Abstract

Cannabinoid CB2 agonists produce antinociception without central nervous system (CNS) side-effects. This study was designed to characterize the pharmacological and antinociceptive profile of AM1710, a CB2 agonist from the cannabilactone class of cannabinoids. AM1710 did not exhibit off-target activity at 63 sites evaluated. AM1710 also exhibited limited blood brain barrier penetration. AM1710 was evaluated in tests of antinociception and CNS activity. CNS side-effects were evaluated in a modified tetrad (tail flick, rectal temperature, locomotor activity and rota-rod). Pharmacological specificity was established using CB1 (SR141716) and CB2 (SR144528) antagonists. AM1710 (0.1–10 mg/kg i.p.) produced antinociception to thermal but not mechanical stimulation of the hindpaw. AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) produced a longer duration of antinociceptive action than the aminoalkylindole CB2 agonist (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) at maximally antinociceptive doses. Antinociception produced by the low (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) dose of AM1710 was blocked selectively by the CB2 antagonist SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.), whereas antinociception produced by the high dose of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) was blocked by either SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.) or SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.). AM1710 did not produce hypoactivity, hypothermia, tail flick antinociception, or motor ataxia when evaluated in the tetrad at any dose. In conclusion, AM1710, a CB2-preferring cannabilactone, produced antinociception in the absence of CNS side-effects. Thus, any CB1-mediated antinociceptive effects of this compound may be attributable to peripheral CB1 activity. The observed pattern of pharmacological specificity produced by AM1710 is consistent with limited blood brain barrier penetration of this compound and absence of CNS side-effects.

Keywords: cannabinoid, CB2, antinociception, tetrad, pain

1. Introduction

Activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptors produces antinociception in animal models of persistent pain (for review see Guindon and Hohmann, 2008). The CB2 receptor represents a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of pathological pain specifically because antinociceptive efficacy is observed in the absence of unwanted central nervous system (CNS) side-effects (Hanus et al., 1999; Malan et al., 2001). Relative to CB1 receptors, a paucity of CB2 receptors is detected in the CNS of naive animals. However, CB2 receptors are upregulated within the CNS in neuropathic pain states (Beltramo et al., 2006; Wotherspoon et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2003). Upregulation of CB2 receptors may contribute to the efficacy of CB2-specific agonists in treating neuropathic pain (for review see Guindon and Hohmann, 2008). Additional targets for drug development aimed at harnessing the analgesic potential of cannabinoid signaling systems while limiting CNS side-effects have also been described (Anand et al., 2009; Schlosburg et al., 2009).

A recently described class of cannabinoids, the cannabilactones, includes the CB2-preferring agonists AM1714 and AM1710. Cannabilactones are defined and differentiated from other classes of cannabinoids by the presence of a carbonyl group in place of the 6,6-dimethyl moiety associated with the classical tricyclic structure of cannabinoids (Khanolkar et al., 2007). Both AM1714 and AM1710 produce antinociception following local (i.paw) administration, suggesting that they produce antinociception, at least in part, through peripheral mechanisms (Khanolkar et al., 2007). We recently demonstrated that a cannabilactone CB2 agonist suppresses neuropathic nociception in a chemotherapy model of peripheral neuropathy through a CB2-specific mechanism (Rahn et al., 2008). However, despite the considerable therapeutic potential of these compounds, antinociceptive effects of the cannabilactones remain relatively uncharacterized. More work is necessary to characterize the in vivo pharmacological profile associated with cannabilactone administration and determine whether compounds of this class show limited CNS side-effects. It remains unknown whether systemic administration of cannabilactones such as AM1710 lack cardinal signs of CB1 receptor activation (e.g. hypothermia, hypoactivity, motor ataxia) or exhibit an unfavorable CNS profile. This examination is important for validating the therapeutic potential of the cannabilactones for the treatment of pain.

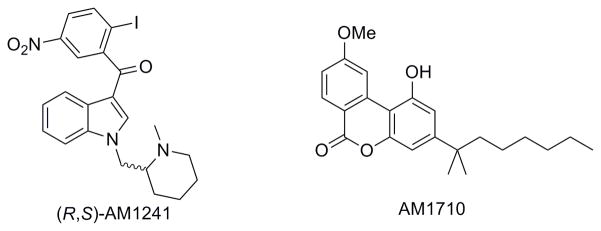

The present studies were conducted to evaluate the antinociceptive properties of the cannabilactone AM1710 (Fig 1) (Ki: CB1 vs. CB2: 360 nM vs. 6.7 nM) (Khanolkar et al., 2007), in tests of thermal (Hargreaves test) and mechanical (von Frey) sensitivity. The presence of centrally-mediated side-effects produced by AM1710 was evaluated using a modified tetrad (tail flick, rectal temperature, locomotor activity, rota-rod). Cardinal signs of cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation include antinociception in the tail-flick test, hypothermia, hypoactivity (measured by an activity meter) and motor ataxia in the rota-rod test (Malan et al., 2001; Martin et al., 1991). The pharmacological profile of AM1710 was compared with the prototypical CB2-specific agonist (R,S)-AM1241 (Ki: CB1 vs. CB2: 239.4 nM vs. 3.41 nM)(Thakur et al., 2005). (R,S)-AM1241 (Fig. 1) is a CB2 agonist from the aminoalkylindole class of cannabinoids that has been well-characterized in both rat and mouse (Hohmann et al., 2004; Ibrahim et al., 2006; Malan et al., 2001; Nackley et al., 2003; Rahn et al., 2007). Pharmacological specificity was determined using selective antagonists for CB1 (SR141716) and CB2 (SR144528). Central nervous system side-effects of AM1710 were compared to the mixed cannabinoid CB1/CB2 agonist WIN55,212-2, as well as (R,S)-AM1241 tested under identical conditions.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the aminoalkylindole (R,S)-AM1241 and the cannabilactone AM1710.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Two hundred fifteen adult male Sprague Dawley rats were used in behavioral experiments; one hundred sixteen (300–400 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) animals were used in studies of antinociception and ninety-nine (250–350 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) animals were used in the tetrad studies. All animals were maintained on a 12 hr light/12 hr dark cycle (7:00 – 19:00; lights on) in a temperature-controlled facility. Animals were single housed and had access to food and water ad libitum. Antinociceptive effects of the reference compound (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.; n= 8) have been reported previously by our group (Rahn et al., 2010). Data from this drug condition was collected concurrently with data presented in the current report. Animal experiments were conducted in full compliance with local, national, ethical and regulatory principles and local licensing regulations of Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International’s expectations for animal care and use/ethics committees.

Four male CD1 mice (initially weighing 16–18 g; Charles River Laboratories, Willmington, MA) were used for determining blood brain barrier penetration of AM1710. Mice were used for these studies because mouse CB2 shows 90% homology with rat CB2 (Yao and Mackie, 2009). The mice were acclimated to vivarium conditions for one week prior to experimentation. Mice were allowed access to food and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with public health and safety policies and followed the guidelines for the treatment of animals of the International Association for the Study of Pain (Zimmermann, 1983).

