Abstract

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) is generally expressed in all EBV-associated tumours and is therefore an interesting target for immunotherapy. However, evidence for the recognition and elimination of EBV-transformed and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) specific for endogenously presented EBNA1-derived epitopes remains elusive. We confirm here that CTLs specific for the HLA-B35/B53-presented EBNA1-derived HPVGEADYFEY (HPV) epitope are detectable in the majority of HLA-B35 individuals, and recognize EBV-transformed B lymphocytes, thereby demonstrating that the GAr domain does not fully inhibit the class I presentation of the HPV epitope. In contrast, BL cells are not recognized by HPV-specific CTLs, suggesting that other mechanisms contribute to providing a full protection from EBNA1-specific CTL-mediated lysis. One of the major differences between BL cells and lymphoplastoid cell lines (LCLs) is the proteasome; indeed, proteasomes from BL cells demonstrate far lower chymotryptic and tryptic-like activities compared with proteasomes from LCLs. Hence, inefficient proteasomal processing is likely to be the main reason for the poor presentation of this epitope in BL cells. Interestingly, we show that treatments with proteasome inhibitors partially restore the capacity of BL cells to present the HPV epitope. This indicates that proteasomes from BL cells, although less efficient in degrading reference substrates than proteasomes from LCLs, are able to destroy the HPV epitope, which can, however, be generated and presented after partial inhibition of the proteasome. These findings suggest the use of proteasome inhibitors, alone or in combination with other drugs, as a strategy for the treatment of EBNA1-carrying tumours.

Keywords: Burkitt's lymphoma, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1, Epstein–Barr virus, proteasome inhibitors

Introduction

The Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a widespread virus that establishes life-long persistent infections in B lymphocytes in the vast majority of human adults. These EBV-infected B cells can proliferate in vitro, giving rise to lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) that express at least nine latency-associated viral antigens: the nuclear antigens EBNA1 to EBNA6 and the membrane proteins LMP1, LMP2A and LMP2B.1

The proliferation of EBV-infected cells is monitored in vivo by T lymphocytes that specifically recognize viral antigens as peptides derived from the processing of endogenously expressed viral proteins presented on the surface of the target cell as a complex with MHC class I molecules.2 In particular, EBNA3, EBNA4 and EBNA6 (also known as EBNA3A, 3B and 3C) contain immunodominant epitopes for cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses over a wide range of HLA backgrounds. In contrast, EBNA2, EBNA5, LMP1 and LMP2 are subdominant targets that are presented in the context of a limited number of HLA restrictions.3–7 Conflicting with previous observations,4,5,8 CTL responses against EBNA1 have also been detected in healthy EBV-seropositive individuals9–13 but, so far, the poor recognition and killing of the target cells that naturally express EBNA1 by EBNA1-specific CTL cultures suggest a poor presentation of EBNA1-derived CTL epitopes. This has been attributed to the presence of a Gly-Ala repeat (GAr) sequence, which prevents the presentation of EBNA1-derived antigenic peptides by MHC class I molecules. Furthermore, this GAr-mediated function has been linked to its capacity to prevent EBNA1 synthesis14,15 and block proteasomal degradation.16,17 Although the role of the GAr domain on the stability/turnover of EBNA1 has only partially been clarified, it is now evident that EBNA1 is immunogenic and capable of inducing CD8-mediated cells responses. As EBNA1 is the only antigen expressed in all EBV-associated tumours, and therefore represents an ideal tumour-rejection target for immunotherapy against EBV-associated malignancies, elucidation of the mechanisms by which EBNA1-specific CTLs recognize naturally EBNA1-expressing cells remains crucial.18,19

To explore target cell recognition by EBNA1-specific CTL cultures, CTLs specific for the EBNA1-derived HPVGEADYFEY (HPV), amino acids 407–417, presented by HLA-B35.01 and HLA-B53, were chosen as a model, as recognition of this immunodominant EBV epitope has been documented in the majority of B35-positive, EBV-seropositive donors, and during primary infection.9,20

Herein we demonstrate that the majority of HLA-B35 positive donors do indeed respond to this epitope, thereby confirming the importance of EBNA1 as target of EBV-positive malignancies. We also show that HPV-specific CTLs recognize and kill LCLs but not Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells which, despite possessing proteasomes with much lower chymotryptic and tryptic-like activities than LCLs, were shown to degrade the HPV epitope. Interestingly, a partial sensitivity to HPV-specific CTLs was demonstrated in BL cells treated with proteasome inhibitors.

