 is an essential adaptor protein in the signaling of the cytokines IL-1 and IL-18 (24).

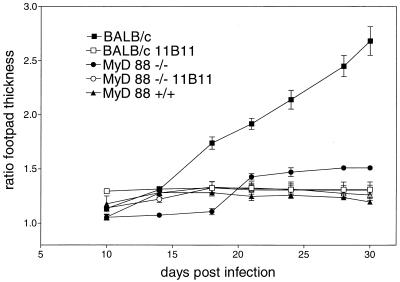

To evaluate the role of MyD88 in the initiation and development of an immune response against L. major, MyD88-deficient C57BL/6 mice (1) were infected subcutaneously in the right hind footpad with 2 × 106 L. major promastigotes (strain MOHM/IL/81/FEBNI) grown in vitro as described previously (7). For comparison, wild-type resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible BALB/c mice (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were infected simultaneously. The increase in lesion size was monitored twice weekly by measurement of footpad thickness with a metric caliper (Kroeplin Schnelltaster, Schlüchtern, Germany). While, as expected, BALB/c mice developed increasing ulcerating lesions at the site of infection (Fig. 1), only transient swelling was observed in C57BL/6 and MyD88-deficient C57BL/6 mice. Since it was shown previously, that neutralization of endogenous IL-4 by administration of monoclonal antibody 11B11 results in a robust and protective Th1 response in L. major-infected BALB/c mice (18), MyD88-deficent and BALB/c mice were treated with 1 mg of 11B11 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) intraperitoneally on day 1 after infection. Anti-IL-4-treated BALB/c mice were able to control the infection, while the course of lesion development was essentially not changed by the antibody treatment in MyD88-deficient mice (Fig. 1). In order to analyze the parasite load in the tissues of the infected mice, limiting-dilution tests with homogenates of the feet, the popliteal lesion-draining lymph nodes, and spleens were performed in accordance with previously published protocols (23). The parasite titers in BALB/c and MyD88-deficient mice were orders of magnitude higher than those in wild-type C57BL/6 control mice (Table 1). In vivo neutralization of IL-4 with monoclonal antibody 11B11 resulted in a drastic reduction in the number of Leishmania parasites in both BALB/c and MyD88-deficient mice to levels equivalent to those found in C57BL/6 mice.

FIG. 1.

Lesion development after infection with L. major. Female BALB/c, C57BL/6, and MyD88-deficient C57BL/6 mice were infected with 2 × 106 stationary-phase promastigotes of L. major in 50 μl of PBS subcutaneously in the right hind footpad. Mice received either 500 μl of PBS (controls) or 1 mg of anti-IL-4 antibody 11B11 in 500 μl of PBS intraperitoneally on day 1 after infection. The data shown represent the mean values and standard error of the mean of the footpad swelling of six mice in one of two similar experiments.

TABLE 1.

Parasite loads in tissues of L. major-infected micea

| Mouse strain (treatment) | Mean no. of viable parasites/organ ± SD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Foot | Lymph node | Spleen | |

| BALB/cb | 2.1 × 199 ± 0.7 × 109 | 1.3 × 108 ± 1.2 × 108 | 5.1 × 103 ± 3.5 × 103 |

| BALB/c (11B11)c | 5.0 × 104 ± 1.8 × 104 | 1.2 × 105 ± 9 × 104 | 0.013 × 103 ± 0.010 × 103 |

| MyD88−/−b | 1.1 × 109 ± 0.9 × 109 | 1.0 × 108 ± 0.9 × 108 | 1.9 × 103 ± 1.0 × 103 |

| MyD88−/− (11B11)c | 1.54 × 105 ± 1 × 105 | 1.4 × 106 ± 1.2 × 106 | 0.044 × 103 ± 0.03 × 103 |

| MyD88+/+b | 2.7 × 105 ± 1.4 × 105 | 0.9 × 106 ± 0.5 × 106 | 0.015 × 103 ± 0.013 × 103 |

Mice were infected with 2 × 106 promastigotes in the right hind footpad. After 35 days of infection, mice were sacrificed and numbers of viable L. major parasites were quantified by a limiting-dilution in vitro culture assay. Each value represents the mean of three animals.

Mice received 500 μl of PBS intraperitoneally on day 1 after infection.

Mice received 500 μl of PBS containing 1 mg of monoclonal antibody 11B11 intraperitoneally on day 1 after infection.

