Abstract

Background:

Although cryotherapy is still the first-line therapy for solar lentigines, because of the side effects such as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), especially in patients with darker skin types, pigment-specific lasers should be considered as a therapy for initial treatment.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of cryotherapy compared with 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) with cutaneous compression in the treatment of solar lentigines.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-two patients (skin type II–IV) with facial or hand lentigines participated in this study. Lesions of one side of the face or each hand were randomly assigned and treated with either cryotherapy or PDL. Treatments were performed with radiant exposures of 10 J/cm2 , 7-mm spot size and 1.5 ms pulse duration with no epidermal cooling. Photographs were taken before treatment and 1-month later. The response rate and side effects were compared.

Results:

PDL was more likely to produce substantial lightening of the solar lentigines than cryotherapy, especially in skin type III and IV (n = 8, n = 9; P < 0.05), but might be no difference in type II (n = 5; P > 0.05). PIH was seen only in cryotherapy group. PDL group had only minimal erythema. No purpura was observed.

Conclusion:

PDL with compression is superior to cryotherapy in the treatment of solar lentigines in darker skin types.

Keywords: Cryosurgery, cryotherapy, lentigo, pulsed dye laser

Introduction

Solar lentigines are well-circumscribed or irregularly shaped dark brown or black macules that occur on sun-exposed areas, predominantly on dorsal aspects of the hands and the face.[1] Because of the negative social impact on quality of life, most of the patients seek treatment.

There are two types of treatment: (1) physical therapies, which include cryotherapy, laser therapy, intense pulsed light (IPL), and chemical peeling and; (2) topical therapies such as hydroquinone and tretinoin. Cryotherapy is currently the first-line therapy for solar lentigines. Although it is inexpensive and effective, side effects such as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) limit its use especially in darker Fitzpatrick's skin types. Because of the broad absorption spectrum of melanin (351-1064 nm), multiple type of lasers (e.g., pulsed dye laser (PDL), Q-switched ruby, Q-switched Nd:YAG) have been used in the treatment of solar lentigines.[2] Although PDL is a gold standard laser treatment for many superficial cutaneous vascular lesions,[3] several studies suggest the good efficacy of PDL with compression in the treatment of solar lentigines.[4–10] To our knowledge, there are no published studies comparing cryotherapy with 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) and cutaneous compression in the treatment of solar lentigines. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of these modalities in the treatment of solar lentigines.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-four patients with Fitzpatrick's skin type II-IV with facial or hand lentigines were enrolled in this evaluator-blinded randomized clinical trial. Two patients were lost to follow-up. All patients, who completed follow up, were between the ages of 28 and 67 years (mean, 51.2 years; 20 females and 2 males) and had solar lentigines on their face or hands based on clinical diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: pregnancy, recent sun tanning, previous laser or topical treatments, history of oral retinoid treatment with in the previous 6 months, known photosensitivity or taking photosensitizing medication and history of vitiligo or psoriasis or keloid formation. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, and was confirmed by the ethical committee of our university. All patients signed informed consent forms. Lesions of one side of the face or each hand were randomly assigned and treated with either cryotherapy or 595-nm PDL (Vbeam, Candela Corporation, Wayland, MA) with cutaneous compression. Treatments were performed with radiant exposures of 10 J/cm2 , 7-mm spot size, and 1.5-ms pulse duration with no epidermal cooling.[4] During each pulse, proper compression with convex surface of a fused-silica meniscus optical element with zero optical power was used to push the blood to the outside of laser treatment area and prevent purpura. We used 1–3 laser passes until darkening of the lesion. Cryotherapy was done with liquid nitrogen using cryospray. The cryospray was applied for 3–5 s on each lesion from a distance of 3 cm from the lesion. Both procedures were well-tolerated by all patients without topical anesthesia. Patients were asked to avoid sun exposure and use sunscreen on their hands and face. Before treatment and 1-month later, digital photographs were taken with the same camera. Two blind observers (both board-certified dermatologists) were asked to grade each treated site (hands or face) according to “before” and “after” pictures. The degrees of lightening of the lentigines were graded as either poor (minimal change with lightening of 0%–25%), mild (slight improvement with lightening of 26%–50%), moderate (though quite improved, can be differentiated from the surrounding healthy skin with lightening of 51%–75%), or marked (difficult to differentiate from the surrounding healthy skin with lightening of 76%–100%). The side effects including PIH and hypopigmentation, post-PDL erythema, atrophic and hypertrophic scar were recorded in a follow-up session after 1 month.

