Abstract

The emergence of glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium (GREF) in a Greek intensive care unit was studied by amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis and esp gene detection. Three GREF clones harboring the esp gene were recovered from 17 out of 21 patients, indicating the dissemination of genetically homogenous and virulent strains of GREF.

Glycopeptide-resistant enterococci (GRE) have become increasingly important as a cause of hospital-acquired infections. By the year 2000, 25.9% of enterococci isolated from intensive care units (ICUs) in the United States were vancomycin resistant (3). Although first detected in France and England, GRE strains have not disseminated extensively in Europe, having an incidence of less than 3% (2, 13). However, the number of GRE-affected European hospitals is now increasing (2).

Previously considered low-virulence pathogens, enterococci can cause life-threatening infections. Traits that have been mentioned as potential virulence factors include antibiotic resistance determinants, a cytolytic toxin, gelatinase, an aggregation substance, extracellular superoxide production, and the enterococcal surface protein (Esp) (7, 14, 15). The enterococcal surface protein gene (esp), encoding a cell wall-associated peptide, was originally found in Enterococcus faecalis (14). Recently a variant esp gene has been detected in glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium (GREF) strains from hospital outbreaks, while it was absent in all nonepidemic and animal isolates, suggesting that its presence is a marker of increased virulence (18).

In Greece, following the detection of an increasing proportion of E. faecium strains in ICU patients (12), GREF infections first emerged in February 1999 (11). During the next 30 months, we experienced a GREF outbreak with 21 ICU patients infected. To control the spread of glycopeptide-resistant strains, we studied the characteristics of this outbreak, focusing on molecular typing with amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis and esp gene detection. AFLP analysis was used to investigate the genetic relationship among the GREF strains, as this technique is fast, reproducible, and as discriminatory as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for studying the molecular epidemiology of enterococci (1, 16, 17).

Identification and antibiotic susceptibility.

Identification of enterococci was performed by classic methods and PASCO identification panels. MICs of ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin (500 μg/ml), streptomycin (1,000 μg/ml), tetracycline, rifampin, teicoplanin, and vancomycin were determined by the broth microdilution method (PASCO system). The susceptibility testing was performed according to NCCLS guidelines (9). E. faecalis ATCC 29212 was used as quality control strain. The MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin were also determined by E test.

Molecular typing.

The presence of the vanA gene and esp gene was detected by PCR as proposed by Dutka-Malen et al. (6) and Shankar et al. (14), respectively. The expected esp PCR product size was 510 bp. AFLP analysis was performed as described by Willems et al. (17).

From February 1999 to April 2001, GREF strains were isolated from 21 medical and surgical patients in the multidisciplinary ICU (Table 1). Characteristics of the patients and the GREF strains are shown in Table 1. The esp gene was present in 17 of the 21 strains. None of the esp-negative strains came from blood. GREF strains from patients 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11 were isolated in the same month and in the same ward of the ICU.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of ICU patients and the isolated vanA GREF strains

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | LOSa (days)

|

ICU outcomeb | Source | Date of isolation (day/mo/yr) | MIC (μg/ml) ofc:

|

Presence of esp gene | AFLP pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Preinfection | VA | TC | |||||||