In conclusion, our study suggests that antigen presentation in BL cells may be restored by the use of proteasome inhibitors, making them attractive candidates for inclusion in combined drug regimens against EBNA1-positive malignancies.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Lymphoblastoid cell lines were obtained by infection of lymphocytes from HLA-typed donors with culture supernatants of a B95.8 virus-producing cell line, cultured in the presence of 0.1 μg/ml cyclosporin A (Sandoz International GmbH, Holzkirchen, Germany). The LCLs and the BL cell lines (BJAB B95.8 and Jijoye) were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mm glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) -activated blasts were obtained by stimulation of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) with 1 μg/ml purified PHA (Wellcome Diagnostics, Dartford, UK) for 3 days, and expanded in medium supplemented with human recombinant interleukin-2 (Proleukin, Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, CA) as previously described.3

Proteasome purification

Cell were washed in cold PBS and resuspended in buffer containing 50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7·5), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 2 mm ATP and 250 mm sucrose. Glass beads equivalent to the volume of the cell suspension were added, and the mixture was vortexed for 1 min at 4°. Beads and cell debris were removed by 5 min centrifugation at 1000 g, followed by 20 min of centrifugation at 10 000 g. Lysates were cleared by ultracentrifugation for 1 hr at 100 000 g, and supernatants were then ultracentrifuged for 5 hr at 100 000 g.21 Proteasome-containing pellets were resuspended in 0·5 ml homogenization buffer [50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7·5), 100 mm KCl, 15% glycerol]. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchononic acid protocol (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Enzymatic assays

The chymotrypsin-like and trypsin-like activities of purified proteasomes were tested using the fluorogenic substrates Suc-LLVY-AMC and Boc-LRR-AMC, respectively, as previously described.21 Fluorescence was determined using a fluorimeter (Spectrafluor plus; Tecan, Salzburg, Austria). Proteasome activity is expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units.

Peptide degradation

In vitro degradation of HPVGEADYFEYHQEGG (HPV + 5) was performed using 150 μg of the peptide and 150 μg purified proteasomes in 450 μl activity buffer at 37°. At different time-points, 80-μl samples were collected, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2 volumes of ethanol at 0°. 240 μl of digestion mixtures were centrifuged at 500 g, and 80 μl of supernatant was collected and analysed by HPLC.22

Synthetic peptides

Peptides were synthesized by the solid-phase method and purified to > 98% purity by HPLC, as previously described.23 Structural verification was performed by elemental and amino acid analysis and mass spectrometry. Peptide stocks were prepared in DMSO at 10−2 m concentration and maintained at −20°.

Western blot assay

Equal amounts of proteins or equal amounts of purified proteasomes were loaded onto a 12% SDS–PAGE and electroblotted onto Protran nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell Microscience, Keene, NH). Blots were probed with antibodies specific for α, LMP2, LMP7, multicatalytic endopeptidase complex 1 (MECL1) subunits, proteasome activator 28 (PA28) α-β, 19S, antigen peptide transporter 1 (TAP1) and TAP2, and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden).22

Generation of memory CTL cultures

Monocyte-depleted PBLs from HLA B35-restricted EBV-seropositive subjects were plated in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), at 3 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates, and stimulated with either EBNA1-derived HPVGEADYFEY (HPV, amino acids 407–417) or EBNA3-derived YPLHEQHGM (YPL, amino acids 458–466) peptide. Cultures were restimulated after 7 and 14 days, and the medium was supplemented from day 8 with 10 U/ml recombinant interleukin-2 (Chiron). On days 14 and 21, T-cell cultures were tested for CTL activity by cytotoxicity assay. The EBV specificities and HLA class I restriction of the CTL preparations were then investigated by testing their cytotoxic activities against PHA-activated blasts.13

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic activity was tested by a standard 5-hr 51Cr-release assay, as previously described.24 Briefly, target cells were labelled with 0.1 μCi/106 cells of Na251CrO4 for 90 min at 37° and, where indicated, were pulsed for 45 min with 10−6 m of the different peptides at 37°. Cells were then washed, and 4 × 103 cells were used as targets of each CTL at different effector to target ratios. The per cent specific lysis was calculated as 100 × [(c.p.m. sample)−(c.p.m. medium)/(c.p.m. Triton X-100)−(c.p.m. medium)], where c.p.m. represents counts/min. Spontaneous release was always < 20% in all cases. None of the tested peptides affected spontaneous release.

Interferon-γ ELISPOT

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot-forming cell assay [ELISPOT; for interferon-γ (IFN-γ)] was carried out using commercially available kits (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 96-well nitrocellulose plates were coated with 5 μg/ml anti-IFN-γ, and maintained at 4° overnight. The following day the plates were washed four times with PBS and blocked for 2 hr with 10% fetal bovine serum-supplemented RPMI-1640 at 37°. The CTLs were added to the wells (in triplicate) at a ratio of 10 : 1 and incubated with target cells at 37° for 24 hr. Controls were represented by cells incubated with concanavalin A (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO; 5 μg/ml) (positive control), or with the medium alone (negative control). Spots were read using an ELISPOT reader (A.EL.VIS GmbH, Hannover, Germany). Results are expressed as net number of spot-forming units/106 cells.15

Immunofluorescence detection of HLA-ABC molecules

Surface expression of HLA-ABC molecules was detected by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-human HLA-ABC mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Mean logarithmic fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis (Bryte HS; Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy).13

Results

Induction of EBNA1-specific memory CTL responses directed to the HLA-B35- and HLA-B53-presented HPV CTL epitope

It has been previously demonstrated that the HPV epitope, derived from the EBNA1 antigen (amino acid 407–417) and presented by HLA-B35 and HLA-B53 alleles of the B5 cross-reactive group, is one of the targets of EBNA1-specific CTL responses in healthy EBV-seropositive individuals.20

To identify specific responses to this epitope and to obtain HPV-specific CTL cultures for further evaluation, we investigated the presence of HPV-specific memory CTL responses in a panel of HLA-B35 healthy EBV-seropositive individuals. To this end, PBLs obtained from nine healthy HLA-B35 positive, EBV-seropositive donors (Table 1) were stimulated with the HPV peptide.24 As control, parallel stimulations were performed using the HLA-B35-presented YPL epitope derived from the EBNA3A antigen.5 The specificity of CTL cultures was tested after three stimulations using standard 51Cr-release assays against autologous PHA-blasts, pulsed or not with the relevant synthetic peptide.

