Abstract

Objective

To compare medical abortion practised at home and in clinics in terms of effectiveness, safety and acceptability.

Methods

A systematic search for randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies comparing home-based and clinic-based medical abortion was conducted. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, MEDLINE and Popline were searched. Failure to abort completely, side-effects and acceptability were the main outcomes of interest. Odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Estimates were pooled using a random-effects model.

Findings

Nine studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 4522 participants). All were prospective cohort studies that used mifepristone and misoprostol to induce abortion. Complete abortion was achieved by 86–97% of the women who underwent home-based abortion (n = 3478) and by 80–99% of those who underwent clinic-based abortion (n = 1044). Pooled analyses from all studies revealed no difference in complete abortion rates between groups (odds ratio = 0.8; 95% CI: 0.5–1.5). Serious complications from abortion were rare. Pain and vomiting lasted 0.3 days longer among women who took misoprostol at home rather than in clinic. Women who chose home-based medical abortion were more likely to be satisfied, to choose the method again and to recommend it to a friend than women who opted for medical abortion in a clinic.

Conclusion

Home-based abortion is safe under the conditions in place in the included studies. Prospective cohort studies have shown no differences in effectiveness or acceptability between home-based and clinic-based medical abortion across countries.

ملخص

الغرض

مقارنة ممارسات الإجهاض في المنزل والعيادة من حيث الفعاليّة، والسلامة، والمقبولية.

الطريقة

أجري بحث منهجي للتجارب العشوائية ذات الشواهد والدراسات الأترابية الاستباقية للمقارنة بين الإجهاض الطبي الذي يمارس في المنزل والعيادة. وأجري البحث في سجلات كوكران Cochrane المركزية للتجارب ذات الشواهد، وقواعد المعطيات الطبية EMBASE، وخط استرجاع النشريات الطبية MEDLINE، وقواعد معطيات المعلومات السكانية على الإنترنت Popline. وكانت مخرجات البحث محط الانتباه هي فشل الإجهاض التام، والآثار الجانبية، والمقبولية. وحُسِبَت نسب الأرجحية وفواصل الثقة 95%. وجُمِعَت التقديرات باستخدام نموذج التأثيرات-العشوائية.

النتائج

كان هناك تسع دراسات تتوافق مع معايير الإدراج في الدراسة (عدد المشاركين فيها= 4522 مشاركاً). كانت جميع الدراسات أترابية استباقية واستخدمت ميفيبريستون وميزوبروستول لإحداث الإجهاض. وقد تحقق إجهاض تام في 86% إلى 97% من النساء اللاتي أجرين الإجهاض في المنزل (عددهن= 3478)، وفي 80% إلى 99% في النساء اللاتي أجرين الإجهاض في العيادات (عددهن= 1044). وأظهرت جميع التحاليل المُجَمَّعَة للدراسات عدم وجود اختلاف في معدلات الإجهاض التام بين المجموعتين (نسبة الأرجحية= 0.8؛ فاصلة الثقة 95%: 0.5-1.5). وكان من النادر حدوث مضاعفات خطيرة مع الإجهاض. أما الألم والقيء فاستمر لمدة أطول بمقدار 0.3 يوم بين النساء اللاتي أخذن ميزوبروستول في المنزل مقارنة باللاتي أخذنه في العيادة. وكان شعور النساء اللاتي اخترن الإجهاض الطبي في المنزل على الأرجح أكثر رضاء، كما اخترن طريقة الإجهاض مرة أخرى، وأوصين بها للصديقات وذلك مقارنة بمن اخترن الإجهاض الطبي في العيادة.

الاستنتاج

كان الإجهاض المنزلي مأموناً في ظل ظروف الدراسات المُدرَجَة في البحث. وقد أظهرت الدراسات الأترابية الاستباقية عدم وجود اختلافات بين الفعاليّة أو المقبولية بين الإجهاض الطبي في المنزل أو في العيادات عبر البلدان.

Résumé

Objectif

Comparer l’avortement médical pratiqué à domicile et en clinique en termes d’efficacité, de sécurité et d’acceptabilité.

Méthodes

Une recherche systématique en essais contrôlés randomisés et en études prospectives de cohortes a été effectuée, comparant l’avortement médical à domicile et en clinique. Les recherches ont été réalisées dans le registre central Cochrane des essais contrôlés, dans EMBASE, MEDLINE et Popline. Les principaux résultats d’intérêt étaient l’échec d’un avortement complet, les effets indésirables et l’acceptabilité. Les rapports des cotes et leurs intervalles de confiance de 95% (IC) ont été calculés. Les estimations ont été regroupées à l’aide d’un modèle à effets aléatoires.

Résultats

Neuf études ont répondu aux critères d’inclusion (n = 4 522 participants). Il s’agissait entièrement d’études prospectives de cohortes ayant utilisé la mifépristone et le misoprostol pour provoquer l’avortement. Un avortement complet a été obtenu par 86 à 97% des femmes qui ont subi l’interruption de grossesse à domicile (n = 3 478) et par 80 à 99% des femmes qui ont subi l’interruption de grossesse en clinique (n = 1 044). Les analyses regroupées de l’ensemble des études n’ont révélé aucune différence dans les taux d’avortement complet entre les groupes (rapport des cotes = 0,8; 95% IC: 0,5–1,5). Rares ont été les complications graves de l’avortement. Les douleurs et les nausées ont duré 0,3 jour de plus chez les femmes qui ont pris le misoprostol à domicile plutôt qu’en clinique. Celles qui ont choisi un avortement à domicile étaient plus enclines à être satisfaites, à choisir à nouveau cette méthode et à la recommander à une amie par rapport aux femmes qui ont opté pour l’avortement médical en clinique.

Conclusion

L’avortement médical à domicile est sans danger s’il est effectué dans le respect des conditions établies dans les études examinées. Les études prospectives de cohortes n’ont montré aucune différence dans l’efficacité ou l’acceptabilité entre l’avortement médical à domicile et en clinique dans les différents pays.

Resumen

Objetivo

Comparar la efectividad, la seguridad y la aceptación de los abortos médicos practicados en el domicilio con aquellos realizados en la clínica.

