Abstract

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a frequently fatal infection in immunocompromised patients that is difficult to diagnose. Present methods for detection of Aspergillus spp. in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and in tissue vary in sensitivity and specificity. We therefore developed an A. fumigatus-specific quantitative real-time PCR-based assay utilizing fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology. We compared the assay to quantitative culture of BAL fluid and lung tissue in a rabbit model of experimental IPA. Using an enzymatic and high-speed mechanical cell wall disruption protocol, DNA was extracted from samples of BAL fluid and lung tissues from noninfected and A. fumigatus-infected rabbits. A unique primer set amplified internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) 1 and 2 of the rRNA operon. Amplicon was detected using FRET probes targeting a unique region of ITS1. Quantitation of A. fumigatus DNA was achieved by use of external standards. The presence of PCR inhibitors was determined by use of a unique control plasmid. The analytical sensitivity of the assay was ≤10 copies of target DNA. No cross-reactivity occurred with other medically important filamentous fungi. The assay results correlated with pulmonary fungal burden as determined by quantitative culture (r = 0.72, Spearman rank correlation; P ≤ 0.0001). The mean number of genome equivalents detected in untreated animals was 3.86 log10 (range, 0.86 to 6.39 log10) in tissue. There was a 3.53-log10 mean reduction of A. fumigatus genome equivalents in animals treated with amphotericin B (AMB) (95% confidence interval, 3.38 to 3.69 log10; P ≤ 0.0001), which correlated with the reduction of residual fungal burden in lung tissue measured in terms of log10 CFU/gram. The enhanced quantitative sensitivity of the real-time PCR assay was evidenced by detection of A. fumigatus genome in infarcted culture-negative lobes, by a greater number of mean genome equivalents compared to the number of CFU per gram in tissue and BAL fluid, and by superior detection of therapeutic response to AMB in BAL fluid compared to culture. This real-time PCR assay using FRET technology is highly sensitive and specific in detecting A. fumigatus DNA from BAL fluid and lung tissue in experimental IPA.

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a major cause of infectious pneumonic morbidity and mortality of patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation, solid organ transplantation, and treatment for hematological malignancies (12, 16). Although there has been progress in attempts to expedite the diagnosis of IPA (5, 21), prompt diagnosis of this infection remains difficult. Unlike what occurs with many other serious infectious processes, A. fumigatus is virtually never isolated from blood cultures. Clinicians must therefore use other microbiological and radiological diagnostic approaches in cases of IPA. The detection of galactomannan antigen in serum by enzyme immunoassay is an important advance in the detection of invasive aspergillosis (13, 21, 22). However, more recent data demonstrate a lower sensitivity than has been previously reported (9). Definitive diagnosis involves the combination of positive cultures and the demonstration of histological tissue invasion. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is usually performed in lieu of biopsy in immunocompromised patients with pulmonary infiltrates suspicious for IPA. However, the lack of sensitivity of using BAL fluid to detect A. fumigatus in IPA cases has been well documented (19). Consequently, there is a critical need to improve the methodology of detection of A. fumigatus in BAL fluid.

We therefore developed a rapid, quantitative, sensitive, and specific real-time PCR assay using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) technology to detect A. fumigatus. This technology uses two oligonucleotide probes, a donor and an acceptor, each of which is labeled with a different marker dye. These probes are designed to hybridize to adjacent regions of the target amplicon in a head-to-toe manner. When the labeled probes align along the target in a sequence-specific manner, fluorescent energy is transferred from one dye to another to emit a signal in a different wavelength, hence the term FRET. We further validated the assay in a well-established animal model of IPA (6, 17, 24).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model. (i) Rabbits.

Three groups of female New Zealand White rabbits (Hazleton Inc., Deutschland, Pa.) weighing 2.0 to 3.5 kg at the time of inoculation were used in all experiments. Rabbits were individually housed and maintained according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal care and in fulfillment of American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care criteria (15). Vascular access was established in each rabbit by the surgical placement of a silastic tunneled central venous catheter (23). The following groups were studied: (i) untreated rabbits with experimental IPA (n = 10), (ii) rabbits treated with amphotericin B (AMB; 1 mg/kg of body weight/day) (n = 9), and (iii) healthy controls (n = 3).

(ii) Organism and inoculation.