Table 1.

List of healthy HLA-B35 EBV-seropositive donors and their responses against HPV and YPL epitopes

| Specific CTL response cytotoxic activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | HLA type | EBNA1 epitope HPVGEADYFEY | EBNA3 epitope YPLHEQHGM |

| 1 | A32, B13, B35 | − | − |

| 2 | A1, A24, B14, B35 | − | + |

| 3 | A24, B35, B37, B35 | + | − |

| 4 | A3, A24, B27, B35 | − | − |

| 5 | A2, B18, B35 | + | + |

| 6 | A24, B7, B35 | + | − |

| 7 | A2, A24, B35 | + | + |

| 8 | A3, A10, B18, B35 | + | + |

| 9 | A2, A11, B57, B35 | + | nd |

CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; EBNA, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen; nd, not determined.

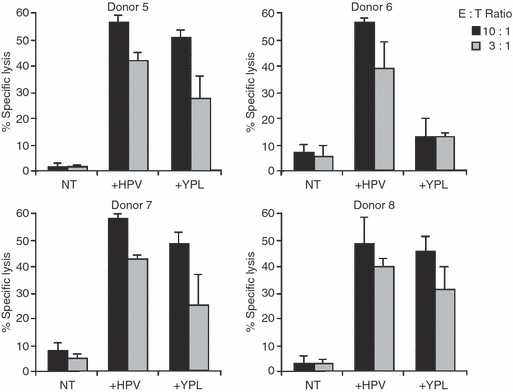

As shown in Fig. 1, HPV-pulsed PHA blasts were efficiently lysed by representative CTL cultures obtained from donors 5, 6, 7 and 8. Three of these donors also responded to the YPL epitope. Overall, these stimulations yielded HPV-specific CTL responses in six of the nine donors tested (Table 1). It should be noted that responses to the EBNA3A-derived YPL epitope were detected in four of the eight donors tested (Table 1). These results suggest that the EBNA1-derived HPV epitope may be a relevant target of EBV-specific CTL responses.

Figure 1.

The HPVGEADYFEY (HPV) eptiope -specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) cultures obtained from four different donors. As control, parallel stimulations were performed using the HLA-B35 presented YPLHEQHGM (YPL) epitope derived from the Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 3A (EBNA3A). The CTL cultures were obtained after three consecutive stimulations, and were then tested in triplicate against untreated, HPV or YPL-pulsed autologous phytohaemagglutinin blasts. Results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis obtained at the indicated effector : target ratio. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown.

Recognition of LCL and BL cells by HPV-specific CTL cultures

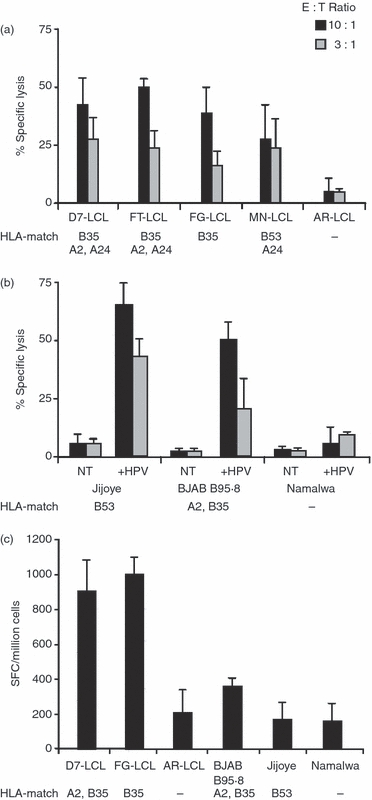

To investigate the presentation of the HPV CTL epitope in EBV-positive cells, HLA-B35 or HLA-B53 positive LCLs and BL cells were used as targets of HPV-specific CTL cultures obtained from donors 5 and 7. We found, in the 5-hr 51Cr-release assay that unmanipulated HLA-B35- and HLA-B53-matched LCLs were lysed by HPV-specific CTL cultures whereas BL cells were not recognized, suggesting that the HPV epitope is poorly presented at the surface of BL cells (Fig. 2a,b). To exclude poor sensitivity to lysis of BL lines, we evaluated the killing of BLs loaded with the synthetic HPV epitope by cytotoxic assay. We found that HPV-pulsed BL cells were recognized by HPV-specific CTLs, indicating that BL cells are sensitive to lysis and able to present the HPV T-cell epitope when exogenously added (Fig. 2b). The IFN-γ production assays have been mainly used in studies documenting the presentation of EBNA1-derived MHC-I-presented CTL epitopes because it is considered a more sensitive indicator of target cell recognition.10–12 Therefore, we tested whether recognition of EBNA1-expressing BL cells could be revealed by monitoring IFN-γ release in ELISPOT assays. To this end, HPV-specific CTLs and matched LCLs and BL cells were seeded at an effector : target ratio of 10 : 1, and the number of HPV-specific IFN-γ-producing cells was evaluated after 24 hr. As shown in Fig. 2(c), release of IFN-γ was specifically induced by HLA-B35-matched LCLs while HLA-B35-matched and HLA-B53-matched BL cells did not stimulate IFN-γ release, thereby confirming the poor presentation of this epitope in BL cell lines.

