Abstract

Leucine-rich repeats (LRR) characterize a diverse array of proteins and function to provide a versatile framework for protein-protein interactions. Importantly, each of the bacterial LRR proteins that have been well described, including those of Listeria monocytogenes, Yersinia pestis, and Shigella flexneri, have been implicated in virulence. Here we describe an 87.4-kDa group A Streptococcus (GAS) protein (designated Slr, for streptococcal leucine-rich) containing 10 1/2 sequential units of a 22-amino-acid C-terminal LRR homologous to the LRR of the L. monocytogenes internalin family of proteins. In addition to the LRR domain, slr encodes a gram-positive signal secretion sequence characteristic of a lipoprotein and a putative N-terminal domain with a repeated histidine triad motif (HxxHxH). Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assays indicated that slr is transcribed abundantly in vitro in the exponential phase of growth. Flow cytometry confirmed that Slr was attached to the GAS cell surface. Western immunoblot analysis of sera obtained from 80 patients with invasive infections, noninvasive soft tissue infections, pharyngitis, and rheumatic fever indicated that Slr is produced in vivo. An isogenic mutant strain lacking slr was significantly less virulent in an intraperitoneal mouse model of GAS infection and was significantly more susceptible to phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. These studies characterize the first GAS LRR protein as an extracellular virulence factor that contributes to pathogenesis and may participate in evasion of the innate host defense.

The gram-positive pathogen group A Streptococcus (GAS) causes multiple human infections, ranging from mild pharyngitis to severe disease including toxic shock syndrome, necrotizing fasciitis, and rheumatic fever (14, 62). The pathogen is characterized by extensive allelic variation and produces a variety of virulence factors (39, 47, 61, 68, 70). An overall increase in the incidence of GAS disease since the 1980s, coupled with fears about the emergence of antibiotic resistance, has renewed interest in the mechanisms of pathogenesis and the development of new therapeutics (2, 71). While the molecular basis of GAS pathogenesis is not fully understood, it is known that the pathogen produces a large number of extracellular proteins, including several which mediate interactions with the host (3, 14, 23, 29-33, 47, 74). However, many of these extracellular products remain uncharacterized. To address this issue, we recently studied the genomes of four GAS strains (serotypes M1, M3, M5, and M18) with the goal of identifying genes that encode novel extracellular proteins (68). Among those identified was an 87.4-kDa protein (Spy1361) with an apparent signal secretion sequence. Absent from this protein was an LPXTG motif that covalently links gram-positive proteins to the cell surface. Our initial investigation revealed that the gene was conserved in 37 phylogenetically diverse strains and was expressed in vitro (68). In addition, preliminary Western immunoblot analysis of a small sample of human patient sera suggested that the protein was made during the course of invasive GAS infection (68). Finally, BLAST analysis indicated that the inferred amino acid sequence was homologous to those of members of the Listeria monocytogenes internalin protein family, a set of virulence factors characterized by a leucine-rich repeat (LRR). Taken together, the results of the initial study suggested that further investigation of this extracellular protein was warranted.

The LRR motif consists, on average, of 20 to 29 amino acid residues and contains an 11-residue segment with the consensus sequence LXXLXLXXN/CXL (X = any amino acid) (41, 42, 53). Valine, isoleucine, and phenylalanine have also been identified in the positions normally occupied by leucine. The LRR motif forms a structural unit consisting of a β strand and an α helix which occurs from 1 to 30 times in tandem arrays (42). The resulting horseshoe-shaped molecule provides a versatile scaffold for protein-protein interactions (42). A diverse array of functions have been described for LRR proteins, including RNase inhibition, GTPase activation, and virulence (7, 8, 35, 40, 44, 45). Bacterial LRR proteins have been identified in Yerisnia pestis, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and others (34, 49, 59). However, the largest known family of bacterial LRR proteins is found in Listeria spp.

The internalin multigene family of L. monocytogenes consists of 21 genes encoding proteins characterized by an N-terminal LRR (27). Nineteen of these genes, including inlA, encode proteins with an LPXTG amino acid motif that covalently links proteins made by gram-positive bacteria to the cell surface (27). The remaining genes encode proteins that are either secreted (e.g., InlC) or attached to the bacterial cell surface by another mechanism (e.g., InlB) (27). inlA and inlB, the most thoroughly studied members of the multigene family, are organized into an operon, and each is required for invasion of different nonphagocytic cell lines (reviewed in reference 6). Genetic inactivation of either inlA or inlB leads to a significant decrease in L. monocytogenes virulence (6).

Here we report the characterization of a GAS gene (designated slr, for streptococcal leucine-rich) encoding a protein containing 10 1/2 sequential repeats of a 22-amino-acid C-terminal LRR that is homologous to the LRR of the L. monocytogenes internalin protein family. Allelic replacement of slr results in significantly reduced virulence in mice after intraperitoneal challenge. Investigation of the mechanism for this reduction in virulence revealed that the isogenic mutant strain lacking slr was significantly more susceptible to phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Strain MGAS5005, a representative serotype M1T1 strain recently isolated from a case of invasive GAS disease, was the primary strain used for this investigation and was the parent strain for construction of an slr isogenic mutant (see below). A serotype M1T1 strain was chosen because population genetic analysis has indicated that M1T1 strains are among the most common causes of invasive GAS infections worldwide in most case studies (62). MGAS5005 has been extensively characterized in numerous investigations of GAS pathogenesis (reviewed in references 62 and 70).

slr sequence analysis.

Multiple-sequence alignment of nucleotide and inferred amino acid sequences was performed with CLUSTAL W (version 1.8) (77). Sequences from MGAS5005 and 11 additional strains representing 11 M protein serotypes (M2, M3, M4, M6, M12, M18, M22, M28, M49, M75, and M89) that commonly cause pharyngitis, rheumatic fever, skin infections, and invasive episodes were used (68). Analysis of nucleotide and amino acid polymorphisms was conducted by use of MEGA 2.1 (http://www.megasoftware.net/).

TaqMan real-time reverse transcriptase PCR analysis.

Strain MGAS5005 was grown in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with yeast extract (THY medium) (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. A 100-μl aliquot of the culture was added to each of six 50-ml aliquots of THY medium, incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2, and harvested at six time points (when A600 = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8) throughout the growth cycle. Total RNA was isolated at each time point as previously described (10).

TaqMan assays were performed with an ABI 7700 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Forest City, Calif.) and the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR master mix reagents kit (Applied Biosystems) as described by Chaussee et al. (10). The amplification profile used was as follows: 1 cycle at 48°C for 30 min, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The critical threshold cycle (Ct) is defined as the cycle at which fluorescence becomes detectable above background and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial concentration of template. A standard curve was plotted for each reaction with Ct values obtained from amplification of known quantities of genomic DNA isolated from strain MGAS5005. The standard curves were used to transform Ct values of the experimental samples into the relative number of DNA molecules. The quantity of cDNA for each experimental gene was normalized to the quantity of the constitutively transcribed control gene (gyrA) in each sample. Specific transcript levels were expressed as fold differences compared to transcript levels at the earliest time point measured (A600 = 0.05).

Gene cloning and expression of recombinant (6xHis) Slr.

slr was cloned from strain MGAS5005 with primers 5′-ACCATGGGTCAATCACGAGGTAATGGTAC-3′ and 5′-CGAATTCTTAGTCAGCATGGTTTTGCTC-3′. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and EcoRI and inserted into pET-His2 to yield recombinant plasmid pHis2-slr. The vector pET-His2 was obtained by inserting the smaller XbaI/EcoRI fragment of pET-His (GenBank accession no. L20317) (11) into pET-21b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) linearized by XbaI and EcoRI. The protein made by this clone had 12 amino acid residues, MHHHHHHLETMG, fused to the second amino acid residue (Q24) of the Slr protein. For assessment of protein production, a strain of recombinant Escherichia coli BL21 (Novagen) containing pHis2-slr was grown at 37°C in 10 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. Cultures were induced at an A600 of 0.5 with 0.1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and were grown overnight at 25°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, lysed, and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Western immunoblot analysis.

