Abstract

Problem

Birth and death registration rates are low in most parts of India. Poor registration rates are due to constraints in both the government system (supply-side) and the general population (demand-side).

Approach

We strengthened vital event registration at the local level within the existing legal framework by: (i) involving a non-profit organization as an interface between the government and the community; (ii) conducting supply-side interventions such as sensitization workshops for government officials, training for hospital staff and building data-sharing partnerships between stakeholders; (iii) monitoring for vital events by active surveillance through lay-informants; and (iv) conducting demand-side interventions such as publicity campaigns, education of families and assistance with registration.

Local setting

In the government sector, registration is given low priority and there is an attitude of blaming the victim, ascribing low levels of vital event registration to “cultural reasons/ignorance “. In the community, low registration was due to lack of awareness about the importance of and procedures for registration.

Relevant changes

This initiative helped improve registration of births and deaths at the subdistrict level. Vital event registration was significantly associated with local equity stratifiers such as gender, socioeconomic status and geography.

Lessons learnt

The voluntary sector can interface effectively between the government and the community to strengthen vital registration. With political support from the government, outreach activities can dramatically improve vital event registration rates, especially in disadvantaged populations. The potential relevance of the data and the data collection process to stakeholders at the local level is a critical factor for success.

ملخص

المشكلة

مازالت معدلات تسجيل الولادات والوفيات منخفضة في أغلب مناطق الهند. ويرجع سوء معدلات التسجيل إلى قصور في كل من النظام الحكومي (الطرف المُقدِّم للخدمة) وعامة السكان (الطرف الطالب للخدمة).

الأسلوب

قمنا بتعزيز تسجيل الإحصائيات الحيوية ضمن الإطار القانوني الموجود عن طريق: 1) إشراك المنظمات غير الربحية كوسيط بين الحكومة والمجتمع؛ 2) إجراء تدخلات عل صعيد الطرف المُقدِّم للخدمة مثل حلقات العمل لاستثارة المسؤولين الحكوميين، وتدريب العاملين في المستشفيات، وبناء شراكات لتبادل المعطيات بين الجهات المعنيّة؛ 3) مراقبة الأحداث الحيوية عن طريق ترصٍّد نشطٍ يقوم به مقدمو معلومات من الأفراد العاديين؛ 4) إجراء تدخلات على صعيد الطرف الطالب للخدمة مثل الحملات الدعائية، وتثقيف الأسر ومساعدتهم في التسجيل.

المواقع المحلية

في قطاع الحكومة، تُعطَى أولويةٌ متدنية للتسجيل، وهناك موقف ثابت في إلقاء اللوم على الضحية، فيُعزَى الأمر في تدني مستويات تسجيل الإحصائيات الحيوية إلى "الأسباب الثقافية/والجهل". وبالنسبة للمجتمع، فإن تدني التسجيل يرجع إلى نقص الوعي حول أهمية وإجراءات التسجيل.

التغيّرات ذات الصلة

ساعدت هذه المبادرة على تحسين تسجيل الولادات والوفيات في المستويات الأقل من المقاطعات. ارتبط تسجيل الإحصائيات الحيوية ارتباطاً وثيقاً بطبقات العدالة المحلية مثل الجنس، والحالة الاقتصادية والاجتماعية، والمناطق الجغرافية.

الدروس المستفادة

يمكن للقطاع التطوّعي أن يتوسط بفعاليّة بين الحكومة والمجتمع من أجل تعزيز تسجيل الإحصائيات الحيوية. ويمكن للأنشطة الإيصالية، بدعم سياسي من الحكومة، أن تحسّن على نحو كبير معدلات تسجيل الإحصائيات الحيوية، ولاسيما في المجتمعات المهمّشة. وتُعد الأهمية المتوقّعة للمعطيات وعملية جمع المعطيات بالنسبة للجهات المعنيّة على المستوى المحلي عاملاً هاماً للنجاح.