Métodos

Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de ensayos clínicos controlados aleatorizados y de estudios de cohortes prospectivos, comparando los abortos médicos realizados en el domicilio y en la clínica. Se realizaron búsquedas en el Registro Central de Cochrane de Ensayos Controlados, EMBASE, MEDLINE y Popline. Los resultados de interés principales fueron el fracaso para abortar completamente, los efectos secundarios y la aceptabilidad. Se calcularon las tasas de probabilidad y sus intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95%. Se reunieron los cálculos aproximados utilizando un modelo de efectos aleatorios.

Resultados

Nueve estudios cumplieron los criterios de inclusión (n = 4522 participantes). Todos fueron estudios de cohortes prospectivos que utilizaron mifepristona y misoprostol para inducir al aborto. El aborto completo se consiguió en el 86- 97% de las mujeres que se sometieron a un aborto en el domicilio (n = 3478) y entre el 80% y el 99% de aquellas mujeres que se sometieron a un aborto en una clínica (n = 1044). Los análisis agrupados de todos los estudios no mostraron diferencias en las tasas de aborto completo entre los grupos (tasa de probabilidad = 0,8; IC del 95%: 0,5–1,5). Las complicaciones graves del aborto fueron poco frecuentes. El dolor y los vómitos duraron 0,3 días más en aquellas mujeres a las que se les administró misoprostol en el domicilio, en comparación con las que recibieron el tratamiento en la clínica. Las mujeres que optaron por un aborto médico en el domicilio mostraron un mayor grado de satisfacción, que las llevaría a elegir el método de nuevo y recomendárselo a una amiga, que aquellas mujeres que abortaron en la clínica.

Conclusión

El aborto en el domicilio es seguro siempre que el lugar cuente con las condiciones incluidas en los estudios. Los estudios de cohortes prospectivos por país no han mostrado diferencias en cuanto a efectividad o aceptabilidad entre abortos médicos en el domicilio y en la clínica.

Резюме

Цель

Сравнить медикаментозные аборты, проведенные в домашних условиях и в гинекологической клинике, с точки зрения эффективности, безопасности и приемлемости.

Методы

Проведен систематический поиск рандомизированных контролируемых испытаний и проспективных когортных исследований, в которых сравнивались медикаментозные аборты, проводившиеся в домашних условиях и с гинекологической клинике. Поиск проводился по Центральному Кокрановскому регистру контролируемых испытаний и базам данных EMBASE, MEDLINE и Popline. Основными исходами, представляющими интерес, были: неудачный аборт, побочные эффекты и приемлемость. Производился расчет отношения шансов и их 95% доверительных интервалов (ДИ). Оценки объединялись с использованием модели со случайными эффектами.

Результаты

Критериям включения соответствовали девять исследований (n = 4522 участников). Все они являлись проспективными когортными исследованиями, в которых, чтобы вызвать абортивный эффект, применялись мифепристон и мизопростол. Полный аборт был достигнут у 86–97% женщин, перенесших аборт в домашних условиях (n = 3478), и у 80–99% женщин, перенесших аборт в гинекологической клинике (n = 1044). Объединенный анализ данных всех исследований не выявил различий в показателях полного аборта между группами (отношение шансов = 0,8; 95% ДИ: 0,5–1,5). Серьезные осложнения после аборта были редкими. У женщин, принимавших мизопростол дома, а не в гинекологической клинике, боли и рвота длились на 0,3 дня дольше. Вероятность того, что женщины будут удовлетворены, вновь выберут этот метод и рекомендуют его подруге, была выше для женщин, выбравших проведение медикаментозного аборта в домашних условиях, чем для женщин, выбравших проведения медикаментозного аборта в гинекологической клинике.

Вывод

Проведение аборта в домашних условиях является безопасным, если местные условия соответствуют тем, что описаны в отобранных исследованиях. Проспективные когортные исследования не выявили различий между странами в эффективности или приемлемости медикаментозных абортов, проводившихся в домашних условиях и в гинекологической клинике.

摘要

目的

旨在比较在家或在诊所进行药物流产的有效性、安全性和可接受性。

方法

对比较在家里或在诊所进行药物流产的随机对照试验和前瞻性群组研究进行系统搜索。我们搜索了Cochrane对照试验登记处、荷兰医学文摘数据库(EMBASE)、联机医学文献分析和检索系统(MEDLINE)和人口信息数据库(Popline)。不完全流产、副作用和可接受性是我们关心的主要结果。OR值和95%置信区间(CIs)也进行计算。运用随机效应模型汇集估算结果。

结果

九项研究满足入选标准(参与者 n = 4522)。此九项研究均为运用米非司酮和米索前列醇诱导药物流产的前瞻性群组研究。在家中进行药物流产的妇女(n = 3478)实现完全流产的比例为86%到97%,而在诊所进行药物流产的妇女(n = 1044)的这一比例为80%到99%。所有研究的汇总分析显示两组(OR=0.8;95%置信区间CI:0.5-1.5)之间的完全流产率并无差异。因流产而产生的严重并发症鲜有发生。在家而非在诊所服用米索前列醇的女性,疼痛和呕吐多持续0.3天。与那些选择在诊所进行药物流产的女性相比,选择在家进行药物流产的女性更可能得到满足、再次选择此方法并将其推荐给朋友。

结论

在所纳入的研究中所述的适当条件下,在家进行药物流产是安全的。前瞻性群组研究并未显示各个国家以家为基础和以诊所为基础的药物流产在有效性或可接受性方面的差异。

Introduction

Medical abortion consists of using drugs to terminate a pregnancy. It is an important alternative to surgical methods.1 Although many different drugs have been used, alone and in combination, to induce abortion, a regimen composed of mifepristone plus misoprostol has been the one most widely used since mifepristone was first approved as an abortifacient in China and France in 1988.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends this drug combination, with an initial dose of mifepristone followed by misoprostol 36 to 48 hours later, for early medical abortion.2 In 2005, an estimated 26 million women worldwide used this drug combination to terminate their pregnancies.3

