Abstract

Genotyping of 74 Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates was performed at four different loci (vacA signal sequence and mid-region, insertion-deletion polymorphisms at the 3′ end of the cag pathogenicity island, and cagA). The predominant vacA alleles and insertion-deletion motifs suggest an ancestral relationship between Irish isolates and either specific East Asian or Northern European strains. In addition, fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism-PCR genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of 32 representative Irish H. pylori isolates and 22 isolates from four different continents demonstrated that the Irish H. pylori isolates examined were weakly clonal and showed some association with both European and Asian isolates. These three genotyping techniques show that Irish H. pylori isolates have distinctive features that may have evolved in this insular European population.

Helicobacter pylori displays genetic diversity between strains at a very high level (17). This diversity has been shown to occur at specific loci within H. pylori isolates (3, 4, 21, 23). The vacA gene, which encodes the vacuolating cytotoxin, is a polymorphic locus present in all H. pylori strains. While this gene contains conserved regions, sequence variations occur in the signal sequence and the mid-region of the gene as a mosaic structure (3). The signal sequence can be one of four allelic subtypes (s1a, s1b, s1c, and s2) (25) and the mid-region can be one of two allelic subtypes (m1 and m2) (3). There have been numerous reports correlating these vacA allelic types with particular gastric diseases (5, 20), e.g., the vacA s1 m1 genotype has been associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany (18).

The cagA gene (cytotoxin-associated gene) is another polymorphic locus that is thought to be a marker for virulence and is associated with increased severity of disease in some geographic regions (6). The 3′ end of the cag pathogenicity island (cag PAI) (the region between the 3′ end of the cagA gene and the 3′ end of the glutamate racemase gene [glr]) contains different motifs that have previously been used for studying relationships between H. pylori isolates from different geographic regions (14). To demonstrate geographic partitioning of H. pylori isolates, other studies have investigated sequences of putative virulence and housekeeping genes (1).

Although H. pylori is a panmictic organism (10), a study encompassing isolates from different regions of the world identified weakly clonal groupings for this bacterium (1). There have also been indications of nonrandom geographic distributions of H. pylori genotypes that may aid in the understanding of the evolution of H. pylori and its clinical consequences in different parts of the world (14, 24). The predominant vacA alleles have been shown to distinguish H. pylori isolates in different geographic regions (13, 15, 16, 19, 24).

Fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism (FAFLP) analysis is a genotyping technique that has been used to investigate outbreaks of infection by Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Neisseria meningitidis (7, 11, 12). FAFLP analysis generates a specific profile for each strain under examination. These profiles can be grouped together, resulting in generalized patterns. Recently, FAFLP was used to examine the geographic partitioning of H. pylori isolates [N. Ahmed, A. A. Khan, D. E. Berg, and C. M. Habibullah, abstract from the Int. Workshop on Campylobacter, Helicobacter and Related Organisms (CHRO), 2001, Freiburg, Germany, Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291(Suppl. 31):D-11, 2001].

For the present study, Irish H. pylori isolates were characterized by FAFLP and insertion-deletion analyses, along with vacA genotyping and cag gene status, and compared to isolates from other geographic regions, namely India, United Kingdom, Peru, Spain, Japan, and Africa.

Seventy-four clinical H. pylori isolates were examined that had been obtained from single antral gastric biopsies from patients experiencing peptic ulcer disease at the Meath-Adelaide and St. James's Hospitals in Dublin. Culture and storage of isolates were performed as described previously (8). Twenty-two H. pylori strains from six different geographic regions were also analyzed (six from India, five from Peru, five from the United Kingdom, four from Spain, one from Africa, and one from Japan). Genomic DNA preparations were provided by Douglas E. Berg and Asish Mukhopadhyay (Washington University Medical School, St. Louis, Mo.) from 16 non-Irish and non-Indian H. pylori strains originally obtained by Robert H. Gilman, Teresa Alarcon, Manuel Lopez Brea, and John Atherton. The Indian preparations were from the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (Hyderabad, India).

Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (8). The sequences of the oligonucleotides used as PCR primers and their corresponding PCR product sizes are listed in Table 1. The signal sequences and mid-regions of the vacA gene, the cagA gene, and the insertion-deletion motifs at the 3′ end of the cag PAI were amplified in separate reactions as reported previously (3, 14, 25). Negative controls for PCR included sterile distilled water and Escherichia coli DNA from strain XL1-Blue. The nucleotide sequences of representative vacA and cagA PCR products were determined to confirm their identities.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences of primers and PCR product sizes

| Amplified gene or DNA region | Primer | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | PCR product size (bp [type]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cagA | CAGAFa | GATAACAGGCAAGCTTTTGAGG | 349 |

| CAGARa | CTGCAAAAGATTGTTTGGCAGA | ||

| Signal sequence of vacA | VA1-Fb | ATGGAAATACAACAAACACAC | 259 (s1) |

| VA1-Rb | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | 286 (s2) | |

| Signal sequence sla of vacA | SS1-Fb | GTCAGCATCACACCGCAAC | 190 |

| VA1-Rb | CTGCTTGAATGCGCCAAAC | ||

| Mid-region of vacA | VAG-Fa | CAATCTGTCCAATCAAGCGAG | 570 (m1) |

| VAG-Ra | GCGTCTAAATAATTCCAAGG | 645 (m2) | |

| Extreme right end of the cag PAI | cagF4584c | GTTATTACAAAAGGTGGTTTCCAAAAATC | 1,200 (IV) |

| cagR5280c | GGTTGCACGCATTTTCCCTTAATC | 1,000 (IIIa) | |

| 1,000 (Ia) | |||

| 700 (IIIa) | |||

| 700 (II) | |||

| Type IV insertion-deletion motif specific | Xins.Rc | CGCTCTCTAATTGTTCTAGGA | 520 |

| cagF4584c | Same as above | ||

| Type II insertion-deletion motif specific | IS606-1692c | CTAACAATTTGCCATTATGCTGT | 400 |

| cagR5280c | Same as above | ||

| Type III insertion-deletion motif specific | fcn unkc | TGGATTAAATCTTAATGAATTATCG | 320 |

| cagR5280c | Same as above | ||

| Type I and IV insertion-deletion motif specific | cagF4856c | GCGATGAGAAGAATATCTTTAGCG | 350 (I) |

| cagR5280c | Same as above | 400 (IV) |

Of the 74 isolates examined, 69% were of vacA type s1a m2, 27% were of vacA type s1a m1, and 4% were of vacA type s2 m2 (Table 2). The most common signal sequence and mid-region alleles were s1a and m2, respectively, which is in accordance with previous studies of Irish H. pylori isolates (22). The frequency of the predominant vacA allele found in this study is similar to those found in Taiwan (82%) (16) and China (85%) (19). However, vacA alleles have been shown to differ in frequency and type among East Asian isolates (13, 16, 19), e.g., s1c is the predominant signal sequence allele among East Asian isolates (24). Thus, Irish H. pylori isolates share vacA similarities with isolates from specific countries within Eastern Asia. This may reflect particular adaptations of H. pylori to specific host populations (9, 24) rather than indicating geographic relationships.

TABLE 2.

vacA typing and cagA insertion-deletion motif analysis of 74 Irish H. pylori isolatesa

| vacA or insertion-deletion type | No (%) of strains |

|---|---|

| vacA types | |

| s1a | 71 (95.9) |

| s2 | 3 (4.1) |

| m1 | 20 (27) |

| m2 | 54 (73) |

| s1a m2 | 51 (68.9) |

| s1a m1 | 20 (27) |

| s2 m2 | 3 (4.1) |

| Insertion-deletion types | |

| Ia | 6 (9.5) |

| II | 31 (49.2) |

| IIIa | 3 (4.8) |

| IIIb | 1 (1.6) |

| IV | 22 (34.9) |

For insertion-deletion motif analysis, only 63 isolates were typeable.

