Abstract

Objectives

25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) deficiency and excess activity of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) are both associated with cardiovascular disease. Vitamin D interacts with the vitamin D receptor (VDR) to negatively regulate renin expression in mice; however, human studies linking genetic variation in the VDR with renin are lacking. We evaluated: 1) whether genetic variation in the VDR at the Fok1 polymorphism was associated with plasma renin activity (PRA) in a population of hypertensives and a separate population of normotensives; and 2) whether the association between Fok1 genotype and PRA was independent of 25(OH)D levels.

Design/Patients/Measurements

Genetic association study, assuming an additive model of inheritance, of 375 hypertensive and 146 normotensive individuals from the HyperPATH cohort, who had PRA assessments after 1 week of high dietary sodium balance (HS) and l week of low dietary sodium balance (LS).

Results

The minor allele (T) at the Fok1 ploymorphism was significantly associated with lower PRA in hypertensives (LS: β= −0.22, P<0.01; HS: β= −0.19, P<0.01); when repeated in normotensives, a similar relationship was observed (LS: β= −0.17, P<0.05; HS: β= −0.18, P=0.14). In multivariable analyses, both higher 25(OH)D levels and the T allele at Fok1 were independently associated with lower PRA in hypertensives, however, 25(OH)D was not associated with PRA in normotensives.

Conclusions

Genetic variation at the Fok1 polymorphism of the VDR gene, in combination with 25(OH)D levels, was associated with PRA in hypertension. These findings support the vitamin D-VDR complex as a potential regulator of renin activity in humans.

KEY TERMS: vitamin D, renin, polymorphism, Fok1, VDR

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin D deficiency and excess activity of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) have both been associated with cardiovascular diseases 1–4. Vitamin D negatively regulates renin expression via its interactions with the vitamin D receptor (VDR), linking vitamin D physiology with activity of the RAS 5, 6.

Li et al. showed that VDR knock-out mice displayed a phenotype of high plasma renin activity (PRA) and hypertension that was ameliorated with RAS antagonism 5. Inhibiting the production of active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2D) by inactivating the 1α-hydroxylase enzyme also resulted in high PRA, which was reduced with administration of 1,25(OH)2D 7. In contrast, over-expression of the VDR in juxtaglomerular cells of mice suppressed renin expression independently of parathyroid hormone and calcium 8. These findings have been consolidated by implicating vitamin D as an inhibitor of renin gene expression via its interaction with the VDR 2, 6, 9.

Cross-sectional human studies, including our own, have observed similar relationships between vitamin D and the RAS; vitamin D metabolites have been inversely associated with circulating renin, PRA 10–13, and vascular tissue RAS activity 14, 15. However, to our knowledge, these phenotypic relationships have not been correlated with genetic variation of the VDR gene in humans.

The Fok1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is arguably the most studied SNP within the VDR gene 16, 17; it represents a missense mutation in the translation initiation site which modifies the length and functional activity of the VDR protein 16, 17. The clinical significance of this SNP is highlighted by its associations with several adenocarcinomas 18, 19, bone mineralization 16, 20, 21, fracture risk 22, 23, and 25- hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels 17, 20.

Given the previously identified importance of the Fok1 SNP in the biology of the VDR, and the lack of studies evaluating the link between VDR genetics and the RAS, we assessed the association of genetic variation at the Fok1 SNP with PRA in a Caucasian hypertensive population that underwent a rigorous phenotyping protocol for PRA, including dietary sodium and body posture control. Subsequently, we evaluated the same association in a separate population of Caucasian normotensives who completed the same study procedures; thus, representing a distinct study population with reliable phenotyping of PRA. Since we have previously observed an inverse association between 25(OH)D and PRA 13, we also investigated the inter-relationship between Fok1genotype and 25(OH)D in predicting PRA. Demonstrating a relationship between PRA and variation in the VDR would further support the biologic roles of 1,25(OH)2Dand the VDR in regulating renin.