IPA was established as previously described (6). Briefly, A. fumigatus (NIH isolate A. fumigatus 4215, ATCC no. MYA-1163) obtained from a fatal case of pulmonary aspergillosis was used in all experiments. The organism was subcultured from a frozen isolate (stored at −70°C) onto Sabouraud dextrose slants (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The slants were then allowed to grow at room temperature for an additional 5 days before harvesting of conidia. Conidia were harvested under a laminar airflow hood with a solution of 0.025% Tween 20 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, N.J.) in normal saline, transferred to a 50-ml conical tube, washed, and counted in a hemacytometer. The concentration was adjusted in order to give each rabbit a predetermined endotracheal inoculum of 5 × 107 to 1.5 × 108 conidia of A. fumigatus in a volume of 250 to 350 μl. The concentrations of the inocula were confirmed by serial dilution, and culturing was done on 5% Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA) plates. Inoculation was performed intravenously on day 2 of the experiments under general anesthesia with 0.8 to 1.0 ml of a 2:1 (vol/vol) mixture of ketamine (100 mg/ml; Fort Dodge Labs, Fort Dodge, Iowa) and xylazine (20 mg/ml; Mobay Corp., Shawnee, Ky.). Once satisfactory anesthesia was obtained, a Flagg 0 straight-blade laryngoscope (Welch-Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, N.Y.) was inserted until the vocal cords were clearly visualized and the A. fumigatus inocula was administered intratracheally with a tuberculin syringe attached to a 16-gauge, 5[1/4]-inch Teflon catheter (Becton Dickinson, Sandy, Utah).

(iii) Induction, maintenance, and support of neutropenia.

Immunosuppression, neutropenia, and antimicrobial support were conducted as previously described (6, 17). Profound and persistent neutropenia (<100 cells/μl) and thrombocytopenia (30,000 to 50,000 platelets/μl) were sustained throughout the course of infection by cytarabine (AraC) (Cytosar-U; Pharmacia-Upjohn, Kalamazoo, Mich.). Methylprednisolone (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.), at 5 mg/kg of body weight, was administered on days 1 and 2 of the experiments to inhibit macrophage activity against conidia and to facilitate establishment of infection. Ceftazidime (Glaxo, Inc., Research Triangle Park, N.C.), at a dose of 75 mg/kg given intravenously twice daily, gentamicin (Elkins-Sinn, Inc., Cherry Hill, N.J.), and vancomycin (Abbott Laboratories) were administered from day 4 of chemotherapy until study completion for prevention of opportunistic bacterial infections during neutropenia. To prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhea due to Clostridium spiriforme, all rabbits continuously received 50 mg of vancomycin per liter of drinking water. White-blood-cell counts were monitored twice weekly using a Coulter counter (Coulter Corp., Miami, Fla.).

(iv) Treatment groups.

Rabbits were grouped to receive either 1.0 mg of AMB/kg/day or no treatment. Antifungal therapy was initiated on the next day following endotracheal inoculation. AMB (Bristol Myers-Squibb, Princeton, N.J.) was administered slowly (0.1 ml every 10 s) intravenously at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg/day. Therapy was continued throughout the course of the experiments for a maximum of 14 days in surviving rabbits. Rabbits were euthanized by use of intravenous pentobarbital.

(v) Pulmonary lesion scores.

The entire heart-lung block was carefully resected at autopsy. The heart was then dissected away from the lungs, leaving an intact tracheobronchial tree and lung preparation. The lungs were weighed and inspected by at least two observers who were blinded to the treatment group and who recorded hemorrhagic infarct lesions (if any) in each individual lobe.

(vi) Fungal cultures.

Lung tissue in each individual rabbit was sampled and cultured by excision of a representative region of the lung. Each fragment was weighed individually, placed in sterile bags (Tekmar Corp., Cincinnati, Ohio), and homogenized with sterile saline for 15 s per tissue sample (Stomacher 80; Tekmar) (25). Lung homogenates were prepared in sterile saline in 10-fold dilutions of 1:10 and 1:100. Aliquots of 100 μl from homogenates and dilutions were plated onto SGA and incubated at 37°C for the first 24 h and then at room temperature for another 24 h. The CFU of A. fumigatus were counted and recorded for each lobe and the CFU/gram were calculated. An aliquot (1 ml) of each homogenate lung lobe was stored at −20°C for PCR analysis.

(vii) Histopathology.

Representative pulmonary lesions were excised and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff with hematoxylin counterstain and Gomori methenamine silver stains. Tissues were microscopically examined for pulmonary injury and structural changes in Aspergillus hyphae.

(viii) BAL.