Data were analyzed with SPSS 16.0 software using Wilcoxon-signed-ranks test and Chi-square test. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Of the original 24 patients, 22 patients (20 females and 2 males) participated in this study. Two female patients were unable to follow up due to traveling issues. The frequency of Fitzpatrick's skin types were as follows: five cases (22.7%) skin type II, eight cases (36.4 %) skin type III and nine cases (40.9 %) skin type IV. About two-thirds (68.2%) of the lentigines were on the dorsum of the hands and 31.8% on the face.

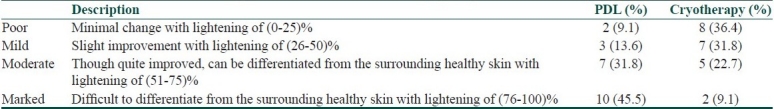

After 1 month, PDL with compression produced more than 75% lightening (marked improvement) in 10 patients (45.5%) compared with 2 patients (9.1%) in the cryotherapy group [Table 1]. Statistical analysis showed a significant difference (P < 0.05; [Figures 1 and 2], respectively).

Table 1.

Response to treatment in study groups Treatment Response

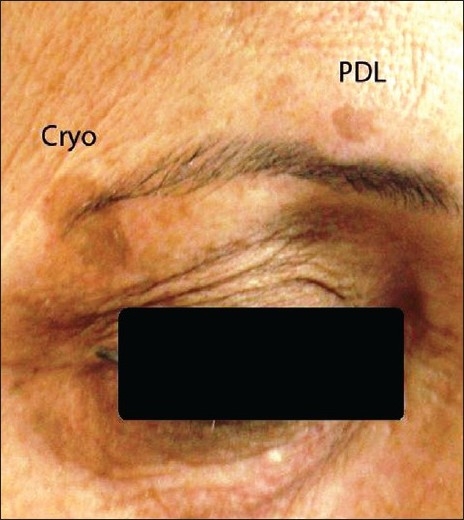

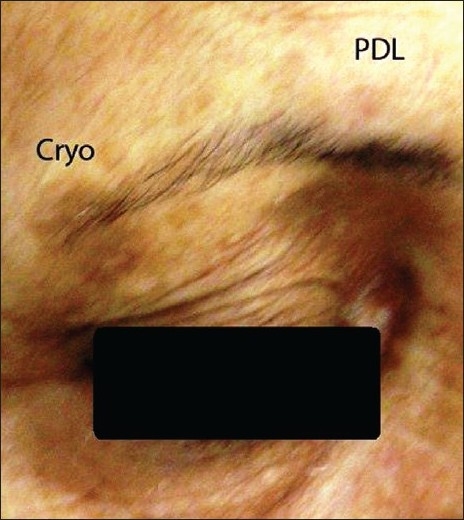

Figure 1.

Before treatment

Figure 2.

After treatment: marked improvement of medial lesion with PDL with compression after 1 month

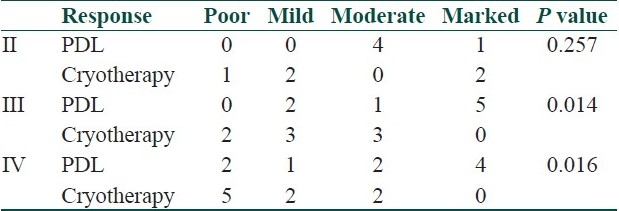

PDL response showed a significant difference in patients with Fitzpatrick's skin type III and IV (n = 8, n = 9; P < 0.05). In contrast, there might be no significant difference between PDL and cryotherapy response in Fitzpatrick's skin type II (n = 5; P > 0.05) [Table 2]. Side effects were only post-PDL minimal erythema (after 1 month) in six patients (27.3%) of the PDL group and only (PIH) in eight patients (36.4%) of the cryotherapy group. There were no other side effects such as atrophic and hypertrophic scar or purpura or hypopigmentation.