2.2. Drugs and Chemicals

AM1710 (3-(1′,1′-dimethylheptyl)-1-hydroxy-9-methoxy-6H-benzo[c]chromene-6-one), and (R,S)-AM1241 ((R,S)-(2-iodo-5-nitrophenyl)-[1-((1-methyl-piperidin-2-yl)methyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-methanone) were synthesized in the Center for Drug Discovery by two of the authors (by GT and AZ, respectively). SR141716 (5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4-methyl-N-(piperidin-1-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide) and SR144528 (5-(4-chloro-3-methylphenyl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl)-N-(1,3,3-trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide) were provided by NIDA. WIN55,212-2 ((R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3[(4-morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazinyl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate salt), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All drugs used in the behavioral studies were dissolved in a vehicle of 100% DMSO and delivered intraperitoneally (i.p.). This is the same vehicle that has been employed in previous work (Ibrahim et al., 2005; Malan et al., 2001; Nackley et al., 2003; Rahn et al., 2008). Cannabinoids and cannabinoid antagonists were dissolved in a volume of 1 ml/kg bodyweight with the following exception. Pharmacological specificity of AM1710 actions was determined by administering antagonists as pre-treatments 20 min prior to the agonist. In these conditions, each drug was administered in a volume of 0.5 ml/kg to ensure that all studies employed a uniform volume of DMSO.

2.3. In Vitro Screen

2.3.1. NovaScreen

The NovaScreen (Caliper Lifesciences, Hopkinton, MA) evaluated whether AM1710 exhibited off-target activity at 63 different targets including neurotransmitter-related G-protein coupled receptors, steroids, ion channels, second messenger-related prostaglandins, growth factors/hormones, brain/gut peptides and enzymes (See supplementary file for details of all targets tested).

2.3.2. Enzyme Assays

Rat ΔTM FAAH was expressed in E. coli cells and purified using the procedure disclosed by Patricelli and colleagues (1998). Recombinant hexa-histidine-tagged human MGL (hMGL) was expressed in E. coli cells and purified as reported by Zvonok and colleagues (2008a; 2008b). A high-throughput fluorometric screening assay for rFAAH inhibition using the fluorescent substrate, arachidonoyl 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin amide (AAMCA) was performed as previously reported (Ramarao et al., 2005). The MGL assays followed similar procedures using the fluorescent substrate arachidonoyl, 7-hydroxy-6-methoxy-4-methylcoumarin ester (AHMMCE) (Zvonok et al., 2008a). Prism software (GraphPad) was used to calculate IC50 values.

2.3.3. CB1 and CB2 binding assay

Competitive binding assays were performed using rat brain containing CB1 and HEK293 cells transfected with mouse CB2 (mCB2); membrane preparation has been previously described (Lan et al., 1999). Competition binding was between the compounds to be tested and [3H]CP55940 at a final concentration of 0.76 nM (specific activity 128 Ci/mmol; NIDA) incubated at 30μC for 1 hour with the respective membrane preparation. Non-specific binding was assessed in the presence of 100 nM CP55940. The interaction was terminated by rapid filtration of the reaction suspension (Unifilter GF/B-96 Well Filter Plates; Packard Instruments) followed by five washing steps with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM Tris-base, 5 mM MgCl2 with 0.5% BSA); bound radioactivity was determined using a Perkin Elmer TopCount Scintillation Counter. The results were analyzed using nonlinear regression to determine the actual IC50 of the ligand (Prism by GraphPad Software, Inc.) and the Ki values were calculated from the IC50 (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973). All data were in triplicate with IC50 and Ki values determined from at least two independent experiments.

2.4. Brain Barrier Penetration

2.4.1. Sample collection and plasma isolation

On the experimental day, AM1710 (1 mg/kg) was administered intravenously (i.v.) in a vehicle containing 3% DMSO in a 1:1:18 ratio of emulphor: ethanol: saline by injection into the lateral tail vein of mice (n = 4), weighing 25–30 g. Tissue samples were taken 15 minutes post-injection. Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation followed by decapitation so that trunk blood could be obtained and plasma separated by centrifugation. All samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

2.4.2. LC-MS/MS analysis

Tissues (plasma or brain) were extracted using a modified Folch extraction (Folch et al., 1957; Williams et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2010) and analyzed using a Thermo-Finnigan Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with an Agilent 1100 HPLC front-end. The mobile phases used were water (A) and methanol (B) in a gradient elution starting at 95% A, transitioning in a linear gradient to 5% A and held before returning to initial conditions. Samples of 10 μL each were injected onto a Phenomex Gemini C18 column (2 × 50 mm, 5μ) with a C18 guard column. AM1710 was detected using single reaction monitoring after APCI+ ionization.

2.5. General Behavioral Experimental Methods

Methods for assessing antinociception are described previously (Rahn et al., 2010). Baseline responses to mechanical stimulation of the hindpaw were evaluated at least 1 h prior to evaluation of baseline responses to thermal stimulation. In a subset of experiments (approximately 25%), the order of baseline testing was reversed (i.e. baseline responses to thermal stimulation were assessed at least 1 h prior to evaluation of baseline responses to mechanical stimulation). This modification enabled us to confirm that hypersensitivity to thermal or mechanical stimulation was not produced by the order of testing mechanical and thermal responses (data not shown). Following completion of baseline testing, all rats were returned to their home cages for approximately 2 h prior to administration of drug or vehicle. This delay was employed to ensure that animals did not develop sensitization to repeated testing.

CNS side-effects were evaluated in two separate groups of animals that comprised the “tetrad testing”. One set of animals was used for tail flick and rectal temperature assessment. The second set of animals was used for activity meter and rota-rod testing. Baseline tail flick latencies were assessed prior to baseline assessments of rectal temperature. Following baseline measurements, animals were returned to their home cages for approximately 2 h prior to drug or vehicle administration. Training for rota-rod took place on the two days preceding the test day. Only animals that met reliability criteria for the rota-rod (i.e. ability to walk on a rotating drum for 30 sec in two separate trials) on the test day received pharmacological treatments. Subjects that failed to meet the rota-rod criteria were subsequently used in the tail flick/rectal temperature or antinociception study after an appropriate delay (i.e. several days). Animals that passed criteria for inclusion in the rota-rod study were returned to their home cages for approximately 2 h prior to drug or vehicle administration. All studies were conducted by a single experimenter who was blinded to the drug condition. Animals were randomly assigned to drug or vehicle conditions.

2.5.1. Assessment of Mechanical Withdrawal Thresholds and Thermal Paw Withdrawal Latencies

Mechanical withdrawal thresholds were assessed using a digital Electrovonfrey Anesthesiometer (IITC model Alemo 2290–4; Woodland Hills, CA) equipped with a rigid tip (0.8 mm diameter). All efforts were made by the experimenter to maintain a constant rate of stimulus application across animals. Rats were placed underneath inverted plastic cages and positioned on an elevated mesh platform. Rats were allowed 10–15 min to habituate to the chamber prior to testing. Stimulation was applied to the midplantar region of the hind paw through the floor of a mesh platform. Mechanical stimulation was terminated upon paw withdrawal; consequently, there was no upper threshold limit set for termination of a trial. Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds are reported as the mean of duplicate determinations averaged across paws.

Paw withdrawal latencies to radiant heat were measured in duplicate for each paw using the Hargreaves test (Hargreaves et al., 1988) and a commercially available plantar stimulation unit (IITC model 336; Woodland Hills, CA). Rats were placed underneath inverted plastic cages positioned on an elevated glass platform. Rats were allowed 10–15 min to habituate to the chamber prior to testing. Radiant heat was presented to the midplantar region of the hind paw through the floor of the glass platform. Stimulation was terminated upon paw withdrawal or after 40 s to prevent tissue damage. Paw withdrawal latencies are reported as the mean of duplicate determinations averaged across paws.