BAL was performed on each postmortem resected lung preparation by the instillation and subsequent withdrawal of 10 ml of sterile normal saline into the clamped trachea with a sterile 12-ml syringe. This process was repeated for a total infusion of 20 ml of normal saline. The lavage material was then centrifuged for 10 min at 500 × g. The supernatant was discarded, leaving 2 ml of fluid in which the pellet was then resuspended. A 0.1-ml sample of this fluid and 0.1 ml of dilution (10−1) of this fluid were cultured on SGA plates.

DNA isolation. (i) Lung tissue.

Frozen lung homogenates were thawed at room temperature before extraction was performed. Tissue specimens were initially processed by high-speed mechanical disruption (14). One gram of lysing matrix D (Q•BIOgene, Carlsbad, Calif.) was added to each (1-ml) sample before mechanical disruption in a FastPrep FP 120 instrument (Q•BIOgene). Samples were placed into a FastPrep instrument and processed at speed level 5 for 30 s and placed on ice for 5 min, a process that was repeated three times. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 to 60 s and then gently vortexed. A 100-μl aliquot was taken for further processing. Spheroplasts were formed by adding 100 μl of spheroplast buffer (1.0 M sorbitol, 50.0 mM sodium phosphate monobasic, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mg of lyticase [L-8137; Sigma]/ml) and 10 μl of lysing enzymes (Novozyme [20 mg/ml; L-1412; Sigma]). Samples were mixed well and incubated at 30°C for 1 h at 1,200 rpm in an Eppendorf thermomixer. Following spheroplasting, samples were centrifuged gently at 400 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was removed carefully and discarded without disturbing the pellet. The pellet was processed according to the protocol of the DNeasy Plant kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) with the following modification: after the 200-μl preheated (65°C) AE buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) was applied to the column, the entire apparatus (column and collection tube) was heated at 65°C in the Eppendorf thermomixer for 5 min. A 100-μl aliquot of sterile water was also processed as described above as a control for any contamination from the DNA extraction kit components (kit blank).

(ii) BAL.

Frozen BAL fluid samples were thawed before extraction was performed. Samples were vortexed for 1 min before a 500-μl aliquot was taken for processing. Following centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000 × g, supernatant was discarded and the pellet was gently resuspended in 100 μl of spheroplast buffer and 10 μl of lysing enzymes and incubated at 37°C on a rocking platform for 1 h. After centrifugation for 20 min at 400 × g, the spheroplast-BAL fluid pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of AP1 buffer (DNeasy Plant kit; Qiagen). The sample was added to FastRNA Green tubes (BioPulverizer System I; Q•BIOgene) and processed using the FastPrep instrument (see above). Specimens were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 to 60 s and gently vortexed. The specimen (approximately 300 μl) was transferred to a new tube and adjusted to a volume of 400 μl with AP1 buffer. Four microliters of RNase A (100 mg/ml) was added, and the mixture was vortexed vigorously and incubated for 10 min at 65°C in the thermomixer at 1,200 rpm. The DNeasy Plant kit protocol was followed with the same modification stated above.

Real-time quantitative PCR assay. (i) Primer and probe design.

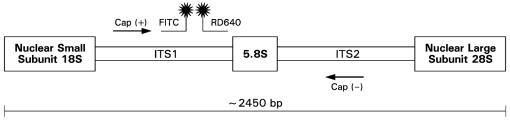

A real-time PCR assay targeting internal transcribed spacer region 1 (ITS1), the 5.8S region, and ITS2 of the rRNA gene complex was designed (Fig. 1). The primers and probes were designed using Oligo software (Molecular Biology Insights, Cascade, Colo.) and purchased from Idaho Technologies (Salt Lake City, Utah). The primers and probes were designed based on a multiple-sequence alignment of rRNA sequences from GenBank by utilizing the Sequencher software package (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.) (Table 1). The National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST database search program was used to determine the uniqueness of the primers and probes for A. fumigatus. The amplicon generated was 253 bp in size.

FIG. 1.

rDNA schematic showing the highly conserved 18S (partial), 5.8S, and 28S (partial) regions with the intervening less-conserved ITS1 and ITS2 regions of A. fumigatus.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences of primers and probes

| Primer or probe | Oligonucleotide sequence | Tm (°C)a |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| Cap (+) sense | 5′ CGA AGA CCC CAA CAT G 3′ | 61.6 |

| Cap (−) sense | 5′ TGA GGG CAG CAA TGA C 3′ | 60.4 |

| Probes | ||

| Cap FITC | 5′ AGT ATG CAG TCT GAG TTG ATT ATC G 3′ | 63.5 |

| Cap RD 640 | 5′ ATC AGT TAA AAC TTT CAA CAA CGG A 3′ | 62.0 |

| Cap RD 705 | 5′ GAT CAT GAC AAG ATT CGC TTC TAA T 3′ | 62.0 |

Tm, melting temperature.