METHODS

Study Population

This cross-sectional analysis was performed on data gathered from subjects studied in the International Hypertensive Pathotype (HyperPATH) Consortium. The HyperPATH study is an on-going, multi-site study, aimed at investigating the pathophysiologic and genotypic mechanisms involved in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. A particular strength of the HyperPATH study design is its rigorous study protocol (described below), conducted in Clinical Research Centers, and designed to minimize notable confounders of PRA (dietary sodium intake, body posture, diurnal variation, and medications); these approaches reduce variation in PRA measurements and enhance the power to detect real differences with relatively small sample sizes. Participants in this analysis were studied at four collaborating centers: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA), University of Utah Medical Center (Salt Lake City, UT), Vanderbilt University Hospital (Nashville, TN), and Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou (Paris, France). The Brigham and Women’s Hospital served as the central laboratory for all lab processing. Although results from the HyperPATH cohort have been previously reported, the current described analyses are original and have not been published.

Subjects with chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease, heart failure, suggested or known causes of secondary hypertension, and active malignancy were not enrolled in the HyperPATH study. Enrolled subjects were classified as having hypertension if they had an untreated seated diastolic blood pressure (DBP) > 100 mmHg, a DBP > 90 mmHg with one or more antihypertensive medications, measured as the average of three readings with standard manual sphygmomanometer, or the use of two or more antihypertensive medications. Enrolled subjects were classified as normotensive if the average of three consecutive seated blood pressure readings was less than 140/90 mmHg, and they had no first-degree relatives diagnosed with hypertension prior to the age of 60 years. Study procedures included dietary sodium modulation to maintain high-sodium (HS) and low-sodium balance (LS) in sequence (below).

The association between Fok1 and PRA was assessed in the hypertensive population first, and then subsequently evaluated in the normotensive population. This approach facilitated our effort to evaluate this relationship in more than one independent population with reliable phenotyping of the outcome variable PRA. Since the Fok1 polymorphism, RAS activity, and 25(OH)D levels are known to be confounded by race and ethnicity 16, 24, 25, the final study population for this analysis was restricted to Caucasian subjects who were successfully maintained in sodium balance per study protocols (below) and had successful genotyping of Fok1 from available frozen blood (n=375 subjects with hypertension, n=146 subjects with normotension). From this total study population, 25(OH)D concentrations were measured at a later date on the subset of subjects who had remaining frozen blood available for assay (n=223 subjects with hypertension, n=111 subjects with normotension).

The HyperPATH Study Protocol to Phenotype PRA

To avoid interference with PRA assessment, hypertensive participants taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, were withdrawn from these medications three months before study initiation. Beta-blockers and diuretics were withdrawn one month before study initiation. If needed for blood pressure control, hypertensive subjects were treated with amlodipine and/or hydrochlorothiazide temporarily; however, these medications were stopped three weeks prior to laboratory evaluation of PRA.

Subjects were maintained in HS (≥200 mmol Na/24h) and then LS (≤10 mmol Na/24h), for 5–7 days each. Both study diets also included fixed quantities of potassium (80 mmol/day) and calcium (1000mg/day). After each diet phase, participants were admitted to the institutional Clinical Research Center and maintained in a supine position overnight. For each diet phase, baseline blood sampling was obtained in the morning and used to measure PRA, and then frozen without preservatives until assayed for future use. Baseline blood pressure was determined while supine between the hours of 8:00 AM and 10:00 AM, following 10 hours of overnight rest using the average of five readings from a Dinamap automated device (Critikon, Tampa, FL). Sodium balance and diet compliance were confirmed on admission to the Clinical Research Center with a 24-hr urine sodium excretion of ≥ 150 mmol for HS, and ≤ 30 mmol for LS. Study protocols were approved by the Human Subjects Committees/Institutional Review Boards at each location, and informed written consent was obtained from each subject.

Biochemical Assessments

All subjects had PRA measured from the baseline morning supine blood obtained on the first day of study on each diet using the Diasorin assay (Stillwater, MN). At a later date, a majority subset of subjects (above) also had a single 25(OH)D level measured from the remaining baseline frozen blood samples obtained on the first day of study using the Diasorin assay. Since 25(OH)D was measured from stored frozen samples, we thawed, aliquoted, and measured 25(OH)D levels from 19 participants who also had 25(OH)D levels measured on fresh samples from the original day of study. The correlation coefficient comparing levels from fresh and frozen samples was 0.9714.

