Abstract

Background:

Recently, we noted increasing number of cases of Kaposi's varicelliform eruption (KVE) among dermatology in-patients who were being treated for various dermatoses, some of which have not been reported earlier to be associated with KVE, and hence, this report.

Aims:

This study was designed to identify various dermatoses in which KVE occurred, to study the clinical features, course and response to specific antiviral treatment, to establish the risk factors, and course of the primary dermatoses during the episode of KVE.

Materials and Methods:

We analyzed our data of dermatology in-patients in a tertiary care centre in South India from April 2008 to November 2009 (20 months). The data were tabulated and analyzed.

Results:

Twenty cases (12 female and 8 male patients) of KVE were seen. The mean age of the patients was 46.4 years. There were seven cases of erythroderma, four of pemphigus vulgaris, three of toxic epidermal necrolysis, two of airborne contact dermatitis (ABCD), one each of lichenoid drug rash, and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Underlying dermatoses for erythroderma were: ABCD (3), psoriasis (3), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (1). Possible source of infection could be identified in five cases: exogenous sources in four cases and endogenous source in one case. The mean incubation period for cases with known source was 5 days (range, 2–9 days). Eighteen patients responded favorably to acyclovir. None of our patients had recurrent KVE during the study period.

Conclusion:

KVE may complicate any dermatosis where the integrity of the skin is compromised. Diagnosis and early treatment are important and possible in most cases if suspected.

Keywords: Dermatoses, India, Kaposi's varicelliform eruption, tertiary care centre

Introduction

Kaposi's varicelliform eruption (KVE), also known as eczema herpeticum, refers to a widespread cutaneous infection with a virus that normally causes localized or mild vesicular eruptions, occurring in a patient with pre-existing skin disease.[1] Most cases are due to herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections, but coxsackie A16 and vaccinia may also be responsible in a minority of patients.[1] Majority of cases are seen in atopic dermatitis. However, many other disorders such as dyskeratosis follicularis, pemphigus foliaceus, mycosis fungoides, Sιzary syndrome, ichthyosis vulgaris, and Hailey-Hailey disease may be secondarily affected by KVE.[2] Recently, we have noted increasing number of cases of KVE among dermatology in-patients who were being treated for various dermatoses, some of which have not been reported earlier to be associated with KVE, and hence, this report.

Methods

We analyzed our data of dermatology in-patients in a tertiary care centre in South India from April 2008 to November 2009 (20 months) to identify various dermatoses in which KVE was occurring. An attempt was made to study the clinical features, course and response to specific antiviral treatment, establish the risk factors, and course of the primary dermatoses during the episode of KVE. The data were tabulated and analyzed.

Results

Age and gender

Twenty cases of KVE were seen over a period of 20 months. The sex ratio was 1.5:1 (12 female and 8 male patients). The mean age of the patients was 46.4 years (range, 12–75 years). The mean age of the male patients was 60.8 years, and that of the female patients was 36.7 years.

