Abstract

Background:

Topical corticosteroids were first introduced for use in 1951. Since then uncontrolled use (abuse) has caused many different reactions resembling rosacea – steroid dermatitis or iatrosacea. Multiple pathways including rebound vasodilatation and proinflammatory cytokine release have been proposed as the mechanism for such reactions.

Aim:

The aim was to study the adverse effects of topical steroid abuse and the response to various treatment modalities.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred patients with a history of topical steroid use on face for more than 1 month were studied clinically and various treatments tried.

Results:

The duration of topical corticosteroid use varied from 1 month to 20 years with an average of 19.76 months. Majority of patients were using potent (class II) topical steroids for trivial facial dermatoses. The common adverse effects were erythema, telangiectasia, xerosis, hyperpigmentation, photosensitivity, and rebound phenomenon. No significant change in laboratory investigations was seen.

Conclusion:

A combination of oral antibiotics and topical tacrolimus is the treatment of choice for steroid-induced rosacea.

Keywords: Topical corticosteroids, rosacea, rebound phenomenon

Introduction

Topical corticosteroids were first introduced for use in 1951.[1] Since then uncontrolled use (abuse) has been a common problem. The excessive, regular use of topical fluorinated steroids on the face often produces an array of skin complications, including an eruption clinically indistinguishable from rosacea – ‘steroid-induced rosacea’ or ‘iatrosacea’.[2,3] This dermatosis is known by various names like light-sensitive seborrheid, perioral dermatitis, rosacea-like dermatitis and steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea.[4–10] Steroid-induced rosacea is characterized by centrofacial, perioral, and periocular monomorphic inflammatory papules and pustules distributed in areas that have been chronically exposed to topical steroids, especially of fluorinated type. The appearance is of a flaming red, scaly, papule-covered face (red face syndrome).[11] If left untreated, permanent skin atrophy and telangiectasia can result. Treatment involves discontinuation of the steroid and administration of oral tetracycline or macrolides and non-steroidal topical preparations. Once therapy is begun, clearing of the lesions may take several months.

Methods

Two hundred patients with steroid rosacea attending the dermatology OPD of SKIMS Medical College Hospital were studied from June 2007 to November 2008 after taking informed consent. Ethical clearance from the SKIMS review board was taken. Inclusion criteria for patients were the history of use of any type of topical corticosteroid on face for more than 1 month. Patients with natural rosacea and those denying history of topical steroid use were excluded from the study. A proper history was taken from patients regarding the duration of topical steroid use (in months); type and potency[12] of steroid used; indication, source of prescription, and mode of steroid use; and pruritus, burning, dryness, flushing, photosensitivity, and rebound phenomenon.

Patients were thoroughly examined for the type of skin (Fitzpatrick I–VI), site, erythema (mild, moderate, severe), xerosis, scaling, telangiectasia, hyper- or hypopigmentation, atrophy, wrinkles, comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, and hirsutism. Additional symptoms and signs of skin diseases were noted. The general physical and systemic examination was done on all patients. Routine laboratory investigations like hemogram, liver and renal function tests, blood sugar, and serum cortisol were carried on all patients besides the specific investigations, where required.

Various treatment modalities tried in these patients include oral antibiotics like tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, and azithromycin. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory calcineurin inhibitors like topical tacrolimus along with emollients, calamine, and oral and topical vitamin C and E were also used. Patients being treated were instructed to avoid all topical preparations (including those containing corticosteroids or antibiotics) and factors known to exacerbate rosacea (caffeine, spicy foods, hot beverages, alcohol, fluorinated toothpastes and preparations).

