Abstract

Nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD) -like receptors (NLRs) and retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG) -like receptors (RLRs) are recently discovered cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors sensing mainly bacterial components and viral RNA, respectively. Their importance in various cells and disorders is becoming better understood, but their role in human tonsil-derived T lymphocytes remains to be elucidated. In this study, we evaluated expression and functional relevance of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar CD3+ T lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry, real-time RT-PCR and flow cytometry revealed expression of NOD1, NOD2, NALP1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 at mRNA and protein levels. Because of the limited number of ligands (iE-DAP, MDP, Alum, Poly(I:C)/LyoVec), functional evaluation was restricted to NOD1, NOD2, NALP3 and RIG-1/MDA-5, respectively. Stimulation with the agonists alone was not enough to induce activation but upon triggering via CD3 and CD28, a profound induction of proliferation was seen in purified CD3+ T cells. However, the proliferative response was not further enhanced by the cognate ligands. Nonetheless, in tonsillar mononuclear cells iE-DAP, MDP and Poly(I:C)/LyoVec were found to augment the CD3/CD28-induced proliferation of tonsillar mononuclear cells. Also, iE-DAP and MDP were found to promote secretion of interleukins 2 and 10 as well as to up-regulate CD69. This study demonstrates for the first time a broad range of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar T cells and that NOD1, NOD2 and RIG-1/MDA-5 act synergistically with αCD3 and αCD28 to induce proliferation of human T cells. Hence, these results suggest that these receptors have a role in T-cell activation.

Keywords: CD4/helper T cells (Th cells, Th0, Th1, Th2, Th3, TH17); CD8/cytotoxic T cells; co-stimulation; innate immunity; T cells

Introduction

Using germ-line encoded pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), the innate immune system provides the first line of defence against invading microbes. The innate immune responses then mediate the activation of pathogen-specific adaptive immunity.1 Among the PRRs, the membrane-bound and endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs) have been extensively investigated.2 Studies have shown them to be important in innate and adaptive immunity3–6 and they have been implicated in various diseases.7,8 Recently, two families of cytosolic PRRs have emerged; the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs) and the retinoic acid-inducible gene-1 (RIG)-like receptors (RLRs).9

The human NLRs are a diverse protein family with 23 members, but cognate ligands have only been described for a minority of them. Based on the variable N-terminal effector region the receptors are classified into caspase-activating and recruitment domain-containing NODs, NACHT-, leucine-rich repeat- and pyrine domain-containing proteins (NALPs), baculovirus inhibitor repeat-containing neuronal apoptosis inhibitor proteins (NAIPs) and ICE protease activating factors (IPAFs.)10 The most studied affiliates are NOD1, NOD2 and NALP3, which recognize bacterial cell products γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), muramyl dipeptide (MDP) and multiple stimuli including aluminium adjuvants, respectively.10,11 Despite their recent discovery, studies have revealed that genetic variations in the NLR-encoding genes are associated with susceptibility to a broad range of inflammatory disorders.2 In addition, patients with symptomatic allergic rhinitis exhibit lower levels of NOD1 and NALP3 compared with healthy controls and patients outside the season.12

The available information regarding RLRs is limited and this family consists of three members; retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-1), melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA-5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP-2).13 Both RIG-1 and MDA-5 have been suggested to be involved in the recognition of cytoplasmic viral RNA whereas the ligand for LGP-2 remains to be explored.13

The role of cytosolic PRRs is just beginning to emerge and in the present study we have evaluated the expression and functional activity of a range of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar T lymphocytes. Our data suggest that these receptors form a novel pathway for T-cell activation and are important for further knowledge about the bridging of innate and adaptive immunity.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The following reagents were used: iE-DAP, d-glutamyl lysine (iE-Lys), MDP and MDP control (endotoxin levels < 0·125 EU/ml) together with Poly(I:C)/LyoVec from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). Aluminium hydroxide (Alum), PMA and ionomycin were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). αCD3 and αCD28 were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA) and [methyl-3H]thymidine was from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA).

Antibodies

The following mouse monoclonal antibodies were used: BDCA-2-phycoerythrin (PE) (AC144) from Miltenyi Biotec (Cologne, Germany), CD3-FITC (clone UCHT1), CD19-PE (HIB19) from eBioscience (San Diego, CA), CD4-PE (MT310) and CD8-FITC (DK25) from Dako (Copenhagen, Denmark), CD3-energy-coupled dye (ECD) (UCHT1), CD4-PCy5 (13B8.2), CD8-PE (B9.11), CD14-phycoerythrin (PE) 5.1 (RMO52), CD19-ECD (J3-119), CD45-ECD (J.33) and CD69-ECD (TP1.55.3) from Beckman Coulter (Marseille, France). Unlabelled mouse monoclonal antibodies against NOD2 (isotype: msIgG1, clone: 2D9), NALP1 (msIgG1, Nalpy1-4), NALP3 (msIgG1, nalpy3-b), RIG-1 (msIgG2a, clone not specified) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NOD1, NALP1, NAIP, IPAF, MDA-5, LGP-2 and goat anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (H&L) were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Isolation and culture of cells

