Abstract

Transgenesis enables the elucidation of gene function; however, constant transgene expression is not always desired. The tetracycline responsive system was devised to turn on and off transgene expression at will. It has two components: a doxycycline controlled transactivator (TA) and an inducible expression cassette. Integration of these transgenes requires two transfection steps usually accomplished by sequential random integration. Unfortunately, random integration can be problematic due to chromatin position effects, integration of variable transgene units and mutation at the integration site. Therefore, targeted transgenesis and knockin were developed to target the TA and the inducible expression cassette to a specific location, but these approaches can be costly in time, labor and money. Here we describe a one-step Cre-mediated knockin system in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells that positions the TA and inducible expression cassette to a single location. Using this system, we show doxycycline-dependent regulation of eGFP at the DNA topoisomerase 3β (Top3β) promoter. Since Cre-mediated recombination is used in lieu of gene targeting, this system is fast and efficient.

Keywords: knockin; gene targeting; inducible expression, Cre/loxP

Constant transgene expression is not always desirable; therefore, the tetracycline responsive system was developed to regulate transgene expression. It is based on the Tn10-specific tetracycline-resistance operon found in Escherichia coli (Hillen and Berens, 1994) and has two basic components. One component is a tetracycline-controlled transactivator (TA) (Gossen et al., 1995) and the other component is a TA-inducible expression cassette with a nonfunctional promoter. This promoter contains a series of eight tet operator (tetO) sequences immediately upstream of a minimal CMV promoter, called tetO-mCMV. Transcription is induced after the TA binds to the tetO sequences. The investigator controls transcription with doxycycline (dox), a tetracycline derivative that binds the TA to regulate activity. Thus, the investigator controls transgene expression with dox.

Both the TA and the inducible expression cassette must be integrated into cells by sequential rounds of random integration, targeted transgenesis or knockin. Random transgene integration can be problematic due to variable transgene copy number (Sandgren et al., 1991), epigenetic promoter silencing (al-Shawi et al., 1990), and mutagenesis (Covarrubias et al., 1986). To avoid these problems, targeted transgenesis (Jasin et al., 1996; Vivian et al., 1999) and knockin (Hanks et al., 1995; Shin et al., 1999) were developed. For targeted transgenesis, a transgene is targeted to a specific location. This transgene is a complete expression cassette with its own promoter and polyadenylation sequences. For knockin, a cDNA is targeted directly to an endogenous promoter. Targeted transgenesis and knockin resolve the problems associated with random transgenesis yet they can be costly in labor, time and money since each project requires the generation of a new targeting vector and targeted cells.

