Abstract

Background:

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), are the acute emergencies in dermatology practice. Prompt diagnosis and management may reduce the morbidity and mortality in SJS/TEN patients. Early identification of the offending drug is necessary for early withdrawal and to prevent the recurrences of such a devastating illness.

Aims

To study the demography, offending agents, clinical and laboratory features, treatment, complications, morbidity and mortality of SJS/TEN in our hospital.

Materials and Methods:

In this retrospective study, we reviewed the medical records of SJS, TEN, SJS/TEN overlap of inpatients over a period of 10 years

Results:

Maximum number of SJS/TEN cases were in the age group of 11-30 years. Males predominated in the SJS group with a ratio of 1.63:1, whereas females predominated the TEN group with a ratio of 1:2.57.Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were the commonest group of drugs among the SJS group in 5/21 patients (23.8%). Antimicrobials were the commonest group of drugs causing TEN in 11/25 patients (44%). Mucosal lesions preceded the onset of skin lesions in nearly 50%. Our study had one patient each of SJS/TEN due to amlodipine and Phyllanthus amarus, an Indian herb. The most common morbidity noted in our study was due to ocular sequelae and sepsis leading to acute renal failure respectively. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption was found in three of our patients.

Conclusion:

Antimicrobials and NSAIDS are the common offending agents of SJS/TEN in our study.

Keywords: Stevens-Johnson syndrome, retrospective analysis, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Introduction

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), SJS/TEN overlap, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), are variants of acute, rapidly progressive mucocutaneous reactions which differ only in their body surface area (BSA) involvement.[1] Drugs, infections, vaccines, radiological contrasts, vaginal suppositories,[1] acrylonitrates, graft versus host reaction,[1] and lupus erythematosus[1] in predisposed individuals result in immunologically mediated keratinocyte apoptosis, and hence, extensive necrosis and detachment of epidermis with significant morbidity and mortality. Several studies and case reports on SJS/TEN have been done in India as well as abroad since the description of SJS case by Stevens and Johnson in 1922[1] and TEN case by Lyell's in 1956.[1] A hospital-based retrospective study was done to study the demography, offending agents, clinical and laboratory features, treatment, complications, morbidity and mortality in SJS/TEN in our hospital.

Materials and Methods

Medical records of all inpatients, admitted with a diagnosis of SJS, TEN, and SJS/TEN overlap over a period of 10 years from June 98 to July 08, in the Department of Dermatology, at our institute were reviewed. Of the total 56 medical records, 46 with complete data were selected. Bastugi's criteria[2] formed the basis for classifying these severe mucocutaneous reactions into SJS, TEN and SJS/TEN overlap. Parameters like age, sex, co-morbid conditions, etiology, clinical features, past history of drug reactions, period of hospital stay, investigations, treatment modalities, course and outcome of these 46 patients were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Age and gender

The number of patients with SJS and TEN was 21 each and with SJS/TEN overlap was four. Four patients in overlap group were included in TEN group. Maximum number of SJS cases was in the age group of 11–20 years and the maximum number of TEN cases was in the 20–30 years age group. Males predominated the SJS group with a ratio of 1.63:1, whereas females predominated in the TEN group with a ratio of 1:2.57. The youngest patient was a 3-year-old child and the oldest was a 78-year-old male.

Etiology

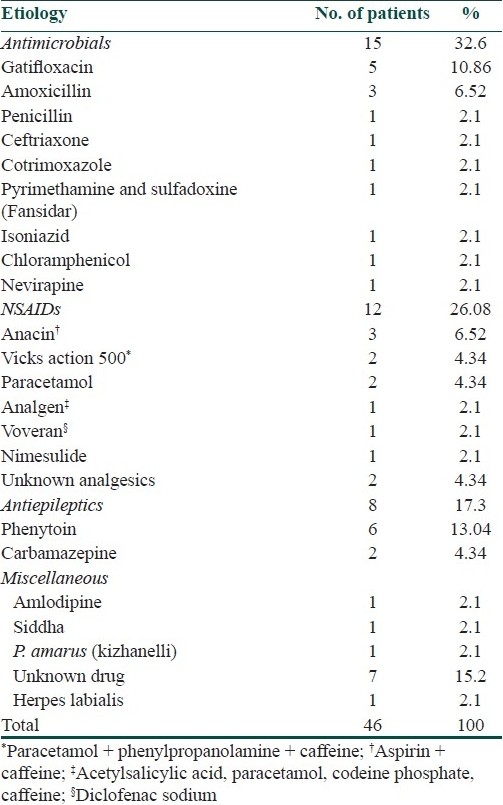

Drug as an etiology was established in almost all the cases except in one case of SJS which was due to herpes labialis. The implicated drug was identified in only 36 cases. The major group of drugs causing SJS/TEN in our study was antimicrobials 15/46 (32.6%), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 12/46 (26.08%) and antiepileptic drugs 8/46 (17.3%). Besides this, there were two cases of TEN due to paracetamol and one case each due to nevirapine, isoniazid, fansidar (pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine), amlodipine, siddha medication, and Phyllanthus amarus (kizhanelli), a common medicinal plant used for hepatitis B in south India.