A 1:20 dilution of E. coli lysate containing recombinant protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, Mass.), and probed with patient sera. The sera studied included convalescent-phase sera collected from 9 patients with pharyngitis, paired acute- and convalescent-phase sera obtained from 27 patients with invasive GAS infections, paired acute- and convalescent-phase sera collected from 4 patients with superficial skin infections, and convalescent-phase sera obtained from 40 patients diagnosed with acute rheumatic fever (ARF). Convalescent-phase serum was collected approximately 3 weeks postdiagnosis. In some cases, sera obtained from patients with a history of ARF were collected several years after the last documented presentation of ARF symptoms.

Recombinant protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane with a Bio-Rad semidry transfer chamber (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) for 60 min at 15 V. Following transfer, the membrane was treated with a 5% (wt/vol) solution of dehydrated milk in blocking buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4] and 150 mM NaCl) for 1 h. Primary antibody (patient serum) was added to the blocking reagent, and the membrane was incubated for 1 h. Serum samples were used at a dilution of either 1:500 or 1:1,000, depending on the level of reactivity observed. Affinity-purified goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Bio-Rad) was used as the secondary antibody. Signal detection was conducted with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, Ill.).

Purification of recombinant Slr.

Recombinant Slr was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pHis2-slr. The bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in 6 liters of LB broth supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin per liter. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 70 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, and sonicated on ice for 15 min. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) column (2.5 × 10 cm). Slr was identified by SDS-PAGE and peak fractions were pooled. Protein concentration was measured with the modified Lowry protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology), with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Affinity-purified anti-Slr antibodies.

Purified recombinant Slr was supplied to Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, Tex.) for the production of purified antibodies. Rabbits were immunized and then boosted with 100 μg of antigen every 2 weeks for 2 months and then were boosted once a month. The animals were bled every 2 weeks starting after the 3rd immunization (5 weeks). Hyperimmune sera were then passed over an Slr-agarose column to capture antibodies specific for the protein.

Detection of Slr on the GAS cell surface.

Surface localization of Slr was analyzed with a FACScaliber flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif.) using affinity-purified Slr-specific antibodies. Purified rabbit IgG raised against an irrelevant protein antigen was used as a control for nonspecific antibody binding. Briefly, GAS strain MGAS5005 was grown to exponential phase (A600 = 0.4) in THY medium, harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), pH 7.2, and resuspended in DPBS at 108 CFU/ml. Anti-Slr antibody was added to 100 μl of bacterial suspension at a final concentration of 0.05 μg/100 μl and incubated for 30 min on ice. Samples were washed with stain buffer (BD Biosciences) and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) (1:500 dilution) for 30 min on ice prior to flow cytometry.

Allelic replacement of slr.

The slr gene was replaced in MGAS5005 with a spectinomycin resistance cassette designated spc2 (51) which contains a 5′ consensus ribosome-binding site (GGAGG) followed by a promoterless copy of the aad gene. The vector used for allelic replacement of slr (pSRSlr) was constructed in three steps (Fig. 1A) from pFW14, a plasmid that cannot replicate in GAS (65). First, a fragment consisting of 581 bp directly upstream of the slr start codon was amplified by PCR from MGAS5005 with primers designed to introduce a 5′ SwaI site (5′-ATGGACATTTAAATACCACCGGTGCTAGTCGA-3′) and a 3′ XmaI site (5′-ATTCAACCCGGGTTTTTATTTAACTGGTTAAG-3′). The amplicon was digested (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and inserted into the SwaI-XmaI sites of vector pFW14, generating pSlr5. Next, a fragment consisting of 550 bp located 5 bp downstream of the slr stop codon was amplified with primers designed to introduce a 5′ NaeI site (5′-GAATAAGCCGGCCCAACTGAATCGTCCTAATG-3′) and a 3′ AvrII site (5′-CTTCAGCCTAGGACTCAGACGTGAAAAGTTTA-3′). The amplicon was cloned into the NaeI-AvrII sites of pSlr5, generating pSlr53. Finally, spc2 was inserted into the SmaI site of pSlr53, yielding the suicide plasmid pSRSlr.

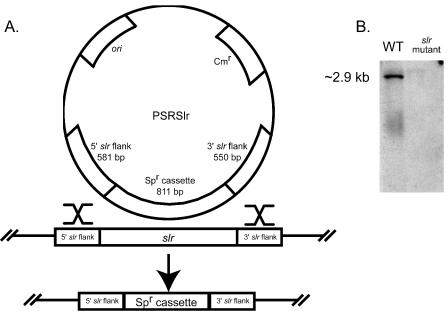

FIG. 1.

Construction of the plasmid pSRSlr and allelic replacement of slr. (A) pSRslr has a ColE1 origin of replication and carries a gene for chloramphenicol resistance. The sequence of the spc2 cassette encoding spectinomycin resistance (Spr) is cccgggtgactaaatagtgaggaggatatat-TTG-aad-TAA-aaaggaggaaaatcacatggcccggg. (B) Southern blot analysis of the genomic DNA isolated from MGAS5005 (wild type [WT]) and the isogenic mutant strain lacking slr. DNA was digested with SpeI and SacI, generating an ∼2,900-kb fragment containing slr. As expected, a probe generated from a 419-bp internal fragment of slr (nucleotides 626 to 1044) hybridized only to the wild-type DNA.

Electrocompetent cells made from MGAS5005 were electroporated with pSRSlr (0.1-cm gap, 400 Ω, 25 μF, 1.8 kV). Transformants were selected on THY plates supplemented with 150 μg of spectinomycin per ml, and resistant colonies were screened by PCR for the absence of slr. Southern hybridization was used to confirm the absence of slr. Briefly, genomic DNA was digested with SacI and SpeI, generating an ∼2,900-kb fragment containing slr. Primers SlrP3 (5′-TGCATTTCCCAACCTCAGAT-3′) and SlrP4 (5′-TTCACGGGCATGCTCAATAG-3′) were used to generate an internal 419-bp probe (nucleotides 626 to 1044 of slr). Nucleotide sequencing of 286 bp upstream of the cassette, spc2, and 153 bp downstream of the cassette did not reveal the introduction of spurious mutations.

The amount of hyaluronic acid capsule produced by the wild-type and mutant strains was determined to ensure that genetic manipulation did not result in a capsule-deficient mutant. Briefly, 10 ml of exponential-phase culture was harvested, washed twice with water, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of water. Capsules were extracted by the addition of 1 ml of chloroform and vigorous shaking (82). The aqueous phase was added to a 2-ml solution consisting of 20 mg of Stains-all {1-ethyl-2-[3-(1-ethylnaphtho-[1,2-d]thiazolin-2-ylidene)-2-methylpropenyl]naphtha-[1,2-d]thiazolium bromide} (Sigma) and 60 μl of glacial acetic acid in 100 ml of 50% formamide (82). The absorbance was measured at A640, and the values were compared to a standard curve generated from known concentrations of Streptococcus zooepidemicus hyaluronic acid (Sigma).

Mouse infection studies.

The virulence of wild-type strain MGAS5005 and the isogenic mutant strain lacking slr was compared in a bacteremia model of mouse infection as previously described (38). Experimental animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Rocky Mountain Laboratories Animal Care and Usage Committee. Bacteria were harvested at an A600 of ∼0.6 to coincide with maximal expression of slr (see below). Cells were washed with sterile, pyrogen-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the A600 was adjusted to yield an inoculum of ∼5 × 107 CFU (0.2 ml). Two groups of 12 female outbred CD-1 Swiss mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were inoculated intraperitoneally with the wild-type or isogenic mutant strain. Mice were monitored for 75 h, mortality was recorded, and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted (JMP statistical software). The mortality rate was examined for statistical significance by use of log-rank and Wilcoxon tests.

