Abstract

Background:

Glucantime is regarded as the first-line treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL); however, failure to treatment is a problem in many cases.

Aim:

The aim was to evaluate the therapeutic effect of glucantime in CL complicated with secondary bacterial infection compared to uncomplicated lesions.

Methods:

This experimental study was performed in Skin Diseases and Leishmaniasis Research Center, Isfahan, Iran. A total of 161 patients enrolled in the study had CL confirmed by positive smear of lesions. All the patients were treated with systemic glucantime for 3 weeks and followed for 2 months. Response to treatment was defined as loss of infiltration, reepithelization, and negative smear. Depending on the results of bacterial cultures, the lesions were divided into two groups and the efficacy of glucantime was compared.

Results:

A total of 123 patients (76.4%) were negative, and 38 patients (23.6%) were positive for secondary bacterial infection. In groups with negative bacterial culture response to treatment was 65% (80 patients) and in the other positive group, it was 31.6% (12 patients), with a difference (χ2 = 13.77, P < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Therapeutic effect of glucantime showed a decrease in CL lesions with secondary bacterial infection. Therefore, in the cases of unresponsiveness to treatment, the lesions should be evaluated for bacterial infection, before repeating the treatment.

Keywords: Bacterial infection, cutaneous leishmaniasis, glucantime

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an endemic parasitic disease in Iran. It is so prevalent that in some villages up to 70% of the population have at least one leishmaniasis scar.[1] Pentavalent antimony compounds including meglumine antimoniate (glucantime) and sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) are regarded as the first-line treatment of this condition.[2] They are normally effective in 70–85% of cases when given in an adequate dose and duration.[3] Antimonial unresponsiveness in human leishmaniasis has long been recognized as a serious clinical problem, and its prevalence appears to be increasing.[4] In such cases, repeating the treatment for several courses leads to increasing the resistance to these drugs.[4]

In this study, anti-leishmanial activity of glucantime was evaluated in CL lesions complicated with secondary bacterial infection and non-complicated lesions.

Methods

This experimental study was carried out in Skin Diseases and Leishmaniasis Research Center, Isfahan, Iran. The participants enrolled in the study had CL confirmed by positive smear of their lesions. They were of both sex and different age groups. The patients or their guardians signed a consent form after being informed about the study. Those with underlying disease, pregnant women, children under 5 years old, previous treatment with glucantime, and those with more than one lesion or lesions lasting for more than 6 months were excluded from the study. For bacteriological examination, the center of lesions were scraped using a sterile swab and the samples were cultured on a blood agar medium inside a disposable plastic plate. The inoccula were spread on the blood agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Smears from each of the morphologically different colonies were observed on the blood agar, then heat fixed, treated with Gram stain, and examined microscopically. Bacteria were identified from their form, size, reaction to Gram stain, and colony characteristics on the culture medium.

The patients were treated with glucantime at 20 mg/kg/day dosage for 20 days and followed for a period of 2 months. Good response to treatment was defined as the loss of infiltration, reepithelization, and negative smear. Poor response was defined as unchanging size of the lesions without reepithelization and positive smear at the end of the study. Regarding the results of cultures, the patients were divided into positive and negative groups. Glucantime activity was compared between two groups by Chi-square test using SPSS software (Chicago, USA).

Results

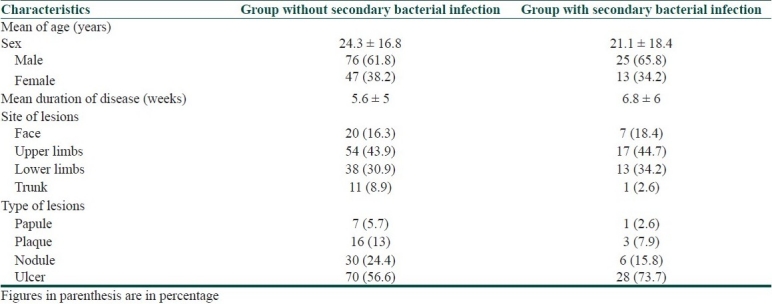

A total of 161 patients (101 male and 60 female) completed the study. The mean age was 23.6 ± 17.3, and the mean of disease duration was 5.6 ± 5.3 weeks. The mean size of lesions was 23 ± 0.9 mm. Characteristics of patients in two groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients in the two study groups

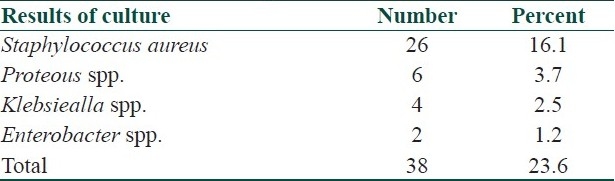

Results of bacterial culture were negative in 123 patients (76.4%) and positive in 38 patients (23.6%). In the group with negative culture, good response to glucantime was observed in 80 patients (65%) and poor response observed in 43 patients (35%). In the group with positive culture, 12 patients (31.6%) had good response and 26 patients (68.4%) had poor response (χ2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). The results of isolated bacterial species are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bacterial species isolated from lesions