In home-based medical abortion, a health-care provider administers mifepristone at the clinic and the pregnant woman later takes misoprostol at home. This protocol is intended to simplify the medical abortion regimen. Home-based medical abortion may improve the acceptability of medical abortion by allowing for greater privacy than in-clinic abortion, giving women greater control over the timing of abortion (anytime before the seventh week of pregnancy) and making it possible for family members or friends to be present to provide emotional support.4,5 Home-based medical abortion also reduces the number of clinic visits required, and hence the burden on women and services.5 In studies from France, Sweden, Tunisia and the United States of America, the majority of women opted for home-based medical abortion when offered the choice between home and clinic.3 Self-administration of misoprostol is already common in France and the United States.6

Medical abortion has been practiced to varying degrees across different settings. Despite this, whether home-based methods are as effective as clinic-based methods remains unclear. Studies evaluating regimens consisting of mifepristone and misoprostol in various combinations suggest that home-based medical abortion is effective and safe. Clinical trials from Canada,7 Turkey8,9 and the United States10,11 report rates of complete abortion ranging from 91% to 98% for pregnancies up to 9 weeks when misoprostol is administered at home (Appendix A, available at: http://www.mariestopes.org/documents/Home-based%20Medical-Abortion-Systematic-Review-Appendix.pdf). Observational studies12–20 have also shown that home-based medical abortion is well accepted and effective, with 86–98% of women reporting satisfaction with the method and complete abortion achieved in 87% to 98% of cases. However, none of these studies has compared home-based medical abortion with clinic-based protocols. To fill this research gap, in this paper we review the evidence on the comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion practised at home and in clinic.

Methods

Study selection

In this review we searched for published studies on home-based medical abortion that tested different drugs, routes of administration and doses or regimens. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies were eligible for inclusion; service evaluations, case series and review articles were excluded. The inclusion criteria were: (i) a comparison between home-based and clinic-based medical abortion;(ii) a prospective assessment of outcomes; and (iii) reporting of the primary outcome of interest.

Participants

Participants of interest were women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in resource-rich or resource-limited settings who were seeking an abortion.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of successful abortions (i.e. complete evacuation of the uterine contents without surgery). Other outcomes of interest were acceptability and the development of side-effects, which included bleeding, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, pain and infection. Mortality was expected to be low.2 There were three common measures of acceptability: satisfaction with the method, likelihood of choosing it again and likelihood of recommending it to a friend.21

Search strategy

We developed a search strategy based on search terms and filters used by the Cochrane Fertility Regulation Group22 (Table 1). Ovid MEDLINE (1950–December 2009), EMBASE (1980–2010), Popline (2004–2010) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1990–2010) were searched electronically. The following web sites were hand searched for relevant publications: Marie Stopes International, Ipas, Gynuity, Population Council, the International Consortium for Medical Abortion and Google Scholar. Searching was limited to publications from 1990 or later. No limits were placed on language.

Table 1. List of databases and search termsa used in systematic review of studies comparing home-based and clinic-based medical abortion.

| Search | Medline | Embase | Popline | Cochrane central register of controlled trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp abortion, induced/ OR abortion.mp OR pregnancy termination.mp OR termination of pregnancy.mp | exp abortion/ OR exp medical abortion/ OR abortion.mp. OR exp induced abortion/ OR pregnancy termination.mp. OR exp pregnancy termination/ OR termination of pregnancy.mp | abortion/ medical abortion/ induced abortion/ pregnancy termination/ termination of pregnancy | abortion OR medical abortion OR induced abortion OR pregnancy termination OR termination of pregnancy |

| 2 | Mifepristone.mp. OR exp Mifepristone/ OR misoprostol.mp. OR exp Misoprostol/ OR methotrexate.mp. OR exp Methotrexate/ OR exp Dinoprost/ OR dinoprost*.mp OR carboprost.mp. OR exp Carboprost/ OR sulprostone.mp OR gemeprost.mp OR meteneprost.mp OR lilopristone.mp OR onapristone.mp OR epostane.mp OR exp Oxytocin/ OR oxytocin.mp OR RU 486.mp OR mifegyne.mp | Mifepristone.mp. OR exp mifepristone/ OR misoprostol.mp. OR exp Misoprostol/ OR methotrexate.mp. OR exp Methotrexate/ OR exp Dinoprost/ OR dinoprost*.mp OR carboprost.mp. OR exp Carboprost/ OR sulprostone.mp OR gemeprost.mp OR meteneprost.mp OR lilopristone.mp OR onapristone.mp OR epostane.mp OR exp Oxytocin/ OR oxytocin.mp OR RU 486.mp OR mifegyne.mp | Mifepristone/ Misoprostol/ Methotrexate/ Dinoprost*/ Carboprost/ sulprostone / gemeprost / meteneprost / lilopristone / onapristone / epostane / Oxytocin/ RU 486 / mifegyne | Mifepristone OR Misoprostol OR Methotrexate OR Dinoprost* OR Carboprost OR sulprostone OR gemeprost OR meteneprost OR lilopristone OR onapristone OR epostane OR Oxytocin OR RU 486 OR mifegyne |

| 3 | home.mp OR (home adj2 use*).mp OR (home adj2 administrat*).mp | exp home/ OR home.mp OR (home adj2 use*).mp OR (home adj2 administrat*).mp | home / home use* / home administrat* | home OR home use* OR home administrat* |

| 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | |

| Results | 88 | 104 | 108 | 17 |

a Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms; exp indicates exploded MeSH term; adj indicates adjacency; asterisk (*) indicates unlimited truncation.

Validity assessment

Open-label trials and prospective cohort studies were eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if outcome data were collected retrospectively.

Study quality

Studies were assessed for quality based on a scale adapted from the Newcastle−Ottawa Scale. They were awarded points based on:

Selection bias: “A” if same inclusion criteria for both study arms and “I” if different eligibility criteria for each study arm or if criteria unclear;

Control for confounders: “A” if study controlled for gestational age in design/analysis (gestational age is an important confounder; previous reviews have indicated lower efficacy in more advanced pregnancies);23 “I” if no adjustment for confounders or this unclear.

Assessment of gestational age: “A” if gestational age determined according to standard protocol (i.e. interview, bimanual exam and/or ultrasound); “I” if not assessed or inadequately assessed; and

Adequacy of follow-up: “A” if all study participants accounted for or if ≤ 10% lost to follow up; “I” if no description of those lost to follow-up and if drop-out rate > 10%.