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lund University (LU-681-04) and written informed consent was obtained from parents of paediatric patients. Human tonsils were obtained from 28 children undergoing tonsillectomy at Skåne University Hospital (Malmö, Sweden). The tonsils were dissected and homogenized in complete medium comprising RPMI-1640 (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 0·3 g/l l-glutamine, 10% FCS (AH Diagnostics, Aarhus, Denmark) and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Mononuclear cells were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). The lymphocyte-enriched interphase fraction was recovered and resuspended in complete medium. In some experiments, CD3+ T cells were negatively isolated using the magnetic antibody cell sorting magnetic labelling system (Pan T Cell Isolation kit II from Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The isolated cells were routinely screened for expression of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD14, CD19 and CD45 by flow cytometry, revealing highly purified T-cell preparations (> 95% CD3+ cells).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Freshly purified CD3+ T lymphocytes were lysed in RLT® (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) buffer supplemented with 1%β-mercaptoethanol, and stored at −80° until use. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase digestion according to the manufacturer's protocol. The quality and quantity of RNA was determined by spectrophotometry, based on the absorbance ratio 260 nm/280 nm (1·7–2·1 in all samples). Reverse transcription of total RNA was performed using the Omniscript reverse transcriptase kit (Qiagen) and oligo-dT primer (DNA Technology). The cDNA samples were denatured (65° for 5 min), chilled (4° for 5 min) and amplified (37° for 1 hr) using a Mastercycler PCR machine (Eppendorf, Germany).

Real-time PCR was performed using Stratagene Brilliant® QPCR Mastermix (Agilent technology, Santa Clara, CA) and FAM-labelled probes for NOD1 (assay ID Hs01036721_m1), NOD2 (Hs00223394_m1), NALP1 (Hs00248187_m1), NALP3 (Hs00366465_m1), NAIP (Hs03037952_m1), IPAF (Hs00368367_m1), RIG-1 (Hs01058986_m1), MDA-5 (Hs00223420_m1), LGP-2 (Hs01597849_m1) and β-actin (Hs99999903_m1) from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The thermal cycler was set to perform an initial set-up (95° for 10 min) and 45 cycles of denaturation (95° for 15 seconds) followed by annealing/extension (60° for 1 min) using Stratagene Mx3000P (Agilent technology). The mRNA expression was assessed using the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method where the relative amounts of mRNA were determined by subtracting Ct values of NLRs and RLRs from Ct values of β-actin (ΔCt). The amount of mRNA was expressed as 2−ΔCt × 100 000 and presented as mean values ± SEM.3,4

Immunohistological assay

The morphological localization of NLRs and RLRs in tonsillar tissue and purified tonsillar T cells was investigated by immunohistochemical staining. Tonsil preparations were embedded in paraffin and freshly isolated CD3+ T cells were resuspended in fixation solution containing equal amounts of 10% neutral-buffered formalin and 95% alcohol. Fixed cells were centrifuged, the supernatants were removed and the pellets were embedded in paraffin. Thereafter, tonsillar tissue and embedded cells were cut in 3-μm sections and stored at −80° until use. The NLR and RLR proteins were detected using Envision+ System horseradish peroxidase kits (Dako). In short, the sections were incubated with antibodies against CD3 (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), NOD1, NOD2, NALP1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 for 3 hr, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labelled polymer for 30 min, followed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate-chromogen for 5 min. Finally, the slides were mounted in Faramount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Dako). As negative controls, N-series Universal Negative Control Reagents (Dako) or antibody diluent (Dako), were used. To visualize the nucleus, counterstaining using haematoxylin was performed.

Flow cytometry analyses

Flow cytometry analyses were performed on a Coulter Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and live cells were gated based on forward and side scatter properties. Between 20 000 and 40 000 events were collected and data were analysed using Expo32 Analysis software (Beckman Coulter).

