Abstract

Calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D3) is cytostatic for prostate cancer (CaP) but had limited therapeutic utility due to hypercalcemia-related toxicities, leading to the development of low-calcemic calcitriol analogs. We show that one analog, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D5 (1α(OH)D5), induced apoptosis in castration-sensitive LNCaP prostate cancer cells but, unlike calcitriol, did not increase androgen receptor (AR) transcriptional activity. LNCaP-AI, a castrate-resistant (CRCaP) LNCaP subline, was resistant to 1α(OH)D5 in the presence of androgens; however, androgen withdrawal (AWD), although ineffective by itself, sensitized LNCaP-AI cells to 1α(OH)D5. Investigation of the mechanism revealed that the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which mediates the effects of 1α(OH)D5, is downregulated in LNCaP-AI cells compared to LNCaP in the presence of androgens, whereas AWD restored VDR expression. Since LNCaP-AI cells expressed higher AR compared to LNCaP and AWD decreased AR, this indicated an inverse relationship between VDR and AR. Further, AR stimulation (by increased androgen) suppressed VDR, while AR downregulation (by ARsiRNA) stimulated VDR levels and sensitized LNCaP-AI cells to 1α(OH)D5 similar to AWD. Another cell line, pRNS-1-1, although isolated from a normal prostate, had lost AR expression in culture and adapted to androgen-independent growth. These cells expressed the VDR and were sensitive to 1α(OH)D5, but restoration of AR expression suppressed VDR levels and induced resistance to 1α(OH)D5 treatment. Taken together, these results demonstrate negative regulation of VDR by AR in CRCaP cells. This effect is likely mediated by prohibitin (PHB), which was inhibited by AR transcriptional activity and stimulated VDR in CRCaP but not castrate-sensitive cells. Therefore, in castration-sensitive cells, although the AR negatively regulates PHB, this does not affect VDR expression, whereas in CRCaP cells, negative regulation of PHB by the AR results in concomitant negative regulation of the VDR by the AR. These data demonstrate a novel mechanism by which 1α(OH)D5 prolongs the effectiveness of AWD in CaP cells.

Keywords: calcitriol, vitamin D5, androgen receptor, vitamin D receptor, prostate cancer

Introduction

Since the growth of prostate cancer (CaP) is initially dependent on androgens, first-line treatment for recurrent CaP is androgen withdrawal therapy (AWD), to which 95% of tumors initially respond.1 First-line hormonal therapy usually consists of LHRH agonists, which prevent the production of testicular androgens. However, patients on this treatment relapse within 18 to 24 months, at which time they are placed on complete androgen blockade (CAB) involving the use of androgen receptor (AR) antagonists such as bicalutamide (Casodex, AstraZeneca, London, United Kingdom), a competitive inhibitor of AR ligand binding, together with AWD.2 Although the majority of these patients continue to express the AR, which transcriptionally regulates the expression of multiple genes, including prostate-specific antigen (PSA),3 only about 25% to 30% of patients respond to this second-line hormonal therapy, indicating the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRCaP). Therapeutic options for patients who develop CRCaP are limited: clinical trials reveal that United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs for CRCaP patients, including the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel,4,5 and the cancer “vaccine” sipuleucel-T (Provenge, Dendreon Corporation, Seattle, WA),6 increased survival by only 3 and 4 months, respectively. Hence, the long-term goal of this project is to identify therapeutic targets that would prevent CaP progression to CRCaP.

The naturally occurring active metabolite of vitamin D, 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 (1α,25(OH)2D3, calcitriol), inhibits CaP growth and induces apoptosis in CaP cells.7-9 However, the utility of calcitriol has been severely limited because its antitumor activity is achieved at doses that cause toxicity due to hypercalcemia,10-12 which at high serum calcium levels (≥12.0 mg/dL or 3 mmol/L), leading to increased intestinal and renal calcium absorption, may cause intestinal and renal toxicity, whereas severe hypercalcemia has been known to induce coma and cardiac arrest. Phase III studies in patients with CRCaP utilizing high-dose calcitriol in combination with docetaxel were terminated due to overall decreased survival in comparison with docetaxel alone.13

Development of synthetic analogs of the vitamin D molecule that preserve its antiproliferative and cell-differentiating properties while minimizing or eliminating its toxic profile has been ongoing. Calcitrol-induced hypercalcemia is related to the presence of the OH group at C-25 of this compound. To reduce toxicity, a compound of the vitamin D5 family, rather than the D3 family, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D5 (1α(OH)D5), has been constructed and was shown to lack hydroxylation at the C-25 position and to contain an ethyl group at C-24.14 1α(OH)D5 (1 µM), similar to calcitriol (100 nM), inhibited the development of DMBA-induced preneoplastic lesions in mouse mammary glands14 or N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU)–induced mammary carcinogenesis in female rats.15 However, unlike calcitriol, 1α(OH)D5 did not increase plasma calcium levels at any dose tested in male rats and did not affect body weight.14-16 These results indicate the low-calcemic nature of 1α(OH)D5 and lower toxicity, in comparison with calcitriol, despite its tumor-suppressive properties. However, this drug has never been used in prostate cancer cells. The objective of the studies described here is to demonstrate that despite decreased cytotoxicity, 1α(OH)D5 is still as effective as the parent compound, calcitriol, in preventing prostate cancer cell growth.

Studies showed that AWD does not induce cell death but rather results in cell cycle arrest, whereas CRCaP development triggers a release from that arrest, and cell cycle progression, even in the absence of androgens.17 Thus, the induction of apoptosis during AWD would prevent CRCaP by depleting the system of cells that have the capability to progress. Here, we show that 1α(OH)D5 induced apoptosis in CRCaP cells during AWD, indicating that it would be suitable as adjuvant therapy to improve the effects of AWD. Further, androgens activate the AR, which is required for the growth and survival of not only castrate-sensitive but also CRCaP cells.18-20 About 30% of CRCaP tumors express higher AR compared to the corresponding androgen-dependent primary tumor.3 Thus, an increase in AR transcriptional activity would ultimately promote CRCaP cell growth. Calcitriol was shown to induce AR transcriptional activity, especially in LNCaP prostate cancer cells,21 and this could possibly be a mechanism of resistance to calcitriol in these cells. However, we now show that unlike calcitriol, 1α(OH)D5 did not induce AR transcriptional activity. This indicates an additional benefit of 1α(OH)D5 over calcitriol in the treatment of CaP cells.

The genomic effects of vitamin D are mediated by the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which, like the AR, is a steroid nuclear receptor.21 Multiple studies reported that calcitriol is more effective in castration-sensitive CaP cell lines such as LNCaP and to some extent in AR-null cell lines such as PC-3, compared to AR-positive CRCaP sublines of LNCaP.9,21,22 In this study, we observe a similar effect with 1α(OH)D5 and investigate the mechanism. Previous studies indicated negative regulation of VDR transcriptional activity by the AR23; however, we now show that the AR is a negative regulator of VDR expression in CRCaP cells but not castrate-sensitive cells. Our results demonstrate that in LNCaP cells, VDR is strongly expressed in the presence of androgens, and 1α(OH)D5, similar to calcitriol, is effective in suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis in these cells. However, LNCaP-AI cells, developed by prolonged culture of LNCaP cells in the absence of androgens, express very high levels of AR, which suppressed VDR levels and desensitized the cells to 1α(OH)D5, whereas AWD resensitized CRCaP cells to 1α(OH)D5 by inhibiting the AR and stimulating the VDR.

