Abstract

A concise second-generation total synthesis of the fungal-derived alkaloid (+)-gliocladin C (11), in ten steps and 11% overall yield from isatin, is reported. In addition, the ETP natural product (+)-gliocladine C (6) is prepared in six steps and 29% yield from the di-(tert-butoxycarbonyl) precursor of 11. The total synthesis of (+)-gliocladine C (6) constitutes the first total synthesis of an ETP natural product containing a hydroxyl substituent adjacent to a quaternary carbon stereocenter in the pyrrolidine ring.

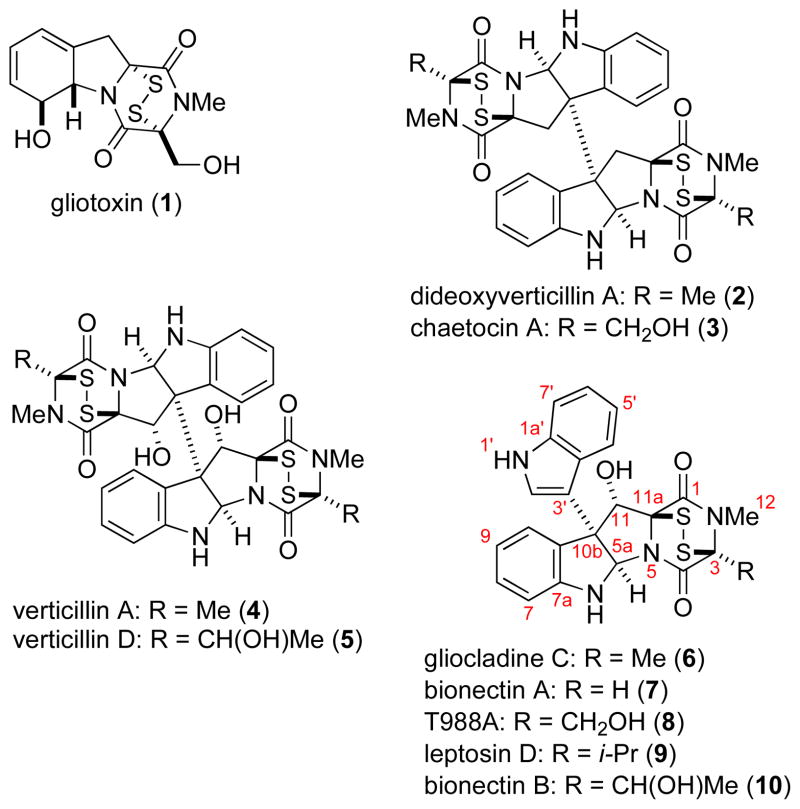

Epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) toxins are fungal secondary metabolites that possess unique molecular structures and a wide range of biological activities (Figure 1).1 The toxicity of these amino acid-derived natural products is attributed to the di- or polysulfide bridge of the dioxopiperazine subunit, which either can directly conjugate to cysteine residues or generate reactive oxygen species. A number of recent studies point to the potential utility of epidithiodioxopiperazines in cancer chemotherapy,2 as impressive selectivity towards both myeloma3 and solid tumors4 has been demonstrated and novel molecular targets have been identified.5 The structure and chemical lability of epipolythiodioxopiperazines pose a number of challenges for chemical synthesis. In a remarkable accomplishment, Fukuyama and Kishi disclosed the total synthesis of gliotoxin (1) in 1976,6 with the chemistry developed in these investigations for incorporating an epidithiodioxopiperazine unit7 being subsequently used for the synthesis of various other ETP natural products.8 In an incisive total synthesis of dideoxyverticillin A (2) reported in 2009 by Movassaghi and co-workers, biosynthetically inspired oxidation of cyclotryptamine-fused dioxopiperazines and sulfidation was employed to elaborate epidithio bridges onto dimeric dioxopiperazine precursors.9,10 Shortly thereafter, Sodeoka and co-workers reported the synthesis of (+)-chaetocin A (3) using a related strategy for forging the epidithiodioxopiperazine units.11

Figure 1.

