Abstract

Frequencies of natural killer (NK) cells from patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) or small cell lung cancer (SCLC) did not differ from healthy controls. A higher proportion of NK cells from NSCLC patients expressed the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) CD158b than in controls (P = 0·0004), in the presence or absence of its ligand, HLA-C1. A similar result was obtained for CD158e in the presence of its ligand HLA-Bw4 in NSCLC patients (P = 0·003); this was entirely attributable to the Bw4I group of alleles in the presence of which a fivefold higher percentage of CD158e+ NK cells was found in NSCLC patients than controls. Proportions of CD158b+ NK cells declined with advancing disease in NSCLC patients. Expression of NKp46, CD25 and perforin A, and production of interferon-γ following stimulation with interleukin-12 and interleukin-18, were all significantly lower in NK cells from NSCLC patients than in controls. Both NK cell cytotoxicity and granzyme B expression were also reduced in lung cancer patients. Increased inhibitory KIR expression would decrease NK cell cytotoxic function against tumour cells retaining class I HLA expression. Furthermore, the reduced ability to produce interferon-γ would restrict the ability of NK cells to stimulate T-cell responses in patients with lung cancer.

Keywords: cytotoxicity, interferon-γ, killer immunoglobulin-like receptors, lung cancer, natural killer cells

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells provide a first line of defence against viral infections and malignantly transformed cells. They comprise about 10% of lymphocytes in human peripheral blood and are distinguished from other lymphocytes by expression of CD56 in the absence of CD3. The two predominant subsets, CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells, are mainly responsible for cytotoxicity and cytokine production, respectively.1

Natural killer cells express a range of receptors from several different families, which regulate the killing activity of NK cells, one of which is the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) family. The KIRs are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily of receptors and are encoded on chromosome 19q13.4. The KIR gene cluster comprises up to 17 highly homologous and closely linked genes and pseudogenes. The KIRs can be classified into two different groups: first, the inhibitory group is characterized by a long (L) intracytoplasmic tail and two or three extracellular immunoglobulin domains. Second, the activating group has two or three extracellular immunoglobulin domains and a short (S) intracytoplasmic tail.2 The KIR activating receptors function via the adapter molecule DAP12 whereas KIR inhibitory receptors inhibit NK cell function via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs.3,4 Ligand specificities for only four of the inhibitory KIRs have been clearly defined: KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL3 for the HLA-CAsn80 (C1) group of alleles, KIR2DL1 for the HLA-CLys80 (C2) group and KIR3DL1 for the Bw4 group of HLA-B (and some A) alleles.5 Specificities of the remaining inhibitory and activatory receptors are less well characterized.

Two main groups of KIR haplotypes that differ in numbers and types of KIR genes have been defined in human populations. Group A haplotypes encode several inhibitory KIRs but lack all activating KIR genes except KIR2DL4, whereas group B haplotypes encode several inhibitory and activating KIRs.5 Haplotype AA homozygotes would therefore lack most activating receptors while AB or BB (BX) subjects would have several. Cells that express class I HLA molecules are protected from NK cell killing, whereas cells that down-regulate or lose class I HLA molecules are susceptible to NK cell killing. Therefore, KIR inhibitory receptors block NK cell killing activity by binding class I HLA molecules and delivering inhibitory signals. However, lack of expression of class I HLA molecules leads to activation of NK cell killing activity through delivery of activating signals.6

Lung cancer can be subdivided into two main forms, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC); the latter is less common, representing around 15% of lung cancers, and is thought to be of neuroendocrine origin.7 Although originally thought to be poorly immunogenic, there have been recent indications that lung cancer may be amenable to immunotherapy.8,9 Regarding the participation of NK cells in immunity to lung cancer, in mouse models, stimulation of NK cell function enhanced migration to the lung and protected against lung cancer metastasis10 and NK cell depletion enhanced lung cancer metastasis.11 More indirectly, cigarette smoking has been found to decrease NK cell activity12 and, in a mouse model, to decrease NK-cell-mediated tumour surveillance, which could be overcome by NK cell stimulation.13 The NK cell populations infiltrating NSCLC are predominantly CD16− CD56bright,14 which is the minor subset in peripheral blood, responsible for cytokine production rather than cytotoxic function.1 The aims of this study were to investigate the KIR phenotype and function of NK cells in the peripheral blood of lung cancer patients to determine whether NK cells are functionally impaired in comparison with healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

Blood samples were obtained following informed consent from patients with lung cancer attending clinics at St Helens & Knowsley NHS Trust, Liverpool Cardiothoracic Centre NHS Trust and Aintree Hospital NHS Trust, Merseyside, UK. These comprised 67 patients with NSCLC and 30 with SCLC. Patients were either newly diagnosed or were sampled at follow-up after a course of treatment. No samples were taken within 2 months after chemotherapy. Sixty-nine normal healthy volunteers from Merseyside and of the same ethnic background (predominantly Caucasian) were used as controls. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Cheshire and Liverpool NHS Research Ethics Committees.

Cell preparation and DNA extraction

Blood was taken into preservative-free heparin (30 units/ml of blood) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. Blood was gently layered onto an equal volume of Ficoll-Paque™ Plus (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and centrifuged at 400 g for 20 min at room temperature. The PBMC were harvested from the interface and washed twice with phosphate-buffered isotonic saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min. DNA was prepared from approximately 107 PBMC using a DNeasy blood & tissue kit (product number: 69504; Qiagen, Crawley, Sussex, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol. K562 and HeLa cell lines were obtained from cryopreserved stocks from the Department of Haematology, University of Liverpool in 2008. Cells were maintained by twice weekly passage in culture medium (RPMI-1640 + 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum + 2 mm glutamine + antibiotics) and checked morphologically at weekly intervals.