Baseline mechanical withdrawal thresholds and thermal paw withdrawal latencies were assessed prior to pharmacological manipulations. Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds were re-assessed 15 min following injection of drug or vehicle. Thermal paw withdrawal latencies were measured at 30, 60 and 120 minutes post-injection to assess the time course of CB2 agonist actions.

Antinociception to thermal (in the Hargreaves test) and mechanical (electrovonfrey) stimulation was evaluated in otherwise naive rats. Separate groups of animals received either racemic (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.; n = 8) [data shown in (Rahn et al., 2010)], AM1710 (0.1, 0.33, 1, 5 and 10 mg/kg i.p.; n = 8 per group), or DMSO (n = 19). To determine pharmacological specificity, SR144528 (6 mg/kg) or SR14176 (6 mg/kg i.p.) was administered 20 min prior to AM1710 (0.1 or 5 mg/kg; n = 8–9 per group). SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p., n = 8 per group) or SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.; n = 8) did not alter basal nociceptive thresholds to mechanical or thermal stimulation at these doses (Rahn et al., 2010). Thermal withdrawal latencies were re-determined, in duplicate for each paw, at 30, 60 and 120 min following injection.

2.5.2. Tetrad Testing

2.5.2a. Tail Flick/Rectal Temperature

A modified tetrad profile was performed to assess CNS side-effects. Tail flick latency and rectal temperature were assessed in the same animals. Tail flick (D’Amour and Smith, 1941) was assessed using a commercially available tail flick unit (IITC model 336; Woodland Hills, CA). Animals were placed in restraint tubes (IITC model 81; Woodland Hills, CA) and allowed 10 min to habituate prior to testing. Radiant heat was presented to the tail and the latency for the animal to withdraw its tail from the heat source was recorded. Stimulation was terminated when the animal withdrew its tail from the radiant heat source. A cut-off latency of 10 s was employed to prevent tissue damage. Baseline tail flick latencies are reported as the mean of six tail flick latencies. Tail flick latencies were re-determined at 30, 60, and 120 min post-injection and are reported at each time point as the mean of four tail flick latencies.

Rectal temperature was assessed using a commercially available rectal probe (Physitemp RET-2 rectal probe for rats; Clifton, NJ) and meter (Physitemp Model BAT-12R; Clifton, NJ). Following assessment of baseline tail flick latencies, rectal probes, lubricated with Vaseline®, were inserted to a depth of approximately 2.4 cm. Probes were then connected to the meter and body temperature was recorded. Baseline rectal temperature is reported as the mean of four measurements. Rectal temperatures were then determined in duplicate at 35, 65, and 125 min post-injection and are reported at each time point as the mean of duplicate determinations.

To evaluate centrally-mediated antinociception (assessed in the tail flick test) and hypothermia, separate groups of animals received either (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.; n = 7), AM1710 (0.1, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p.; n = 6 per group), DMSO (n = 7), the reference cannabinoid CB1/CB2 agonist WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.; n = 7) or the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.) 20 min prior to the administration of WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.; n = 6).

2.5.2b. Activity Meter/Rota-rod

Locomotor activity and motor ataxia were assessed in the same animals. Distance traveled in an activity meter was assessed by placing rats individually in the center of a polycarbonate activity monitor chamber (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) measuring 44.5 × 44 × 34 cm housed in a darkened, quiet room. A 25-watt bulb positioned one meter over the chamber provided illumination. Activity was automatically measured by computerized analysis of photobeam interrupts (Med Associates). Total distance (cm) traveled in the arena was used for data analysis. Animals were placed in the activity meter at 20 min post-injection and remained undisturbed in this chamber for 15 min. Following activity meter testing, animals were tested on the rota-rod.

Motor ataxia was assessed using a commercially available rota-rod unit (IITC model 755 RotoRod; Woodland Hills, CA). Animals were required to walk against the motion of a rotating drum increasing in speed from 4 revolutions per min (rpm) to 40 rpm, similar to that described by Fox and colleagues (2001). The descent latency (i.e. the time for an animal to fall off the rotating drum) was recorded (sec). No cut-off latency was employed in the rota-rod test to ensure that detection of subthreshold motor ataxia would not be masked by the cut-off latency employed (Taylor et al., 2003). Rota-rod training took place on the two days prior to the test day. Animals were given a minimum of three practice trials on both training days. Practice trials terminated when the animals fell off of the rotating drum. Training trials in which the animal failed to remain on the rotating drum for a minimum of 10 sec were re-run. On the test day, reliability testing was performed. Animals that could not remain on the rotating drum for 30 seconds in two separate trials failed to meet the criteria (approximately 20%) and were dropped from the experiment. Rota-rod descent latency was calculated after drug administration at 35, 65, and 125 min post-injection. Rota-rod latencies at each time point post-injection are reported as the mean of two separate rota-rod descent latencies.

To evaluate possible centrally mediated side-effects of hypoactivity and motor ataxia, animals received either the DMSO vehicle (n = 8), (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.; n = 6), AM1710 (0.1, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p.; n = 8–9 per group) or WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.; n = 7). To assess pharmacological specificity, a separate group was pre-treated with SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.) 20 min prior to WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.; n = 7).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Percent change in paw withdrawal latencies from baseline was calculated with the following formula: ((Post-drug paw withdrawal latency – baseline)/baseline) * 100. Antinociception in the tail flick test was expressed as the percent of maximum possible effect (% MPE), using the formula:

Change in temperature (Δ °C) was calculated with the following formula: (Post-drug temperature – mean baseline temperature). Z-scores were calculated for tetrad animals tested in the activity meter and rota-rod. Three animals with Z-scores of ± 2 standard deviations from the mean in either test were excluded from analysis.

All data was analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures, one-way ANOVA or planned comparison Student t-tests, as appropriate. SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Incorporated, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to all repeated factors. Post hoc comparisons between control groups and other experimental groups were performed using the Dunnett test. Post-hoc comparisons between different experimental groups were also performed to assess dose-response relationships and pharmacological specificity using the Tukey test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Results of in vitro screen for target selectivity

AM1710 demonstrated 17-fold selectivity for mCB2 (Ki = 17+/−10 nM) compared to rCB1 (Ki = 282 +/−91 nM; data are the average +/− standard deviation of five separate experiments run in triplicate). An in vitro screen was also used to assess the target selectivity of AM1710 for CB2 receptors. The Novascreen failed to identify off-target activity of AM1710 at 62 different targets including neurotransmitter-related G-protein coupled receptors, steroids, ion channels, second messenger-related prostaglandins, growth factors/hormones, brain/gut peptides and enzymes (Supplementary File). In the NovaScreen, AM1710 did not inhibit [3H]CP55,940 binding to hCB1 at 100 nM, but exhibited 50% inhibition of binding at10,000 nM. In a fluorescence assay, AM1710, in concentrations up to 100 μM, also failed to inhibit activity of fatty-acid amide hydrolase and monoacylglycerol lipase, enzymes implicated in endocannabinoid deactivation (data not shown).