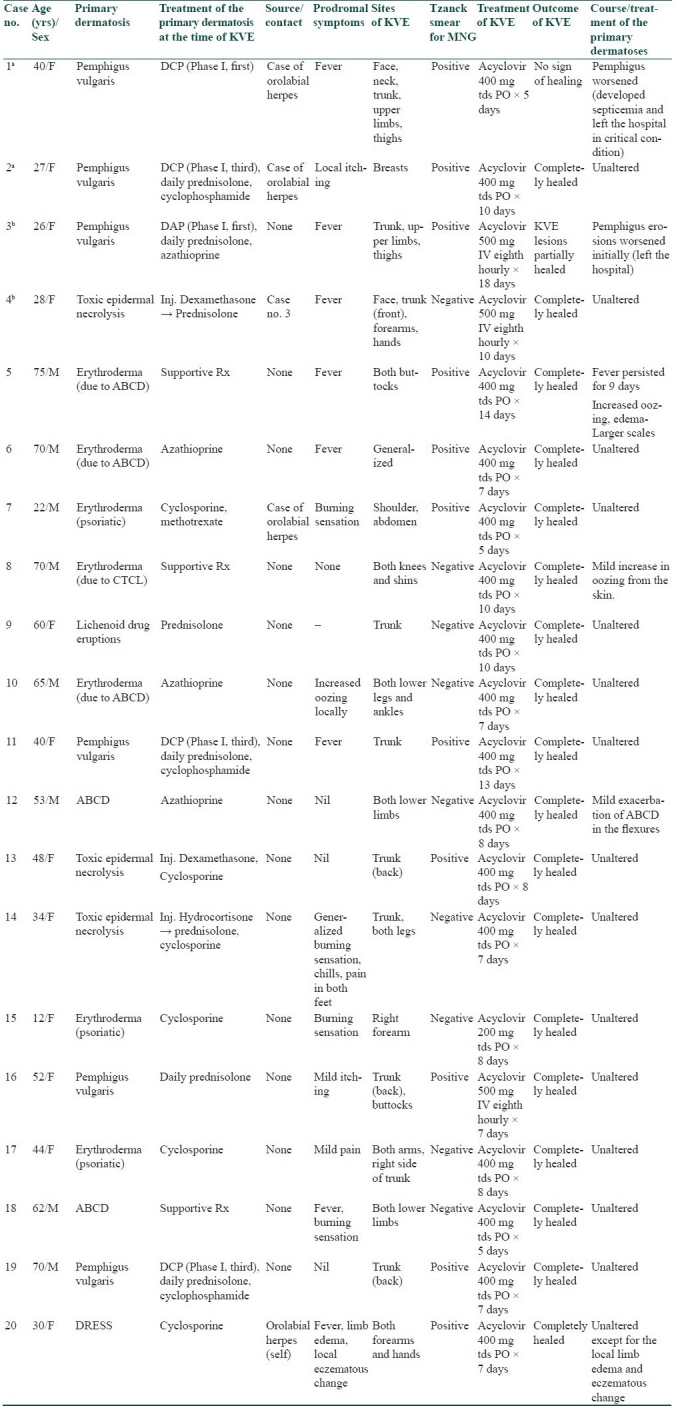

The clinical profile of the patients is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Profile of cases with Kaposi's varicelliform eruption

Primary dermatoses

There were seven cases of erythroderma, four of pemphigus vulgaris [Figure 1], three of toxic epidermal necrolysis, two of airborne contact dermatitis (ABCD), one each of lichenoid drug rash, and drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Underlying dermatoses for erythroderma were – ABCD (3), psoriasis (3), and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) (1).

Figure 1.

Typical umbilicated vesicles and erosions of KVE in pemphigus vulgaris

Source of infection and prodromal symptoms

Possible source of infection could be identified in five cases: exogenous sources in four cases (orolabial herpes simplex: three cases and another KVE case: 1 case), and endogenous source in one case (orolabial herpes simplex). The mean incubation period for cases with known source was 5 days (range, 2–9 days). Fever, starting 0–5 days before the onset of KVE lesions, was seen as a prodromal symptom in eight patients. Other prodromal symptoms were local itching (two cases), burning sensation (four cases), increased oozing from the local site (one case), chills, pain, local edema, and eczematous change.

Clinical presentation

Monomorphic vesicles as the initial lesions (lesions of recognition) were recognized in eight patients and pustules in one. In the remaining 11, initial lesions were erosions. With regard to the morphology of the established lesions, four cases had superficial erosions (Case no. 6, 7, 9, and 19 in Table 1). Remaining all cases had deep erosions. The established erosions remained discrete in 13 cases, and showed coalescence to form polycyclic/serpiginous lesions in seven cases. Fifteen patients had limited involvement (localized to three or less than three anatomical regions); the remaining five patients had extensive involvement (more than three anatomical regions). Trunk was involved in 11 cases, lower limbs in 7, upper limbs in 6, face in 2, buttocks in 2, neck in 1, breasts in 1, and generalized involvement in 1.

Investigations and treatment

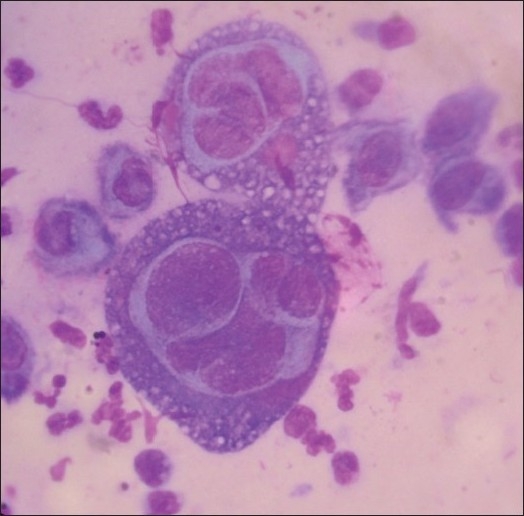

Tzanck smear examination showed multinucleate giant cells (MNG) in 11 cases [Figure 2]. Remaining nine cases did not show MNG, though morphology of lesions was suggestive of KVE. Acyclovir was given in all the patients: 17 patients received oral acyclovir for a mean duration of 8.2 days and three patients received IV acyclovir (because of extensive involvement or unfavorable clinical circumstance) for a mean duration of 11.6 days.

