Abstract

Objective

To explore the positive and negative effects of medical tourism on the economy, health staff and medical costs in Thailand.

Methods

The financial repercussions of medical tourism were estimated from commerce ministry data, with modifications and extrapolations. Survey data on 4755 foreign and Thai outpatients in two private hospitals were used to explore how medical tourism affects human resources. Trends in the relative prices of caesarean section, appendectomy, hernia repair, cholecystectomy and knee replacement in five private hospitals were examined. Focus groups and in-depth interviews with hospital managers and key informants from the public and private sectors were conducted to better understand stakeholders’ motivations and practices in connection with these procedures and learn more about medical tourism.

Findings

Medical tourism generates the equivalent of 0.4% of Thailand’s gross domestic product but has exacerbated the shortage of medical staff by luring more workers away from the private and public sectors towards hospitals catering to foreigners. This has raised costs in private hospitals substantially and is likely to raise them in public hospitals and in the universal health-care insurance covering most Thais as well. The “brain drain” may also undermine medical training in future.

Conclusion

Medical tourism in Thailand, despite some benefits, has negative effects that could be mitigated by lifting the restrictions on the importation of qualified foreign physicians and by taxing tourists who visit the country solely for the purpose of seeking medical treatment. The revenue thus generated could then be used to train physicians and retain medical school professors.

ملخص

الغرض

التعرّف على التأثيرات الإيجابية والسلبية للسياحة العلاجية على الاقتصاد، والعاملين الصحيين، والتكاليف الطبية في تايلاند.

الطريقة

أُجرِى تقييم للعواقب المالية للسياحة العلاجية من معطيات وزارة التجارة، مع إجراء تعديلات واستقراءات على تلك المعطيات. وأُجرِى مسح للمعطيات ضم 4755 مريضاً خارجياً من الأجانب والتايلانديين في مستشفيين خاصين لاستكشاف تأثير السياحة العلاجية على الموارد البشرية. وفُحِصَت اتجاهات الأسعار النسبية لجراحة القيصرية، واستئصال الزائدة، وإصلاح الفتق، واستئصال المرارة، واستبدال الركبة في خمسة مستشفيات خاصة. واستُخدمت مجموعات التركيز وأُجرِيت مقابلات متعمقة مع مدراء المستشفيات والجهات الرئيسية المعنية بالمعلومات من القطاعين العام والخاص لتوسيع الإدراك بدوافع وممارسات أصحاب المصلحة في ما يتصل بتلك الإجراءات والتعرّف على نحو أفضل بالسياحة العلاجية.

النتائج

تُدّر السياحة العلاجية ما يعادل 0.4% من إجمالي الناتج المحلي في تايلاند لكنها تفاقم من نقص العمالة الطبية نتيجة لإغراء المزيد من العمّال على ترك القطاعين الخاص والعام والعمل في المستشفيات التي تقدّم خدماتها للأجانب. وهذا أدى إلى ارتفاع هائل في التكاليف في المستشفيات الخاصة ومن المرجّح ارتفاع التكاليف في المستشفيات العامة والتأمين الصحي الشامل الذي يغطّي غالبية التايلانديين.

الاستنتاج

مع أن للسياحة العلاجية في تايلاند بعض المزايا لكن لها تأثيرات سلبية يمكن التخفيف منها عن طريق رفع القيود عن استيراد الأطباء الأجانب المؤهلين وفرض الضرائب على السيّاح الذين يزورون البلد بحثاً عن العلاج الطبي فقط. ومن ثمَّ يمكن الاستفادة من الموارد المالية المُتحصَّـل عليها في تدريب الأطباء والحفاظ على أساتذة الكليات الطبية.

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner les effets positifs et négatifs du tourisme médical sur l’économie, le personnel de santé et les coûts médicaux en Thaïlande.

Méthodes

Les répercussions financières du tourisme médical ont été estimées à partir de données émanant du ministère du Commerce, avec des modifications et des extrapolations. Les données d’une enquête réalisée auprès de 4 755 patients ambulatoires étrangers et thaïlandais dans deux hôpitaux privés ont été utilisées afin d’étudier l’impact du tourisme médical sur les ressources humaines. Les tendances des tarifs relatifs de la césarienne, de l’appendicectomie, de la réparation de hernies, de la cholécystectomie et de l’arthroplastie du genou dans cinq hôpitaux privés ont été examinées. Des groupes cibles et des entrevues approfondies avec des directeurs d'hôpital et des témoins privilégiés des secteurs public et privé ont été organisés afin de mieux comprendre les motivations et les pratiques des parties prenantes liées à ces interventions et de renforcer les connaissances sur le tourisme médical.

Résultats

Le tourisme médical génère l’équivalent de 0,4% du produit intérieur brut thaïlandais, mais il exacerbe la pénurie de personnel médical en détournant de plus en plus de travailleurs des secteurs privé et public au profit des hôpitaux traitant les étrangers. Cela se traduit par une augmentation substantielle des coûts dans les hôpitaux privés et il est probable qu’il en aille de même au niveau des hôpitaux publics et de l'assurance santé universelle qui prend en charge la plupart des Thaïlandais. La «fuite des cerveaux» est également susceptible de porter atteinte à la formation médicale dans le futur.