Reagents

Monoclonal antibodies used in the study were: anti-human phycoerythrin-Cy5-conjugated CD3 (CD3-PE-Cy5); mouse IgG1-PE isotype control (both Dako, Ely, UK); anti-human CD56-FITC; anti-human CD158b-PE (anti-KIR2DL2/DL3; also recognizes CD158j, KIR2DS2); anti-perforin A-PE; mouse IgG2b-FITC isotype control (BD Pharmingen, Oxford, UK); anti-human CD158a-PE (anti-KIR2DL1; also recognizes CD158h, KIR2DS1); anti-human CD158e-PE (anti-KIR3DL1); anti-human interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-PE (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK).

Phenotypic analysis

Surface phenotyping was carried out using three-colour immunofluorescence staining; 5 × 105 fresh PBMC were stained with appropriate mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies conjugated with FITC, PE and PE-Cy5 for 30 min in the dark at 4°. The cells were washed twice with cold PBS, resuspended in 0·5 ml of PBS and analysed using an EPICS XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter, Luton, UK), gated for lymphocytes on the basis of forward and side scatter. Negative controls were applied using relevant labelled mouse IgG isotype controls and fluorescence thresholds set so that < 1% of lymphocytes showed non-specific antibody binding.

Intracellular staining

For measurement of intracellular IFN-γ, PBMC suspended in culture medium at 106/ml were stimulated for 24 hr with 10 ng/ml interleukin-12 (IL-12) and 100 ng/ml IL-18 (Peprotech, London, UK). Two hours before analysis, brefeldin A was added at 10 μg/ml and cells were washed and labelled with anti-CD3-PE-Cy5 and anti-CD56-FITC as above. Cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and washed twice with saponin buffer (BD Pharmingen), resuspended in 100 μl saponin buffer and incubated with anti-human IFN-γ-PE antibody (Beckman Coulter) for 40 min at 4°. After a final wash in saponin buffer, cells were analysed on the flow cytometer, using a different lymphocyte gate from that used for fresh cells because of the alteration in scatter properties following cell fixation. Intracellular staining for perforin A was carried out in the same manner on fresh cells using anti-human perforin A-PE antibody but without cytokine stimulation or brefeldin A treatment. Appropriate isotype control reagents were used in all experiments.

Cytokine production by purified NK cells

The NK cell purification was carried out using an NK cell negative isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bisley, Surrey, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. From a starting population of 107 PBMC, populations of NK cells which were 92–95% CD56+ cells with < 0·1% T-cell contamination were routinely obtained. Purified NK cells at a concentration of 106/ml were then stimulated with K562 or HeLa cells at a ratio of 1 : 1 overnight. Supernatants were stored at −70° and then assayed for: IL-2, IL-4, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-17, IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 using the human cytokine/chemokine MILLIPLEX™ MAP multiplex assay kit (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Controls were PBMC, K562 or HeLa cells incubated alone. Cytokine content was measured in duplicate samples in comparison with standards using a Liquichip 100 workstation (Qiagen Ltd, West Sussex, UK) with liquichip IS 2.3 software, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytotoxicity assay

K562 target cells were maintained in exponential growth in culture medium by subculturing twice weekly. They were labelled with Na251CrO4 (Perkin Elmer, Cambridge, UK) for 1 hr at 37° and washed twice before use. Then, 104 51Cr-labelled target cells in culture medium were added at 100 μl/well to a 96-well U-bottomed plate. The PBMC effector cells in culture medium were added in triplicate at effector : target ratios of 1 : 1, 10 : 1 and 20 : 1 in 100 μl medium. Spontaneous chromium release was measured by adding 100 μl culture medium alone to target cells and maximum chromium release was measured by adding 100 μl 2% Triton X-100. The plate was centrifuged at 100 g for 3 min and incubated for 4 hr at 37°. Then, 100-μl aliquots were removed from each well and added to 4 ml scintillation fluid (Meridian, Epsom, Surrey, UK) and counted using a Packard 2100 counter. The mean per cent specific cytotoxicity was calculated from the equation:

Real-time PCR

RNA was prepared by adding 1 ml Trizol (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and 200 μl chloroform to 106 PBMC and incubating for 5 min. After centrifuging at 13 000 g for 10 min at 4°, RNA was precipitated from the upper aqueous phase by adding 600 μl isopropanol and leaving overnight at −20°. After centrifugation and washing with ethanol, the RNA was resuspended in 15 μl DNAse- and RNAse-free water. The mRNA was reverse transcribed at 42° for 1 hr and the resulting cDNA was subjected to PCR in triplicate using a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK).

HLA typing

DNA for HLA typing was either isolated directly from patients’ blood or from PBMC using the Qiagen Q1Aamp DNA Blood Mini kit, which uses a Mini Spin column for purification of the DNA after whole blood digestion with protease K. HLA class I typing (A, B and C loci) was performed using PCR-sequence specific oligonucleotide probes from Dynal RELI HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C kits (Dynal Biotech Ltd, Wirral, UK). Controls and patients were classified as to whether they were positive for C1 or C2 groups of HLA-C or both, and HLA-Bw4 (Bw4T or Bw4I), -Bw6 or both.

