Abstract

Abortion, placental and fetal colonization, and levels of gamma interferon were analyzed for four Chlamydophila abortus strains presenting antigenic variations in a mouse model. Expression of virulence of these strains varied and indicated that abortion was not directly related to the number of bacteria in the placenta, and thus, other factors may have an important role in activating the abortion process.

Chlamydophila abortus, an obligate intracellular bacterium, colonizes different types of placenta and causes enzootic abortion during the last trimester of gestation in ewes and goats. The bacteria also present a potential zoonotic risk to pregnant women (6, 15, 23, 37).

This species is considered to be very homogenous at genomic (10, 21, 29) and antigenic levels (31). However, little genomic divergence has been identified (2, 3, 32), although variations between strains have been related to cross-protection in mouse models (14, 27). As far as we are aware, only three strains of C. abortus, i.e., LLG and POS, isolated in Greece from an aborted goat and ewe, respectively (32), and AB16, isolated in France from an aborted ewe in a vaccinated flock (18), vary in terms of reactivity with monoclonal antibodies against the highly immunogenic (9, 33) polymorphic outer membrane proteins (POMP) (17, 36). In addition, LLG and POS differ from other abortive strains in inclusion morphology and reactivity with protective monoclonal antibodies (11) against the major outer membrane protein (36). The numerous copies of genes encoding POMP (13, 16, 17, 19) suggest an essential role of POMP in the survival of chlamydiae (22), perhaps in the avoidance of host immune defenses (34). These three strains might therefore present differences in virulence, and previous studies (32, 36) have reported that strain LLG was more infectious for chicken embryos and cell cultures than other strains.

Generally, virulence is defined by the capacity of a bacterium to infect and damage its host, although this definition does not fully take into account the importance of the colonization stage. In this study virulence was evaluated both by abortion and by the individual colonization of placentas and fetuses. In addition, in view of its harmful effects in placenta (12, 20, 24), the induction of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by the different strains was investigated. Indeed IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor cause inflammation and together are thought to threaten the maintenance of pregnancy.

To assess the virulence of the strains, 8-week-old female OF1 (Swiss IFFA Credo, l'Arbresle, France) mice were inoculated intraperitoneally at 11 days of gestation, estimated as described previously (1). As in natural infection in ewes, intraperitoneal inoculation in pregnant mice during mid-gestation resulted in placental colonization, causing abortion and bacterial shedding at the end of gestation (4). In the first experiment, 5 of 20 pregnant mice were sacrificed from each infected group. Placentas and fetuses were individually removed (1) and titrated. In the second experiment, the pooled placentas and fetuses from the uterine horns of 10 pregnant mice per group were titrated (25). Blood collected from 10 pregnant and 5 nonpregnant mice was used to evaluate IFN-γ induction.

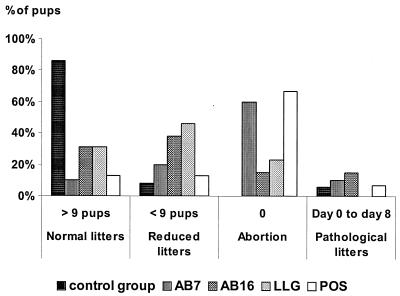

The average number of living mouse pups per litter of the 15 remaining mice per group was significantly lower for all inoculated strains than those of the control group (P < 0.0001), but it varied according to the strain. Mice inoculated with AB7 and POS did not differ significantly, with an average of 2.7 live pups per mother 8 days after birth. No difference was observed between AB16 and LLG under the same conditions, with 5.5 and 6.6 live surviving mice per litter, respectively (P = 0.43). However, there was a significant difference between groups AB16/LLG and AB7/POS (P < 0.0001), and the average numbers of live pups corresponded to four categories of birth. Inoculation of strains AB16 and LLG resulted in more “reduced litters” than real abortions, but they also resulted in some “pathological” and even normal litters (Fig. 1). AB7 and POS strains were the most virulent, since they mainly resulted in abortion.

FIG. 1.