We also show that the interaction between the AR and the VDR in CRCaP cells is likely mediated by a novel mechanism involving the cell cycle regulator prohibitin (PHB), which was previously shown to interact with the AR in CaP cells. PHB is a highly conserved 32-kDa protein that localizes both in the mitochondria and the nucleus and appears to play different roles at the 2 locations.24 In the mitochondria, it is a mitochondrial chaperone protein that complexes with BaP37/REA, whereas in the nucleus, it acts as a cell cycle regulator that antagonizes E2F1-mediated gene activation by recruitment of transcriptional repressors including the nuclear corepressor (NCoR), retinoblastoma protein (Rb), and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1).25,26 PHB has been called a tumor suppressor due to its ability to block DNA synthesis and induce apoptosis.24,27 In prostate tumor cells, PHB was shown to be negatively regulated by androgens28 and is also a negative regulator of AR transcriptional activity.29 Suppression of AR activity by AR antagonists required PHB, in complex with the SWI/SNF core protein BRG1.30 Reduction of PHB promoted both androgen-dependent and -independent tumor growth in vivo.31 Significantly, the growth-inhibitory ability of vitamin D5 in breast cancer cells was also traced to PHB.32,33

In this study, we show that in androgen-dependent cells, VDR expression is not regulated by PHB, and the AR does not have an inhibitory effect on VDR. However, CRCaP cells likely undergo a phenotypic change, such that VDR expression is now regulated by PHB; hence, the AR, which is a negative regulator of PHB, also can negatively regulate the VDR. As a result, 1α(OH)D5, in combination with AWD, inhibits growth of CRCaP cells. Taken together, these results show that 1α(OH)D5 prolongs the effectiveness of AWD in CaP cells.

Results

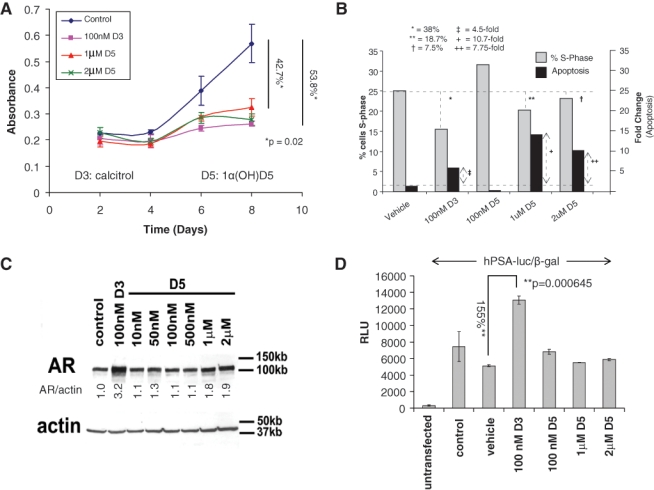

1α(OH)D5 inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in castration-sensitive LNCaP prostate cancer cells

We first investigated whether 1α(OH)D5 was effective in inhibiting the growth of CaP cells. To compare the effects of 1α(OH)D5 with calcitriol in castration-sensitive cells, LNCaP cells were treated in “complete” medium (with fetal bovine serum [FBS] containing androgens) with vehicle (ethanol, control), 100 nM calcitriol, and increasing doses of 1α(OH)D5. At concentrations <1 µM, 1α(OH)D5 had no significant effect on proliferation (not shown), while 1 to 2 µM 1α(OH)D5 had an equivalent cytostatic effect (42.72% decrease with 1 µM, P = 0.017, and 51.18% decrease with 2 µM, P = 0.015) as 100 nM calcitriol (53.8% decrease, P = 0.018) (Fig. 1A). By flow cytometry, calcitriol (100 nM) was shown to inhibit proliferation (38% decrease in S-phase compared to vehicle-treated cells) and induce apoptosis (4.48-fold increase in apoptosis v. vehicle-treated cells) (Fig. 1B). Compared to calcitriol, 1α(OH)D5 had a smaller effect on cell cycle arrest, but the effect on apoptosis was greater (10.7-fold and 7.5-fold increase in apoptosis compared to vehicle-treated cells, respectively) (Fig. 1B). LNCaP cells were growth arrested (75.36% inhibition after 5 days, P < 0.0001) upon culture in medium containing charcoal stripped FBS (CSS), which, among other factors, contain decreased levels of androgens, and neither calcitriol nor 1α(OH)D5 enhanced this effect (calcitriol + CSS, 71.6% inhibition, P = 0.0004; 1α(OH)D5 + CSS, 75.81% inhibition, P < 0.0001; data not shown).

Figure 1.

1α(OH)D5 inhibits cell growth and survival but does not induce AR levels or transcriptional activity in androgen-dependent LNCaP prostate cancer cells. LNCaP cells cultured in medium with androgens (FBS) and exposed to either calcitriol (D3) or 1α(OH)D5 (D5). (A) Cell number increase was estimated by MTT assay and indicated comparable cytostatic effects of 100 nM D3 and 1 to 2 µM D5. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent readings. (B) Flow cytometric analysis to compare effects of calcitriol versus 1α(OH)D5 on cell proliferation and apoptosis. LNCaP cells were treated with vehicle or calcitriol or different concentrations of 1α(OH)D5 for 48 hours. Change in S-phase is recorded as percentage change over vehicle-treated cells and change in apoptosis as fold change over vehicle-treated cells. (C) AR levels assessed by immunoblotting in LNCaP cells showing AR induction by D3 but not by D5. β-actin was assessed as loading control. Numbers under each lane represent fold change in band intensity normalized to that of the control band. These experiments were repeated at least 3 times with similar results. (D) LNCaP cells left untransfected or transfected with hPSA-luc and β-gal were treated as shown for 72 hours. AR transcriptional activity was determined by luciferase assay and shows increased activity in D3- but not D5-treated cells. Data of hPSA-gal/β-gal shown as mean ± SD of 3 independent readings.

It is well known that calcitriol upregulates levels of the AR and its transcriptional target, PSA, in LNCaP cells in vitro.9,34,35 Hence, we investigated the same for 1α(OH)D5. Immunoblotting confirmed that in LNCaP cells, calcitriol substantially increased the expression of the AR (3.2-fold) starting 4 days after treatment (not shown) and had a pronounced effect by 8 days (Fig. 1C). However, 1α(OH)D5 at cytostatically equivalent concentrations (1 and 2 µM) showed minimal effect (less than 2-fold increase in AR expression) (Fig. 1C). AR transcriptional activity as determined by luciferase assay on a plasmid encoding for the human PSA promoter tagged to a luciferase construct (hPSA-luc) was increased 155% (2.5-fold) by treatment with 100 nM calcitriol but showed no change with 1α(OH)D5 (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results indicate that 1α(OH)D5, like calcitriol, had a cytostatic effect on androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells, although by a mechanism different from calcitriol, but, unlike the latter, did not enhance AR transcriptional activity in LNCaP cells.