All of the 74 Irish H. pylori isolates were found to contain the cagA gene. This does not agree with a previous Irish study (8), but as no asymptomatic patients were included in the present study, this may have influenced the present finding. Moreover, the cagA status of this collection was not known before the study commenced. Characterization of the 3′ end of the cag PAI has shown that eight different insertion-deletion motifs can be present (Ia, Ib, Ic, II, IIIa, IIIb, IV, and V) (14). These insertion-deletion motifs have been shown to be well suited to population-level surveys of H. pylori genotypes (14). Type I motifs predominate in isolates from Spanish and Peruvian populations but are less common in strains from Northern European populations. Type II motifs are mostly found among Japanese and Chinese strains, but are also common in Northern European strains. Type III motifs predominate among isolates from Indian populations. When insertion-deletion analysis was performed on the isolates, 63 (85%) yielded useable PCR products, 4 (5%) produced multiple PCR products (which made it impossible to determine the different motifs at this locus), and 7 (10%) did not yield PCR products under the test conditions used, despite repeated attempts. Five insertion-deletion motifs were detected. Of the 63 characterizable isolates, 31 (49%) were found to have type II motifs, 22 (35%) had type IV motifs, 6 (9%) had type Ia motifs, 3 (5%) had type IIIa motifs, and 1 (2%) had a type IIIb motif (Table 2). These findings suggest that Irish H. pylori isolates are similar to Northern European strains, as type II motifs are common in this region, but not to East Asian isolates, as the frequencies of occurrence are much higher (95%) (14). However, although type II motifs are common in Irish and Northern European isolates, type I motifs also have a high prevalence among Northern European strains, whereas Irish isolates show a high prevalence of type IV motifs. Interestingly, the only isolate yielding a type IV motif in a study of 500 strains was from England (14). A more extensive study of English strains by insertion-deletion analysis is required to clarify the frequency of occurrence of type IV motifs among isolates from different ethnic groups, including the Irish diaspora. Thus, this collection of Irish H. pylori isolates displays a rare insertion-deletion genotype that may be representative of an insular European population.

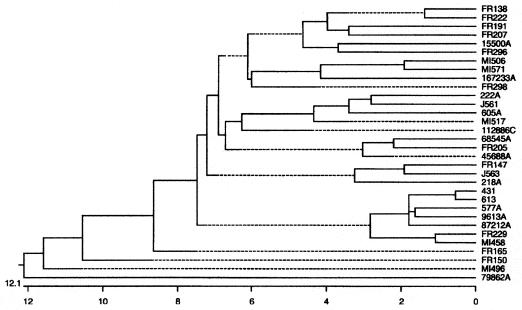

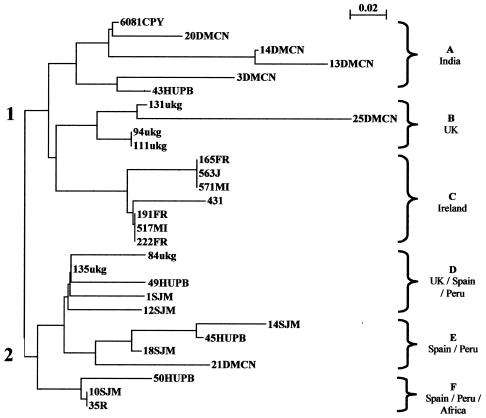

FAFLP-PCR was carried out as previously detailed (2). The fingerprints for each Irish isolate were generated by using three selective primers (EcoRI plus A, G, and C), and the fingerprints for each non-Irish isolate were generated by using one selective primer (EcoRI plus G). Amplified products were sized in base pairs within the user-defined categories of marker sizes. The presence or absence of amplicons within the categories was scored by a user-defined Genotyper macro. Allele scores (presence or absence of amplicons) were converted into a binary format (1 or 0, respectively). This binary format was converted to a nucleotide sequence (1 = G and 0 = A); therefore, fingerprint profiles could be aligned and a neighbor-joining tree could be constructed based on these profiles using Genotyper (Fig. 1) or ClustalX and Treeview (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of 32 Irish H. pylori isolates. The neighbor-joining network was developed from the binary data obtained by the Genotyper macro. The scale at the bottom shows percentage heterogeneity among the isolates based on sharing of FAFLP fragments.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of various H. pylori isolates from different geographic regions. The neighbor-joining network was developed from the binary data obtained by the Genotyper macro. Clustering of isolates is based on sharing of FAFLP fragments. Clustering resulted in two main clusters (1 and 2) and six distinct subgroups (A to F).