| 1 | 65 | 60 | 57 | D | Blood | 26/2/99 | 256 | 128 | + | C1 |

| 2 | 40 | 12 | 10 | D | Drainage | 2/3/99 | >256 | 128 | + | C1 |

| 3 | 75 | 79 | 51 | D | Blood | 23/3/99 | 256 | 128 | + | C1 |

| 4 | 64 | 66 | 32 | A | Blood | 1/8/99 | >256 | 64 | + | C1 |

| 5 | 27 | 56 | 50 | A | Drainage | 11/9/99 | >256 | 128 | + | C1 |

| 6 | 69 | 98 | 66 | A | Catheter | 5/7/00 | 256 | 64 | + | C2 |

| 7 | 64 | 48 | 41 | D | Peritoneal fluid | 13/6/00 | 256 | 128 | + | C3 |

| 8 | 50 | 43 | 15 | A | Drainage | 1/7/00 | 256 | 128 | + | C2 |

| 9 | 50 | 70 | 22 | A | Blood | 4/7/00 | >256 | 128 | + | C3 |

| 10 | 25 | 140 | 30 | A | Blood | 4/7/00 | >256 | 128 | + | C2 |

| 11 | 62 | 41 | 30 | A | Catheter | 7/7/00 | >256 | 128 | + | C2 |

| 12 | 44 | 320 | 150 | D | Urine | 6/9/00 | >256 | 64 | + | C2 |

| 13 | 40 | 58 | 23 | A | Blood | 3/10/00 | >256 | 128 | + | C2 |

| 14 | 83 | 36 | 24 | D | Blood | 28/10/00 | >256 | 64 | + | C2 |

| 15 | 16 | 75 | 30 | A | Fluid of wound | 6/11/00 | >256 | 64 | + | C2 |

| 16 | 36 | 53 | 35 | A | Drainage | 20/11/00 | >256 | 16 | + | C2 |

| 17 | 40 | 98 | 53 | D | Peritoneal fluid | 6/2/01 | >256 | 128 | − | C5 |

| 18 | 27 | 36 | 25 | A | Drainage | 5/3/01 | >256 | 128 | − | C5 |

| 19 | 63 | 23 | 18 | D | Fluid of wound | 7/3/01 | >256 | 128 | − | C5 |

| 20 | 60 | 25 | 9 | D | Drainage | 31/3/01 | >256 | 128 | − | C4 |

| 21 | 63 | 23 | 17 | D | Fluid of wound | 2/4/01 | >256 | 128 | + | C6 |

LOS, length of stay.

D, dead; A, alive.

VA, vancomycin; TC, teicoplanin.

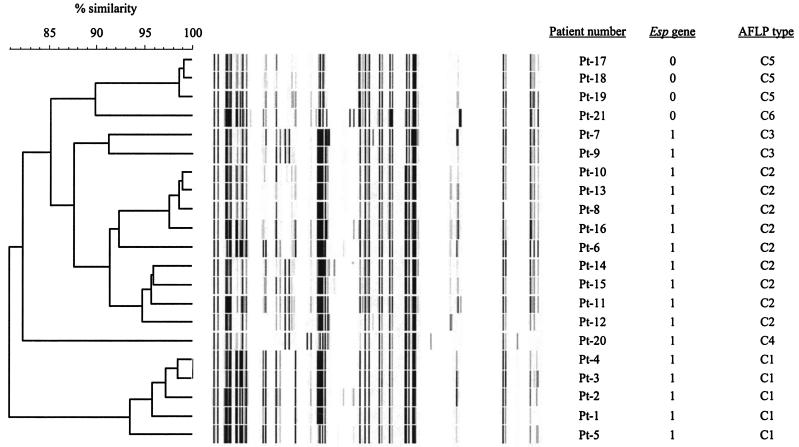

The genetic relationships, as determined by the AFLP banding patterns, are shown in Fig. 1. All strains formed a highly homologous group since AFLP banding patterns were at least for 80% similar. GREF isolates with a similarity of >90% between AFLP patterns were considered identical (18). Based on these criteria six different AFLP types (clones C1 to C6) were discerned. AFLP types are shown in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram of the genetic similarity of all isolates by AFLP analysis. AFLP types are based on 90% genetic similarity. The presence (1) or absence (0) of the esp gene is indicated.