Résumé

Problème

Les taux d’enregistrement des naissances et des décès sont faibles dans la plupart des régions d’Inde. Ces taux si bas sont dus aux contraintes du système public (côté offre) et de la population générale (côté demande).

Approche

Dans le cadre juridique existant, nous avons renforcé l’enregistrement des événements relatifs à l’état civil au niveau local comme suit: (i) en impliquant une organisation à but non lucratif comme interface entre le gouvernement et la communauté; (ii) en effectuant des interventions côté offre, telles que des ateliers de sensibilisation pour les fonctionnaires d’État, la formation du personnel hospitalier et la création de partenariats de partage des données entre les parties prenantes; (iii) en contrôlant les événements relatifs à l’état civil par la surveillance active via des informateurs non spécialistes; et (iv) en effectuant des interventions côté demande, telles que des campagnes publicitaires, l’éducation des familles et l’assistance à l’enregistrement.

Environnement locale

Dans le secteur public, on donne une faible priorité à l’enregistrement des événements relatifs à l’état civil et on constate une attitude qui consiste à blâmer la victime, en attribuant ces niveaux faibles d’enregistrement à «l’ignorance/des raisons culturelles». Au sein de la communauté, ce faible taux d’enregistrement était dû à un manque de sensibilisation quant à l’importance de l’enregistrement et de ses procédures.

Changements significatifs

Cette initiative a permis d’améliorer l’enregistrement des naissances et des décès au niveau du sous-district. L’enregistrement des événements relatifs à l’état civil était largement associé aux facteurs de stratification de l’équité locale, comme le sexe, le statut socioéconomique et la géographie.

Leçons tirées

Le secteur associatif peut efficacement être le point de contact entre le gouvernement et la communauté afin de renforcer l’enregistrement des événements relatifs à l’état civil. Avec le soutien politique des autorités, les activités sociales sur le terrain peuvent considérablement améliorer les taux d’enregistrement des naissances et des décès, en particulier chez les populations défavorisées. La pertinence potentielle des données et le processus de collecte des données des parties prenantes au niveau local est un facteur de succès fondamental.

Resumen

Situacíon

La mayor parte de la India presenta unos índices bajos de registros de nacimientos y defunciones. Estos bajos índices de registro se deben a las limitaciones existentes, tanto en el sistema gubernamental (suministro) como en la población en general (demanda).

Enfoque

Hemos consolidado las inscripciones del registro civil a nivel local dentro del marco legal existente, aplicando los siguientes métodos: (a) implicación de una organización sin ánimo de lucro para actuar como intermediaria entre el Gobierno y la comunidad; (b) intervenciones dirigidas al sistema público, como talleres de sensibilización destinados a los funcionarios públicos, formación del personal hospitalario y creación de asociaciones entre los interesados para compartir información al respecto; (c) supervisión de las inscripciones en el registro civil mediante un control activo a través de informadores no especializados; y (d) intervenciones dirigidas a la población en general como campañas de publicidad, formación de las familias y ayuda en el registro.

Marco regional

El sector gubernamental asigna un nivel bajo de prioridad al registro y suele culpar a la víctima, atribuyendo el bajo porcentaje de inscripciones a «motivos culturales e ignorancia». En la comunidad, el bajo porcentaje se debió a una falta de concienciación sobre la importancia del registro y sus procedimientos.

Cambios importantes

Esta iniciativa ayudó a mejorar la inscripción de nacimientos y defunciones en los subdistritos. La inscripción en el registro civil se asoció de manera significativa a estratificadores locales de equidad como el género, el nivel socioeconómico y la geografía.

Lecciones aprendidas

El voluntariado puede intermediar de forma efectiva entre el Gobierno y la comunidad para consolidar el registro civil. Con el apoyo político del Gobierno, las actividades de divulgación pueden mejorar enormemente los índices de inscripciones en el registro civil, especialmente entre las poblaciones menos favorecidas. La importancia potencial de los datos y del proceso de recopilación de datos para los interesados a nivel local es un factor fundamental de éxito.

