Abstract

PURPOSE

The purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the experiences of living with severe heart failure (HF) from the perspective of the partner.

METHODS

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 partners of individual’s diagnosed with severe HF. Content analysis was performed to derive the main themes and sub-themes.

RESULTS

Three main themes were derived from the data: 1) My Experience of HF in My Loved One, 2) Experience with Healthcare Providers, and the 3) Patient’s Experience of HF as Perceived by the Partner.

CONCLUSION

The severity of the patient’s disease limited the partner’s lifestyle, resulting in social isolation and difficulties in planning for the future for both the patient and the partner. The partner’s were unprepared to manage the disease burden at home without consistent information and assistance by healthcare providers. Additionally, end of life planning was neither encouraged by the healthcare provider nor embraced by the patient or partner.

Heart failure (HF) is a debilitating chronic illness characterized by frequent exacerbations in symptoms that result in hospitalizations, high mortality rates, and impaired quality of life (QOL).1 In 2005, 5.3 million Americans had HF, and approximately 550,000 new cases are diagnosed each year.1 HF is the only major cardiovascular disease where incidence and prevalence continues to increase each year in the U.S.1 The treatment of HF requires complex medication and dietary regimens to manage the disabling symptoms: fatigue, shortness of breath, weight gain, depression, and pain.2

Self-care for HF often requires the assistance of other persons to enable the patient to manage the demands of the illness at home. The involvement of a key person, often the significant other, enables the HF patient to manage the medical regimen at home and to maintain good life quality. A recent study by Hwang and colleagues, found that partners of HF patients were more likely to provide personal care and emotional care compared to partners of healthy individuals after controlling for their age.3 Yet, little is understood about the impact of caring for the HF patient on the physical and mental health of caregivers. Given the complexity of HF management, it is expected that a large and growing number of family caregivers are currently involved in HF management at home. In this paper, the term partner is used when describing the spouse, significant other, or person living in an intimate relationship with the patient who has HF. The term patient is used when discussing the individual with HF.

Having a family member with HF affects the quality of life (QOL) of the partner.4 Multiple reports indicate that QOL, anxiety, caregiver’s health and depression can worsen when caring for a patient with HF.4–9 Issues that contribute to caregiver strain, distress, and decreased QOL include the constant physical and emotional challenge of balancing caring for the patient and managing household responsibilities while the partner deals with his or her own health issues, sleep disturbances, social isolation associated with caregiving, and the emotional toll of watching the patient’s condition worsen.9–14

Previous studies have described the experience of living with a person with HF. Aldred and colleagues described the effects of HF on four major aspects of life: everyday schedules, relationships, professional support, and concerns about the future.11 Both patients and their partners described the impossibility in planning daily activities due to the unpredictability of symptoms.11 Luttik and colleagues also reported partners of HF patients experienced significant changes in everyday life including daily tasks, personal activities, and joint activities with the patient. Partners reported difficulties with communication between themselves and health care providers, especially in times of crisis.13

In the studies that have described family burdens in HF caregiving, none have focused on patients with advanced or severe HF. The purpose of this qualitative descriptive study is to describe living with a person who had New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification 3 or 4 from the perspective of the partner. NYHA class 3 patients are comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary physical activity causes fatigue, dyspnea, palpitations, or angina.15 NYHA class 4 patients have symptoms at rest and any physical activity results in increased discomfort.15 This study uniquely focused on how the partners viewed the illness including their experience of the patient dealing with the symptoms, treatment, and progression, as well as the discussion of the partners’ needs to better cope with and help manage the illness. Additionally, the study attempted to describe the role of advance directives on end of life care as perceived by the partner.