Phagocytosis assays.

Phagocytosis of MGAS5005 and the slr isogenic mutant by human PMNs was analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described (81). GAS was grown to exponential phase, washed, and resuspended in DPBS at 109/ml. Bacteria were labeled with 5.0 μg of fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml for 20 min at 37°C and then washed three times in RPMI 1640 buffered with 10 mM HEPES (RPMI/H) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Labeled GAS was opsonized in 50% normal human serum for 30 min at 37°C, resuspended in RPMI/H at 108/ml, and chilled on ice until used. PMNs (106) were combined with opsonized GAS (∼107) in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate and centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C to synchronize phagocytosis. Samples were analyzed immediately (0 min) or placed in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 for 30 min. After measuring the number of PMNs with bound and ingested GAS, samples were quenched by 2.5 volumes of trypan blue (2 mg/ml in 0.15 M NaCl-0.02 M citrate buffer, pH 4.4) to determine the percentage of PMNs with ingested GAS. A single gate was used to analyze PMNs (Cell Quest Software; BD Biosciences), and the threshold was set to exclude unbound bacteria. Percent phagocytosis was determined by the percentage of fluorescein isothiocyanate-positive PMNs after quenching with trypan blue.

RESULTS

slr encodes a C-terminal LRR and a repeated N-terminal HxxHxH motif.

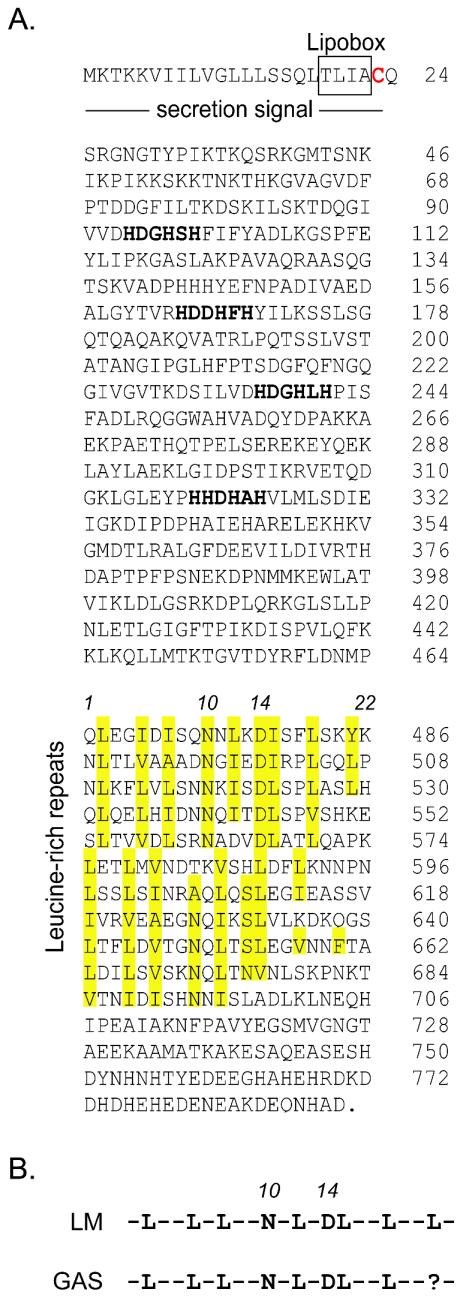

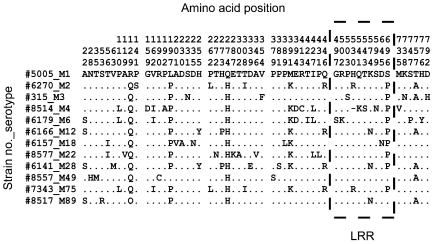

In a previous study that focused on the identification of novel extracellular proteins of GAS, a 2,379-bp gene (spy1361, referred to here as slr) was identified that encoded a gram-positive signal secretion sequence and shared homology with several members of the internalin family of virulence genes of L. monocytogenes (68). Given the important role of at least two of the internalin proteins in L. monocytogenes virulence (12), we sought to identify putative structural similarities encoded by slr. Multiple-sequence alignment of Slr from 12 GAS strains representing 12 M serotypes identified a 22-amino-acid LRR in the C-terminal half of the molecule (Fig. 2A.). The LRR occurs 10 1/2 times in tandem and closely resembles the consensus motif of the internalin LRR (Fig. 2B) (42, 53, 54). After the first five tandem units, the conserved residues of the LRR are moved back by one position, corresponding in size to the deletion of a single amino acid. Hence, the leucines and isoleucines occupying positions 2, 5, 7, 12, 15, and 18 in the first five LRRs occupy positions 1, 4, 6, 11, 14, and 17 in the following five tandem repeats (Fig. 2A). Similar to listerial internalins, a conserved asparagine is located at position 10 or 9, forming the Asn ladder (53). Characteristic of InlB, position 14 or 13 contains Asp, Ser, or Asn, and primarily small amino acids are located at position 17 or 16 (53). Importantly, sequence variation does not occur at conserved positions of the Slr LRR in the strains examined (Fig. 3). Unlike in members of the internalin family, the Slr LRR is located in the C-terminal half of the molecule.

FIG. 2.

Characteristics of the amino acid sequence of Slr. (A) The putative gram-positive signal secretion sequence is underlined. The four-amino-acid lipobox characteristic of secreted lipoproteins is indicated by a box. The putative lipidated cysteine, shown in red, marks the start of the mature form of the protein. Four histidine triad motifs (HxxHxH) are shown in bold. The 10 sequential repeats of a 22-amino-acid C-terminal LRR occupying positions 465 to 695 of the inferred amino acid sequence are indicated. Conserved positions of the LRR are highlighted in yellow. Position numbers 1, 10, 14, and 22 are provided for reference. Consistent with the LRR of L. monocytogenes InlB, position 10 is an Asn or Gln (Asn ladder) and position 14 is an Asp, Ser, or Asn. (B) GAS LRR consensus motif compared to that identified in L. monocytogenes (LM).

FIG. 3.

Polymorphic amino acid sites identified in the multiple-sequence alignment of the inferred amino acid sequence of Slr from 12 representative GAS M serotypes. Amino acid positions are listed vertically across the top of the alignment, while the strain numbers and corresponding serotypes are presented on the left. For purposes of comparison, strain MGAS5005_M1 is listed as the consensus sequence. Only polymorphic amino acid sites are listed. For example, 5005_M1 has an “A” at position 22 while four other strains possess an “S” at this position. Dots indicate that the residues agree with the consensus sequence. Ten polymorphic sites, highlighted by the dashed box, were identified within the LRR. However, none of the conserved positions making up the LRR motif shown in Fig. 1 are polymorphic. The four histidine triad motifs are also conserved in the strains examined.

Further examination of the inferred amino acid sequence of Slr identified a histidine triad motif (HxxHxH) that is present four times in the N-terminal half of the molecule (Fig. 2A). The same motif was recently identified in four surface proteins of Streptococcus pneumoniae, although a function was not described (1). The HxxHxH motif has not been identified in the L. monocytogenes internalin family.

TaqMan analysis of gene transcription.