Statistical analysis

Graphic representation was performed using graphpad prism software (Pugh, Aberystwyth, UK). The differences between healthy subjects and patients with lung cancer (NSCLC and SCLC) were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U-test, where data were clearly not normally distributed, or one-way analysis of variance.

Results

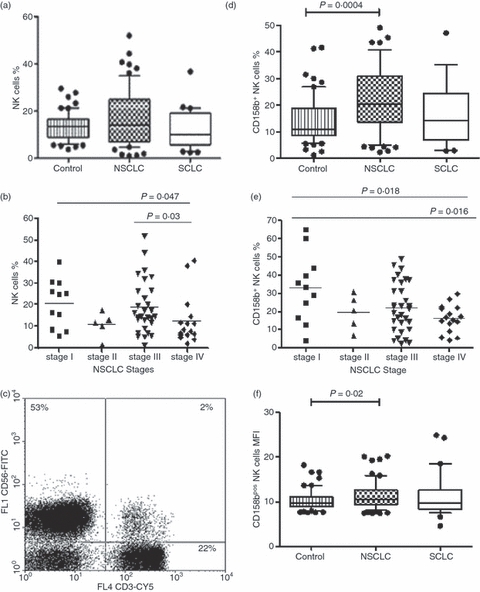

Unaltered proportions of NK cells in patients with lung cancer

The proportion of lymphocytes that were CD3− CD56+ (NK cells) was measured in 67 patients with NSCLC and 30 patients with SCLC compared with healthy controls (n = 69). In lung cancer patients, there were no significant differences in the median proportions of NK cells for patients with NSCLC and SCLC compared with healthy subjects (Fig. 1a). However, the patients with NSCLC showed a very wide range of percentages of NK cells, in one patient 53% of lymphocytes, mainly CD56dim cells, being NK cells (Fig. 1c), while others had a very small percentage of NK cells (approximately 1·5%; Fig. 1a). The mean age of patients with NSCLC was 66 ± 8·6 years and for patients with SCLC it was 67 ± 9·8 years, which was higher than the mean age of the healthy controls used. However, there were no significant differences in phenotypic or functional data between different age groups of healthy controls up to the age of 68 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

(a) The percentage of natural killer (NK) cells in patients with lung cancer [non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); n = 67 and small cell lung cancer (SCLC); n = 30] and healthy controls (n = 69). Medians, interquartile ranges and 95% CIs are shown, with outlying points shown individually. (b) The percentage of NK cells in patients with NSCLC according to disease stage; there was a significant decrease overall (P = 0.047, one-way analysis of variance, and particularly between stages III and IV, P = 0.03). (c) Flow cytometry data from a single patient with NSCLC illustrating an abnormally high percentage of NK cells (upper left quadrant, 53%) and low percentage of T cells (CD3+ CD56− and CD3+ CD56+; lower and upper right quadrant, 24%). (d) The percentage of NK cells expressing CD158b in healthy controls, and in patients with NSCLC and SCLC. A significantly higher percentage CD158bs cells in NSCLC than controls was found (P = 0.0004). (e) The percentage CD158b+ NK cells in patients with NSCLC according to disease stage: there was a significant decrease overall, P = 0.018, one-way analysis of variance, and between patients with stage I and IV disease, P = 0.016). (f) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for CD158b in CD158b+ NK cells from healthy controls and from patients with NSCLC and SCLC. Median levels were significantly higher in patients with NSCLC than controls (P = 0.02, Mann–Whitney U-test).

NK cell expression of KIR in lung cancer patients

Anti-CD158a, -b and -e antibodies were used to detect KIRs on the surface of NK cells in patients with lung cancer and healthy controls. The percentage of CD158a+ NK cells and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) were similar in controls and in patients with NSCLC and SCLC (data not shown). Unlike for CD158a, a significantly higher percentage of CD158b+ NK cells in NSCLC was observed compared with the controls (20·5% versus 11·05% respectively (P = 0·0004; Fig. 1d). Mean levels of expression of CD158b on the NK cell surface were also increased in NSCLC in relation to the control group (P = 0·002; Fig. 1f). Because different KIR haplotypes exist, the expression of CD158b was examined in two different genotypes (AA and BX, where X = A or B) in controls, NSCLC and SCLC groups. Patients with NSCLC with the haplotype BX had a higher median percentage of CD158b+ NK cells compared with healthy controls (22·3% versus 14·9%, P = 0·02, Mann–Whitney test). However, there were no significant differences in CD158b expression in AA haplotypes in NSCLC, SCLC or controls (data not shown).

The third KIR (CD158e) was found at higher mean levels in both lung cancer groups compared with healthy subjects. However, there was no statistically significant difference except the MFI of CD158e on NK cells between NSCLC and controls (P = 0·001; data not shown). CD158e expression within different haplotypes revealed that patients with NSCLC who had the AA haplotype showed a higher mean level of CD158e than controls (23·6 versus 12·1 arbitrary units; P = 0·01; data not shown). Patients with SCLC who had the BX haplotype had an MFI of 17 for CD158e compared with 11·2 in controls (P = 0·04; data not shown).

Frequencies of potentially functional KIR+ NK cells in lung cancer patients

KIR2DL2, 2DL3 and 2DS2 recognize HLA-C group 1 alleles: C*01, C*03, C*07 and C*08 while HLA-C2 alleles (C*02, C*04, C*05 and C*06) are bound by KIR2DL1 and 2DS1. However, because the HLA ligands and their KIR receptors are encoded on different chromosomes, it is possible to express a KIR with no corresponding expression of a relevant HLA class I ligand.15 Therefore, frequencies of KIR+ NK cells were measured in lung cancer patients and normal controls with or without the gene for the cognate ligand.