VDR genotyping

The VDR gene is a large gene (> 100 Kb) located on chromosome 12q13. The Fok1 SNP (rs2228570, formerly known as rs10735810) lies within exon 2 and is characterized by a cytosine or thymidine nucleotide variant. DNA from each subject was extracted from peripheral leukocytes obtained from frozen blood samples 26. Genotyping of the Fok1SNP was conducted using the Applied Biosystems 3100 genetic analyzer with a completion rate of 98.5%. The genotype frequencies in the hypertensive population were 119 for cytosine homozygotes (CC), 195 for heterozygotes (CT), and 61 for thymidine homozygotes (TT) and were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium by χ2 testing (P=0.20). The genotype frequencies in the normotensive population were 62 for CC, 66 for CT, and 18 for TT and were also in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium by χ2 testing (P=0.95).

Statistical Methods

Analyses were performed to first evaluate the association of PRA and Fok1 genotype assuming an additive model in the hypertensive population. In efforts to substantiate the associations seen in hypertensives, the same analyses were subsequently evaluated in a normotensive population. Though the normotensive population was smaller in size, it represented a distinctly unique phenotypic population with PRA measures. To contextualize our previously reported inverse association between 25(OH)D and PRA13 with the VDR, we investigated whether the association between Fok1 genotype and PRA was independent of, or modified by, 25(OH)D levels.

Linear regression was employed to test the associations between PRA and frequency of the T allele at Fok1 (categorized as CC, CT, or TT). All linear regression models included adjustments for sibling relatedness using a mixed effects model and are reported with effect estimates (β), the 95% confidence intervals for β, and the corresponding p-value. The level for significance for all tests conducted was set at α=0.05 and reported as two-tailed P-values. Data analyses were performed using SAS v9.1 (Cary, NC) statistical software. Because PRA was not normally distributed, it was transformed using the natural logarithm to normalize its distribution. For graphical representation, PRA values were untransformed using the natural exponential and plotted as mean values with the 95% confidence intervals for the mean. Because age is a known independent predictor of PRA, we adjusted for age in all multivariable linear regression models. Since 25(OH)D has been inversely associated with PRA in our hypertensive population 13, we also adjusted for 25(OH)D (categorized as <37.5, 37.5–75, and ≥ 75 nmol/L; divide by 2.5 to convert to ng/mL) in the subset of subjects who had it measured, to test whether Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D were both independently associated with PRA when evaluated together. We also explored whether a potential interaction between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D was associated with PRA using an adjusted interaction model that included age, 25(OH)D, Fok1 genotype, and an interaction term between 25(OH)D and Fok1 genotype.

RESULTS

Study Populations

Consistent with prior reports from the HyperPATH cohort 27, the hypertensive study population was older, male-predominant, and had a higher BMI than the normotensive population (Table 1). Both populations were vitamin D insufficient according to current consensus28. As previously observed27, although both populations demonstrated appropriate PRA responses to dietary sodium manipulation, physiologic suppression and stimulation of PRA was blunted in hypertensives when compared to normotensives (Table 1); further illustrating the differences in RAS physiology between the two populations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the hypertensive and normotensive study populations.

Values are represented as means with standard deviations for all variables except PRA, which was not normally distributed, and is represented by the median and the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile). (25[OH]D=25-hydroxyvitamin D; LS=low dietary sodium balance; HS=high dietary sodium balance; SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure).

| HYPERTENSIVE Study Population | NORMOTENSIVE Study Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 375 | 146 | |

| Age (years) | 48.3 (8.2) | 39.9 (10.9) | |

| Gender (%female) | 39.0 | 56.2 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 (3.9) | 24.4 (3.7) | |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 56.0 (23.1) | 60.8 (20.5) | |

| Frequency of T (minor) allele | 0.42 | 0.35 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | LS | 132.2(18.4) | 105.3(10.3) |