(ii) PCR conditions.

The PCR master mix consisted of 0.5 μM concentrations of each of the primers, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.025% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, Mo.), 0.05 U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.)/ml, PCR 10× buffer (Invitrogen Corp.), 0.2 mM PCR Nucleotide Mix PLUS (1 dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and 3 dUTP in proportionate ratios; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and 0.1 μM concentrations of the fluorescein and LC Red-640 probes. In addition, HK-UNG thermostable uracil N-glycosylase HK-UNG (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.) was utilized as recommended by the manufacturer to prevent potential amplicon carryover. Each reaction mixture contained a 5-μl aliquot of extracted specimen together with 15 μl of the master mix. The cycling conditions were as follows: uracil activation, 37°C, 180 s; uracil heat inactivation, 95°C, 60 s for 1 cycle; denaturation, 95°C, 0 s; annealing, 58°C, 5 s; extension, 72°C, 15 s for 50 cycles. Quantitation standards were run in conjunction with each set of samples. For each rabbit screened (DNA extracted from six lobes/rabbit), the following additional controls were included: (i) DNA extracted from normal lung, (ii) kit blank (water processed through extraction protocol), and (iii) a negative master mix control (water). BAL samples from each rabbit were screened with the following controls: (i) DNA extracted from normal BAL and (ii) a negative master mix control (water).

(iii) Validation of sensitivity and quantitation.

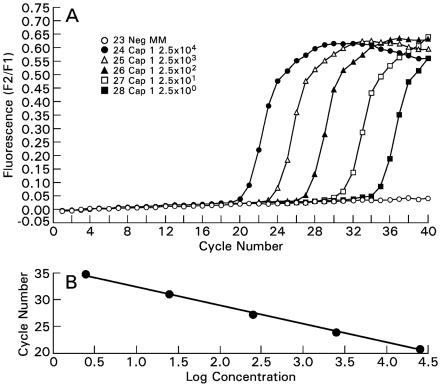

The amplicon generated in the assay was cloned using a TA cloning kit and pCR 2.1 vector (Invitrogen Corp). The pCR 2.1 plasmid with cloned insert was sequenced (ABI 3100 capillary sequencer; Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) to confirm the insertion of a single copy of amplicon. The quantitation, accuracy, and precision of the real-time PCR assay were validated through serial dilutions of the pCR 2.1 plasmid with cloned A. fumigatus rRNA amplicon or gene (Fig. 2). The same plasmid was used as an external quantitation standard in all reaction runs. The conversion from copy number to genome equivalent was based on the estimated number of 100 ribosomal DNA (rDNA) gene complexes in the A. fumigatus genome. For example, a reaction with 1,000 rDNA copies was equivalent to 10 genome equivalents (26). A positive quantitative-PCR signal for BAL was defined as detectable amplification at <36 cycles, particularly in recognition of the fact that a small quantity of Aspergillus conidia or hyphae may be present as background contamination or transient colonization. None of the healthy lungs sampled (n = 19) had a detectable signal. Therefore, a positive quantitative-PCR signal from lung samples was viewed as a true positive, reflecting the presence of A. fumigatus.

FIG. 2.

(A) The wild-type amplicon generated from A. fumigatus genomic DNA was cloned into a pCR 2.1 vector (Invitrogen Corp). The fluorescent signal is proportional to the number of plasmids, ranging from 2.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 100 plasmids. (B) The linear regression line demonstrates both the linearity of the assay and also its efficiency (i.e., the slope) (r = −1.00).

(iv) Specificity: mutated-probe studies.

The Cap RD 640 probe was mutated to create the Cap RD 705 probe, as delineated in Table 1. We demonstrated the specificity of the Cap RD 640 probe by the absence of signal when the Cap RD 705 probe was used instead.

(v) Specificity: cross-reactivity studies.

Cross-reactivity of the assay was assessed by using DNA extracted from Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Pseudallescheria boydii, Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Cryptococcus neoformans, Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium citrinum, Penicillium purpurogenum, and Trichosporon beigelii as well as rabbit DNA and human DNA.

(vi) Inhibition studies.