Conclusion

Le tourisme médical en Thaïlande, en dépit de certains avantages, a des effets négatifs qui pourraient être atténués par une levée des restrictions appliquées à l’importation de médecins étrangers qualifiés et par une taxe visant les touristes qui ne visitent le pays qu’en vue de bénéficier d’un traitement médical. Le chiffre d’affaires qui serait ainsi généré pourrait ensuite servir à former des médecins et à retenir les professeurs des facultés de médecine.

Resumen

Objetivo

Analizar los efectos positivos y negativos que tiene el turismo médico en la economía, el personal sanitario y los gastos médicos de Tailandia.

Métodos

Las repercusiones económicas del turismo médico se calcularon a partir de los datos del Ministerio de comercio, con diversas modificaciones y extrapolaciones. Para investigar cómo afecta el turismo médico a los recursos humanos se emplearon los datos de una encuesta realizada a 4 755 pacientes ambulatorios tailandeses y extranjeros en dos hospitales privados. Se analizaron las tendencias de los precios relacionados con la cesárea, la apendicectomía, la herniorrafia, la colecistectomía y la artroplastia de rodilla en cinco hospitales privados. Se crearon grupos de investigación cualitativa y se realizaron entrevistas minuciosas a los directores de hospital y a los informadores clave procedentes del sector privado y público para entender mejor los motivos y las prácticas de los interesados relacionados con estos procedimientos y, de este modo, aprender más acerca del turismo médico.

Resultados

El turismo médico genera el equivalente al 0,4% del producto interior bruto de Tailandia, si bien ha agravado la falta de personal médico al tentar a muchos trabajadores procedentes de los sectores público y privado para que trabajen en hospitales orientados a los extranjeros. Esto ha provocado un aumento sustancial de los costes en los hospitales privados y probablemente también conllevará un aumento de los mismos en los hospitales públicos y en el seguro sanitario universal del que se benefician la mayoría de los tailandeses. Esta «fuga de cerebros» también podría perjudicar a la formación médica futura.

Conclusión

El turismo médico en Tailandia, a pesar de ofrecer ciertos beneficios, presenta también efectos negativos que podrían mitigarse reduciendo las restricciones para la importación de personal médico cualificado procedente del extranjero y gravando con impuestos a los turistas que visiten este país con el único propósito de someterse a un tratamiento médico. Los ingresos que se obtuvieran de este modo podrían emplearse en la formación de médicos y para que los catedráticos permanecieran en la Facultad de Medicina.

Резюме

Цель

Исследовать положительное и отрицательное влияние медицинского туризма на экономику, медицинский персонал и стоимость медицинского обслуживания в Таиланде.

Методы

Финансовый эффект от медицинского туризма оценивался по данным Министерства торговли с применением модификаций и экстраполяции. Для исследования воздействия медицинского туризма на персонал использовались данные опроса 4 755 таиландских и иностранных пациентов, получавших амбулаторное лечение в двух частных больницах. Исследовалась динамика относительных цен на проведение кесарева сечения, аппендэктомии, оперативного лечения грыжи, холецистэктомии и замены коленного сустава в пяти частных больницах. Чтобы лучше понять мотивацию и практику участников в связи с этими процедурами и больше узнать о медицинском туризме, проводились фокус-группы и подробные интервью с руководящими работниками больниц и ключевыми информаторами.

Результаты

Медицинский туризм генерирует доход, эквивалентный 0,4% валового внутреннего продукта Таиланда. В то же время серьезной проблемой является дефицит медицинских кадров, вызванный переманиванием работников из медицинских учреждений частного и общественного секторов в больницы, обслуживающие иностранцев. Это привело к значительному росту затрат в частных больницах и, по-видимому, будет способствовать их повышению в государственных больницах и системе всеобщего медицинского страхования, охватывающей большинство таиландцев. Кроме того, в будущем «утечка мозгов» может привести к снижению уровня подготовки медицинских кадров.

Вывод

Медицинский туризм в Таиланде, несмотря на некоторые положительные стороны, порождает негативный эффект, который можно было бы снизить путем ужесточения ограничений на въезд квалифицированных иностранных врачей и усиления налогообложения туристов, посещающих страну исключительно в лечебных целях. Доход, накопленный в результате этого, мог бы быть использован для организации повышения квалификации врачей и стабилизации кадров преподавателей медицинских учебных заведений.

摘要

目的

旨在探讨泰国医疗旅游对经济、医务人员和医疗成本的正面和负面影响。

方法

根据商务部的数据加以修改和推断,估测了医疗旅游对金融的影响。从两家私立医院4755名外籍和泰国门诊病人所得的数据来探索医疗旅游如何影响人力资源。同时还审查了五家私立医院剖宫产、阑尾切除术、疝气修补、胆囊切除术和膝关节置换术相对价格的变化趋势。此外,通过进行分组座谈会并与公共和私营部门的医院负责人和知情人进行深度访谈,更好地了解与就医流程有关的利益相关者的动机和做法以及更多地了解医疗旅游。

结果

医疗旅游带来了相当于泰国国内生产总值0.4%的价值,但是更多医务人员从私有和公共部门流向为外国人服务的医院,也在一定程度上加剧了医务人员的短缺。这导致私立医院医疗成本大幅度增加,并且可能引起公立医院医疗成本增加以及覆盖大多数泰国人的全民医疗保险成本增加。“人才外流”还可能破坏未来的医疗培训。