METHODS

Design

This analysis was conducted as part of a larger study aimed at describing the understanding of and planning for the future by patients, partners, and providers in severe HF or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This paper contains the results of the partner’s experiences in living with a patient who had HF. The results from the interviews with the patients have been previous reported.16 A total of 14 interviews with partners were conducted between 2003–2004. Thirteen interviews were conducted over the phone and one interview was conducted in a private conference room. A semi-structured interview guide was used to address the partner’s experiences while living with a patient with HF. All interviews were audio tape-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using a content analysis approach. A qualitative descriptive naturalistic inquiry approach was used to identify experiences of living with HF from the perspective of the partner.18 This approach uses content analysis and comparison between and among concepts to derive results that reflect the experiences of those individuals participating in the study. Constant comparison was made between and within interviews.

Sample

A convenience sample of partner’s of person’s living with NYHA FC HF 3 or 4 were approached for participation in the study after the patient agreed to participate. Patient’s were approached to participate in the outpatient setting by their cardiology providers if they met the following criteria: 1) NYHA class 3 or 4 as determined by the provider, 2) no other life threatening disease, 3) not a heart transplant candidate, 4) age > 21 years, and 5) able to read, write, and understand English. Exclusion criteria were: 1) life expectancy < 1 year from other co-morbid illness, and 2) significant cognitive impairment at baseline screening. Twenty-four (24) patients agreed to participate in the study, and 16 had a partner. From these 16 partners, 14 agreed to complete an in-depth interview. Of the two partners who chose not to participate, one had a husband that was transitioning to hospice care and the other partner could not be reached. The inclusion criteria for partners were: 1) significant other or intimate partner living with a patient who agreed to participate in the study, 2) age > 21 years, and 3) able to read, write, and understand English.

Procedures

Patient participants were recruited from two medical centers in the Pacific Northwest. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the academic institution and the participating medical centers. All participants provided written informed consent before study procedures began. Only the research team had access to information regarding the partner interviews. Telephone interviews were conducted with the partner in their own home or in a private location where the interviews were not overheard by others.

After the patient gave informed consent to participate in the patient study, the partner was approached for participation. The Short Blessed cognitive screening tool was administered during telephone screening to determine baseline cognitive ability. Scores greater than 10 indicate severe cognitive dysfunction, and excluded partners from participating in the study.17 A semi-structured guide was used that addressed the following topical areas: 1) understanding of the prognosis of HF in the patient, 2) the patient’s experience with HF, 3) the future, 4) experiences with healthcare providers, and 5) decisions made with the patient regarding end-of-life preparation. All interviews were conducted by one research study nurse (GP).

Analysis

Validity and reliability (trustworthiness) of the data were addressed using criteria from Lincoln and Guba: 1) credibility, 2) dependability, and 3) confirmability.18 The first stage of the analysis was conducted by listening to tapes and reading transcripts and observational notes. Next, categories of importance were formulated, based on the issues and ideas identified. Every transcript was then read again and coded using a systematic scheme. An inductive methodology was used for content analysis of the transcribed data. Using the actual words, phrases, and sentences of the partners, codes were developed and constructed. Transcriptions were verified for accuracy by comparing the transcription to the tape-recorded interviews. All interviews were tape recorded, transcribed, and entered into Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing (NUD*IST) version QRS N6 for organizing the analysis. Demographic data were analyzed using SPSS v.14.0. Line numbers were used to aid future re-visitation with the transcript. Connected themes were highlighted so their link was explicit. Care was taken that themes “fit” the data and were an accurate reflection of the interview discussion.

Validity and accuracy were addressed by collecting data in the same way, and using the same semi-structured format. Initial coding of the data was conducted independently by a coder, then reliability checks were conducted between one investigator and another coder. During the final phases of analysis, study participants were asked to read and provide feedback on the study findings for validity reasons. Discrepancies were reviewed by the investigators and discussed until consensus was reached in the final coding of the data. Final categories were agreed upon by two investigators in the study.

RESULTS

Demographics

The sample consisted of 14 partners with a mean age of 64.85 ± 7.68 years. The majority of partners were married (92.9%) to the patient, Caucasian (92.9%), and women (78.6%). Half of the partners were retired from full-time work (50%), whereas the remainder worked either part-time (28.6%) or full-time (14.3%). The highest level of education for the majority of the partners was high school (57.1%), with a quarter of the individuals having some college or completed college (28.6%). Over half of the partners reported no health problems of their own (57.1%). See Table 1.