Some ETP natural products.

The largest group of ETP natural products is derived from tryptophan and contains an ETP ring fused to a cyclotryptamine fragment. (Figure 1).1 In many of these structures, the carbon of the pyrrolidine ring adjacent to the quaternary carbon stereocenter bears a hydroxyl substituent (e.g., 4–10, Figure 1). Herein we disclose a general approach for preparing ETPs having this highly labile hydroxyl substituent,12 which we illustrate by an enantioselective total synthesis of gliocladine C (6).13,14 Critical to our success was the development of a new convergent method for constructing cyclotryptamine-fused polyoxopiperazines.

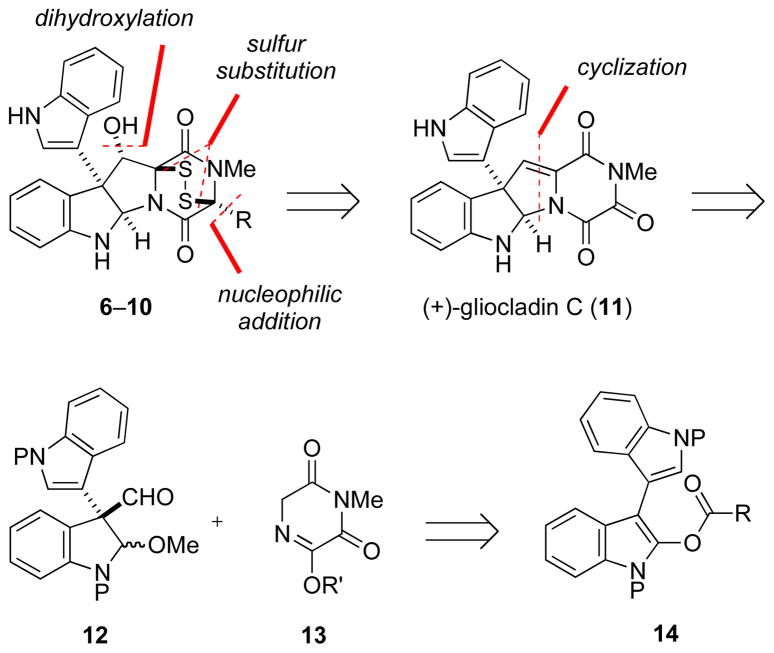

Our approach for preparing (+)-gliocladine C (6) and congeners is outlined in Scheme 1. We hypothesized that the simpler alkaloid (+)-gliocladin C (11)15 might serve as a synthetic precursor of this family of ETPs by three potentially straightforward transformations: i) nucleophilic addition of a C3 substituent16 to the α-ketoimide carbonyl group, ii) dihydroxylation of the alkylidene dioxopiperazine double bond, and iii) disulfide bridge formation.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis of ETPs 6–10

The opening phase of this endeavor was the development of an efficient second-generation total synthesis of (+)-gliocladin C (11), whose first total synthesis was reported from our laboratory in 2007.12 Our plan was to assemble the tetracyclic core of (+)-gliocladin C from the union of enantioenriched dielectrophile 12 and dinucleophile 13,17 with the quaternary carbon stereocenter of the former arising from catalytic enantioselective Steglich-type rearrangement of indolyl carbonate 14.18,19

