Abstract

Mitochondrial cytochrome b genes (cyt b) of 40 strains of Cryptococcus neoformans were partially sequenced to determine the genetic relations. With the exception of the type strain of C. neoformans var. neoformans, all strains contained introns in their sequences. Analysis of 386 bp of coding sequence from each strain under investigation revealed a total of 27 (6.99%) variable nucleotide sites and categorized isolates of C. neoformans into nine cyt b types. C. neoformans var. gattii included cyt b types I to V, and C. neoformans var. neoformans comprised types VI to IX. cyt b types were correlated with serotypes. All strains with cyt b types I, IV, and V were serotype B. All other strains except IFM 5878 (serotype B) with cyt b types II and III were serotype C. Serotype D strains had cyt b types VI and IX, and serotype A strains were cyt b type VIII. Of four serotype AD strains, one was cyt b type VII and the remaining three were type VIII. The phylogenetic tree based on deduced amino acid sequences divided the strains only into C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. neoformans var. gattii. These results indicate that cyt b sequences are effective for DNA typing as well as phylogenetic analysis of C. neoformans.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated basidiomycetous yeast and is the causative agent of cryptococcosis. The incidence of cryptococcosis, which was formerly a relatively rare disease, has increased markedly in recent years because of the increases in the numbers of AIDS patients and organ transplantation patients. Meningitis and, to a lesser extent, pneumonia are the most frequent life-threatening manifestations of cryptococcosis (6, 15, 18, 21).

Isolates of C. neoformans from patients with cryptococcosis have been divided into five serotypes, A, B, C, D, and AD, on the basis of the immunologic properties of the capsular polysaccharides (9, 15, 16, 20). These five serotypes have been grouped into two separate varieties: C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotypes A, D, and AD) and C. neoformans var. gattii (serotypes B and C) (11-13, 23).

The issue of C. neoformans nomenclature is still unsettled. Franzot et al. (7) proposed that C. neoformans var. neoformans strains be subdivided into two varieties, C. neoformans var. neoformans (serotype D) and C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A), on the basis of sequence fingerprint data for the C. neoformans repetitive element 1 and nucleotide sequence analyses of the URA5 gene. Sequence analysis of the CAP59 gene (19) revealed a phylogenetic separation between serotypes A and D. The two serotypes can also be differentiated by analysis of mating type (MAT) genes, MATα and MATa (3). However, analysis of the D1/D2 region of the large-subunit ribosomal DNA (rDNA), which is widely used for phylogenetic analysis, revealed that the sequences of serotype A (CBS 132; DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF075484) and serotype D (CBS 882; DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AF189845) strains were identical. There is only one nucleotide difference between the D1/D2 sequences of Fidobasidiella neoformans var. neoformans and F. neoformans var. bacillispora (5). Analysis of the sequence of the intergenic spacer associated with rDNA suggested that C. neoformans var. grubii (serotype A) should not be considered a separate variety and instead that Cryptococcus isolates should be considered two separate species, C. neoformans (serotypes A, D, and AD) and Cryptococcus bacillisporus (serotypes B and C, synonymous with C. neoformans var. gattii) (4).

Mitochondrial (mt) genes are an attractive marker for inferring phylogeny of closely related species because of the rapid evolution of the mt genome, the lack of recombination, and the strict maternal inheritance (17). Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of mtDNA has been shown to be useful for estimating the relations between fungi (8, 10, 24). Xu et al. (29) showed that the origin of mitochondria in C. neoformans is uniparental. RFLP analysis of the mt large rRNA gene and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 gene allowed efficient screening of the mtDNA of C. neoformans (28).

We have reported that the mt cytochrome b gene (cyt b) is useful for identification, classification, and phylogenetic analysis of fungi (25-27, 31). We have also shown that mt cyt b sequences are effective for identifying and studying the phylogenetic relations of closely related yeasts such as Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis (30). cyt b is useful for typing isolates of Candida albicans and differentiating such isolates from Candida stellatoidea (1). We have also shown that the cyt b phylogeny of basidiomycetous yeasts correlates with cell wall biochemistry and septal ultrastructure (2). However, similar techniques have not been used to characterize C. neoformans.