Резюме

Проблема

В большинстве районов Индии показатели регистрации рождений и смертей низкие. Неудовлетворительные показатели регистрации актов гражданского состояния объясняются ограничениями как со стороны государственной системы (т. е. спроса), так и со стороны населения (т. е. предложения).

Подход

Нам удалось улучшить регистрацию актов гражданского состояния на местном уровне в рамках существующих правовых норм путем: (1) привлечения некоммерческой организации в качестве посредника между государством и местной общиной; (2) проведения мероприятий «со стороны предложения», таких как семинары по повышению чувствительности для государственных чиновников, обучение персонала больниц и формирование партнерств по обмену данными между заинтересованными сторонами; (3) мониторинга актов гражданского состояния путем их активного отслеживания непрофессиональными наблюдателями; и (4) проведение мероприятий «со стороны спроса», таких как информационно-пропагандистские кампании, просвещение членов семей и содействие в проведении регистрации.

Местные условия

В государственном секторе не придается большого значения регистрации актов гражданского состояния и распространена привычка возлагать вину на пострадавшего. Низкий уровень регистрации приписывается «особенностям менталитета» и «невежеству». На уровне местной общины причиной низкого уровня регистрации было отсутствие информированности о значении процедур регистрации.

Осуществленные перемены

Данная инициатива помогла улучшить регистрацию рождений и смертей на муниципальном уровне. Регистрация актов гражданского состояния в значительной степени коррелировала с местными факторами стратификации, такими как гендерная принадлежность, социально-экономический статус и географическое местоположение.

Выводы

Добровольный сектор может эффективно выступать в качестве посредника между государством и местной общиной, способствуя улучшению регистрации актов гражданского состояния. При политической поддержке государства информационно-пропагандистские мероприятия могут содействовать резкому повышению показателей регистрации актов гражданского состояния, особенно среди популяций, находящихся в уязвимом положении. Важнейшим фактором успеха является потенциальная значимость данных и процесса их сбора для заинтересованных сторон на местном уровне.

摘要

问题

印度大部分地区的出生和死亡登记率都很低。低登记率归因于政府系统(供给方)和公众(需求方)两个方面的限制。

方法

我们在现行法律框架的范围内通过下述方法加强了地方生命事项登记:(i)相关非盈利组织作为政府和社区之间的接口;(ii)进行供给方干预,如针对政府官员的意识强化研讨会、医务人员培训以及建立利益相关者之间的数据共享合作关系;(iii)通过非专业知情人对生命事项进行积极监测;(iv)进行需求方干预,如宣传活动、家庭教育和登记援助。

当地状况

政府部门中,生命登记没有给予优先关注,因为普遍认为受害人应该受到指责并将生命事项登记水平低归结为“文化原因/无知”。而在社区中,登记率低是由于缺乏对登记重要性和登记手续的认识。

相关变化

这一举措帮助改善了街道一级的出生和死亡登记。有关生命事项的登记与当地权益阶层因素如性别、社会经济地位和地理位置呈显著相关。

经验教训

志愿部门可以担当政府和社区之间的有效接口从而加强生命事项登记。有了政府的政策支持,宣传工作能够显著提高生命事项的登记率,特别是在弱势群体中。地方一级数据和数据收集过程与利益相关者之间的潜在关联是成功的关键因素。

Introduction

Reliable vital statistics based on births and deaths are necessary for population health assessment, epidemiological research, health planning and programme evaluation. Civil registration is considered the optimal source of statistics on vital events (i.e. births and deaths). The national authority for civil registration in India is the Office of the Registrar-General and Census Commissioner, under the Ministry of Home Affairs. Registration is, however, decentralized to India’s 29 states and 6 union territories. In theory, India’s registration system provides a good basis for overall coordination, direction, technical guidance and standards for birth and death statistics, but the reality is vastly different. For the period 2000–2006, birth registration in India was 41% and death registration was < 25%,1 with large regional differences. In Andhra Pradesh state, birth registration was 50% and death registration was 25%.2,3 Numerous factors including political, administrative, economic and legislative barriers, and neglect of cultural and community realities act as constraints to the complete, accurate and timely registration of births and deaths in India.3,4 This paper describes an initiative called Strengthening of Local Vital Event Registration (SOLVER) by a nongovernmental organization that worked with the government and the public at a subdistrict level in southern India.