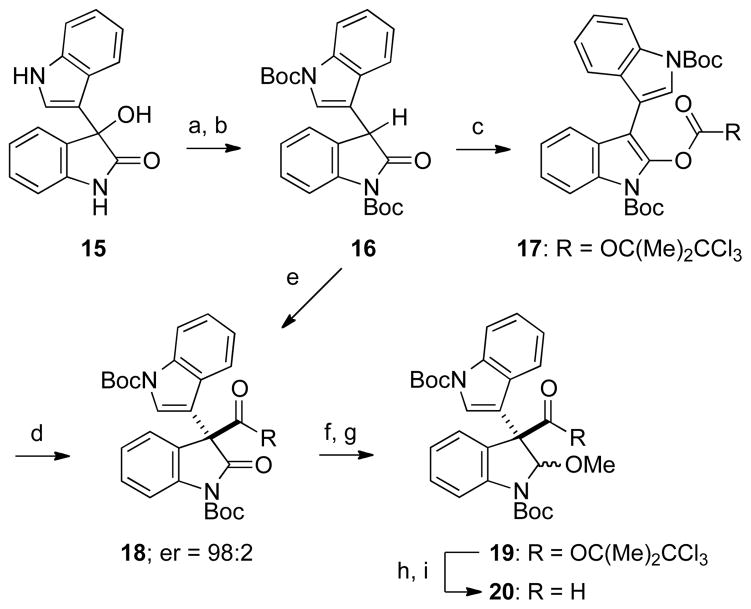

The synthesis of (+)-gliocladin C commenced with acid-promoted ionic reduction of readily available 3-hydroxy-3,3′-biindolin-2-one 15,20 followed by Boc protection to give intermediate 16 (Scheme 2).21 Reaction of oxindole 16 with 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate and Et3N delivered prochiral indolyl carbonate 17 in 66% overall yield from biindolinone 15. Catalytic rearrangement of 17 took place efficiently and with high enantioselectivity at room temperature in the presence of 5 mol % of Fu’s (S)-(−)-4-pyrrolidinopyrindinyl(pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)iron catalyst19a to give 3,3-disubstituted oxindole 18 in 96% yield and a 98:2 enantiomer ratio (er) on scales up to 15 g. In addition, direct reaction of oxindole 16 with 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethyl chloroformate, Et3N, and 10 mol % of Fu’s catalyst at 40 °C provided oxindole ester 18 in 88% yield and identical high enantioselectivity (er = 98:2).

Scheme 2.

Preparation of Enantioenriched Dielectrophile 20a

a Reaction conditions: (a) TFA, Et3SiH, CH2Cl2, rt; (b) i. (Boc) 2O, 15 mol % DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt; ii. MeOH (68% from 15); (c) 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethylchloroformate, Et3N, THF, 0 °C (97%); (d) (S)-(−)-4-pyrrolidinopyridinyl(pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)-iron, THF, rt (96%, 98:2 er); (e) 2,2,2-trichloro-1,1-dimethylethylchloroformate, Et3N, (S)-(−)-4-pyrrolidinopyridinyl(pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)iron, THF, 40 °C (88%, 98:2 er); (f) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C (81%); (g) HC(OMe) 3, 10 mol % PPTS, MeOH, 65 °C (83%; 1.2:1.0 dr); (h) LiBH4–MeOH, Et2O, rt to 40 °C (84%); (i) Dess–Martin periodinane, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt (95%).

After several shorter approaches proved inefficient or resulted in partial racemization,22 oxindole 18 was elaborated to indoline 20 in good yield as follows. The oxindole carbonyl group of 18 was reduced selectively with NaBH4 at 0 °C, and the resulting 2-hydroxyindoline intermediate was exposed to a methanolic solution of trimethyl orthoformate and a catalytic amount of pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) at 65 °C to afford indoline N,O-acetal 19, a 1.2:1.0 mixture of α and β-N,O-acetal epimers, in 67% overall yield. Sequential Soai reduction,23 and Dess–Martin oxidation24 provided enantioenriched dielectrophile 20 in 80% yield from 19.