Results

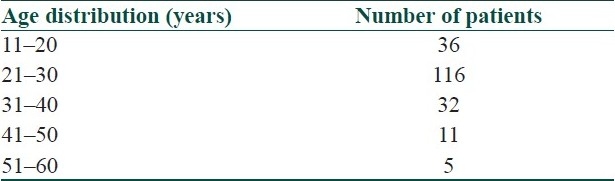

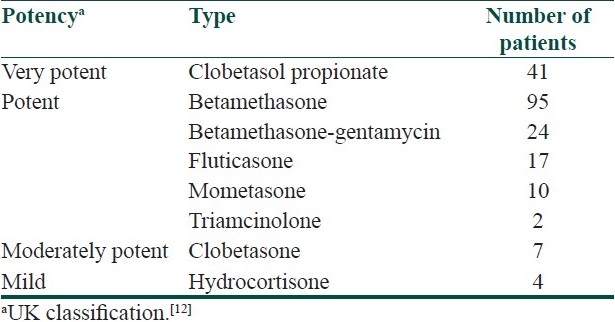

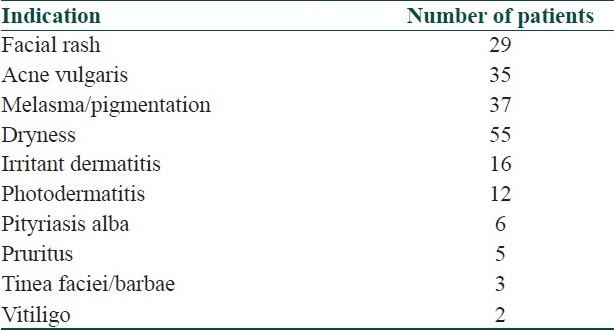

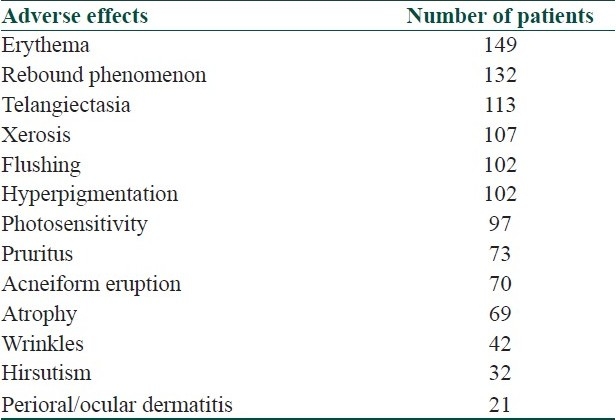

Among the 200 patients studied, 56 were male and 144 female. The age distribution of patients is shown in Table 1. The rural–urban ratio was 116:84, and 164 patients belonged to middle class, 28 to lower, and 8 to upper socioeconomic class. Majority of the patients were housewives, followed by students, government employees, businessmen, farmers, and others. The duration of topical corticosteroid use varied from 1 month to 20 years with an average of 19.76 months. Steroids of different types and potencies used by the patients are shown in Table 2. Topical steroids for facial use were prescribed by chemists in 51, relatives or friends or self in 60, physicians or general practitioners in 51, and by dermatologists in 12 patients. Various indications for which steroids were used are delineated in Table 3. The mode of topical steroid use was twice daily in 44, once daily in 120, alternate day in 20, and twice a week in 16 patients. The adverse effect profile of chronic topical steroid use is shown in Table 4. Majority of the selected patients gave the classic history of chronic steroid exposure with the clinical findings of erythematous facial dermatitis, typically flaring on discontinuation of the steroid. Those patients with a prolonged duration of topical steroid use and those using potent or very potent steroids were more symptomatic. No significant change in laboratory investigations was seen.

Table 1.

Age distribution of patients using topical corticosteroids on face

Table 2.

Potency and type of topical corticosteroids used

Table 3.

Indications of topical corticosteroid use

Table 4.

Adverse effect profile of chronic topical corticosteroid use

Most of the patients with severe symptoms who were given oral azithromycin 500 mg in the form of weekly pulse therapy (3 tabs per week for 4–6 weeks) or oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 4–6 weeks, along with topical tacrolimus 0.03% ointment twice daily showed a good response in around 2–3 months. Those with mild symptoms were given only topical tacrolimus for 4–6 weeks and were symptom free within 4 weeks. Emollients, calamine, and oral vitamin E and C had additional beneficial effect in relieving the symptoms in patients with prominent atrophy and telangiectasia.

Discussion

The excessive, regular use of topical corticosteroids on the face is a common problem, often producing an array of skin complications, including an eruption clinically indistinguishable from rosacea. The occurrence of this unexpected dermatosis might not be merely a medical problem but also a social problem.[10] The patients may start using steroids for some trivial dermatosis like seborrheic dermatitis and are often prescribed by friends and relatives.[2,3] At first the vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects of the steroids result in what seems to be clearance of the primary dermatitis but persistent use leads to epidermal atrophy, degeneration of dermal structure and collagen deterioration after several months. In the end, the skin has the appearance of rosacea and is rendered extremely vulnerable to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.[5,6] Continued or overuse of steroids can result in thinning of the skin as well as skin dependency on the steroid. The appearance is of a flaming red, scaly, papule-covered face.[7–9] Multiple pathways including rebound vasodilatation and proinflammatory cytokine release by chronic intermittent steroid exposure induce rosacea-like eruption.[11] The average duration of treatment required to produce adverse effects in most cases is 6 months or more, but it varies and is also potency dependent.[9,10] Our study showed a very good response to the combination of oral antibiotics and topical tacrolimus in severe cases and to topical tacrolimus alone in mild cases. Tacrolimus exerts its immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effect by blocking T-cell activation. However, in contrast to topical corticosteroids, tacrolimus does not induce vasoconstriction or atrophy.[11] We conclude that trivial skin dermatosis, especially on face, should not be treated with topical corticosteroids and the combination of oral antibiotics and topical tacrolimus is the treatment of choice for steroid-induced rosacea. However, further studies using a larger number of patients are required to confirm our results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Ljubojeviae S, Basta JA, Lipozeneiae J. Steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea: aetiopathogenesis and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2002;16:121–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00388_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornstein OP. Perioral (rosaceiform) dermatitis - a ‘modern’ problem disease. Internist. 1975;16:27–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litt JZ. Steroid-induced rosacea. Am Fam Physician. 1993;48:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frumes GM, Lewis HM. Light sensitive seborrheid. Arch Dermatol. 1957;75:245–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550140089014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihan R, Ayres S. Perioral dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:803–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1964.01590300031010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneddon I. Iatrogenic dermatitis. Br Med J. 1969;4:49–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5674.49-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leyden S, Thew M, Kligman AM. Steroid Rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1974;11:619–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinegac LZ, Zmegac Z. So called perioral dermatitis. Lijec Vjes. 1976;98:629–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sneddon I. Adverse effect of topical fluorinated corticosteroids in rosacea. Br Med J. 1969;1:671–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5645.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathi S. Abuse of topical steroid as cosmetic cream: A social background of steroid dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:154–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman D. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of Steroid-Induced Rosacea.A preliminary report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:995–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashworth J. Potency classification of topical corticosteroids: modern perspectives. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl. 1989;151:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]