As vacA and insertion-deletion genotyping suggested potential geographic relationships between Irish H. pylori isolates and isolates from specific countries in East Asia and from Northern Europe, respectively, FAFLP-PCR analysis was applied. This technique encompasses the whole genome rather than specific loci and has been previously used to determine the geographic relationship of H. pylori isolates [Ahmed et al., Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291(Suppl. 31):D-11, 2001]. FAFLP-PCR analysis was used to examine 45 of the 74 Irish H. pylori isolates. Of these 45 isolates, 32 (71%) yielded informative profiles. The remaining 13 isolates either did not yield profiles with all three selective primers or did not yield profiles at all. However, the 32 characterizable isolates were still genotypically representative of the larger set of isolates. Twenty-five of these isolates (78%) yielded insertion-deletion motifs (type II, 13 [52%]; type IV, 9 [36%]; type Ia, 2 [8%]; type IIIb, 1 [4%]), while the remaining isolates were not typeable by insertion-deletion analysis (7 [22%] of the 32 isolates; cf. with 11 of 74 [15%]). The distribution of the vacA alleles in this selected group of isolates was s1a m2 (19 [60%]), s1a m1 (10 [31%]), and s2 m2 (3 [9%]). The amplification reactions yielded unique profiles for each isolate, and a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed based on these profiles (Fig. 1). Analysis of this tree showed that the majority (28 [87.5%]) of isolates in this group differ in percentage heterogeneity by approximately 7.8% with respect to their FAFLP profiles. This supports earlier observations by which there appears to be a relative genetic restriction of vacA alleles and insertion-deletion motifs, indicating that Irish H. pylori isolates are weakly clonal.

Seven FAFLP-PCR profiles randomly chosen from among those obtained for Irish isolates plus 22 profiles previously generated in the same way at the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics for strains encompassing six different geographic regions [Ahmed et al., Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291(Suppl. 31):D-11, 2001] were phylogenetically analyzed. The binary data obtained from FAFLP-PCR analysis were used to construct a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2). This tree shows two main clusters (1 and 2) and six subgroups (A to F). The fingerprints used to construct this tree were previously generated by using only one selective primer, whereas fingerprints generated by three selective primers were used to construct Fig. 1. Using only one selective primer reduces the sensitivity of the technique. This explains why isolate FR165 shows about 9% heterogeneity with respect to isolates J563 and MI571 in Fig. 1, while these isolates show little difference in Fig. 2. However, each fingerprint is still unique to each isolate and the geographic separation of isolates can clearly be seen in Fig. 2. Subgroups A, B, and C are in cluster 1 and subgroups D, E, and F are in cluster 2. Each subgroup contained either isolates from one region or a combination of isolates from different geographic locations (A, mainly India; B, mainly United Kingdom; C, Ireland; D, mainly United Kingdom and Spain; E, mainly Spain and Peru; and F, Spain, Peru, and Africa). The fact that Irish H. pylori isolates do not cluster with isolates from any other region suggests that they may have a unique genotype and are distinct from those from other regions. However, the Irish isolates do reside in cluster 1 with Asian and United Kingdom isolates, demonstrating that they are more like isolates from these regions than like Spanish, Peruvian, and African isolates. These findings are in accordance with a recent study that demonstrated that Indian and European H. pylori isolates grouped in the same subpopulation and that East Asian and a subset of European isolates share an ancestral relationship and diverged from each other recently (9).

As indicated by the present genotyping study and by other studies (22), Irish H. pylori isolates appear to exhibit restricted diversity. The clustering of the Irish isolates into one subgroup (C) by FAFLP-PCR confirms that Irish isolates are weakly clonal. This weakly clonal behavior was not observed within strains from other geographic regions, as some isolates from specific regions clustered in two or three different subgroups (Indian isolates clustered in subgroups A, B, and E, United Kingdom isolates clustered in subgroups B and D, Peruvian isolates clustered in subgroups D, E, and F, and Spanish isolates clustered in subgroups A, D, E, and F). The clustering of Peruvian and Spanish isolates (Fig. 2) is in accordance with previous studies (14).