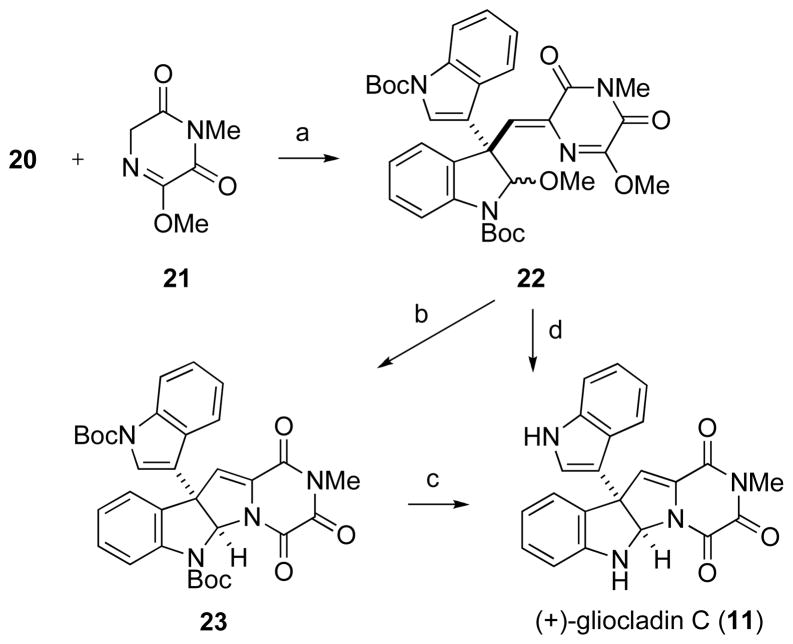

In two additional steps, indoline aldehyde 20 was united with trioxopiperazine derivative 21 to provide (+)-gliocladin C (11) (Scheme 3). Aldol condensation of aldehyde 20 with the lithium enolate of piperazinedione 2125 in THF at −78 °C, followed by quenching the reaction with excess acetic acid and warming to room temperature delivered condensation product 22, as exclusively the Z stereoisomer, in 75% yield. Exposure of 22 to BF3·OEt2 at −40 °C promoted cyclization and concomitant demethylation to provide trioxopiperazine-fused cyclotryptamine 23 in 80% yield. The Boc protecting groups of 23 were then removed thermolytically26 to afford crystalline (+)-gliocladin C (11) in 89% yield. Alternately, coupled intermediate 22 could be transformed directly to (+)-gliocladin C (11), [α]23D +127 (c 0.23, pyridine),27 in 60% yield upon reaction with excess Sc(OTf)3 in acetonitrile at 0 °C to room temperature. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction of synthetic (+)-gliocladin C (11) confirmed the constitution and relative configuration of this natural product.28

Scheme 3.

Second-Generation Synthesis of (+)-Gliocladin C (11)a

a Reaction conditions: (a) i. LDA, 21, THF, −78 °C; ii. 20, −78 °C; iii. AcOH, −78 °C to rt (75% from 20); (b) BF3·OEt2, CH2Cl2, −78 to −40 °C (80%); (c) neat, 175 °C (89%); (d) Sc(OTf) 3, MeCN, 0 °C to rt (60%).