Figure 2.

Tzanck smear demonstrating multinucleated giant cells (Giemsa stain, ×1000)

Outcome

The KVE lesions healed completely in 18 patients. Of these 18 patients, the course and treatment of the primary dermatoses were unaltered in 14 patients during the episode of KVE. Two patients of erythroderma (both receiving only supportive treatment for erythroderma), and one patient of ABCD had mild-to-moderate exacerbation of the lesions during KVE. One patient of DRESS had edema and eczematous changes at the site of KVE.

Two patients left the hospital in critical conditions against medical advice: one showed partial healing of KVE, whereas the other showed no sign of healing of KVE lesions.

None of our patients had recurrent KVE during the study period.

Discussion

Austrian dermatologist Moriz Kaposi gave the first description of what is known today as KVE or eczema herpeticum. Some authors, however, distinguish between these two terms: eczema herpeticum refers to a disseminated HSV infection as a complication of an eczematous skin disease, whereas KVE is used for any disseminated cutaneous infection with the HSV type 1 or 2.[2]

KVE is generally believed to be a disease of childhood.[3] However, in our study, KVE occurred in the older age group, especially in the male patients. Source of KVE may be herpes simplex infections in family members or other close contacts.[1,3] However, in one study of 75 cases, 20% followed ordinary recurrent herpes labialis, so that eczema herpeticum may result from endogenous recurrent infection.[3] In our study, a possible source could be identified in five cases only, whereas no clear-cut source of infection could be identified in 15 cases.

Constitutional symptoms such as fever may be mild to very high. In Bork and Brauninger study,[3] only 16 out of 75 patients had high fever whereas 35 patients had no fever. In our study, eight patients had fever during the episode of KVE. We feel that unexplained fever in a patient with compromised skin could be a harbinger of KVE.

KVE presents as disseminated, distinctly monomorphic eruption of dome-shaped vesicles, which may transform into pustules or erosions. Atypical variants with characteristic, disseminated lesions in tense erythematous plaques may also occur.[2] In our study, 11 patients did not show the initial vesicles or pustules. Established lesions were erosions in all these 11 patients. Some patients (seven cases) showed polycyclic/serpiginous erosions caused by coalescence of lesions. Basically, exacerbation of previously existing dermatosis in case under treatment with associated fever made us suspect KVE. The finding of new evolving monomorphic lesions with typical umbilication in some cases and/or extension or development of erosions helped us to clinically clinch the diagnosis. It is worthwhile to carefully look for the lesions of KVE in suspected cases as in some patients the erosions may be hidden beneath the crusts of the primary disease (like Case no. 1 in Table 1) or the morphology of the erosions may be altered by secondary bacterial infections. The head, neck, and the upper part of the body are most frequently affected.[2] However, in our study, trunk was the commonest site of involvement followed by lower and upper limbs.

Apart from atopic dermatitis,[2,3] KVE has also been reported in dyskeratosis follicularis,[2,4] pemphigus foliaceus,[2,5,6] mycosis fungoides,[4,7] CTCL,[8] Sιzary syndrome,[2] ichthyosis vulgaris,[2,4] Hailey-Hailey disease,[2,9] psoriasis (psoriasis herpeticum),[4] and in patients with burns.[2] KVE has also been reported in congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, neurodermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome,[10] scabies,[5] bullous pemphigoid,[5] irritant dermatitis,[11] pemphigus vulgaris,[5,6] toxic epidermal necrolysis,[6] sunburn, after dermatologic therapeutics including skin autografting, topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis, after dermabrasion, after vaccination with BCG and vaccinia, and lupus vulgaris.[4,5,8,11,12] KVE has also been reported in Grover's disease,[13] rosacea,[14] and parthenium dermatitis.[15] In our study, KVE occurred in patients with erythroderma (secondary to ABCD, psoriasis, and CTCL), pemphigus vulgaris, toxic epidermal necrolysis, ABCD, lichenoid drug rash, and DRESS.