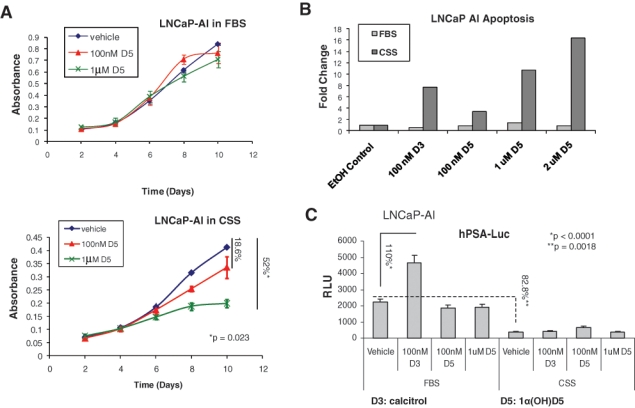

LNCaP-AI, a CRCaP subline of LNCaP cells, is sensitive to growth inhibition by 1α(OH)D5 in the absence, not presence, of AR transcriptional activity

We next determined whether 1α(OH)D5 was also useful in CRCaP cells. Previous studies had shown that calcitriol was less effective in castrate-resistant sublines of LNCaP cells21; hence, we tested the effects of 1α(OH)D5 on one such line, LNCaP-AI, which we had developed by continuous culture of LNCaP cells in CSS medium for prolonged periods of time, as described elsewhere.36,37 Unlike LNCaP, LNCaP-AI cells were not significantly growth arrested by treatment with 1α(OH)D5 in the presence of FBS (15% inhibition with 1 µM, P = 0.27) (Fig. 2A, upper panel). However, in medium containing CSS, which have lower levels of androgens and other hormones, LNCaP-AI cells were significantly growth inhibited by 1 µM 1α(OH)D5 (51.94% inhibition, P = 0.023), although vehicle-treated LNCaP-AI cells continued to proliferate (Fig. 2A, lower panel). Flow cytometric analysis indicated that in the presence of FBS, both calcitriol and 1α(OH)D5 failed to induce apoptosis in LNCaP-AI cells, whereas in CSS, substantial apoptosis was observed with both drugs (Fig. 2B). A similar effect was also seen using C4-2 cells, a commercially available CRCaP subline of LNCaP cells obtained from tumors developed in castrated nude mice,38 which has been extensively described by us previously39-41 (Suppl. Fig. S1). Thus, our results indicate that CRCaP sublines of LNCaP cells were growth inhibited by 1α(OH)D5 in CSS medium despite neither 1α(OH)D5 nor culture in CSS being individually growth inhibitory in these cells.

Figure 2.

1α(OH)D5 inhibits growth of LNCaP-AI cells, a castration-resistant subline of LNCaP, in charcoal stripped serum (CSS) but not in complete medium containing FBS. LNCaP-AI cells were cultured in (A) complete medium containing FBS (upper panel) or phenol red–free medium containing CSS (lower panel) for the periods indicated in the presence of vehicle (ethanol) or 100 nM versus 1 µM 1α(OH)D5 (D5). Growth rates estimated by MTT assay indicate greater effect of D5 in CSS compared to FBS. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). (B) Flow cytometry to determine the effect of D3 and increasing doses of D5 on LNCaP-AI cell apoptosis. Cells were cultured in medium containing FBS or CSS for 5 days, and the cells were trypsinized and stained with propidium iodide and annexin V prior to flow cytometry. Data represent fold change over number of cells undergoing apoptosis in cells treated with ethanol (EtOH control). (C) AR transcriptional activity with calcitriol versus 1α(OH)D5 in FBS versus CSS as determined by luciferase assay in hPSA-luc and β-gal transfected cells. Note the increased AR activity in the presence of D3, which was not apparent in the presence of D5. Data represent mean ± SD of 3 independent readings.

Like LNCaP cells, LNCaP-AI experienced no increase in AR activity on a PSA promoter with 1α(OH)D5 as determined by luciferase assay, although calcitriol still increased PSA transcription in FBS medium (110% [2.1-fold] increase, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2C). However, even calcitriol failed to induce AR activity in CSS medium, indicating that the effect was ligand dependent. These results indicate the effectiveness of 1α(OH)D5 in the inhibition of cell growth in CRCaP cells in combination with AWD.

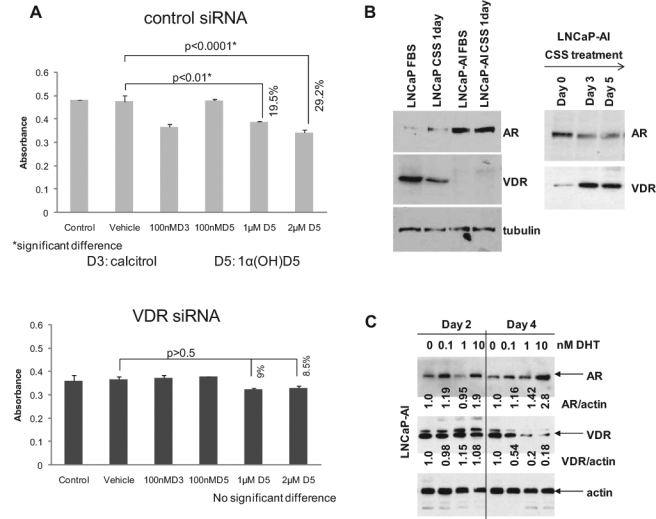

The effects of 1α(OH)D5 are mediated by the VDR, which is suppressed in LNCaP-AI cells by high androgen and AR levels

We next investigated whether there is a link between AR transcriptional activity and the growth inhibitory effect of 1α(OH)D5 in CaP cells. The genomic effects of calcitriol are regulated by the VDR; hence, we determined whether the effects of 1α(OH)D5 were mediated by the VDR as well. LNCaP-AI cells subjected to control siRNA for 48 hours showed approximately 29% reduced growth rates when treated with 2 µM 1α(OH)D5 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A, upper), but cells that were depleted of VDR with VDR siRNA for the same time period failed to respond to 1α(OH)D5 (Fig. 3A, lower). The extent of VDR downregulation by VDR siRNA is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. These results indicate that the effects of 1α(OH)D5 on cell growth are mediated by the VDR. Next, we compared the levels of AR and VDR in the 2 cell lines studied. LNCaP-AI cells expressed higher AR and lower VDR levels compared to LNCaP (Fig. 3B, left). Together, these data explain the differential effects of 1α(OH)D5 in LNCaP versus LNCaP-AI cells; in medium with FBS, LNCaP cells responded to 1α(OH)D5 because it expressed high levels of VDR, whereas LNCaP-AI cells did not respond due to lower VDR expression.

Figure 3.

The androgen receptor (AR) negatively regulates the levels of the vitamin D receptor (VDR). (A) 1α(OH)D5-induced growth inhibition is mediated by the VDR. (Upper) LNCaP-AI cells cultured in CSS medium treated with control siRNA were growth inhibited by 48-hour treatment with 1 to 2 µM 1α(OH)D5, as determined by MTT assay (note that the higher inhibition rates observed in previous figures were achieved after longer periods of treatment), but (lower) the same cell line subjected to VDR siRNA for the same time period showed no statistically significant response to 1α(OH)D5. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3). (B) Negative correlation between the AR and the VDR. (Left) LNCaP-AI cells express higher levels of AR and lower levels of VDR compared to LNCaP, (right) but when LNCaP-AI cells were cultured for >24 hours in CSS, AR levels declined while VDR levels increased. (C) Prolonged treatment with DHT inhibited VDR levels. LNCaP-AI cells were treated with increasing doses of DHT. AR expression increased with increasing concentration of DHT (upper panel). In contrast, VDR levels decreased after 4 days but not 2 days of treatment (middle panel). Numbers under each lane represent fold change in band intensity normalized to that of control.