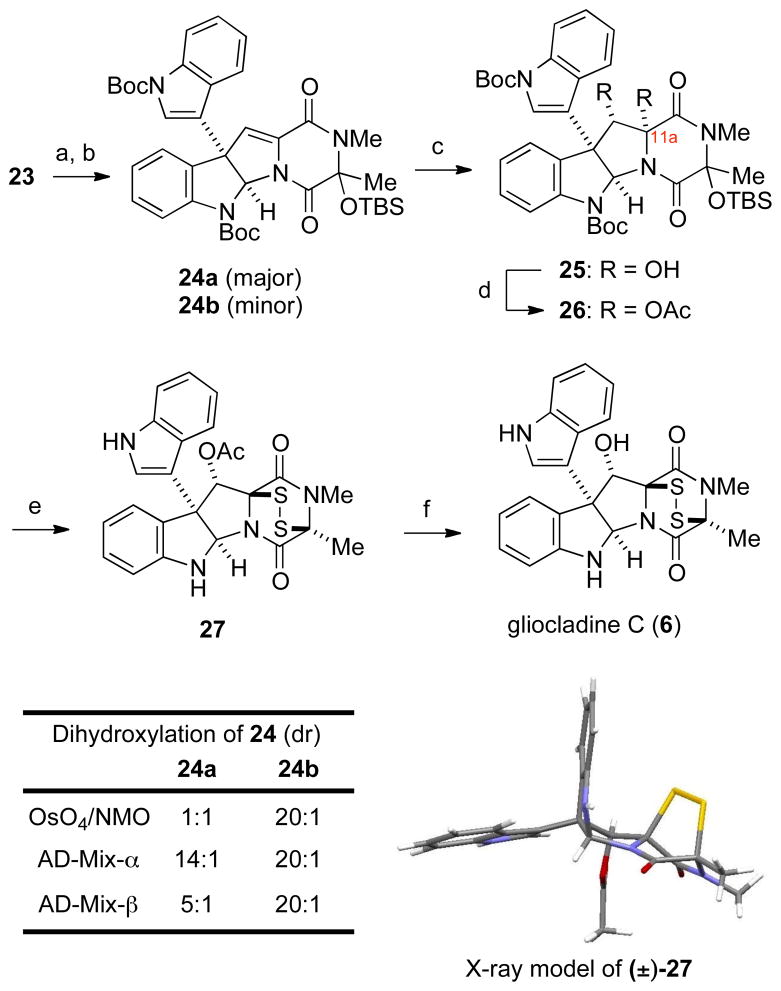

With substantial quantities of trioxopiperazine-fused pyrrolidinoindoline 23 in hand, we turned to its transformation to (+)-gliocladine C (6) (Scheme 4). Chemoselective addition29 of methylmagnesium chloride to trioxopiperazine 23 at −78 °C provided a 9:1 mixture of epimeric tertiary alcohols, which was silylated to give dioxopiperazine 24, a 3:2 mixture of siloxy epimers, in 81% overall yield. Although it was most convenient to prepare ETP product 27 directly from this mixture of stereoisomers (see below), insight into the dihydroxylation step was obtained when epimers 24a and 24b were separated and individually examined. As summarized in Scheme 4, catalytic dihydroxylation of the minor siloxy epimers was highly substrate controlled yielding α diol 25 with 20:1 diasteroselectivity using OsO4/NMO, AD-Mix-α or AD-Mix-β.30 Although no diasteroselectivity was observed in dihydroxylation of the major epimer 24a with OsO4, diastereoselection in forming the α-diol product was improved to 14:1 using AD-Mix-α. Employing this oxidant, the initially produced 3:2 mixture of siloxy epimers 24 was dihydroxylated and the crude diol products acetylated to provide diacetates 26 in 76% yield over the two steps.30b,31 Reaction of this mixture of siloxy epimers with condensed hydrogen sulfide and BF3·OEt2 in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C to room temperature,32 followed by exposure of the product to oxygen, delivered ETP product 27 in 62% yield.33,34 We speculate that stereoselection in this step is the result of initial iminium ion formation at C11a, followed by kinetically controlled trapping with H2S from the face opposite both the angular indolyl substituent and the adjacent acetate.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (+)-Gliocladine C (6)a

a Reaction conditions: (a) MeMgCl, THF, −78 ºC (86%, 9:1 dr); (b) TBSOTf, DMAP, Et3N, DMF, rt (94%, 3:2 dr); (c) mixture of 24a and 24b (3:2), AD-Mix-α, H2NSO2Me, K2OsO4·2H2O, (DHQ) 2PHAL, t-BuOH/H2O/acetone, rt (82%, >14:1 dr); (d) Ac 2O, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt (93%); (e) i. H2S, BF3·OEt 2, CH2Cl2, −78 ºC to rt; ii. O2, MeOH/EtOAc, rt (62%); (f) La(OTf)3, MeOH, 40 ºC (75%).