| HS | 146.8(20.3) | 109.8(11.4) | |

| DBP (mmHg) | LS | 79.9(11.0) | 63.1(7.0) |

| HS | 87.5(11.4) | 66.1(8.1) | |

| PRA (μg/L/h) | LS | 1.90 (1.00, 3.40) | 2.48 (1.60, 4.20) |

| HS | 0.48 (0.20, 0.80) | 0.34 (0.20, 0.59) | |

| 24hr urine sodium (mmol) | LS | 16.1(19.8) | 11.4(17.6) |

| HS | 216.2(74.9) | 226.1(78.0) | |

Fok1 genotype and PRA in Hypertensives

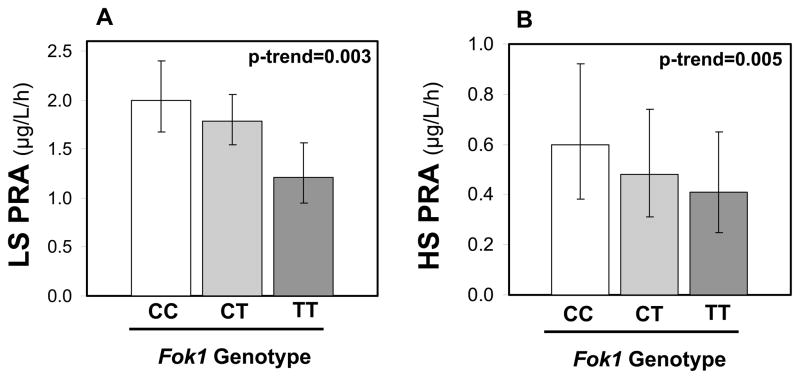

The relationship between Fok1 genotype and PRA was evaluated under controlled dietary sodium conditions in hypertensives. Under both dietary conditions, the T allele was associated with lower PRA (LS: β= −0.219, [−0.362, −0.076], P-trend=0.003; HS: β= −0.197, [−0.334, −0.059], P-trend=0.005) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The adjusted relationships between Fok1 genotype and PRA in hypertensives in LS balance (A) and HS balance (B). Bars represent the untransformed PRA and whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval. The population by genotype was n=119 for CC, n=195 for CT, and n=61 for TT.

Fok1 genotype and PRA in Normotensives

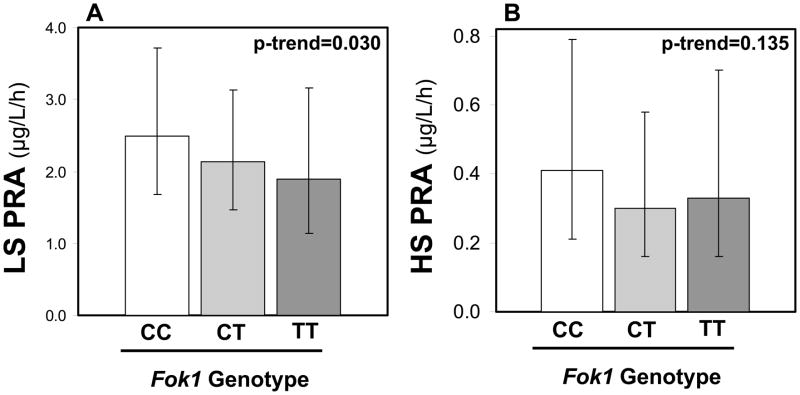

The relationship between Fok1 genotype and PRA was subsequently evaluated in the smaller normotensive cohort. Similar inverse associations were observed between the T allele and PRA; this was particularly evident in LS conditions where the variation in PRA was maximal, but did not achieve statistical significance in HS conditions where PRA was suppressed (LS: β= −0.165, [−0.313, −0.016 ], P-trend=0.030; HS: β= −0.181, [−0.419, −0.057], P-trend=0.135) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The adjusted relationships between Fok1 genotype and PRA in normotensives in LS balance (A) and HS balance (B). Bars represent the untransformed PRA and whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval. The population by genotype was n=62 for CC, n=66 for CT, and n=18 for TT.

