Abstract

The stress-induced extracytoplasmic sigma factor E (SigE) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis shows increased expression after heat shock, sodium dodecyl sulfate treatment, and oxidative stress, as well as after phagocytosis in macrophages. We report that deletion of sigE results in delayed lethality in mice without a significant reduction of bacterial numbers in lungs.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes 13 sigma factors belonging to the σ70 class of σ factors (3, 8). SigA and SigB are the principal sigma factors, and the other 11 are alternative sigma factors, with all but SigF considered to be extracytoplasmic function σ factors, mediating interactions of the bacterium with the extracellular environment. The sigE gene is conserved in mycobacteria but is not essential for growth in vitro (18). Deletion of sigE (ΔsigE) results in increased susceptibility to heat shock and chemical stress (6, 15, 18). Expression of sigE increases after phagocytosis by human and mouse macrophages (9, 10). In the absence of sigE, the viability of M. tuberculosis in both activated and unactivated macrophages is decreased (15). Finally, deletion of sigE has been shown by microarray analysis to result in the downregulation of genes which encode transcriptional regulators, fatty acid metabolism enzymes, and heat shock proteins (15).

In our laboratory we have characterized a number of sigma factors in terms of their responses to stress, their effects on the expression of other genes, and their phenotypes in mice (2, 5, 11). We report here our findings with C3H/HeJ mice infected by aerosol with an M. tuberculosis CDC1551 sigE deletion mutant compared to mice infected with wild-type or sigE-complemented M. tuberculosis CDC1551 (7). Utilizing a targeted-disruption strategy based on the vector pCK0686, which contains a hygromycin resistance cassette flanked by multiple cloning sites (MCS) (11), we cloned a left-flank PCR product with 1,943 bp proximal to the sigE gene (MT1259/Rv1221) and a nonoverlapping right-flank product of 1,889 bp into the MCS, resulting in the deletion of the central region of sigE from the targeting vector. Only 19 bp of the 5′ end and 392 bp of the 3′ end of the sigE gene remained in place, while a central 360 bp was deleted. The resulting plasmid, pCK0699, was then used to transform M. tuberculosis CDC1551 in a two-step selection process, with Southern blotting used to confirm allelic exchange. A complemented sigE mutant strain was created by cloning a 2,930-bp M. tuberculosis CDC1551 genomic fragment including the coding region as well as the regulatory region of the sigE gene and 215 bp downstream into an L5 phage-based integration-proficient vector for mycobacteria, pMH94 (12), and then transforming the M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant with this vector. Groups of inbred C3H/HeJ or BALB/c-severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were infected by aerosol with matched inocula of the wild-type, knockout, or complemented strain, which routinely implant ∼100 organisms in the lungs. For CFU organ burden determinations, groups of five mice were sacrificed at day 1 and at 4, 12, and 20 weeks and lung and spleen CFU counts were enumerated. For time-to-death studies, groups of 10 mice were infected with matched inocula and monitored daily for mortality.

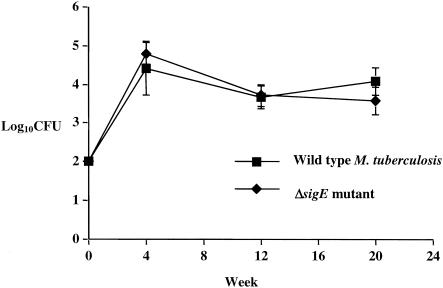

The M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant showed a CFU organ burden in C3H/HeJ mouse lungs that was similar to the pattern observed with wild-type infection (Fig. 1). The complemented ΔsigE mutant gave lung CFU counts that closely matched those of the wild type and the ΔsigE mutant (log10 CFU counts at 12 and 16 weeks of 3.67 ± 0.29 and 4.06 ± 0.3, respectively). Spleen counts for C3H/HeJ mice showed that all three strains were absent in the spleens on day 1 following aerosol infection but then disseminated from lungs to the spleen by 4 weeks at equivalent levels (log10 spleen CFU counts of 3.54 ± 0.83, 2.08 ± 1.9, and 2.33 ± 2.31 for the wild type, ΔsigE mutant, and complemented ΔsigE mutant, respectively). Thus CFU organ burden studies of immunocompetent C3H/HeJ mice showed that the M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant and the complemented strain had virulence equivalent to that of the wild-type parental strain, CDC1551.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of CFU of wild-type, sigE-deleted, and sigE-complemented M. tuberculosis CDC1551 in lungs of C3H/HeJ mice after aerosol infection.