Programme setting

The programme was held in five mandals (subdistricts) – Palamaner, Gangavaram, Baireddypalle, V Kota and Ramakuppam – with a total population of 281 500 (in the year 2007) in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh state. The first three proximal mandals were located at a mean distance of 15 km and the last two distal mandals were at a mean distance of 50 km away from Palamaner, the main town. Estimated annual number of births and deaths were 5320 and 2055 respectively, based on crude birth and death rates of 18.9 and 7.3 per 1000 respectively.5

System components

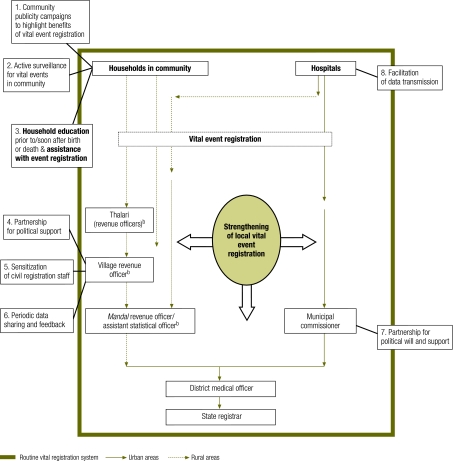

The duration of the programme was 12 months (September 2007–August 2008). Fig. 1 summarizes the existing process of vital event registration, the various interventions3,4 and the consequent learning points for improving civil registration in India.6,7 These interventions targeted both the “supply-side” (civil registration and vital statistics by the government) and the “demand-side” (service utilization by the community) with the objective of achieving target rates of 75% for birth registration and 50% for death registration.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework of systems approach to strengthening of different elements of vital event registration in Andhra Pradesh state, India, 2007–08a

Mandal, sub-district administrative region with population of approximately 50 000.

a Interventions to improve registration are shown outside the outline box in anti-clockwise direction. Household-level interventions (in boxes 1, 2 and 3), government-related interventions (in boxes 4, 5, 6 and 7) and hospital-level interventions (in box 8).

b Thalari and village revenue officers are personnel in charge of registration at village-level; Mandal revenue officers and assistant statistical officers are personnel in charge at mandal-level.

Supply-side interventions

The nongovernmental organization (St John’s Research Institute, Bangalore, India) fostered partnerships with local government departments including revenue, social welfare, health and education.8

Awareness workshops on registration procedures were held at each mandal, chaired by the mandal revenue officer/assistant statistical officer.

Data management mechanisms were set up between the government and project staff to share information on vital events in the project area. Discussions were held with public and private hospitals for transmission of data on births and deaths to the government. Procedures were also established to evaluate project outcomes using evidence of birth and death registration.

Demand-side interventions

Publicity campaigns were conducted to improve awareness in the community using various media such as pamphlets, audio announcements via village drummer and recorded messages, and brief jingles on local cable television.

The project staff visited households to inform them of the juridical and statistical benefits of vital event registration.9 Juridical benefits include establishing nationality, legal rights, ration card/identity card/passport, access to education, welfare schemes and utility services. Registration also has the statistical purpose of enabling measurement and monitoring of the health status of the population.

This education was subsequently followed by encouragement for registration. Overall, 78% (3322/4259) of families were encouraged successfully to proceed with birth registration. It was significantly higher in rural (80%) than urban areas (70%) (P < 0.005) and in proximal (82%) than distal mandals (74%) (P < 0.005); it did not vary by sex of baby (P = 0.68) or place of delivery (institutional vs home) (P = 0.51). Encouragement for death registration was successfully carried out in 63% (857/1361) of households. It was significantly higher in urban (70%) than rural areas (61%) (P = 0.01); it did not vary by sex of deceased (P = 0.78), age at death (P = 0.53), place of death (P = 0.83) or location of mandals (P = 0.46). Key reasons for lack of success were non-availability of families due to migration or conflicting work schedules in urban areas and women relocating to their mothers’ houses to give birth.