In the present study, mt cyt b genes of 40 strains of C. neoformans (15 strains of C. neoformans var. gattii and 25 strains of C. neoformans var. neoformans) were analyzed to determine the genetic relations. Isolates of C. neoformans were divided into nine cyt b types; however, the deduced amino acid sequences suggested the existence of only two varieties: C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. neoformans var. gattii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. neoformans strains and serotyping.

The C. neoformans strains, both environmental and clinical isolates, and the reference cultures used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were grown on YPD (1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] polypeptone, 2% [wt/vol] glucose) slants. The serotypes of the clinical and environmental strains were determined by slide agglutination tests (Crypto Check; Iatron Laboratories, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

TABLE 1.

C. neoformans strains used in this study

| Variety | IFM no. | Serotype | DNA type | AAa type | Exon position(s) (nt) | Source | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5815 | B | I | I | 1-46, 461-800 | Patient | AB105913 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48634 | B | I | I | 1-46, 461-800 | CBS 6289 | AB105914 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48636 | B | I | I | 1-46, 454-793 | CBS 7229 | AB105915 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48819 | B | I | I | 1-46, 461-800 | CBS 6998 | AB105916 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48820 | B | I | I | 1-46, 461-800 | CBS 8273 | AB105917 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48821 | B | I | I | 1-46, 454-793 | CBS 7749 | AB105918 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5856 | C | II | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1148-1171 | NIH 18 | AB105919 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5873 | C | II | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1148-1171 | Patient | AB105920 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5875 | C | II | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1148-1171 | Patient | AB105921 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5878 | B | II | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1121-1144 | Patient | AB105922 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48635 | C | III | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1162-1185 | CBS 6955T | AB105923 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 5855 | B | IV | I | 1-46, 317-632, 1162-1185 | NIH 112 | AB105924 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 47258 | B | V | I | 1-46, 1175-1514 | Patient | AB105925 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48818 | B | V | I | 1-46, 1175-1514 | CBS 6956 | AB105926 |

| C. neoformans var. gattii | 48822 | B | V | I | 1-46, 1175-1514 | CBS 7750 | AB105927 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5844 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105928 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5845 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105929 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5857 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | NIH 52 | AB105930 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5881 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105931 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46082 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105932 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46090 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105933 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48640 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | CBS 6901 | AB105934 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48641 | Db | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | CBS 6995 | AB105935 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48642 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | CBS 7697 | AB105936 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48643 | D | VI | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | CBS 7698 | AB105937 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5889 | AD | VII | II | 1-46, 1190-1529 | Patient | AB105938 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5505 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Patient | AB105939 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5506 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Patient | AB105940 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 5854 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | CDC 551 | AB105941 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 45708 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Patient | AB105942 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 45737 | AD | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Pigeon droppings | AB105943 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 45756 | AD | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Pigeon droppings | AB105944 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46132 | AD | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Pigeon droppings | AB105945 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46554 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Patient | AB105946 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46572 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Patient | AB105947 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46729 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Pigeon droppings | AB105948 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 46734 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | Pigeon droppings | AB105949 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48638 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | CBS 996 | AB105950 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48639 | A | VIII | II | 1-46, 1189-1528 | CBS 5756 | AB105951 |

| C. neoformans var. neoformans | 48637 | D | IX | II | 1-386 | CBS 132T | AB040655c |

AA, amino acid.

IFM 48641 is regarded as a serotype A strain in the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Baarn, The Netherlands), but repeated checking in our laboratory showed serotype D.

Biswas et al. (2).

Isolation of DNA.

One loopful of cells from each YPD slant was suspended in 1 ml of sterile distilled water and used for extraction of total cellular DNA with the Gen Toru Kun kit (Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Otsu, Shiga, Japan) as described previously (30).

PCR primers and amplification of the cyt b gene.