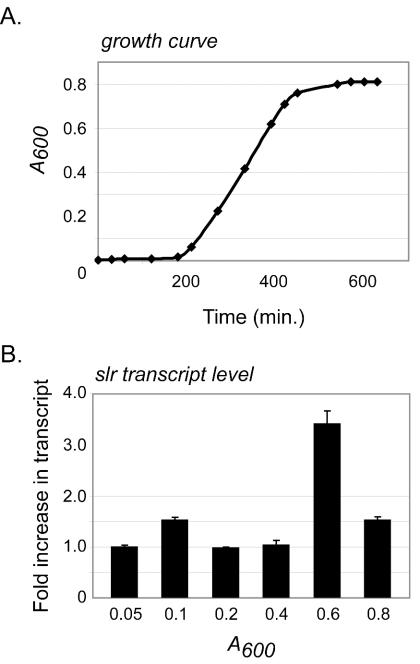

Previous studies have indicated that expression of GAS genes can vary throughout growth and that many important virulence factors are maximally expressed during the exponential phase (10, 56, 66, 69). To gain insight into slr gene regulation, TaqMan assays were performed to study the expression of slr in vitro in MGAS5005. Bacteria were harvested at six time points (when A600 = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8) throughout the growth cycle, and total RNA was isolated (Fig. 4A). slr was expressed at all time points examined, with the maximal level of gene transcript attained during the exponential phase of growth (A600 = 0.6) (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

TaqMan analysis of slr gene transcription. (A) Growth curve of GAS strain MGAS5005 in THY medium, incubated at 37°C (5% CO2). Total RNA was isolated at six time points (when A600 = 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8) throughout the growth cycle. (B) Transcription level expressed as the fold increase in slr transcripts compared to the transcript level at an A600 of 0.05. The data represent values obtained with two independently isolated RNA samples analyzed in triplicate. All measurements were normalized to the gyrA transcript as described in Materials and Methods.

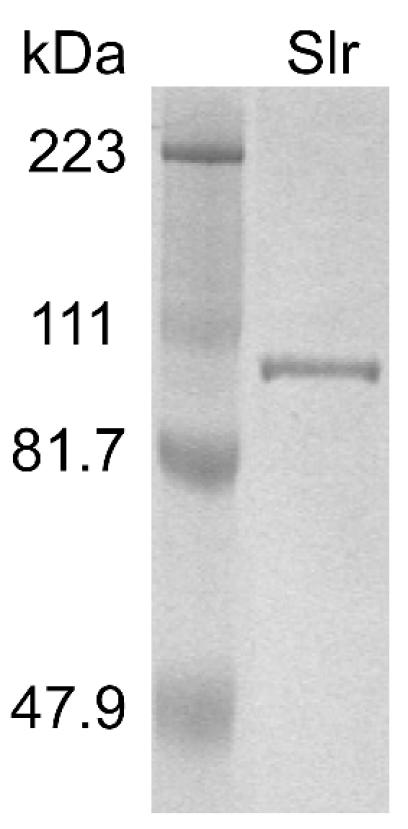

Recombinant Slr protein.

To facilitate production and purification of recombinant Slr protein, we cloned a fragment of the slr gene that would encode amino acid residues Q24 to D770. This fragment was cloned to avoid potential toxicity associated with the secretion signal and a negatively charged region located at the carboxy terminus. The recombinant protein has a 12-amino-acid N-terminal tag (MHHHHHHLETMG) fused to Q24 of the Slr protein. The recombinant protein was overexpressed in soluble form in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE gel showing purified recombinant (6xHis) Slr. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, molecular mass marker; lane 2, 3 μg of purified recombinant Slr.

Slr is present on the cell surface of GAS.

Certain characteristics of the Slr signal secretion sequence suggested that the molecule was a lipoprotein. Bacterial lipoproteins possess a well-defined signal peptide that consists of an n domain containing the charged amino acids arginine or lysine, a hydrophobic region (the h domain), and a cleavage domain containing the lipobox (reviewed in reference 75). Specifically, the Slr signal peptide consists of a 5-residue charged n region followed by a 13-residue hydrophobic h region and a characteristic lipobox preceding a cysteine residue (Fig. 2A). To determine if Slr is present on the GAS cell surface, strain MGAS5005 was grown to exponential phase, harvested, stained with Slr-specific antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The ability of anti-Slr antibody to bind to GAS was demonstrated by a substantial shift in fluorescence over that of control antibody, indicating that Slr is present on the GAS cell surface (Fig. 6A). Western immunoblot analysis of MGAS5005 culture supernatant collected at the same time did not indicate the presence of Slr (data not shown).

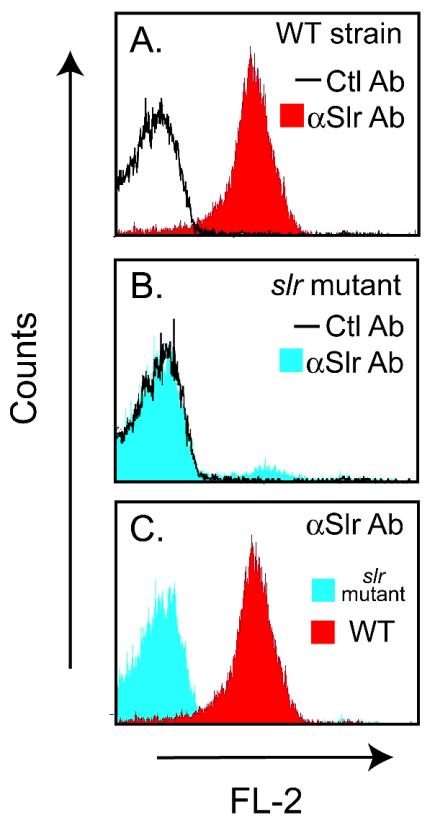

FIG. 6.

Cell surface localization of Slr. (A) Strain MGAS5005 was incubated with a control antibody (Ctl Ab; black line) or anti-Slr antibody (αSlr Ab; red histogram). (B) The slr mutant GAS strain was incubated with a control antibody (Ctl Ab; black line) or anti-Slr antibody (αSlr Ab; blue histogram). (C) Comparison of the MGAS5005 wild-type (red histogram) and slr mutant (blue histogram) GAS strains stained with anti-Slr antibody. Results are representative of two separate experiments.

Reactivity of human sera with recombinant proteins.

Our earlier data (68) suggested that Slr was produced in humans infected with GAS. However, the study was limited to the Western immunoblot analysis of sera collected from four patients with invasive GAS infections and from seven healthy individuals. Therefore, it is unknown if Slr is produced during multiple GAS infection types or if its synthesis is confined to a single manifestation of GAS disease. To seek evidence of Slr-specific antibody production in response to different GAS infections, Western immunoblot analysis was conducted with paired acute- and convalescent-phase sera collected from 27 patients with invasive GAS infections (culture positive from a normally sterile site) and from 4 patients with superficial skin infections (noninvasive).The infecting strains represented 19 distinct serotypes (M1, M3.2, M5.8193b, M11, M12, M13w, M22.2, M28, M36, M44/61, M58, M75, M89, emm102, emm114, st833.1, st2917, st3757, and st6735). Slr was reactive with antibodies present in 67% of convalescent-phase sera collected from invasive episodes and 50% of convalescent-phase sera from patients with superficial skin infections. Reactivity was not observed with acute-phase serum samples, indicating recent exposure to Slr (Fig. 7).

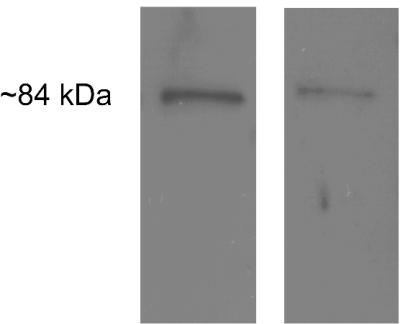

FIG. 7.

Western immunoblot showing the typical reactivity of convalescent-phase serum samples with recombinant Slr. A 1:20 dilution of E. coli lysate containing recombinant Slr and a 1:500 (left) or 1:1,000 (right) dilution of patient serum was used. Reactivity was not observed with acute-phase serum samples under the above conditions.