Average number of mouse pups surviving at 8 days postbirth corresponded to four categories of birth. Fifteen mice per group were inoculated intraperitoneally with 4.3 × 105 PFU of AB7, 6.1 × 105 PFU of AB16, 5.5 × 105 PFU of POS, or 7 × 105 PFU of LLG. Twenty unchallenged mice were kept as the control group. The mice were placed in individual cages, and mouse pups were counted from birth until 8 days postbirth for pregnancy follow-up (26). According to our observations with 200 mice, the average number of living pups in a normal litter was 11.91 ± 0.21. When there were fewer than nine, the litter was considered “reduced.” Abortion was defined as no living pups at birth. However, when all the pups died before the eighth day, it was considered to be a “pathological litter.”

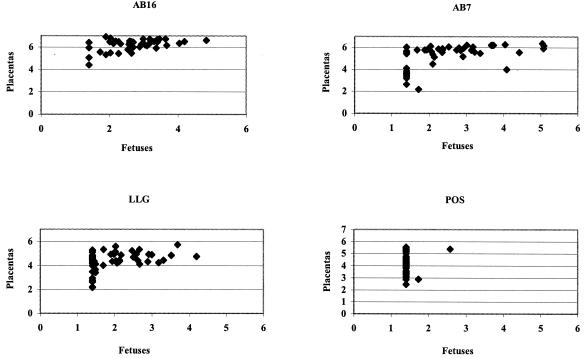

To examine whether abortion and reduced litters resulted from bacterial multiplication in placentas and fetuses, chlamydia were counted in these organs individually. All the placentas were infected irrespective of the strains inoculated but at different levels (Fig. 2). Strains AB16 and AB7 colonized the placenta and fetus more strongly than strains POS and LLG (P < 0.0001). Therefore, contrary to our hypothesis, abortions and reduced litters were not correlated with the level of placental and fetal infection. In utero-infected mouse pups survived after inoculation of AB16. Abortion was not directly related to the number of bacteria in the placenta, and it was probably not the lysis of infected placenta cells alone that was responsible for abortion. Other factors may play an important role in activating the abortion process. Inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, produced in response to infection at the maternal-fetal interface have been postulated to abrogate normal placentation and predispose the mother and fetus to adverse reproductive outcomes, including miscarriage and fetal growth restriction (7, 20). The role of IFN-γ in abortion in mice infected with C. abortus AB7 has been demonstrated in a knockout mouse model, since IFN-γ knockout mice aborted earlier than the wild-type mice in spite of a lower level of placental infection (I. Benchaîeb, personal communication).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of fetal and placental colonization after intraperitoneal inoculation of 5 mice at 11 days of pregnancy with 4.3 × 105 PFU of AB7, 6.1 × 105 PFU of AB16, 5.5 × 105 PFU of POS, or 7 × 105 PFU of LLG. Five days after challenge, placentas and fetuses from the same uterine horn were individually and aseptically removed (1). Organs were kept individually and homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline-DEAE dextran (0.01%), and titrated by PFU (25) and enumerating inclusion-forming units (IFU) on McCoy cells (4). The levels of placental colonization of mice inoculated with strains POS and LLG did not differ (4.05 and 4.60 log, respectively) (P = 0.13) (two-factor analysis of variance, strains-horn), but they were significantly less heavily infected than those of mice inoculated with AB7 (5.28 log) (P < 0.001) or AB16 (6.21 log) (P < 0.001) (two-factor analysis of variance, strains-horn). Strain AB16 colonized placentas and fetuses more strongly than strain AB7 (P < 0.001) (two-factor analysis of variance Strains-Horn). Only two fetuses were infected with the POS strain, whereas the LLG strain also resulted in many unaffected fetuses, which may explain the reduced litters. The placental colonization level of LLG was greater than that of POS, but the difference was not statistically significant.