3.2. Brain Barrier Penetration of AM1710

An in vivo screen was used to determine the ability of AM1710 to cross the blood brain barrier using intravenously administered doses of 1 mg/kg. The amount of AM1710 found in the unperfused brain tissue was 0.066%/g of the injected dose, while plasma contained 0.000086%/mL (Table 1). AM1710 has a low brain penetration expected, compared to other cannabilactones screened in this class (B/P ratio range = 0.03–1.3 mL/g; unpublished results).

Table 1.

Brain barrier penetration of AM1710 (1 mg/kg i.v.)

| Plasma concentration | 75.25 ± 12.29 ng/mL |

| Brain concentration | 17.38 ± 2.63 ng/g |

| Brain-to-plasma ratio | 0.23 mL/g |

Data are mean ± standard deviation. Plasma and brain samples were removed 15 min post-injection, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until processing and analysis by LC-MS/MS.

3.3. Behavioral Results

3.3.1. General Results

Thermal paw withdrawal latencies and mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds did not differ between right or left paws for any group. Therefore, withdrawal thresholds in all studies are presented as the mean of duplicate measurements, averaged across paws. Baseline responses (i.e. thermal paw withdrawal latencies or mechanical withdrawal thresholds) were also similar between groups prior to administration of drug or vehicle. Baseline paw withdrawal latencies did not differ between groups in any study; therefore, baselines in the log dose response plot (Fig 2) were averaged across all doses of the same drug for statistical analyses. Moreover, paw withdrawal latencies and thresholds did not differ based upon the order of thermal and mechanical testing at baseline; therefore, the two vehicle groups are combined for all studies presented.

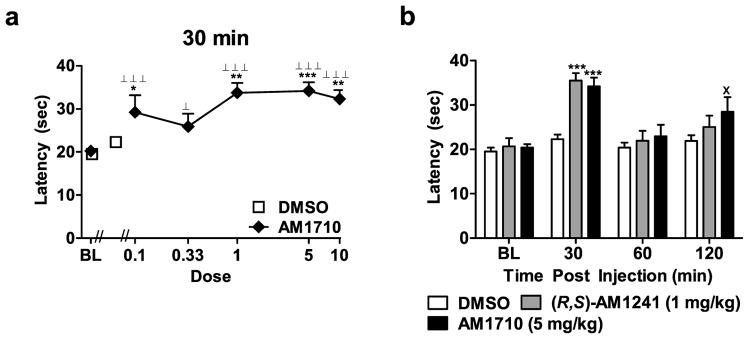

Figure 2.

(a) Log dose response for AM1710-induced antinociception in the plantar test. (b) Time course of antinociceptive effects observed following administration of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) in comparison with (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) (n = 8 previously published in Rahn et al., 2010). Withdrawal latencies to thermal stimulation in the plantar test are shown. BL denotes baseline paw withdrawal latencies observed prior to agonist or vehicle injection. Doses are in mg/kg. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. DMSO control condition, ⊥P < 0.05, ⊥ ⊥ ⊥P < 0.001 vs. baseline (ANOVA; Dunnett and Tukey post hoc tests), × < 0.05 vs. DMSO control condition (Student t-test). N = 8–19 per group.

One animal that received AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) died approximately 45 min post-injection and was excluded from all analyses. The animal likely died from a misplaced injection as no other animals receiving AM1710 at this, or any other dose tested, showed similar effects or was moribund. Within the tetrad (activity meter/rota-rod), two animals from the WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) group, and one animal from the AM1710 (10 mg/kg i.p.) group were excluded from all analyses based on Z-scores.

3.3.2. The Cannabilactone AM1710 Produces Antinociception to Thermal but not Mechanical Stimulation of the Hind Paw

3.3.2a. Responses to Mechanical Stimulation

AM1710 (1 mg/kg i.p), but not other doses of the cannabilactone, produced modest but reliable increases in mechanical withdrawal thresholds relative to corresponding pre-injection thresholds (P < 0.05 planned comparison t-test; Table 1). However, this same dose did not alter post-injection thresholds relative to the vehicle condition. Moreover, antagonist pre-treatment did not alter paw withdrawal thresholds, relative to baseline (Table 2). Paw withdrawal thresholds were not altered by (R,S)-AM1241 (previously published; Rahn et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Paw withdrawal thresholds (g) to punctuate mechanical stimulation in animals that received the cannabilactone AM1710

| Group | Pre-injection | Post-Injection |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO | 67.8 ± 3.6 | 71.0 ± 4.8 |

| AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg) | 79.1 ± 4.2 | 74.0 ± 5.9 |

| AM1710 (0.33 mg/kg) | 66.1 ± 3.1 | 71.4 ± 4.6 |

| AM1710 (1 mg/kg) | 63.9 ± 3.6 | 73.3 ± 2.3+ |

| AM1710 (5 mg/kg) | 70.2 ± 3.7 | 64.7 ± 5.3 |

| AM1710 (10 mg/kg) | 63.9 ± 3.3 | 68.8 ± 5.5 |

| AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg) | 79.1 ± 4.2 | 74.0 ± 5.9 |

| AM1710 (0.1) + SR2 (6) | 73.7 ± 5.4 | 71.6 ± 4.7 |

| AM1710 (0.1) + SR1 (6) | 68.0 ± 4.2 | 69.3 ± 4.7 |

| AM1710 (5 mg/kg) | 70.2 ± 3.7 | 64.7 ± 5.3 |

| AM1710 (5) + SR 2 (6) | 81.4 ± 3.7 | 72.3 ± 3.1 |

| AM1710 (5) + SR1 (6) | 70.5 ± 5.7 | 64.1 ± 8.5 |

| SR141716 (6 mg/kg) | 63.3 ± 5.5 | 75.6 ± 5.7 |

| SR144528 (6 mg/kg) | 70.9 ± 5.1 | 62.8 ± 5.8 |

Data are mean ± s.e.mean. Doses are in mg/kg. SR1 = SR141716; SR2 = SR144528. Statistical comparisons were performed on groups separated by line divisions.

P < 0.05 vs. same group pre-injection threshold (Student t-test).

3.3.2b. Responses to Thermal Stimulation in the Plantar Test

The cannabilactone AM1710 (0.1, 1, 5 and 10 mg/kg i.p.) increased thermal paw withdrawal latencies relative to vehicle at 30 min post-drug (F5,55 = 5.859, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 for each comparison). All doses of AM1710 also increased paw withdrawal latencies relative to baseline measurements at this time point (F5,78 = 17.311, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 for each comparison; Fig 2a). Paw withdrawal latencies were maximally increased in groups receiving AM1710 (0.1, 0.33, 1, 5 and 10 mg/kg i.p.) at 30 min post-injection; percent increases ranged from 31.5 to 64.4%.

3.3.3. Comparison of Antinociceptive Effects Induced by AM1710 and (R,S)-AM1241

The dose of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) that produced the greatest antinociception at 30 minutes post-injection (81.5% and 64.4% increase in paw withdrawal latencies, respectively) was compared with the maximally effective dose of (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) identified previously in the same test (data from Rahn et al., 2010) and compared across the entire testing time course (F6,72 = 4.138, P < 0.01, Fig 2b). Although both drugs produced equivalent antinociception at 30 min post-injection relative to the vehicle control (F2,24 = 9.60, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 for each comparison), the antinociceptive effects of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) outlasted those produced by (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) (Fig. 2b).