To confirm the lack of PCR inhibitors from lung tissue and BAL samples, a separate set of PCR-FRET reactions was performed. A unique control plasmid and respective set of primers and probes were designed. A plasmid construct which incorporated a sequence-specific region of the 18S rRNA gene for Candida albicans was designed. This was done to avoid any competition or cross-reaction with potential A. fumigatus DNA in the experimental samples. Primers and probes which would hybridize only to this construct were designed. The presence of inhibitors was checked by comparing the amplification efficiency of this reaction in the extracted samples against those from reactions run with water. Equivalent amplification efficiency compared to reactions run with water reflected the absence of inhibitors. Each lung and BAL sample was tested for inhibitors as described.

RESULTS

Analytical sensitivity and specificity.

The accuracy and precision of the real-time PCR assay were validated through serial dilutions of the newly formed construct containing the A. fumigatus rRNA amplicon or gene. The assay reliably detected ≤10 copies of the pCR 2.1 plasmid per reaction with cloned A. fumigatus rRNA amplicon or gene. The fluorescent signal was proportional to the log concentration of the plasmid (Fig. 2). The calculated PCR efficiency was 1.94. As a measure of interday reproducibility, the coefficient of variation of the PCR assay was 10.1%. The assay did not cross-react with rabbit DNA, human DNA, or DNA from any of the following clinically relevant organisms: Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Pseudallescheria boydii, Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Cryptococcus neoformans, Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium citrinum, Penicillium purpurogenum, and Trichosporon beigelii.

Detection of A. fumigatus in lung tissue.

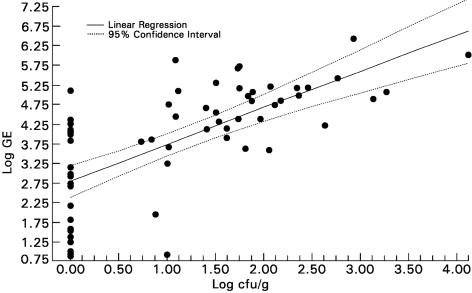

The quantitative real-time PCR assay was more sensitive than culture in detecting A. fumigatus in lung tissue. PCR detected A. fumigatus in infarcted lung tissue in rabbits with experimental IPA in 60 of 60 specimens (100%), compared with 38 of 60 specimens (63.3%) for culture (P < 0.0001). The log genome equivalent of the real-time PCR assay correlated well (r = 0.72; P < 0.0001) with quantitative culture results of lung tissue (log CFU/gram) (Fig. 3). However, the 22 tissues which were culture negative (0 CFU/g) also demonstrated a positive signal for A. fumigatus with log genome equivalents ranging from 0.86 to 5.11. Thus, the real-time PCR assay showed a sensitivity of 100% versus a sensitivity of 63.3% with the standard culture method.

FIG. 3.

Correlation between real-time PCR with FRET technology (log genome equivalent [GE]) and quantitative culture (log10 CFU/gram) in lobes from lungs of untreated rabbits with IPA (r = 0.72, Spearman rank correlation; P ≤ 0.0001).

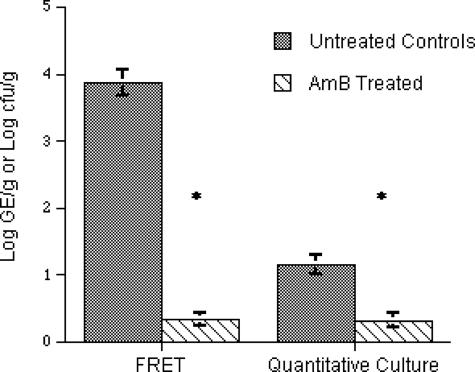

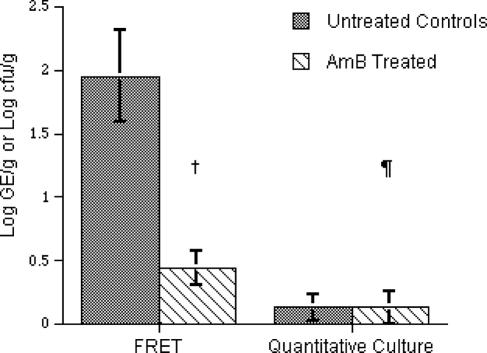

Consistent with this increased sensitivity of detection of A. fumigatus in tissue, the mean log genome equivalent of 3.86 ± 0.19/g of tissue was greater than that of the mean log CFU/gram of culture of A. fumigatus (1.15 ± 0.14) (Fig. 4). Treatment with AMB significantly reduced the residual fungal burden in lung tissue as measured by both quantitative PCR (P < 0.0001) and culture (P < 0.0001).

FIG. 4.

Real-time PCR assay and standard culture assay reflecting efficacy of AMB in lung samples from a rabbit model of IPA. Asterisks indicate P value of ≤0.0001.