PCR primers E1M4 (5′-TGRGGWGCWACWGTTATTACTA-3′) and E2M4 (5′-GGWATAGMWSKTAAWAYAGCATA-3′) (R, A or G; W, A or T; M, A or C; S, C or G; K, G or T; Y, C or T) were designed as described previously (25). One microliter of extracted DNA was used as the template for amplification of the mt cyt b with a TaKaRa Ex Taq PCR amplification kit (Takara Shuzo). Reactions were performed in a final reaction volume of 50 μl containing 10 pmol of each primer, 4 μl of 2.5 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 2.0 U of TaKaRa Ex Taq polymerase, and 5 μl of 10× reaction buffer (Takara Shuzo). Amplification conditions were 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 50°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Sequencing.

PCR products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Both strands of PCR products were sequenced directly with an ABI Prism 377 or 310 DNA sequencer with a Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Amino acid sequences were deduced from the DNA sequences with the yeast mt genetic code.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis.

With the exclusion of the portions of the sequences that included the primers, DNA and amino acid sequences were aligned with GENETYX-MAC genetic information processing software (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). This software also generated phylogenetic trees by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences of the cyt b genes of the C. neoformans strains sequenced in this study have been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

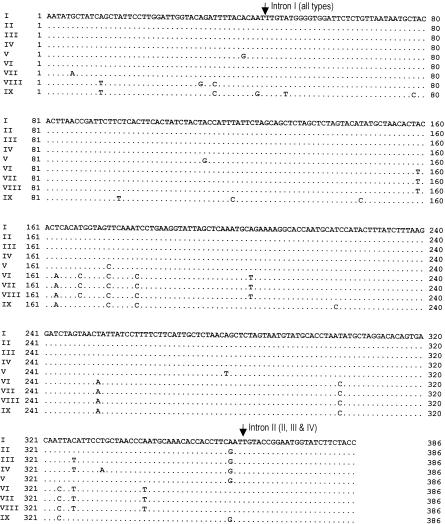

The 386-bp fragment corresponding to nucleotides (nt) 445 to 830 of the Candida glabrata cyt b coding sequence (GenBank accession no. X53862) was analyzed in this study. The type strain of C. neoformans var. neoformans, IFM 48637, had no introns in this region of cyt b. However, all other strains investigated contained one intron that started after nt 46 of the sequence (Fig. 1); the size of this intron varied from 270 to 1,143 bp. Some isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii contained a second intron that began at nt 633 of the cyt b sequence (Table 1) or nt 363 of the coding sequence (Fig. 1). The size of the second intron varied from 515 to 529 bp. The sizes and locations of these introns were determined as described previously (2) through comparison of strains with and without introns to maximize amino acid identities. Isolates of C. neoformans var. neoformans contained the longest introns, which were 1,142 and 1,143 bp. Among isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii, IFM 47258, IFM 48818, and IFM 48822 contained introns similar in size (1,128 bp) to that of C. neoformans var. neoformans and with greater than 96% sequence identity. Although the intron sizes were variable, they were fixed for specific cyt b types (Table 1), with the exception of strains IFM 48636 and 48821 (cyt b type I) and IFM 5878 (cyt b type II).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of coding sequences of the mt cyt b genes of various C. neoformans isolates. Dots, nucleotides that are identical to those of C. neoformans cyt b type I; arrows, positions of introns. Cyt b types are in parentheses.