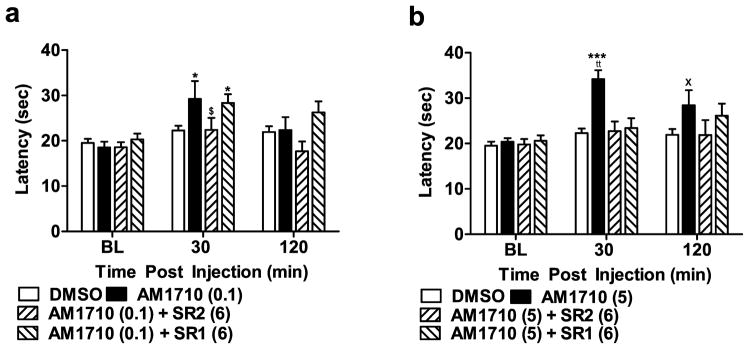

3.3.4. Pharmacological Specificity

Antinociception produced by the lowest efficacious dose of the cannabilactone AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) was selectively blocked by the CB2 antagonist SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.) (F3,41 = 3.255, P < 0.05; Fig 3a) but not by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.). AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) produced antinociception relative to the vehicle condition at 30 min (P < 0.05 for comparison) but not at 120 min post-injection (P > 0.08). By contrast, antinociceptive effects of a higher dose of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) were blocked (F3,40 = 7.450, P < 0.001; Fig 3b) by both SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.) and SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.) at 30 min post-injection. Antinociceptive effects of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) persisted at 120 minutes post-injection (P < 0.05, planned comparison t-test), suggesting that the duration of action of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) outlasted that of AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.). Paw withdrawal latencies were similar in groups receiving vehicle or pre-treatment with either antagonist at 120 minutes post-injection.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological specificity of antinociceptive effects of AM1710 in the plantar test. (a) Antinociceptive effects of AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) were blocked by the CB2 antagonist (SR2; 6 mg/kg i.p.), but not the CB1 antagonist (SR1; 6 mg/kg i.p.) (b) Antinociceptive effects of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) were blocked by either SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.) or SR144528 (6 mg/kg i.p.). *P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001 vs. DMSO control, ttP < 0.01 vs. all drug groups, (ANOVA; Dunnett and Tukey post hoc tests). $P < 0.05 vs. AM1710 (0.1) + SR1 (6), ×P < 0.05 vs. DMSO control (Student t-test). N = 8–19 per group.

3.3.5. Assessment of CNS Side-effects: Antinociception in the Tail Flick Test and Hypothermia

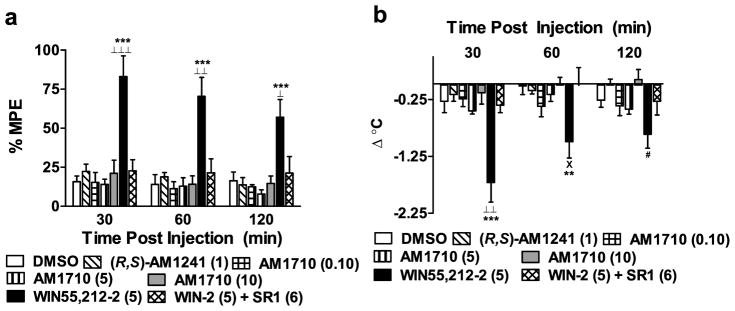

WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p) produced characteristic CB1-mediated antinociception in the tail flick test that was not produced by either AM1710 or (R,S)-AM1241. Tail flick latencies were elevated in WIN55, 212-2-treated groups relative to vehicle, (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p), and all doses of AM1710 (F6,38 = 10.505, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 for each comparison; Fig 4a) at all time points post-injection (30 min: F6,38 = 11.298, P < 0.001; P < 0.001 for each comparison; 60 min: F6,38 = 8.196, P < 0.001; P < 0.01 for each comparison; 120 min: F6,38 = 6.028, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 for each comparison). The CB1 antagonist, SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p), blocked the antinociceptive effects of WIN55,212-2 in the tail flick test across the entire observation interval (P < 0.05 for each comparison), consistent with mediation by CB1. By contrast, AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) and (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p) failed to alter tail flick latencies at any post-injection time point relative to the DMSO vehicle condition (P > 0.60 for each comparison).

Figure 4.

(a) Effects of cannabilactone and aminoalkylindole cannabinoid agonists on tail flick antinociception and hypothermia. WIN55,212-2 (WIN-2; 5 mg/kg i.p.) produced CB1-mediated antinociception in the tail flick test. This effect was blocked by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (SR1; 6 mg/kg i.p.). Neither (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) nor AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) produced antinociception in the tail flick test. (b) WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) decreased rectal temperature relative to baseline through a CB1 mechanism; this effect was blocked by SR141716 (SR1; 6 mg/kg i.p.). Neither (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) nor AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) altered rectal temperature. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. DMSO control condition, ⊥P < 0.05, ⊥⊥P < 0.01, ⊥⊥ ⊥P < 0.001 vs. all drug conditions, ×P < 0.05 vs. AM1710 (10 mg/kg i.p.), WIN-2 + SR1, and (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.), #P < 0.05 vs. AM1710 (10 mg/kg i.p.) (ANOVA; Dunnett and Tukey post hoc tests). N = 6–7 per group.

WIN55,212-2 also produced a characteristic CB1-mediated hypothermic effect that was not produced by the cannabilactone AM1710 or the aminoalkylindole (R,S)-AM1241. WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p) decreased rectal temperature relative to vehicle, (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p) and all doses of AM1710 (F6,38 = 5.207, P < 0.01; P < 0.05 for each comparison; Fig 4b) at 35 minutes post-injection (F6,38 = 8.353, P < 0.001; P < 0.01 for each comparison). A hypothermic effect of WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p) was still apparent, relative to vehicle, at 65 minutes (F6,38 = 3.576, P < 0.01, P < 0.01 for relevant comparison; Fig 4b) but not 125 minutes (P > 0.13) post-injection. The hypothermic effects of WIN55,212-2 were completely blocked by SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p; P < 0.05 for each comparison), consistent with mediation by CB1. By contrast, AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg) and (R,S)-AM1241 did not alter rectal temperature relative to the vehicle condition at any time point (P > 0.32 for each comparison).