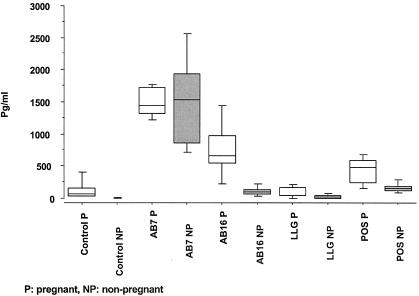

Infected mice produced IFN-γ for all strains, but different levels were recorded. Inoculation of the AB7 strain induced very high levels of IFN-γ in nonpregnant mice, significantly higher than for controls and the other strains (P < 0.05). There was no difference in the induction of IFN-γ by the AB16, POS, and LLG strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Levels of IFN-γ production in sera of C. abortus-infected pregnant and nonpregnant mice: 5.6 × 105 PFU of AB7, 7.2 × 105 PFU of AB16, 1.4 × 105 PFU of POS or 2.4 × 105 PFU of LLG for the 10 pregnant and 5 nonpregnant mice, and 3.4 × 105 PFU of AB7, 1.3 × 105 PFU of AB16, 3.8 × 105 PFU of POS, or 1.4 × 105 PFU of LLG for the 10 nonpregnant mice. Experiments were performed twice in nonpregnant mice with similar results. Serum IFN-γ production was evaluated by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using a murine commercial kit obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, Minn.). Results are expressed as the median and upper and lower quartiles. Levels of IFN-γ induced by AB7 differed significantly from those for controls and other strains (P < 0.05 [Kruskal-Wallis test]). AB7 and AB16 differed significantly in pregnant mice from controls (P < 0.05 [Kruskal-Wallis test]), but only AB16 induced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ in the blood of pregnant mice compared to nonpregnant mice (P = 0.04 [Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test]).

The levels of placental infection after inoculation with AB7 were similar to those evaluated by titration of pooled placentas or fetuses from the same uterine horn after intravenous inoculation of mice (28). Levels of AB16 in our experiment were similar to those of the strain that colonized placentas and fetuses most (28). In contrast, POS and LLG, which are undoubtedly C. abortus strains, gave the same kinds of results as strains belonging to the Chlamydophila pecorum species. Compared to other C. abortus strains, POS and LLG formed very small plaques of lysis in cell cultures, as for most C. pecorum strains, smaller than those caused by AB7 and AB16. Thus, the rates of multiplication of the strains in cells could be responsible for the differences in levels of placental and fetal colonization. The cycle of multiplication must be compared to demonstrate whether AB16 differs from other strains and whether their cycles are shorter. The differences in numbers of chlamydiae in placentas and fetuses could also be due to different levels of IFN-γ in the blood. Indeed, the influence of IFN-γ on the multiplication of chlamydiae has been clearly demonstrated (30), but the serum levels of IFN-γ in mice were not related to the number of Chlamydia bacteria in placentas and fetuses.

Hormones can influence whether cells differentiate into those producing Th1 or Th2 (8), suggesting that they have a contributory role in abortion (12, 35) by increasing production of IFN-γ (5). It would be interesting to verify whether the hormonal response is the same after inoculation of different strains of C. abortus.