Detection of A. fumigatus in BAL fluid.

The relative quantitative relationships between untreated controls and animals treated with AMB were also consistent in BAL fluid when analyzed by real-time PCR. There was a significant decline in detectable signal in treated animals (0.44 ± 0.14 log10 genome equivalents) compared with that in untreated control animals (1.95 ± 0.36 log10 genome equivalents) (P = 0.0005) (Fig. 5). By comparison, the level of detection of A. fumigatus in BAL fluid was low (0.13 ± 0.1 log10 CFU/ml) when measured by culture in untreated controls and not significantly different in comparison to that for treated animals (0.13 ± 0.13 log10 CFU/ml) (P = 0.78). BAL samples from noninfected rabbits were analyzed and found to be negative for A. fumigatus genome at ≤36 cycles in 33 of 34 runs (specificity = 97.1%).

FIG. 5.

Increased sensitivity of real-time PCR assay versus that of standard culture in BAL fluid samples, as reflected by PCR assay showing the efficacy of AMB in experimental IPA. †, P = 0.0005; ¶, P = 0.7805.

DISCUSSION

We developed a sensitive, species-specific, real-time PCR assay for A. fumigatus that was more sensitive than culture in detecting A. fumigatus in BAL fluid from animals with experimental IPA. Although the definitive diagnosis of IPA often requires obtainment of tissue for histology and culture, such procedures are often not feasible in immunocompromised patients. Instead, BAL is much more frequently performed for the diagnosis of IPA. Unfortunately, BAL fluid samples are often culture negative, necessitating lung biopsy or the use of empirical therapy (11). The use of a sensitive and rapid real-time assay, particularly in the case of BAL fluid samples, would be valuable in establishing the diagnosis of IPA. Moreover, the quantitative nature of the assay would assist in decisions regarding the burden of infection and efficacy of therapy in a particular patient. High burdens of infection may signify a more advanced level of infection and a need for aggressive therapy. Also, low fungal burdens that are below the level of detection by culture may be detected by quantitative PCR, thereby avoiding the premature discontinuation of therapy. Beyond its potential clinical utility, this quantitative PCR assay is a useful tool by which to study the pathogenesis and treatment of experimental IPA.

Several key issues regarding the design of assay format, primers, and probes warrant discussion. We purposely avoided the use of a nested PCR approach as a method to increase the sensitivity of the assay because of the major difficulties of amplicon contamination inherent in such a method (10, 20). A nested PCR format also undermines the benefits of the rapid turnaround time associated with the real-time PCR approach.

The rRNA gene was chosen because (i) the multicopy nature of the gene (at least 100 copies per genome) improves the sensitivity of the assay, (ii) A. fumigatus cells separated by septa form a multinucleate hyphal structure (4), thereby increasing the number of copies of the target gene, and (iii) the large amount of sequence data involving this gene complex across many different strains of A. fumigatus and across many different filamentous fungi strengthen the design for a sensitive assay. By utilizing the ITS regions of the complex for primer design, it was possible to develop a species-specific assay while preserving sensitivity. The high specificity of the primers in the assay is critical in the case of nonsterile specimens such as BAL fluid in order to avoid the occurrence of a competing PCR with resultant reduction in sensitivity of A. fumigatus amplification.

In designing the fluorescent probes, a relatively short distance of approximately 1 to 5 bases is initially used in order to allow for fluorescent energy transfer between the marker dyes. By mutating the Cap RD 640 probe to Cap RD 705 (Table 1), we demonstrated its specificity for the regional sequence of the ITS1 gene of A. fumigatus.

The FRET assay detected ≤10 copies of A. fumigatus rRNA gene per reaction. The assay was also highly specific, as shown by the lack of cross-reactivity with other species of fungi and bacteria. A wide linear range that extended out to 6 to 7 orders of magnitude was demonstrated.

The quantitative PCR assay was more sensitive than culture, detecting nearly 1,000-fold more genome equivalents in lung tissue of nontreated animals. Culture detected only a 10-fold difference. A similar pattern is seen in BAL. This increased sensitivity presumably represented a combination of both free A. fumigatus DNA and nonviable fungal elements in untreated lung tissues and BAL fluid. The assay detected 100 copies of A. fumigatus rDNA (equivalent to one nucleus) per 10 mg of lung tissue. Such a finding correlates with our measured extraction efficiencies (see below).