The Inter-relationship Between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D

Since 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations have previously been inversely associated with PRA 10–12, including in this hypertensive HyperPATH population 13, and the VDR is hypothesized to mediate the association between 1,25(OH)2D and PRA, we investigated the inter-relationship between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D in predicting PRA. When Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D status (categorized as: <37.5, 37.5–75, and ≥ 75 nmol/L) were evaluated together in the hypertensive population, they both remained independently associated with PRA irrespective of dietary sodium balance (Table 2). However, we found no interaction between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D in predicting PRA in hypertensives (HS: P-interaction=0.58; LS: P-interaction=0.74), suggesting that the frequency of the T allele at Fok1 and higher 25(OH)D concentrations may have additive, rather than dependent, associations with PRA.

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regressions results evaluating the independent associations of Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D status on PRA in hypertensives maintained in dietary sodium balance. (LS=low dietary sodium balance; HS=high dietary sodium balance; 25(OH)D status categorized as <37.5, 37.5–75, and ≥ 75 nmol/L)

| LS | HS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Effect Estimate (β) | 95% Confidence Intervals for β | P | Effect Estimate (β) | 95% Confidence Intervals for β | P |

| Age (years) | −0.038 | [−0.054, −0.023] | <0.0001 | −0.004 | [−0.020, 0.012] | 0.65 |

| 25(OH)D status | −0.242 | [−0.432, −0.052] | 0.013 | −0.229 | [−0.413, −0.044] | 0.015 |

| Fok1 genotype (T allele) | −0.267 | [−0.454, −0.082] | 0.005 | −0.278 | [−0.455, −0.100] | 0.002 |

We subsequently evaluated whether Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D were independent predictors of PRA in the smaller normotensive population. The T allele at Fok1 remained significantly associated with PRA, in LS balance where variability of PRA was maximal, but was a non-significant trend in HS conditions (Table 3). Vitamin D status was not significantly associated with PRA in normotensives. As was the case in hypertensives, we observed no significant interaction between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D in predicting PRA (HS: P-interaction=0.39; LS: P-interaction=0.83).

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regressions results evaluating the independent associations of Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D status on PRA in normotensives maintained in dietary sodium balance. (LS=low dietary sodium balance; HS=high dietary sodium balance; 25(OH)D status categorized as <37.5, 37.5–75, and ≥ 75 nmol/L)

| LS | HS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Effect Estimate (β) | 95% Confidence Intervals for β | P | Effect Estimate (β) | 95% Confidence Intervals for β | P |

| Age (years) | −0.019 | [−0.038, −0.001] | 0.036 | −0.024 | [−0.045, −0.003] | 0.025 |

| 25(OH)D status | −0.087 | [−0.334, 0.160] | 0.485 | 0.086 | [−0.246, 0.417] | 0.610 |

| Fok1 genotype (T allele) | −0.219 | [−0.425, −0.013] | 0.038 | −0.250 | [−0.548, 0.047] | 0.099 |

Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D concentration

Prior studies have reported an association between Fok1 genotype and concentrations of 25(OH)D 17. In contrast, we did not observe any relationship between 25(OH)D concentrations and Fok1 genotype in hypertensives (β= −0.03, [−4.70, 4.64], P-trend=0.99), or normotensives (β= −1.14, [−7.14, 4.87], P-trend=0.71).

DISCUSSION

Vitamin D deficiency is an epidemic 28, 29 that has been associated with heightened RAS activity and cardiovascular disease 1, 2. Animal experiments have demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D is a negative regulator of renin expression via its interactions with the VDR5, 8. These findings have been translated to human cross-sectional studies that have established an inverse association between circulating vitamin D metabolites and PRA 10–13; however, human genetic studies implicating the VDR gene in this relationship have not been reported. This paucity of human genetic association studies may be related to the difficulty in acquiring reliable phenotyping of PRA in a sufficiently large human population. In this study, we observed that increasing frequency of the T allele at the Fok1 VDR gene polymorphism was independently associated with lower PRA in a large population of meticulously characterized hypertensives. Similar trends were observed in a smaller independent population of normotensives, especially when maintained in LS balance. We also demonstrated that both vitamin D and VDR genotype were independently associated with PRA in hypertensives. These findings may represent further evidence that the relationship between vitamin D and PRA is mediated by the VDR, and to our knowledge, is the first report linking VDR polymorphisms to PRA in humans.