Figure 2.

Recognition of lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells by HPVGEADYFEY (HPV) epitope-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) cultures. (a) HLA-B35-positive or HLA-B53-positive LCLs and (b) BL cells were used in a 5-hr 51Cr-release assay as targets of HPV-specific CTL cultures obtained from donors 5 and 7. Target cells were tested either after HPV-pulse (+HPV) or no treatment (NT). Results are expressed as the percentage of specific lysis obtained at the indicated effector : target ratio. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown. (c) Matched or mismatched LCLs and BL cells were co-cultured for 24 hr with HPV-specific CTL at an effector : target ratio of 10 : 1. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release was detected by ELISPOT. Results are expressed as net spot number (SFC)/106 cells. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown.

As a whole, these results demonstrate that the EBNA1-derived HPV epitope is generated and presented in LCLs but not in BL cells. This suggests that HPV generation does not exclusively depend on the presence of the GAr domain.

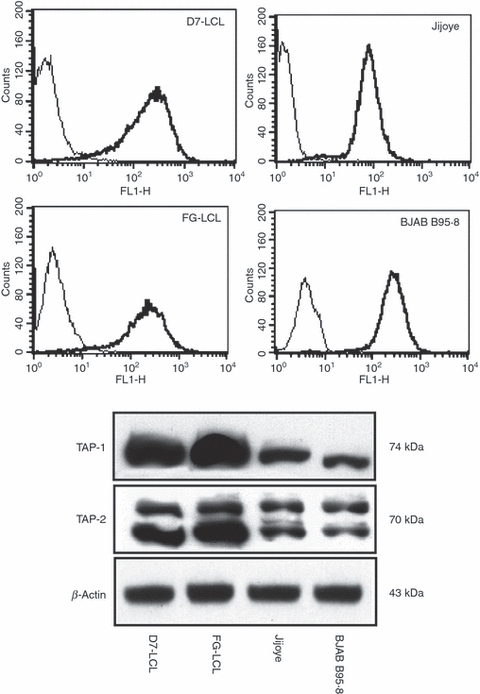

Expression of HLA class I and TAP molecules

Loss or down-regulation of HLA class I is one of the routes of immune escape in a variety of human tumours, including BL cell lines.25–28 Therefore, the surface expression of class I molecules in BL cells and LCLs was tested by indirect immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 3 and supplementary material, see Table S1, Jijoye cells expressed lower amounts of class I molecules whereas BJAB B95.8 cell lines showed similar levels of total HLA class I molecules, compared with LCLs. However, significant levels of lysis were achieved by the addition of HPV peptide to BL cells, thereby suggesting that sufficient levels of class I molecules were expressed at the cell surface (Fig. 2b).

Figure 3.

HLA class I and antigen peptide transporter (TAP) heterodimer expression in lymphoplastoid cell lines (LCLs) and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells. In the upper panel, surface expression of HLA-ABC molecules as detected by indirect immunofluorescence is shown. Mean logarithmic fluorescence intensity was determined by FACS analysis; thin and thick lines indicate the isotype control and the HLA-ABC signal, respectively, for each cell line. In the lower panel, expression of TAP-1 and TAP-2 in two LCLs and in two BL cell lines, as detected by Western blot analysis, is shown. β-Actin was used as loading control. One representative experiment out of three is shown.

As the TAP1/TAP2 heterodimer is required for translocation of the majority of peptides from the cytosol into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, lack of these proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum could also be a reason for limited presentation of MHC-I peptides.28 To investigate this theory, TAP expression was evaluated by probing Western blots of total cell extracts with TAP1-specific and TAP2-specific antibodies, as shown in Fig. 3. The obtained results demonstrate that Jijoye and BJAB B95.8 cells expressed both TAP proteins, albeit to a lesser degree than LCLs, suggesting that lack of presentation of the HPV peptide antigen is not the result of a loss of TAP1/TAP2 expression. These results suggest that the expression of class I molecules and TAP, although very relevant in the presentation of MHC-I/peptide complexes, may only partially affect the presentation of the EBNA1-derived HPV epitope. Indeed, treatment of cells with IFN-γ (Fig. 6), which increases HLA class I molecules and TAP expression, does not sensitize target cells to lysis by HPV-specific CTLs. Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated that BJAB cells are able to present the HPV epitope if they express a GAr-deleted form of EBNA1, suggesting that the lower expression of class I molecules and TAPs may only partially contribute to lack of the HPV epitope presentation.13

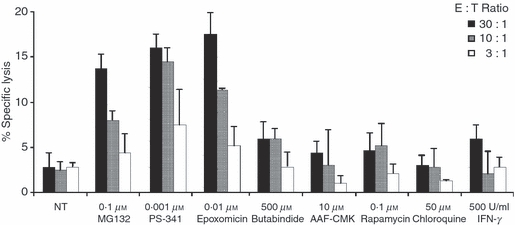

Figure 6.