Our data indicated that culture in CSS for 24 hours slightly decreased VDR expression (Fig. 3B, left). This observation is in support of previous reports demonstrating positive correlation between AR and VDR expression in LNCaP cells.23 However, prolonged culture in CSS increased VDR expression in LNCaP-AI cells (Fig. 3B, right), coinciding with a renewed response of these cells to 1α(OH)D5 in CSS medium. Hence, we investigated the cause for CSS-induced increase in VDR expression. Charcoal stripping removes available androgens in FBS, together with other steroids and growth factors; hence, we investigated whether the effects of CSS observed above relate to the removal of androgens from the medium. Prolonged (4-day, but not 2-day) treatment with increasing doses of the androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT) increased AR and decreased VDR expression (Fig. 3C), indicating that the AR has a suppressive effect on VDR expression in prostate cancer cells.

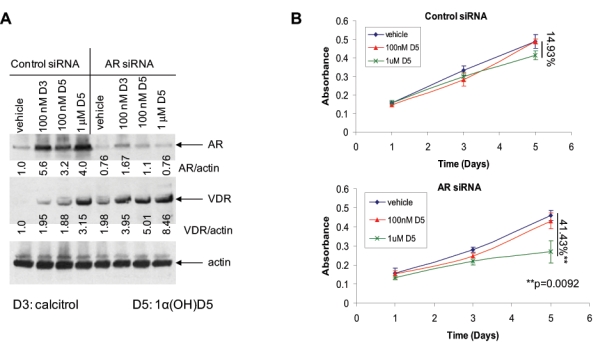

AR downregulation increased VDR expression in LNCaP-AI cells and sensitized them to 1α(OH)D5

Since LNCaP-AI cells expressed higher AR and lower VDR levels compared to LNCaP, we investigated whether increased AR seen in LNCaP-AI cells suppressed VDR function, thereby desensitizing these cells to 1α(OH)D5. In cells subjected to control siRNA only, treatment with calcitriol, and to some extent, 1α(OH)D5, induced AR expression; however, AR siRNA significantly inhibited AR levels (Fig. 4A, upper panel). VDR expression was induced by both calcitriol and 1α(OH)D5 in cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 4A, middle panel). However, inhibition of AR expression by AR siRNA enhanced VDR expression in vehicle-treated, calcitriol, and 1α(OH)D5-treated cells (Fig. 4A, middle panel). This supported our previous observation that the AR antagonized VDR expression in LNCaP-AI cells.

Figure 4.

Downregulation of the AR by AR siRNA sensitizes LNCaP-AI cells to 1α(OH)D5. (A) An AR siRNA, which downregulated AR expression, but not a pool of control (nonspecific) siRNA duplexes, stimulated VDR levels. The AR siRNA, but not a control siRNA, downregulated AR expression, especially that induced by vitamin D3 and D5 treatment (upper panel), and induced VDR expression (middle panel). Results were normalized to levels of actin, which acted as loading control (lower panel). Numbers under each band represent fold change in band intensity normalized to actin with respect to that of the vehicle-treated control cells. (B) LNCaP-AI cells were transfected with control siRNA or AR-specific siRNA in the presence of D5, and changes in cell numbers in the presence of control or AR siRNA were estimated by MTT assay (upper). In the presence of the control siRNA, the effect of D5 on the growth of these cells was not significant, (lower) but AR downregulation with AR siRNA sensitized these cells to D5, which induced a 41.43% decrease in cell growth rates (P = 0.0092) versus 14.93% decrease (P > 0.5) with control siRNA (mean ± standard deviation [SD], n = 3).

The above results predicted that decreased AR expression sensitizes LNCaP-AI cells to the effects of 1α(OH)D5. Hence, we subjected LNCaP-AI cells to control and AR siRNA and determined the growth-inhibitory effects of 1α(OH)D5 under these conditions. As before, LNCaP-AI cells grown in FBS and subjected to control siRNA were resistant to growth inhibition by 1 µM 1α(OH)D5 (14.93% inhibition only, P > 0.05) (Fig. 4B, upper). However, downregulation of AR expression with AR siRNA sensitized these cells to 1α(OH)D5 even in the presence of FBS (41.43% inhibition, P = 0.0092) (Fig. 4B, lower). Taken together, these results indicate that the activation of the AR suppresses VDR levels and also the response of LNCaP-AI cells to 1α(OH)D5, whereas AR inhibition relieves this suppression and sensitizes these cells to the drug.

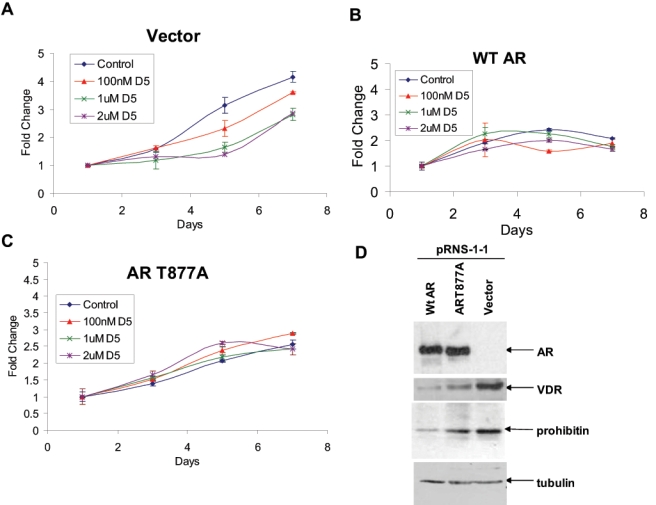

AR overexpression antagonizes the vitamin D receptor, suppresses the expression of prohibitin, and prevents responsiveness to 1α(OH)D5 in pRNS-1-1 cells

Next, we investigated whether an increase in AR expression can suppress VDR expression. For this purpose, we used pRNS-1-1 cells derived from prostate epithelial cells, which had subsequently lost AR expression and adapted to androgen-independent growth (described by us36,42). To determine the effect of AR overexpression on the effect of 1α(OH)D5, pRNS-1-1 cells were stably transfected with vector alone, or wild-type AR (wtAR), and subjected to increasing doses of 1α(OH)D5. However, since the previous figures showed experiments that were all conducted in LNCaP cells and its CRCaP sublines, which endogenously express a mutant AR (T877A), we also used cells stably transfected with the AR mutant to determine whether they behaved similarly to those expressing wtAR. The cells stably transfected with vector alone responded to increasing doses of 1α(OH)D5 (1 µM: 57% decrease after 5 days, P = 0.0022; 2 µM: 71.7% decrease, P = 0.0131) (Fig. 5A); however, when transfected with wild-type AR (1 µM: 11.2% decrease after 5 days, P > 0.05; 2 µM: 15.6% decrease, P = 0.0013) (Fig. 5B) or AR T877A (1 µM: 15.9% decrease after 5 days, P = 0.0254; 2 µM: 6.01% decrease, P = 0.0119) (Fig. 5C), these cells lost the ability to respond to 1α(OH)D5. Investigation into the cause of this loss of response revealed that pRNS-1-1 cells stably expressing wild-type AR or AR(T877A) expressed significantly less VDR compared to those expressing vector alone (Fig. 5D, upper panels). Thus, the expression of the AR prevents sensitivity to 1α(OH)D5 in pRNS-1-1 cells by repressing VDR expression. These results confirm our previous observations that the AR is a suppressor of VDR expression.

Figure 5.