The Fok1 SNP is arguably the most studied polymorphism in the VDR gene, and has been previously associated with several cancers, bone density, fracture risk, and 25(OH)D levels 17–23; thus, it represents a logical and attractive polymorphism with which to evaluate the role of genetic variation in the VDR with PRA. The Fok1 SNP is also considered to be a functional polymorphism of the VDR, and because it is not in linkage disequilibrium with other VDR SNPs, associations with Fok1 genotype are considered independent markers of the VDR gene 16. Some in vitro studies in cell lines (HeLa and fibroblast) have suggested that the C allele results in a shorter VDR protein variant (424 amino acid) that is more active than the longer VDR protein variant associated with the T allele (427 amino acids) 16, 17, 30–32. These studies assessed “functionality” of the VDR using transcriptional activation with reporter constructs under the control of vitamin D responsive elements. In contrast, similar in vitro experiments by other investigators failed to show a difference in functional activity between these VDR protein variants33. In vivo human studies have shown mixed results; the T allele at Fok1 has been associated with decreased bone mineralization, but also higher 25(OH)D levels17, 20. We observed lower PRA with the TT genotype at Fok1, suggesting that if genetic variation at the Fok1 SNP influences the activity of the VDR, then the T allele would confer increased activity using PRA as a functional read-out. This is in contrast to prior in vitro studies suggesting increased VDR activity with the C allele at Fok1, but may be consistent with in vivo findings suggesting increased 25(OH)D production with the TT genotype20. Our observations may further support the notion that different vitamin D target genes could have varying sensitivities and interactions with VDR protein variants resulting from Fok1 genotypes. Since we did not characterize the VDR protein variants in our subjects, nor perform functional assays on them, we are limited in making further conclusions in reference to VDR protein activity.

Our findings support the hypothesis that the negative regulation of renin by 1,25(OH)2D is mediated in part by the VDR6. Our study population was maintained free of all blood pressure medications and in strict dietary sodium balance; we expect that both of these study procedures substantially increased the reliability and validity of our outcome variable, PRA. We observed the same significant findings under both dietary conditions in hypertension; thus, despite the variation in PRA amplitudes induced by dietary sodium manipulation, the T allele at Fok1 was associated with lower PRA. The confidence in this genetic association would be enhanced if it could be replicated in an independent, and ideally larger, population of hypertensives. A major challenge in conducting this replication experiment, however, is the lack of another known cohort of hypertensive individuals who have undergone appropriate control of known contributors of variability in PRA (salt intake, body posture, medication washout) and genotyping of Fok1. Realizing this limitation, we tested the association between Fok1 genotype and PRA within the normotensive population of the HyperPATH cohort. Despite the smaller size of this population, we observed that the T allele at Fok1 was again associated with lower PRA; although this was only statistically significant in LS balance, where the larger variability in unsuppressed PRA gave us greater power to detect the trend. These corroborative trends in normotensives may serve as a practical replication of our findings in hypertensives, albeit in a less than ideal sample size and with marginal statistical significance.

Consistent with studies by Resnick et al. and Tomaschitz et al. showing an inverse relationship between vitamin D metabolites and PRA, we also previously demonstrated that increasing 25(OH)D status was associated with lower PRA in this population of hypertensives 13. Since we speculate that the mechanism of this association between 25(OH)D and PRA is ultimately mediated via the VDR, we investigated whether there was an interaction between 25(OH)D and Fok1 in relation to PRA. We found that both frequency of the T allele at the Fok1 SNP and higher 25(OH)D concentrations were independently associated with lower PRA in hypertensives, and did not interact with each other in predicting PRA, supporting an additive relationship between vitamin D levels and variation in the VDR with PRA. However, we may have been underpowered to conclusively exclude a statistical interaction between Fok1 genotype and 25(OH)D due to a combination of small sample size and effect sizes. Since only 15% of hypertensives with a TT genotype had 25(OH)D levels ≥ 75 nmol/L, a larger sample size would likely be needed to adequately assess for interaction, particularly a sample with a broader distribution of 25(OH)D levels. In normotensives, 25(OH)D was not associated with PRA; this may suggest that the effect size of vitamin D concentrations in predicting PRA in normotensives was small when compared to Fok1 genotype, and/or that the sample size of normotensives was too small to conclusive determine this relationship.