Effect on HPVGEADYFEY (HPV) epitope presentation in Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells by modulation of different steps of the antigen-processing pathways. HPV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) cultures were tested against Jijoye cells treated overnight or not with the indicated molecules. Results are expressed as the per cent specific lysis obtained at the indicated effector : target ratio. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown.

Expression and activity of proteasomes from LCLs and BL cells

It has previously been demonstrated that BL cells express proteasomes with different subunit composition and enzymatic activity, perhaps resulting in the generation of a distinct set of MHC-I binding peptides.21,29

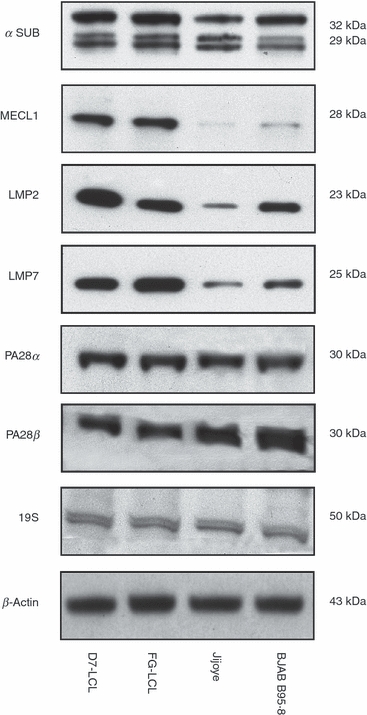

For this reason, we investigated the levels of expression of IFN-γ-regulated β subunits (LMP2, LMP7 and MECL-1) and proteasome regulators (PA28 α-β, 19S) in LCLs and BL cells by Western blotting. As shown in a representative experiment (Fig. 4), Jijoye and BJAB B95.8 cell lines expressed levels of proteasomes comparable to those found in LCLs, as shown by the detection of similar amounts of the constitutively expressed α subunits. However, a significant down-regulation of MECL-1 and a less marked down-regulation of LMP2 and LMP7 were detected in BL cell lines. To investigate whether these differences in the expression of subunit composition correlated with differences in enzymatic activity, we analysed the chymotryptic- and tryptic-like activities of proteasomes semi-purified from LCLs and BL cells in enzyme kinetics assays, using Suc-LLVY-AMC and Boc-LRR-AMC as reference substrates.

Figure 4.

Expression of proteasome subunits and regulators in Burkitt's lympoma (BL) cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines. Equal amounts of semi-purified proteasomes were loaded onto a 12% SDS–PAGE and electroblotted onto Protran nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were probed with specific antibodies, as reported in the Materials and Methods. β-Actin was used as loading control. One representative experiment out of three is shown.

Proteasomes isolated from BL cells demonstrated far lower chymotryptic-like and tryptic-like activities than proteasomes isolated from LCLs (Fig. 5). This is in agreement with the pattern of expression of the catalytic subunits in LCLs, as increased expression of LMP7 and MECL1 is associated with increased chymotryptic and tryptic activities.

Figure 5.

Proteolytic activity of proteasomes isolated from Burkitt's lympoma (BL) cells and lymphoblastoid cell lines. (a) The trypsin-like and (b) chymotrypsin-like activities of proteasomes are shown. Proteasome activity is expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units (U.A.F.). Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown.

Modulation of antigen processing may affect the presentation of the HPV epitope in BL cells

Previous results suggest that one of the major differences between BL cells and LCLs is in the expression and activity of proteasomes, which may result in poor generation of the HPV epitope. It has already been shown that modulation of antigen processing and partial inhibition of proteasomes may restore the generation of certain T-cell epitopes.30–34 For this reason, we treated BL cells with molecules that modulate various steps of the antigen-processing pathways. Specifically, Jijoye cells were treated overnight either with proteasome inhibitors (MG132, epoxomicin and PS-341), tripeptidyl peptidase II inhibitors (butabindide and AAF-CMK), a lysosomal acidification inhibitor (chloroquine), an autophagic process inducer (rapamycin) or IFN-γ, which increases proteasome and ERAP activities as well as HLA class I and TAP expression. All drugs were used at the selected concentrations, which correspond to their known biological effect without effects on cell viability. As shown in Fig. 6, only partial inhibition of proteasomes leads to an increased recognition of Jijoye cells by HPV-specific CTLs, whereas all other treatments failed to affect target cell lysis. Similar results were obtained with BJAB B95.8 cells, whereas BL cells negative for HLA-B53 and HLA-B35, which were used as a negative control in all assays, were unaffected by these treatments (not shown).

These results suggest that proteasomes from BL cells, although less efficient in degrading reference substrates than proteasomes from LCLs, destroy the HPV epitope, which can, however, be generated and presented after partial inhibition of the proteasomes.