Neither the percentage of NK cells expressing CD158a in the presence of HLA-C2, nor the MFI for CD158a, differed significantly between patients with NSCLC and SCLC and controls (P> 0·05; data not shown). In contrast, in the absence of HLA-C2, the percentage of CD158a+ NK cells and the MFI of CD158a in SCLC was significantly lower than in controls (7·04% versus 12%; P = 0·03 and 7·8 versus 11·2 arbitrary units; P = 0·02, respectively; data not shown). However, patients with NSCLC showed no difference from healthy controls in the percentage of positive cells and MFI of CD158a in the absence of its ligand.

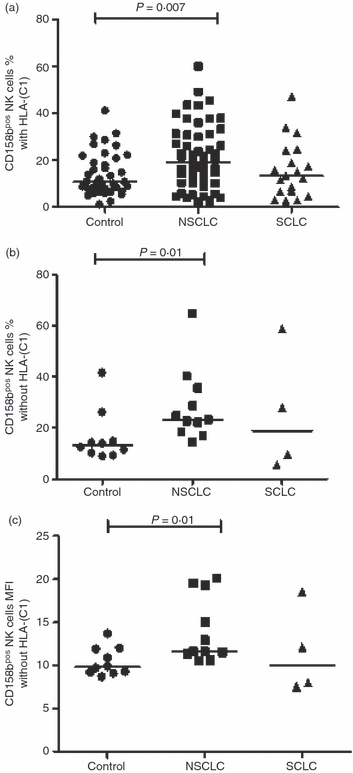

The proportions of NK cells expressing CD158b were apparently modulated in NSCLC and SCLC in the presence or absence of HLA-C1. In patients with NSCLC a median of 19·1% of NK cells were CD158b+ in combination with its ligand compared with 10·8% in healthy subjects (P = 0·007; Fig. 2a). Again the percentage of CD158b+ NK cells and the MFI in the absence of its ligand were greater than in controls (P = 0·01; Fig. 2b,c).

Figure 2.

The percentage of natural killer (NK) cells from controls and from patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) expressing CD158b; (a) in the presence of HLA-C1; (b) in the absence of HLA-C1; (c) mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD158b on NK cells in the absence of HLA-C1. The horizontal lines represent median values. Statistically significant differences compared with controls are shown.

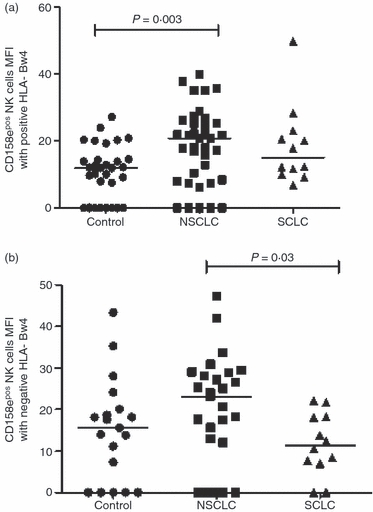

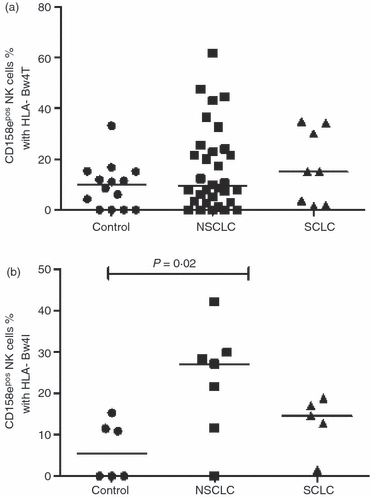

Two different groups of alleles of HLA-Bw4, Bw4T and Bw4I, designated by the amino acid threonine or isoleucine in position 80, can be bound by KIR3DL1, recognized by anti-CD158e antibodies. An individual can be homozygous for Bw4T or Bw4I or carry a single copy, heterozygous and carry both, or negative for both. Initially, frequencies of CD158e+ NK cells in the presence or absence of HLA-Bw4 were investigated, revealing no significant differences between healthy controls and patients with lung cancer (data not shown). However, the median MFI of CD158e on NK cells in the presence of its corresponding ligand (Bw4) in NSCLC was significantly higher than in healthy subjects (P = 0·003; Fig. 3a). In the case of subjects lacking the CD158e ligand, NSCLC patients also had a higher level of CD158e on the surface of NK cells in relation to normal controls (P = 0·03; Fig. 3b). Consideration of the allelic groups of Bw4 revealed that in NSCLC patients the increased percentage of CD158e+ NK cells compared with controls was attributable to the Bw4I group of alleles and not Bw4T (27·2% versus 5·4%, P = 0·02; Fig. 4b). In contrast, the differences between the groups in the percentage +ve NK cells or the MFI of CD158e in combination with Bw4T were not statistically significant (Fig. 4a; data not shown).

Figure 3.

The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of gated natural killer (NK) cells expressing CD158e (a) in the presence and (b) in the absence of HLA-Bw4. MFI for CD158e was higher in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than in controls in the presence of HLA-Bw4 (P = 0.003) and in NSCLC than small cell lung cancer (SCLC) in the absence of HLA-Bw4 (P = 0.03).