To be categorized as high quality, studies had to score positively on selection bias, assessment of gestational age and adequacy of follow-up, as we felt that these three categories could have the most direct influence on the outcomes and study design.

Data abstraction

Two independent reviewers screened and extracted the data using a pre-designed form. A researcher who fluently spoke French and English translated the French-language papers. We made three attempts within one month to contact the authors of studies whose eligibility for inclusion depended on unpublished information.

We recorded the number of women recruited to each intervention group and the number of complete abortions. The drugs used, dose and route of administration were noted, along with each study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used study participant characteristics at baseline and inclusion/exclusion criteria to qualitatively assess clinical heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

The principal measure of effect was the odds of having a successful medical abortion at home relative to the odds of having a successful medical abortion in clinic and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of this odds ratio (OR). We calculated the odds of having a successful abortion using the number of women recruited for each study and an intention-to-treat approach. We synthesized effectiveness in a meta-analysis, specifying a random-effects model to produce a pooled OR and CI. This model was selected a priori to incorporate the effect of trial heterogeneity among prospective studies from different settings. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using χ2 tests and I2 statistics. The following sensitivity analyses were carried out: (i) separate analysis of high-quality studies to explore the effect of biases on study heterogeneity; (ii) analyses by maximum gestational age, and (iii) analyses by resource-rich versus resource-limited study setting.

We present a forest plot showing relative risks and 95% CIs for the primary outcome. Owing to the small number of studies included in the data synthesis, we did not assess publication bias. Analyses were carried out using Stata version 11 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, USA).

Results

Description of included studies

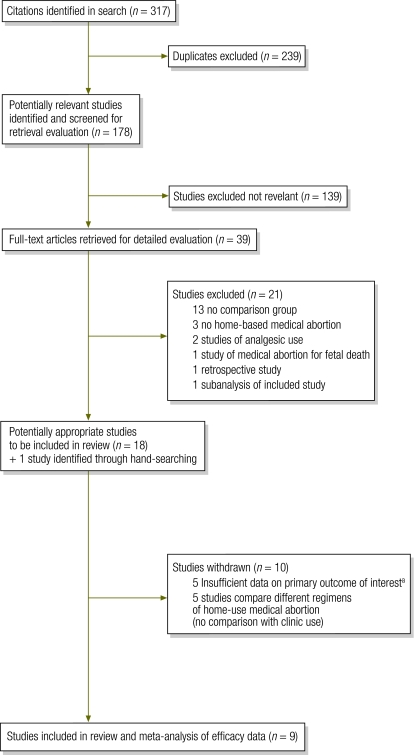

Nine studies were included in this review (Fig. 1) (one study was conducted in both Tunisia and Viet Nam and we present the findings separately for each setting). All were prospective cohort studies and included a total of 4522 participants (3478 home users, 1044 clinic users) (Table 2). The studies were carried out in Albania (n = 409), France (n = 714 women), India (n = 599), Nepal (n = 400), Tunisia (n = 518), Turkey (n = 208) and Viet Nam (n = 1674), between 199724–2008.25,31

Fig. 1.

Summary of study selection for systematic review of studies comparing home-based and clinic-based medical abortion

a These studies involved medical abortion at home and in clinic but did not compare outcomes by home versus clinic status; data for this comparison were unavailable.

Table 2. Studies comparing home-based and clinic-based medical abortion included in systematic review.

| Study | Mifepristone dose (mg); misoprostol dose (µg), [supplementary dose]; routea | No. of women recruited (no. lost to follow up) |

Complete abortion, no. (%) |

Complete abortion, OR (95% CI)b | Maximum gestational age (days) | Contact with health services | Women accompanied during home administration of misoprostol (%) | Comparative participant characteristics at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | C | H | C | ||||||||

| Akin et al. 2004,9 Turkey | 200; 400; oral | 104 (4) | 104 (3) | 92 (88.5) | 83 (79.8) | 1.94 (0.90–4.18) | 56 | 11.5% of clinic users vs 3.8% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits (P < 0.04) | 55 | No difference in age, education, marital status (married: n = 98 home; n = 96 clinic), gestational age, gravidity or abortion history | |

| Bracken et al. 2006,24 Albania | 200; 400; oral | 361; 6 | 48 (1) | 345 (97.2) | 46 (97.9) | 0.94 (0.21–4.21) | 56 | 4.2% of women made unscheduled clinic visits, no difference between groups; 27.1% called hotline, no difference between groups | 67.8 | No difference in age, education, marital status (married: n = 260 home; n = 36 clinic), gestational age, gravidity or abortion history | |

| Bracken et al. 2010,25 India | 200; 400; oral | 530 (21) | 69 (3) | 453 (85.5) | 61 (88.41) | 0.77 (0.36–1.68) | 56 | Not reported | 84.2 | No difference in gestational age, gravidity or abortion history. Home users were 1.6 y older than clinic users on average (P = 0.008); marital status not reported | |

| Dagousset et al. 2004,26 France | 600; 400 [400]; oral | 120 (0) | 289 (0) | 114 (95) | 286 (99)* | 0.20 (0.05–0.81) | 49 | 21.7% of home users called gynaecologist | All women (inclusion criterion) | Home users were older and more educated and fewer of them were primigravida; marital status not reported | |

| Elul et al. 2001,27 Viet Nam | 200; 400; oral | 106 (8) | 14 (0) | 102 (96) | 11 (80) | 6.96 (1.38–35.18) | 56 | 27% of clinic users vs 31% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits; 7% of clinic users vs 8% of home users called the clinic | 78 | No comparison reported; marital status not reported | |

| Elul et al. 2001,27 Tunisia | 200; 400; oral | 170 (4) | 25 (0) | 158 (93) | 22 (88) | 1.80 (0.47– 6.87) | 56 | 18% of clinic users vs 8% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits; 24% of clinic users vs 18% of home users called the clinic | 76 | No comparison reported; marital status not reported | |