The identification of vital events was done by about 400 local lay-informants who were paid a small honorarium for reporting to project staff within 2–3 days of the event. Households were advised on how and where to register within 14 days after births and within 7 days after deaths (Fig. 1).

Lessons learnt

Processes

Awareness work with managerial staff from local government departments was important because of their involvement in various registration activities. However, there was a lack of clarity on their roles and responsibilities. While the state authorizes the village revenue officer to issue certificates, these were often issued only at the mandal level, necessitating unnecessary travel to collect certificates. These workshops helped to partially decentralize registration to the village level.

In advocacy meetings, there was low participation of private medical practitioners and very few medical officers or health officials among the health workers from the government sector. Separate advocacy meetings with private clinics resulted in increased birth registration, less so with death registration.

Active surveillance by lay-informants yielded a large number of events that would not have been picked up by the short-staffed government system. Death registration levels were especially low at extremes of age (i.e. among children and the elderly). Although certificates were supposed to be free, some households reported incurring expenses either because of multiple visits or because of unofficial payments to collect the certificate.

A lack of computerization/training was an impediment to efficient dataflow and feedback. The involvement of personnel from different departments led to “blame-shifting “. Furthermore, due to the lack of a unique identification system in India, there was also the possibility of duplicate registration of events, especially among women giving birth at their mothers’ homes.

Outputs

During the programme, 80% of births and 61% of deaths were registered, as compared with pre-intervention rates of 50% of births and 25% of deaths.3 While birth registration rose from 50% to over 80% in about 4 months after the start of the programme, death registration reached a peak 3 months later. Registration rates for both births and deaths were higher in households that received the intervention; these differences were statistically significant for all determinants (P < 0.01). Registration of births was significantly associated with residence (urban > rural; P < 0.01), place of delivery (institutional > home; P < 0.001) and location of mandal (proximal > distal; P < 0.01); it did not vary by sex of baby (P > 0.05). Further, encouragement and guidance for registration tended to narrow the male–female gap, urban–rural gap and the proximal–distal mandal gap. Similarly, registration of deaths was associated with sex (males > females; P < 0.01), age (middle-age > extremes of age; P < 0.01), residence (urban > rural; P < 0.01) and location of mandal (proximal > distal; P < 0.01); it did not vary by place of death (P > 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis yielded similar results.

Discussion

Vital statistics are inextricably linked to health and development outcomes;10 and the social advantage linked to vital event registration could vary by key equity stratifiers – socioeconomic status, gender and geography.10,11 Before the intervention, gender was linked to both birth and death registration. Place of delivery is a proxy for socioeconomic status given that < 10% of Indians have access to health insurance.12 Geographic considerations such as urban/rural residence and location of the subdistrict could affect event registration either as a logistic issue (by way of distance, topography or transport difficulties) or as a political issue (by way of resource allocation or discrimination).11

In addition to the supply-side interventions, the unique outreach strategy of combining education/guidance of the public with active surveillance increased birth registration substantially and death registration modestly in this rural area. Though assessing cost-effectiveness of this initiative was not a specific objective, crude estimates of costs incurred totalled about 2 Indian rupees (US$ 0.05) per person which is considered cost-effective for a vital events surveillance system by the Disease Control Priorities Project for developing countries.13 Note these costs were in addition to the existing vital registration system.

Key lessons learnt should enable targeted interventions that are sustainable and cost-effective. For example, community campaigns, strengthening collaboration between government departments, capacity building of health staff, holding intensive mobile registration drives to target priority areas such as rural home deliveries and deaths of children and elderly people.

Corruption in the issue of certificates was a recurrent problem. Though it might have reduced to some extent by a more efficient registration system during the intervention period, it was still reported by citizens. A new mother-and-child tracking system was expected to reduce problems due to migration, duplication and others.