Table 1.

HF Partner Demographics N=14 participants

| Variable | Value | range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age | M ± SD | 64.85 ± 7.68 | 51–76 |

| gender | N (%) | 11 female (78.6%) | |

| 3 male (21.4%) | |||

| ethnicity | N (%) | 13 (92.9%) Caucasian | |

| 1 (7.1% Asian/Pacific Islander | |||

| Shorted BLESSED score | M ± SD | 2 ± 2.6 | 0–8 |

| marital status | N (%) | 13 (92.9%) married | |

| 1 (7.1%) partner, not living together | |||

| education | N (%) | 8 (57.1%) finish high school | |

| 2 (14.3%) finish vocational education | |||

| 2 (14.3%) some college | |||

| 2 (14.3%) finish college | |||

| employment | N (%) | 2 (14.3%) full-time employment | |

| 4 (28.6%) part-time employment | |||

| 7 (50%) retired | |||

| 1 (7.1%) housewife | |||

| partner health problems | N (%) | 8 (57.1%) no problem | |

| 3 (21.4%) diabetes | |||

| 3 (21.4%) other – stroke/TIA, HTN, pancreatitis |

TIA = transient ischemic attack, HTN = hypertension.

Patient’s had a mean age of 68 ± 7.1 years. Most of the patients were Caucasian (83%) men (88%). They had been living with HF for an average of 8.0 ± 7.9 years. The patient’s averaged 1.5 ± 1.1 hospitalizations during the past year (range 0–5), had an average ejection fraction of 29% ± 18, with NYHA FC 3 symptoms (96%). All of the patients had an implantable cardoverter defibrillator (ICD) for the prevention of sudden cardiac arrest.

Major Themes

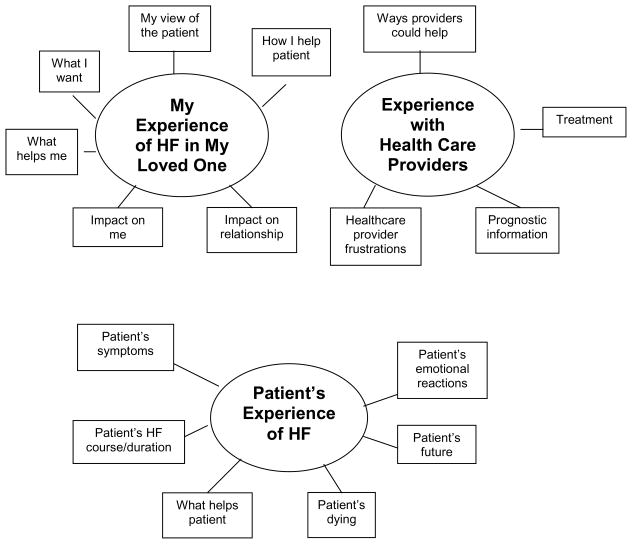

Three major themes, “My Experience of HF In My Loved One”, “Experience with Healthcare Providers”, and the “Patient’s Experience of HF as Perceived by the Partner” (Figure 1), were derived from the data. These included experiences from the diagnosis of the disease up to the death of the patient, the daily activities of the couple, the changes that occurred within the relationship between the patient and the partner, the treatment and progression of the disease, and the end of life decisions addressed by the couple.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework of HF Partners “Living with HF”

My Experience of HF in My Loved One

My Experience of HF in My Loved One described the impact of HF on the partner and the impact on the relationship from the partner’s perspective. My Experiences of HF in My Loved One was the most common theme derived from the interviews. The sub-themes in this category included: impact on relationship, impact on me, what helps me, what I want, my view of the patient, and how I help the patient. The most frequently discussed sub-themes, impact on our relationship, impact on me, and what helps me, are described in greater detail below.