Expression of AR in AR-null pRNS-1-1 cells derived from a normal prostate desensitized these cells to 1α(OH)D5. (A) pRNS-1-1 cells stably transfected with vector only responded to 1α(OH)D5. (B) pRNS-1-1 cells stably transfected with wild-type AR (wtAR) demonstrated decreased response to 1α(OH)D5. (C) pRNS-1-1 cells stably transfected with a mutant AR (T877A) responded even less to 1α(OH)D5. (D) Expression of wild-type or mutant AR in pRNS-1-1 cells inhibited VDR and prohibitin expression. (Upper panel) Parental pRNS-1-1 cells were transfected with vector only or wild-type or mutant AR. (Second panel) Overexpression of AR in pRNS-1-1 cells, but not the vector, suppressed the expression of VDR, (third panel) as well as that of prohibitin. (Bottom panel) Loading control as detected by the expression of α-tubulin.

Next, we investigated the mechanism by which the AR regulates VDR expression in prostate cancer cells. Previous reports indicated that androgens downregulate the expression of prohibitin (PHB),28 while 1α(OH)D5 stimulated PHB in breast cancer cells32; these reports suggested that PHB may interact with both the AR and VDR. Based on these reports, we investigated the levels of PHB in the various pRNS-1-1 mutant cell lines used. In support of a positive correlation between the VDR and PHB, and a negative effect on both by the AR, expression of wild-type or mutant AR in pRNS-1-1 cells suppressed PHB expression (Fig. 5D, third panel). Taken together, these results indicate a common relationship between the AR, VDR, and PHB.

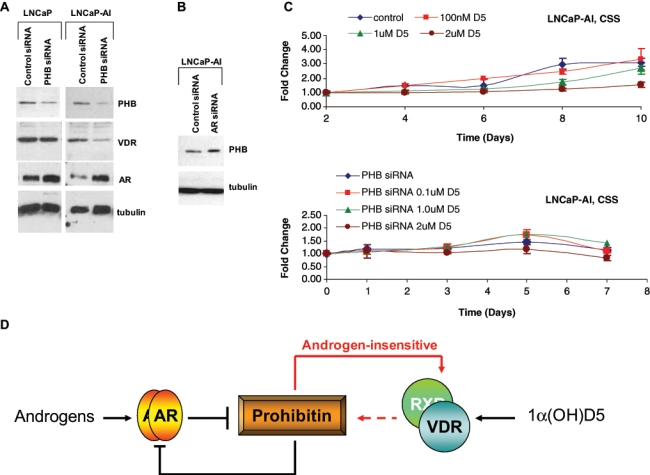

AR-induced suppression of VDR expression and sensitivity to 1α(OH)D5 are mediated by its effect on prohibitin

Since our previous results indicate a common effect of AR expression on VDR and PHB levels in pRNS-1-1 cells, we investigated whether PHB mediated the interaction between the VDR and the AR. Downregulation of PHB expression with a pool of 3 PHB-specific siRNA duplexes in LNCaP and LNCaP-AI cells not only resulted in an upregulation of AR levels (Fig. 6A, third panel), as previously reported by others,29,30 but also in downregulation of VDR expression in LNCaP-AI but not in LNCaP cells (Fig. 6A, second panel). On the other hand, downregulation of AR expression in LNCaP-AI cells increased PHB expression (Fig. 6B) in accordance with reports in the literature.28 Together with a lack of AR regulation of the VDR in LNCaP cells, but strong AR regulation of VDR in LNCaP-AI cells, these results indicate that expression or activation of the AR in CaP cells suppresses PHB expression and that in CRCaP cells, but not in castration-sensitive cells, this in turn prevents the expression of the VDR.

Figure 6.

Prohibitin (PHB) mediates the effects of 1α(OH)D5 in androgen-insensitive, but not androgen-sensitive, prostate cancer cells. (A) LNCaP (left) and LNCaP-AI cells (right) were subjected to control (nonspecific) siRNA or PHB siRNA and the effect of these treatments on PHB levels (upper panel), VDR levels (second panel), AR levels (third panel), and tubulin (fourth panel) determined by Western blotting. Note that PHB downregulation stimulated AR levels in both LNCaP and LNCaP-AI, as reported by others,29 but affected VDR expression only in LNCaP-AI. (B) Downregulation of AR expression in LNCaP-AI cells increases PHB levels. LNCaP-AI cells were subjected to control or AR siRNA, and PHB levels were determined by Western blotting. Tubulin levels were determined as loading control. (C) The growth-inhibitory effect of 1α(OH)D5 in LNCaP-AI cells in CSS medium requires an active PHB. Androgen-independent LNCaP-AI cells treated with control siRNA cultured in CSS medium respond to 1α(OH)D5 as determined by MTT assay (upper), whereas those treated with PHB siRNA duplexes do not (lower). (D) Scheme depicting PHB mediation of the effects of AR on VDR in androgen-insensitive cells. Red lines depict effects seen only in androgen-independent prostate cancer.

The above indicate that PHB may mediate the interaction between the VDR and the AR; hence, we investigated whether PHB is required for the suppressive effect of the AR on VDR expression. Androgen-independent LNCaP-AI cells, which express a mutant AR(T877A), when cultured in CSS-containing medium, respond to 1α(OH)D5 in the presence of control siRNA (54% inhibition with 2 µM 1α(OH)D5, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6C, upper panel). However, upon PHB downregulation using the same siRNA duplex pool described in Figure 6A, these cells became less responsive to 1α(OH)D5 (28% inhibition at the same dose, P = 0.006) (Fig. 6C, lower panel). However, a similar response was not seen in LNCaP cells (not shown). These results indicate that PHB mediates androgen-regulated responsiveness of LNCaP-AI, but not LNCaP cells, to 1α(OH)D5.

Discussion

The overall objective of the studies described here is to determine whether 1α(OH)D5 in combination with AWD prevents CRCaP cell growth. The parent compound, calcitriol, has repeatedly demonstrated antiproliferative properties against CaP; however, the antineoplastic activity of calcitriol is achieved at doses that result in hypercalcemia and toxicity. Intermittent dose-intense calcitriol (DN-101), together with the chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel, was relatively successful in a phase II trial (AIPC Study of Calcitriol Enhancement of Taxotere [ASCENT]) but, despite early promise,43 did not achieve its primary endpoint for PSA response44; however, a much larger phase III international trial, ASCENT-2, was halted early due to decreased survival in the ASCENT arm compared to docetaxel alone.13 As investigators debate the revival of the ASCENT-2 trial, a number of low-calcemic analogs of the parental compound have been placed in clinical development; this includes 1α(OH)D5, which was used in the present studies.

Here, we show that treatment with 1 to 2 µM 1α(OH)D5 and 0.1 µM calcitriol inhibited growth in LNCaP cells to a similar extent. However, the mechanism by which these 2 drugs inhibit cell growth is different; whereas 1α(OH)D5 induced higher levels of apoptosis, calcitriol caused greater cell cycle arrest. It is likely that the difference in response of CaP cells to calcitriol and 1α(OH)D5 is attributable to the difference in binding affinities of these 2 reagents to the VDR since calcitriol has a higher binding affinity to the VDR compared to 1α(OH)D5 (Dr. Rajendra Mehta, unpublished observations). While nongenomic effects of calcitriol are well known,45 it remains to be seen whether 1α(OH)D5 also has nongenomic effects and whether they affect its induction of apoptosis.