| Hajri et al. 2004,28 Tunisia | 200; 400; oral | 241 (9) | 82 (0) | 233 (96.7) | 76 (92.7) | 2.30 (0.77–6.84) | 56 | 12.3% of clinic users vs 5.4% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits; 18.5% of clinic users vs 14.6% of home users called study hotline | ~75 | No difference in age, marital status (married: n = 193 home; n = 193 clinic), gestational age, parity or abortion history. Home users were more educated than clinic users by an average of 1.4 y (P = 0.02) | |

| Karki et al. 2009,29 Nepal | 200; 400; oral | 323 (31) | 77 (2) | 267 (91.4) | 68 (90.7) | 0.63 (0.30–1.34) | 56 | 16.9% of clinic users vs 11.1% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits; 20.8% of clinic users vs 19.5% of home userscalled the clinic hotline | 77.9 | Similar in age, education, gestational age and abortion history (no statistical test reported); marital status not reported | |

| Ngoc et al. 2004,30 Viet Nam | 200; 400; oral | 1380 (24) | 174 (0) | 1231 (88.6) | 164 (94.3)* | 0.50 (0.26–0.98) | 56 | 4.6% of clinic users vs 9.0% of home users made unscheduled clinic visits (P = 0.047); 6.9% of clinic users vs 15.5% of home users called hotline (P = 0.002) | 73.4 | No difference in age, marital status (married: n = 1 244 home; n = 158 clinic) and abortion history. Home users were more educated (< 0.001), had lower maximum gestational age (0.001) and higher gravidity (< 0.001), and fewer of them were primigravida (0.001) | |

| Provansal et al. 2009,31 France | 600; 400 [400]; oral | 143 (30) | 162 (64) | 124 (86.7) | 155 (95.8)* | 0.30 (0.12– 0.72) | 49 | Not reported | All women (inclusion criterion) | No difference in abortion history. Home users were older (P < 0.001) and had higher gravidity (< 0.001) and higher parity (P < 0.001); fewer of them were primigravida (< 0.01). Marital status not reported | |

| Total | 3478 | 1044 | 3119 (89.7) | 972 (93.1) | – | – | – | – | – | ||

C, clinic; CI, confidence interval; H, home; OR, odds ratio; *P < 0.05.

a Delay to misoprostol is 48 hours except in Provansal et al. (36–48 hours) and Dagousset et al. (unspecified); supplementary dose of misoprostol administered to women in clinic-based groups if no expulsion of product within 3 hours of first misoprostol dose.

b Odds ratio: odds of complete abortion without surgery in women who used home-based relative to the odds in women who underwent clinic-based abortion.

Study participants

The mean age of study participants ranged from 24.7 to 32.2 years. The maximum gestational age was 56 days in seven studies and 49 days in the two French studies. Gestational age was assessed by last menstrual period (LMP) and confirmed by clinical examination.

One Vietnamese study30 reported that home users were more educated and had a lower gestational age and higher gravidity on average, and that fewer of them were primigravidas when compared with clinic users. An Indian study reported that home users were 1.6 years older on average than clinic users (P = 0.008).25 The Tunisian study indicated that women using the home-based abortion method were more educated than those who opted for a clinic-based method.28 One study did not compare participant characteristics at baseline.27

Interventions

In all studies, oral mifepristone and misoprostol were used in combination to produce a medical abortion. In seven studies. 200 mg of mifepristone were used, while in the two French studies 600 mg were used.26,31 The time between mifepristone and misoprostol administration was 48 hours in seven studies, 36–48 hours in one French study31 and unspecified in another study.26 All studies used misoprostol 400 µg, given as two tablets of 200 µg where specified.9,24,26,28,30 In all studies, women were given mifepristone at the clinic but could choose between taking misoprostol at home or returning to take it at the clinic. All protocols detailed the use of painkillers (paracetamol, codeine or ibuprofen), which women were advised to take as needed. In seven studies women were followed up 2 weeks after mifepristone administration, while in one study they were followed up at 10–20 days.31

Six studies required that participants live or work within 1 hour of the study site.24,26,27,29–31 In the French studies, women who lived farther than 1 hour away from the referral hospital were ineligible for the home-based protocol but were included in the study.

Study quality

The quality assessment based on four criteria described previously resulted in seven studies being categorized as high quality and two as low quality. Two studies scored 4/4,24,30 five studies scored 3/49,25,27–29 and the two French studies scored 1/4.26,31 (Appendix B, available at: http://www.mariestopes.org/documents/Home-based%20Medical-Abortion-Systematic-Review-Appendix.pdf).

Complete abortion

Among the 3478 women who took misoprostol at home, the proportion who succeeded in having a complete abortion ranged from 86% in India25 to 97% in Albania.24 The average success rate in this group was 89.7% (95% CI: 88.7–90.7%) (Table 2). Among the 1044 women who took misoprostol in clinic, the success rate ranged from 80% in Turkey9 to 99% in France.26 The average success rate in this group was 93.1% (95% CI: 91.4–94.5%). The ORs for complete abortion at home versus in a clinic showed no difference in effectiveness in five studies.9,24,25,28,29 In three studies (two French,26,31 one Vietnamese)30 medical abortion in clinic settings was found to be more effective, while in the study conducted in both Tunisia and Viet Nam abortion at home proved more effective (OR: 2.9; 95% CI: 1.1–8.1).27 Pooled data from all nine studies showed no evidence of a difference in complete abortion rates (OR: 0.8; 95% CI: 0.5–1.5). However, study heterogeneity was high (I2: = 69.4%).

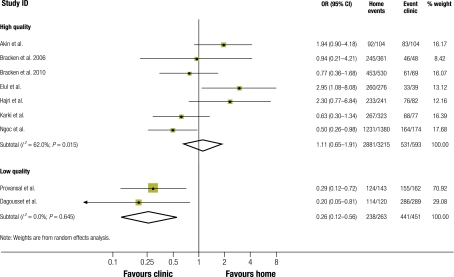

Subgroup analyses by study quality, maximum gestational age and study setting were equivalent, as the two studies from France also had low quality assessment scores and a maximum gestational age of 49 days (versus 56 days in the other studies). Pooled analysis of the seven high-quality studies showed no difference in complete abortion rates between women who took misoprostol at home (n = 3215) and those who took it in clinic (n = 593) (OR: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.7–1.9; I2: 62.0%) (Fig. 2). Pooled analysis of the findings of the two French studies indicated a higher rate of successful abortion among women who took misoprostol in clinic (n = 263 and 451) (OR: 0.2; 95% CI: 0.1–0.6).