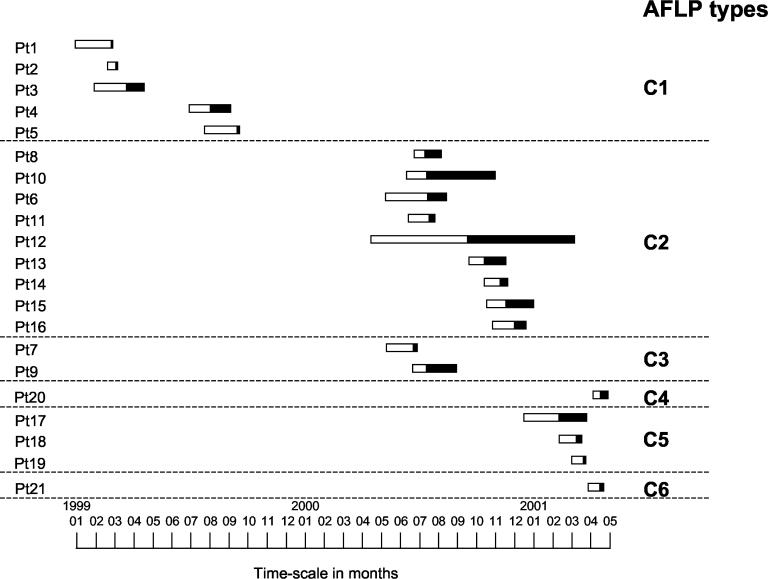

Figure 2 describes the relationship between the length of ICU stay for each patient, the preinfection period, the infection period, and AFLP types during the study period. Isolates belonging to clones C2 and C3 were recovered during the same period of time. This and the fact that clones C2 and C3 are highly similar suggest that these isolates belong in fact to a single clone (C2/3). The same is probably true for the esp-negative isolates belonging to clones C5 and C6. In summary, these results show that, during the period February 1999 to April 2001, three different GREF clones (C1, C2/3, and C4) harboring the esp virulence gene were recovered from clinical sites, mainly blood, of 17 patients. In addition, one GREF clone (C5/6) lacking the esp gene was isolated from peritoneal fluid, drainage, and wound fluid of four patients.

FIG. 2.

Admission of patients at the ICU. Bars indicate the preinfection period (open part) and infected period (solid part). The numbers on the left are the patient numbers.

The predominance of the species E. faecium among GRE has been widely reported. vanA E. faecium was mainly responsible for the emergence and the dissemination of glycopeptide resistance in European hospitals (2), while in the United States, the GRE isolates show considerable diversity, with vanB resistance also being a common type (4, 8).

All GREF strains isolated during July 2000, when the peak of the outbreak occurred, were esp positive, which may indicate an increased virulence associated with the presence of esp. Our findings seemingly contrast with the results of Shankar et al. (14), who found the esp gene in 43 out of 133 infection-derived E. faecalis isolates and did not find it in 34 E. faecium isolates, but they are in accordance with those of Willems et al. (18), who detected the gene in vancomycin-resistant E. faecium strains associated with hospital outbreaks.

The esp gene has also been detected in glycopeptide-susceptible E. faecium strains (5; L. Baldassari, L. Bertuccini, M. G. Ammendolia, G. Gherardi, and R. Creti, Letter, Lancet 357:1802, 2001; N. Woodford, M. Soltani, and K. J. Hardy, Letter, Lancet 358:584, 2001), supporting the hypothesis that esp-positive E. faecium strains may have existed for some time, even before the acquisition of resistance to glycopeptides. We did not screen for esp gene-positive glycopeptide-susceptible E. faecium (GSEF) strains since it was not the rationale of this study. Therefore, we have no data on the frequency of esp-positive GSEF strains in our ICU.

In general, GRE isolates are genetically diverse (4), while single clones have also been reported in outbreaks on single hospital wards (10). However, the molecular epidemiology of GRE within an institution may change over time, going from an epidemic situation to the establishment of endemicity (8). In the present study, the transmission of a particular clone could be explained by the fact that infected patients stayed in the ICU during overlapping periods of time. Interestingly, the disappearance of one particular GREF clone was followed by the appearance of another. In addition the acquisition of GREF occurred 30 days (median value) after the ICU admission. These findings strongly suggest intra-ICU transmission of GREF strains.