The difference in proliferation versus apoptosis in calcitriol versus 1α(OH)D5 has significant implications regarding their use to prevent the growth of CaP cells. It was previously shown that in castration-sensitive LNCaP cells (but not in CRCaP cells), calcitriol was highly effective in the presence of FBS, whereas it was less effective in LNCaP cells cultured in media containing CSS, where androgen levels were lower.9,21,22 We hypothesize that if calcitriol at 100 nM mainly induces growth arrest, then it will be effective only against a cycling cell but would not have further effect upon culture in CSS, which is well known to cause LNCaP cells to undergo G1 arrest. Therefore, in castration-sensitive LNCaP cells, the effect of the VDR ligands in FBS versus CSS may be independent of AR regulation of VDR, whereas in castration-resistant cells, the effect is dependent on AR regulation of VDR expression. Since 1α(OH)D5 has a greater effect on LNCaP cells, we hypothesize that its effect in the long term may be greater. The current data could not be used to test this hypothesis because of the lack of sufficient LNCaP cells cultured in CSS-containing media available for flow cytometry in repeated experiments. Although other techniques to test this hypothesis are beyond the scope of this study, they are presently in progress in our laboratory.

It may be noted that while 1α(OH)D5 has a cytostatic effect at 10x the dose used for calcitriol, it is still effective since 100 nM calcitriol has been shown to be cytotoxic, whereas 1 µM 1α(OH)D5 was shown to be nontoxic.14,15,46 In addition, for a nontoxic drug, 1 µM is not an unrealistic dose; for example, the commonly used antiandrogen Casodex (AstraZeneca), which has a low toxicity profile, is used at a 50-mg daily dose to achieve an intraprostatic dose of approximately 10 µM. Although both calcitriol and 1α(OH)D5 were more effective in LNCaP cells cultured in the presence of androgens compared to its absence, in CRCaP sublines of LNCaP developed in our laboratory by continuous culture in CSS-containing medium (LNCaP-AI), both calcitriol and 1α(OH)D5 were more effective in the absence of AR transcriptional activity compared to its presence. We have described the characteristics of LNCaP-AI cells previously,36,40 and we have shown that these cells are not growth arrested by culture in CSS or by treatment with bicalutamide (Casodex, AstraZeneca), a competitive inhibitor of AR ligand binding; however, in these cells, CSS or Casodex (AstraZeneca) treatment still inhibits AR transcriptional activity. These cells therefore represent CaP cells that failed first-line hormonal therapy (described in Introduction).

We show that these CRCaP cells do not respond to calcitriol or 1α(OH)D5 because a different effect is now at work, extraordinarily high AR, which suppresses VDR levels. Although growth of these cells is not affected by AWD alone, these treatments still decrease AR transcriptional activity, which stimulates VDR levels; hence, CRCaP LNCaP-AI cells, despite being resistant to AWD and to 1α(OH)D5 individually, are growth inhibited by the combination of these two treatments. Taken together, these results indicate that following the failure of first-line hormonal therapy, 1α(OH)D5 is a good therapeutic agent to prolong the effectiveness of second-line hormonal therapy in CaP cells.

Our data show that the AR is a negative regulator of VDR expression in CRCaP cells but not in castration-sensitive cells so that an increase in AR expression, frequently seen in CRCaP cells, caused a decrease in VDR levels, which prevented 1α(OH)D5’s growth-inhibitory effects (Fig. 6D). The fact that this effect is seen in CRCaP cells but not in the parental castration-sensitive cells indicates that the ability to regulate the VDR is a mechanism acquired during CRCaP development. The AR does not directly affect VDR transcription; however, we show that the cell cycle regulator PHB likely plays an important role in mediating the effect of the AR on VDR expression in CRCaP cells. AR and PHB were earlier shown to regulate each other,28,29 and we now show that PHB regulates VDR expression in CRCaP cells but not in castration-sensitive cells. Therefore, in castration-sensitive cells, although the AR negatively regulates PHB, this does not affect VDR expression, whereas in CRCaP cells, negative regulation of PHB by the AR results in concomitant negative regulation of the VDR by the AR.

An investigation of how PHB affects VDR expression in LNCaP-AI, but not LNCaP, cells is beyond the scope of the present study and will be addressed in future projects. However, it may be noted that a previous report, which showed a suppressive effect of AR on VDR transcriptional activity, suggested that competition for shared coregulators between AR and VDR is a possible mechanism to explain the suppressive effect of androgens on VDR activity.23 In the current study, we do not examine VDR activity but establish that the AR is a negative regulator of VDR expression in CRCaP cells but not in castration-sensitive cells. The effect of AR on VDR levels is likely by a different mechanism involving PHB. PHB is not a transcription factor, but it represses E2F1-mediated gene transcription by recruitment of transcriptional repressors including the nuclear corepressor 1 (NCoR1).25,27 It remains to be seen whether PHB regulation of E2F1 activity, and recruitment of NCoR1, plays a role in its regulation of VDR levels. It may be noted that a 2008 study showed that calcitriol treatment recruits the corepressors NCoR and SMRT to the VDR/RXR complex.47 However, another study showed that overexpression of AR in LNCaP cells induced PHB expression, although the induction was less than 2-fold48; this may be a consequence of the biphasic response of these cells to increased AR and an attempt to slow down the growth of the cells at very high AR.

Furthermore, unlike calcitriol at 100 nM, 1α(OH)D5 at the cytostatic equivalent concentration, 1 µM, did not increase AR transcriptional activity. The significance of the increase in AR transcriptional activity by calcitriol, as seen in LNCaP cells, has been debated. A previous study has noted that the onset of calcitriol-induced G0/G1 arrest in LNCaP and CWR22R cells correlated with the onset of increasing AR expression in response to calcitriol treatment and hypothesized that the antiproliferative actions of calcitriol in AR-positive prostate cancer may be mediated through AR expression.49 While very high levels of androgens, which cause very high levels of AR expression, are known to be antiproliferative,50,51 low-to-medium levels of AR transcriptional activity in CaP cells are associated with high levels of proliferation,51 indicating that the increase in AR transcriptional activity by calcitriol may not be as beneficial as previously suggested.49 On the other hand, this effect may also be an artifact of the cell culture system, as no significant change in serum PSA or free PSA over 8 days was observed in 8 subjects treated with a single dose of 0.5 µg/kg calcitriol.52 However, it is also true that the phase II ASCENT trial did not achieve its primary endpoint for increased PSA response, although there was a significant trend in PSA response rate in the DN-101 arm.44 Therefore, the lack of increase in PSA and AR transcriptional activity as seen in 1α(OH)D5-treated cells compared to calcitriol supports its utility as an antitumor agent.