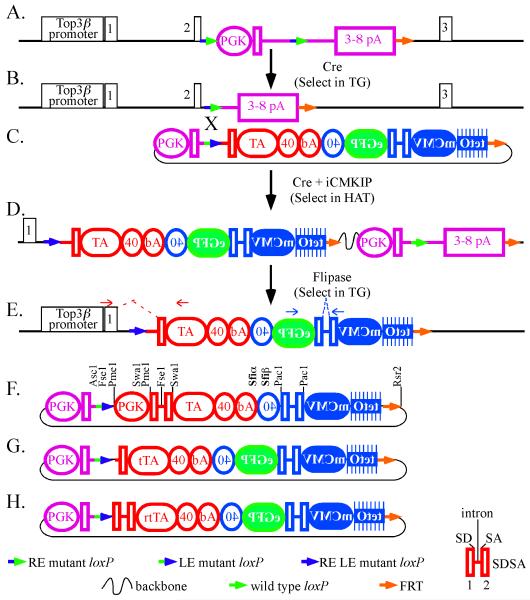

To maximize knockin efficiency, we developed a Cre-mediated protocol to knockin cDNAs adjacent to a specific promoter with high efficiency (Kim et al., 2008); here, we have adapted this protocol to accommodate the tetracycline responsive system. Previously, we targeted the Top3β gene using a floxed miniHPRT selection cassette (Holcomb et al., 2007); miniHPRT is well suited for this strategy since one can select for either the presence or absence of function in HAT (hypoxanthine, aminopterin, thymidine) or TG (6-thioguanine), respectively. Upon gene targeting, floxed miniHPRT replaced the Top3β initiating ATG in exon 2 (the first coding exon) (Fig. 1A). These cells were selected in HAT and HAT resistant clones were screened for targeting using PCR (Holcomb et al., 2007). Then Cre-recombinase removed the 5′ half of miniHPRT by virtue of RE mutant loxPs (Araki et al., 1997) positioned 5′ to miniHPRT and within its intron (Kim et al., 2008). These cells were selected in TG and PCR confirmed Cre-mediated deletion. These are the parental cells used for knockin; thus, they only have to be produced once (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Knockin of the iCMKIP to Top3β. (a) The Top3β gene after gene targeting; miniHPRT replaced the 3′ half of Top3β exon 2 (removes initiation ATG). miniHPRT (purple) contains a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter (Adra et al., 1987), HPRT exons 1+2 and HPRT exons 1-8, separated by an intron. An RE mutant loxP (blue green arrow) is 5′ to the PGK promoter and in the intron. (b) The 5′ half of miniHPRT was removed with Cre-recombinase. Select in TG, screen by PCR as described (Kim et al., 2008). (c) The iCMKIP composed of 6 parts:1) the 5′ half of miniHPRT (purple) to restore miniHPRT and HAT resistance upon Cre-mediated recombination, 2) a LE mutant loxP (green blue arrow) (Araki et al., 1997) for Cre-mediated recombination, 3) the TA (red), 4) the inducible expression cassette (blue) in reverse orientation to the TA, 5) eGFP (green) and 6) FRT (orange arrow) (Schaft et al., 2001). (d) Cre-mediated integration of iCMKIP. (e) FLP-mediated removal of miniHPRT. Select in TG and screen by PCR as described (Kim et al., 2008). Red and blue arrows show the oligonucleotide primers used to detect the Top3β exon1 + SDSA exon 2 + TA transcript and the SDSA exon 1 + SDSA exon 2 + eGFP fusion transcript, respectively. (f) The parental iCMKIP. The 5′ half of miniHPRT with the PGK promoter and exons 1+2 (purple). An LE mutant loxP (green blue arrow). The TA (red) contains a PGK, human α-globin splicing sequences (McCullough and Berget, 1997) with both a splice acceptor and splice donor separated by a small intron (with an Fse1 site), SV40 (40) and bovine growth hormone (bA) (Pfarr et al., 1986) polyadenylation sequences. The inducible expression cassette contains an inducible promoter with eight tetO sequences and the mCMV promoter (tetO-mCMV) and the SDSA sequences (without an Fse1 site). It shares polyadenylation sequences with the TA. (g) The tTA iCMKIP. The PGK promoter in TA and the splice donor sequences were removed with Fse1 and eGFP was cloned into the Sfi1 sites. (h) The rtTA iCMKIP. The PGK promoter was removed with Pme1 and eGFP was cloned into the Sfi1 sites.

The next step is to knockin the TA and inducible expression cassette adjacent to the Top3β promoter (Fig. 1C). To adapt our knockin procedure for the tetracycline responsive system, we designed a parental inducible Cre-mediated Knockin plasmid (iCMKIP) that contains six basic components: 1) the 5′ half of miniHPRT (Fig. 1C, purple) to restore miniHPRT and HAT resistance upon Cre-mediated recombination, 2) a LE mutant loxP (Fig. 1C, green blue arrow) (Araki et al., 1997) for Cre-mediated recombination, 3) the TA (Fig. 1C, red), 4) the inducible expression cassette (Fig. 1C, blue) in reverse orientation to the TA, 5) a multiple cloning site designed for cloning in the cDNA of interest, in this case eGFP (Fig. 1C, green) and 6) a FRT site (Fig. 1C, orange arrow) (Schaft et al., 2001). Upon transient expression of Cre recombinase the iCMKIP will integrate into the Top3β gene. After correct integration the TA will be adjacent to the Top3β promoter and miniHPRT will be restored to enable survival in HAT (Fig. 1D). Due to the stringent selection, all HAT resistant colonies are correct as confirmed by PCR (Kim et al., 2008). As a final, but optional step, FLP-mediated recombination will remove miniHPRT, plasmid backbone and wild type loxP; thus, miniHPRT may be used again (Fig. 1E). If this step is performed, then cells would be selected in TG and screened by PCR as previously described (Kim et al., 2008); however, this optional step was not performed here. Due to duel selection every step is selectable and highly efficient.