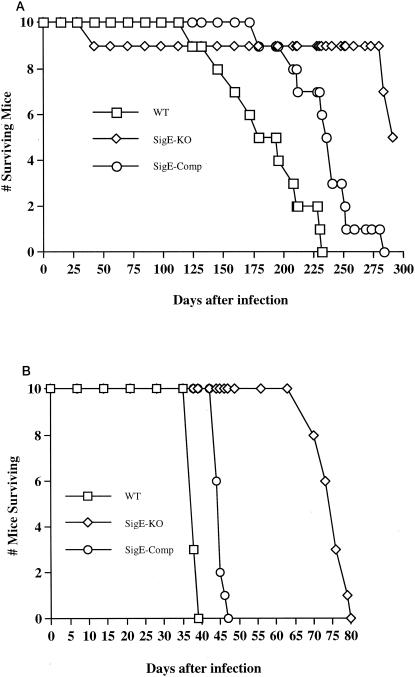

In contrast, time-to-death analysis showed that 50% of C3H/HeJ mice infected with wild-type and complemented M. tuberculosis died by days 194 and 236, respectively, whereas 50% of mice infected with the ΔsigE mutant survived 291 days (Fig. 2A). Remarkably, all BALB/c-SCID mice infected with wild-type or complemented bacilli died by day 39 or 47, whereas none of the mice infected with the mutant died until day 70 (Fig. 2B). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that times to death for both immunocompetent C3H/HeJ and immunocompromised BALB/c-SCID mice infected with the ΔsigE mutant were significantly prolonged compared to those for mice infected with the wild-type or complemented strain (P < 0.001). In immunocompetent mice, but not immunocompromised mice, the complemented strain exhibited a phenotype intermediate between the wild-type and the knockout phenotypes. The difference in time to death between wild-type and complemented bacilli was statistically significant, suggesting that, as measured in this assay, complementation may have been only partial. Thus, despite achieving a persistent, high-organ-burden infection in mouse lungs, the M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant was found to be significantly attenuated by time-to-death analysis.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of time to death after aerosol infection with wild-type, sigE-deleted, and sigE-complemented M. tuberculosis CDC1551. Immunocompetent C3H/HeJ mice (A) showed a delayed time to death after infection with the knockout mutant (SigE-KO) compared to infection with the wild type (WT). BALB/c mice with the SCID mutation (B) succumbed by day 39 or 47 after infection with wild-type or sigE-complemented bacilli, respectively.