Figure 4.

Percentage of CD158e+ natural killer (NK) cells in the presence of different alleles of HLA-Bw4; (a) Bw4T %; (b) Bw4I. A significantly higher percentage of CD158e+ NK cells was found between non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients and controls in the presence of HLA-Bw4I (P = 0.02). SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

The distribution of KIR according to cancer stage

Sixty-three patients with NSCLC were classified into four different stages using established clinical criteria. A one-way analysis of variance test was used to examine the difference between all four groups and a Mann–Whitney U-test was used to determine differences between pairs of groups only. Stage IV patients had a significantly lower percentage of NK cells compared with the patients in stages I and III (Fig. 1b). The percentage of NK cells that expressed CD158b was significantly higher in early than late stage disease when analysed using a one way analysis of variance test (P = 0·018; Fig. 1e). When the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied, it was observed that the mean percentage of cells expressing CD158b was lower in stage IV compared with stage I (16·2% versus 33%, P = 0·016; Fig. 1e). In SCLC, there was a significantly lower proportion of NK cells in patients with extensive disease compared with those with limited disease (14·8 ± 8·3 versus 7·8 ± 5·2; P = 0·012, data not shown). However, there were no significant differences in the % KIR+ NK cells between patients with limited or extensive disease (data not shown).

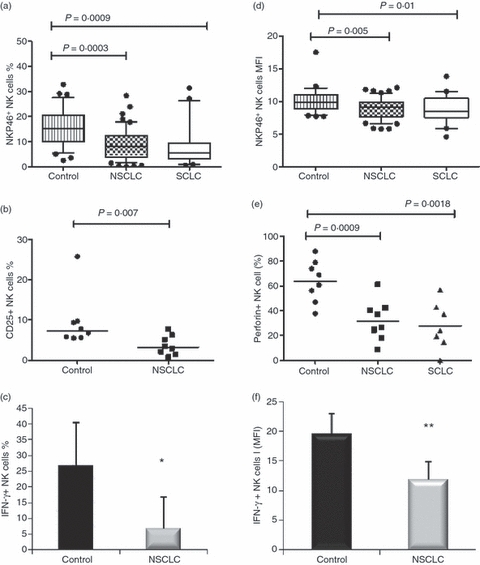

NK cell expression of activation markers and functional molecules in lung cancer

The proportion of NK cells expressing the natural cytotoxicity receptor (NCR) NKp46 was measured in patients with NSCLC and SCLC compared with normal controls. As shown in Fig. 5, both the absolute percentages of NK cells expressing NKp46 and the mean levels were significantly lower in both types of cancer compared with normal controls. In patients with NSCLC, the median percentage NKp46+ NK cells was lower in patients with stage IV disease than stage III (P = 0·041) and median levels of NKp46 per cells declined significantly with advancing stage (P = 0·036; data not shown). In a smaller sample of patients and controls (n = 8), patients with NSCLC were found to have significantly lower percentages of NK cells positive for cell surface CD25 and intracellular perforin A than normal controls (Fig. 5c; P = 0·007; Fig. 5d; P = 0·0009, respectively). When intracellular IFN-γ was examined following stimulation of PBMC with IL-12 and IL-18, both the percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells and median levels were highly significantly lower in patients with NSCLC than controls (Fig. 5e; P = 0·005; Fig. 5f; P = 0·0003, respectively). Natural killer cells from patients with SCLC also had a lower median percentage of intracellular perforin A+ NK cells than those from controls (Fig. 5d; P = 0·0018).

Figure 5.

Expression of activation and functional markers by natural killer (NK) cells in lung cancer; (a) percentage of NK cells expressing NKp46 and (b) mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; arbitrary units) of NKp46 expression. Medians, interquartile ranges and 95% CIs are shown, with outlying points shown individually. (c) percentage of NK cells expressing CD25; (d) median percentage of NK cells positive for perforin A in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and in normal controls. (e) Median percentage of interferon-γ-positive (IFN-γ+) NK cells and (f) MFI for IFN-γ (arbitrary units) in controls and patients with NSCLC ± SE (n = 8). *NSCLC significantly lower than controls, P = 0.005; **P = 0.0003.

Levels of mRNA for granzyme A and granzyme B were measured by real-time PCR in PBMC from patients with lung cancer and normal controls. The ratio of levels in controls, NSCLC and SCLC were 100 : 83·2 : 42·5 for granzyme A and 100 : 43·2 : 7·1 for granzyme B, in the latter case the difference between patients with SCLC and controls was significant (data not shown; P = 0·043).

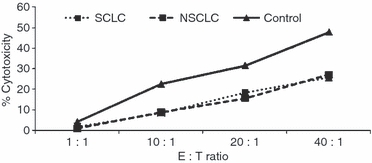

NK cell cytotoxic function and cytokine secretion in lung cancer

The PBMC from a sample of seven patients with NSCLC, 10 patients with SCLC and eight control subjects were tested for NK cytotoxic function. The mean spontaneous cytotoxicity of PBMC against 51Cr-labelled K562 target cells was significantly lower in both NSCLC and SCLC than in controls despite having similar percentages of NK cells. This was seen at an effector : target ratio of 10 : 1 (NSCLC versus controls, P = 0·02; SCLC versus controls, P = 0·008) and at a ratio of 20 : 1 (NSCLC versus controls, P = 0·04; SCLC versus controls, P = 0·028; Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Per cent specific cytotoxicity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy controls (n = 8), patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; n = 7) and patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC; n = 10) against 51Cr-labelled K562 target cells.