Table 2.

Number of the patients according to treatment response in each skin type Skin Type

Discussion

Topical therapies of solar lentigines have fewer side effects but usually take longer than physical therapies to achieve a good result. Lasers and cryotherapy are the more popular modalities in the physical therapies.[2] These are frequently used with excellent clinical success rate; however, these types of therapies should be balanced against associated side effects.[11] Cryotherapy is one of the most widely used and effective treatments in this field which is inexpensive and easily accessible. The principle of treatment in cryotherapy in solar lentigines is melanocytes vulnerability to cold injury, which can destroy them at temperatures of –4°C to –7°C.2 In contrast, squamous cells can resist injury until down to –20°C.[11]

Melanin can absorb laser beams in a wide spectral range (351–1064 nm).[2] Accordingly,various types of lasers such as pulsed dye (595 nm),[4–10] frequency-doubled Nd:YAG (532 nm),[12] KTP (532 nm),[13] Q-switched ruby (694 nm),[8] Q-switched and long-pulse Alexandrite (755 nm),[13,14] and Q-switched Nd:YAG (1064 nm)[2] have been used to treat solar lentigines.

PDL has been used for vascular lesions for many years.[3] Recently, this laser has been usedsuccessfully for the treatment of epidermal pigmented lesions such as solar lentigines, freckles, and seborrheic keratosis with some modifications.[4] Using skin compression during PDL removes the blood from the targeted treatment area, effectively eliminating hemoglobin as a competing target chromophore, and thereby minimizing the risk of purpura production, and allowing for the use of effective radiant exposure range for treating epidermal pigmented lesions (9–10 J/cm2 , 1.5-ms pulse duration).[4–5] Epidermal cooling, which is usually used during treatment of vascular lesions with PDL, decreases the interaction between laser energy and the superficial pigmented lesion.[4] Similar to previous studies,[4–10] epidermal cooling was not used in our study and no epidermal burning was recorded. Various methods of skin compression for preventing purpura have been used in previous studies. Kono et al. attached a flat glass to the laser's hand-piece in their first study.[8] Later they found that attaching a convex glass instead of flat one allows for a more uniform blood displacement during skin compression from the irradiated field and better preventing purpura.[6] Garden et al. used convex surface of a fused-silica meniscus optical element with zero-optical power for compressing the skin during laser treatment.[4] By using this compression technique, no purpura was detected in our patients.

Lentigines are often treated only for cosmetic reasons. Therefore, complications in such therapeutic procedures are particularly important. Darker skin patients such as Asians have higher epidermal melanin content and are more likely to develop erythema and PIH, which can be considered as a default pathophysiologic response to cutaneous injury in these patients. Several factors contribute to the development of PIH, including increased melanocytic activities, dermal melanophages, and hemosiderin deposition secondary to hemorrhage. The severity of PIH is related to the degree of inflammation and extent of disruption of the dermo-epidermal junction caused by endogenous inflammatory skin disorders or iatrogenic sources such as lasers and cryotherapy.[8,15] We have PIH in our patients only in cryotherapy group suggesting that inflammatory response which is responsible for developing PIH may be more prominent in cryotherapy than PDL group.

Although Q-switched Ruby and Alexandrite are highly effective in the treatment of lentigines, the risk of complications such as erythema, blistering and PIH in darker skin types (Fitzpatrick's skin type III and IV) in these lasers are higher.[8] Kono et al. compared Q-switched ruby laser (QSRL) versus PDL with compression for treating facial lentigines in Asian (Fitzpatrick's skin type III and IV). They found that PDL with compression is more effective than QSRL with substantially less side effects. PIH were detected only in some patients in the QSRL group. This study showed that PDL with compression is superior to QSRL for treating pigmented lesions in darker Fitzpatrick's skin types.[8] In our study, no PIH was seen in the PDL group.