In summary, we have shown here that the vitamin D analog, 1α(OH)D5, similar to calcitriol, has cytostatic effects in androgen-dependent LNCaP cells. However, unlike calcitriol, 1α(OH)D5 does not increase AR transcriptional activity, indicating a mechanism of action distinct from its parental compound. The cytostatic effects of 1α(OH)D5 are not seen in LNCaP-AI, a CRCaP subline of LNCaP cells, in the presence of androgens. However, AWD, which was ineffective by itself, sensitized LNCaP-AI cells to 1α(OH)D5. These cytostatic effects were mediated by an interaction between the AR and the VDR; in the CRCaP cells, increased expression of the AR repressed VDR expression, and inhibition of the AR stimulated VDR expression and sensitized CaP cells to the growth-inhibitory effects of 1α(OH)D5 mediated by the VDR. These effects are likely mediated by the cell cycle regulator PHB, which stimulated VDR expression in CRCaP cells. Our data show that 1α(OH)D5, together with androgen withdrawal, is likely of therapeutic value to prevent the development of CRCaP.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Pharmacological Treatments

Cells were normally cultured in “regular medium”: RPMI 1640 medium with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) unless otherwise specified. LNCaP cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Androgen-independent clones of LNCaP cells (LNCaP-AI cells)36,37 were obtained by prolonged culture of LNCaP cells in “low androgen medium”: phenol red–free RPMI 1640 with 5% charcoal stripped FBS (CSS, Hyclone, Logan, UT). The SV40-immortalized human prostate epithelial cell line (pRNS-1-1) developed from a normal prostate has been described elsewhere.36,42 These cells had lost expression of the AR while in culture, and stable transfectants of pRNS-1-1 cells expressing vector alone, wild-type, or mutant AR were developed and provided by Dr. XuBao Shi (University of California, Davis).42 Calcitriol and 4,5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were dissolved in 200 proof ethanol, as was 1α(OH)D5, which was synthesized as described elsewhere.14

Analysis of Cell Growth and Death

Flow cytometry

Cells were grown under desired conditions in 100-mm dishes at 0.5 × 106 cells/dish. Flow cytometry was conducted on FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Cells were illuminated with 200 mW of 488-nm light produced by an argon-ion laser. Fluorescence was read through a 630/22-nm band-pass filter (for propidium iodide) or a 530/30-nm band-pass filter (for annexin V–FITC). Data were collected on 20,000 cells as determined by forward and right angle light scatter and stored as frequency histograms; data used for cell cycle analysis were further analyzed using MODFIT (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

MTT Assay

Cells were plated in 24-well plates and treated as indicated. Following treatment, each well was incubated with 25 µL of 5 mg/mL 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5- diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) for 1 hour in a CO2 incubator at 37°C. The medium was aspirated, and 0.5 mL DMSO was added per well. Proliferation rates were estimated by colorimetric assay reading formazan intensity in a plate reader at 562 nm.

Immunoblotting

These techniques were performed as described elsewhere.53,54 Mouse monoclonal anti-AR and antitubulin and antirabbit prohibitin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-PSA and anti-VDR antibodies were from Neomarkers, Lab Vision Corporation (Fremont, CA). Mouse monoclonal antiactin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Transfection

Cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s specifications using 2 µg plasmid DNA. Wild-type AR (pAR0) plasmid had been obtained from Dr. Albert O. Brinkman (Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands).55 The AR mutant plasmid pCEP4-AR(T877A) was developed and provided by Dr. XuBao Shi (University of California, Davis), as has been described elsewhere.56 A human PSA reporter plasmid consisting of the human PSA 5′-flanking region (-631/-1) containing androgen response elements I and II (ARE I and ARE II) tagged to a luciferase construct (hPSA-luc) was also provided by Dr. XuBao Shi (University of California, Davis).

AR Transcriptional Activity

Reporter gene activity was determined by luciferase assay as described by us elsewhere.36 Cells were cotransfected with 2 µg of hPSA-luc with 2 µg of pCMV-βGal using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells grown in complete medium for 24 hours were treated as required for an additional 48 hours. After 48 hours, cell lysates were prepared for performing luciferase assays using a luciferase enzyme assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Each transfection experiment was performed in triplicate on at least 3 separate occasions. Results represent an average of independent experiments with data presented as relative luciferase activity using means of untreated controls as standards.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was performed as described elsewhere.36,37 RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, NY). cDNA synthesis used Moloney murine leukemia virus Reverse Transcriptase (Promega Corporation). The following amplification conditions were used in an MJ PTC-100 thermal cycler (MJ Research, Incline Village, NV): an initial denaturation for 5 minutes at 94°C, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 59°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by a final extension for 10 minutes at 72°C. The following primers were used: α-actin-F: 5′-ACT CTT CCA GCC TTC GTT C-3′, α-actin-R: 5′-ATC TCC TTC TGC ATC CTG TC-3′, hAR-F: 5′-TCC AAA TCA CCC CCC AGG AA-3′, and hAR-R: 5′-GAC ATC TGA AAG GGG GCA TG-3′.

RNA Inhibition

Cells were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s specifications based on established protocols using 50 pmol (stock: 100 nM) of AR siRNA, VDR siRNA, PHB siRNA, or a control (scrambled) siRNA for 48 to 96 hours (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sequences for the siRNA used are the following: anti-AR siRNA sense strands: (A) 5′-CAG UCC CAC UUG UGU CAA A-3′, (B) 5′-CCU GAU CUG UGG AGA UGA A-3′, (C) 5′-GUC GUC UUC GGA AAU GUU A-3′, and (D) 5′-GAC AGU GUC ACA CAU UGA A-3′; VDR siRNA sense strands: (A) 5′-CAU CCG UAG UUC CCU GAA ATT-3′, (B) 5′-CAC GUU CCU UAC UGC AGA ATT-3′, and (C) 5′-GGA ACU CCU GGA AAU AUC ATT-3′; and PHB siRNA sense strands: (A) 5′-CCA UCA CAA CUG AGA UCC U-3′, (B) 5′-GGA AGG AAA CAA AUG UGU A-3′, and (C) 5′-GUG UAU AAA CUG CUG UCA A-3′. Control was a pool of 4 scrambled nonspecific siRNA duplexes. According to the manufacturer, BLAST analysis confirmed at least 4 mismatches with all known human, mouse, and rat genes, and each individual siRNA within this pool was extensively characterized by genome-wide microarray analysis and found to have minimal off-target signatures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. XuBao Shi, Department of Urology, University of California, Davis, for pRNS-1-1 cells stably transfected with an empty vector or wild-type or mutant androgen receptor.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

This work was supported by Award CA133209 from the National Institutes of Health (to P.M.G.).