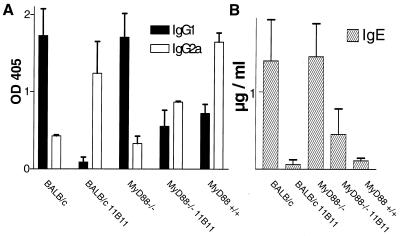

Protective immunity against L. major depends on the genetically determined ability to mount a Th1 response. Therefore, we analyzed the cellular and humoral immune response of MyD88-deficient and control mice. The L. major-specific serum immunoglobulin (Ig) isotypes and total IgE titers (15) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), since the proportional distribution of IgG2a, indicative of Th1 cells, and IgG1 and IgE, driven by Th2 cells, faithfully reflects the type of T helper cell response in vivo.

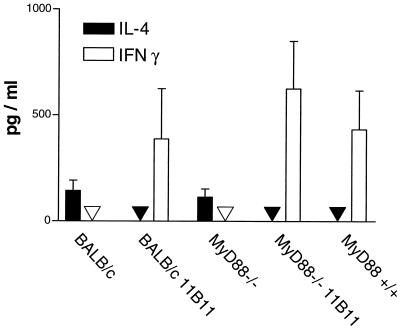

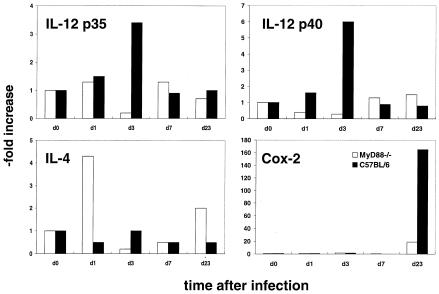

Like BALB/c mice, MyD88-deficient C57BL/6 mice had very high titers of parasite-specific IgG1 antibodies (Fig. 2A) and high concentrations of IgE (Fig. 2B) in their sera, indicating a dominant Th2 response. In contrast, in sera of C57BL/6 wild-type and 11B11-treated BALB/c and MyD88-deficient mice, predominantly Leishmania-specific IgG2a and only low levels of IgE were detected. These data were confirmed by cytokine expression analysis by commercially available ELISAs (BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany). While lymph node cells of the different infected mice showed similar rates of proliferation in response to L. major antigen preparations in vitro (data not shown), IFN-γ was only detected in the supernatants of antigen-stimulated cells obtained from C57BL/6 or anti-IL-4-treated BALB/c and MyD88-deficient mice (Fig. 3). In contrast, IL-4, the functionally most relevant Th2-derived cytokine, in this infection model, was present only in cell culture supernatants from stimulated lymph node cells from infected BALB/c and MyD88-deficient mice. In order to analyze the early cytokine mRNA expression in the lesion-draining lymph nodes, where the T helper cell differentiation takes place, reverse transcription, followed by quantitative real-time PCR, was performed. Total RNA from the tissues was isolated with an RNAqueous kit (Ambion Inc., Houston, Tex.). Reagents and enzymes for reverse transcription and real-time PCR were purchased from Invitrogen (Karslruhe, Germany), the reaction was performed, and the product was analyzed in a LightCycler (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). We used primers for IL-12p35 (5′, GGCCACCCTTGCCCTCCTA; 3′, GGGCAGGCAGCTCCCTCTT), IL-12p40 (5′, TCCAGCGCAAGAAAGAAAAGATG; 3′, AAAAGCCAACCAAGCAGAAGACAG), IL-4 (5′, TGACGGCACAGAGCTATTGATGG; 3′, AGCACCTTGGAAGCCCTACAGAC), and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) (5′, GGCCCTTCCTCCCGTAGCAG; 3′, AGACCAGGCACCAGACCAAAGACT) and two housekeeping genes (those for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase [10] and porphobilinogen deaminase[6]) for standardization for each sample. Enhanced expression of IL-12p35 and p40 was detected only in lymph nodes of wild-type C57BL/6 mice 3 days after infection (Fig. 4). Thus, our data show that MyD88-dependent signals are essential for the expression of IL-12p35 and p40 and subsequent development of a protective Th1 cell response in mice with a resistant genetic background. In contrast, very early expression of IL-4 (24 h after infection), shown previously to be decisive for the development of Leishmania-specific Th2 cells (13), was detected only in lymph nodes of MyD88-deficient mice (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, IL-4 has recently been shown also to possess Th1-cell-driving potential in mice infected with L. major (4). However, this function is most likely dependent on TLR-mediated cosignals, as shown for enhancement of IL-12 production by dendritic cells in the presence of IL-4 (11). Since TLR-mediated signals, which are able to initiate robust Th1 responses in L. major-infected BALB/c mice (27), are severely comprised in MyD88-deficient mice, IL-4 presumably lacks its Th1-inducing capacity in this setting.

FIG. 2.

Humoral immune response in L. major-infected mice. The titers of L. major-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies (A) and concentrations of total IgE (B) were determined on day 35 after infection. The mean and standard deviation are shown.