Natural killer cells were purified from nine patients with NSCLC and eight healthy controls; cells were 92–96% CD56+ cells with < 0·1% T-cell contamination. Following stimulation with HeLa cells at a 1 : 1 ratio, supernatants were assayed for a panel of cytokines. The only notable difference was that mean levels of IL-12(p40) were significantly higher in supernatants from patients with NSCLC than from controls (14·7 versus 4·9 pg/ml; P = 0·031).

Discussion

Although the proportions of NK cells in both groups of patients with lung cancer were not significantly lower than in healthy controls, several aspects of their function were impaired which, alone or in combination, would be expected to result in reduced activity against autologous tumour cells. The cytotoxic function against HLA-negative K562 target cells was reduced, as were perforin A and granzymes, both essential components of the Fas-independent lytic pathway, IFN-γ production and the proportion of cells expressing the NCR NKp46. The latter receptor was shown to be reduced in NK cell clones with decreased cytotoxic function derived from a patient with NSCLC.16 Defective IFN-γ production has been found in both T cells and NK cells in lung cancer,17,18 in one report resulting from reduced expression of CD3ζ.18 Any role of CD3ζ in the reduced IFN-γ expression in the present study is unknown and would be interesting to investigate.

The increased expression of KIRs by NK cells from patients with lung cancer would also potentially reduce cytotoxic function in the presence of appropriate class I HLA expression by tumour cells by delivering inhibitory signals to a greater proportion of NK cells. However, this would be contingent upon inhibitory receptor expression as defined by positivity with the anti-CD158 antibodies, which may also recognize the activating forms of the receptors, KIR2DS1 and KIR2DS2. Also, there is significant down-regulation of class I HLA in lung cancer, which has been associated with increased survival.19 This would implicate NK cells rather than cytotoxic T cells in protection against tumour growth and, in the absence of tumour cell class I HLA expression, increased inhibitory KIR expression would be ineffective at inhibiting NK cell killing. We have recently shown that there is an increased incidence of the combination of the high-affinity receptor–ligand pair KIR2DL1-HLA-C2 in NSCLC20 whereas here we have found an increased percentage of NK cells expressing the lower affinity KIR2DL2/3, which would in addition lead to a reduction in tumour cell killing via the complementary receptor–ligand pair in the presence of continued tumour cell HLA-C expression. The lower percentage of NK cells expressing CD158b in patients with more advanced tumours would potentially allow a greater degree of tumour cell killing if it were not for the reduced lytic function, although total NK cell numbers were also significantly reduced with advancing stage in both NSCLC and SCLC.

The KIR A haplotype contains mainly inhibitory KIRs whereas the B haplotype also contains several activating KIRs.21 The higher percentage of CD158b+ NK cells in patients with NSCLC having the BX KIR haplotypes may result in an increased inhibitory capacity in cells also expressing a range of activating KIRs as inhibitory receptors are normally dominant.5 Levels of CD158e on NK cells were significantly higher in patients with haplotype AA in NSCLC compared with controls, potentially resulting in stronger inhibition of NK cell killing. It is possible that patients with NSCLC with AA haplotypes have certain KIR alleles that are responsible for giving the high levels of CD158e. It has been observed that four KIR3DL1 alleles (KIR3DL1*001,002,003 and 008) are associated with a high percentage of NK cells expressing KIR3DL1 at the cell surface. In contrast, the alleles KIR3DL1*004, 005, 006 and 007 have been shown to be associated with low or no detectable KIR3DL1,22 as seen in a number of patients and controls (Figs 3 and 4). It would be of interest to investigate any differences in the KIR3DL1 allelic genotypes between lung cancer patients and normal subjects. However, median levels of CD158e were higher in SCLC patients with BX haplotypes compared with controls. This would again potentially increase the inhibitory potential in patients whose NK cells are able to express several activating KIRs.

The mean ages of patients with NSCLC and SCLC in the study were 66 ± 8·6 and 67 ± 9·8 years, respectively. Although the majority of the healthy controls were younger, we are confident that the differences in KIR expression seen in patients with lung cancer are predominantly not a result of age-related effects. No significant differences in NK cell parameters were found when healthy controls were subdivided according to age (data not shown) and previous studies found no differences in CD158b expression between groups of healthy donors aged between 20–30 and 70–85 years,23 and between 18–60 and 60–80 years24 although in two studies KIR expression in donors over 65 years was found to be increased.25,26 However, there are conflicting reports regarding age-related changes in NK cell IFN-γ production, which may be increased,27 decreased28,29 or unaltered,24 despite a significant decrease in CD56bright cells.24 We previously reported that perforin levels were significantly decreased in a healthy population aged between 73 and 77 years compared with younger subjects,30 although perforin induction in response to IL-2 is reportedly unaffected in the elderly.28 It has been suggested that maintained NK cell levels in the elderly are associated with good health.31