Our results must be interpreted within the context of our study design. First, this analysis was cross-sectional, and thus cannot prove causality or directionality of associations. Though our population size was small for a genetic association study, our meticulous phenotyping protocol enhanced the ability to detect differences in PRA. Futhermore, the consistent direction of association in each dietary condition among both the hypertensive and normotensive populations support our conclusions. Parathyroid hormone has been associated with PRA 34; however, whether its role is independent of vitamin D metabolites remains unresolved 8. Our study design controlled for dietary sodium and calcium intake, but we did not have ionized calcium, parathyroid hormone, or 1,25OH2D measurements that could have shed further insight on potential interacting mechanisms. The generalizability of our findings is limited to the population we analyzed, a relatively homogenous group of Caucasians; this demographic restriction limited possible confounding by race and ethnicity16, 24. Though our study design controlled for many major confounders of PRA, several other factors that are known (estrogen status, stress, sympathetic nervous system activity) or not known to affect PRA may have influenced our measurements 35. Recent studies have suggested that VDR agonists may reduce renal injury36 and that VDR genotypes (including Fok1) associate with end-stage renal disease37. Though our entire study population had normal renal function on enrollment (calculated glomerular filtration rate [GFR] > 60 mL/min), the majority of them did not have further assessments of their GFR under each dietary condition. Thus, we are limited in evaluating whether diet-induced changes in GFR influence the relationship between Fok1 and PRA.

Emerging evidence continues to implicate vitamin D deficiency with cardiovascular diseases and implicates the RAS as a likely contributor2. Herein, we demonstrate that in addition to the independent association between vitamin D metabolites and PRA, genetic variation of the VDR protein may also independently influence PRA. These findings further support the biologic role of 1,25(OH)2D as an inhibitor of renin expression in humans, and suggest that the combination of 25(OH)D status and genetic variation at the Fok1 SNP may enhance prediction of PRA and RAS activity, which may in turn be relevant for cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Future studies to confirm these associations and correlate functional studies on the VDR protein are needed.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES: F32 HL104776-01 (AV), T32HL007609-24 (BS), K08 HL079929 (JPF), K23 HL08236-03 (JSW), U54LM008748 from the National Library of Medicine and UL1 RR025758, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources and M01-RR02635, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, General Clinical Research Center, from the National Center for Research Resources, and the Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) in Molecular Genetics of Hypertension P50HL055000. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health or the National Center for Research Resources.