There are special features to the iCMKIP that maximize its utility (Fig. 1F). 1) We incorporated human α-globin splicing sequences (McCullough and Berget, 1997) with both a splice donor and splice acceptor (SDSA) separated by a small intron (Fig. 1E); the splice acceptor sequences are capable of trapping the splice donor from Top3β exon 1 which is critical for TA expression (Fig. 1E, red dotted line). In addition, SDSA sequences are positioned between the tetO-mCMV promoter and eGFP cDNA so that RT-PCR can identify a spliced transcript to verify eGFP transcription (Fig. 1E, blue dotted line). 2) We use mutant loxPs (Araki et al., 1997): RE mutant loxPs in miniHPRT and a LE mutant loxP in iCMKIP such that after Cre-mediated knockin a double RE LE mutant loxP and a wild type loxP remain; however, the wild type loxP will be removed after FLP-mediated deletion of miniHPRT at the final step. Theoretically the double mutant loxP is a poorer Cre substrate than either single mutant loxP; thus, it is less likely to interfere with future genetic manipulations that use Cre. 3) The multiple cloning site contains Sfiα and Sfiβ restriction sites (Fig. 1F). Sfiα (CCGG TTAGT CCGG) and Sfiβ (CCGG TGCGT CCGG) are derivatives of Sfi1 (CCGGNNNNNCCGG), a rare eight base pair restriction site with five variable internal nucleotides that allow sticky directional cloning. 4) The TA contains a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter (Adra et al., 1987) so that an endogenous promoter is not essential for expression. 5) The parental iCMKIP is modular to rapidly accommodate changes by using strategically located rare eight base pair restriction endonuclease sites. The PGK promoter may be removed with (Pme1). SDSA within the TA may be removed with Swa1. SDSA within the inducible expression cassette may be removed with Pac1. Finally, PGK and the SDSA splice donor may be removed with Fse1 to leave only the splice acceptor; thus, a promoter-splice donor trap. 6) There are also SV40 (40) and bovine growth hormone (bA) (Pfarr et al., 1986) polyadenylation sequences. In the final configuration, there are three polyadenylation sequences separating the TA from the inducible expression cassette to minimize transcription read through (Maxwell et al., 1989). Thus, the parental iCMKIP has special features that are highly adaptable to fit the investigators needs.

We used two types of transactivator: tTA and reverse tTA (rtTA). Both contain the Tn10 tetracycline repressor (tetR) fused to the herpes simplex virus VP16 transcriptional activating domain. Yet, there are four amino acid changes such that dox binds to tTA to turn off cDNA expression (tet-off system) or binds to rtTA to turn on cDNA expression (tet-on system) (Gossen et al., 1995). For tTA, the PGK promoter and the splice donor of SDSA were removed with Fse1 (Fig. 1G) to enable trapping of Top3β exon 1 (exon 1 is noncoding) after Cre mediated recombination. For rtTA, the PGK promoter was removed with Pme1 (Fig. 1H); thus, the entire SDSA sequences are present. Even though the splice donor sequences remain, we anticipated splicing would still proceed from Top3β exon 1 to SDSA exon 2.

After Cre-mediated recombination, expression of the TA and eGFP were detected by RT-PCR. To detect TA expression, we observed a Top3β exon 1 + SDSA exon 2 + tTA (or rtTA) fusion transcript (Fig. 1E, red primers, dotted red lines); thus, the presence of the splice donor sequences did not influence splicing for iCMKIP shown in figure 1H as anticipated. To detect eGFP expression, we observed a SDSA exon 1 + exon 2 + eGFP fusion transcript (Fig. 1E, blue primers, dotted blue lines). Both RT-PCR products were verified by sequence analysis and showed the correctly spliced products.

For tTA, Western blot was used to compare the eGFP expression levels of five HAT resistant clones (Fig. 2A). There were somewhat variable expression levels. In particular clone five expressed less eGFP than the other four clones. This observation indicates clonal differences within a population of ES cells and demonstrates the need to quantitate expression levels.

Fig. 2.

Inducible expression of eGFP using tTA. (a) eGFP expression for 5 different clones (no dox). (b) Add 2μg/ml dox to turn off eGFP expression. (c) Remove dox to turn on eGFP expression. Time in days.

Western blot was used to measure inducible expression of eGFP for clone #3. GFP levels were greatly reduced 1day after addition of 2μg/ml dox; however, 3-4days was required for eGFP to be undetectable (Fig. 2B). Then dox was removed from the media to turn on expression. It took 3-4days to restore eGFP levels (Fig. 2C). Thus, Dox controls eGFP expression for tTA.