At this stage, all that remained was removal of the acetate and this transformation was accomplished by heating ETP intermediate 27 in a methanolic solution of La(OTf)3 at 40 °C,35 which gave (+)-gliocladine C (6) as a colorless amorphous solid in 75% yield. The optical rotation of synthetic 6, [α]23D +505 (c 0.47 pyridine), compared well with the value reported for the natural sample, [α]18.7D +513 (c 0.33, pyridine), as did spectroscopic data.

In conclusion, the total synthesis of (+)-gliocladine C (6) constitutes the first total synthesis of an ETP natural product containing hydroxy substitution in the pyrrolidine ring. Moreover, the total syntheses of (+)-gliocladin C (11) and (+)-gliocladine C (6) disclosed herein showcase two short synthetic sequences that we expect will find broader utility. First, the assembly of (+)-gliocladin C (11) from enantioenriched aminal aldehyde 20 and dioxopiperazine derivative 21 illustrates a convergent construction of oxopiperazine-fused pyrrolidinoindolines that can be employed to access more widely distributed dioxopiperazine variants. Second, the construction of epidithiodioxopiperazine alkaloid (+)-gliocladine C (6) from trioxopiperazine precursor 23 illustrates a sequence wherein diversity in the dioxopiperazine unit of an ETP product can be introduced at a late stage in a synthetic sequence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support from the NIH National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (GM-30859) and postdoctoral fellowship support to JED (GM090473), SMM (GM082113), and FLZ (Swiss NSF) is gratefully acknowledged. NMR and mass spectra were determined at UC Irvine using instruments purchased with the assistance of NSF and NIH shared instrumentation grants. We thank Dr. Joseph Ziller and Dr. John Greaves, Department of Chemistry, UC Irvine, for their assistance with X-ray and mass spectrometric analyses.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, characterization data, copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of new compounds, and full citation of reference 4b. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ. Microbiology. 2005;151:1021–1032. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Waring P, Eichner RD, Müllbacher A. Med Res Rev. 1988;8:499–524. doi: 10.1002/med.2610080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review, see: Chai CL, Waring P. Redox Rep. 2000;5:257–264. doi: 10.1179/135100000101535799.

- 3.(a) Erkel G, Gehrt A, Anke T, Sterner O. Z Naturforsch. 2002;57C:759–767. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-7-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Isham CR, Tibodeau JD, Jin W, Xu R, Timm MM, Bible KC. Blood. 2007;109:2579–2588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-027326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Vigushin DM, Mirsaidi N, Brooke G, Sun C, Pace P, Inham L, Moody CJ, Coombes RC. Med Oncol. 2004;21:21–30. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:1:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kung AL, et al. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee Y-M, Lim J-H, Yoon H, Chun Y-S, Park JW. Hepatology. 2011;53:171–180. doi: 10.1002/hep.24010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Griner D, Bonaldi T, Eskeland R, Roemer E, Imhof A. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:143–145. doi: 10.1038/nchembio721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Block KM, Wang H, Szabo LZ, Polaske NW, Henchey LK, Dubey R, Kushal S, Laszlo CF, Makhoul J, Song Z, Meuillet EJ, Olenyuk BZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18078–18088. doi: 10.1021/ja807601b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cook KM, Hilton ST, Mecinovic J, Motherwell WB, Figg WD, Schofield CJ. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26831–26838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tibodeau JD, Benson LM, Isham CR, Owen WG, Bible KC. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1097–1106. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2318. and refs 4a–4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuyama T, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:6723–6723. doi: 10.1021/ja00437a063.Full account, see: Fukuyama T, Nakatsuka S-I, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2045–2078.