Impact on relationship

Primarily, partners said that HF caused them to make adaptations in the relationship because the patient was not able to do much physically. Some of these adaptations included going out of the house less often for social activities, being more flexible in dealing with daily ups and downs, focusing on day-to-day experiences, and taking the time to work through difficulties. Partners realized the stress and challenges they faced each day, but they reported that they adjusted and “stuck together through thick and thin.”

Partners realized that the patient could no longer carry on life as they once knew it. As the demands placed on them by the patient increased, often their roles in their relationship shifted and significant lifestyle changes occurred. One partner said, “It’s very hard to be able to do things together. That, and things that we wanted to do we can’t do.” The partners had to take over some, if not all of the previous “duties” of the patient, including housework, yard work, and bill paying. Many partners felt isolated as a result of the illness and the changes it caused in the relationship.

For the majority of partners, communication about HF was a struggle. The person with HF was thought to not fully share the negative effects of their disease with their partner, perhaps to shelter them from the true seriousness of their condition. Talk about the future and discussions about end of life issues were generally avoided. When discussing communication, a partner said, “Well, it’s kind of hard in a way because there are different things that we really need to probably talk about, and it isn’t – it’s just kind of pushed aside. I don’t know. That’s how I feel.” However, a few partners shared how the disease improved overall communication in the relationship. One partner stated how the disease caused her to be more honest with her partner and vice versa.

Impact on me

The most prominent effects on partners’ were in emotional responses to the patient’s illness. The partners faced the challenges of maintaining hope while dealing with despair. Partners felt the patient did not understand the impact HF had on them. Partners were concerned about how to maintain the patients’ hope. One partner talked about the overall emotional impact of the disease and said, “I just feel overwhelmed sometimes.” Another partner discussed how quickly her mood and emotions changed, “I just – I go along and I can be fine, and then you change something on me or throw something else at me, and then, that’s when I kinda have a little bit of a meltdown.” Most partners spoke of how their lifestyle had changed significantly and how they had to sell many of the things they used to enjoy as a couple, such as a private airplane or mobile home.

What helps me

Partners described that what helped them deal with HF was having faith, a support system or someone to talk to, and having a positive attitude. Partners realized the importance of taking time for themselves and being able to step away from the challenges and demands of the disease. Work and hobbies, if the partner could find time, were extremely helpful. One partner said, “I love what I do. I enjoy the work tremendously. So work for me I think, has been my outlet. I think I would find it much harder to deal with if I were home all the time.”

Experience with Healthcare Providers

The second major theme, Experience with Healthcare Providers, described the partners’ frustrations with healthcare providers, the treatments and prognostic information they received, and ways healthcare providers could be more helpful. This category provides hints to health care providers about how they can help partners with caregiving demands.

Treatment

Partners talked extensively about the treatment options for patients, including medications, procedures, the ICD, hospitalization, and issues with the patient’s non-adherence to the health care plan. Although the medications were helpful, the majority of partners focused on side effects, cost, and the caregiving regime required to keep the patient symptom free. Many HF medications resulted in the patient feeling nauseated, groggy, weak, sleepless, and occasionally incontinent. One partner discussed how grateful he was for all of the therapies, “I am very thankful for all of that [the treatments]…” because it helped to keep him alive.”

Prognostic information

The majority of partners reported that providers gave very little prognostic information to the patient or to them. Partner’s felt uninformed and “left in the dark” about the patient’s future. One partner said, “They have never just sat down and – and had a talk about what this means and what the future might hold, what to look out for or what to expect.” Partners who did not receive life expectancy information felt that it would have been helpful in getting the patient’s affairs in order and to prepare for the future. However, most of the partners who did receive prognostic information did not find it to be particularly helpful. Often the patient out lived the life expectancy predicted by the provider, leaving both the patient and partner feeling unsure about the future. Nonetheless, a couple of partners spoke of how the life expectancy information provided hope and was useful in planning for the future.