Intracellular protein expression analysis

To identify intracellular protein expression of NLRs and RLRs, the Intraprep™ Permeabilization kit (Beckman Coulter) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, freshly isolated cells were fixed using formaldehyde, permeabilized using saponin and thereafter incubated with antibodies against NLRs and RLRs or appropriate isotype controls. The polyclonal antibodies against NOD1, NAIP, IPAF, MDA-5 and LGP-2 were detected using an FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H&L) polyclonal secondary antibody and monoclonal antibodies against NOD2, NALP1, NALP3 and RIG-1 were used together with Alexa Fluor 488 msIgG1 or msIgG2a labelling kits (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). To detect background staining, isotype controls relevant for each antibody were used.12,14

Proliferation assay

Freshly isolated CD3+ T cells or tonsillar mononuclear cells were cultured (1 × 106 cells/ml) in triplicate at 37° in 5% CO2 in complete medium with different concentrations of iE-DAP, iE-Lys, MDP, MDP control, Alum (0·1, 1, 10 μg/ml) or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (0·01, 0·1, 1 μg/ml) in the absence or presence of αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml). The concentrations of αCD3 and αCD28 were chosen based on evaluation of dose-dependency (range 0·1–10 μg/ml for αCD3 and 0·5–5 μg/ml for αCD28). In all experiments, PMA (0·1 ng/ml) and ionomycin (0·5 μg/ml) were used as positive control. According to a kinetic evaluation (0, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120 hr), proliferation was quantified by [methyl-3H]thymidine incorporation (1 μCi/well) after 72 hr using an 18-hr pulse period. Incorporated radioactivity was determined in a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta Liquid Scintillator Counter (Perkin Elmer).

Cytokine secretion assay

Cell-free supernatants of cells stimulated with iE-DAP, MDP, Alum (all 10 μg/ml) or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (1 μg/ml) in the presence of αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml) for 72 hr were assessed for secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2; detection level 7 pg/ml), IL-4 (10 pg/ml), IL-10 (3·9 pg/ml) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ; 8 pg/ml), using ELISA plates from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Regulation of cell surface markers

Freshly isolated tonsillar mononuclear cells were cultured with iE-DAP, MDP, Alum (all at 10 μg/ml) or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (1 μg/ml) in the presence of αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml). After 24 hr, expression of CD69 on CD4+ and CD8+ tonsillar cells was evaluated using flow cytometry.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 5.01 (San Diego, CA). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and n equals the number of independent donors. A P-value of ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical differences between paired data were determined by paired t-test (for two sets of data) or one-way repeated measures analysis of variance together with Dunnett's post test (for more than two sets of paired data).

Results

Expression of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar tissue

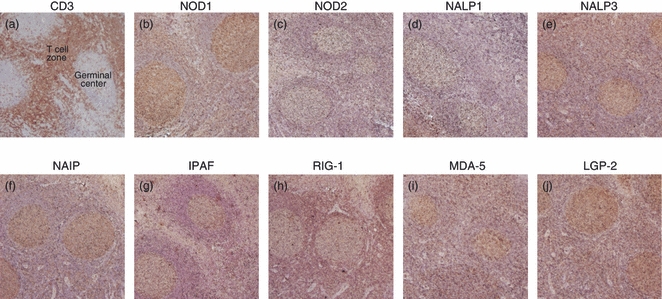

The palatine tonsils are constantly exposed to inhaled bacteria and viruses.15 Within these secondary lymphoid organs, innate immunity induces adaptive immune responses involving T lymphocytes.16 Immunohistochemical staining of tonsillar tissue showed that CD3+ cells were residing mainly in the T-cell areas adjacent to the germinal centres and characterization of NLR and RLR proteins revealed intense positive staining for NOD1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 in the T-cell zones (Fig. 1). A weak, but still positive staining was found for NOD2 and NALP1 whereas no immunostaining was found for the negative controls (data not shown), indicating the presence of NLRs and RLRs in T lymphocytes.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of tonsillar tissue. Tonsillar tissue slides were incubated with antibodies against (a) CD3, (b) nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1), (c) NOD2, (d) NACHT domain- leucine-rich repeat and pyrine domains containing proteins (NALP1), (e) NALP3, (f) neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein (NAIP), (g) ICE protease activating factor (IPAF), (h) retinoic acid inducible gene-1 (RIG-1), (i) melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 (MDA-5) and (j) laboratory of genetics and physiology 2(LGP-2), and visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (brown). N-series universal negative control reagent or antibody diluents were used as negative controls. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin (blue) and analysed using microscopy; 40× magnification. Results show one representative out of four independent donors.

Expression profiles of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar T cells

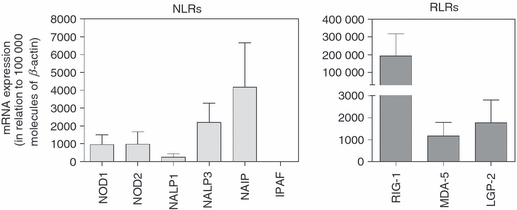

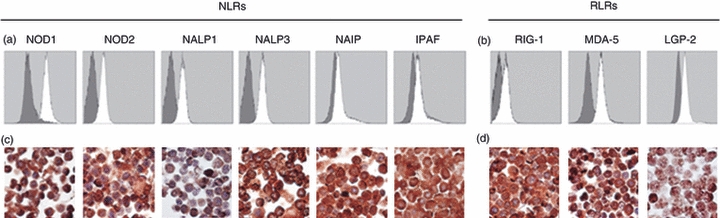

After establishing expression in the T-cell areas, we isolated CD3+ T cells from tonsils and investigated mRNA transcripts of NOD1, NOD2, NALP1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 using real-time RT-PCR. The cells demonstrated a broad range of NLRs along with a generally higher expression of the RLRs (Fig. 2). To further confirm the expression profiles of these receptors in T cells, flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry were carried out. In line with the immunostaining of tonsillar tissue and mRNA data, all receptors were detected in T cells using flow cytometry (Fig. 3a,b), although the expression of NAIP and IPAF was fairly weak. Immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against NOD1, NOD2, NALP1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 (Fig. 3c,d) confirmed the protein expression profiles found using flow cytometry.