结论

泰国的医疗旅游尽管有一些好处,但也有负面影响,负面影响可通过取消对引进合格外国医生的限制以及向那些仅为治疗而前往本国的旅游者征税的方法予以缓解。由此所产生的收入可用来培训医师和留住医学院教授。

Introduction

Unlike general tourists needing medical attention, medical tourists are people who cross international borders for the exclusive purpose of obtaining medical services. Medical tourism has increased in part because of rising health-care costs in developed countries, cross-border medical training and widespread air travel. The medical tourism industry has been growing worldwide. It involves about 50 countries in all continents and several Asian countries are clearly in the lead. In Asia, medical tourism is highest in India, Singapore and Thailand. These three countries, which combined comprised about 90% of the medical tourism market share in Asia in 2008,1 have invested heavily in their health-care infrastructures to meet the increased demand for accredited medical care through first-class facilities.2,3

In 2007, Thailand provided medical services for as many as 1.4 million foreign patients, including medical tourists, general tourists and foreigners working or living in Thailand or its neighbouring countries. If we assume that about 30% of all foreign patients that year were medical tourists – a conservative figure by comparison with the Boston Consulting Group’s estimate of 50% in 20064 – the total number would have been about 420 000. This was more than in Singapore, formerly reputed to be the leading Asian medical tourist destination and the “medical hub of Asia”.5

Although medical tourists are still a small fraction of the 1.5 million foreigners who receive medical care in Thailand, they are the tourist group most likely to affect the country in a major way. Unlike general tourists and expatriates, medical tourists are increasing at a rapid pace – from almost none to 450 000 a year in less than a decade. Moreover, medical tourists tend to seek more intensive and costly treatments than other foreign patients, as a result of which their effect on the country is more profound.

In this paper Thailand is used as a case study to examine the main effects of medical tourism on a country’s economy and health system. The final section of the paper discusses policy implications and provides some policy recommendations.

Methods

This paper focuses on medical tourism. However, singling out data for medical tourists is difficult because Thailand breaks their data down into Thais and foreigners but not into foreigners who are medical tourists and other foreigners seeking medical care. Another reason that these two groups are usually lumped together is that most foreign patients behave similarly when seeking health care, share similar views regarding patient’s rights, and have similar health-care needs. Once they fall ill and need health care, they tend to have similar demands and requirements. It must be borne in mind, however, that the fact that the data for all foreigners are lumped together makes the mean values obtained for the average medical tourist (e.g. in terms of physician time required) usually higher than the mean values obtained for the average foreign patient.

The study is divided into three parts. The first part estimates the effects of medical tourism on the Thai economy in terms of revenues from medical services and value added gained from the activities of patients and the companions travelling with them before and after medical treatment. In general, revenues from either medical services or tourist activities include the costs of services and materials, some of which, especially new drugs and advanced equipment, are imported. Hence, the domestic value added (the revenue left after subtracting the cost of imported materials) is a better indicator of the net economic benefit of medical tourism than total revenues. Theoretically, however, the value added figures presented here are overestimated, especially with health-care providers’ income included in the calculations. This is because without foreign patients, these providers would probably spend more time with Thai patients and some positive value added would still be generated (even if lower than the value added generated from serving foreign patients) along with improvements in health status and social welfare for Thai citizens.

The estimated effects of medical tourism were partly based on data furnished by Thailand’s Ministry of Commerce, with some modifications and extrapolations to fit various scenarios and assumptions that we considered more realistic. The estimations and projections were made in two parts: (i) revenue and value added from medical services provided to foreign patients, and (ii) revenue and value added from the activities of medical tourists and their travelling companions, including before and after the medical treatment.

The methods (with main scenarios and assumptions) used to make estimates and projections are as follows:

The study estimates revenues and value added from medical tourism in 2008–2012 under high- and low-growth scenarios, as follows:

High growth: The number of foreign patients grows at a yearly rate of 16%. The assumption was based on the average geometric growth rate of foreign patients in 2001–2007 (figures from the Ministry of Commerce), a period in which medical tourism in Thailand expanded rapidly.

Low growth: The number of foreign patients grows at one half the average annual rate of 2.5% seen in 2005–2007 because of potential competition or changes in Thai government policies. This scenario rests on the assumption that the rate of growth of foreign patients will continue to fall to only half of the growth rate in 2005–2007, a period during which, according to the Ministry of Commerce, the rate was the lowest in 7 years.

The average revenue per foreign patient in 2006 and 2007 was based on figures from the Department of Export Promotion of Thailand’s Ministry of Commerce. The revenues for 2008 and later were assumed to grow at 10% per year on average. This growth rate is slightly lower than the 16% average growth rate in medical service charges for high-end hospitals (figure obtained from interviews with hospital administrators) that resulted from the expected increase in competition in both domestic and international markets.

The value added (including wages) of medical services was assumed to be 66.7% of the gross revenue, lower than the implied rate of 91–92% estimated for Singapore (Ministry of Trade and Industry of Singapore, The Health Care Services Working Group, n.d.). This is likely to be an overestimation since expensive medical equipment and medicines are being imported and Thai hospitals tend to charge lower medical service fees than their counterparts in Singapore. At the same time, the value added (including wages) should be greater than 50%, since labour costs for public hospitals account for approximately 50% or more of the total cost of health-care services6,7 and private hospitals, especially those attending medical tourists, should have higher labour costs than most public hospitals.

