Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the level of formal training and perceived educational needs in palliative care of emergency medicine (EM) residents.

Methods

This descriptive study used a 16-question survey administered at weekly resident didactic sessions in 2008 to EM residency programs in New York City. Survey items asked residents to: (1) respond to Likert-scaled statements about the role of palliative care in the emergency department (ED); (2) quantify their level of formal training and personal comfort in symptom management, discussion of bad news and prognosis, legal issues, and withdrawing/withholding therapy; and (3) express their interest in future palliative care training.

Results

Of 228 total residents, 159 (70%) completed the survey. Of those surveyed, 50% completed some palliative care training before residency; 71.1% agreed or strongly agreed that palliative care was an important competence for an EM physician. However, only 24.3% reported having a “clear idea of the role of palliative care in EM.” The highest self-reported level of formal training was in the area of advanced directives or legal issues at the end of life; the lowest levels were in areas of patient management at the end of life. The highest level of self-reported comfort was in giving bad news and the lowest was in withholding/withdrawing therapy. A slight majority of residents (54%) showed positive interest in receiving future training in palliative care.

Conclusions

New York City EM residents reported palliative care as an important competency for emergency medicine physicians, yet also reported low levels of formal training in palliative care. The majority of residents surveyed favored additional training.

Introduction

Palliative care seeks to alleviate suffering while promoting quality of life. Its formal role in the emergency department (ED) is a developing field. The American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS) recognized hospice and palliative medicine as a subspecialty of emergency medicine (EM) in 2006.1 In 2007, the Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Emergency Medicine (EPEC-EM) program began to offer education targeted to EM professionals on how to apply palliative care techniques in the emergency setting.2 In addition, early initiation of palliative care services in the ED has become an increasing priority of the palliative medicine practitioner.3 It is frequently in the ED that trajectories for future patient disposition and goals of care are set.4 Furthermore, the majority of deaths occurring in the ED setting is preceded by a decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments.5 Incorporating a palliative care skill set will enhance a patient-centered model of ED care. Several areas that are already elements of routine EM practice have been identified as necessary to comprising this primary skill set, including: formulating prognosis, difficult communication with patients and families, pain and symptom management, withdrawing and withholding nonbeneficial treatments, and an understanding of ethical and legal issues.6

Physician-based perceptions have been cited as barriers to using palliative care services.7 The culture of EM—to rapidly diagnose and treat acute conditions—may further result in the contradictory embracing of high-intensity treatments and resistance to palliative and end-of-life care, thus providing a barrier to use.8 Nonetheless, regardless of whether sub-specialization is pursued, palliative care should be a basic competency for EM physicians. While there is a growing interest in palliative care training by EM faculty, with more than 35 residency programs having at least one faculty member who has completed training in EPEC-EM,9 the development of and need for a primary palliative care skill set during residency training is not well-established.10 It is not known how trainees in EM residency programs view palliative care education.

The objectives of this study were to characterize New York City EM residents' perceived educational needs for palliative care and to investigate the relationship between their formal level of training and comfort level with a recommended primary palliative care skill set. This study also sought to determine the level of interest in more formal training among surveyed residents.

Methods

This was a self-administered survey of post-graduate year (PGY)-1 through 3 and PGY-1 through 4 EM residency programs in New York City and surrounding boroughs, as identified by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Residency Catalog.11 All EM residency programs have weekly didactic educational sessions. The survey was administered to residents in attendance at weekly didactic sessions of participating programs between July 2, 2008 and December 14, 2008. Participation in the study was voluntary. Survey responses were identified only by study numbers. Demographic sheets were kept separately from survey responses to ensure respondent anonymity. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the investigators' institution.