Figure 2.

Messenger RNA profiles of nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD) -like receptors (NLRs) and retinoic acid inducible gene (RIG) -like receptors (RLRs) in purified lymphoid T cells. The mRNA expression of NOD1, NOD2, NACHT domain- leucine-rich repeat and pyrine domains containing proteins (NALP1), NALP3, neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein (NAIP), ICE protease activating factor (IPAF), RIG-1, melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 (MDA-5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2(LGP-2) was analysed using real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented in relation to the housekeeping gene β-actin as 2−ΔCt × 100 000 (n = 6).

Figure 3.

Protein expression of nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD) -like receptors (NLRs) and retinoic acid inducible gene (RIG) -like receptors (RLRs) in T cells. (a) Freshly isolated cells were intracellularly stained with antibodies against NOD1, NOD2, NACHT domain- leucine-rich repeat and pyrine domains containing proteins (NALP1), NALP3, neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein (NAIP), ICE protease activating factor (IPAF), (b) RIG-1, melanoma differentiation associated protein 5 (MDA-5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2(LGP-2) open histograms) and protein expression was determined by flow cytometry analysis. Appropriate isotype controls (grey histograms) were used to detect unspecific background staining. Immunohistochemical staining of (c) NLR and (d) RLR proteins [all visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (brown)] in purified tonsillar T cells. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin (blue) and analysed using microscopy at 1000× magnification. Results show one representative out of four independent donors.

Also, the protein expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was compared by depicting the NLR and RLR expression found by flow cytometry as relative mean fluorescence intensity (rMRI = NLR antibody/isotype control). The expression of NOD1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 was found to be significantly lower in cytotoxic T cells than in T helper cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Differential protein levels in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The expression of nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) and retinoic acid inducible gene-like receptors (RLRs) in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells assessed by flow cytometry was calculated as relative mean fluorescence intensity (rMRI = NLR antibody/isotype control). Data (n = 4) are presented as mean ± SEM and *P≤ 0·05, **P≤ 0·01.

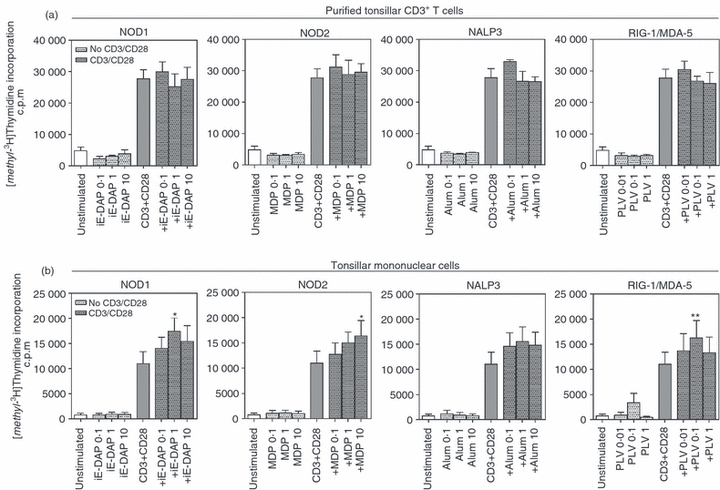

iE-DAP, MDP and Poly(I:C)LyoVec induce T-cell proliferation

Several recent studies have suggested a role of NLRs and RLRs in shaping adaptive immunity1,9,17 but there are no studies demonstrating activation of human T cells via the NLR or RLR system. As there are presently only ligands available for NOD1 (iE-DAP), NOD2 (MDP), NALP3 (Alum) and RIG-1/MDA-5 [Poly(I:C)/LyoVec], functional analysis is clearly restricted.