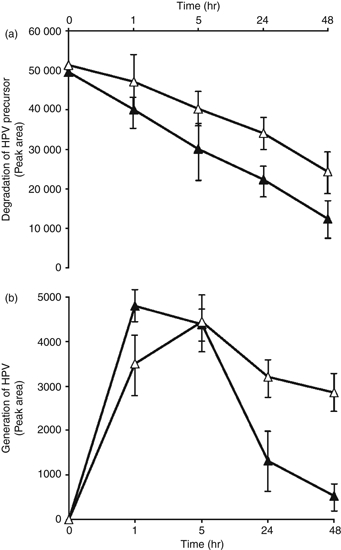

In vitro generation of the HPV epitope by proteasomes isolated from BL cells

To evaluate whether proteasomes from BL cells are able to generate the HPV epitope, we analysed the in vitro degradation of an HPV peptide precursor featuring five amino acids at the C terminus (HPV + 5). Proteasomes were semi-purified from Jijoye cells treated or not with epoxomicin under the same conditions inducing HPV-specific lysis. Subsequently, the in vitro HPV precursor degradation was evaluated at different time-points by HPLC analysis. As shown in Fig. 7, the HPV precursor was degraded in a time-dependent fashion. Proteasomes isolated from Jijoye cells and treated with epoxomicin were still capable of degrading the HPV precursor, albeit to a lesser extent. Interestingly, the appearance of a single peptide was evident during the HPV + 5 degradation. As this peptide eluted from the HPLC column with the same retention time as the HPV peptide, it was identified as the HPV epitope, a hypothesis confirmed by mass spectroscopy (not shown).

Figure 7.

In vitro generation of the HPVGEADYFEY (HPV) epitope by proteasomes isolated from Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) cells. (a) The HPV + 5 peptide (HPV precursor) was incubated with proteasomes purified from Jijoye, treated with epoxomicin 0·01 μm (white triangle) or untreated (black triangle). The HPV precursor degradation was monitored at different time-points evaluated by HPLC analysis. Data are expressed as peak area of HPV precursor. (b) HPV generation at different time-points relating to the degradation of HPV precursor in Jijoye cells, treated with epoxomicin 0·01 μm (white triangle) or untreated (black triangle). Data are expressed as peak area of HPV, as evaluated by HPLC analysis. One representative experiment out of three is shown. Mean ± SD of three independent experiments is shown.

The generation of the HPV epitope by proteasomes isolated from untreated Jijoye cells was maximal after 1 hr and subsequently decreased in a time-dependent fashion, suggesting a further degradation to products that were undetectable under our conditions. In contrast, proteasomes isolated from Jijoye cells treated with epoxomicin still generated the HPV epitope, which was not further degraded because its presence could still be detected after 48 hr. These in vitro findings suggest that BL cells treated with proteasome inhibitors do not degrade the HPV epitope, resulting in its presentation by class I molecules.

Discussion

In this study, to assay the presentation of the EBNA1-derived, HLA-B35/B53-presented HPV epitope in its natural context, we used HPV-specific CTL cultures, generated by peptide stimulation from EBV-seropositive healthy individuals. These cultures were then tested against LCLs and EBV-positive BL cells using either cytotoxicity or IFN-γ release. In the case of EBNA1-specific T-cell responses, failure to lyse EBNA1-expressing target cells has frequently been observed,20,35 although low levels of lysis have been reported in some studies.11,12 In contrast, specific recognition of EBNA1-derived epitopes has in many cases been revealed by the induction of IFN-γ release, which is considered a more sensitive method for detecting target cell recognition.

By this approach, we confirmed that the presence of HPV-specific T-cell responses is in the same range as that seen for the immunodominant HLA-B35-restricted YPL epitope derived from EBNA3.10,11 This finding, together with the identification of other EBNA1-derived epitopes restricted by several class I alleles,9–13 further highlights the importance of EBNA1 as a target of EBV-positive malignancies, and makes evaluation of the recognition of EBV-infected cells and EBV-associated malignancies by EBNA1-specific CTLs crucial.

Hence, we set out to demonstrate that LCLs are recognized and killed by HPV-specific CTL cultures, indicating that the GAr domain affords the protein antigen only partial protection from CD8+ T-cell recognition. Therefore, in line with previous observations, our results support the idea that EBNA1-specific T-cell responses are primed in vivo by a direct interaction between the CD8 T-cell repertoire and naturally infected B cells in which endogenously expressed EBNA1 is targeted intracellularly by the proteasome, despite the presence of the GAr domain.10–12

In contrast to what was observed in LCLs, we show that BL cells are not recognized by HPV-specific CTLs, thereby suggesting that the GAr domain affords the EBNA1 antigen protection from CTL-mediated lysis in this type of cell. As it has previously been demonstrated that the stability of EBNA1, although varying in different cell lines, does not correspond to the level of generation of EBNA1-derived CTL epitopes,11 lack of presentation of the HPV epitope in BL cells should not be the result of a GAr stabilization effect of EBNA1. Instead, it should be ascribable to the particular antigen-processing machinery present in BL cells, which differs from that found in LCLs. Furthermore, deletion of the GAr domain has also been demonstrated to provoke no major effect on EBNA1 protection from degradation, suggesting that the GAr domain has other, as yet unidentified, effects.36