The survey defined palliative care as “focusing on relieving suffering and achieving the best possible quality of life for patients and their family caregivers.”12 Participants were asked to respond to Likert-scaled statements about the role of palliative care in the ED, rank level of faculty support in palliative care, express interest for future training, and quantify level of formal training and personal comfort in: symptom management, discussion of bad news/prognosis, legal issues, and withdrawing/withholding therapy. Formal training was defined as workshops, lectures, and teaching experiences. Comfort level was defined as personal level of emotional comfort. Survey topics and palliative care primary skill set were based on previous studies on palliative care administered to residency programs in pediatrics and internal medicine.13,14

Descriptive analyses of survey results were completed. Likert-scaled responses (5-item) were translated into ordinal numbers. Analyses were completed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Means and standard deviations were reported. Differences in mean responses were compared using Student's t test and ANOVA for parametric data and Kruskal Wallis Test for nonparametric data. Analyses were stratified by respondent experiences, training, and sites to determine significant changes in perceptions in palliative care. Values of p ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. A copy of the survey administered is provided in Appendix A.

Results

Six of the 14 EM residency programs in the New York City metropolitan area (Manhattan, Brooklyn, or Long Island, NY) participated in the survey; of these programs, all report having palliative care services available and three had at least one EPEC-EM trained faculty member. Three out of six institutions had fellowship training programs in palliative care. Programs unable to participate either did not respond to at least two requests for permission to administer the survey (n = 6) or were unable to coordinate an opportunity for administering the surveys (n = 2) during the study period. Of participating programs, 159 out of 258 (70%) residents completed the survey; seven respondents were excluded due to participation in combined emergency medicine-internal medicine residencies. Thus, 152 (66%) of 228 total eligible residents were analyzed.

Experience and training

Response by PGY-level was as follows: PGY1 33.3% (N = 53), PGY2 28.3% (N = 45), PGY3 23.3% (N = 37), PGY4 10.7% (N = 17). Almost every PGY2–4 (97.8%) resident reported caring for a patient who died compared to 30.7% of PGY1 residents (p < 0.001). Similarly, 93.2% PGY2–4 residents cared for patients who were terminally ill, compared to 39.2% PGY1 residents (p < 0.001). Mean number of estimated patient deaths and terminally ill patients cared for increased by PGY level. Exposure to palliative care services, reported as the mean percent of patients who died or were terminally ill receiving palliative care, is listed by PGY in Table 1. Overall, 20.9% of patients who died and 34.6% of terminally ill patients were reported to have received palliative care services.

Table 1.

Reported Experiences with Death and Terminally Ill Patients by PGY

| Mean # of patient deaths experienced | Range # of patient deaths experienced | Mean % of patients who died receiving palliative care services | Mean # terminally ill patients experienced | Range # of terminally ill patients experienced | Mean % of terminally ill receiving palliative care services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10.2 ± 13.9 | 0–110 | 20.9% | 16.7 ± 24.8 | 0–150 | 34.6% |

| PGY1 | 1.7 ± 3.6 | 0–15 | 27.3% | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 0–10 | 33.9% |

| PGY2 | 9.9 ± 7.2 | 0–30 | 28.9% | 22.1 ± 21.6 | 0–100 | 34.9% |

| PGY3 | 20.1 ± 19.4 | 2–110 | 22.1% | 33.9 ± 35.8 | 0–150 | 42.4% |

| PGY4 | 16.5 ± 17.7 | 0–75 | 10.3% | 13.0 ± 13.3 | 0–40 | 51.8% |

Half of the PGY1–4 (50%) reported receiving palliative care training before residency training. Seventy-one percent of respondents reported being aware of palliative care consult services available at their institution. (All surveyed programs have such services available.) Nineteen percent of respondents reported being aware of screening protocols to identify patients for palliative care services.

Stratified analyses of residents having any exposure to palliative care services compared to none were performed. In caring for terminally ill patients, exposure to palliative care varied by post-graduate year (p = 0.037) and awareness of a palliative care consult service (p < 0.001). In caring for patients who died, exposure varied by institution (p = 0.003). Surveyed sites with faculty who had completed the EPEC-EM course were more likely to have residents report some exposure to palliative care services for these patients (p < 0.001).