In our mouse model, differences in strain virulence were observed in terms of abortive effect, placental and fetal colonization, and level of IFN-γ in the blood. These three criteria were not correlated. Interestingly, strain AB16, which multiplied most in placentas and fetuses, did not induce the greatest number of abortions or the highest levels of IFN-γ. It is not possible to extrapolate these results to ewes, since the placental anatomies of mice and ewes are different, and it would therefore be interesting to compare how the four strains multiply in ovine placentas. Before undertaking such a study, it is necessary to specify the roles of each of the different factors and the cytokines involved for mice. Such studies using the available tools for mice should identify the virulence mechanisms of Chlamydia. These differences in virulence between strains cannot be linked to the differences in the POMP, since POS and LLG, which are considered to be two homologous strains for pmp genes, both for inclusion morphology and for their reactivity with antibodies against POMP (17, 36), were not similarly abortive in mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Bernard for statistical analysis; P. Lechopier, H. Le Roux, and other staff members for animal husbandry; and Françoise Bernard for technical assistance. Maintenance and care of experimental animals were conducted in compliance with National Decree no. 2001-46 relating to animal testing in France.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Bosseray, N., and M. Plommet. 1980. Colonization of mouse placentas by Brucella abortus inoculated during pregnancy. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 61:361-368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boumedine, K. S., and A. Rodolakis. 1998. AFLP allows the identification of genomic markers of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains useful for typing and epidemiological studies. Res. Microbiol. 149:735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, A. S., M. L. Ammos, M. F. Lavin, A. A. Girjes, P. Timms, and J. B. Woolcock. 1988. Isolation and typing of a strain of Chlamydia psittaci from Angora goats. Aust. Vet. J. 65:288-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buendia, A. J., J. Sanchez, M. C. Martinez, P. Camara, J. A. Navarro, A. Rodolakis, and J. Salinas. 1998. Kinetics of infection and effects on placental cell populations in a murine model of Chlamydia psittaci-induced abortion. Infect. Immun. 66:2128-2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buendia, A. J., J. Sanchez, L. Del Rio, B. Garces, M. C. Gallego, M. R. Caro, A. Bernabe, and J. Salinas. 1999. Differences in the immune response against ruminant chlamydial strains in a murine model. Vet. Res. 30:495-507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buxton, D. 1986. Potential danger to pregnant women of Chlamydia psittaci from sheep. Vet. Rec. 118:510-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buxton, D., I. E. Anderson, D. Longbottom, M. Livingstone, S. Wattegedera, and G. Entrican. 2002. Ovine chlamydial abortion characterization of the inflammatory immune response in placental tissues. J. Comp. Pathol. 127:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carp, H., A. Torchinsky, A. Fein, and V. Toder. 2001. Hormones, cytokines and fetal anomalies in habitual abortion. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 15:472-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cevenini, R., M. Donati, E. Brocchi, F. De Simone, and M. La Placa. 1991. Partial characterization of an 89-kDa highly immunoreactive protein from Chlamydia psittaci A/22 causing ovine abortion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 65:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denamur, E., C. Sayada, A. Souriau, J. Orfila, A. Rodolakis, and J. Elion. 1991. Restriction pattern of the major outer-membrane protein gene provides evidence for a homogeneous invasive group among ruminant isolates of Chlamydia psittaci. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:2525-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Sa, C., A. Souriau, F. Bernard, J. Salinas, and A. Rodolakis. 1995. An oligomer of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia psittaci is recognized by monoclonal antibodies which protect mice from abortion. Infect. Immun. 63:4912-4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Entrican, G. 2002. Immune regulation during pregnancy and host-pathogen interactions in infectious abortion. J. Comp. Pathol. 126:79-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimwood, J., and R. S. Stephens. 1999. Computational analysis of the polymorphic membrane protein superfamily of Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Microb. Comp. Genomics 4:187-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnsons, F. W. A., and M. J. Clarkson. 1986. Ovine abortion isolates: antigenic variation detected by mouse infection, p. 129-132. In I. D. Aitken ID (ed.), Agriculture. Chlamydial diseases of ruminants. Report EUR 10056 EN. Commission of the European Communities, Luxembourg, Belgium.

- 15.Jorgensen, D. M. 1997. Gestational psittacosis in a Montana sheep rancher. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:191-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalman, S., W. Mitchell, R. Marathe, C. Lammel, J. Fan, R. W. Hyman, L. Olinger, J. Grimwood, R. W. Davis, and R. S. Stephens. 1999. Comparative genomes of Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Nat. Genet. 21:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King, A., and Y. W. Loke. 1999. The influence of the maternal uterine immune response on placentation in human subjects. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 58:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laroucau, K., A. Souriau, and A. Rodolakis. 2000. Isolation of new pmp sequence in serotype-1 Chlamydia psittaci strains, p. 38. In P. Saikkiu (ed.), Chlamydia research, vol. 4. Universitas Helsingiensis, Finland.