Todd et al. compared three type of lasers (frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, krypton laser, and 532-nm diode-pumped vanadate laser), and cryotherapy in the treatment of solar lentigines. This study showed that laser therapy is superior to cryotherapy. Best results were achieved by Nd:YAG laser with very few side effects.[12] It is difficult to directly compare these results with our study, as the types of the lasers used, are different. However, similar to Todd study, the improvement in our patients in laser group wassuperior to cryotherapy (P < 0.05) with fewer side effects.

Raziee et al. compared cryotherapy versus trichloroacetic acid 33% (TCA) in solar lentigines treatment and found better results with cryotherapy. PIH was the major complication in both treatments especially in Fitzpatrick's skin type III and IV.[16] In our study, we detected PIH only in cryotherapy group especially in darker skin types.

Our study is a pilot one to compare efficacy and safety of a popular therapeutic modality like cryotherapy with a new laser method, PDL 595-nm with compression, in the treatment of solar lentigines. Therefore, it seems that confirming these results needs more studies with larger population size.

Conclusion

Finally, it seems that the major factor in determining the therapeutic modality for solar lentigines is Fitzpatrick's skin type. In darker skin types such as skin type III and IV, there is a significant difference between PDL and cryotherapy in achieving good results. However, when the patient has lower skin types such as skin type II, there may be no difference between the two therapeutic methods. In addition, side effects in PDL with compression are minimal (only minimal erythema in a few cases without PIH or purpura) as compared with cryotherapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Barnhill RL, Rabinovitz H. Dermatology. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Solar lentigines. 2nd ed. USA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. p. 1716. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortonne JP, Pandya AG, Lui H, Hexsel D. Treatment of solar lentigines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsai S, Roos S, Hammes S, Raulin C. Pulsed dye laser: what's new in non-vascular lesions? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:877–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garden JM, Bakus AD, Domankevitz Y. Cutaneous Compression for the Laser Treatment of Epidermal Pigmented Lesions with the 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:179–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauvar ANB, Rosen N, Khrom T. A Newly Modified 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser with Compression Handpiece for the Treatment of Photodamged Skin. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:808–13. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kono T, Chan HH, Groff WF, Sakurai H, Takeuchi M, Yamaki T, et al. Long-Pulse Pulsed Dye Laser Delivered with Compression for Treatment of Facial Lentigines. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:945–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galeckas KJ, Collins M, Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS. Split-Face Treatment of Facial Dyschromia: Pulsed Dye Laser with a compression Handpiece versus Intense Pulsed Light. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:672–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kono T, Manstein D, Chan HH, Nozaki M, Anderson RR. Q-switched Ruby Versus Long-Pulsed Dye Laser Delivered with Compression for Treatment of Facial Lentigines in Asians. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:94–7. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galeckas KJ, Ross EV, Uebelhoer NS. A Pulsed Dye Laser with a 10-nm Beam Diameter and a Pigmented Lesion Window for Purpura-Free Photorejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:308–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pootongkam S, Asawanonda P. Purpura-free treatment of lentigines using a long-pulsed 595 nm pulsed dye laser with compression handpiece: a randomized, controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hexsel DM, Mazzuco R, Bohn J, Borges J, Gobbato DO. Clinical comparative study between cryotherapy and local dermabrasion for the treatment of solar lentigo on the back of the hands. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:457–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd MM, Rallis TM, Gerwels JW, Hata TR. A comparison of 3 lasers and liquid nitrogen in the treatment of solar lentigines. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:841–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.7.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassichis BA, Swamy R, Dayan SH. Use of the KTP laser in the treatment of Rosace and solar lentigines. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20:77–83. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trafeli JP, Kwan JM, Meehan KJ, Domankevitz Y, Gilbert S, Malomo K, et al. Use of a long-pulse alexandrite laser in the treatment of superficial pigmented lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1477–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho SGY, Chan HHL. The Asian dermatologic patient: Review of common pigmentary disorders and cutaneous diseases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:153–68. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200910030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raziee M, Balighi K, Shabanzadeh-Dehkordi H, Robati RM. Efficacy and safety of cryotherapy vs.trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of solar lentigines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:316–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]