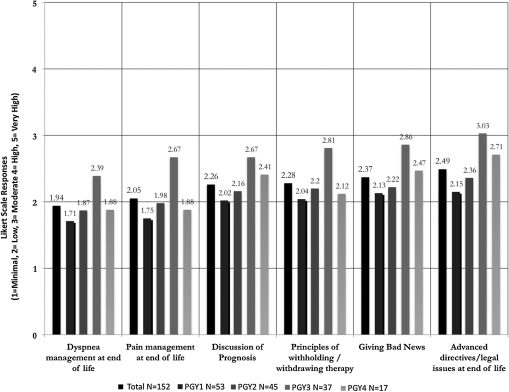

When rating their level of formal training in palliative care (1 = Minimal, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Very High), residents had most training in advanced directives/legal issues at the end of life, and least in dyspnea management at end of life. All levels ranged from the minimal to moderate level. This did not vary statistically by post-graduate year (PGY) or institution. A summary of the self-reported level of formal palliative care training results is found in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Level of formal training in palliative care topics by PGY.

Perceptions of palliative care and palliative training

Surveyed residents were asked to respond to statements with five-item Likert-scaled response choices (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree). To the statement, “Palliative care is an important competence for an emergency medicine physician,” the mean response was 3.78 ± .88. Seventy-one percent of responses agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. Overall, responses to this statement varied by institution (p = 0.020). However this difference was not seen when institutions were grouped according to having faculty who completed EPEC-EM training or having a fellowship program in palliative care. Responses did not vary by post-graduate year, exposure to palliative care, or the self-reporting of palliative care training before residency.

To the statement, “I have a clear idea of the role of palliative care in emergency medicine,” the mean response was 2.85 ± .98. Twenty-four percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. The response to this statement varied by institution (p = 0.028). However, this difference was not seen when institutions were grouped according to having faculty who completed EPEC-EM training or having a fellowship program in palliative care. There was a statistically significant difference in the response to this statement from residents whose average level of formal training in palliative care topics corresponded to a High or Very High level when compared to those whose average corresponded to a lower level of formal training (p < 0.001).

To the statement, “Calling a palliative care consult is giving up on the patient,” the mean response was 1.59 ± 0.72. Ninety-six percent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. To the statement, “Emergency medicine physicians are trained to save lives, not manage death,” the mean response was 2.24 ± 1.03. Sixty-eight percent of respondents Disagreed or Strongly Disagreed with this statement. The responses to these statements did not vary by training level, exposure to palliative care services, or by self-reporting of palliative care training before residency training.

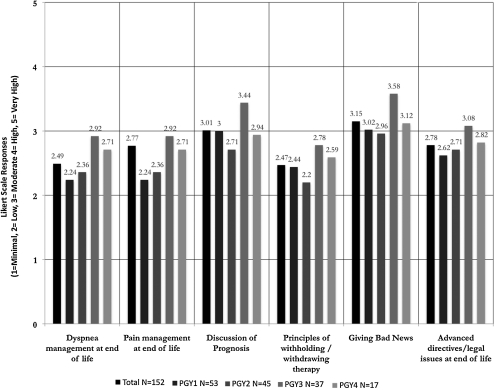

Residents' mean responses to comfort level in palliative care skill sets ranged from low to moderate (2.47–3.15) in all skill set topics. The lowest mean response to comfort level was in withholding/withdrawing therapy. There was no difference in response by training hospital. However, there was a statistically significant difference when mean responses were grouped by PGY in the areas of giving bad news (p = 0.009) and discussing prognosis (p = 0.010), as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Level of comfort in palliative care topics by PGY.

The mean response to the level of faculty support in end-of-life care was 2.95 ± 0.83, corresponding to a poor to adequate level. This did not vary by institution, but did vary by training level (p = 0.040). There was a statistically significant higher response to the reported level of faculty support by institutions that completed EPEC-EM training (p = 0.038).