In summary, the results obtained for this study suggest that Irish H. pylori isolates have associations with Northern European isolates, as revealed by insertion-deletion analysis. Yet the vacA allelic predominance among these Irish isolates displays similarities with isolates from China and Taiwan. Further, FAFLP-PCR genotyping confirmed that Irish isolates are weakly clonal, display more homogeneous fingerprint profiles than do isolates from other geographic locations, and have some associations with both European and Asian isolates. These three genotyping techniques show that Irish H. pylori isolates have distinctive features that may have evolved in this insular European population.

Acknowledgments

Ian Carroll was the recipient of a postgraduate studentship from the Health Research Board (HRB) of Ireland, whose support is gratefully acknowledged. Niyaz Ahmed acknowledges with thanks a research grant from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

We thank Douglas E. Berg and Asish Mukhopadhyay for the supply of genomic DNA from H. pylori isolates from non-Irish and non-Indian origins, originally obtained by Robert H. Gilman, Teresa Alarcon, Manuel Lopez Brea, and John Atherton, and Seyed E. Hasnain for his suggestions and encouragement. We also thank Ross Fitzgerald for his helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., T. Azuma, D. E. Berg, Y. Ito, G. Morelli, Z.-J. Pan, S. Suerbaum, S. A. Thompson, A. van der Ende, and L.-J. van Doorn. 1999. Recombination and clonal groupings within Helicobacter pylori from different geographical regions. Mol. Microbiol. 32:459-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, N., A. Bal, A. A. Khan, M. Alam, A. Kagal, V. Arjunwadkar, A. Rajput, A. A. Majeed, S. A. Rahman, S. Banerjee, S. Joshi, and R. Bharadwaj. 2002. Whole genome fingerprinting and genotyping of multiple drug resistant (MDR) isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from endophthalmitis patients in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 1:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atherton, J. C., P. Cao, R. M. Peek, Jr., M. K. R. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and T. L. Cover. 1995. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17771-17777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bereswill, S., R. Schonenberger, C. Thies, F. Stahler, S. Strobel, P. Pfefferle, L. Wille, and M. Kist. 2000. New approaches for genotyping of Helicobacter pylori based on amplification of polymorphisms in intergenic DNA regions at the insertion site of the cag pathogenicity island. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 189:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser, M. J. 1992. Helicobacter pylori: its role in disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:386-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser, M. J., G. I. Perez-Perez, H. Kleanthous, T. L. Cover, R. M. Peek, P. H. Chyou, G. N. Stemmermann, and A. Nomura. 1995. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 55:2111-2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai, M., A. Tanna, R. Wall, A. Efstratiou, R. George, and J. Stanley. 1998. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of an outbreak of group A streptococcal invasive disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3133-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dundon, W. G., D. G. Marshall, C. A. O'Morain, and C. J. Smyth. 2000. Population characteristics of Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates: a tRNA-associated locus. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 169:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falush, D., T. Wirth, B. Linz, J. K. Pritchard, M. Stephens, M. Kidd, M. J. Blaser, D. Y. Graham, S. Vacher, G. I. Perez-Perez, Y. Yamaoka, F. Megraud, K. Otto, U. Reichard, E. Katzowitsch, X. Wang, M. Achtman, and S. Suerbaum. 2003. Traces of human migrations in Helicobacter pylori populations. Science 7:1582-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go, M. F., V. Kapur, D. Y. Graham, and J. M. Musser. 1996. Population genetic analysis of Helicobacter pylori by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis: extensive allelic diversity and recombinational population structure. J. Bacteriol. 178:3934-3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulding, J. N., J. V. Hookey, J. Stanley, W. Olver, K. R. Neal, D. A. A. Ala'Aldeen, and C. Arnold. 2000. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism genotyping of Neisseria meningitidis identifies clones associated with invasive disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4580-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grady, R., G. O'Neill, B. Cookson, and J. Stanley. 2000. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of the MRSA epidemic. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187:27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito, Y., T. Azuma, S. Ito, H. Miyaji, M. Hirai, Y. Yamazaki, F. Sato, T. Kato, Y. Kohli, and M. Kuriyama. 1997. Analysis and typing of the vacA gene from cagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori isolated in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1710-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersulyte, D., A. K. Mukhopadhyay, B. Velapatiño, W. Su, Z. Pan, C. Garcia, V. Hernandez, Y. Valdez, R. S. Mistry, R. H. Gilman, Y. Yuan, H. Gao, T. Alarcón, M. López-Brea, G. Balakrish Nair, A. Chowdhury, S. Datta, M. Shirai, T. Nakazawa, R. Ally, I. Segal, B. C. Wong, S. K. Lam, F. O. Olfat, T. Borén, L. Engstrand, O. Torres, R. Schneider, J. E. Thomas, S. Czinn, and D. E. Berg. 2000. Differences in genotypes of Helicobacter pylori from different human populations. J. Bacteriol. 182:3210-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, S. Y., C. W. Woo, Y. M. Lee, B. R. Son, J. W. Kim, H. B. Chae, S. J. Youn, and S. M. Park. 2001. Genotyping cagA, vacA subtype, iceA1, and babA of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Korean patients, and their association with gastroduodenal diseases. J. Korean Med. Sci. 16:579-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin, C.-W., S.-C. Wu, S.-C. Lee, and K.-S. Cheng. 2000. Genetic analysis and clinical evaluation of vacuolating cytotoxin gene A and cytotoxin-associated gene A in Taiwanese Helicobacter pylori isolates from peptic ulcer patients. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall, D. G., W. G. Dundon, S. M. Beesley, and C. J. Smyth. 1998. Helicobacter pylori—a conundrum of genetic diversity. Microbiology 144:2925-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miehlke, S., C. Kirsch, K. Agha-Amiri, T. Günther, N. Lehn, P. Malfertheiner, M. Stolte, G. Ehninger, and E. Bayerdörffer. 2000. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA are associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int. J. Cancer 1:322-327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan, Z. J., D. E. Berg, R. W. van der Hulst, W. W. Su, A. Raudonikiene, S. D. Xiao, J. Dankert, G. N. Tytgat, and A. van der Ende. 1998. Prevalence of vacuolating cytotoxin production and distribution of distinct vacA alleles in Helicobacter pylori from China. J. Infect. Dis. 178:220-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsonnet, J., G. D. Friedman, D. P. Vandersteen, Y. Chang, J. H. Vogelman, N. Orentreich, and R. K. Sibley. 1991. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 325:1127-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pride, D. T., R. J. Meinersmann, and M. J. Blaser. 2001. Allelic variation within Helicobacter pylori babA and babB. Infect. Immun. 69:1160-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan, K. A., A. P. Moran, S. O. Hynes, T. Smith, D. Hyde, C. A. O'Morain, and M. Maher. 2000. Genotyping of cagA and vacA, Lewis antigen status, and analysis of the poly(C) tract in the alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase gene of Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strobel, S., S. Bereswill, P. Balig, P. Allgaier, H.-G. Sonntag, and M. Kist. 1998. Identification and analysis of a new vacA genotype variant of Helicobacter pylori in different patient groups in Germany. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1285-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Doorn, L.-J., C. Figueiredo, F. Mégraud, S. Pena, P. Midolo, D. M. De Magalhäes Queiroz, F. Carneiro, B. Vanderborght, M. D. G. F. Pegado, R. Sanna, W. De Boer, P. M. Schneeberger, P. Correa, E. K. W. Ng, J. Atherton, M. J. Blaser, and W. G. V. Quint. 1999. Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 116:823-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaoka, Y., T. Kodama, O. Gutierrez, J. G. Kim, K. Kashima, and D. Y. Graham. 1999. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori iceA, cagA, and vacA status and clinical outcome: studies in four different countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2274-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]