Since the complement of genes expressed during GAS pharyngitis or infections leading to ARF may differ from that during invasive infections, Western immunoblot analysis of convalescent-phase sera obtained from 9 patients with recent pharyngitis and 40 individuals with a history of ARF was conducted. The serologic reactivities among these 49 patients were closely similar to those among 31 subjects with invasive or superficial skin infections. Slr reacted with 56% of sera obtained after episodes of pharyngitis and with 70% of sera obtained from individuals with ARF. Taken together, these results indicate that Slr is produced during the course of multiple GAS infection types.

Allelic replacement of the slr gene in a serotype M1 GAS strain.

To facilitate investigation of the role of Slr in host-pathogen interactions, we generated an isogenic mutant strain lacking slr from MGAS5005. Sequencing analysis indicated that recombination had occurred 3 bp upstream and 25 bp downstream of slr, resulting in the replacement of slr with the spc2 spectinomycin resistance cassette (cccgggtgactaaatagtgaggaggatatat-TTG-aad-TAA-aaaggaggaaaatcacatggcccgggcgccggccca, where capital letters represent start and stop codons and italicized letters represent a gene conferring spectinomycin resistance). Polar effects were not anticipated, given that the next closest open reading frame in the M1 genome is located 536 bp downstream of the site of recombination and that the spc2 cassette lacks a promoter. Southern hybridization with a probe generated from a 419-bp internal fragment of slr confirmed the absence of slr (Fig. 1B). Flow cytometry analysis did not detect the presence of Slr on the surface of the mutant strain (Fig. 6B and C). In addition, the slr transcript was not detected in TaqMan assays (data not shown).

Hyaluronic acid capsule production was unchanged in the mutant strain in vitro. Ten milliliters of culture containing 2.5 × 109 CFU of the slr mutant per ml produced 8 μg of hyaluronate compared to 7.2 μg produced by 10 ml of MGAS5005 (1.9 × 109 CFU/ml).

Slr contributes to virulence in mice.

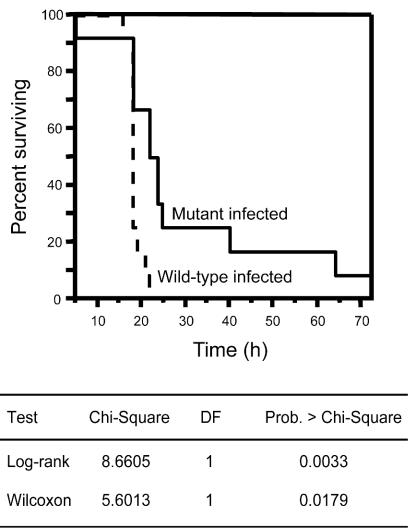

To investigate if the absence of Slr has an effect on GAS virulence, we compared the ability of the wild-type and mutant strains to cause mouse mortality following intraperitoneal inoculation. Mice received an inoculum of ∼5 × 107 CFU of GAS, an amount previously shown to result in the death of >90% of the animals tested (52). The rate of mortality was significantly reduced in mice injected with the mutant strain (log-rank test, P = 0.003; Wilcoxon test, P = 0.02) (Fig. 8). Thus, Slr is required for full GAS virulence under the conditions tested.

FIG. 8.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the relative rates of mouse mortality caused by wild-type (dashed line) and isogenic slr-inactivated mutant (solid line) strains. Two groups of 12 female CD-1 Swiss mice were challenged intraperitoneally with ∼5.0 × 107 CFU (0.2 ml) of the wild-type or slr mutant strain. A significant difference in the rates of mouse mortality was observed based on two statistical tests (log-rank and Wilcoxon tests). DF, degrees of freedom.

Absence of slr results in increased phagocytosis by human PMNs.

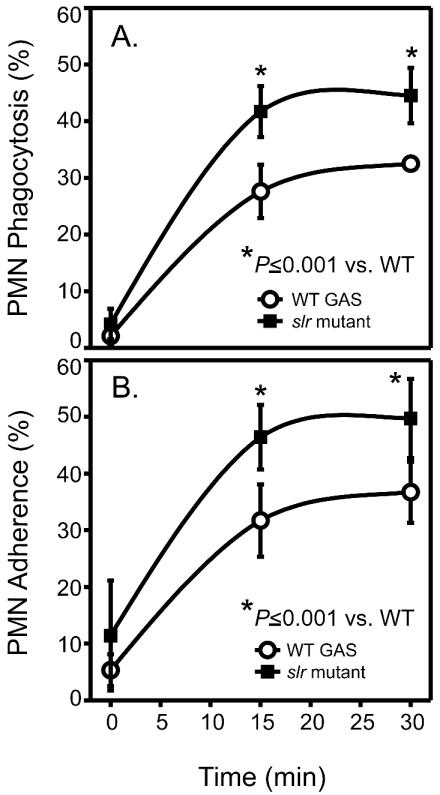

Host clearance of GAS from the bloodstream or infected tissues is primarily mediated by professional phagocytes; however, several GAS extracellular products have been demonstrated to interfere with this process (24, 36, 63, 82). Given the significant reduction in the mortality rate of mice challenged with an isogenic slr mutant strain, we sought to determine whether the lack of slr expression altered phagocytosis of opsonized GAS in serum by human PMNs. There was a significant increase in adherence and phagocytosis of the isogenic slr mutant GAS strain by human PMNs compared with the wild-type strain (P ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 9). Therefore, increased PMN phagocytosis of the mutant strain likely reflected greater adherence. Importantly, these data suggest that Slr contributes to virulence in human GAS infections.

FIG. 9.

Phagocytosis of a parental serotype M1 strain and an isogenic mutant strain lacking slr. Human PMNs were incubated with fluorescently labeled and opsonized MGAS5005 (open circles) or the slr mutant (black squares), and the amounts of phagocytosis (A) and ingested and bound bacteria (B) were determined at the indicated times by flow cytometry. Results are the means ± standard deviations from five separate experiments. Phagocytosis of the mutant strain by human PMNs and the number of adherent mutant bacteria were significantly higher than for the wild-type strain (for panel A, P ≤ 0.001; for panel B, P ≤ 0.001).

DISCUSSION

The large number of LRR structures that have been described, specifically the crystal structures of InlA, InlB, and YopM (20, 54, 72, 73), allow us to make predictions about the structure of the Slr LRR domain. Indeed, Kajava and Kobe have recently assessed their ability to model LRR proteins and found such modeling to be reliable (37). The Slr LRR domain is likely to form a curved solenoid, with the conserved leucines and isoleucines (Fig. 2B, positions 2, 5, 7, 12, and 18) forming a hydrophobic core (54, 72, 73). Consistent with other bacterial LRR proteins, one would expect the conserved asparagine at position 10 to hydrogen bond with other residues of the LRR, forming a structural ladder (20, 54, 72, 73). The conserved aspartate at position 14 may also hydrogen bond to other LRR residues, as in InlB (54), or it may be exposed to the environment for involvement in protein-protein interactions, as predicted for YopM (37). The exact function of YopM has yet to be elucidated, but it is clear that InlA and InlB participate in the intracellular invasion of L. monocytogenes and that the LRR domain is necessary for this function (7, 44). The similarity between the LRR of Slr and those of InlA and InlB leads one to hypothesize that Slr might play a role in GAS intracellular invasion. GAS functions primarily as an extracellular pathogen, but invasion of several cell types has been documented (15, 16, 25, 28, 43, 57, 60), and entry may provide a means for the organism to escape antibiotic therapy, reach deeper tissues, or achieve an asymptomatic carrier state (13, 21). One proposed model of GAS invasion suggests that cell entry is achieved by a zipper-like mechanism analogous to that of L. monocytogenes and Y. pestis (13). An as yet unidentified adhesin (possibly Slr) would mediate close contact of GAS to epithelial cells, allowing a GAS invasin (presumably M protein or a fibronectin binding protein) to interact with the extracellular matrix and to induce internalization (13). Importantly, our data indicate that GAS is more susceptible to PMN adherence and phagocytosis in the absence of Slr (see below). However, since interactions with phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells may differ, experiments are under way to investigate the hypothesized association between Slr and intracellular invasion.