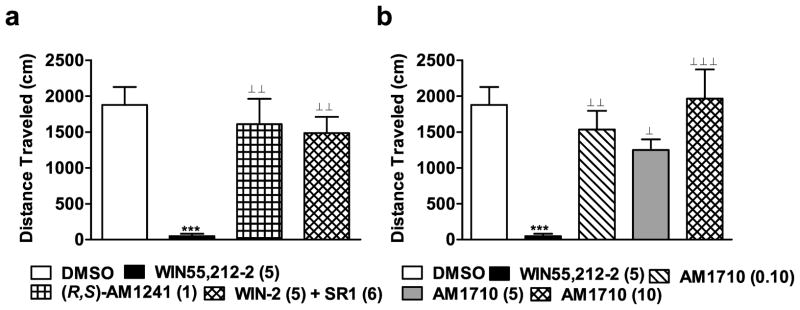

3.3.6. Assessment of CNS Side-effects: Hypoactivity and Motor Ataxia

WIN55,212-2 produced a characteristic CB1-mediated hypoactivity that was not produced by antinociceptive doses of (R,S)-AM1241 or AM1710. WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) decreased distance traveled in the activity meter relative to all other groups (F3,24 = 12.404, P < 0.001; P < 0.01 for each comparison in Fig 5a; F4,33 = 9.154, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 for each comparison in Fig 5b). As expected, WIN55,212-2-induced hypoactivity was blocked by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (6 mg/kg i.p.; P < 0.01 for comparison; Fig. 5a). By contrast, (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.; Fig. 5a) did not alter locomotor activity relative to the vehicle condition (P > 0.42). AM1710 (0.1, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p.) did not reliably inhibit locomotor activity relative to the vehicle condition at any dose (P > 0.11; Fig 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Effects of cannabilactone and aminoalkylindole cannabinoid agonists on locomotor activity. WIN55,212-2 (WIN-2; 5 mg/kg i.p.) reduced total distance traveled (cm) through a CB1 mechanism. This effect was blocked by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 (SR1; 6 mg/kg i.p.). (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter locomotor activity. (b) AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter locomotor activity. ***P < 0.001 vs. DMSO control condition, ⊥P < 0.05, ⊥ ⊥P < 0.01, ⊥⊥ ⊥P < 0.001 vs. WIN55,212 (5 mg/kg i.p.), (ANOVA; Dunnett and Tukey post hoc tests). N = 6–8 per group.

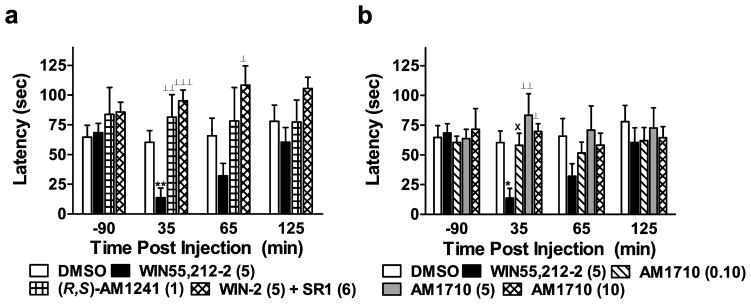

WIN55,212-2 produced a characteristic CB1-mediated motor ataxia in the rota-rod test (F3,24 = 5.431, P < 0.01; Fig 6a). These effects were not observed with the cannabilactone AM1710 or the aminoalkylindole (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.). WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) impaired the ability of rats to walk on a rotating drum relative to either vehicle or (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) at 35 minutes post-injection (F3,24 = 9.422, P < 0.001; P < 0.01 for each comparison; Fig 6a). As expected, WIN55,212-2-induced motor ataxia was completely blocked by SR141716 at this time point (P < 0.001 for relevant comparison).

Figure 6.

(a) Effects of cannabilactone and aminoalkylindole cannabinoid agonists on motor ataxia. WIN55,212-2 (WIN-2; 5 mg/kg i.p.) produced CB1-mediated motor ataxia, manifested as a decrease in descent latency (sec) in the rota-rod test. This effect was blocked by SR141716 (SR1; 6 mg/kg i.p.). Neither (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) nor (b) AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) altered rota-rod latency relative to the vehicle condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. DMSO control condition, ⊥P < 0.05, ⊥⊥P < 0.01, ⊥ ⊥ ⊥P < 0.001 vs. WIN55,212 (5 mg/kg i.p.) (ANOVA; Dunnett and Tukey post hoc tests). ×P < 0.05 vs. WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) (Student t-test). N = 6–8 per group.

WIN55,212-2 also produced motor ataxia relative to the cannabilactone AM1710 (5 and 10 mg/kg i.p.) (F4,33 = 4.790, P < 0.01; P < 0.05 for relevant comparison; Fig 6b) at 35 min post-injection. WIN55,212-2 (5 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter rota-rod latencies relative to vehicle at subsequent time points (65 min: P > 0.14 and 125 min: P > 0.36 for Fig 6a,b), suggesting that the antinociceptive and hypothermic effects of WIN55,212-2 outlast the motor ataxic effects of the same dose.

(R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.) and AM1710 (0.1, 5, and 10 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter rota-rod descent latencies relative to vehicle at any time point (P > 0.46) (Fig. 6a,b). Rota-rod latencies were lower in groups receiving WIN55,212-2 relative to groups receiving AM1710 (P < 0.05 for each comparison, Tukey post hocs and planned comparison t-test).

4. Discussion

The present studies demonstrate that the cannabilactone CB2 agonist AM1710 is highly specific for the CB2 receptor as previously suggested by an in vitro screen for target selectivity (Khanolkar et al., 2007). AM1710 was previously validated to be 14-fold more selective at rat compared to human CB2 receptors (Mukherjee et al., 2004). In a species comparison of binding profiles, AM1710 exhibited Kis of 28 nM and 2 nM, respectively, for inhibiting [3H]CP55,940 binding to HEK cells stably expressing human and rat CB2 receptors respectively (Mukherjee et al., 2004). Here we additionally show that AM1710 has negligible affinity for an additional 62 targets investigated in the NovaScreen ‘side-effect’ profile assay (Caliper Life Sciences, Hanover, MD, USA; see Supplementary Data) including TRPV1 and did not alter activity of enzymes catalyzing endocannabinoid hydrolysis (FAAH, MGL), further validating the specificity of the compound for CB2 receptors. These observations are consistent with the results of behavioral studies documenting the absence of centrally-mediated side-effects associated with activation of CB1 receptors. Moreover, the compound exhibited limited blood brain barrier penetration, compared to other compounds of its class.

4.1. AM1710-induced Antinociception

AM1710 produced antinociception in the plantar test in the absence of unwanted CNS side-effects. The most striking observation of our study was that doses 100-fold higher than the lowest maximally effective antinociceptive dose showed no signs of CNS activity in the tetrad (i.e. tail flick antinociception, body temperature, rotarod, locomotor activity). The lack of dose dependence observed for AM1710 suggests that this compound exhibits high potency for producing antinociception. There may also be a limit in the magnitude of antinociception that can be produced in the plantar test following CB2 agonist administration, at least in naive animals.

AM1710 failed to produce antinociception to punctate mechanical stimulation relative to vehicle treatment. Withdrawal responses may occur because the mechanical stimulation is noxious or because it represents an annoying or unpleasant touch sensation to the animal. Electrophysiological studies provide insight into the classes of primary afferents activated by mechanical stimulation of the plantar paw skin. Following stimulation of the plantar skin with calibrated von Frey filaments, mechanical thresholds for activation of Aδ-nociceptors averaged 37.77 mN (i.e. approximately 3.85 g), with a range of 14-100 mN (i.e. approximately 1.4–10.2 g), whereas mechanical thresholds for activation of C-nociceptors averaged 80.24 mN (i.e. 8.19 g), with a range of 14–294 mN (i.e. approximately 1.4–29.9 g) (Leem et al., 1993a). In our study, animals withdrew from the electrovonfrey at thresholds exceeding these forces (see Table 2), suggesting that electrovonfrey stimulation likely resulted in nocicceptor activation. It is nonetheless important to note that methodological differences exist between the present study and the study by Leem et al. (1993a). The electrovonfrey used in our study offers a significant advantage over testing with traditional von Frey filaments; the area of skin stimulated with the electrovonfrey is constant regardless of the amount of force applied, eliminating the confound that is introduced when manual filaments of increasing diameters are applied to the hindpaw in the traditional method. The electrovonfrey also stimulates a larger surface area (0.8 mm for all forces applied) than most of the traditionally used von Frey filaments (which range from 0.178 – 0.813 mm in diameter for filaments applying published forces ranging from 0.407 to 75.856 g, respectively). Nonetheless, the smaller surface area of skin stimulated by mechanical versus thermal testing may also contribute to our observation of modality-specific antinociceptive effects. Differential nociceptor activation associated with mechanical versus heat stimulation may also contribute to these findings (Leem et al., 1993b). The heat stimulus may activate a greater number of nociceptors than the electrovonfrey given the differences in skin surface areas stimulated by the thermal and mechanical probes. Cannabilactones have, however, been shown to suppress paclitaxel-evoked mechanical allodynia and normalize mechanical withdrawal thresholds (Rahn et al., 2008) at doses that do not produce antinociception to the same stimulus modality in otherwise naive animals.

AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) exhibited a similar maximal effect and a longer duration of action than the aminoalkylindole CB2 agonist (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.). In previous work, both AM1714 and AM1710 produced thermal antinociception when administered locally (i.paw) (Khanolkar et al., 2007). However, this is the first study to demonstrate antinociceptive effects of a cannabilactone compound following systemic administration in naive animals.

4.2. Pharmacological Specificity of AM1710-induced Antinociception

Although (R,S)-AM1241-induced antinociception was selectively blocked by the CB2 antagonist SR144528, but not by the CB1 antagonist SR141716 when tested under identical conditions (Rahn et al., 2010), the in vivo pharmacological specificity of systemically administered AM1710 has proven more difficult to interpret. A low dose of AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.), which produced antinociception comparable to that of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) at 30 minutes (time point of maximal antinociception), showed no evidence for mediation by CB1; antinociception produced by AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) was insensitive to blockade by SR141716. By contrast, pre-treatment with either SR144528 or SR141716 completely blocked the antinociceptive effects of a higher dose of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.). The in vivo pharmacology of AM1710 is more complex than would be expected from the in vitro binding affinities (Khanolkar et al., 2007) which demonstrated that cannabilactones (AM1714 and AM1710) bind with only low affinity to CB1 receptors. More work is necessary to determine whether differences in the bioactive transformations of the cannabilactones contribute to the in vivo pharmacology of these compounds. Thus, it is potentially noteworthy that AM1710 produced antinociception at 30 and 120 min post-injection, but not at 60 min post-injection. More work is necessary to identify metabolites of AM1710 and determine whether they are biologically active and brain permeable.

A CB1 component was not observed previously in groups that received the aminoalkylindole (R,S)-AM1241 and the same dose of the CB1 antagonist and tested under identical conditions (Rahn et al., 2010). Locally administered AM1714 also produces thermal antinociception in the plantar test that was blocked by the CB2-selective antagonist AM630 but not by the CB1-selective antagonist AM251 (Khanolkar et al., 2007). Thus, cannabilactone-induced antinociception is mediated, at least in part, by peripheral sites of action. No evidence for a CB1 component in AM1710-induced antinociception was observed following administration of a lower dose of AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.), which nonetheless produced maximal antinociception (at 30 minutes) in the plantar test. Thus, increasing the dose did not further increase the antinociceptive effects of AM1710 but could presumably increase the amount of AM1710 available for metabolic transformation and/or produce a low percentage of CB1 receptor occupancy.

Animals that received AM1710 did not exhibit cardinal signs of CB1 receptor activation such as antinociception in the tail flick test, hypothermia, hypoactivity, or motor ataxia. Thus, any CB1 activity produced by systemically administered AM1710 is likely to be peripheral CB1 activity. It is important to note that the blood brain barrier penetration data indicated AM1710 does enter the brain, albeit at low levels. Consequently, AM1710 might show high antinociceptive efficacy in neuropathic pain states where, due to its blood brain barrier penetration, it could modulate upregulated CB2 receptors in the CNS (Beltramo et al., 2006; Wotherspoon et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2003) without crossing the threshold for CB1 receptor activation that produces hallmark side-effects. More work is necessary to evaluate this and other compounds from the cannabilactone class in states of induced neuropathic pain. For example, systemic cannabilactone administration suppresses chemotherapy-induced neuropathy through a CB2-specific mechanism; the anti-allodynic effects of AM1714, observed in response to tactile stimulation, were blocked by SR144528, but not by SR141716. In fact, animals receiving SR141716 prior to administration of AM1714 showed enhanced antinociception (Rahn et al., 2008). Thus, pharmacological specificity of these agonists may differ based upon whether or not these compounds are evaluated systemically or locally in the paw or under conditions (normal vs. neuropathic) in which CB2 or CB1 receptors may be upregulated.

Off-target effects could potentially contribute to the blockade of cannabilactone-induced antinociception produced by SR141716 in our study. However, the drug screens performed indicated that AM1710 does not significantly bind to common off-target receptors and does not inhibit activity of enzymes (i.e. FAAH, MGL) implicated in endocannabinoid deactivation. Additionally, the same dose of SR141716 (6 mg/kg) which blocked the antinociceptive effects of AM1710 (5 mg/kg i.p.) did not block antinociception produced by either a lower dose of AM1710 (0.1 mg/kg i.p.) or (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.). It is, however, important to note that anxiolytic effects of SR141716 (Haller et al., 2002; Rodgers et al., 2003; but see Thiemann et al., 2009) are observed in CB1−/− knockout mice (Uriguen et al., 2004), suggesting that they may be mediated through a “non-CB1” site. SR141716 also binds TRPV1 receptors at micromolar concentrations (De Petrocellis et al., 2001). However, a role for TRPV1 in cannabilactone actions is unlikely because activation of TRPV1 produces hypothermia in vivo (Miller et al., 1982) and our studies demonstrate that AM1710 does not bind to TRPV1 or alter body temperature.

4.3. Central Nervous System Side-effect Profile of AM1710

This is the first study to assess CNS side-effects in the tetrad produced by the cannabilactone AM1710. Previously, AM1714 (3.3 mg/kg i.p.) was tested in the rota-rod where it showed no activity relative to baseline measurements (Khanolkar et al., 2007). No centrally-mediated side-effects were observed in animals that received AM1710 (0.1, 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p.) or (R,S)-AM1241 (1 mg/kg i.p.). Similar results have been reported for (R,S)-AM1241 in a tetrad which did not include tail flick (Malan et al., 2001). However, higher doses of (R,S)-AM1241 (10 mg/kg i.p.) produce modest increases in tail flick latencies in mice (Ibrahim et al., 2006), whereas similar doses of AM1710 in rats (10 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter tail-flick latency or produce any sign of CNS side-effects in the tetrad.