Many studies have reported that KIR expression can be modulated by HLA genotype. The frequency of NK cells expressing KIR2DL1 (CD158a) in donors who possessed its HLA-C2 ligand was found to be greater than in donors who lacked HLA-C2 alleles.32 A similar result was found in the frequency of NK cells expressing KIR3DL1 (CD158e) in the presence or absence of its ligand.33 Here, the frequency of CD158b+ NK cells was higher in the presence of its ligand HLA-C1 in NSCLC compared with normal subjects but so was the frequency in the absence of its ligand, indicating that this was not only attributable to licensed NK cells.34 When CD158e+ NK cells were enumerated, there was only a significantly higher percentage in the presence of the HLA-Bw4I ligand in patients with NSCLC compared with controls. It is not clear whether Bw4T or Bw4I alleles provide a stronger inhibitory signal for CD158e+ NK cells35,36 but in this study it would be suggested that expression of Bw4I alleles by NSCLC cells could provide an inhibitory signal to KIR3DL1+ NK cells, leading to reduced killing of tumour cells. This would be reinforced by the significantly increased levels of CD158e in positive cells in the presence of Bw4. A similar increase in KIR3DL1+ NK cells has been reported in normal subjects but, more particularly, in HIV-positive patients in the presence of HLA-Bw4I.37

Although the percentage of NK cells expressing KIRs is thought to remain constant,38 it has been demonstrated that levels of KIRs on CD16+ CD56bright cells increased about 10% after being treated with IL-2 + IL-15 + IL-12 for 6 days.39 In addition, IL-2 + IL-18 have the ability to up-regulate KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL2 on NK cells and also increase the percentage of NK cells that express KIR2DL1 and KIR2DL2.40 The possibility remains that increased levels of these cytokines in vivo may have been responsible for the higher levels of KIR expression in lung cancer patients. The decrease in proportions of KIR+ NK cells with advancing cancer stage may be related to reduced production of these pro-inflammatory cytokines as disease progresses. Similar increases in proportions of NK cells expressing CD158a have been reported in patients with malignant melanoma.41 In this context, the significantly higher levels of IL-12 p40 produced by NK cells from patients with NSCLC may have been inhibitory to anti-tumour responses as p40 homodimers are able to bind to IL-12 receptors but without stimulatory activity.42

In the light of the above discussion, in addition to the functional defects in NK cells in lung cancer, the increased expression of CD158b and CD158e is also likely to inhibit NK cell function in the presence of continued tumour cell class I HLA expression. The reduced IFN-γ production may in turn indirectly prevent activation of T-cell function against tumour cells. Also of relevance is the capacity of NK cells to migrate to tumour sites and studies of NSCLC patients have shown specifically reduced infiltration of NK cells, but not T cells, into tumours.43 A better prognosis was found for patients with higher levels of CD57+ cells,44 although expression of this marker is not confined to NK cells. A recent phase I trial of allogeneic NK cells in patients with NSCLC has shown promising results.45 In the present study, only peripheral blood NK cell populations were studied and in future work it would be of great interest to compare these with NK cells infiltrating lung tumours or in malignant pleural effusions.

Acknowledgments

Lucy Berresford and Dawn Porter coordinated collection of patient samples from Aintree and Whiston Hospitals, respectively. There are no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL-12