Freshly isolated tonsillar CD3+ T cells were stimulated with available ligands in the absence or presence of activating antibodies against CD3 and CD28 followed by analysis of the proliferative response after 72 hr. The concentrations of αCD3 and αCD28 along with the time-point for evaluation of proliferation were chosen based on kinetic studies (data not shown). The effect on proliferation was very low and no increase was seen upon stimulation. However, when signals via CD3 and CD28 were provided, a profound induction in proliferation was seen, but the proliferative response was not further enhanced by the NLR or RLR ligands (Fig. 5a). Instead, tonsillar mononuclear cells (Table 1) were used to create a milieu more similar to the biological system in which T cells and antigen-presenting cells interact. Also in these mixed cultures, the proliferation was unaffected by the ligands alone. However, stimulation with αCD3 and αCD28 clearly induced the proliferative response, and stimulation with iE-DAP, MDP and Poly(I:C)/LyoVec in combination with CD3/CD28 engagement resulted in a synergistic increase of proliferation (Fig. 5b). A trend towards an enhanced proliferative response was seen for Alum although it did not reach statistical significance (P = 0·28). Additionally, to ensure the specificity of iE-DAP and MDP, the cells were incubated with iE-Lys and the inactive D-D isomer of MDP at concentrations equivalent to those used for iE-DAP and MDP. These control ligands did not affect the proliferative response (data not shown). In all experiments, PMA and ionomycin were used as a positive control to guarantee the assay functionality (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Stimulation of nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-like receptors and retinoic acid inducible gene-like receptors induces T-cell proliferation. Freshly isolated (a) CD3+ tonsillar T cells (n = 4) and (b) tonsillar mononuclear cells (n = 10) were cultured in the absence or presence of γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), muramyl dipeptide (MDP), aluminium hydroxide (all 0·1–10 μg/ml), Poly(I:C)LyoVec (0·01–1 μg/ml) with or without αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml). After 72 hr, proliferation was quantified using thymidine incorporation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and *P≤ 0·05, **P≤ 0·01.

Table 1.

Cellular composition of tonsillar mononuclear cells

| CD3+ T cells | CD19+ B cells | CD14+ monocytes | BDCA2+ dendritic cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Positive cells | 29·0 ± 3·3 | 71·3 ± 2·0 | 7·1 ± 0·6 | 2·8 ± 0·6 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

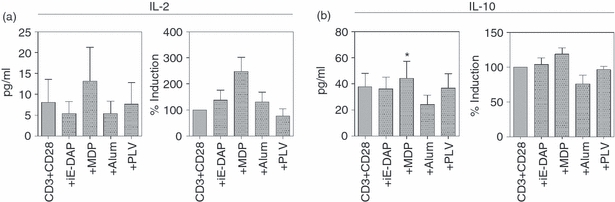

iE-DAP and MDP promote cytokine secretion

To verify the enhanced thymidine incorporation seen after stimulation with the ligands in the presence of TCR-triggering, proliferation in the form of IL-2 production was evaluated. It was found that the levels of IL-2 generally were low, and under the detection limit in four out of eight donors. However, in the remaining donors an induction was seen upon stimulation (Fig. 6a). Additionally, secretion of IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ was explored. Stimulation via NOD1 and NOD2 augmented the TCR-induced release of IL-10 (Fig. 6b), whereas the levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ were under the detection level of the assays (data not shown). Because of large variations in cytokine levels between different donors, the data were also normalized and presented as % induction compared with cells only stimulated with activating antibodies against CD3 and CD28.

Figure 6.

Stimulation of the nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domains NOD1 and NOD2 stimulation promotes cytokine secretion. Freshly isolated tonsillar mononuclear cells (n = 8) were cultured (1 × 106 cells/ml) with γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), muramyl dipeptide (MDP), aluminium hydroxide (Alum) (all 10 μg/ml) or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (1 μg/ml) in the presence of αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml). After 72 hr, secretion of (a) interleukin-2 (IL-2) and (b) IL-10 was measured by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and *P≤ 0·05.

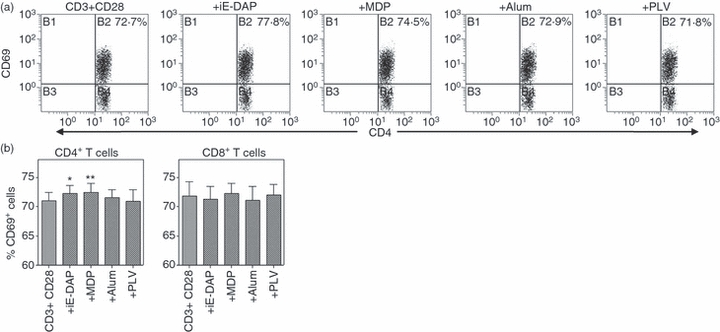

iE-DAP and MDP regulate expression of CD69

To further explore the nature of the NLR-induced and RLR-induced activation of T cells, regulation of the early activation marker CD69 was examined after 24 hr of stimulation of tonsillar mononuclear cells (Fig. 7). It was found that iE-DAP and MDP caused an up-regulated expression of CD69 in CD4+ T cells, whereas no effects were seen in CD8+ cells or after cultivation with Alum or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec.

Figure 7.

The nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domains NOD1 and NOD2 regulate expression of CD69. Freshly isolated tonsillar mononuclear cells (n = 6) cells were cultured (1 × 106 cells/ml) with γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), muramyl dipeptide (MDP), aluminium hydroxide (Alum) (all 10 μg/ml) or Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (1 μg/ml) in the presence of αCD3 (0·5 μg/ml) and αCD28 (1 μg/ml). After 24 hr, expression of CD69 in (a) CD4+ and (b) CD8+ T cells was analysed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the percentage of positive cells and depicted as mean ± SEM and *P≤ 0·05, **P≤ 0·01.

Discussion

The roles of NLRs and RLRs in various cell types and disorders have been extensively studied in several recent papers and expression of functional NLRs has been demonstrated in both non-immune cells and immune cells. Many studies have focused on cells of the innate immune system including monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells18,19 and we have shown that human neutrophils express NOD2 and NALP3 and that stimulation with the cognate ligands promotes activation.14 So far, information regarding NLRs and RLRs in human adaptive immune cells is very restricted. Lech et al. have provided evidence for mRNA and functionality of NLRs and RLRs in peripheral T cells20 and a recent study from our department shows functional relevance of NLRs in human B lymphocytes.21 However, information regarding these receptors in tonsil-derived T cells has until now been lacking.

In the present study we demonstrate, for the first time, that human tonsillar T cells display a broad repertoire of NLRs and RLRs including NOD1, NOD2, NALP1, NALP3, NAIP, IPAF, RIG-1, MDA-5 and LGP-2. Also, a differentiated expression of NOD1, MDA-5 and LGP-2 was seen in T helper cells and cytotoxic T cells, which is most probably a reflection of differences in effector functions as previously reported for TLRs in CD4+ and CD8+.3,22 We also show that mRNA levels do not equal the corresponding receptor expression at protein level and this could be related to differences in transcriptional control and protein consumption23,24 as previously demonstrated in human leucocytes.6,25 In contrast to a study by Kolly et al. reporting lack of the NALP3 protein in T cells derived from synovium of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,26 we found a clear expression of NALP3 in tonsillar T cells. However, it is well-recognized that cells from different compartments are phenotypically different and could have divergent expression profiles of PRRs.4,21,27 Moreover, because of the high antigen load within the tonsils, a microbe-induced regulation in NALP3 expression might have occurred as previously described for TLRs.4,22

After having characterized the expression profiles of NLRs and RLRs, the functional importance of the receptors was investigated by means of thymidine incorporation, cytokine secretion and regulation of the activation marker CD69. However, synthetic ligands are only available for a small number of the NLRs and RLRs, and therefore evaluation of functional activity was restricted to NOD1, NOD2, NALP3 and RIG-1/MDA-5 using the agonists iE-DAP, MDP, Alum and Poly(I:C)/LyoVec, respectively. None of the ligands alone were found to exert effects on freshly isolated CD3+ T cells or tonsillar mononuclear cells. Neither were the ligands able to induce proliferation of purified T cells in combination with αCD3 and αCD28. However, in tonsillar mononuclear cells, prominent effects were seen for iE-DAP (∼ 1·6-fold induction compared with CD3 and CD28 stimulation), MDP (∼ 1·5-fold) and Poly(I:C)/LyoVec (∼ 1·5-fold). The lack of responsiveness in purified T cells could be linked to the absence of antigen-presenting cells in these cultures. In the mixed cultures, on the other hand, the setting was more similar to the biological system where the T cells can directly interact with dendritic cells, monocytes and B cells. Hence, the activation via the NLRs and RLRs might be dependent on soluble mediators released from surrounding cells and by cell–cell contact as described in a recent study by Richardt-Pargmann et al. in which monocytes were found to suppress T-cell proliferation upon TLR8 activation.28

The MDP, and to some extent iE-DAP, were also able to induce secretion of IL-2, which is known to play a key role in promoting the proliferation of antigen-specific T cells,29 hence strengthening the finding of the enhanced thymidine incorporation. Additionally, these ligands appear to augment the TCR-induced secretion of IL-10 in tonsillar mononuclear cells and cause an up-regulation of CD69 exclusively in CD4+ tonsillar T cells. The lack of responsiveness in cytotoxic T cells might be linked not only to the generally higher protein expression of NLRs and RLRs found in T helper cells but also to the different roles of these subsets upon infection. CD69 is an early activation marker30 that has been reported to increase the ability of cells to interact with the surroundings.31 Although the interaction between CD4+ cells and other cells is crucial in the regulation of cell-mediated immune responses towards bacterial infections,32 CD8+ cells are mainly involved in defence against viral infections. Hence, this could be an explanation as to why only CD4+ cells appear to be responsive to the bacteria-derived cell wall components iE-DAP and MDP.