Although not within the scope of the experiments reported here, the enhanced sensitivity of the quantitative PCR assay compared to that of culture may translate into earlier detection. To test this hypothesis, a separate series of experiments could be designed to perform BAL on rabbits at designated time points. The yield of quantitative PCR versus that of culture of BAL could then be compared.

An internal inhibition control was incorporated into the assay during its development. This permitted an assessment of the presence or absence of inhibitors in the tissue and BAL DNA extracts. Inhibitors were not demonstrated in lung tissue or BAL fluid.

A number of different fungal DNA extraction methods were initially assessed. These included the IsoQuick procedure (Orca Research Inc., Bothwell, Wash.), Clontech's (Palo Alto, Calif.) DNA extraction kit, and Qiagen's DNeasy Tissue and DNeasy Plant kits. For the lung tissue samples, the method that yielded the highest DNA extraction efficiency was homogenization with chaotropic high-speed disruption with lytic matrices (HSCD/LM), followed by lyticase treatment (14) and subsequent processing with the DNeasy Plant kit. For the BAL fluid samples, the optimal approach involved using lyticase followed by HSCD/LM, which was followed by the DNeasy Plant kit. To highlight the difficulties encountered in fungal DNA extraction, we calculated that for A. fumigatus conidia no method assessed yielded more than 0.1% of fungal DNA, with most yielding significantly less, consistent with previous extraction reports (7, 14).

All tissue samples from infected animals had hemorrhagic infarcts or resolving infarct lesions, which correlate histologically with the presence of angioinvasive fungal infection (1). Hence, the negative culture but positive PCR is not a false-positive reaction but rather an indication of the greater sensitivity of the PCR assay. These experimental observations also correlate with the clinical observation that biopsies from patients that demonstrate histologically documented hyphal invasion by fungi morphologically compatible with Aspergillus spp. may be negative by culture.

We demonstrated a very clear effect of treatment with AMB in this animal model of IPA. For BAL fluid specimens, we found a mean reduction of 1.51 log10 expressed as genome equivalents. The reduction in tissue specimens was more marked at 3.53 log10, suggesting that the AMB is more effective in tissue than in the bronchial mucosa, presumably secondary to the respective drug levels. Another possibility is that the assay may have detected some of the original conidia inoculated but not cleared by AMB.

Although several studies have applied nonquantitative PCR assays to human BAL specimens (2, 3, 8, 18), this is to our knowledge the first report of the application of quantitative PCR for the detection of experimental IPA. Moreover, we have characterized and validated the assay in a well-defined model of experimental IPA, where variables of immunosuppression, tissue burden, and therapy may be rigorously controlled. This approach to characterization and validation of the PCR assay provides a strong quantitative foundation for understanding data generated from its application to specimens of BAL fluid from humans.

In summary, we have developed and validated a quantitative real-time PCR assay to detect A. fumigatus. The assay is sensitive and specific and easily demonstrates the effect of AMB in the animal model of IPA. Assessment of the assay using human specimens is presently ongoing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berenguer, J., M. C. Allende, J. W. Lee, K. Garrett, C. Lyman, N. M. Ali, J. Bacher, P. A. Pizzo, and T. J. Walsh. 1995. Pathogenesis of pulmonary aspergillosis. Granulocytopenia versus cyclosporine and methylprednisolone-induced immunosuppression. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 152:1079-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchheidt, D., C. Baust, H. Skladny, M. Baldus, S. Brauninger, and R. Hehlmann. 2002. Clinical evaluation of a polymerase chain reaction assay to detect Aspergillus species in bronchoalveolar lavage samples of neutropenic patients. Br. J. Haematol. 116:803-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchheidt, D., C. Baust, H. Skladny, J. Ritter, T. Suedhoff, M. Baldus, W. Seifarth, C. Leib-Moesch, and R. Hehlmann. 2001. Detection of Aspergillus species in blood and bronchoalveolar lavage samples from immunocompromised patients by means of 2-step polymerase chain reaction: clinical results. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:428-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnett, J. H. 1975. Mycogenetics: an introduction to the general genetics of fungi. John Wiley & Sons, London, England.