Considering the mucocutaneous reactions individually, NSAIDs were the commonest group of drugs among the SJS group in 5/21 patients (23.8%). Antimicrobials like fluroquinolones, penicillin group of drugs were the commonest group causing TEN in 11/25 patients (44%). At least more than eight patients (17.3%) developed SJS/TEN following consumption of over-the-counter medications for analgesia. Anacin, analgen (contains acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol, codeine phosphate, and caffeine) and Vicks action 500 (contains paracetamol, phenylpropanolamine, and caffeine) were the common over-the-counter medications. The drugs which were implicated in causing SJS/TEN in our patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agents involved in SJS/TEN

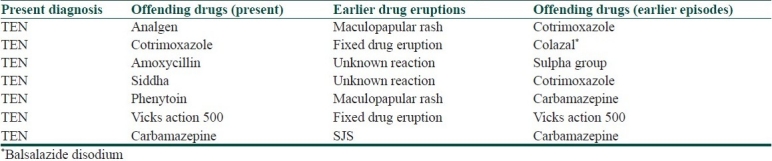

Past history of drug reaction was present in seven cases of TEN. Nature of past and present reaction in patients with previous history of drug eruption is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nature of past and present reaction in patients with previous history of drug eruption

The co-morbid conditions for which our patients were taking these offending drugs were seizures (8), diabetes mellitus (5), hypertension (3), HIV (2), pulmonary tuberculosis (2), enteric fever (2), one case each of syphilis, non Hodgkin's lymphoma, hypothyroidism, astrocytoma, hemiparesis, carcinoma cervix, carcinoma breast, lichen planus and hepatitis B.

Reaction time

The mean duration between the drug intake and the onset of reaction was 6 days. The reaction time was less than a week in most of our patients [29/46 (63%)].

Clinical features

Fever, sore throat, myalgia and burning sensation were the major prodromal symptoms experienced by our patients. Anaphylaxis was observed in one of the SJS patient. SJS patients had either blanchable or non blanchable purpuric macules, typical and atypical targets lesions, vesicles, bullae and erosions over erythematous and urticated plaques, involving <10% of BSA. TEN patients presented with sudden onset of large sheets of epidermal necrosis along with severe constitutional features. Nikolsky's sign and skin tenderness were present in all TEN patients. Four TEN patients had crusted erosions over the scalp.

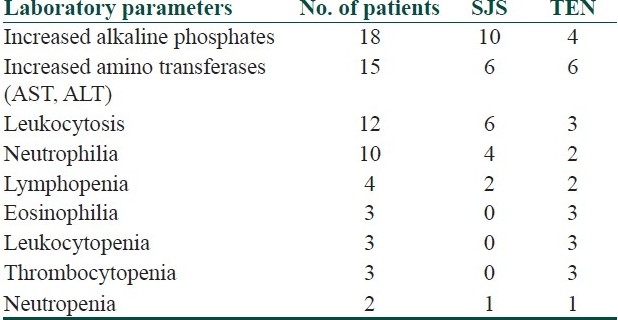

Mucosal lesions preceded the onset of skin lesions in nearly 50% of our patients. Also, 87% of SJS and 88% of TEN had oral mucosal involvement. All three (oral, conjunctiva, genital) mucosa were involved in 20/46 (43.47%) patients. Oral mucosal involvement was the most common followed by the conjunctiva. Other mucosal involvement noted was that of pharyngeal and anal. Abnormal laboratory parameters noted in our cases are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Laboratory parameters

Most of our patients had neutrophilic leukocytosis and raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Eosinophilia was seen in only three patients. Three TEN patients had thrombocytopenia and leukopenia. Neutropenia was noticed in two patients. Elevated liver enzymes were noticed in 18 of our patients.

Systemic complications observed in our study were acute renal failure (4), septicemia (4, all died, none on dexamethasone pulse therapy), metabolic encephalopathy (1), lower respiratory infection (2), congestive cardiac failure (2), pulmonary edema (2), hyperkalemia, intracranial bleed, aspirational pneumonia, psychosis, lung abscess, wound infection commonly due to Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), followed by Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, Klebsiella. One case of herpes labialis and three cases of Kaposi's varicelliform eruption developed during the regression of the reaction. Post inflammatory pigmentation was noted in almost all cases. Other mucocutaneous complications that we noticed were oral candidiasis, gastritis in the form of hematemesis, phimosis parotitis, tonsillitis, and epiglottitis. The number of patients with ocular morbidity in our study was 23/46 (50%) comprising of symblepharon (23), corneal scarring, bacterial, viral conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and corneal xerosis.