One of the major differences between BL cells and LCL is the proteasome.21,27,28 Indeed, using the same cells assayed for cytotoxicity, BL cells were found to present proteasomes with a different subunit composition, correlating with much lower chymotryptic and tryptic-like activities with respect to LCLs. This may result in their poor capacity to generate the HPV epitope because of presence of the GAr domain, whose deletion restores the capacity of BL cells to present the HPV epitope.13 Indeed, we previously demonstrated that BJAB cells expressing a GAr-deleted EBNA1, are recognized by HPV-specific CTLs, further confirming that low expression of HLA class I molecules and TAPs may only partially affect the presentation of the HPV epitope, which is not generated and presented in BJAB-expressing wild-type EBNA1.13 Intriguingly, we found that treatment of BL cells with proteasome inhibitors partially restores their capacity to present the EBNA1 epitope, thereby suggesting that proteasomes from BL cells, although less active against prototype substrate peptides, which only partially indicate the in vivo proteasomal activities, degrade the HPV epitope during the processing of EBNA1. It remains to be elucidated whether other EBNA1-derived CTL epitopes may be more efficiently generated and presented after partial inhibition of proteasomes or whether this effect is restricted to the HPV epitope.

In conclusion, our study, together with previous reports, strongly supports the idea that EBNA1-specific CTLs might be exploited therapeutically to target EBV-positive malignancies in combination with chemotherapy and protocols designed to restore antigen-presenting capacity in the tumour. In this context, it has been recently demonstrated that tubacin, a molecule that inhibits histone deacetylase 6, demonstrates a fairly selective capacity to induce apoptosis in BL cells, but not in LCLs.37 Furthermore, the combination of tubacin with a proteasome inhibitor induced efficient killing of BL cells,37 which are known to be resistant to proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis.21,38 These findings, together with those reported in this study, suggest that the use of proteasome inhibitors, alone or in combination with other drugs such as tubacin, may represent a strategy for the treatment of EBNA1-carrying tumours, because proteasome inhibitors, in addition to their effect as pro-apoptotic drugs, may also increase the immunogenicity of EBNA1, thereby resulting in the efficient elimination of EBNA1-positive malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the University of Ferrara and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara. We are grateful to A. Forster for editorial assistance and to Dr A. Balboni for HLA typing.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. MHC class I expression in lymphoblastoid cell line and in Burkitt's lymphoma cells.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Kieff E, Leibowitz D. Epstein–Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields BM, Knipe DN, editors. Virology. 2nd edn. Vol. 2. New York: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1889–920. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pamer E, Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:323–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gavioli R, Kurilla MG, de Campos-Lima PO, Wallace LE, Dolcetti R, Murray RJ, Rickinson AB, Masucci MG. Multiple HLA A11-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes of different immunogenicities in the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 4. J Virol. 1993;67:1572–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1572-1578.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna R, Burrows SR, Kurilla MG, Jacob CA, Misko IS, Sculley TB, Kieff E, Moss DJ. Localization of Epstein–Barr virus cytotoxic T cell epitopes using recombinant vaccinia: implications for vaccine development. J Exp Med. 1992;176:169–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray RJ, Kurilla MG, Brooks JM, Thomas WA, Rowe M, Kieff E, Rickinson AB. Identification of target antigens for the human cytotoxic T cell response to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV): implications for the immune control of EBV-positive malignancies. J Exp Med. 1992;176:157–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rickinson AB, Moss DJ. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein–Barr virus infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:405–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steven NM, Leese AM, Annels NE, Lee SP, Rickinson AB. Epitope focusing in the primary cytotoxic T cell response to Epstein–Barr virus and its relationship to T cell memory. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1801–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavioli R, De Campos-Lima PO, Kurilla MG, Kieff E, Klein G, Masucci MG. Recognition of the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigens EBNA-4 and EBNA-6 by HLA-A11-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes: implications for down-regulation of HLA-A11 in Burkitt lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5862–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blake N, Lee S, Redchenko I, et al. Human CD8+ T cell responses to EBV EBNA1: HLA class I presentation of the (Gly-Ala)-containing protein requires exogenous processing. Immunity. 1997;7:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SP, Brooks JM, Al-Jarrah H, et al. CD8 T cell recognition of endogenously expressed Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1409–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tellam J, Connolly G, Green KJ, Miles JJ, Moss DJ, Burrows SR, Khanna R. Endogenous presentation of CD8+ T cell epitopes from Epstein–Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 1. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1421–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voo K, Fu T, Wang H, Tellam J, Heslop H, Brenner M, Rooney C, Wang R. Evidence for the presentation of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 peptides to CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:459–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marescotti D, Destro F, Baldisserotto A, Marastoni M, Coppotelli G, Masucci M, Gavioli R. Characterization of an human leukocyte antigen A2-restricted Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen-1-derived cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope. Immunology. 2010;129:386–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apcher S, Komarova A, Daskalogianni C, Yin Y, Malbert-Colas L, Fåhraeus R. mRNA translation regulation by the Gly-Ala repeat of Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. J Virol. 2009;83:1289–98. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01369-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yin Y, Manoury B, Fahraeus R. Self-inhibition of synthesis and antigen presentation by Epstein–Barr virus-encoded EBNA1. Science. 2003;301:1371–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1088902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitskaya J, Coram M, Levitsky V, Imreh S, Steigerwald-Mullen PM, Klein G, Kurilla MG, Masucci MG. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen-1. Nature (London) 1995;375:685–8. doi: 10.1038/375685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levitskaya J, Sharipo A, Leonchiks A, Ciechanover A, Masucci MG. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlo A, Turrini R, Bobisse S, et al. Virus-specific cytotoxic CD4+ T cells for the treatment of EBV-related tumors. J Immunol. 2010;184:5895–902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heslop HE, Slobod KS, Pule MA, et al. Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T-cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;115:925–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blake N, Haigh T, Shaka'a G, Croom-Carter D, Rickinson A. The importance of exogenous antigen in priming the human CD8+ T cell response: lessons from the EBV nuclear antigen EBNA1. J Immunol. 2000;165:7078–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavioli R, Frisan T, Vertuani S, Bornkamm GW, Masucci MG. c-myc overexpression activates alternative pathways for intracellular proteolysis in lymphoma cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:283–8. doi: 10.1038/35060076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavioli R, Gallerani E, Fortini C, et al. HIV-1 tat protein modulates the generation of cytotoxic T cell epitopes by modifying proteasome composition and enzymatic activity. J Immunol. 2004;173:3838–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavioli R, Guerrini R, Masucci MG, Tomatis R, Traniello S, Marastoni M. High structural side chain specificity required at the second position of immunogenic peptides to obtain stable MHC/peptide complexes. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:95–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Micheletti F, Guerrini R, Formentin A, et al. Selective amino acid substitutions of a subdominant Epstein–Barr virus LMP2-derived epitope increase HLA/peptide complex stability and immunogenicity: implications for immunotherapy of Epstein–Barr virus-associated malignancies. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2579–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199908)29:08<2579::AID-IMMU2579>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masucci MG, Torsteindottir S, Colombani J, Brautbar C, Klein E, Klein G. Down-regulation of class I HLA antigens and of the Epstein–Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:4567–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.13.4567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masucci MG, Stam NJ, Torsteinsdottir S, Neefjes JJ, Klein G, Ploegh HL. Allele-specific down-regulation of MHC class I antigens in Burkitt lymphoma lines. Cell Immunol. 1989;120:396–400. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisan T, Zhang QJ, Levitskaya J, Coram M, Kurilla MG, Masucci MG. Defective presentation of MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic T-cell epitopes in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:251–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961009)68:2<251::AID-IJC19>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe M, Khanna R, Jacob CA, et al. Restoration of endogenous antigen processing in Burkitt's lymphoma cells by Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein-1: coordinate up-regulation of peptide transporters and HLA-class I antigen expression. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1374–84. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frisan T, Levitsky V, Polack A, Masucci MG. Phenotype-dependent differences in proteasome subunit composition and cleavage specificity in B cell lines. J Immunol. 1998;160:3281–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vinitsky A, Antón LC, Snyder HL, Orlowski M, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. The generation of MHC class I-associated peptides is only partially inhibited by proteasome inhibitors: involvement of nonproteasomal cytosolic proteases in antigen processing? J Immunol. 1997;159:554–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luckey CJ, King GM, Marto JA, et al. Proteasomes can either generate or destroy MHC class I epitopes: evidence for nonproteasomal epitope generation in the cytosol. J Immunol. 1998;161:112–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valmori D, Gileadi U, Servis C, Dunbar PR, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Cerundolo V, Lévy F. Modulation of proteasomal activity required for the generation of a cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined peptide derived from the tumor antigen MAGE-3. J Exp Med. 1999;189:895–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarz A, Beissert S, Grosse-Heitmeyer K, Gunzer M, Bluestone JA, Grabbe S, Schwarz T. Evidence for functional relevance of CTLA-4 in ultraviolet-radiation-induced tolerance. J Immunol. 2000;165:1824–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavioli R, Vertuani S, Masucci MG. Proteasome inhibitors reconstitute the presentation of cytotoxic T-cell epitopes in Epstein–Barr virus-associated tumors. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:532–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Y, Lutz CT. Interferon-gamma control of EBV-transformed B cells: a role for CD8+ T cells that poorly kill EBV-infected cells. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:213–25. doi: 10.1089/088282402317340350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daskalogianni C, Apcher S, Candeias MM, Naski N, Calvo F, Fåhraeus R. Gly-Ala repeats induce position- and substrate-specific regulation of 26 S proteasome-dependent partial processing. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30090–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803290200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawada J, Zou P, Mazitschek R, Bradner JE, Cohen JI. Tubacin kills Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-Burkitt lymphoma cells by inducing reactive oxygen species and EBV lymphoblastoid cells by inducing apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17102–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809090200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou P, Kawada J, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Bortezomib induces apoptosis of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed B cells and prolongs survival of mice inoculated with EBV-transformed B cells. J Virol. 2007;81:10029–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02241-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.