Fig. 2.

Forest plota comparing rates of complete abortion in women who underwent home-based and clinic-based medical abortion

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

a Pooled data from all nine studies showed no evidence of a difference in complete abortion (odds ratio: 0.8; 95% confidence interval: 0.5–1.5).

Side-effects and complications

Side-effects were inconsistently reported across studies (Table 3). Pain and cramping were experienced by > 90% of women and lasted from 0.5 to 3 days.24 Pooled analysis of the mean number of days of pain from three studies indicated that pain lasted 0.3 days longer in women who took misoprostol at home (n = 1761) than in those who took misoprostol in clinic (n = 297) (weighted mean difference, WMD: 0.3 days; 95% CI: 0.1–0.5).9,24,30 Vomiting was reported by 12–34% of women24,29 and lasted 0.3 days longer in women who took misoprostol at home (n = 1761) than in women who took misoprostol in clinic (n = 297) (WMD: 0.32; 95% CI: 0.1–0.5). Fever also lasted longer in the former (n = 2058) than in the latter (WMD: 0.3 days; 95% CI: 0–0.6). Pooled analysis (n = 2058) showed no difference between home-based and clinic-based abortion in the reported duration of nausea (WMD: 0.3 days; 95% CI: −0.2 to 0.9), or the duration of heavy bleeding (WMD: 0.1 day; 95% CI: −0.1 to 0.4). In one study,30 women who took misoprostol at home were more likely to contact health services by phone or make unscheduled clinic visits (Table 2). In three other studies, women who took misoprostol in clinic were more likely to call clinic hotlines and make unscheduled visits than women who took misoprostol at home.9,27,29

Table 3. Side-effects and complications, their duration and the proportion of women who reported them among those who underwent home-based and clinic-based medical abortion.

| Study | Side-effect/complication |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain/cramps |

Nausea |

Vomiting |

Fever/chills |

Heavy bleedinga |

|||||||||||||||

| Mean no. of days (SD) |

% who reported | Mean no. of days (SD) |

% who reported | Mean no. of days (SD) |

% who reported | Mean no. of days (SD) |

% who reported | Mean no. of days (SD) |

% who reported | ||||||||||

| H | C | H | C | H | C | H | C | H | C | ||||||||||

| Akin et al. 20049 | 2.9 (3.1) | 2.6 (3.4) | NR | 2.0 (2.8) | 1.8 (2.0) | NR | 0.8 (2.0) | 0.4 (1.0) | NR | 1.0 (2.4) | 0.4 (0.7) | NR | 2.1 (2.3) | 1.7 (2.5) | NR | ||||

| Bracken et al. 200624 | 0.6 (1.2) | 0.5 (1.2) | 90.3 | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.4) | 62.7 | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.1) | 33.7 | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.3 (0.7) | 23.2 | 1.9 (1.7) | 2.0 (2.0) | NR | ||||

| Ngoc et al. 200430 | 1.7 | 1.4* | NR | 1.5 | 0.8* | NR | 0.6 | 0.2* | NR | 0.4 | 0* | NR | 2.5 | 2.4 | NR | ||||

| Karki et al. 200929 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.5 | NR | NR | 8.5 | NR | NR | NR | ||||

C, clinic; H, home; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation; *P < 0.05.

a Bleeding heavier than a normal menstrual bleed.

Serious complications were rare. Four women had severe bleeding that required transfusion. Two of these women had taken misoprostol at home;29 where the other two women took the misoprosotol was not reported.25 Suspected infection requiring hospitalization occurred in one case,25 but where the woman took the misoprostol was not reported.

Acceptability

In reporting acceptability, most studies used the following criteria: satisfaction with the method (8 studies); the likelihood of choosing the method again (9 studies); and the likelihood of recommending medical abortion to a friend (4 studies) (Table 4). Of the women who underwent a home-based medical abortion (n = 3138), 84–99% were satisfied. Their average satisfaction rate was 88.4% (95% CI: 86.9–89.1). Among women who took misoprostol in clinic (n = 867), 72–97% were satisfied. Their average satisfaction rate was 85.6% (95% CI: 82.6–87.4). Pooled analysis showed no difference in satisfaction rates between women taking misoprostol at home or in clinic (OR: 1.46; 95% CI: 0.59–3.60; I2: 82.2%).

Table 4. Acceptability of home-based and clinic-based medical abortion in studies included in systematic review comparing home-based and clinic-based medical abortion.

| Study | Satisfied or highly satisfied with method (%) |

Would choose method again (%) |

Would recommend method to a friend (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | C | MD | H | C | MD | H | C | MD | |||

| Akin et al. 20049 | NR | NR | NR | 94.0 | 44.4 | 49.6 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Bracken et al. 200624 | 90.6 | 90.3 | 0.3 | 95.6 | 40.4 | 55.2 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Bracken et al. 201025 | 90.7 | 92.3 | −1.6 | 95.3 | 67.1 | 28.2 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Dagousset et al. 200426 | 98.5 | 72.2 | 26.3 | 77.5 | 59.5 | 18.0 | 78.8 | 50.67 | 28.13 | ||

| Elul et al. 2001,27 Viet Nam | 91.0 | 87.0 | 4.0 | 93.0 | 33.0 | 60.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Elul et al. 2001,27 Tunisia | 94.0 | 91.0 | 3.0 | 96.0 | 69.0 | 27.0 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Hajri et al. 200428 | 96.3 | 89.4 | 6.9 | 96.5 | 89.4* | 7.1 | 97.2 | 92.5* | 4.7 | ||

| Karki et al. 200929 | 88.3 | 97.2 | −8.9 | 90.7 | 93.2 | −2.5 | 92.9 | 98.6 | −5.7 | ||

| Ngoc et al. 200430 | 83.6 | 91.4 | −7.8 | 96.1 | 38.5 | 57.6 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Provansal et al. 200931 | 98.0 | 92.9 | 5.1 | 91.1 | 79.6* | 11.5 | 89.1 | 85.0 | 4.1 | ||

C, clinic; H, home; MD, mean difference; NR, not reported; *P < 0.05.