Ways providers could help

Partners desired more information from healthcare providers in several areas: 1) how to treat symptoms, 2) where partners could find more information about HF, and 3) how HF progresses as an illness, including expectations about the future. Some partners felt that the brochures and handouts from healthcare providers were helpful, but many did their own research into the disease and its progression because they felt that the information they received was inadequate. A partner suggested, “It might be helpful if they would do more counseling, though. Give us more of an idea of what’s going to happen – not just what the immediate illness is doing and taking care of that – but as far as the future of it and how it might progress.”

Frustrations with healthcare providers

The most common frustration expressed by partners about health care providers was a lack of information. When giving information to the patient and partner, the provider used professional jargon that the patient and partner did not understand. A partner gave an example of this and described her confusion, “I mean, they tell me now that his heart function is like 15%. I don’t know what that means. Does that mean that he’s in a relatively tenuous position? What does it mean? I don’t know?” Providers conveyed a sense that they were busy, and partners said they had few opportunities to ask questions and to get them answered in an understandable manner. Some partners felt a “lack of caring” by the provider. Providers did not seem to notice how life altering a diagnosis of HF was for the patient and partner. It was perceived by some partners that providers were not interested in the patient as a whole and focused solely on symptoms and medications. One partner said, “Doctors [do] not realize that one day your life is just normal and then this comes and smashes everything to bits, you know – and there are so many questions.” Another partner commented, “It doesn’t seem like they [the doctors] realize it changes your life totally, and you just feel like you’re left out in left field to figure it out by yourself.”

Patient’s Experience of HF as Perceived by Partners

The last of the three major themes is a description of the partners’ view of the patient’s experience of HF. This theme focused on the patient’s symptoms, course/duration of the illness, dying, and the patient’s future.

Patient Symptoms

Lack of energy, fatigue and difficulty breathing were the symptoms most frequently discussed by partners. These symptoms reduced or eliminated the patient’s ability to work, walk, travel, and engage in social events. One partner described her loved one as “almost non-functioning.” When discussing the patient’s symptoms, one partner said, “He was really getting weak and really – he couldn’t walk from his chair to the bathroom. We have a little tiny house, so it was probably about 20 feet, and he couldn’t go from his chair to the bathroom without really huffing and puffing – it was scary just to listen to him.” The struggle to breathe was also very distressing to partners. Partners were unsure of how to help with breathing difficulties or how to help the patient manage this symptom. One partner commented, “I couldn’t sleep because I was listening for him to make sure he was breathing.” A few partners acknowledged how symptoms of the disease made them view the patient differently. One partner said, “He [the patient] is not a normal healthy 62 year-old male.” Other partner said that she viewed her husband as “very fragile.”

HF Course/Duration

As part of HF course/duration, partners discussed the long trajectory of the HF illness. HF symptoms and disability became progressively worse with time, but consisted of several “ups and downs.” The partners spoke of times when the patient’s condition improved for a while, especially after an ICD was placed, and times when the patient’s condition worsened. There was a recognition that HF symptoms could be treated and managed but the disease would result in the death of the patient at some point. The course of HF illness was described as living day-to-day on a roller coaster that required constant adjustments in medications, plans, and life goals. A partner said, “Well, it’s just been a day-to-day basis because you never know. Some mornings he wakes up and can hardly breathe and he’s very short of breath. In fact, we just sort of forget about it because it doesn’t happen for quite a few months at a time, and then suddenly it’s there. So, it’s just – you never know.”

Patient’s Dying

Despite clear ideas by partners about the how the patient wanted to die, not all of the patients had completed advance directives. Many of the partners mentioned that they had not talked about death with the patient and that the patient did not have advance directives or a living will in place. From the view of the partners, some patients did not feel the need to have an advance directive because the patient wanted all possible measures taken to prolong their life if needed. Multiple partners mentioned how the patient wanted “everything” to keep them alive. Yet, other partners knew that the patient did not what extraordinary measures taken. Some partners knew the patient did not “want to be brought back,” “kept alive just by machinery”, or “put on a feeding tube.” However, many of these partners were uncertain if the patient had discussed advance directives options with their physician.