Treatment

Except for seven patients, all other patients received definitive therapy in the form of dexamethasone (17), prednisolone (11), methyl prednisolone pulse (2), dexamethasone pulse (2) and cyclosporine (7). Pulse therapy was given along with intravenous broad spectrum antibiotics. Overall, healing was noticed at 2–15 days after the onset of treatment. For dexamethasone pulse therapy, the onset of healing was on the third day of pulse, and for methylprednisolone pulse therapy, it was on the second day of pulse. The period of hospitalization ranged from 5 to 30 days, and it was lowest for methylprednisolone pulse therapy. Apart from hemoptysis due to gastritis in one patient, we did not record any other complications including sepsis and septicemia, in patients on dexamethasone pulse therapy.

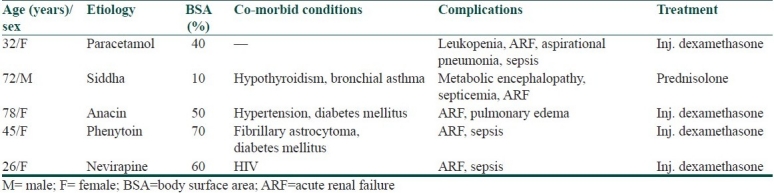

The SCORTEN score for 21 TEN cases ranged from 0 to 5. Five of the SJS/TEN cases died giving a mortality rate of 10.86% (5/46). The cause for death in all our patients was sepsis leading to acute renal failure [Table 4].

Table 4.

The profile of patients who died of complications

This study was based on inpatient records; we did not record long-term sequelae in such patients.

Discussion

Acute disseminated epidermal necrosis (ADEN 1, 2, 3) is the recently proposed terminology by Ruiz-Maldonado for SJS, overlap, and TEN, respectively. SJS/TEN are more common among individuals with lowered ability to detoxify reactive metabolites or alteration in detoxifying enzymes due to genetic basis (HLA-B 12, HLA-A29, HLA-DR7),[3] or functional basis (enzyme dysfunction due to AIDS or other disease).[1] Drug and/or their reactive metabolites behave as haptens and render the keratinocyte antigenic by binding to them. This elicits immune reactions resulting in extensive keratinocyte apoptosis which is mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced caspase cascade through perforin-granzyme route, FAS (CD95)-FAS ligand pathway, or nitric oxide synthase route in susceptible individuals.[1]

We had an equal number of SJS and TEN patients (21 patients each), as the study was done in a tertiary care hospital. In contrast to the general concept that adverse events are more common in extremes of age due to impaired hepatic enzymes and renal functions, our study had young patients in the first and second decades in both groups. This is similar to other studies done in India where Sharma et al.[4] noticed a mean age of 22.3 ± 15.4 years and Devi et al.[5] observed 68% of patients in the 20-50 years age group. A study done in West Germany[6] showed a higher age group for TEN (63%) and a lower age group for SJS (25%). Yamane et al.[7] from Japan noticed a mean age of 45.7 years and Roujeau et al.[8] from France observed a mean age of 46.8 years. Strikingly, there was a difference in the sex ratio among SJS and TEN patients in our study. We had more female patients in the TEN group and more male patients in the SJS group, which is in concordance with the study from West Germany.[6]

Overall, in our study, antimicrobials were the most common group of drugs causing SJS and TEN. But considering the mucocutaneous reactions individually, most of our SJS cases were due to NSAIDs and majority of TEN cases were due to antimicrobials. This is also in concordance with the study done in West Germany[6] which showed antibiotics in 42% of TEN cases and analgesics in 33% of SJS cases. Antibiotics, mainly beta-lactams, were the most common cause of SJS/TEN in Wong et al.'s study.[9] Though a study from France[8] showed NSAIDs as the most common implicated group, some Indian studies[5] have shown anticonvulsants as the most frequently implicated drugs. Nanda and Kaur[10] observed that developing countries have a higher incidence of TEN due to antituberculous drugs. Chan et al.[11] reported antibacterials such as aminopenicillins, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim as the commonest causative drugs for SJS and TEN.