FIG. 3.

Cytokine secretion by cells from lesion-draining lymph nodes on day 35 after infection. Cells (2 × 106/ml) were stimulated in vitro for 48 h. Concentrations of IL-4 and IFN-γ were determined by ELISA. The mean and standard deviation of three mice per group are shown.

FIG. 4.

Expression of cytokine and COX-2 mRNAs in lesion-draining lymph nodes during the course of infection. Total RNA was isolated from the lymph nodes of two mice per group at each time point indicated. After reverse transcription, the concentrations of IL-12p35, p40, IL-4, and COX-2 cDNAs were determined by real-time PCR and normalized for two housekeeping genes. The data shown are the means of four determinations.

It remains unclear which MyD88-dependent receptors might be involved. However, experiments with TLR2/4 double-deficient mice (kindly provided by C. Kirschning, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany), which displayed a normal protective Th1 response against L. major (our unpublished observations), argue against these two TLRs as essential receptors in this parasitic infection. Since IL-18, which exerts its signals via MyD88, has been previously shown not to be essential for the development of Th1 cells in L. major-infected mice (16), the findings suggest that lack of IL-12 production is the main reason for the absence of Th1 development in MyD88-deficient mice. We have initiated experiments to further address this point. Consistent with this idea, it has been demonstrated that T. gondii-induced IL-12 production by dendritic cells is dramatically reduced in mice lacking MyD88 (19). High susceptibility of MyD88-deficient mice has been previously reported for experimental models of acute (5, 25) and chronic (19) infections. Only in the case of a model antigen has it been recently demonstrated that MyD88 is essential for the development of Th1 cells (21). We have extended this finding by showing for the first time that MyD88 is also essential for the development of protective Th1 cells in a chronic experimental infection. Furthermore, we have shown for the first time that neutralization of IL-4 in vivo is sufficient to enable Th1 development even in the absence of MyD88. Surprisingly, and of special interest, despite their Th2 response and the high parasite numbers in their tissues, MyD88-deficient C57BL/6 mice do not develop chronically ulcerating lesions like BALB/c mice after infection with L. major strain MOHM/IL/81/FEBNI. Thus, MyD88-dependent mechanisms appear to be essential for the development of this type of chronic inflammation. It has been shown recently that MyD88 is essential for enhanced expression of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1α by L. major-infected macrophages in vitro (9). A second candidate involved in inflammatory processes and immunoregulation is the inducible cyclooxygenase isoform COX-2 (for a review, see reference 8). Prostaglandins, especially prostaglandin E2, produced by this enzyme favor influx of inflammatory cells and tissue destruction by induction of matrix metalloproteinases (8). It is of interest that COX-2 is markedly upregulated as late as 23 days after infection in tissues of control mice while its expression was significantly lower in mice lacking MyD88 (Fig. 4). On the basis of previous publications showing (i) that TNF-α-deficient C57BL/6 mice do not develop chronic ulcerating lesions although they are unable to control parasite replication (26) and (ii) that TNF-α production is controlled by MyD88-mediated signaling (12), this cytokine is a possible additional key factor in ulcer formation. In sum, analysis of L. major-infected MyD88-deficient mice clearly demonstrated the essential role of this molecule for Th1 cell development in a chronic infection. Future experiments will address MyD88-dependent processes that cause chronically tissue-destroying inflammatory processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Akira, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan, and C. Kirschning, Munich, Germany, for generously supplying MyD88-deficient and TLR2/4 double-deficient mice, respectively, and M. Schnare for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by IZKF Erlangen grant A2 and the DFG (SFB 466, B10).