- 5.Caillot, D., O. Casasnovas, A. Bernard, J. F. Couaillier, C. Durand, B. Cuisenier, E. Solary, F. Piard, T. Petrella, A. Bonnin, G. Couillault, M. Dumas, and H. Guy. 1997. Improved management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients using early thoracic computed tomographic scan and surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 15:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francis, P., J. W. Lee, A. Hoffman, J. Peter, A. Francesconi, J. Bacher, J. Shelhamer, P. A. Pizzo, and T. J. Walsh. 1994. Efficacy of unilamellar liposomal amphotericin B in treatment of pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently granulocytopenic rabbits: the potential role of bronchoalveolar d-mannitol and serum galactomannan as markers of infection. J. Infect. Dis. 169:356-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haugland, R. A., J. L. Heckman, and L. J. Wymer. 1999. Evaluation of different methods for the extraction of DNA from fungal conidia by quantitative competitive PCR analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 37:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayette, M. P., D. Vaira, F. Susin, P. Boland, G. Christiaens, P. Melin, and P. De Mol. 2001. Detection of Aspergillus species DNA by PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2338-2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbrecht, R., V. Letscher-Bru, C. Oprea, B. Lioure, J. Waller, F. Campos, O. Villard, K. L. Liu, S. Natarajan-Ame, P. Lutz, P. Dufour, J. P. Bergerat, and E. Candolfi. 2002. Aspergillus galactomannan detection in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 20:1898-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawamura, S., S. Maesaki, T. Noda, Y. Hirakata, K. Tomono, T. Tashiro, and S. Kohno. 1999. Comparison between PCR and detection of antigen in sera for diagnosis of pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:218-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latge, J. P. 1999. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:310-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lortholary, O., S. Ascioglu, P. Moreau, R. Herbrecht, A. Marinus, P. Casassus, B. De Pauw, and D. W. Denning for the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. 2000. Invasive aspergillosis as an opportunistic infection in nonallografted patients with multiple myeloma: a European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maertens, J., J. Verhaegen, H. Demuynck, P. Brock, G. Verhoef, P. Vandenberghe, J. Van Eldere, L. Verbist, and M. Boogaerts. 1999. Autopsy-controlled prospective evaluation of serial screening for circulating galactomannan by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hematological patients at risk for invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3223-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller, F. M., K. E. Werner, M. Kasai, A. Francesconi, S. J. Chanock, and T. J. Walsh. 1998. Rapid extraction of genomic DNA from medically important yeasts and filamentous fungi by high-speed cell disruption. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1625-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Research Council. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Paterson, D. L., and N. Singh. 1999. Invasive aspergillosis in transplant recipients. Medicine (Baltimore) 78:123-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petraitiene, R., V. Petraitis, A. H. Groll, T. Sein, R. L. Schaufele, A. Francesconi, J. Bacher, N. A. Avila, and T. J. Walsh. 2002. Antifungal efficacy of caspofungin (MK-0991) in experimental pulmonary aspergillosis in persistently neutropenic rabbits: pharmacokinetics, drug disposition, and relationship to galactomannan antigenemia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raad, I., H. Hanna, A. Huaringa, D. Sumoza, R. Hachem, and M. Albitar. 2002. Diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis using polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Aspergillus in BAL. Chest 121:1171-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito, H., E. J. Anaissie, R. C. Morice, R. Dekmezian, and G. P. Bodey. 1988. Bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of pulmonary infiltrates in patients with acute leukemia. Chest 94:745-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skladny, H., D. Buchheidt, C. Baust, F. Krieg-Schneider, W. Seifarth, C. Leib-Mosch, and R. Hehlmann. 1999. Specific detection of Aspergillus species in blood and bronchoalveolar lavage samples of immunocompromised patients by two-step PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3865-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stynen, D., A. Goris, J. Sarfati, and J. P. Latge. 1995. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:497-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verweij, P. E., Z. Erjavec, W. Sluiters, W. Goessens, M. Rozenberg-Arska, Y. J. Debets-Ossenkopp, H. F. Guiot, and J. F. Meis for the Dutch Inter-university Working Party for Invasive Mycoses. 1998. Detection of antigen in sera of patients with invasive aspergillosis: intra- and interlaboratory reproducibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1612-1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh, T. J., J. Bacher, and P. A. Pizzo. 1988. Chronic silastic central venous catheterization for induction, maintenance and support of persistent granulocytopenia in rabbits. Lab. Anim. Sci. 38:467-471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh, T. J., K. Garrett, E. Feurerstein, M. Girton, M. Allende, J. Bacher, A. Francesconi, R. Schaufele, and P. A. Pizzo. 1995. Therapeutic monitoring of experimental invasive pulmonary aspergillosis by ultrafast computerized tomography, a novel, noninvasive method for measuring responses to antifungal therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1065-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh, T. J., C. McEntee, and D. M. Dixon. 1987. Tissue homogenization with sterile reinforced polyethylene bags for quantitative culture of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:931-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warner, J. R. 1989. Synthesis of ribosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 53:256-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]