Even though the tonsillar T-cell responses induced by the NOD ligands are of fairly low magnitude, the recognition of iE-DAP and MDP is highly specific. This is in line with the finding that the cells were completely unresponsive to their corresponding control ligands. The minimal motif recognized by NOD1 is d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid and when diaminopimelic acid is replaced by lysine (giving d-glutamyl-lysine; iE-Lys) the ability to stimulate the NOD1 receptor is eliminated. NOD2 functions as a sensor of muramyl dipeptide11 and other analogues than the l-d isomer is not recognized by the receptor. Also, by using highly pure ligand preparations (endotoxin levels < 0·125 EU/ml) the possible contribution of contaminants and off-target effects was reduced.

As NALP3 was expressed at similar levels as NOD1, NOD2 and RIG-1/MDA-5, it seemed likely that its corresponding ligand also would promote proliferation of tonsillar T cells. However, no effects were found for the NALP3 ligand Alum either on proliferation, secretion of cytokines or up-regulation of CD69, confirming that expression profiles do not always equal functional activity. Also, it should be noted that iE-DAP, MDP and Poly(I:C)/LyoVec are all specific ligands whereas it is still unclear whether Alum mediates its effect solely via NALP3.33,34 The tentative unspecific activity of Alum might be related to its receptor-activating failure. Additionally, although Poly(I:C)/LyoVec was able to induce proliferation, it did not affect the other examined T-cell functions, which is most probably the result of the different mechanisms behind the responses.

Altogether, the results presented in this study indicate that tonsillar T cells stimulated with NLR agonists acquire an activated phenotype, suggesting these receptors to be of importance in T-cell activation. In support of this, Lech et al. have in a recent study reported major effects on RANTES and IL-1β secretion upon stimulation of purified human and murine peripheral T cells with NLR ligands.20 However, the differences in the magnitude in the responses could be explained by species-related differences between man and mice as well as by functional diversity of cells from different origin.

Functional activities of NLRs and RLRs in T cells are an interesting observation because adaptive immune cells traditionally are not thought to be involved in the initial responses against invading pathogens. Previous studies on TLRs have shown expression and function in T cells35 but it is still a matter of controversy whether the reported effects are direct or mediated via antigen-presenting cells.36,37 As for some of the TLRs, the corresponding ligands alone did not directly activate tonsillar T cells, instead effects were seen when stimulatory signals via CD3 and CD28 were provided.

Since the discovery of PPRs, and most prominently the TLRs, the understanding of innate immune recognition has advanced rapidly. NOD1 and NOD2 are mainly involved in the detection of cytoplasmic bacterial peptidoglycan38 whereas both RIG-1 and MDA-5 have been demonstrated to respond to cytosolic double-stranded viral RNA.39,40 During infection, invading pathogens will most likely engage several different PRRs simultaneously. Their different cellular locations, with TLRs on the cell surface and within the endosomes41 and the NLRs and RLRs screening the cytoplasmic compartment,9 might be a way to ensure an effective clearance of infection. Also, it has been suggested that NLRs and RLRs act as backup systems for bacteria and viruses that have been able to escape the initial recognition of the TLRs or have escaped from the endosomal compartments.9 Therefore, it is most likely the combined effects of these receptors that are of biological importance and not the effects induced by the individual receptors.

The role of cytosolic PRRs is just beginning to emerge and in the present study we demonstrate for the first time distinct expression and functionality of NLRs and RLRs in human tonsillar T cells, which suggests a role for these receptor families in T-cell activation. Additionally, our data complements previous studies regarding the importance of innate immune receptors also in the adaptive branch of the immune system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Ingegerd Larsson for coordinating the collection of tonsils and for helpful assistance during the course of this study. We would also like to acknowledge support from the Swedish Medical Research Council and the Swedish Heart-Lung foundation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Alum