As previously mentioned, all the patients in this study had an ICD. Patients with ICDs and their partners face a unique set of end of life issues involving turning off the device at or around the time of death. Despite discussions of end of life issues in the interview, few of the partners expressed knowledge of these unique issues or had given serious consideration to how an ICD would change their plans for end of life care. Patient’s mentioned and partners believed that it was possible for the patient to “just slip away peacefully while sleeping”, without considering the presence of the ICD and how it could be managed at the end of life.

Patient’s Future

Partners hoped for the best in the future and an improvement in the condition of the patient. They hoped that the patient would live many more years and that a cure for HF could be found so they could return to their previous lifestyle. Often, the partners hoped that their loved one would live long enough to reach some anticipated family milestone or an important trip. Despite having a sense of hope about the future, it was also marked with uncertainty. Uncertainty produced by HF included not knowing how much time was left, not knowing what to expect each day, and difficulty in predicting how the patient would respond to future plans. Planning for the future was difficult because of frequently cancelled or changed plans due to the patient’s symptoms. One partner stated, “It’s very difficult to plan ahead. It’s hard to even plan a week ahead.”

In living with HF over time, some partners came to accept the disease and its effects on the patient. Some accepted the reality of the disease and worried less about the future, attempting to focus on the present and on the time they had remaining with the patient. The idea of “what’s going to happen is going to happen” was commonly repeated in the interviews.

DISCUSSION

In describing the experiences of partner’s who were living with a person with severe HF, we found that the majority of themes present in our findings are similar to the findings of previous studies of caregiving in HF. Heart failure results in significant changes in the everyday lives of partners. The relationship between the patient and the partner is impacted in role changes, communication issues, social isolation, physical and emotion toll of the disease, and uncertainty about the future. The need for information and guidance from healthcare providers in severe HF is very important to those caring for a loved one at home.

Many of the issues faced by caregivers of patients with HF are also encountered by caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and cancer. Multiple studies exploring the perspectives of family caregivers of patients with AD have identified role changes, caregiver burden, communication, support and resources, loss and grief, and guilt about nursing home placement to be the major issues.19–25 A recent study suggests that QOL in AD partners is lower than healthy elderly individuals and AD patients.25 Similarly to HF partners, AD partners often experience declines in their own health, both physical and mental, as a result of caregiver strain and burden.22–23

A recent review by Stenberg and colleagues identified the types of problems and burdens that family caregivers of cancer patients experienced during the patient’s illness. They described four main categories: 1) physical problems and QOL, 2) social problems and need for information, 3) responsibilities and impact on daily life and 4) emotional problems.26 Common problems of physical health included pain, sleep problems, fatigue, and other health problems. For the social problems, common themes were financial difficulties, work difficulties, role strain, isolation, and information needs. The impact of caregiving on daily life included direct and indirect care of the patient and changes in usual routine and lifestyle. Finally, emotional problems such as anxiety, depression, fear, uncertainty, hopelessness, helplessness, powerlessness, and emotional reactions to caring were found to be challenging.26 These major categories are consistent across both caregiver issues in both HF and AD.

Because there are similar issues faced by caregivers, perhaps interventions initially designed for one set of caregivers may be applied to or adapted for another group. For example, the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health II (REACH II) intervention has been shown to decrease caregiver burden and result in better self-reported health, sleep quality, physical and emotional health in AD caregivers.27 Similar interventions need to be developed to decrease caregiver burden and increase self-reported health for HF caregivers. More research to test interventions to enhance caregiver effectiveness and well being is needed in chronic HF care.

One of the goals of this study was to explore the partners’ perspective on future decisions making and end of life preparation. Due to the severity of illness in the patient sample, we expected to find a larger number of patients with advanced directives that had been completed, compared to studies involving patients with less severe HF. However, we discovered that most partners spent little if any time, discussing the future or making end of life decisions with the patient. Most patients and partners had an idea of a “best” death, yet had no advance directives in place to support the process of ensuring a comfortable death. This is consistent with other studies that have found that the use of palliative care services in patients with HF is low when compared with other chronic illnesses. 28 Additionally, only a few of the patients and their partners were aware of the unique end of life issues associated with deactivating the ICD near or at the time of death.