Discussion

This study showed that there was a significant difference between therapeutic effect of glucantime in the lesions of CL complicated with secondary bacterial infection and uncomplicated lesions in a way that in lesions with secondary bacterial infection the efficacy of glucantime was decreased [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion infected with secondary bacterial infection before treatment with glucantime

Figure 2.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion infected with secondary bacterial infection after treatment with glucantime

Pentavalent antimonial in the form of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate (glucantime) has been recommended as a first-line treatment of CL. These drugs are administrated parenterally at dosage of 10–20 mg/kg/day for 10–30 days, depending on the clinical form of the disease.[5] Unfortunately, failure to treatment in kala azar, mucosal leishmaniasis, and some forms of CL is becoming a problem in many endemic areas, occurring in 5–70% of the patients. In some instances, this could be attributed to reinfection or immunologic, physiologic, and pharmacokinetic deficiencies in the host.[5] In a previous study, the futility and dangers of repeating antimonial treatments were emphasized.[4] In a study from Mexico, the pathogenic role of bacteria in skin lesions of patients with chiclero's ulcer (one of the forms of CL due to Leishmania Mexicana), reluctant to antimonial treatment was determined which suggested the need of elimination of bacterial infection before starting treatment.[6] In another study from Iran, resistance to glucantime was reported in 20 out of 185 patients (10.8%) in a region where anthroponotic CL is endemic[7] and one study reported 8.1% resistance in a region of zoonotic CL.[8] Another study showed that patients infected with L. tropica have more drug resistance and those infected with L. major have more drug sensitivity to glucantime.[9]

The prevalence of superimposed bacterial infection in CL in two other studies done in Iran was 26.5% and 21.8%. Staphylococcus aureus was the most prevalent organism in these lesions.[10,11] This study showed decreased activity of glucantime in lesions of CL infected with secondary bacterial infection with the prevalence of 23.6%. The most prevalent-isolated organism was Staphylococcus aureus confirming the results of previous studies.

Regarding the prevalence of secondary bacterial infection and decreasing the glucantime efficacy, in the cases of unresponsiveness to treatment with antimonial compounds, evaluation of secondary bacterial infection is recommended, and antibiotic therapy before repeating the treatment is suggested.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Professor Klas Nordlind for his suggestions during writing this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Hatman GR, Riyad M, Bichichi M, Hejazi SH, Guessous Idrissi N, Ardehali S, et al. Isoenzyme characterization of Iranian Leishmania Isolates from cutaneous leishmaniasis. Iran J Sci Technol. 2005;29:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croft SL, Sundar S, Fairlamb AH. Drug Resistance in Leishmaniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:111–26. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.111-126.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Momeni Ali Z, Aminjavaheri M. Successful treatment of non-healing cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis, using Combination of meglumine antimoniate plus alloporinol. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Orisini S. Decreased Sensitivity to meglomine antimoniate (Glucantime) of Leishmania infantum isolated from dogs after several courses of drug treatment. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:613–20. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1992.11812717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grogi M, Thomason TN, Franke ED. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis: its implications in systemic chemotherapy of cutaneous and mucocutaneous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;47:117–26. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaae-Marquez AP, Lezoma-Davila CM. Detection of pathogenic bacteria in skin lesions patients with chiclero's ulcer, Relactant response to antimonial treatment. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:1993–5. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000800021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadighi R, Mohebali M, Boucher P, Hajjaran H, Khamesipour A, Ouellette M. Unresponsiveness to Glucantime treatment in iranian cutaneous leishmaniasis due to drug-resistant leishmania tropica parasites. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilfroushzadeh MA, Ansari N, Derakhshan R. Frequency of resistance to systemically administered meglumin antimoniate (Glucantime) in patients with acute cutaneuse leishmaniasis: A cross-sectional study. Iran J Dermatol. 2006;8:457–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motazedian M. Study of glucantime resistance in cutaneous leishmaniasis by PCR-RFLP method in Shiraz, Iran? [last cited on 2004 May]. Available from: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/eccmid14/abstract.asp?id=14270#top .

- 10.Edrissian GH, Mohammadi M, Kanani A, Afshar A, Hafezi R, Ghorbani M, et al. Bacterial infections in suspected cutaneous leishaniasis lesions. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;88:473–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziaei H, Sadeghian G, Hejazi SH. Distribution frequency of pathogenic bacteria isolated from cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Korean J Parasitol. 2008;46:191–3. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2008.46.3.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]