The severity of the primary dermatoses may have a bearing on the occurrence of KVE. KVE may be worse in patients with severe skin disorder, especially erythrodermic, atopic eczema but frequently occurs in mild or quiescent cases.[1] In our study, 18 patients had extensive primary dermatoses.

The role of topical corticosteroids in the causation of KVE is not clear.[1] However, systemic corticosteroids may be associated with occurrence of KVE.[3] Whether heavy steroid use predisposes to herpetic infection or simply reflects the severity of the eczema is unknown.[1] Other topical and systemic immunosuppression has also been associated with eczema herpeticum, namely topical tacrolimus.[1] In our study, 17 out of 20 patients were on some form of immunosuppressives (systemic corticosteroids, cyclophophamide, azathioprine, and cyclosporine) which were required to control the severity of the primary dermatosis.

The disease may be localized or generalized, with rare progression to potentially fatal systemic infection.[1] Mortality may be associated with KVE as a result of systemic viremia leading to a multiple organ involvement.[2] In our study, no mortality was recorded, but two patients left the hospital in critical condition (one of them was in septicemia). Recurrent episodes may occur.[1] Recurrences of KVE were noted in five of 10 and eight of 75 cases in one study.[3] No recurrences were noted in our study.

Antiviral therapy with acyclovir is the treatment of choice, usually combined with a systemic antibiotic to control heavy bacterial colonization.[2] In the series by Bork and Brauninger[3] as well as other reports[4–8,10,16–18] support the view that acyclovir brings about resolution of KVE lesions over several days in most patients. In our study, 18 out of 20 patients showed complete healing of KVE lesions. Among those responding to the treatment, the course of the primary dermatoses remained unaltered in most patients (14 out of 18) and only a mild-to-moderate exacerbation of the primary dermatosis in the remaining four patients. In those who were receiving immunosuppressives, we did not alter the dose of those agents except that dexamethasone/cyclophosphamide pulse was deferred until the KVE lesions completely subsided.

The drawback of our study was that we were not able to isolate the virus causing KVE in our patients due to logistic constraints. However, response to appropriate doses of acyclovir along with unaltered treatment for the primary dermatoses points toward HSV etiology. Hence, initiating acyclovir therapy empirically may be deemed appropriate in a setup where facilities for viral isolation or detection are not available, but Tzanck smear shows MNG. Acyclovir is to be continued until all the KVE erosions heal. If otherwise not indicated, antibiotics are not routinely required.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Sterling JC. Viral infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004. pp. 25.35–25.37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wollenberg A, Zoch C, Wetzel S, Plewig G, Przybilla B. Predisposing factors and clinical features of eczema herpeticum: a retrospective analysis of 100 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:198–205. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bork K, Bräuninger W. Increasing incidence of eczema herpeticum: analysis of seventy-five cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:1024–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santmyire-Rosenberger BR, Nigra TP. Psoriasis herpeticum: three cases of Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:52–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palleschi GM, Falcos D, Giacomelli A, Caproni M. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in pemphigus foliaceus. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:809–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao GR, Chalam KV, Prasad GP, Sarnathan M, Kumar H. Mini outbreak of Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in skin ward: a study of five cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:33–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.30649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi S, Yamada Y, Dekio S, Jidoi J. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in a patient with mycosis fungoides. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1997;22:41–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1997.1920609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masessa JM, Grossman ME, Knobler EH, Bank DE. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:133–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flint ID, Spencer DM, Wilkin JK. Eczema herpeticum in association with familial benign chronic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:257–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrio J, Lázaro P, Barrio JL. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:510–1. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morganroth GS, Glick SA, Perez MI, Castiglione FM Jr, Bolognia JL. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption complicating irritant contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:1030–1. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lübbe J, Sanchez-Politta S, Tschanz C, Saurat JH. Adults with atopic dermatitis and herpes simplex and topical therapy with tacrolimus: what kind of prevention? Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:670–1. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosann MK, Fogelman JP, Stern RL. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in a patient with Grover's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:914–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kucukyilmaz I, Alpsoy E, Yazar S. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in association with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhakar AC, Dogra S, Handa S. Eczema herpeticum complicating Parthenium dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2005;16:78–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimata H. Rapidly increasing incidence of Kaposi's varicelliform eruption in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:260–1. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shenoy MM, Suchitra U. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:65. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.30664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimata H. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption associated with the use of tacrolimus ointment in two neonates. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:262–3. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]