In summary, genetically homogenous GREF strains harboring the esp virulence gene were identified during the emergence and the evolving outbreak of GREF infections in our ICU. The results of this study emphasize the importance of molecular monitoring of GREF infections in understanding their epidemiology and may be useful to control and prevent their further spread.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonishyn, N. A., R. R. McDonald, E. L. Chan, G. Horsman, C. E. Woodmansee, P. S. Falk, and C. G. Mayhall. 2000. Evaluation of fluorescence-based amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis for molecular typing in hospital epidemiology: comparison with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for typing strains of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4058-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonten, M. J. M., R. Willems, and R. A. Weinstein. 2001. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: why they are here, and where do they come from? Lancet Infect. Dis. 1:314-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Preventation. National nosocomial infections surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from January 1990-May 1999, issued June 1999. Am. J. Infect. Control 27:520-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark, N. C., R. C. Cooksey, B. C. Hill, J. M. Swenson, and F. C. Tenover. 1993. Characterization of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 37:2311-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coque, T. M., R. Willems, R. Canton, R. Del Campo, and F. Baquero. 2002. High occurrence of esp among ampicillin-resistant and vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium clones from hospitalized patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:1035-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutka-Malen, S., S. Evers, and P. Courvalin. 1995. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:24-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jett, B. D., M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmon. 1994. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim, W. J., R. A. Weinstein, and M. Hayden. 1999. The changing molecular epidemiology and establishment of endemicity of vancomycin resistance in enterococci at one hospital over a 6-year period. J. Infect. Dis. 179:163-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 10.Pegues, D. A., C. F. Pegues, P. L. Hibbert, D. S. Ford, and D. C. Hooper. 1997. Emergence and dissemination of a highly vancomycin-resistant vanA strain of Enterococcus faecium at a large teaching hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1565-1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platsouka, E. D., H. Dimopoulou, V. Miriagou, and O. Paniara. 2000. The first clinical isolates of Enterococcus faecium with the VanA phenotype in a tertiary Greek hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:1039-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Routsi, C., E. Platsouka, O. Paniara, E. Dimitriadou, G. Saroglou, C. Roussos, and A. Armaganidis. 2000. Enterococcal infections in a Greek intensive care unit: a 5-year study. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 32:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schouten, M. A., A. Voss, and J. A. Hoogkamp-Korstanje. 1999. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of enterococci causing infections in Europe. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2542-2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankar, V., A. S. Baghdayan, M. M. Huycke, G. Lindah, and M. S. Gilmore. 1999. Infection-derived Enterococcus faecalis strains are enriched in esp, a gene encoding a novel surface protein. Infect. Immun. 67:193-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergis, E. N., N. Shankar, J. W. Chow, M. K. Hayden, D. R. Snydman, M. J. Zervos, P. K. Linden, M. M. Wagener, and R. R. Muder. 2002. Association between the presence of enterococcal virulence factors gelatinase, hemolysin, and enterococcal surface protein and mortality among patients with bacteremia due to Enterococcus faecalis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:570-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. van de Lee, M. Hornes, A. Frijters, J. Pot, J. Peleman, M. Kuiper, et al. 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4407-4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willems, R. J. L., J. Top, N. van den Braak, A. van Belkum, H. Endtz, D. Mevious, E. Stobberingh, A. van den Bogaard, and J. D. A. van Embden. 2000. Host specificity of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. J. Infect. Dis. 182:816-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willems, R. J. L., W. Homan, J. Top, M. van Santen-Verheuvel, D. Tribe, X. Manzioros, C. Gaillard, C. M. Vandenbroucke, E. M. Mascini, E. van Kregten, J. D. van Embden, and M. J. Bonten. 2001. Variant esp gene as a marker of a distinct genetic lineage of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium spreading in hospitals. Lancet 357:853-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]