Future directions in training

Most respondents (54.1%) agreed or strongly agreed they had an interest in further training in palliative care skill sets. Mean response was 3.48 ± 0.896. This result did not vary by PGY or training program. When provided with a rank-order list of future educational topics, residents expressed the most interest in further training in patient management at the end of life, principles in withholding/withdrawing therapy, and delivering bad news.

Discussion

The results of our survey provide insight into palliative care experiences and training for EM residents. We found that the overwhelming majority of residents had experiences with death and dying among patients during and before residency training, and a moderate proportion desired further training to develop palliative care skills. Residents recognized palliative care training as an important competence in EM training. In general, however, they did not have a clear idea of its role in the ED setting. This apparent discrepancy may be accounted for by the large amount of experience with death and dying many of the residents had, but the relatively low level of formal training in the surveyed areas constituting a primary palliative care skill set. The lack of understanding or recognition that palliative care elements are integral parts of emergency care may also account for only a moderate proportion of residents having a strong desire for additional training in palliative care.

Residents reported overall low levels of formal training, and this did not improve as they progressed with increasing PGY-level training. They had the most formal training in advanced directives/legal issues when compared to other categories. Relatively low levels, however, were reported in all categories. Higher comfort levels were reported than their corresponding formal training levels. Yet, overall, most comfort levels were reported as low. These results suggest that EM residents do not perceive their ability to provide palliative care as improving as they progress through their EM residency training. Fortunately, residents who reported high levels of formal training in palliative care topics felt they had a clearer understanding of the role of palliative care in emergency medicine.

Although residents reported caring for more patients at the end of life as they progressed in training, the percentage of those patients who received palliative care remained relatively constant. This illustrates a potential cohort of patients that could benefit from a more formalized palliative care skill set among emergency medicine providers.

Differences in exposure to palliative care reported by residents were institution-dependent, and having faculty trained in EPEC-EM appears to account for some component of the variability. Increased participation in this and similar initiatives may increase the use of palliative care practices in the ED.

It is interesting to note that, although residents reported high levels of experience with death and dying while concurrently expressing lower levels of comfort in handling such experiences, they only expressed a moderate desire for future training in palliative care. When compared to surveys of residents in other specialties (pediatrics, internal medicine), emergency medicine residents appear to have a lower priority for palliative care training.13,15 A significant contributor to these attitudes toward palliative care may stem from institutional factors. Survey results varied by site and by whether faculty were trained in EPEC-EM, indicating that the routine practice and culture of medical care at individual institutions significantly affected resident perceptions of palliative care exposure and training.

Comfort level with palliative care varied for institutions and programs with more formal palliative care training of emergency medicine residents. Residents at programs with EPEC-EM faculty felt they received more support with end-of-life care, but their perceptions of training in palliative care did not appear to be influenced by these faculty. This may indicate an even greater need for more intense palliative care training with EM faculty, or that the exposure and training in palliative care that residents receive by EPEC-EM faculty may be limited.

The emergency department and its clinical staff will increasingly encounter patients at the end of life. Emergency physicians, nurses, and practitioners have a unique opportunity to provide early evaluation and care to such patients that will affect subsequent care and outcomes. The assessment and care given to individuals who may benefit from palliative care at the beginning of their arrival to the hospital, while in the ED, will be pivotal for not only treating the acute symptoms that prompted the ED visit, but also for communicating desires, fears, and expectations patients and family members may have about goals of care. Both the National Institutes of Health and the American College of Emergency Physicians have established the importance of these needs.16–18

Emergency clinicians will require knowledge and skills to be comfortable and trained in identifying and providing palliative care for maximal benefit. The results of this study confirm that emergency physicians in training would not only embrace additional training, but seek such training. The time is now for emergency medicine to incorporate a primary palliative care skills set of symptom management, discussion of bad news/prognosis, legal issues, and withdrawing/withholding therapy, contains elements of routine EM practice.6