As mentioned previously, 19 of the known internalin proteins are putatively anchored to the L. monocytogenes cell surface by an LPXTG motif, 1 is associated with the cell surface via GW domains, and 1 is secreted (27). Slr lacks an LPXTG motif and GW domains. However, the gram-positive signal peptide of Slr contains features commonly associated with a lipoprotein (75, 76), and our data clearly demonstrate that Slr is localized to the GAS cell surface (Fig. 6). Presumably, an N-acyl diglyceride group is thioether linked to the first residue of the mature Slr protein (a cysteine), and this lipid serves to orient the protein by anchoring the amino terminus to the membrane long-chain fatty acids. This suggests that the C-terminal LRR of Slr is fully exposed on the bacterial cell surface, similar to the N-terminal LRR of internalins, which are anchored by the carboxy terminus. Hence, the availability of the LRR to interact with the host environment is achieved for both organisms, but by different methods.

Another putative structural feature of Slr is encoded by a HxxHxH motif which is repeated four times in the N-terminal half of the molecule. An identical motif in four proteins of S. pneumoniae (PhtA, PhtB, PhtD, and PhtE) was recently described by Adamou et al. (1). Each protein contained five (PhtA, PhtB, and PhtD) or six (PhtE) HxxHxH repeats. Like Slr, PhtA, PhtB, PhtD, and PhtE have signal secretion sequences characteristic of lipoproteins, including a lipobox preceding a putative lipidated cysteine. Active immunization of mice with recombinant PhtA, PhtB, and PhtD or passive immunization with rabbit hyperimmune serum raised against PhtA conferred protection against pneumococcal sepsis in a mouse model of infection (1). Similar results were reported by a separate group for their investigation of S. pneumoniae histidine protein A (PhpA), a HxxHxH protein with ∼76 to 85% sequence identity to PhtA, -B, and -D (83). Both parenteral and intranasal immunization of mice with a 79-kDa recombinant form of PhpA conferred protection against bacteremia following intranasal challenge (83). In addition to the identification of the HxxHxH repeats, several observations suggest that investigation of the potential of Slr for use in future vaccine-related studies is warranted. First, our original investigation reported that the gene encoding Slr was largely conserved among 37 strains representing the breadth of GAS population diversity (68). Thus, a protective immune response to Slr may protect against heterologous challenge. Second, Slr was detected on the cell surface of GAS, and Western immunoblot results indicated that Slr is produced in infected hosts. Third, our isogenic mutant strain lacking slr exhibited a significant reduction in host mortality rate (see below), suggesting that immune-mediated inhibition of Slr may be therapeutic.

The function of the HxxHxH repeats in Slr has yet to be elucidated. Histidine motifs, albeit not identical to the repeat identified here, have been implicated in the binding of divalent metal cations, particularly zinc, and are functionally important in numerous enzymes (9, 50, 64, 79, 80). Thus, an enzymatic function for Slr cannot be ruled out. Alternatively, metal cations may be structurally important for Slr or may form a bridge between Slr and its receptor. The crystal structure of InlB revealed the presence of two bound, yet highly exposed, calcium ions (54). Calcium is not required for the formation of InlB structure, but the ions were hypothesized to form a metal bridge between InlB and a host surface receptor (54). Similarly, integrins contain a metal ion-dependent adhesion site through which bound magnesium or manganese is believed to form a metal bridge with an integrin ligand (46).

Importantly, each of the prokaryotic LRR proteins that have been well described contributes to virulence. Analysis of three S. enterica serovar Typhimurium effector proteins (SlrP, SspH1, and SspH2) with LRRs revealed that genetic inactivation of slrP or allelic replacement in sspH1 and sspH2 resulted in decreased virulence in mice and calves, respectively (59, 78). Similarly, insertional inactivation of Y. pestis yopM, a putative activator of protein kinases RSK1 and PRK2 (55), led to greatly reduced virulence in a mouse model of infection (50% lethal dose, 3.4 × 105 versus 42 CFU) (48). Deletion of S. flexneri ipaH7.8, one of five ipaH gene copies encoding LRRs, delayed S. flexneri escape from mouse and human endocytic vacuoles (22). Extensive research has defined roles of InlA and InlB in virulence (5, 7, 8, 12, 17, 18, 26, 44, 45, 58), and deletion of inlC and inlGHE led to decreased L. monocytogenes virulence in a mouse model (19) and reduced bacterial loads in the livers of infected mice (67), respectively. In addition, recent evidence indicates that InlC and InlGHE are necessary for InlA-dependent invasion of nonphagocytic mammalian cells (4). To test the hypothesis that Slr contributes to GAS virulence, we constructed an isogenic mutant strain lacking the slr gene and tested it in a mouse model of GAS pathogenesis. We observed a significant reduction in the rate of mortality of mice challenged with the mutant strain (log-rank test, P = 0.003; Wilcoxon test, P = 0.02), with 25% of the mice surviving up to 40 h postinfection. All of the mice that were challenged with the wild-type strain died within 22 h. Given these results, evidence was sought for a role for Slr in human infections by examining GAS interaction with PMNs. A significant increase in the phagocytosis of the mutant strain was noted (P ≤ 0.001). The increase in phagocytosis of the slr mutant strain is likely a result of the observed increase in adherence to PMNs. Thus, Slr may act to inhibit adherence to human neutrophils and participate with other GAS virulence factors, such as M protein, in circumventing the host innate defense.