For rtTA, Western blot was used to measure inducible expression of eGFP for one clone. eGFP levels were enduced 1day after addition of 2μg/ml dox; however, 3-4days was required for full expression (Fig. 3A). Then dox was removed from the media to turn off expression. It took 3-4days to remove eGFP levels (Fig. 3B). Thus, Dox controls eGFP expression for rtTA.

Fig. 3.

Inducible expression of eGFP using rtTA. (a) Add 2μg/ml dox to turn on eGFP expression. (b) Remove dox to turn off eGFP expression. Time in days.

We are able to compare tTA to rtTA. For both, the impact of adding dox to the media was obvious within 24hrs; however, the full impact took two-three days longer. For both tTA and rtTA, the impact of removing dox from the media takes about three to four days. Thus, dox addition results in a quicker response than dox removal, likely due to the extra time needed to completely remove dox from the cell. Even though the relative effectiveness of tTA and rtTA is about the same, we believe the latter has multiple advantages. 1) rtTA required only one day to initiate eGFP expression as compared to four days for tTA. 2) Cells with rtTA do not need to be maintained in dox to keep the expression cassette turned off; long-term exposure to dox may have undesirable consequences, especially in mice. 3) rtTA is a better mimic of a small molecule therapeutic since addition of dox turns on expression. For example the inducible cDNA may be a dominant negative designed to ablate the function of a potential drug target; this cDNA would provide the proof of concept necessary to justify a small molecule screen. Thus, dox would mimic this small molecule.

Here we show Cre-mediated knock-in of the TA and eGFP using mouse ES cells. ES cells offer an advantage to other cell types since they may be used to generate genetically altered mice. This is essential for investigating complicated biological events like cancer incidence and spectrum. However, for basic cellular processes like DNA replication and DNA repair much can be learned from studying ES cells since they are more easily manipulated than mice and cost much less than mice. Therefore, we have established our knockin system in DNA repair genes like Trex2 (Dumitrache et al., 2008). ES cells are especially amenable to study cellular processes like DNA repair as long as cellular assays are available.

Our one-step knockin system has advantages over other transgenesis methods. Unlike random integration, one-step knockin ensures only a single copy of the TA and inducible expression cassette is present in the cell and these cassettes are in a defined location; therefore, there are fewer problems with chromatin position effects, multiple transgene units and mutation at the integration site. Unlike targeted transgenesis, one-step knockin utilizes an endogenous promoter to express the TA. Thus, there are two levels of expression regulation: first, the endogenous promoter and second, addition or subtraction of dox. Unlike knockin by gene targeting, our one-step inducible system does not require the generation of a new targeting vector and the isolation of new targeted cells for each project. In addition, the one-step system is very efficient since the Cre-mediated event is selectable. Finally, compared to all other transgenesis methods, our one-step system integrates both the TA and the inducible cassette in one-step as opposed to two steps. Thus, this one-step system is rapid and efficient and will save time, money and labor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of SDSA sequences

The SDSA sequences were generated by annealing 6 oligonucleotides. The splice donor and splice acceptor are bold. There are two versions: one with and one without an Fse1 site. Shown is the version with the Fse1 site (GGCCGGCC). For the version without the Fse1 site, the underlined cytosine’s are deleted. GCGGCCGCTTCGGGTGGACCCGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGGTCAACTTCAAGGTGAGCGGCGGGCCGGGAGAGTTCTGGGTCGAGGGGCGAGATGGCGCCTTCTTCTCAGGGCAGAGGATCACGGTGTAGCGCAGGCGGCCGGCCTGCGGGCCTGGGCCGCACTGATCCCTTTTTTTTCCACAGCTCGCGGTTGAGGACAACTCTTCGCGGTCGTCGAGTTAATTAAGGCCGGCCTTAGTGGCCGCCGCCACC

Knockin of iCMKIP

We used the previously generated AB2.2 ES cells that contain the 5′ half of miniHPRT upstream of Top3β exon 1 (Kim et al., 2008). To knockin iCMKIP, a co-transfection was performed with iCMKIP and a Cre expression cassette using culture conditions as previously described (Kim et al., 2008). HAT resistant clones were picked and verified for Cre-mediated knockin using PCR as described. The restored miniHPRT may then be removed along with the plasmid backbone using FLP recombination (Schaft et al., 2001), but this step is optional and not done here.

RT-PCR to detect the Top3β exon1 + SDSA exon 2 + tTA (rtTA) fusion transcript

We used the trizol method for RNA isolation.