Limitations

Results of this study (focused on the New York City metropolitan and surrounding areas) may be limited and it may not be possible to generalize from these results to other institutions. The findings here are a preliminary investigation of regional palliative care experiences and perceptions of EM residents, and are hypothesis-generating. Actual levels of formal training and previous experiences for respondents were not determined, characterized, nor verified and only self-reported experiences and levels of formal training of individual residents were collected. While all study sites reported having palliative care services at their institutions and three of the six programs have palliative care fellowship training programs,19 the types of palliative care services available at the participating study sites are not known, nor the extent of access and interaction the ED staff have with the palliative care services at the study sites. Another limitation was the close-ended nature of our survey using Likert-scaled responses. Answer options were limited to those provided. For example, our rank-order list of educational topics did not include space to write in other options. Finally, resident preferences for types of palliative care educational interventions were not assessed by this survey.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that clinical exposure to patients at the end of life is occurring throughout EM training. The perceived level of training and comfort with palliative care skills, however, is lacking. Residents recognize the importance of a palliative care competence and the majority has expressed an interest in greater formal training in palliative care topics. Such an educational focus must expand beyond discussion of legal issues at the end of life into areas of palliative care patient management. Educational interventions, such as the train-the-trainer model, may be further used by and disseminated to residents by faculty.

Appendix A. Palliative Care Survey

| Your replies will remain strictly anonymous. |

|---|

| There is no means of linking replies to any information identifying the respondents. |

| For the purpose of this survey, please use the following definition of palliative care: |

| “Palliative care focuses on relieving suffering and achieving the best possible quality of life for patients and their family caregivers.” |

Experiences:

1. Please circle your level of training: PGY1 PGY2 PGY3 PGY4

-

2. My current training hospital is_______________________

There is a palliative care consultation service available: YES | NO

-

3a. During your residency, how many patients have died while you were caring for them:

Please indicate #: _____

-

3b. If you answered that palliative care consultation service is available at your hospital, of those who died, how many of these were given palliative care services:

Please indicate #: _____

-

4a. During your residency, how many terminally ill patients have you cared for in a meaningful way:

Please indicate #: _____

-

4b. Of those patients, how many were given palliative care services:

Please indicate #: _____

5. I received palliative care training before residency: YES | NO

6. I am aware of a screening protocol to identify patients best served by palliative care: YES | NO

Perceptions:

-

1. Palliative care is an important competence for an emergency medicine physician.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

-

2. Calling a palliative care consult is giving up on the patient.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

-

3. I have a clear idea of the role of palliative care in emergency medicine.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

-

4. Emergency medicine physicians are trained to save lives and not to manage death.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree5 = Strongly Agree

Training:

-

1. Please rate the level of FORMAL TRAINING (workshops, lectures, teaching) you have received during residency:

1 = Minimal 2 = Low 3 = Moderate 4 = High 5 = Very High

For the following topics:

| Giving bad news | _________ |

| Discussion of prognosis | _________ |

| Pain management at end of life | _________ |

| Dyspnea management at end of life | _________ |

| Advanced directives/legal issues at end of life | _________ |

| Principles of withholding/withdrawing therapy | _________ |

-

2. Please rate the level of COMFORT (personal level of emotional comfort) you have:

1 = Minimal 2 = Low 3 = Moderate 4 = High 5 = Very High

For the following topics:

| Giving bad news | _________ |

| Discussion of prognosis | _________ |

| Pain management at end of life | _________ |

| Dyspnea management at end of life | _________ |

| Advance directives/legal issues at end of life | _________ |

| Principles of withholding/withdrawing therapy | _________ |

-

3. Faculty precepting in end-of-life care:

1 = Very Poor 2 = Poor 3 = Adequate 4 = Good 5 = Very Good

-

4. Faculty support in end-of-life care training:

1 = Very Poor 2 = Poor 3 = Adequate 4 = Good 5 = Very Good

Future Directions:

-

1. I would like more palliative care training during residency.

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

2. Rank the following palliative care topics (A–E) in order of preference for additional education (1–5)

A. patient management at end of life

B. identifying patients appropriate for palliative care

C. legal issues at end of life

D. withholding/withdrawing therapy

-

E. delivering bad news

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR TIME AND PARTICIPATION.