In summary, we have described a new virulence determinant of GAS characterized by an LRR domain that is likely involved in the mediation of pathogen-host interactions. Slr is made during the course of multiple GAS infection types and is required for full virulence of the organism. The absence of Slr leads to a significant increase in adherence to and phagocytosis by human PMNs. Thus, while the homology of the Slr LRR domain to the internalin protein family LRR, suggesting a role for Slr in intracellular invasion, should be investigated, current evidence indicates that Slr may participate in evading the host innate defense.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert L. Cole for technical assistance; D. Low, H. Hill, and L. G. Veasy for generously providing sera; and T. G. Schwan and N. P. Hoe for critical reading of the manuscript.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamou, J. E., J. H. Heinrichs, A. L. Erwin, W. Walsh, T. Gayle, M. Dormitzer, R. Dagan, Y. A. Brewah, P. Barren, R. Lathigra, S. Langermann, S. Koenig, and S. Johnson. 2001. Identification and characterization of a novel family of pneumococcal proteins that are protective against sepsis. Infect. Immun. 69:949-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alos, J. I., B. Aracil, J. Oteo, and J. L. Gomez-Garces. 2003. Significant increase in the prevalence of erythromycin-resistant, clindamycin- and miocamycin-susceptible (M phenotype) Streptococcus pyogenes in Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:333-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beres, S. B., G. L. Sylva, K. D. Barbian, B. Lei, J. S. Hoff, N. D. Mammarella, M. Y. Liu, J. C. Smoot, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, D. S. Campbell, T. M. Smith, J. K. McCormick, D. Y. Leung, P. M. Schlievert, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence of a serotype M3 strain of group A Streptococcus: phage-encoded toxins, the high-virulence phenotype, and clone emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10078-10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergmann, B., D. Raffelsbauer, M. Kuhn, M. Goetz, S. Hom, and W. Goebel. 2002. InlA- but not InlB-mediated internalization of Listeria monocytogenes by non-phagocytic mammalian cells needs the support of other internalins. Mol. Microbiol. 43:557-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bierne, H., and P. Cossart. 2002. InlB, a surface protein of Listeria monocytogenes that behaves as an invasin and a growth factor. J. Cell Sci. 115:3357-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braun, L., and P. Cossart. 2000. Interactions between Listeria monocytogenes and host mammalian cells. Microbes Infect. 2:803-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, L., F. Nato, B. Payrastre, J. C. Mazie, and P. Cossart. 1999. The 213-amino-acid leucine-rich repeat region of the Listeria monocytogenes InlB protein is sufficient for entry into mammalian cells, stimulation of PI 3-kinase and membrane ruffling. Mol. Microbiol. 34:10-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, L., H. Ohayon, and P. Cossart. 1998. The InIB protein of Listeria monocytogenes is sufficient to promote entry into mammalian cells. Mol. Microbiol. 27:1077-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner, C. 2002. Hint, Fhit, and GalT: function, structure, evolution, and mechanism of three branches of the histidine triad superfamily of nucleotide hydrolases and transferases. Biochemistry 41:9003-9014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaussee, M. S., R. O. Watson, J. C. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, B. P. C., and T. Hai. 1994. Expression vectors for affinity purification and radiolabeling of proteins using Escherichia coli as host. Gene 139:73-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cossart, P., J. Pizarro-Cerda, and M. Lecuit. 2003. Invasion of mammalian cells by Listeria monocytogenes: functional mimicry to subvert cellular functions. Trends Cell Biol. 13:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cue, D., P. E. Dombeck, and P. P. Cleary. 2000. Intracellular invasion by Streptococcus pyogenes: invasins, host receptors, and relevance to human disease, p. 27-33. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cywes, C., and M. R. Wessels. 2001. Group A Streptococcus tissue invasion by CD44-mediated cell signalling. Nature 414:648-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dombek, P. E., D. Cue, J. Sedgewick, H. Lam, S. Ruschkowski, B. B. Finlay, and P. P. Cleary. 1999. High-frequency intracellular invasion of epithelial cells by serotype M1 group A streptococci: M1 protein-mediated invasion and cytoskeletal rearrangements. Mol. Microbiol. 31:859-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dramsi, S., I. Biswas, E. Maguin, L. Braun, P. Mastroeni, and P. Cossart. 1995. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of InlB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol. Microbiol. 16:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dramsi, S., C. Kocks, C. Forestier, and P. Cossart. 1993. Internalin-mediated invasion of epithelial cells by Listeria monocytogenes is regulated by the bacterial growth state, temperature and the pleiotropic activator prfA. Mol. Microbiol. 9:931-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelbrecht, F., S. K. Chun, C. Ochs, J. Hess, F. Lottspeich, W. Goebel, and Z. Sokolovic. 1996. A new PrfA-regulated gene of Listeria monocytogenes encoding a small, secreted protein which belongs to the family of internalins. Mol. Microbiol. 21:823-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evdokimov, A. G., D. E. Anderson, K. M. Routzahn, and D. S. Waugh. 2001. Unusual molecular architecture of the Yersinia pestis cytotoxin YopM: a leucine-rich repeat protein with the shortest repeating unit. J. Mol. Biol. 312:807-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Facinelli, B., C. Spinaci, G. Magi, E. Giovanetti, and P. E. Varaldo. 2001. Association between erythromycin resistance and ability to enter human respiratory cells in group A streptococci. Lancet 358:30-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Prada, C. M., D. L. Hoover, B. D. Tall, A. B. Hartman, J. Kopelowitz, and M. M. Venkatesan. 2000. Shigella flexneri IpaH(7.8) facilitates escape of virulent bacteria from the endocytic vacuoles of mouse and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 68:3608-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischetti, V. A., E. C. Gotschlich, G. Siviglia, and J. B. Zabriskie. 1977. Streptococcal M protein: an antiphagocytic molecule assembled on the cell wall. J. Infect. Dis. 136(Suppl.):S222-S233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fluckiger, U., K. F. Jones, and V. A. Fischetti. 1998. Immunoglobulins to group A streptococcal surface molecules decrease adherence to and invasion of human pharyngeal cells. Infect. Immun. 66:974-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaillard, J. L., P. Berche, C. Frehel, E. Gouin, and P. Cossart. 1991. Entry of L. monocytogenes into cells is mediated by internalin, a repeat protein reminiscent of surface antigens from gram-positive cocci. Cell 65:1127-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greco, R., L. De Martino, G. Donnarumma, M. P. Conte, L. Seganti, and P. Valenti. 1995. Invasion of cultured human cells by Streptococcus pyogenes. Res. Microbiol. 146:551-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halbert, S. P. 1958. The use of precipitin analysis in agar for the study of human streptococcal infections. III. The purification of some of the antigens detected by these methods. J. Exp. Med. 108:385-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbert, S. P., and T. Auerbach. 1960. The use of precipitin analysis in agar for the study of human streptococcal infections. IV. Further observations on the purification of group A extracellular antigens. J. Exp. Med. 113:131-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halbert, S. P., and S. L. Keatinge. 1961. The analysis of streptococcal infections. VI. Immunoelectrophoretic observations on extracellular antigens detectable with human antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 113:1013-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halbert, S. P., L. Swick, and C. Sonn. 1955. The use of precipitin analysis in agar for the study of human streptococcal infections. I. Oudin technic. J. Exp. Med. 101:539-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halbert, S. P., L. Swick, and C. Sonn. 1955. The use of precipitin analysis in agar for the study of human streptococcal infections. II. Ouchterlony and Oakley techniques. J. Exp. Med. 101:557-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartman, A. B., M. Venkatesan, E. V. Oaks, and J. M. Buysse. 1990. Sequence and molecular characterization of a multicopy invasion plasmid antigen gene, ipaH, of Shigella flexneri. J. Bacteriol. 172:1905-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillig, R. C., L. Renault, I. R. Vetter, T. T. Drell, A. Wittinghofer, and J. Becker. 1999. The crystal structure of rna1p: a new fold for a GTPase-activating protein. Mol. Cell 3:781-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoe, N. P., R. M. Ireland, F. R. DeLeo, B. B. Gowen, D. W. Dorward, J. M. Voyich, M. Liu, E. H. Burns, Jr., D. M. Culnan, A. Bretscher, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Insight into the molecular basis of pathogen abundance: group A Streptococcus inhibitor of complement inhibits bacterial adherence and internalization into human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7646-7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kajava, A. V., and B. Kobe. 2002. Assessment of the ability to model proteins with leucine-rich repeats in light of the latest structural information. Protein Sci. 11:1082-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapur, V., J. T. Maffei, R. S. Greer, L. L. Li, G. J. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 1994. Vaccination with streptococcal extracellular cysteine protease (interleukin-1 beta convertase) protects mice against challenge with heterologous group A streptococci. Microb. Pathog. 16:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kehoe, M. A., V. Kapur, A. M. Whatmore, and J. M. Musser. 1996. Horizontal gene transfer among group A streptococci: implications for pathogenesis and epidemiology. Trends Microbiol. 4:436-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobe, B., and J. Deisenhofer. 1993. Crystal structure of porcine ribonuclease inhibitor, a protein with leucine-rich repeats. Nature 366:751-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobe, B., and J. Deisenhofer. 1994. The leucine-rich repeat: a versatile binding motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:415-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobe, B., and A. V. Kajava. 2001. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.LaPenta, D., C. Rubens, E. Chi, and P. P. Cleary. 1994. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12115-12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lecuit, M., H. Ohayon, L. Braun, J. Mengaud, and P. Cossart. 1997. Internalin of Listeria monocytogenes with an intact leucine-rich repeat region is sufficient to promote internalization. Infect. Immun. 65:5309-5319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lecuit, M., S. Vandormael-Pournin, J. Lefort, M. Huerre, P. Gounon, C. Dupuy, C. Babinet, and P. Cossart. 2001. A transgenic model for listeriosis: role of internalin in crossing the intestinal barrier. Science 292:1722-1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee, J. O., P. Rieu, M. A. Arnaout, and R. Liddington. 1995. Crystal structure of the A domain from the alpha subunit of integrin CR3 (CD11b/CD18). Cell 80:631-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leung, K. Y., B. S. Reisner, and S. C. Straley. 1990. YopM inhibits platelet aggregation and is necessary for virulence of Yersinia pestis in mice. Infect. Immun. 58:3262-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leung, K. Y., and S. C. Straley. 1989. The yopM gene of Yersinia pestis encodes a released protein having homology with the human platelet surface protein GPIb alpha. J. Bacteriol. 171:4623-4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lima, C. D., M. G. Klein, and W. A. Hendrickson. 1997. Structure-based analysis of catalysis and substrate definition in the HIT protein family. Science 278:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lukomski, S., N. P. Hoe, I. Abdi, J. Rurangirwa, P. Kordari, M. Liu, S. J. Dou, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Nonpolar inactivation of the hypervariable streptococcal inhibitor of complement gene (sic) in serotype M1 Streptococcus pyogenes significantly decreases mouse mucosal colonization. Infect. Immun. 68:535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lukomski, S., K. Nakashima, I. Abdi, V. J. Cipriano, R. M. Ireland, S. D. Reid, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and characterization of the scl gene encoding a group A Streptococcus extracellular protein virulence factor with similarity to human collagen. Infect. Immun. 68:6542-6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marino, M., L. Braun, P. Cossart, and P. Ghosh. 2000. A framework for interpreting the leucine-rich repeats of the Listeria internalins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8784-8788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marino, M., L. Braun, P. Cossart, and P. Ghosh. 1999. Structure of the lnlB leucine-rich repeats, a domain that triggers host cell invasion by the bacterial pathogen L. monocytogenes. Mol. Cell 4:1063-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McDonald, C., P. O. Vacratsis, J. B. Bliska, and J. E. Dixon. 2003. The Yersinia virulence factor YopM forms a novel protein complex with two cellular kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278:18514-18523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McIver, K. S., and J. R. Scott. 1997. Role of mga in growth phase regulation of virulence genes of the group A Streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 179:5178-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Medina, E., O. Goldmann, A. W. Toppel, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2003. Survival of Streptococcus pyogenes within host phagocytic cells: a pathogenic mechanism for persistence and systemic invasion. J. Infect. Dis. 187:597-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mengaud, J., H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, R. M. Mege, and P. Cossart. 1996. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenes into epithelial cells. Cell 84:923-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miao, E. A., C. A. Scherer, R. M. Tsolis, R. A. Kingsley, L. G. Adams, A. J. Baumler, and S. I. Miller. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium leucine-rich repeat proteins are targeted to the SPI1 and SPI2 type III secretion systems. Mol. Microbiol. 34:850-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Molinari, G., S. R. Talay, P. Valentin-Weigand, M. Rohde, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1997. The fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, SfbI, is involved in the internalization of group A streptococci by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:1357-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Musser, J. M., A. R. Hauser, M. H. Kim, P. M. Schlievert, K. Nelson, and R. K. Selander. 1991. Streptococcus pyogenes causing toxic-shock-like syndrome and other invasive diseases: clonal diversity and pyrogenic exotoxin expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2668-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Musser, J. M., and R. M. Krause. 1998. The revival of group A streptococcal diseases, with a commentary on staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, p. 185-218. In R. M. Krause (ed.), Emerging infections. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 63.O'Connor, S. P., and P. P. Cleary. 1987. In vivo Streptococcus pyogenes C5a peptidase activity: analysis using transposon- and nitrosoguanidine-induced mutants. J. Infect. Dis. 156:495-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Omburo, G. A., T. J. Torphy, G. Scott, S. Jacobitz, R. F. Colman, and R. W. Colman. 1997. Inactivation of recombinant monocyte cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase by cAMP analog, 8-[(4-bromo-2,3-dioxobutyl)thio]adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Blood 89:1019-1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Podbielski, A., B. Spellerberg, M. Woischnik, B. Pohl, and R. Lutticken. 1996. Novel series of plasmid vectors for gene inactivation and expression analysis in group A streptococci (GAS). Gene 177:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. A. Leonard, and K. H. Schmidt. 1999. Characterization of nra, a global negative regulator gene in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1051-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raffelsbauer, D., A. Bubert, F. Engelbrecht, J. Scheinpflug, A. Simm, J. Hess, S. H. Kaufmann, and W. Goebel. 1998. The gene cluster inlC2DE of Listeria monocytogenes contains additional new internalin genes and is important for virulence in mice. Mol. Gen. Genet. 260:144-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, J. K. Buss, B. Lei, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Multilocus analysis of extracellular putative virulence proteins made by group A Streptococcus: population genetics, human serologic response, and gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7552-7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reid, S. D., N. M. Green, G. L. Sylva, J. M. Voyich, E. T. Stenseth, F. R. DeLeo, T. M. Palzkill, D. E. Low, H. R. Hill, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Postgenomic analysis of four novel antigens of group A Streptococcus: growth-phase-dependent gene transcription and human serologic response. J. Bacteriol. 184:6316-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reid, S. D., N. P. Hoe, L. M. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Group A Streptococcus: allelic variation, population genetics, and host-pathogen interactions. J. Clin. Investig. 107:393-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reid, S. D., K. Virtaneva, and J. M. Musser. Group A Streptococcus vaccine research: historical synopsis and new insights. In R. W. Ellis and B. R. Brodeur (ed.), New bacterial vaccines, in press. Landes Bioscience, Georgetown, Tex.