aluminium hydroxide

- iE-DAP

γ-d-glutamyl-meso diaminopimelic acid

- iE-Lys

d-glutamyl-lysine

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- IPAF

ICE protease activating factor

- LGP-2

laboratory of genetics and physiology-2

- MDA-5

melanoma differentiation associated gene-5

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- NAIP

neuronal apoptosis inhibitor protein

- NALP

NACHT domain-, leucine rich repeat- and pyrine domains-containing proteins

- NLR

NOD-like receptor

- NOD

nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain

- Poly(I:C)/LyoVec

Polyinosine-polycytidylic acid LyoVec

- PRR

pattern-recognition receptor

- RIG

retinoic acid-inducible gene

- RLR

RIG-like receptor

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

References

- 1.Williams A, Flavell RA, Eisenbarth SC. The role of NOD-like receptors in shaping adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukata M, Vamadevan AS, Abreu MT. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and Nod-like receptors (NLRs) in inflammatory disorders. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:242–53. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansson A, Adner M, Cardell LO. Toll-like receptors in cellular subsets of human tonsil T cells: altered expression during recurrent tonsillitis. Respir Res. 2006;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansson A, Adner M, Hockerfelt U, Cardell LO. A distinct Toll-like receptor repertoire in human tonsillar B cells, directly activated by PamCSK, R-837 and CpG-2006 stimulation. Immunology. 2006;118:539–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438:364–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akashi-Takamura S, Miyake K. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and immune disorders. J Infect Chemother. 2006;12:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s10156-006-0477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Misch EA, Hawn TR. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to human disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:347–60. doi: 10.1042/CS20070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:221–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol. 2009;21:317–37. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchi L, Warner N, Viani K, Nunez G. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:106–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogefors J, Rydberg C, Uddman R, Fransson M, Mansson A, Benson M, Adner M, Cardell LO. Nod1, Nod2 and Nalp3 receptors, new potential targets in treatment of allergic rhinitis? Allergy. 2010;65:1222–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins C, Gale M., Jr Recognition of viruses by cytoplasmic sensors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekman AK, Cardell LO. The expression and function of Nod-like receptors in neutrophils. Immunology. 2010;130:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nave H, Gebert A, Pabst R. Morphology and immunology of the human palatine tonsil. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2001;204:367–73. doi: 10.1007/s004290100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quiding-Jarbrink M, Granstrom G, Nordstrom I, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Induction of compartmentalized B-cell responses in human tonsils. Infect Immun. 1995;63:853–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.853-857.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salek-Ardakani S, Croft M. T cells need Nod too? Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1231–3. doi: 10.1038/ni1209-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ting JP, Davis BK. CATERPILLER: a novel gene family important in immunity, cell death, and diseases. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:387–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kufer TA, Sansonetti PJ. Sensing of bacteria: NOD a lonely job. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lech M, Avila-Ferrufino A, Skuginna V, Susanti HE, Anders HJ. Quantitative expression of RIG-like helicase, NOD-like receptor and inflammasome-related mRNAs in humans and mice. Int Immunol. 2010;22:717–28. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petterson T, Månsson A, Riesbeck K, Cardell L-O. Effects of NOD-like receptors in human B lymphocytes and crosstalk between NOD1/NOD2 and Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:177–87. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarember KA, Godowski PJ. Tissue expression of human Toll-like receptors and differential regulation of Toll-like receptor mRNAs in leukocytes in response to microbes, their products, and cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168:554–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodson RE, Shapiro DJ. Regulation of pathways of mRNA destabilization and stabilization. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2002;72:129–64. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(02)72069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rippe RA, Stefanovic B. Methods for assessing the molecular mechanisms controlling gene regulation. Methods Mol Med. 2005;117:141–60. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-940-0:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagase H, Okugawa S, Ota Y, et al. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors in eosinophils: activation by Toll-like receptor 7 ligand. J Immunol. 2003;171:3977–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolly L, Busso N, Palmer G, Talabot-Ayer D, Chobaz V, So A. Expression and function of the NALP3 inflammasome in rheumatoid synovium. Immunology. 2010;129:178–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansson A, Fransson M, Adner M, Benson M, Uddman R, Bjornsson S, Cardell LO. TLR3 in human eosinophils: functional effects and decreased expression during allergic rhinitis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151:118–28. doi: 10.1159/000236001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardt-Pargmann D, Wechsler M, Krieg A, Vollmer J, Jurk M. Positive T cell co-stimulation by TLR7/8 ligands is dependent on the cellular environment. Immunobiology. 2011;216:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoyer KK, Dooms H, Barron L, Abbas AK. Interleukin-2 in the development and control of inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sancho D, Gomez M, Sanchez-Madrid F. CD69 is an immunoregulatory molecule induced following activation. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:136–40. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dallaire MJ, Ferland C, Page N, Lavigne S, Davoine F, Laviolette M. Endothelial cells modulate eosinophil surface markers and mediator release. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:918–24. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00102002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufmann SH, Schaible UE. Antigen presentation and recognition in bacterial infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, et al. Cutting edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O'Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabelitz D. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors in T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendigs S, Salzer U, Lipford GB, Wagner H, Heeg K. CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides co-stimulate primary T cells in the absence of antigen-presenting cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1209–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199904)29:04<1209::AID-IMMU1209>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kranzer K, Bauer M, Lipford GB, Heeg K, Wagner H, Lang R. CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides enhance T-cell receptor-triggered interferon-gamma production and up-regulation of CD69 via induction of antigen-presenting cell-derived interferon type I and interleukin-12. Immunology. 2000;99:170–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritz JH, Ferrero RL, Philpott DJ, Girardin SE. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1250–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gitlin L, Barchet W, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Beutler B, Flavell RA, Diamond MS, Colonna M. Essential role of mda-5 in type I IFN responses to polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8459–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603082103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, et al. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity. 2005;23:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor and RIG-I-like receptor signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]