The average revenue from hotels and tourism per foreign patient in the base year (2008) was estimated at 10% of total medical charges. This rather low figure reflects the fact that approximately 60% of all foreign patients reside in Thailand and another 10% are tourists that become sick while visiting the country. Only the remaining 30% of foreign patients are medical tourists who travel to Thailand explicitly to seek medical services and who generate extra revenue from hotel charges and tourism. For these patients, non-medical expenses, which would apply to the periods spent outside the hospital before and after treatment, were assumed to be 33.3% of their medical charges (including hospital room and meals).

The average revenue from hotel and tourist charges for the individuals accompanying the medical tourist was assumed to be 15% of the total medical charges in 2008, other assumptions being that only three fourths of the patients would have one person accompanying them (information obtained from interviews with hospital administrators and medical tour companies) and that each travelling companion would spend twice as much on hotels and tourism as the patient. Medical tourists almost certainly spend less on hotels and tourism than the individuals accompanying them. However, these individuals are not likely to spend much more than the patients themselves, since they spend little time on their own when caring for the patients.

Value added from tourism was assumed to be 50% of revenues (as suggested by Singapore’s estimates of 63.5–66.7%, but wages in Singapore are significantly higher than in Thailand) and to increase by 10% in 2008 (due to the high inflation rate that year) and by 6.7% per year in the following years.

The second part of the paper estimates the effects of medical tourism in Thailand on health service prices and on medical staffing, particularly on the demand for physicians. To realistically estimate foreign patients’ demand for physicians, we collected information on the time that foreign and Thai outpatients spent with physician in two private hospitals. One was the flagship of a major network of high-end facilities whose foreign customers are primarily non-Asian; the other was a hospital where most foreign customers were from southern Asia and the Middle East. We hypothesized that foreign patients would spend longer on average with the physician, partly because of the demands of communicating in English or through interpreters and because non-Asian foreign patients tend to ask more questions and engage in more interactive discussions with physicians than Thai patients.

In the first hospital we collected data on approximately 4000 outpatients who visited 19 different physicians in various departments (orthopaedics, neurology, gastroenterology, obstetrics and gynaecology, surgery, cardiology, otolaryngology and internal medicine). In the second hospital we collected data from 755 patients who visited 6 physicians. We then used multiple regression to control treatment variability for each physician in different departments. We distinguished Thai from foreign patients on the basis of first and last names and the languages in which names were entered in the medical record, and we used a dummy variable for the patient’s nationality. We also employed 18 and 5 physician-specific dummy variables, respectively, to account for the fixed effect of each physician, which could reflect both the physician’s self-effect and the department-specific effect.

The last part of the paper measures trends in the relative prices of health-care services for Thai patients in private hospitals. We requested empirical price data for 2003–2008 from both private hospitals targeting primarily foreign patients and from hospitals that focus on Thai patients. A focus group composed of surgeons and hospital administrators (also physicians) from leading private hospitals chose five “representative” surgical procedures: caesarean section, appendectomy, hernia repair, cholecystectomy and knee replacement. These were conventional treatments with little price variation among patients and drugs were not a significant part of their costs because we excluded cases with complications. We then explored the changes in total charges per patient (or for a typical patient under a typical service package) over the preceding 5 years (or the most recent years for which data were available).

Real price changes for public hospitals, whose service prices are set by the government, are roughly reflected by the per capita government budget for various public schemes under the overarching universal health-care coverage scheme.

Results

Effects on the economy

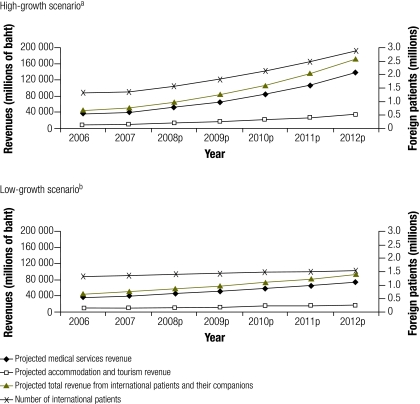

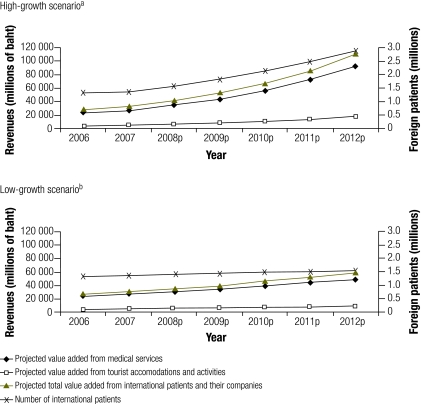

In 2008, medical tourism in Thailand generated 46 to 52 billion baht (1 United States dollar [US$] = 30 baht) of revenue from medical services plus 12 to 13 billion baht from related tourism. This makes for total revenues of 58 to 65 billion baht (Fig. 1), which translate into a value added (Fig. 2) of 31 to 35 billion baht from medical services plus 5.8 to 6.5 billion baht from tourism. This amounts to a total value added of 36.8 to 41.6 billion baht or 0.4% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Under various scenarios, the value added from medical tourism is projected to reach between 59 and 110 billion baht in 2012.