About 78–97% of home users (mean 94.4%; n = 3239) and 40–93% of clinic users (mean 61.6%; n = 963) stated that they would choose medical abortion again. Women who took misoprostol at home were seven times more likely to choose medical abortion again than women who took misoprostol in clinic (pooled OR: 7.1; 95% CI: 2.7–18.6), although heterogeneity was high (I2: 94%). Four studies reported the number of women who would recommend medical abortion to a friend (n = 1194).26,28,29,31 The pooled OR was 2.8 (95% CI: 0.5–17.3). Thus, no difference was found in this respect between women who took misoprostol at home and in clinic.

Discussion

Medical abortion is an important alternative to surgical methods for the termination of pregnancy. Our review is the first to systematically compare home-based to clinic-based medical abortion. Other reviews have compared medical abortion methods by regimen22,23 and gestational age.23 We have shown that the rate of complete abortion among women using home-based medical abortion across diverse study settings is high (~90%), and there is no evidence of a difference in effectiveness when compared to clinic-based protocols. The rate of complete abortion reported in our review is similar to the rates reported in other reviews. For example, the Cochrane Review of medical methods for first trimester abortion noted success rates of > 90% in all studies.22 Loss to follow-up was low in the included studies (4% in home-based groups, and 6% in clinic-based groups).

This review has limitations. Meta-analysis of the findings of non-randomized studies increases the possibility of biases,32 particularly self-selection bias stemming from the fact that women could choose between home-based and clinic-based medical abortion. As an illustration, women wanting to keep the procedure confidential and concealed from family members would be more likely than others to choose clinic-based abortion. Only one study reported the findings with adjustment for potential confounders.30 Our reported effect sizes are unadjusted and residual confounding and other biases are likely to have affected the estimates and study heterogeneity. Thus, the pooled estimates should be interpreted with caution.

Data from this review are limited to pregnancies no longer than 56 days. Eight of the nine included studies assessed gestational age from the date of the last menstrual period, which, according to a recent trial (n = 4484) that compared this method with pelvic bimanual and ultrasound, is effective in determining gestational age for early medical abortion.33 In all studies, participants were required to live or work within 1 hour of the study site and to be in good health, and in several studies they were required to have access to a telephone. However, there was no stipulation regarding the means of transportation for getting to the study site or the presence of another person at home in case of emergency. Women participating in studies were also screened for allergies to mifepristone and misoprostol. The effectiveness of home-based medical abortion in non-research settings without the precautionary measures and support systems that were most likely in place in these and other studies, essential for compliance with ethical norms, may be less satisfactory. From the data provided in this paper it is not possible to determine just how safe medical abortion practised at home would be if back up safety measures (e.g. easy access to a health facility, consultation by phone) were absent or more relaxed. Home-based medical abortion does not preclude prior screening for ectopic pregnancy, which is a standard of care even in resource-limited settings.34 Because of the inclusion of the two French studies, both categorized as low quality, this review was unable to provide robust estimates of the effectiveness of home-based medical abortion in developed settings.

Safety data from the included studies showed that of 3478 women who underwent abortion at home, two experienced heavy bleeding requiring transfusion. Thus, complications arising from use of misoprostol at home were rare. Two cases of heavy bleeding and one case of suspected infection were reported in the Indian study.25 However, the paper did not specify where the misoprostol was administered. If we assume that it was always administered at home the proportions of women affected (0.03% with infection, 0.1% with heavy bleeding) are comparable to the proportions reported in other reviews.3,35 Most women experienced pain and cramping after misoprostol administration. Women in the home-based groups reported experiencing pain and vomiting for slightly longer (0.3 days) than those in clinic-based groups, but they did not have more contact with health services. In the included studies, women who took misoprostol at home used self-report study cards to record any side-effects, while those who aborted in clinic were observed in the facility. Therefore, the safety data may be subject to reporting bias. Data on side-effects were also inconsistently reported across studies and this limits their generalizability.

Women who practised home-based medical abortion appeared satisfied and likely to choose the method again. Acceptability is subject to the influence of costs and convenience, data that were unavailable for the included studies. Furthermore, the included studies did not report on other factors, such as tolerance for bleeding and pain, that could have affected acceptability.

Our findings only apply to pregnancies up to 56 days and to the oral use of mifepristone–misoprostol. Data from our review cannot be generalized to settings where mifepristone is unavailable or where misoprostol is used in higher doses to induce abortion. It is also important to emphasize that the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen is not an alternative contraceptive method.

Implications

There is no evidence that home-based medical abortion is less effective, safe or acceptable than clinic-based medical abortion. Simplified protocols could give greater access to medical abortion to women living in restrictive and/or resource-limited settings where mortality related to unsafe abortion remains high.36 Adequate safety measures and support systems should be in place before home-based medical abortion can be offered. To further clarify the comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of home-based medical abortion, further studies should be conducted to explore different regimens, routes of administration and its use for gestational ages, as well as on the use of misoprostol only for home-based medical abortion, given the high cost of mifepristone and the fact that its use is restricted in many settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nathalie Kapp from the Department of Reproductive Health and Research of the World Health Organization for her critical review of the manuscript and Kristen Hopkins from Marie Stopes International (MSI) for translating the French-language articles. They also thank the authors of the original studies who provided additional information for this review.

Thoai D Ngo is also based within the Research and Metrics Team at MSI, and Min Hae Park is also affiliated with the Department of Epidemiology and Population Health of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Funding:

The Research and Metrics Team at Marie Stopes International provided funding for this review.

Competing interests:

TDN and MHP work for Marie Stopes International, an organization that provides medical abortion procedures in the United Kingdom and globally. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: (i) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; (ii) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in this review; (iii) no spouses, partners or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in this review; (iv) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to this review.