- 19.Longbottom, D., M. Russell, S. M. Dunbar, G. E. Jones, and A. J. Herring. 1998. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genes coding for the highly immunogenic cluster of 90-kilodalton envelope proteins from the Chlamydia psittaci subtype that causes abortion in sheep. Infect. Immun. 66:1317-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCafferty, M. C., S. W. Maley, G. Entrican, and D. Buxton. 1994. The importance of interferon-gamma in an early infection of Chlamydia psittaci in mice. Immunology 81:631-636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClenaghan, M., A. J. Herring, and I. D. Aitken. 1984. Comparison of Chlamydia psittaci isolates by DNA restriction endonuclease analysis. Infect. Immun. 45:384-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer, G. H. 2001. The highest priority: what microbial genomes are telling us about immunity. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 85:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pospischil, A., R. Thoma, M. Hilbe, P. Grest, D. Zimmermann, and J. O. Gebbers. 2002. Abortion in humans caused by Chlamydophila abortus (Chlamydia psittaci serovar 1). Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 144:463-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghupathy, R. 1997. Th1 type immunity is incompatible with successful pregnancy. Immunol. Today 18:478-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodolakis, A., and L. Chancerelle. 1977. Plaque assay for Chlamydia psittaci in tissue samples. Ann. Microbiol. 128B:81-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodolakis, A. 1983. In vitro and in vivo properties of chemically induced temperature-sensitive mutants of Chlamydia psittaci var. ovis: screening in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 42:525-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodolakis, A., and F. Bernard. 1984. Vaccination with temperature-sensitive mutant of Chlamydia psittaci against enzootic abortion of ewes. Vet. Rec. 114:193-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodolakis, A., F. Bernard, and F. Lantier. 1989. Mouse models for evaluation of virulence of Chlamydia psittaci isolated from ruminants. Res. Vet. Sci. 46:34-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodolakis, A., and A. Souriau. 1992. Restriction endonuclease analysis of DNA from ruminant Chlamydia psittaci and its relation to mouse virulence. Vet. Microbiol. 31:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rottenberg, M.E., A. Gigliotti-Rothfuchs, and H. Wigzell. 2002. The role of IFN-gamma in the outcome of chlamydial infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:444-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salinas, J., A. Souriau, F. Cuello, and A. Rodolakis. 1995. Antigenic diversity of ruminant Chlamydia psittaci strains demonstrated by the indirect microimmunofluorescence test with monoclonal antibodies. Vet. Microbiol. 43:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siarkou, V., A. F. Lambropoulos, S. Chrisafi, A. Kotsis, and O. Papadopoulos. 2002. Subspecies variation in Greek strains of Chlamydophila abortus. Vet. Microbiol. 85:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Souriau, A., J. Salinas, C. De Sa, K. Layachi, and A. Rodolakis. 1994. Identification of subspecies- and serotype 1-specific epitopes on the 80- to 90-kilodalton protein region of Chlamydia psittaci that may be useful for diagnosis of chlamydial induced abortion. Am. J. Vet. Res. 55:510-514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanzer, R. J., D. Longbottom, and T. P. Hatch. 2001. Identification of polymorphic outer membrane proteins of Chlamydia psittaci 6BC. Infect. Immun. 69:2428-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veith, G. L., and G. E. Rice. 1999. Interferon gamma expression during human pregnancy and in association with labour. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 48:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vretou, E., H. Loutrari, L. Mariani, K. Costelidou, P. Eliades, G. Conidou, S. Karamanou, O. Mangana, V. Siarkou, and O. Papadopoulos. 1996. Diversity among abortion strains of Chlamydia psittaci demonstrated by inclusion morphology, polypeptide profiles and monoclonal antibodies. Vet. Microbiol. 51:275-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong, S. Y., E. S. Gray, D. Buxton, J. Finlayson, and F. W. Johnson. 1985. Acute placentitis and spontaneous abortion caused by Chlamydia psittaci of sheep origin: a histological and ultrastructural study. J. Clin. Pathol. 38:707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]