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, O., T. Kawai, K. Takeda, M. Matsumoto, H. Tsutsui, M. Sakagami, K. Nakanishi, and S. Akira. 1998. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity 9:143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira, S., K. Takeda, and T. Kaisho. 2001. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2:675-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton, G. M., and R. Medzhitov. 2002. Toll-like receptors and their ligands. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 270:81-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biedermann, T., S. Zimmermann, H. Himmelrich, A. Gumy, O. Egeter, A. K. Sakrauski, I. Seegmuller, H. Voigt, P. Launois, A. D. Levine, H. Wagner, K. Heeg, J. A. Louis, and M. Rocken. 2001. IL-4 instructs TH1 responses and resistance to Leishmania major in susceptible BALB/c mice. Nat. Immunol. 2:1054-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelson, B. T., and E. R. Unanue. 2002. MyD88-dependent but Toll-like receptor 2-independent innate immunity to Listeria: no role for either in macrophage listericidal activity. J. Immunol. 169:3869-3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink, L., W. Seeger, L. Ermert, J. Hanze, U. Stahl, F. Grimminger, W. Kummer, and R. M. Bohle. 1998. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR after laser-assisted cell picking. Nat. Med. 4:1329-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gessner, A., K. Schroppel, A. Will, K. H. Enssle, L. Lauffer, and M. Rollinghoff. 1994. Recombinant soluble interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor acts as an antagonist of IL-4 in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 62:4112-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris, S. G., J. Padilla, L. Koumas, D. Ray, and R. P. Phipps. 2002. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends Immunol. 23:144-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawn, T. R., A. Ozinsky, D. M. Underhill, F. S. Buckner, S. Akira, and A. Aderem. 2002. Leishmania major activates IL-1α expression in macrophages through a MyD88-dependent pathway. Microbes Infect. 4:763-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzel, F. P., R. M. Rerko, and A. M. Hujer. 1998. Underproduction of interleukin-12 in susceptible mice during progressive leishmaniasis is due to decreased CD40 activity. Cell Immunol. 184:129-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochrein, H., M. O'Keeffe, T. Luft, S. Vandenabeele, R. J. Grumont, E. Maraskovsky, and K. Shortman. 2000. Interleukin (IL)-4 is a major regulatory cytokine governing bioactive IL-12 production by mouse and human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 192:823-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai, T., O. Adachi, T. Ogawa, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 1999. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity 11:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Launois, P., I. Maillard, S. Pingel, K. G. Swihart, I. Xenarios, H. Acha-Orbea, H. Diggelmann, R. M. Locksley, H. R. MacDonald, and J. A. Louis. 1997. IL-4 rapidly produced by Vβ4Vα8 CD4+ T cells instructs Th2 development and susceptibility to Leishmania major in BALB/c mice. Immunity 6:541-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis, J., A. Gumy, H. Voigt, M. Rocken, and P. Launois. 2002. Experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis: a powerful model to study in vivo the mechanisms underlying genetic differences in Th subset differentiation. Eur. J. Dermatol. 12:316-318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohrs, M., B. Ledermann, G. Kohler, A. Dorfmuller, A. Gessner, and F. Brombacher. 1999. Differences between IL-4- and IL-4 receptor alpha-deficient mice in chronic leishmaniasis reveal a protective role for IL-13 receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 162:7302-7308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monteforte, G. M., K. Takeda, M. Rodriguez-Sosa, S. Akira, J. R. David, and A. R. Satoskar. 2000. Genetically resistant mice lacking IL-18 gene develop Th1 response and control cutaneous Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 164:5890-5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiner, S. L., and R. M. Locksley. 1995. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:151-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadick, M. D., F. P. Heinzel, B. J. Holaday, R. T. Pu, R. S. Dawkins, and R. M. Locksley. 1990. Cure of murine leishmaniasis with anti-interleukin 4 monoclonal antibody. Evidence for a T cell-dependent, interferon gamma-independent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 171:115-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scanga, C. A., J. Aliberti, D. Jankovic, F. Tilloy, S. Bennouna, E. Y. Denkers, R. Medzhitov, and A. Sher. 2002. Cutting edge: MyD88 is required for resistance to Toxoplasma gondii infection and regulates parasite-induced IL-12 production by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 168:5997-6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scharton-Kersten, T., L. C. Afonso, M. Wysocka, G. Trinchieri, and P. Scott. 1995. IL-12 is required for natural killer cell activation and subsequent T helper 1 cell development in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 154:5320-5330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnare, M., G. M. Barton, A. C. Holt, K. Takeda, S. Akira, and R. Medzhitov. 2001. Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2:947-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solbach, W., and T. Laskay. 2000. The host response to Leishmania infection. Adv. Immunol. 74:275-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stenger, S., H. Thuring, M. Rollinghoff, and C. Bogdan. 1994. Tissue expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase is closely associated with resistance to Leishmania major. J. Exp. Med. 180:783-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeuchi, O., and S. Akira. 2002. MyD88 as a bottle neck in Toll/IL-1 signaling. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 270:155-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi, O., K. Hoshino, and S. Akira. 2000. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 165:5392-5396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilhelm, P., U. Ritter, S. Labbow, N. Donhauser, M. Rollinghoff, C. Bogdan, and H. Korner. 2001. Rapidly fatal leishmaniasis in resistant C57BL/6 mice lacking TNF. J. Immunol. 166:4012-4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann, S., O. Egeter, S. Hausmann, G. B. Lipford, M. Rocken, H. Wagner, and K. Heeg. 1998. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides trigger protective and curative Th1 responses in lethal murine leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 160:3627-3630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]