4.4. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the cannabilactone AM1710, like the aminoalkylindole (R,S)-AM1241, produces antinociception in the plantar test without producing cardinal signs of CB1 receptor activation. The plantar test may be more sensitive than the tail flick test to detection of CB2-mediated and peripherally-mediated antinociceptive effects (see Guindon and Hohmann, 2008 for review). Our studies suggest that cannabilactones such as AM1710 produce cannabinoid receptor-mediated antinociception at doses that do not produce CNS side-effects typical of CB1 receptor activation. These observations suggest that the cannabilactone compound, AM1710, is representative of a promising class of novel cannabinoid analgesics which lack unwanted CNS side-effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mahmoud Nasr and Subramanian K. Vadivel for their work on the enzyme assays. We are very grateful to National Institutes of Drug Abuse for funding the multiple target screening of AM1710 carried out by NovaScreen Biosciences Corporation. This work was supported by DA021644, DA028200 (AGH) and DA9158, DA3801 (AM). EJR was supported by an APF Graduate Fellowship, a Psi Chi Graduate Research Grant, a Sigma Xi Grant-in-Aid of Research and an ARCS Foundation Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Statement of Conflict of Interests. There is a conflict of interest. A.M. serves as a consultant for MAK Scientific.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anand P, Whiteside G, Fowler CJ, Hohmann AG. Targeting CB(2) receptors and the endocannabinoid system for the treatment of pain. Brain research reviews. 2009;60:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Bernardini N, Bertorelli R, Campanella M, Nicolussi E, Fredduzzi S, et al. CB2 receptor-mediated antihyperalgesia: possible direct involvement of neural mechanisms. The European journal of neuroscience. 2006;23:1530–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochemical pharmacology. 1973;22:3099–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amour FE, Smith DL. A Method for Determining Loss of Pain Sensation. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1941;72:74–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T, Maccarrone M, Davis JB, Finazzi-Agro A, Di Marzo V. The activity of anandamide at vanilloid VR1 receptors requires facilitated transport across the cell membrane and is limited by intracellular metabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:12856–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon J, Hohmann AG. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: a therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:319–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller J, Bakos N, Szirmay M, Ledent C, Freund TF. The effects of genetic and pharmacological blockade of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor on anxiety. The European journal of neuroscience. 2002;16:1395–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus L, Breuer A, Tchilibon S, Shiloah S, Goldenberg D, Horowitz M, et al. HU-308: a specific agonist for CB(2), a peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14228–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Farthing JN, Zvonok AM, Makriyannis A. Selective activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptors suppresses hyperalgesia evoked by intradermal capsaicin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:446–53. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Porreca F, Lai J, Albrecht PJ, Rice FL, Khodorova A, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor activation produces antinociception by stimulating peripheral release of endogenous opioids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3093–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409888102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Rude ML, Stagg NJ, Mata HP, Lai J, Vanderah TW, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor mediation of antinociception. Pain. 2006;122:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanolkar AD, Lu D, Ibrahim M, Duclos RI, Jr, Thakur GA, Malan TP, Jr, et al. Cannabilactones: a novel class of CB2 selective agonists with peripheral analgesic activity. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6493–500. doi: 10.1021/jm070441u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R, Liu Q, Fan P, Lin S, Fernando SR, McCallion D, et al. Structure-activity relationships of pyrazole derivatives as cannabinoid receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1999;42:769–76. doi: 10.1021/jm980363y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem JW, Willis WD, Chung JM. Cutaneous sensory receptors in the rat foot. J Neurophysiol. 1993a;69:1684–99. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leem JW, Willis WD, Weller SC, Chung JM. Differential activation and classification of cutaneous afferents in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1993b;70:2411–24. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malan TP, Jr, Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Liu Q, Mata HP, Vanderah T, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor-mediated peripheral antinociception. Pain. 2001;93:239–45. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BR, Compton DR, Thomas BF, Prescott WR, Little PJ, Razdan RK, et al. Behavioral, biochemical, and molecular modeling evaluations of cannabinoid analogs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:471–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MS, Brendel K, Buck SH, Burks TF. Dihydrocapsaicin-induced hypothermia and substance P depletion. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982;83:289–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Adams M, Whiteaker K, Daza A, Kage K, Cassar S, et al. Species comparison and pharmacological characterization of rat and human CB2 cannabinoid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;505:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Selective activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptors suppresses spinal Fos protein expression and pain behavior in a rat model of inflammation. Neuroscience. 2003;119:747–57. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patricelli MP, Lashuel HA, Giang DK, Kelly JW, Cravatt BF. Comparative characterization of a wild type and transmembrane domain-deleted fatty acid amide hydrolase: identification of the transmembrane domain as a site for oligomerization. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15177–87. doi: 10.1021/bi981733n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn EJ, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Activation of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception evoked by the chemotherapeutic agent vincristine in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:765–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn EJ, Zvonok AM, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Antinociceptive effects of racemic AM1241 and its chirally synthesized enantiomers: lack of dependence upon opioid receptor activation. Aaps J. 2010;12:147–57. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn EJ, Zvonok AM, Thakur GA, Khanolkar AD, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG. Selective activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception induced by treatment with the chemotherapeutic agent paclitaxel in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:584–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramarao MK, Murphy EA, Shen MW, Wang Y, Bushell KN, Huang N, et al. A fluorescence-based assay for fatty acid amide hydrolase compatible with high-throughput screening. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers RJ, Haller J, Halasz J, Mikics E. ‘One-trial sensitization’ to the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabinoid receptor antagonist SR141716A in the mouse elevated plus-maze. The European journal of neuroscience. 2003;17:1279–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosburg JE, Kinsey SG, Lichtman AH. Targeting fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) to treat pain and inflammation. AAPS J. 2009;11:39–44. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BK, Joshi C, Uppal H. Stimulation of dopamine D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens inhibits inflammatory pain. Brain Res. 2003;987:135–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur GA, Nikas SP, Li C, Makriyannis A. Structural requirements for cannabinoid receptor probes. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2005:209–46. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26573-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann G, Watt CA, Ledent C, Molleman A, Hasenohrl RU. Modulation of anxiety by acute blockade and genetic deletion of the CB(1) cannabinoid receptor in mice together with biogenic amine changes in the forebrain. Behavioural brain research. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uriguen L, Perez-Rial S, Ledent C, Palomo T, Manzanares J. Impaired action of anxiolytic drugs in mice deficient in cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:966–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Wood J, Pandarinathan L, Karanian DA, Bahr BA, Vouros P, et al. Quantitative method for the profiling of the endocannabinoid metabolome by LC-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS. Anal Chem. 2007;79:5582–93. doi: 10.1021/ac0624086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JT, Williams JS, Pandarinathan L, Courville A, Keplinger MR, Janero DR, et al. Comprehensive profiling of the human circulating endocannabinoid metabolome: clinical sampling and sample storage parameters. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1289–95. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JT, Williams JS, Pandarinathan L, Janero DR, Lammi-Keefe CJ, Makriyannis A. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid supplementation alters select physiological endocannabinoid-system metabolites in brain and plasma. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1416–23. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotherspoon G, Fox A, McIntyre P, Colley S, Bevan S, Winter J. Peripheral nerve injury induces cannabinoid receptor 2 protein expression in rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;135:235–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hoffert C, Vu HK, Groblewski T, Ahmad S, O’Donnell D. Induction of CB2 receptor expression in the rat spinal cord of neuropathic but not inflammatory chronic pain models. The European journal of neuroscience. 2003;17:2750–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109–10. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvonok N, Pandarinathan L, Williams J, Johnston M, Karageorgos I, Janero DR, et al. Covalent inhibitors of human monoacylglycerol lipase: ligand-assisted characterization of the catalytic site by mass spectrometry and mutational analysis. Chem Biol. 2008a;15:854–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvonok N, Williams J, Johnston M, Pandarinathan L, Janero DR, Li J, et al. Full mass spectrometric characterization of human monoacylglycerol lipase generated by large-scale expression and single-step purification. J Proteome Res. 2008b;7:2158–64. doi: 10.1021/pr700839z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.