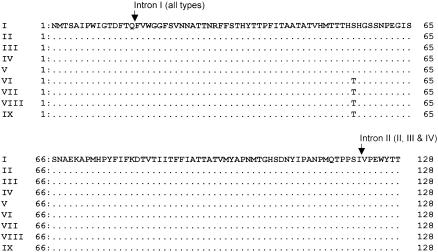

Analysis of 386 bp of coding sequence of cyt b revealed 27 (6.99%) variable nucleotide sites (Fig. 1). To ensure that these variations were not due to polymerase errors, we used the TaKaRa Ex Taq polymerase, which has an approximately fourfold-lower error rate than standard Taq DNA polymerase. Moreover, we sequenced both strands of each PCR product and repeated each PCR and sequencing reaction. On the basis of these differences in cyt b, the C. neoformans strains we analyzed were divided into nine types: C. neoformans var. gattii comprising cyt b types I to V and C. neoformans var. neoformans comprising cyt b types VI to IX (Table 1 and Fig. 1). All strains with cyt b types I, IV, and V were serotype B; all strains with cyt b types II and III except IFM 5878 (serotype B) were serotype C. Serotype D strains had cyt b types VI and IX, and serotype A strains were cyt b type VIII. Of four serotype AD strains, one was cyt b type VII and the remaining three were cyt b type VIII. Although the cyt b sequences contained 27 variable nucleotides (Fig. 1), the deduced amino acid sequences revealed that only one of these substitutions was nonsynonymous. C. neoformans var. gattii isolates, with cyt b types I to V, had identical amino acid sequences (type AA-I). Similarly, isolates of C. neoformans var. neoformans, with cyt b types VI to IX, had identical amino acid sequences (type AA-II). Therefore, isolates of C. neoformans var. neoformans differed from those of C. neoformans var. gattii only at amino acid position 55 (Thr instead of Ser) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by the cyt b genes of various C. neoformans isolates. Dots, amino acids that are identical to those of C. neoformans cyt b type I; arrows, inserted positions of introns. cyt b types are in parentheses.

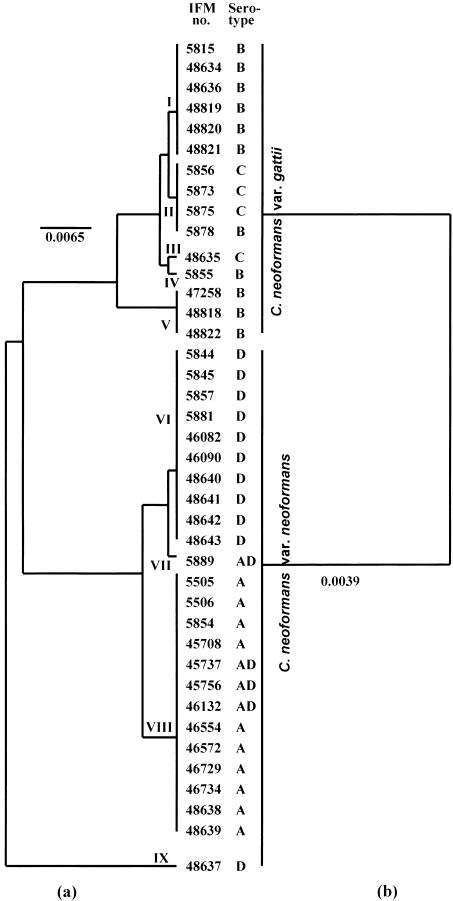

The phylogenetic trees (UPGMA) generated from the mt cyt b DNA and amino acid sequences are shown in Fig. 3. The strains of C. neoformans were distributed according to nine DNA types. The type strain of C. neoformans var. neoformans (IFM 48637) was the outgroup in the phylogenetic tree. IFM 48637 contained the most variable nucleotide sites in cyt b (Fig. 1) and showed only a distant relation with other strains, even those of C. neoformans var. neoformans. Strains with cyt b type V (C. neoformans var. gattii IFM 47258, IFM 48818, and IFM 48822) contained introns similar in both length and content to that of C. neoformans var. neoformans, and they were phylogenetically closer to C. neoformans var. neoformans. Analysis of mt cyt b sequences suggested the existence of nine DNA types of C. neoformans; however, the phylogenetic tree based on the deduced amino acid sequences divided the strains into only two varieties: C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. neoformans var. gattii.

FIG. 3.

UPGMA-based trees showing the relations of various C. neoformans isolates generated from nucleotide sequences of the cyt b gene (exon) (a) and deduced amino acid sequences (b). Bar, number of nucleotide and amino acid substitutions per nucleotide site and amino acid site.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first study where mt cyt b sequences were used to analyze the genetic relations of strains of C. neoformans. Isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii, the anamorphic state of F. neoformans var. bacillispora, had five types (I to V) for mt cyt b; however, the deduced amino acid sequences were identical. Similarly, the amino acid sequences encoded by mt cyt b genes of isolates of C. neoformans var. neoformans, which is the anamorphic state of F. neoformans var. neoformans, were identical although there were four cyt b types (VI to IX). This result is consistent with the varieties of C. neoformans var. neoformans and var. gattii distinguished by d-proline assimilation or reaction on l-canavanine-glycine-bromthymol blue agar (11, 14).