Fig. 1.

Projected revenue generated by foreign patients: high- and low-growth scenarios, Thailand, 2008–2012

p, projected.

a Scenario in which the number of foreign patients in Thailand is assumed to grow at a faster rate than at present (16% per year).

b Scenario in which the number of foreign patients in Thailand is assumed to grow at half the average annual rate of 2.5% seen in 2005–2007 (possible reasons: greater competition, the establishment of hospitals overseas, or new government regulations).

Fig. 2.

Projected value added generated by foreign patients: high- and low-growth scenarios, Thailand, 2008–2012

p, projected.

a Scenario in which the number of foreign patients in Thailand is assumed to grow at a faster rate than at present (16% per year).

b Scenario in which the number of foreign patients in Thailand is assumed to grow at half the average annual rate of 2.5% seen in 2005–2007 (possible reasons: greater competition, the establishment of hospitals overseas, or new government regulations).

Staffing and health service prices

This section estimates the effects of medical tourism in Thailand on medical staff, especially physicians, who are in shortest supply,8,9 and on the price of health-care services in private hospitals.

Foreign patient demand for physicians

In the first hospital, the average time physicians spent per outpatient visit was 33 minutes – 32 for a Thai outpatient (based on the predicted regression result of the time the median physician, i.e. the tenth physician out of the 19, spent with a typical Thai patient) and 33.4 for a typical foreign patient. Despite its high statistical significance (t = 2.398; P = 0.017 for the nationality dummy variable), the difference is rather small (1.4 minutes). This could result from self-selection bias, since the majority of Thai customers visiting this hospital are wealthy and may resemble non-Asians in their health-care-seeking behaviour.

In the second hospital, the median physician spent an average of 29.8 minutes per visit with a typical foreign outpatient, compared with 25.3 minutes with a typical Thai outpatient. This 4.5-minute difference was also statistically significant (t = 3.725; P = 0.000).

The results from both hospitals, despite being slightly different, suggest that the time spent by each physician on medical tourists greatly exceeds previous projections.10–12 Thus, a full-time physician would be able to see only 14 to 16 foreign patients per day on average rather than 40 to 48 (an average of 10 to 12 minutes per patient), as estimated by Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert.10

The results from these the two hospitals suggest that the actual demand for physicians may be three times as high as estimated by Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert. Therefore, if the more realistic figures from our research, which are about three times higher than Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert’s estimate, are applied in conjunction with these authors’ other assumptions (e.g. that international patients will represent 14–16% of all patients in 2009–2011 and 10–12% in 2012–2015), the additional demand for physicians could climb to 369–543 in 2008–2009 and to 528–909 in 2014–2015 (Table 1). Furthermore, most of the physicians demanded by foreigners are specialists who have trained and practised for at least 10 years on average.

Table 1. Projected demand for physicians by foreign patientsa in Thailand, 2003–2015.

| Year | Foreign patient visits per year (millions) |

Total no of outpatient equivalent visits per year (millions) (3)c | Physician demand by foreigners |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatientsb (1) | Inpatients (2) | Projectiond (4) | Revised projectione (5) | ||

| 2001 | 0.61 | 0.030 | 1.22 | – | – |

| 2002 | 0.82 | 0.041 | 1.64 | – | – |

| 2003p | 1.26 | 0.063 | 2.53 | 109–131 | 327–393 |

| 2005p | 1.76–1.82 | 0.088–0.091 | 3.52–3.64 | 83–111 | 249–333 |

| 2007p | 2.45–2.62 | 0.122–0.131 | 4.90–5.25 | 115–160 | 345–480 |

| 2009p | 3.18–3.53 | 0.159–0.176 | 6.37–7.06 | 123–181 | 369–543 |

| 2011p | 4.14–4.75 | 0.207–0.237 | 8.29–9.50 | 159–244 | 477–732 |

| 2013p | 5.01–5.96 | 0.250−0.298 | 10.03–11.92 | 145–242 | 435–726 |

| 2015p | 6.06–7.48 | 0.303−0.373 | 12.13–14.95 | 176–303 | 528–909 |

p, projected.

a Includes all foreigners, not just medical tourists.

b Years 2001–2003, data from Ministry of Commerce survey adjusted upward by 30%; years 2005 and 2007, growth rate assumed to be at 18–20% per year; years 2009 and 2011, growth rate assumed to be at 14–16% per year; years 2013 and 2015, growth rate assumed to be at 10–12% per year.

c (3) = [(1) + 20] × (2).

d Each physician assumed to be able to accept 10 000 to 12 000 foreign outpatient visits per year (40 to 48 patients per day).

e Projection revised by the author with each physician assumed to be able to see a maximum of 16 foreign patients per day. This revised projection was made by adjusting the assumption on physicians’ time spent with each patient, which would triple the demand for physicians: (5) = (4) × (3).