PCR conditions; 35 cycles of 98°C for 30sec, 64°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 45 sec.

Primers; Top3 β forward primer (E1F; 5′ CGGAATGGTAGCAGCGCTCC 3′) and TA reverse primer (TA; 5′ CCATGGTAGACCCGTAATTG 3′). This amplifies a 915bp band.

RT-PCR to detect the SDSA exon 1+ SDSA exon 2 + eGFP fusion transcript

PCR conditions; 35 cycles of 98°C for 30sec, 64°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 45 sec.

Primers; Globin RT PCR For2 primer (5′ CCAGTGGTCAACTTCAAG 3′) and eGFP reverse primer (GFP; 5′GCTCAGGGCGGACTGGGTGCTC 3′). This amplifies a 744bp band.

Western blot

Standard conditions were used for Western. To prepare cell lysate, ES cells were grown to confluence on 6 well plates. Cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, collected, spun down, lysed in 150mM NaCl, 10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 1% Sodium deoxycholate containing protease inhibitor. Extracts were clarified by centrifugation for 10min and were immunoblotted with GFP Monoclonal antibody (JL-8; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and with α-β-actin antibody (A2105; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to manufacturer instructions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Charnae Williams for technical expertise and Dr. Allan Bradley for the gift of AB2.2 ES cells. This work was supported by the following NIH grants to PH: 1 RO1 CA123203-01A1 and P01 AG17242.

References

- Adra CN, Boer PH, McBurney MW. Cloning and expression of the mouse pgk-1 gene and the nucleotide sequence of its promoter. Gene. 1987;60:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Shawi R, Kinnaird J, Burke J, Bishop JO. Expression of a foreign gene in a line of transgenic mice is modulated by a chromosomal position effect. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1192–1198. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K, Araki M, Yamamura K. Targeted integration of DNA using mutant lox sites in embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:868–872. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias L, Nishida Y, Mintz B. Early postimplantation embryo lethality due to DNA rearrangements in a transgenic mouse strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:6020–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrache LC, Hu L, Hasty P. TREX2 exonuclease defective cells exhibit double-strand breaks and chromosomal fragments but not Robertsonian translocations. Mutat Res. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Muller G, Hillen W, Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks M, Wurst W, Anson-Cartwright L, Auerbach AB, Joyner AL. Rescue of the En-1 mutant phenotype by replacement of En-1 with En-2. Science. 1995;269:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.7624797. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillen W, Berens C. Mechanisms underlying expression of Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:345–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb VB, Kim TM, Dumitrache LC, Ma SM, Chen MJ, Hasty P. HPRT minigene generates chimeric transcripts as a by-product of gene targeting. Genesis. 2007;45:275–281. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasin M, Moynahan ME, Richardson C. Targeted transgenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8804–8808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T-M, Choi YJ, H KJ, Hasty P. High througput knock-in coupling gene targeting with the HPRT minigene and Cre-mediated recombination. Genesis. 2008 doi: 10.1002/dvg.20439. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell IH, Harrison GS, Wood WM, Maxwell F. A DNA cassette containing a trimerized SV40 polyadenylation signal which efficiently blocks spurious plasmid-initiated transcription. Biotechniques. 1989;7:276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough AJ, Berget SM. G triplets located throughout a class of small vertebrate introns enforce intron borders and regulate splice site selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4562–4571. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfarr DS, Rieser LA, Woychik RP, Rottman FM, Rosenberg M, Reff ME. Differential effects of polyadenylation regions on gene expression in mammalian cells. DNA. 1986;5:115–122. doi: 10.1089/dna.1986.5.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren EP, Palmiter RD, Heckel JL, Daugherty CC, Brinster RL, Degen JL. Complete hepatic regeneration after somatic deletion of an albumin- plasminogen activator transgene. Cell. 1991;66:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaft J, Ashery-Padan R, van der Hoeven F, Gruss P, Stewart AF. Efficient FLP recombination in mouse ES cells and oocytes. Genesis. 2001;31:6–10. doi: 10.1002/gene.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin MK, Levorse JM, Ingram RS, Tilghman SM. The temporal requirement for endothelin receptor-B signalling during neural crest development. Nature. 1999;402:496–501. doi: 10.1038/990040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian JL, Klein WH, Hasty P. Temporal, spatial and tissue-specific expression of a myogenin-lacZ transgene targeted to the Hprt locus in mice. Biotechniques. 1999;27:154–162. doi: 10.2144/99271rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]