The present study also revealed that one serotype D strain (cyt b type IX) had no intron in the region sequenced; however, all other strains of C. neoformans contained one intron, and some isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii contained a second intron (Table 1 and Fig. 2). A recent study of the mt COX1 gene of C. neoformans indicated that the presence or absence of introns in COX1 is not serotype specific (22), which is similar to the outcome of our study. The same group also reported that serotype D strains contain more introns in COX1 than do serotype A strains. However, in our study of the cyt b gene, all serotype A and D strains except IFM 48637 contained a single intron and the introns from all strains were similar in size and nucleotide sequence. The first intron in cyt b of C. neoformans started at nt 47 (Fig. 2), which is the same position as intron 2 of Neurospora crassa cyt b gene. Rhodotorula acheniorum and Rhodotorula ferulica, two other basidiomycetous yeasts, have introns in the same location (2). Some isolates of C. neoformans var. gattii (cyt b types II, III, and IV) contained a second intron that began at nt 633 (Table 1), which is similar to the location of intron 5 of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyt b gene. These findings suggest two possible evolutionary events. The first possibility is that these introns appeared in these locations prior to the separation of these species and that some species lost introns over time. The second is that these introns appeared in these locations after separation of these species.

Analysis of the mt large rRNA gene and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 of C. neoformans revealed that serotype AD strains had either the serotype A or serotype D mtDNA genotype (29). In the present study, we obtained almost similar results for the distribution of cyt b gene types in serotype AD strains. Of four serotype AD strains, three had serotype A-specific cyt b (type VIII) and one had a unique specific cyt b (type VII) that was nearly identical to serotype D-specific cyt b (type VI), with only 1 nt difference.

In conclusion, we have shown that isolates of C. neoformans represent nine cyt b types; however, the deduced amino acid sequences indicate that there are only two varieties, C. neoformans var. neoformans and C. neoformans var. gattii.

Acknowledgments

This study was performed as part of the program Frontier Studies and International Networking of Genetic Resources in Pathogenic Fungi and Actinomycetes (FN-GRPF) through the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (2001).