References

- 1.Creinin MD. Medical abortion regimens: historical context and overview. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(Suppl):S3–9. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berer M. Medical abortion: issues of choice and acceptability. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berer M. Medical abortion: a fact sheet. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13:20–4. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(05)26212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark WH, Gold M, Grossman D, Winikoff B. Can mifepristone medical abortion be simplified? A review of the evidence and questions for future research. Contraception. 2007;75:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho PC. Women’s perceptions on medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RK, Henshaw SK. Mifepristone for early medical abortion: experiences in France, Great Britain and Sweden. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:154–61. doi: 10.2307/3097714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shannon C, Wiebe E, Jacot F, Guilbert E, Dunn S, Sheldon WR, et al. Regimens of misoprostol with mifepristone for early medical abortion: a randomised trial. BJOG. 2006;113:621–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akin A, Dabash R, Dilbaz B, Aktün H, Dursun P, Kiran S, et al. Increasing women’s choices in medical abortion: a study of misoprostol 400 microg swallowed immediately or held sublingually following 200 mg mifepristone. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2009;14:169–75. doi: 10.1080/13625180902916020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akin A, Blum J, Ozalp S, Onderoglu L, Kirca U, Bilgili N, et al. Results and lessons learned from a small medical abortion clinical study in Turkey. Contraception. 2004;70:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creinin MD, Fox MC, Teal S, Chen A, Schaff EA, Meyn LA, MOD Study Trial Group A randomized comparison of misoprostol 6 to 8 hours versus 24 hours after mifepristone for abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:851–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000124271.23499.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creinin MD, Schreiber CA, Bednarek P, Lintu H, Wagner M-S, Meyn LA, Medical Abortion at the Same Time (MAST) Study Trial Group Mifepristone and misoprostol administered simultaneously versus 24 hours apart for abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:885–94. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258298.35143.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pymar HC, Creinin MD, Schwartz JL. Mifepristone followed on the same day by vaginal misoprostol for early abortion. Contraception. 2001;64:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark WH, Hassoun D, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Fiala C, Winikoff B. Home use of two doses of misoprostol after mifepristone for medical abortion: a pilot study in Sweden and France. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2005;10:184–91. doi: 10.1080/13625180500284581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faucher P, Baunot N, Madelenat P. Efficacité et acceptabilité de l’interruption volontaire de grossesse par méthode médicamenteuse pratiquée sans hospitalisation dans le cadre d’un réseau ville–hôpital: étude prospective sur 433 patientes. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005;33:220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.02.021. [The efficacy and acceptability of mifepristone medical abortion with home administration misoprostol provided by private providers linked with the hospital: A prospective study of 433 patients] [French. ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiala C, Winikoff B, Helström L, Hellborg M, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Acceptability of home-use of misoprostol in medical abortion. Contraception. 2004;70:387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamoda H, Ashok PW, Flett GMM, Templeton A. Home self-administration of misoprostol for medical abortion up to 56 days’ gestation. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2005;31:189–92. doi: 10.1783/1471189054483915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jørgensen H, Qvigstad E, Jerve F, Melseth E, Eskild A, Nielsen CS. Induced abortion at home. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:2367–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blum J, Hajri S, Chélli H, Mansour FB, Gueddana N, Winikoff B. The medical abortion experiences of married and unmarried women in Tunis, Tunisia. Contraception. 2004;69:63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuni N, Chandrashekhar TS. Early pregnancy termination with a simplified mifepristone: Medical abortion outpatient regimen. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2009;7:209–12. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v7i3.2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guengant JP, Bangou J, Elul B, Ellertson C. Mifepristone-misoprostol medical abortion: home administration of misoprostol in Guadeloupe. Contraception. 1999;60:167–72. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(99)00074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho PC. Women’s perceptions on medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulier R, Gulmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng L, Campana A. Medical methods for first trimester abortion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(Issue 2):CD002855. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn JG, Becker BJ, MacIsaa L, Amory JK, Neuhaus J, Olkin I, et al. The efficacy of medical abortion: a meta-analysis. Contraception. 2000;61:29–40. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(99)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bracken H, Gliozheni O, Kati K, Manoku N, Moisiu R, Shannon C, et al. Medical Abortion Research Group Mifepristone medical abortion in Albania: results from a pilot clinical research study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11:38–46. doi: 10.1080/13625180500361058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bracken H, Family Planning Association of India (FPAI)/Gynuity Health Projects Research Group for Simplifying Medical Abortion in India Home administration of misoprostol for early medical abortion in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;108:228–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dagousset I, Fourrier E, Aubény E, Taurelle R. Enquête d’acceptabilité du misoprostol à domicile pour interruption volontaire de grossesse par méthode médicamenteuse. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2004;32:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2003.11.005. [Use of misoprostol for medical abortion: a trial of the acceptability for home use.] [ French.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elul B, Hajri S, Ngoc NN, Ellertson C, Slama CB, Pearlman E, et al. Can women in less-developed countries use a simplified medical abortion regimen? Lancet. 2001;357:1402–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajri S, Blum J, Gueddana N, Saadi H, Maazoun L, Chélli H, et al. Expanding medical abortion in Tunisia: women’s experiences from a multi-site expansion study. Contraception. 2004;70:487–91. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karki C, Pokharel H, Kushwaha A, Manandhar D, Bracken H, Winikoff B. Acceptability and feasibility of medical abortion in Nepal. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;106:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngoc NTN, Nhan VQ, Blum J, Mai TTP, Durocher JM, Winikoff B. Is home-based administration of prostaglandin safe and feasible for medical abortion? Results from a multisite study in Vietnam. BJOG. 2004;111:814–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Provansal M, Mimari R, Gregoire B, Agostini A, Thirion X, Gamerre M. Interruption volontaire de grossesse médicamenteuse à domicile et à l’hôpital: étude d’efficacité et d’acceptabilité. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009;37:850–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2009.07.016. [Medical abortion at home and at hospital: a trial of efficacy and acceptability] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Wells GA. Chapter 13: Including non-randomized studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.2 (updated September 2009). The Cochrane Collaboration 2009. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org [accessed 16 February 2011].

- 33.Bracken H, Clark W, Lichtenberg ES, Schweikert SM, Tanenhaus J, Barajas A, et al. Alternatives to routine ultrasound for eligibility assessment prior to early termination of pregnancy with mifepristone-misoprostol. BJOG. 2011;118:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Hertzen H, Baird D, Bellagio Study and Conference Center Frequently asked questions about medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sitruk-Ware R. Mifepristone and misoprostol sequential regimen side effects, complications and safety. Contraception. 2006;74:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]