This study suggests that healthcare providers are not proactive about providing end of life information or encouraging discussions about these issues despite suggestions in published guidelines.29 Additionally, the majority of partners reported that receiving life expectancy information from health care providers regarding the long-term survival of the patient was not useful to them, and often scared or confused the patient.16 However, the problem may not be healthcare provides per se, but rather end of life planning approaches in general. Traditional approaches to end of life planning have multiple limitations. Fried and O’Leary conducted in-depth interviews with 64 caregivers appropriately six months after the patient’s death from advanced cancer, COPD or HF.30 Four common themes were present in the data: 1) the lack of availability of treatment options for certain patients, prompting patients and caregivers to consider broader end-of-life issues, 2) changes in preferences at the very end of an illness, 3) variability in patient and caregiver desire for and readiness to hear information about the patient’s illness, and 4) difficulties with patient–caregiver communication.30 The study suggests that novel approaches for end of life planning are still needed in severe HF.

Unlike other studies on HF, this study also provides a unique insight to the perspective of partners regarding the patient’s experiences with HF. Overall, the partners focused on four aspects of the patient’s experiences: symptoms, disease course/duration, dying, and the future. These were the most difficult to manage and deal with emotionally. In the future, these areas could be priorities for the development of family interventions to enhance adaptation of partners who are caring for a patient with advanced HF at home.

Recommendations to Healthcare Providers and Researchers

Partners suggested that better communication with providers in two specific areas could significantly improve HF care. These areas include avoiding the use of professional jargon or terminology and providing more information about all aspects of the disease including its treatment and progression. Additionally, partners believed that difficulties in communication between the family and the provider prevented the provider from fully understanding their struggles and challenges in attempting to care for the patient at home. The nature of this study makes it difficult to determine how communication breakdowns occurred. We are uncertain if healthcare providers were uncomfortable discussing the course and progression of HF, or if patients and partners had difficulty receiving or processing the information. Future research should address these communication difficulties, so that both patients and partners are fully informed and supported during advanced HF home care.

Partners suggested that interactions with health care providers could be improved by the expression of greater empathy toward family members and caregivers. We do not suggest that healthcare providers were inadequately expressing care or compassion, but rather this highlights differences in perception of the healthcare provider by the partners. Some of the partners wanted psychological support such as referrals or recommendations for support groups and information about the community resources available for the patient. When this information was not given, the partners often viewed the provider as not caring about the patient.

Finally, it is apparent from this study that partners are unaware of the end of life issues associated with an ICD. Healthcare providers must make communication about these issues a priority at the time of ICD implantation and especially when a HF patient’s condition worsens. The discussion about the need to deactivate the ICD near or at the time of death could serve as a transition to discuss overall end of life issues and needs.

Limitations

There are certain limitations to this study. The sample size was relatively small and homogenous, consisting primarily of Caucasian female partners of patients with severe HF. The results of the study may not be generalizable to the other ethnic groups in other parts of the country. Additionally, most of the patients of the partners were NYHA FC 3. Therefore, the findings could have been different if the patients of the partners were healthier (NYHA FC 1–2). However, the majority of themes discussed by the partners in this study were consistent with the findings of other HF studies and studies exploring caregiver issues in other disease states. The sample was drawn from patients who were receiving care at an academic based HF program with an active cardiac transplant service with an accompanying VA medical center. The type of usual and expected care in a medical center setting may not represent usual care of HF in the community.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the number of patient and partners dealing with the physical and emotional challenges of HF is increasing. This study provides a better understanding of the experiences of the partners and identified areas of treatment that can enhance quality of care received by patients with HF and their families. Further, the study identified various aspects of the patient-provider interaction as well as the partner-provider interactions, that warrant additional investigation to improve the experiences of partners of patients living with severe HF.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH, National Institute for Nursing Research, 5R21NR008764-02; NIH, National Institute for Nursing Research, 5T32NR007106-12

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christopher C. Imes, University of Washington School of Nursing.