References

- 1. Edwards J, Bartlett JM. The androgen receptor and signal-transduction pathways in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Part 1: modifications to the androgen receptor. BJU Int. 2005;95:1320-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klotz L. Maximal androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:331-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petrylak D. Therapeutic options in androgen-independent prostate cancer: building on docetaxel. BJU Int. 2005;96 Suppl 2:41-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boehmer A, Anastasiadis AG, Feyerabend S, et al. Docetaxel, estramustine and prednisone for hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a single-center experience. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4481-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Lorenzo G, Buonerba C, Autorino R, De Placido S, Sternberg CN. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: current and emerging treatment strategies. Drugs. 2010;70:983-1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leman ES, Arlotti JA, Dhir R, Getzenberg RH. Vitamin D and androgen regulation of prostatic growth. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:138-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murthy S, Agoulnik IU, Weigel NL. Androgen receptor signaling and vitamin D receptor action in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2005;64:362-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao XY, Ly LH, Peehl DM, Feldman D. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 actions in LNCaP human prostate cancer cells are androgen-dependent. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3290-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beer TM, Myrthue A. Calcitriol in cancer treatment: from the lab to the clinic. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:373-81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson CS, Muindi JR, Hershberger PA, Trump DL. The antitumor efficacy of calcitriol: preclinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2543-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Trump DL, Hershberger PA, Bernardi RJ, et al. Anti-tumor activity of calcitriol: pre-clinical and clinical studies. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89-90:519-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scher HI, Chi KN, De Wit R, et al. Docetaxel (D) plus high-dose calcitriol versus D plus prednisone (P) for patients (Pts) with progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC): results from the phase III ASCENT2 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:450-9 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehta RG, Moriarty RM, Mehta RR, et al. Prevention of preneoplastic mammary lesion development by a novel vitamin D analogue, 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D5. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:212-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mehta R, Hawthorne M, Uselding L, Albinescu D, Moriarty R, Christov K. Prevention of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary carcinogenesis in rats by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D(5). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1836-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehta RG, Hussain EA, Mehta RR, Das Gupta TK. Chemoprevention of mammary carcinogenesis by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D5, a synthetic analog of vitamin D. Mutat Res. 2003;523-524:253-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agus DB, Cordon-Cardo C, Fox W, et al. Prostate cancer cell cycle regulators: response to androgen withdrawal and development of androgen independence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1869-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheng H, Snoek R, Ghaidi F, Cox ME, Rennie PS. Short hairpin RNA knockdown of the androgen receptor attenuates ligand-independent activation and delays tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10613-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choudhury A, Charo J, Parapuram SK, et al. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) inhibits the expression of the Her2/neu gene, upregulates HLA class I and induces apoptosis of Her2/neu positive tumor cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:71-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haag P, Bektic J, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Eder IE. Androgen receptor down regulation by small interference RNA induces cell growth inhibition in androgen sensitive as well as in androgen independent prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;96:251-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peehl DM, Feldman D. Interaction of nuclear receptor ligands with the vitamin D signaling pathway in prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;92:307-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weigel NL. Interactions between vitamin D and androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer cells. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ting HJ, Bao BY, Hsu CL, Lee YF. Androgen-receptor coregulators mediate the suppressive effect of androgen signals on vitamin D receptor activity. Endocrine. 2005;26:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nuell MJ, Stewart DA, Walker L, et al. Prohibitin, an evolutionarily conserved intracellular protein that blocks DNA synthesis in normal fibroblasts and HeLa cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1372-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang S, Nath N, Adlam M, Chellappan S. Prohibitin, a potential tumor suppressor, interacts with RB and regulates E2F function. Oncogene. 1999;18:3501-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang S, Fusaro G, Padmanabhan J, Chellappan SP. Prohibitin co-localizes with Rb in the nucleus and recruits N-CoR and HDAC1 for transcriptional repression. Oncogene. 2002;21:8388-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joshi B, Ko D, Ordonez-Ercan D, Chellappan SP. A putative coiled-coil domain of prohibitin is sufficient to repress E2F1-mediated transcription and induce apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:459-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gamble SC, Odontiadis M, Waxman J, et al. Androgens target prohibitin to regulate proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:2996-3004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gamble SC, Chotai D, Odontiadis M, et al. Prohibitin, a protein downregulated by androgens, represses androgen receptor activity. Oncogene. 2007;26:1757-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dai Y, Ngo D, Jacob J, Forman LW, Faller DV. Prohibitin and the SWI/SNF ATPase subunit BRG1 are required for effective androgen antagonist-mediated transcriptional repression of androgen receptor-regulated genes. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1725-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dart DA, Spencer-Dene B, Gamble SC, Waxman J, Bevan CL. Manipulating prohibitin levels provides evidence for an in vivo role in androgen regulation of prostate tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1157-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peng X, Mehta R, Wang S, Chellappan S, Mehta RG. Prohibitin is a novel target gene of vitamin D involved in its antiproliferative action in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7361-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peng X, Mehta RG. Differential expression of prohibitin is correlated with dual action of vitamin D as a proliferative and antiproliferative hormone in breast epithelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;103:446-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Esquenet M, Swinnen JV, Heyns W, Verhoeven G. Control of LNCaP proliferation and differentiation: actions and interactions of androgens, 1alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, all-trans retinoic acid, 9-cis retinoic acid, and phenylacetate. Prostate. 1996;28:182-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsieh TY, Ng CY, Mallouh C, Tazaki H, Wu JM. Regulation of growth, PSA/PAP and androgen receptor expression by 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the androgen-dependent LNCaP cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;223:141-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen L, Siddiqui S, Bose S, et al. Nrdp1-mediated regulation of ErbB3 expression by the androgen receptor in androgen-dependent but not castrate-resistant prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5994-6003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mikhailova M, Wang Y, Bedolla R, Lu XH, Kreisberg JI, Ghosh PM. AKT regulates androgen receptor-dependent growth and PSA expression in prostate cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;617:397-405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hsieh JT, Wu HC, Gleave ME, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW. Autocrine regulation of prostate-specific antigen gene expression in a human prostatic cancer (LNCaP) subline. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2852-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ghosh PM, Malik SN, Bedolla RG, et al. Signal transduction pathways in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cancer cell proliferation. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:119-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang Y, Kreisberg JI, Bedolla RG, Mikhailova M, deVere White RW, Ghosh PM. A 90 kDa fragment of filamin A promotes Casodex-induced growth inhibition in Casodex-resistant androgen receptor positive C4-2 prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:6061-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang Y, Mikhailova M, Bose S, Pan CX, deVere White RW, Ghosh PM. Regulation of androgen receptor transcriptional activity by rapamycin in prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene. 2008;27:7106-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi XB, Xue L, Tepper CG, et al. The oncogenic potential of a prostate cancer-derived androgen receptor mutant. Prostate. 2007;67:591-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beer TM, Ryan CW, Venner PM, et al. Intermittent chemotherapy in patients with metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer: results from ASCENT, a double-blinded, randomized comparison of high-dose calcitriol plus docetaxel with placebo plus docetaxel. Cancer. 2008;112:326-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brawer MK. Recent progress in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer with intermittent dose-intense calcitriol (DN-101). Rev Urol. 2007;9:1-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma Y, Yu WD, Kong RX, Trump DL, Johnson CS. Role of nongenomic activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathways in 1,25D3-mediated apoptosis in squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8131-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mehta RG. Stage-specific inhibition of mammary carcinogenesis by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D5. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2331-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sanchez-Martinez R, Zambrano A, Castillo AI, Aranda A. Vitamin D-dependent recruitment of corepressors to vitamin D/retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3817-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Urbanucci A, Waltering KK, Suikki HE, Helenius MA, Visakorpi T. Androgen regulation of the androgen receptor coregulators. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bao BY, Hu YC, Ting HJ, Lee YF. Androgen signaling is required for the vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition in human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:3350-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lin HK, Yeh S, Kang HY, Chang C. Akt suppresses androgen-induced apoptosis by phosphorylating and inhibiting androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7200-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hofman K, Swinnen JV, Verhoeven G, Heyns W. E2F activity is biphasically regulated by androgens in LNCaP cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;283:97-101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beer TM, Garzotto M, Park B, et al. Effect of calcitriol on prostate-specific antigen in vitro and in humans. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2812-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ghosh PM, Bedolla R, Mikhailova M, Kreisberg JI. RhoA-dependent murine prostate cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis: role of protein kinase Czeta. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2630-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ghosh PM, Mikhailova M, Bedolla R, Kreisberg JI. Arginine vasopressin stimulates mesangial cell proliferation by activating the epidermal growth factor receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F972-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brinkmann AO, Blok LJ, de Ruiter PE, et al. Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation and function. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;69:307-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shi XB, Ma AH, Xia L, Kung HJ, de Vere White RW. Functional analysis of 44 mutant androgen receptors from human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1496-502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.