Our study had one patient each of SJS/TEN due to amlodipine and P. amarus (kizhanelli), which is rarely reported in literature. In the amlodipine induced SJS case, no other etiology was found than amlodipine which the patient had taken for 3 months. Calcium channel blockers are known to have a longer reaction time ranging from 2 weeks to 3 months[12,13] as in our case who had a reaction time of 3 months. A case of TEN induced by kizhanelli (P. amarus), an Indian herb used more frequently in many parts of the country for hepatitis, was also observed in our study. Siddha medication and Chinese herbs induced SJS/TEN have been reported previously also.[1] Past history of drug reaction was present in seven TEN cases, of which only two had drug eruption to the same drug in the past and the rest had reaction to a different group of drug and the type of drug reaction was also different. Nearly four of our patients had received radiotherapy for their malignancy prior to occurrence of SJS/TEN as cancer and/or radiotherapy increases the risk of SJS/TEN to anticonvulsants.[1]

The mean reaction time in our study was 6 days. Majority of them had manifested within 7 days of drug intake which is similar to other studies. Noel et al.[14] observed 2–3 weeks for TEN and 1–3 weeks for SJS, and Devi et al.[5 noticed less than 1 week in 44% of cases, between 1 and 2 weeks in 32% of cases, and between 2 and 3 weeks in the remaining 24% of cases of SJS/TEN. Yamane et al.[7] showed that more than half (67.6% ofSJS, 80.0% of TEN) of the patients developed symptomswithin 2 weeks. Roujeau et al.[8] observed a reaction time of 10.2–12 days for TEN cases. The prodromal symptoms were similar as in other studies. Anaphylaxis was noticed in one of our SJS patient. Scalp involvement was noticed in four of our TEN cases.

Mucosal lesions preceded the onset of skin lesion in nearly half of our patients. In a Taiwanese study,[15] 46.7% of patients had mucosal involvement affecting the buccal mucosa, pharynx, tongue, lips, anogenital region, esophagus, colon, nasal cavity and conjunctiva.

Most of our patients had raised ESR and leukocytosis due to neutrophilia. Only three patients had eosinophilia. Three of our TEN patients developed thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, and two patients had neutropenia. Increased liver enzymes were seen in 18 of our cases. As per Yaman et al.'s[7] study in SJS/TEN, hepatitis was the most common complication. Twenty-four cases (46.2%) of SJS and 41 cases (63.1%) of TEN had hepatitis, suggesting that SJS could cause more severe hepatitis than TEN. Nearly 50% of the patients had ocular sequelae in the form of symblepharon, conjunctivitis, corneal scarring and xerosis. Corneal scarring was treated with amniotic membrane transplant. Kaposi's varicelliform eruption developing over the lesions of SJS/TEN occurred in three of our patients, which to our knowledge has not been reported earlier. Kardaun et al.'s[16] study has shown that short-term dexamethasone pulse therapy, given at an early stage of the disease, may contribute to a reduced mortality rate in SJS/TEN with-out increasing healing time as noticed in our study. Mortality rate was high in the cases with chronic co-morbid illnesses like carcinoma, cranial irradiation, diabetes mellitus, HIV, and abnormal laboratory parameters.

Conclusion

Antimicrobials and NSAIDS are the common offending agents for SJS/TEN, and hence, patients who have previous history of drug allergy should strictly avoid over-the-counter medications. Drugs like analgen, Vicks action 500 are banned globally but are available in India and hence strict regulations are needed. Early withdrawal of the offending agent and definitive treatment of SJS/TEN and multispecialty care may reduce the morbidity, mortality rates, and thereby, duration of hospital stay.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Breathnach SM. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004. pp. 53, 1-53–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. A clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avakian R, Pharm D, Flowers FP, Araujo OE, Ramos-Caro FA. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma VK, Sethuraman G, Minz A. Stevens Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and SJS-TEN overlap: A retrospective study of causative drugs and clinical outcome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:238–40. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.41369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devi K, George S, Criton S, Suja V, Sridevi PK. Carbamazepine - The commonest cause of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A study of 7 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:325–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schöpf E, Stühmer A, Rzany B, Victor N, Zentgraf R, Kapp JF. Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome An Epidemiologic Study From West Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:839–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1991.01680050083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamane Y, Aihara M, Ikezawa Z. Analysis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and Toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japan from 2000 to 2006. Allergol Int. 2007;56:419–25. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-07-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roujeau JC, Guillaume JC, Fabre JP, Penso D, Fléchet ML, Girre JP. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell Syndrome): Incidence and drug etiology in France, 1981-1985. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.126.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong KC, Kennedy PJ, Lee S. Clinical manifestations and outcomes in 17 cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:131–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan HL, Stern RS, Arndt KA, Langlois J, Jick SS, Jick H, et al. The incidence of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanda A, Kaur S. Drug induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in developing countries. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioulios P, Charalampos M, Efrossini T. The spectrum of cutaneous reactions associated with calcium antagonists: A review of the literature and the possible etiopathogenic mechanisms. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stern R, Khalsa J. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with calcium-channel blockers. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:829–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noel MV, Sushma M, Guido S. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients in a tertiary care center. Indian J Pharmacol. 2004;36:292–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam NS, Yang YH, Wang LC, Lin YT, Chiang BL. Clinical characteristics of childhood erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Taiwanese children. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:366–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kardaun SH, Jonkman MF. Dexamethasone Pulse Therapy for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:144–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]