We would like to thank the staff and faculty at our collaborating institutions, including the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Centre Investigation Clinique, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, the University of Utah Medical Center, and Vanderbilt University Hospital. Funding support courtesy of National Institutes of Health grants F32 HL104776-01 (AV), T32HL007609-24 (BS), K08 HL079929 (JPF), K23 HL08236-03 (JSW), U54LM008748 from the National Library of Medicine and UL1 RR025758, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources and M01-RR02635, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, General Clinical Research Center, from the National Center for Research Resources, and the Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) in Molecular Genetics of Hypertension P50HL055000. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health or the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURES: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaidya A, Forman JP. Vitamin D and Hypertension: current evidence and future directions. Hypertension. 2010;56:774–779. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzolai L, Nussberger J, Aubert JF, et al. Blood pressure-independent cardiac hypertrophy induced by locally activated renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 1998;31:1324–1330. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.6.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dluhy RG, Williams GH. Aldosterone--villain or bystander? N Engl J Med. 2004;351:8–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:229–238. doi: 10.1172/JCI15219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, et al. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:726–776. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou C, Lu F, Cao K, et al. Calcium-independent and 1,25(OH)2D3-dependent regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in 1alpha-hydroxylase knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2008;74:170–179. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong J, Qiao G, Zhang Z, et al. Targeted vitamin D receptor expression in juxtaglomerular cells suppresses renin expression independent of parathyroid hormone and calcium. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1577–1581. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan W, Pan W, Kong J, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses renin gene transcription by blocking the activity of the cyclic AMP response element in the renin gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29821–29830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resnick LM, Muller FB, Laragh JH. Calcium-regulating hormones in essential hypertension. Relation to plasma renin activity and sodium metabolism. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:649–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-5-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnick LM, Nicholson JP, Laragh JH. Calcium metabolism in essential hypertension: relationship to altered renin system activity. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2739–2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaschitz A, Pilz S, Ritz E, et al. Independent association between 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the renin-angiotensin system The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health (LURIC) Study. Clin Chim Acta. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaidya A, Forman JP, Williams JS. 25-hydroxyvitamin D is Associated with Plasma Renin Activity and the Pressor Response to Dietary Sodium Intake in Caucasians. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1470320310391922. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman JP, Williams JS, Fisher ND. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and regulation of the renin-angiotensin system in humans. Hypertension. 2010;55:1283–1288. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.148619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaidya A, Forman JP, Fisher ND, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency Blunts Vascular Sensitivity to Angiotensin II in Obesity. The Journal of Human Hypertension. 2010 doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.110. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uitterlinden AG, Fang Y, Van Meurs JB, et al. Genetics and biology of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Gene. 2004;338:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Burne TH, et al. A systematic review of the association between common single nucleotide polymorphisms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randerson-Moor JA, Taylor JC, Elliott F, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms, serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, and melanoma: UK case-control comparisons and a meta-analysis of published VDR data. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3271–3281. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostner K, Denzer N, Muller CS, et al. The relevance of vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms for cancer: a review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3511–3536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrams SA, Griffin IJ, Hawthorne KM, et al. Vitamin D receptor Fok1 polymorphisms affect calcium absorption, kinetics, and bone mineralization rates during puberty. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:945–953. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ames SK, Ellis KJ, Gunn SK, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene Fok1 polymorphism predicts calcium absorption and bone mineral density in children. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:740–746. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatzipapas C, Boikos S, Drosos GI, et al. Polymorphisms of the vitamin D receptor gene and stress fractures. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:635–640. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1216375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClung JP, Karl JP. Vitamin D and stress fracture: the contribution of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:365–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zmuda JM, Cauley JA, Ferrell RE. Molecular epidemiology of vitamin D receptor gene variants. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:203–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price DA, Fisher ND, Lansang MC, et al. Renal perfusion in blacks: alterations caused by insuppressibility of intrarenal renin with salt. Hypertension. 2002;40:186–189. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000024349.85680.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins PN, Hunt SC, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Angiotensinogen genotype affects renal and adrenal responses to angiotensin II in essential hypertension. Circulation. 2002;105:1921–1927. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014684.75359.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamarthi B, Williams JS, Williams GH. A mechanism for salt-sensitive hypertension: abnormal dietary sodium-mediated vascular response to angiotensin-II. J Hypertens. 2010 Mar 3; doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283375974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arabi A, El Rassi R, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Hypovitaminosis D in developing countries-prevalence, risk factors and outcomes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:550–561. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arai H, Miyamoto K, Taketani Y, et al. A vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in the translation initiation codon: effect on protein activity and relation to bone mineral density in Japanese women. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:915–921. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jurutka PW, Remus LS, Whitfield GK, et al. The polymorphic N terminus in human vitamin D receptor isoforms influences transcriptional activity by modulating interaction with transcription factor IIB. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:401–420. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colin EM, Weel AE, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Consequences of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms for growth inhibition of cultured human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;52:211–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.00909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross C, Krishnan AV, Malloy PJ, et al. The vitamin D receptor gene start codon polymorphism: a functional analysis of FokI variants. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1691–1699. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.11.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant FD, Mandel SJ, Brown EM, et al. Interrelationships between the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and calcium homeostatic systems. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:988–992. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.4.1400892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomaschitz A, Pilz S. Aldosterone to renin ratio--a reliable screening tool for primary aldosteronism? Horm Metab Res. 2010;42:382–391. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Zeeuw D, Agarwal R, Amdahl M, et al. Selective vitamin D receptor activation with paricalcitol for reduction of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes (VITAL study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1543–1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tripathi G, Sharma R, Sharma RK, et al. Vitamin D receptor genetic variants among patients with end-stage renal disease. Ren Fail. 2010;32:969–977. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.501934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]