Key limitations of the programme included difficulty determining the contribution each intervention made towards improving registration, as well as uncertainty about sustaining registration at high levels in the long-term. Further, it is possible that those who did not receive the household intervention were a biased group whose unmeasured characteristics were likely to be confounded with their choices to register. Lastly, the focus and intensity of the intervention itself could have caused favourable outcomes (Hawthorne effect or observation bias).

The Commission on the Social Determinants of Health has identified that further strengthening is needed on the evidence base on the social determinants of health and what works to improve them.10 This initiative aims, in part, to fulfil a gap in understanding vital registration through identification of problems and provision of solutions with consequent improvements in birth/death registration as evidence. Identifying variations in event registration by local equity stratifiers could help improve the targeting of services. Civil society plays an important role in supporting public participation, providing feedback on which to base improvements to the system, and intervention efforts for increasing registration. It could also help increase accountability within the civil registration system.14,15

In summary, coordinated efforts at the local level by voluntary organizations, government and the general public can improve birth and death registration in developing countries. Lessons learnt at the local level can then be used to identify scalable solutions at a regional or national level (Box 1).

Box 1. Summary of main lessons learnt.

Voluntary organizations can facilitate government–society interaction and help increase local vital event registration.

Multi-level interventions – at the community, government and household-level – were effective.

Equity stratifiers such as gender, socioeconomic status and geography affect vital event registration rates in communities; there may be a need to target services to those who need it the most.

Funding:

This study received partial financial support from the Sir Ratan Tata Trust, Mumbai, India.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.World health statistics 2008 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2008/en/index.html [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 2.States classified by levels of registration, annex 9.2. New Delhi; Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner; 2005. Available from: http://mospi.nic.in/nscr/ax0902.htm [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 3.George A, Jaymon KC. Constraints in birth registration: case study in Andhra Pradesh. Mumbai: eSocialSciences portal; 2005. Available from: http://www.esocialsciences.com/Articles/displayArticles.asp?Article_ID=279 [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 4.Serrao A, Sujatha BR. Birth registration: a background note Bangalore: Community Development Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sample Registration System (SRS) Bulletin, vol 42. no 1. New Delhi: Registrar General of India; 2007. Available from: http://censusindia.gov.in/Vital_Statistics/SRS_Bulletins/SRS_Bulletins_links/SRS_Bulletin_-_October_2007-1.pdf [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 6.Recommendations for improving birth registration, document ID 216. Surrey: Plan International; 2009. Available from: http://ssl.brookes.ac.uk/ubr/files/1/27-UCP_Report_Recommendations.pdf [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 7.Count every child: ensuring universal birth registration in India New Delhi: Plan India; 2009. Available from: http://plan-international.org/birthregistration/count-every-child-in-india [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 8.National consultation for promoting government – civil society partnerships to achieve universal birth registration. New Delhi: Plan India; 2007. Available from: http://ssl.brookes.ac.uk/ubr/files/5/31_-_India-Report-Promoting_government-civil_society_partnerships_for_UBR.pdf [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 9.Jewkes R, Wood K. Competing discourses of vital registration and personhood: perspectives from rural South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1043–56. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)10036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nolen LB, Braveman P, Dachs JNW, Delgado I, Gakidou E, Moser K, et al. Strengthening health information systems to address health equity challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:597–603. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health insurance in India: current scenario. In: Regional overview in south-east Asia. New Delhi: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2003. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/linkfiles/social_health_insurance_an2.pdf [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 13.Stansfield SK, Walsh J, Prata N, Evans T. Information to improve decision making for health. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB et al. Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd edition) New York: Oxford University Press; 2006: 1017-30. Available from: http://www.dcp2.org/pubs/DCP/54/Table/54.2 [accessed 21 February 2011].

- 14.Bambas L. Integrating equity into health information systems: a human rights approach to health and information. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao C, Osterberger B, Anh TD, MacDonald M, Kim Chuc NT, Hill PS. Compiling mortality statistics from civil registration systems in Viet Nam: the long road ahead. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:58–65. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.061630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]