REFERENCES

- 1.Biswas, S. K., K. Yokoyama, L. Wang, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 2001. Typing of Candida albicans isolates by sequence analysis of the cytochrome b gene and differentiation from Candida stellatoidea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1600-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas, S. K., K. Yokoyama, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 2001. Molecular phylogenetics of the genus Rhodotorula and related basidiomycetous yeasts inferred from the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1191-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaturvedi, S., B. Rodeghier, J. Fan, C. M. McClelland, B. L. Wickes, and V. Chaturvedi. 2000. Direct PCR of Cryptococcus neoformans MATα and MATa pheromones to determine mating type, ploidy, and variety: a tool for epidemiological and molecular pathogenesis studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2007-2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz, M. R., T. Boekhout, B. Theelen, and J. W. Fell. 2000. Molecular sequence analyses of the intergenic spacer (IGS) associated with rDNA of the two varieties of the pathogenic yeast, Cryptococcus neoformans. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:535-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fell, J. W., T. Boekhout, A. Fonseca, G. Scorzetti, and A. Statzell-Tallman. 2000. Biodiversity and systematics of basidiomycetous yeasts as determined by large-subunit rDNA D1/D2 domain sequence analysis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1351-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franzot, S. P., J. S. Hamdan, B. P. Currie, and A. Casadevall. 1997. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptococcus neoformans in Brazil and the United States: evidence for both local genetic differences and a global clonal population structure. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2243-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzot, S. P., I. F. Salkin, and A. Casadevall. 1999. Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii: separate varietal status for Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:838-840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamari, Z., F. Kevei, E. Kovacs, J. Varga, Z. Kozakiewicz, and J. H. Croft. 1997. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Aspergillus japonicus and Aspergillus aculeatus strains with special regard to their mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 72:337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikeda, R., T. Shinoda, Y. Fukazawa, and L. Kaufman. 1982. Antigenic characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans serotypes and its application to serotyping of clinical isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16:22-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozlowski, M., and P. P. Stepien. 1982. Restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA of members of the genus Aspergillus as an aid in taxonomy. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:471-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon-Chung, K. J., I. Polacheck, and J. E. Bennett. 1982. Improved diagnostic medium for separation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotypes A and D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii (serotypes B and C). J. Clin. Microbiol. 15:535-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1984. Epidemiologic differences between the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Am. J. Epidemiol. 120:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon-Chung, K. J., B. L. Wickes, L. Stockman, G. D. Roberts, D. Ellis, and D. H. Howard. 1992. Virulence, serotype, and molecular characteristics of environmental strains of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. Infect. Immun. 60:1869-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon-Chung, K. J. 1998. Filobasidiella Kwon-Chung, p. 656-662, In C. P. Kurtzman and J. W. Fell (ed.), The yeasts, a taxonomic study, 4th ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 15.Levitz, S. M. 1991. The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of cryptococcosis. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:1163-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, A., K. Nishimura, H. Taguchi, R. Tanaka, S. Wu, and M. Miyaji. 1993. The isolation of Cryptococcus neoformans from pigeon droppings and serotyping of naturally and clinically sourced isolates in China. Mycopathologia 124:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manceau, V., L. Despres, J. Bouvet, and P. Taberlet. 1999. Systematics of the genus Capra inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 13:504-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell, T. G., and J. R. Perfect. 1995. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS—100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:515-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura, Y., R. Kano, S. Watanabe, and A. Hasegawa. 2000. Molecular analysis of CAP59 gene sequences from five serotypes of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:992-995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishikawa, M. M., M. S. Lazera, G. G. Barbosa, L. Trilles, B. R. Balassiano, R. C. Macedo, C. C. Bezerra, M. A. Perez, P. Cardarelli, and B. Wanke. 2003. Serotyping of 467 Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from clinical and environmental sources in Brazil: analysis of host and regional patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:73-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perfect, J. R., and A. Casadevall. 2002. Cryptococcosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 16:837-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toffaletti, D. L., M. Del Poeta, T. H. Rude, F. Dietrich, and J. R. Perfect. 2003. Regulation of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) expression in Cryptococcus neoformans by temperature and host environment. Microbiology 149:1041-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanbreuseghem, R., and M. Takashio. 1970. An atypical strain of Cryptococcus neoformans (San Felice) Vuillemin 1894. II. Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii var. nov. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 50:695-702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varga, J., F. Kevei, A. Vriesema, F. Debets, Z. Kozakiewicz, and J. H. Croft. 1994. Mitochondrial DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms in field isolates of the Aspergillus niger aggregate. Can. J. Microbiol. 40:612-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, L., K. Yokoyama, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 1998. The identification and phylogenetic relationship of pathogenic species of Aspergillus based on the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Med. Mycol. 36:153-164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang, L., K. Yokoyama, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 2000. Mitochondrial cytochrome b gene analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1352-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, L., K. Yokoyama, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 2001. Identification, classification, and phylogeny of the pathogenic species Exophiala jeanselmei and related species by mitochondrial cytochrome b gene analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4462-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, J. 2002. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr. Genet. 41:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu, J., R. Y. Ali, D. A. Gregory, D. Amick, S. E. Lambert, H. J. Yoell, R. J. Vilgalys, and T. G. Mitchell. 2000. Uniparental mitochondrial transmission in sexual crosses in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr. Microbiol. 40:269-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yokoyama, K., S. K. Biswas, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 2000. Identification and phylogenetic relationship of the most common pathogenic Candida species inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4503-4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokoyama, K., L. Wang, M. Miyaji, and K. Nishimura. 2001. Identification, classification and phylogeny of the Aspergillus section Nigri inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200:241-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]