interleukin-12

- KIR

killer immunoglobulin-like receptors

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- NK

natural killer

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PE

phycoerythrin

- SCLC

small cell lung cancer

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokoyama WM, Plougastel BF. Immune functions encoded by the natural killer gene complex. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:304–16. doi: 10.1038/nri1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burshtyn DN, Scharenberg AM, Wagtmann N, Rajagopalan S, Berrada K, Yi T, Kinet JP, Long EO. Recruitment of tyrosine phosphatase HCP by the killer cell inhibitor receptor. Immunity. 1996;4:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80300-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanier LL, Corliss BC, Wu J, Leong C, Phillips JH. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature. 1998;391:703–7. doi: 10.1038/35642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhrberg M. The KIR gene family: life in the fast lane of evolution. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:10–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bix M, Liao NS, Zijlstra M, Loring J, Jaenisch R, Raulet D. Rejection of class I MHC-deficient haemopoietic cells by irradiated MHC-matched mice. Nature. 1991;349:329–31. doi: 10.1038/349329a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sher T, Dy GK, Adjei AA. Small cell lung cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:355–67. doi: 10.4065/83.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschowitz EA, Yannelli JR. Immunotherapy for lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:224–32. doi: 10.1513/pats.200806-048LC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons O, Magee M, Nemunaitis J. Current vaccine updates for lung cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9:323–35. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Q, Goding SR, Hokland ME, Basse PH. Antitumor activity of NK cells. Immunol Res. 2006;36:13–25. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sodeur S, Ullrich S, Gustke H, Zangemeister-Wittke U, Schumacher U. Increased numbers of spontaneous SCLC metastasis in absence of NK cells after subcutaneous inoculation of different SCLC cell lines into pfp/rag2 double knock out mice. Cancer Lett. 2009;282:146–51. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferson M, Edwards A, Lind A, Milton GW, Hersey P. Low natural killer-cell activity and immunoglobulin levels associated with smoking in human subjects. Int J Cancer. 1979;23:603–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu LM, Zavitz CC, Chen B, Kianpour S, Wan Y, Stämpfli MR. Cigarette smoke impairs NK cell-dependent tumor immune surveillance. J Immunol. 2007;178:936–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrega P, Morandi B, Costa R, et al. Natural killer cells infiltrating human nonsmall-cell lung cancer are enriched in CD56bright CD16− cells and display an impaired capability to kill tumor cells. Cancer. 2008;112:863–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyton RJ, Altmann DM. Natural killer cells, killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and human leucocyte antigen class I in disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Maux Chansac B, Moretta A, Vergnon I, et al. NK cells infiltrating a MHC class I-deficient lung adenocarcinoma display impaired cytotoxic activity toward autologous tumor cells associated with altered NK cell-triggering receptors. J Immunol. 2005;175:5790–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caras I, Grigorescu A, Stavaru C, Radu DL, Mogos I, Szegli G, Salageanu A. Evidence for immune defects in breast and lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:1146–52. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0556-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciszak L, Kosmaczewska A, Werynska B, Szteblich A, Jankowska R, Frydecka I. Impaired zeta chain expression and IFN-gamma production in peripheral blood T and NK cells of patients with advanced lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramnath N, Tan D, Li Q, Hylander BL, Bogner P, Ryes L, Ferrone S. Is downregulation of MHC class I antigen expression in human non-small cell lung cancer associated with prolonged survival? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:891–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Omar S, Middleton D, Marshall E, Porter D, Xinarianos G, Raji O, Field JK, Christmas SE. Associations between genes for killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and their ligands in patients with solid tumors. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:976–81. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parham P. MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:201–14. doi: 10.1038/nri1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardiner CM, Guethlein LA, Shilling HG, Pando M, Carr WH, Rajalingam R, Vilches C, Parham P. Different NK cell surface phenotypes defined by the DX9 antibody are due to KIR3DL1 gene polymorphism. J Immunol. 2001;166:2992–3001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li G, Yu M, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Epigenetic regulation of killer immunoglobulin-like receptor expression in T cells. Blood. 2009;114:3422–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Garff-Tavernier M, Béziat V, Decocq J, et al. Human NK cells display major phenotypic and functional changes over the life span. Aging Cell. 2010;9:527–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz CT, Moore MB, Bradley S, Shelton BJ, Lutgendorf SK. Reciprocal age related change in natural killer cell receptors for MHC class I. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:722–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mariani E, Monaco MC, Cattini L, Sinoppi M, Facchini A. Distribution and lytic activity of NK cell subsets in the elderly. Mech Ageing Dev. 1994;76:177–87. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)91592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayhoe RP, Henson SM, Akbar AN, Palmer DB. Variation of human natural killer cell phenotypes with age: identification of a unique KLRG1-negative subset. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:676–81. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solana R, Mariani E. NK and NK/T cells in human senescence. Vaccine. 2000;18:1613–20. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mocchegiani E, Malavolta M. NK and NKT cell functions in immunosenescence. Aging Cell. 2004;3:177–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rukavina D, Laskarin G, Rubesa G, et al. Age-related decline of perforin expression in human cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Blood. 1998;92:2410–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mocchegiani E, Giacconi R, Cipriano C, Malavolta M. NK and NKT cells in aging and longevity: role of zinc and metallothioneins. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:416–25. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parham P. Taking license with natural killer cell maturation and repertoire development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yawata M, Yawata N, Draghi M, Little AM, Partheniou F, Parham P. Roles for HLA and KIR polymorphisms in natural killer cell repertoire selection and modulation of effector function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:633–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsson AH, Yokoyama WM. Natural killer cell tolerance licensing and other mechanisms. Adv Immunol. 2009;101:27–79. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luque I, Solana R, Galiani MD, González R, García F, López de Castro JA, Peña J. Threonine 80 on HLA-B27 confers protection against lysis by a group of natural killer clones. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1974–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella M, Longo A, Ferrara GB, Strominger JL, Colonna M. NK3-specific natural killer cells are selectively inhibited by Bw4-positive HLA alleles with isoleucine 80. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1235–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alter G, Rihn S, Walter K, et al. HLA class I subtype-dependent expansion of KIR3DS1+ and KIR3DL1+ NK cells during acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2009;83:6798–805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moretta A, Poggi A, Pende D, et al. Identification of four subsets of human CD3− CD16+ natural killer (NK) cells by the expression of clonally distributed functional surface molecules: correlation between subset assignment of NK clones and ability to mediate specific alloantigen recognition. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1589–98. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunne J, Lynch S, O'Farrelly C, Todryk S, Hegarty JE, Feighery C, Doherty DG. Selective expansion and partial activation of human NK cells and NK receptor-positive T cells by IL-2 and IL-15. J Immunol. 2001;167:3129–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chrul S, Polakowska E, Szadkowska A, Bodalski J. Influence of interleukin IL-2 and IL-12 + IL-18 on surface expression of immunoglobulin-like receptors KIR2DL1, KIR2DL2, and KIR3DL2 in natural killer cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2006;2006:46957. doi: 10.1155/MI/2006/46957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konjević G, Mirjacić Martinović K, Jurisić V, Babović N, Spuzić I. Biomarkers of suppressed natural killer (NK) cell function in metastatic melanoma: decreased NKG2D and increased CD158a receptors on CD3− CD16+ NK cells. Biomarkers. 2009;14:258–70. doi: 10.1080/13547500902814658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ling P, Gately MK, Gubler U, et al. Human IL-12 p40 homodimer binds to the IL-12 receptor but does not mediate biologic activity. J Immunol. 1995;154:116–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esendagli G, Bruderek K, Goldmann T, Busche A, Branscheid D, Vollmer E, Brandau S. Malignant and non-malignant lung tissue areas are differentially populated by natural killer cells and regulatory T cells in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villegas FR, Coca S, Villarrubia VG, Jiménez R, Chillón MJ, Jareño J, Zuil M, Callol L. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;35:23–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iliopoulou EG, Kountourakis P, Karamouzis MV, et al. A phase I trial of adoptive transfer of allogeneic natural killer cells in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:1781–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]