Source: (1) to (4) data from Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert.10

Thai patient demand for physicians

Thailand’s universal health-care coverage includes the social security scheme, the civil servant medical benefit scheme and a “gold card” scheme (known as the “30-baht scheme” before the 30-baht fee was abolished in 2006).13 The gold card scheme requires 1 general practitioner per 10 000 people at the primary-care level. This standard is low. If we assume an average of 2.5 annual visits per patient, by this standard the average general practitioner would have to see 100 outpatients daily and work 250 days per year. When these figures are combined with the optimum ratio stipulated by the Ministry of Public Health of 1.5 specialists for every general practitioner, the overall requirement would be for 1 physician per 4000 people.

If we apply the minimal human resource standard set by the gold card scheme to all schemes under the assumption that physicians are uniformly distributed throughout the country in proportion to population density, a minimum of 16 250 physicians would be needed for the 65 million Thais. However, this assumption is unrealistic. The per capita distribution of physicians is very uneven in Thailand. According to Table 2, there were 21 051 physicians in 2006. However, in the north-eastern region, which is the largest both in terms of territory and population, the number of physicians in both the public and the private sectors is still below the meagre standard of 1 physician per 4000 people.

Table 2. Number and distribution of physicians in Thailand, by year, 1996–2006.

| Year | No. of physicians |

Population per physician |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | Other government agencies | Public hospitals | Private hospitals | Total | Entire country | BKK | Central region | North-eastern region | Northern region | Southern region | ||

| 1996 | 7 733 | 5 151 | 12 884 | 3 325 | 16 209 | 3 689 | 727 | 4 598 | 9 951 | 5 811 | 5 217 | |

| 1997 | 8 026 | 5 299 | 13 325 | 3 244 | 16 569 | 3 649 | 720 | 4 506 | 9 951 | 5 791 | 5 216 | |

| 1998 | 9 636 | 4 752 | 14 388 | 3 567 | 17 955 | 3 406 | 762 | 3 614 | 8 218 | 5 050 | 4 814 | |

| 1999 | 9 799 | 4 938 | 14 737 | 3 403 | 18 140 | 3 394 | 762 | 3 654 | 8 110 | 4 869 | 4 888 | |

| 2000 | 9 363 | 4 742 | 14 105 | 3 920 | 18 025 | 3 427 | 793 | 3 576 | 8 311 | 4 501 | 5 194 | |

| 2001 | 10 068 | 4 495 | 14 563 | 4 384 | 18 947 | 3 277 | 760 | 3 375 | 7 614 | 4 488 | 5 127 | |

| 2002 | 8 821 | 5 136 | 13 957 | 3 572 | 17 529 | 3 569 | 952 | 3 566 | 7 251 | 4 499 | 4 984 | |

| 2003 | 9 321 | 4 967 | 14 288 | 3 818 | 18 106 | 3 577 | 974 | 3 417 | 7 542 | 4 754 | 4 632 | |

| 2004 | 9 375 | 5 968 | 15 343 | 3 575 | 18 918 | 3 476 | 924 | 3 301 | 7 409 | 4 766 | 4 609 | |

| 2005 | 9 928 | 5 389 | 15 317 | 4 229 | 19 546 | 3 182 | 867 | 3 054 | 7 015 | 3 768 | 4 306 | |

| 2006 | 11 311 | 5 431 | 16 742 | 4 309 | 21 051 | 2 975 | 886 | 2 963 | 5 738 | 3 351 | 3 789 | |

BKK, Bangkok; MPH, Ministry of Public Health.

Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert also projected the additional demand for physicians by Thai patients until the year 2015 (Table 3).10 Their projection, even after adjustment for foreign patients’ demand for physicians, suggests a potential improvement in the situation after 2010, when new medical graduates will expectedly increase from 1500 to 2300 per year and exceed the additional number needed (Table 4). However, there are several shortcomings to this approach. First, the authors assume that one physician can attend from 18 000 to 20 000 outpatient visits (or 900 to 1000 inpatients) per year, or as many as 72 to 80 patients per day. Second, this approach is based on the flow of new demand and supply, without considering past physician shortages. Third, the actual distribution of medical staff is very uneven in Thailand and redistribution attempts have rarely succeeded. Moreover, most foreign patient demand is for specialists averaging 10 or more years of training and practice. Therefore, surging demand for particular specialists from medical tourism could still generate shortages in particular specialty areas, despite any net surplus of new physicians.

Table 3. Projected demanda for physicians by Thai patients, Thailand, 2003–2015.

| Year | Estimated visits per patient per year |

Population (million) | Outpatient equivalent visits (million) | Demand for physicians by Thai patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatients | Inpatients | ||||

| 2001 | 2.87 | 0.066 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2002 | 2.84 | 0.076 | 62.0 | 198.65–208.07 | NA |

| 2003p | 3.62 | 0.086 | 63.3 | 247.50–258.39 | 2443–2795 |

| 2005p | 3.87 | 0.092 | 64.5 | 270.18–282.07 | 1134–1315 |

| 2007p | 4.29 | 0.099 | 65.7 | 302.10–315.15 | 1596–1838 |

| 2009p | 4.77 | 0.106 | 67.0 | 338.40–352.65 | 1815–2083 |

| 2011p | 5.16 | 0.113 | 68.2 | 371.17–386.66 | 1639–1889 |

| 2013p | 5.59 | 0.120 | 69.4 | 407.78–424.55 | 1830–2105 |

| 2015p | 6.03 | 0.127 | 70.7 | 445.59–463.70 | 1891–2175 |

NA, not applicable; p, projected.

a Under the assumptions that only 70% of outpatients need to see a physician and that each physician can attend 18 000 to 20 000 Thai outpatients (or 900 to 1000 inpatients) per year, equivalent to approximately 72 to 80 outpatient visits a day.