We have previously observed a similar virulence phenotype with the M. tuberculosis ΔsigH mutant, in which high organ CFU counts in both mutant and wild-type bacilli were observed but animals infected with the mutant showed a significant delay in time to death (11). One distinction from the ΔsigH mutant is that there is a significant delay in the time to death for SCID mice as well as for immunologically intact mice after infection with the ΔsigE mutant bacilli. This may suggest that the ΔsigE tubercle bacilli are more susceptible to innate, T-cell-independent killing than are the ΔsigH organisms. Interestingly, for the M. tuberculosis ΔsigH mutant, both CD4 and CD8 cell recruitment to the lung was reduced in mouse tissues at 4 weeks; similarly, histological sections showed a corresponding delay in disease progression in mouse tissues on infection with the ΔsigH mutant (11). We have designated this phenotype of bacterial persistence with reduced host mortality the immunopathology (imp) defect. Although the immunopathology phenotype has been observed upon mouse infection with both the M. tuberculosis ΔsigH and now the ΔsigE mutants, it is significant that functional redundancy does not appear to account for the similar animal phenotypes. Microarray analysis of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigH mutant suggests that the sigma factor governs a redox stress response regulon, with several thioredoxins and thioredoxin reductases showing relative underexpression in the ΔsigH mutant compared with expression in the wild type (11). In contrast, the M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant sigma factor has been reported to govern a more generalized stress response regulon (15), and inspection of the genes putatively governed by these sigma factors reveals few common genes. Interestingly, the impaired survival of the M. tuberculosis ΔsigE mutant within macrophages reported by Manganelli et al. (15) does not appear to extend to a survival defect in lung and spleen tissues in C3H/HeJ mice. Recently, several non-sigma factor M. tuberculosis mutants, including the M. tuberculosis ΔRD1 mutant (13) and ΔwhiB3 mutant (17), have been reported; these mutants show mouse infection patterns similar to the immunopathology phenotype observed in the M. tuberculosis ΔsigH and ΔsigE mutants. As both the RD1 region (14) and the whiB-like gene family (4, 16) have been implicated in gene regulation, one might speculate that the immunopathology phenotype is an attenuation pattern associated with aberrant gene regulation pathways and an inability to adapt to key stimuli during growth in vivo in live animal hosts. While further research will be important in order to understand the basis of the immunopathology defect, this class of M. tuberculosis mutants has attractive features as live, attenuated vaccines against tuberculosis in view of their reduced lethality but significant persistence in the host—factors which may be important in the maintenance of protective immunity (1).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AI 36973, AI 37856, and AI 43846 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandt, L., J. Feino Cunha, A. W. Olsen, B. Chilima, P. Hirsch, R. Appelberg, and P. Andersen. 2002. Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:672-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, P., R. E. Ruiz, Q. Li, R. F. Silver, and W. R. Bishai. 2000. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the alternate sigma factor gene, sigF. Infect Immun. 68:5575-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis, N. K., and K. F. Chater. 1992. The Streptomyces coelicolor whiB gene encodes a small transcription factor-like protein dispensable for growth but essential for sporulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232:351-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMaio, J., Y. Zhang, C. Ko, D. B. Young, and W. R. Bishai. 1996. A stationary-phase stress-response sigma factor from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2790-2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes, N. D., Q. L. Wu, D. Kong, X. Puyang, S. Garg, and R. N. Husson. 1999. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic sigma factor involved in survival following heat shock and oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 181:4266-4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann, R. D., D. Alland, J. A. Eisen, L. Carpenter, O. White, J. Peterson, R. DeBoy, R. Dodson, M. Gwinn, D. Haft, E. Hickey, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, L. A. Umayam, M. Ermolaeva, S. L. Salzberg, A. Delcher, T. Utterback, J. Weidman, H. Khouri, J. Gill, A. Mikula, W. Bishai, W. R. Jacobs Jr., J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Whole-genome comparison of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical and laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 184:5479-5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez, J. E., J. M. Chen, and W. R. Bishai. 1997. Sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber. Lung Dis. 78:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham, J. E., and J. E. Clark-Curtiss. 1999. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNAs synthesized in response to phagocytosis by human macrophages by selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11554-11559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen-Cain, D. M., and F. D. Quinn. 2001. Differential expression of sigE by Mycobacterium tuberculosis during intracellular growth. Microb. Pathog. 30:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaushal, D., B. G. Schroeder, S. Tyagi, T. Yoshimatsu, C. Scott, C. Ko, L. Carpenter, J. Mehrotra, Y. C. Manabe, R. D. Fleischmann, and W. R. Bishai. 2002. Reduced immunopathology and mortality despite tissue persistence in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking alternative sigma factor, SigH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:8330-8335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee, M. H., L. Pascopella, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and G. F. Hatfull. 1991. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:3111-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis, K. N., R. Liao, K. M. Guinn, M. J. Hickey, S. Smith, M. A. Behr, and D. R. Sherman. 2003. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis mimics bacille Calmette-Guerin attenuation. J. Infect. Dis. 187:117-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahairas, G., P. Sabo, M. Hickey, D. Singh, and C. Stover. 1996. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1274-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manganelli, R., M. I. Voskuil, G. K. Schoolnik, and I. Smith. 2001. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor σE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 41:423-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soliveri, J. A., J. Gomez, W. R. Bishai, and K. F. Chater. 2000. Multiple paralogous genes related to the Streptomyces coelicolor developmental regulatory gene whiB are present in Streptomyces and other actinomycetes. Microbiology 146:333-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steyn, A. J., D. M. Collins, M. K. Hondalus, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., R. P. Kawakami, and B. R. Bloom. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis WhiB3 interacts with RpoV to affect host survival but is dispensable for in vivo growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:3147-3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu, Q. L., D. Kong, K. Lam, and R. N. Husson. 1997. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic function sigma factor involved in survival following stress. J. Bacteriol. 179:2922-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]