Cynthia M. Dougherty, University of Washington School of Nursing, Nurse Practitioner, VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Gail Pyper, Seattle King County Public Health.

Mark D. Sullivan, University of Washington.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2008 update. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett SJ, Sauvé MJ. Cognitive deficits in patients with heart failure: A review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;18:219–42. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200307000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang B, Luttik ML, Dracup K, Jaarsma T. Family caregiving for patients with heart failures: Type of care provided and gender differences. J Cardiac Fail. 2010;16:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martensson J, Dracup K, Canary C, Fridlund B. Living with heart failure: Depression and quality of life in patients and spouses. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:460–7. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moser DK, Dracup K. Roles of spousal anxiety and depression in patient’s psychosocial recovery after a cardiac event. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:527–32. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000130493.80576.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooley PJ, Butler G, Howlett JG. The relationship of quality of life, depression, and caregiver burden in outpatients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11:303–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2005.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Veeger NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ. For better and for worse: Quality of life impaired in HF patients as well as in their partners. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung ML, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Rayens MK. Effects of depressive symptoms and anxiety on quality of life in patients with heart failure and their spouses: Testing dyadic dynamics using Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pressler SJ, Gradus-Prizlo I, Chubinski SD, Smith S, Wheeler S, Wu J, et al. Family caregiver outcomes in heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18:149–59. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmilovich SE. Burden and stress associated with spousal caregiving for individuals with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1994;9:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldred A, Gott M, Gariballa S. Advanced heart failure: Impact on older patients and informal carers. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:116–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakas T, Pressler SJ, Johnson EA, Nauser JA, Shaneyfelt T. Family caregiving in heart disease. Nurs Res. 2006;55:180–8. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luttik ML, Blaauwbroek A, Dijker A, Jaarsma T. Living with heart failure: Partner perspectives. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:131–7. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200703000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rausch MS, Baker K, Boomee J. Sleep disturbances in caregivers of patients with end-stage congestive heart failure: Part I – the problem. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:38–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2007.05818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of diseases of the heart and great vessels. 9. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown & Co; 1994. pp. 253–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty CM, Pyper GP, Au DH, Levy WC, Sullivan MD. Drifting in a shrinking future: living with advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;22:480–7. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000297384.36873.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lincoln Y, Guda E. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlin NJ, Bell PA, Noah JL. Long-term consequences of the Alzheimer’s caregiver role: A qualitative analysis. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2001;16:177–82. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winslow BW. Family caregivers’ experiences with community services: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2003;5:341–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farren CJ, Loukissa D, Perraud S, Paun O. Alzheimer’s disease caregiving information and skills. Part II: family caregiver issues and concerns. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:110–20. doi: 10.1002/nur.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu YF, Wykle M. Relationships between caregiver stress and self-care behaviors in response to symptoms. Clin Nurs Res. 2007;16:29–43. doi: 10.1177/1054773806295238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrara M, Langiano E, Di Brango T, De Vito E, Di Cioccio L, Bauco C. Prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression in with Alzheimer caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:93. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank JB. Evidence for grief as the major barrier faced by Alzheimer caregivers: A qualitative analysis. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;22:516–27. doi: 10.1177/1533317507307787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schölzel-Dorenbos CJ, Draskovic I, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Olde Rikkert MG. Quality of life and burden of spouses of Alzheimer disease patients. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:171–7. doi: 10.1097/wad.0b013e318190a260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of care for a patient with cancer. Psycholooncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliot AF, Burgio LD, Decoster J. Enhancing caregiver health: Finding from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health II intervention. Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:30–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodlin SJ, Kutner JS, Connor SR, Ryndes T, Houser J, Hauptman PJ. Hospice care for heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:525–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried TR, O’Leary JR. Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient- and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1602–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]