PLEASE USE THE SPACE BELOW FOR ANY COMMENTS:

Acknowledgments

Nicholas Meo was supported by a Medical Student Training on Aging Research summer program award from the American Federation on Aging Research (AFAR). Ula Hwang is supported by a National Institute on Aging (NIA) K23 career development award (K23 AG031218). R. Sean Morrison is supported by a NIA K24 mid-career mentoring award (K24 AG022345).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist and authors maintained full independence during the conduct of this study.

References

- 1.2002 Annual Report and Reference Handbook. Evanston, IL: American Board of Medical Specialties–Research and Education Foundation; 2002. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuel LL, editor; Quest T, editor. The Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care for Emergency Medicine [CD-ROM] 2008. ©.

- 3.Meier DE. Beresford L. Fast response is key to partnering with the emergency department. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:641–645. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamba S. Mosenthal AC. Hospice, Palliative Medicine: A novel subspecialty of emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2010 May 22; doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.04.010. [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeConte P. Riochet D. Batard E. Volteau C. Giraudeau B. Arnaudet I. Labastire L. Levraut J. Thys F. Lauque D. Piva C. Schmidt J. Trewick D. Potel G. Death in emergency departments: A multicenter cross-sectional survey with analysis of withholding and withdrawing support. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1800-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quest TE. Marco C. Derse AR. Hospice and Palliative Medicine: New Subspecialty, New Opportunities. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez KL. Barnato AE. Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:99–110. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shears RM. Emergency physicians' role in end-of-life care. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;7:539–559. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care for Emergency Medicine (EPEC-EM) The EPEC Project. 2009. www.epec.net/EPEC/Webpages/epecem.cfm. [Apr 11;2009 ]. www.epec.net/EPEC/Webpages/epecem.cfm ©.

- 10.Chan GK. End-of-life and palliative care in the emergency department: A call for research, education, policy, and improved practice in this frontier area. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Residency catalog. 2008. www.saem.org/saemdnn/Home/Communities/MedicalStudents/ResidencyCatalog/tabid/6 80/Default.aspx. [Jul 1;2008 ]. www.saem.org/saemdnn/Home/Communities/MedicalStudents/ResidencyCatalog/tabid/6 80/Default.aspx ©.

- 12.Meier DE. When pain and suffering do not require a prognosis: Working toward a meaningful hospital-hospice partnership. J Palliat Med. 2002;6:109–115. doi: 10.1089/10966210360510226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolarik RC. Walker G. Arnold RM. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949–1954. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz C. Goulet JL. Gorski V. Selwyn PA. Medical Residents' Perceptions of End-of-life Care Training at a Large Urban Teaching Hospital. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:37–44. doi: 10.1089/10966210360510109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroder C. Heyland D. Jiang X. Rocker G. Dodek P. Educating medical residents in end-of-life care: Insights from a multicenter survey. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:459–470. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beemath A. Zalenski RJ. Palliative emergency medicine: Resuscitating comfort care? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Emergency Physicians. Ethical issues in emergency department care at the end of life. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:302–303. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health: The NIA State-of-the-Science Conference on Improving End-of-Life Care statement. 2004. http://consensus.hin.gov/2004/2004EndOfLifeCareSOS24pdf.pdf. [Aug 16;2010 ]. http://consensus.hin.gov/2004/2004EndOfLifeCareSOS24pdf.pdf

- 19.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Fellowship Program Directory. www.aahpm.org/fellowship/default/fellowshipdirectory.html. [Oct 28;2010 ]. www.aahpm.org/fellowship/default/fellowshipdirectory.html [DOI] [PubMed]