- 72.Schubert, W. D., G. Gobel, M. Diepholz, A. Darji, D. Kloer, T. Hain, T. Chakraborty, J. Wehland, E. Domann, and D. W. Heinz. 2001. Internalins from the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes combine three distinct folds into a contiguous internalin domain. J. Mol. Biol. 312:783-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schubert, W. D., C. Urbanke, T. Ziehm, V. Beier, M. P. Machner, E. Domann, J. Wehland, T. Chakraborty, and D. W. Heinz. 2002. Structure of internalin, a major invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes, in complex with its human receptor E-cadherin. Cell 111:825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smoot, J. C., K. D. Barbian, J. J. Van Gompel, L. M. Smoot, M. S. Chaussee, G. L. Sylva, D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Ricklefs, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, S. B. Beres, D. S. Campbell, T. M. Smith, Q. Zhang, V. Kapur, J. A. Daly, L. G. Veasy, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence and comparative microarray analysis of serotype M18 group A Streptococcus strains associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4668-4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sutcliffe, I. C., and D. J. Harrington. 2002. Pattern searches for the identification of putative lipoprotein genes in gram-positive bacterial genomes. Microbiology 148:2065-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sutcliffe, I. C., and R. R. Russell. 1995. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 177:1123-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsolis, R. M., S. M. Townsend, E. A. Miao, S. I. Miller, T. A. Ficht, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Baumler. 1999. Identification of a putative Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium host range factor with homology to IpaH and YopM by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 67:6385-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vallee, B. L., and D. S. Auld. 1990. Active-site zinc ligands and activated H2O of zinc enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:220-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vallee, B. L., and D. S. Auld. 1990. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry 29:5647-5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Voyich, J. M., D. E. Sturdevant, K. R. Braughton, S. D. Kobayashi, B. Lei, K. Virtaneva, D. W. Dorward, J. M. Musser, and F. R. DeLeo. 2003. Genome-wide protective response used by group A Streptococcus to evade destruction by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:1996-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wessels, M. R. 2000. Capsular polysaccharide of group A Streptococcus, p. 34-42. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 83.Zhang, Y., A. W. Masi, V. Barniak, K. Mountzouros, M. K. Hostetter, and B. A. Green. 2001. Recombinant PhpA protein, a unique histidine motif-containing protein from Streptococcus pneumoniae, protects mice against intranasal pneumococcal challenge. Infect. Immun. 69:3827-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]