Source: Pachanee & Wibulpolprasert.10

Table 4. Projected total demand for physicians in Thailand, by year, 2007–2015.

| Year | Incremental demand by Thai patients (1) | Incremental demand by foreign patientsa (2) | Total incremental demand per 2 years (3)b | Total incremental demand per year (4)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007p | 1596–1838 | 345–480 | 1941–2318 | 971–1159 |

| 2009p | 1815–2083 | 369–543 | 2184–2626 | 1092−1313 |

| 2011p | 1639–1889 | 477–32 | 2116–2621 | 1058−1311 |

| 2013p | 1830–2105 | 435–726 | 2265–2831 | 1133−1416 |

| 2015p | 1891–2175 | 528–909 | 2419–3084 | 1210−1542 |

p, projected.

a Estimated by the authors assuming that each physician can see no more than 16 foreign patients per day.

b (3) = (1) + (2).

c (4) = (3) ÷ (2).

Physicians are not the only medical workers in short supply. At present, dentists are in extremely short supply, especially in rural areas, and their shortage is arguably greater than that of physicians. In 2006, Thailand had fewer than 4200 dentists; the ratio of people to dentists was 15 000:1 in the country and 22 000:1 in the north-eastern region.9 Since many medical tourists fly in for dental work, medical tourism can have a very profound effect on Thai patients’ access to dental care. The shortage of nurses is another major problem, according to several hospital administrators.

Effect on health-care service prices

In general, the price of a non-exportable good or service is determined solely by domestic demand and supply. A flux of medical tourists (in greater numbers than any increase in the number of physicians, including as a result of returning from abroad or migrating back into the country) would therefore increase the price of health-care services in Thailand.

Although higher prices for health-care services potentially generate more foreign revenue for the country, foreigners’ demand for health-care services could undermine local patients’ access to quality health care. Here we examine trends in the relative price of health-care services in various private hospitals, some catering to foreign patients and others to local patients. We collected and analysed data for 2003–2008 (or for the years for which the most recent data were available) on the total charges per patient (or for a typical patient package) for the five representative medical procedures mentioned earlier in the paper. While the average charges for these procedures increased substantially during 2006–2008 (by 10–25% per year in most hospitals in this study), between 2003–2005 most price increases were single-digit and prices even dropped in a representative hospital (e.g. averaging 1.1% per year for caesarean section, 8.8% for appendectomy, − 0.9% for hernia repair surgery and − 4.9% for knee surgery). These data are consistent with public complaints that rapidly rising medical charges in private hospitals are making it more difficult for many middle-income Thais to continue to seek treatment in high-end hospitals, on which they used to rely on a regular basis. Although data on prices alone are not sufficient to test the hypothesis that the recent rapid increase in the price of health-care services stems from the expansion of medical tourism, they are consistent with predictions based on economic theory.

While the prices of health-care services have increased, most Thais with modest incomes have now become more dependent on the universal health-care coverage scheme.14 Moreover, since hospitals for medical tourists have lured many highly skilled physicians and specialists out of public and teaching hospitals, the majority of Thais will henceforth probably receive health-care services of lesser quality (or have reduced access and shorter visiting times). To maintain the quality of the services these public schemes provide, in late 2008 the Ministry of Public Health drastically changed its compensation scheme by practically doubling physicians’ total salary in all community hospitals and by substantially increasing dentists,’ pharmacists’ and nurses’ compensation. In late 2009, the same hikes were also applied in the Ministry’s provincial and regional hospitals. Initially hospitals had to finance their pay hikes with their own savings, but after the first year the government provided additional budget to community hospitals and subsequently gave an emergency funds to remaining Ministry hospitals. Eventually, these pay hikes will substantially increase the capitation budget for the universal health-care coverage scheme, which was already more than doubled between fiscal years 2001 and 2011 (1202 versus 2546 baht per capita, respectively), even before the inclusion of the pay hike. Thus, the competing demand for health-care staff generated by medical tourism will more than likely lead the Thai government to increase its budget for public health-care services – especially to cover physicians’ incomes – at a higher and faster rate than in the absence of medical tourism.

Discussion

Medical tourism generally involves transporting patients from developed countries to developing countries where they can get treated at lower expense. These patients do not necessarily belong to the highest social bracket in their own countries, but they (and their insurers) generally have greater purchasing power than most patients in the destination countries. Most developing country governments see medical tourism as an opportunity to generate more national income and therefore support it strongly.15–17 However, without appropriate management medical tourism can become a heavy burden for the public health systems of these countries, especially those with universal health-care coverage.

In Thailand, medical tourism has both positive and negative effects. For the Thai economy, medical tourism generates a value added approximately equal to 0.4% of the GDP. It helps raise income for the medical services sector, the tourist sector and all related businesses, and it provides other intangible benefits. All of these direct and indirect positive effects for the Thai economy are well recognized in the business arena.

The negative effects for Thai society stem from having to provide health-care services for 420 000 to 500 000 medical tourists annually with the same number of health-care staff. In this study these negative effects are evidenced by both a shortage of physicians and by increased medical fees for self-paying Thais, which are likely to undermine their access to quality medical services. The very same problems are likely to apply to other host countries. In India, similar adverse effects have been detected.18,19 More importantly, the influx of medical tourists does not always lead to a “win-win situation” and to “windfall” income for host country governments, which may need to learn the hard way that they will have to increase their health budgets to meet the rising and highly competitive foreign demand for health services.

To alleviate the shortage of staff and reduce health-care costs for Thais, Thailand needs to increase its health sector human resources, especially physicians, dentists and nurses. We recommend that the government: (i) allow certified foreign physicians to provide medical services – at least to foreign patients – without having to take a medical certification exam in the Thai language, as currently required; (ii) increase medical staff training in public universities to full capacity; and (iii) collaborate with private hospitals in training more specialists.

Medical education in Thailand is neither self-funded nor privately funded; rather, it is heavily subsidized by Thai taxpayers. With their much higher purchasing power, medical tourists can prevent Thai taxpayers from accessing quality health care. Thus, the Thai government has a responsibility to balance the welfare of Thai citizens against the extra income generated by medical tourism. The government has strong grounds for levying a tax on medical tourists, who, unlike Thai taxpayers and expatriates residing in Thailand, reap benefits without helping to pay the taxes that support physician training. The revenue from this tax should be used to expand the training of physicians and other medical staff and to retain the best professors in public medical schools. In the short run, the taxes could also mitigate the adverse effects of the extra demand for health-care services on the part of foreigners with higher purchasing power.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sirachai Jindarak (researcher), Ammar Siamwalla, Panlada Tripittayakul and Nontalee Vuttimanop, as well as the participants at the International Academy of Business and Public Administration Disciplines (IABPAD) Conference in Dallas, Texas, April 23–26, 2009.

Funding:

This article is grounded in a research project funded by the Office of the National Economic and Social Advisory Council of Thailand. The research won the 2009 Good Research Award in Political Sciences and Public Administration from Thailand’s National Research Council.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Asian medical tourism analysis (2008–2012) New Delhi: RNCOS Industry Research Solutions; 2009. Available from: http://www.rncos.com/Market-Analysis-Reports/Asian-Medical-Tourism-Analysis-2008-2012-IM105.htm [accessed 18 February 2011].

- 2.Ministry of Public Health. Strategies to develop Thailand as a centre of excellent health care of Asia. Nonthaburi: MPH; 2003.

- 3.Healthcare Services Working Group. Developing Singapore as the compelling hub for healthcare service in Asia Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry; 2002. Available from: https://app.mti.gov.sg/data/pages/507/doc/ERC_SVS_HEA_Annex1.pdf [accessed 18 February 2011].

- 4.Overview of medical tourism – give back deck Boston Consulting Group; 2008.

- 5.NaRanong A, NaRanong V, Jindarak S. The development guideline for Thailand’s medical hub Bangkok: National Institute of Development Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tisayaticom K, Patcharanarumol W, Tangcharoensathien V. Unit cost analysis: standard and quick methods. J Health Sci. 2001;10:359–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalie C. Costs of health care services of public hospital: the case study of four hospitals in Bangkok [thesis]. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NaRanong V, NaRanong A. The flow of health personnel in public hospitals (Research Report No. 5). Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute; 2005.

- 9.Ministry of Public Health. Monitoring and management system (MMS) [Internet]. Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public Health; 2006. Thai. Available from: http://moc.moph.go.th/Resource/Personal/index,new.php [accessed 18 February 2011].

- 10.Pachanee CA, Wibulpolprasert S. Incoherent policies on universal coverage of health insurance and promotion of international trade in health services in Thailand. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:310–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thammarangsri T. The appropriate geographical distribution of doctors under the universal health care coverage schemes. Bangkok: Health Insurance System Research Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pananiramai M, Sooksirisereekul S. Projection of illness patterns and demand for doctors. Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NaRanong V, NaRanong A, Triamworakul S, Wongmonta S. Universal health coverage schemes in Thailand 2002–2003 (revised March 2005). Bangkok: Thailand Development Research Institute; 2005.

- 14.NaRanong A. The 30 baht health care scheme and health security in Thailand Bangkok: National Institute of Development Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thukral P. Indian government all set to boost medical tourism. Thaindian News 2009 Feb 14. Available from: http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/press-release/indian-government-all-set-to-boost-medical-tourism_100153734.html [accessed 23 February 2011].

- 16.Leng CH. Medical tourism in Malaysia: international movement of healthcare consumers and the commodification of healthcare (Working Paper Series No. 83) Singapore: Asia Research Institute; 2007. Available from: http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/showfile.asp?pubid=642&type=2 [accessed 18 February 2011].

- 17.Singapore’s Tourism Board. Singapore set to be healthcare services hub of Asia [press release]. 2003 Oct 20. Available from: http://www.singaporemedicine.com/pr/new0201c.asp?id=881 [accessed 23 February 2011].

- 18.Hazarika I. The potential effect of medical tourism on health workforce and health systems in India Asia Pacific Action Alliance on Human Resources for Health; 2008. Available from: http://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/2281 [accessed 23 February 2011].

- 19.Ramírez de Arellano AB. Patients without borders: the emergence of medical tourism. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37:93–8. doi: 10.2190/4857-468G-2325-47UU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]