- 7.Kishi Y, Fukuyama T, Nakatsuka S. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:6490–6491. doi: 10.1021/ja00800a078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kishi Y, Fukuyama T, Nakatsuka S. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:6492–6493. doi: 10.1021/ja00800a078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kishi Y, Nakatsuka S, Fukuyama T, Havel M. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:6493–6495. doi: 10.1021/ja00800a079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu Z, Williams LJ, Danishefsky SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3866–3868. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3866::AID-ANIE3866>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Ashenhurst JA, Movassaghi M. Science. 2009;324:238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1170777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Movassaghi group recently disclosed a strategy for introduction of multiple sulfur atoms culminating in the total synthesis of the dimeric epitri- and epitetradioxopiperazine alkaloids, (+)-chaetocin C and (+)-11,11′-dideoxychetracin A, see: Kim J, Movassaghi M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14376–14378. doi: 10.1021/ja106869s.

- Iwasa E, Hamashima Y, Fujishiro S, Higuchi E, Ito A, Yoshida M, Sodeoka M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4078–4079. doi: 10.1021/ja101280p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overman LE, Shin Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:339–341. doi: 10.1021/ol062801y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J-Y, He H-P, Shen Y-M, Zhang K-Q. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1510–1513. doi: 10.1021/np0502241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cytotoxicity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus and quinolone-resistant S. aureus in addition to nematicidal activity have been reported for the gliocladines.13

- 15.Usami Y, Yamaguchi J, Numata A. Heterocycles. 2004;63:1123–1129.Gliocladin C was recently isolated from a terrestrial fungus, see: Bertinetti BV, Rodriguez MA, Godeas AM, Cabrera GM. J Antibiot. 2010;63:681–683. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.103.

- 16.The numbering system for gliocladine C used by Zhang and coworkers is employed.13 For a discussion of the various positional numbering systems used in this area, see p S3 of ref 9.

- 17.For the reverse approach wherein the dielectrophile is achiral and the dinucleophile chiral, see ref. 8b.

- 18.Steglich W, Höfle G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;11:4727–4730. [Google Scholar]

- 19.For pioneering studies of asymmetric carboxyl migrations of oxindole-derived enoxycarbonates, see: Hills ID, Fu GC. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:3921–3924. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351666.Shaw SA, Aleman P, Vedejs E. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13368–13369. doi: 10.1021/ja037223k.Shaw SA, Aleman P, Christy J, Kampf JW, Va P, Vedejs E. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:925–934. doi: 10.1021/ja056150x.

- 20.3-Hydroxy-3,3′-biindolin-2-one 15 was prepared in 75% yield from the reaction of isatin and indole: Bergman J. Acta Chem Scand. 1971;25:1277–1280.

- 21.(a) Rajeswaran WG, Cohen LA. Tetrahdedron. 1998;54:11375–11380. [Google Scholar]; (b) Porcs-Makkay M, Argay G, Kálmán A, Simig G. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:5893–5903. [Google Scholar]

- 22.For example, global reduction of 18 could be accomplished with several reducing agents (i.e., LiBH4, NaBH4, LiAlH4) to afford the 3-hydroxymethyl-2-hydroxyindoline intermediates. However, these reactions resulted in partial racemization of the quaternary carbon stereocenter, presumably at the stage of a 3-formyl-2-hydroxyindoline intermediate; see: Dmitrienko GI, Denhart D, Mithani S, Prasad GKB, Taylor NJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5705–5708.Ziegler FE, Belema M. J Org Chem. 1997;62:1083–1094.

- 23.Soai K, Ookawa A. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4000–4005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dess DB, Martin JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7277–7287. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Readily prepared from glycine N-methylamide hydrochloride; see the Supporting Information for details.

- 26.Rawal VH, Jones RJ, Cava MP. J Org Chem. 1987;52:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The reported optical rotation for the natural product is [α]16D +131.4 (c 0.07, CHCl3).15a We observed limited solubility for synthetic crystalline (+)-gliocladin C in CHCl3; as a result, we could obtain rotation data in this solvent only under dilute conditions: [α]23D +113 (c 0.0093, CHCl3).

- 28.CCDC 814556. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif

- 29.Person D, Le Corre M. Bull Soc Chim Fr. 1989;5:673–676. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hentges SG, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4263–4265.(b) Additional K2OsO4·2H2O and (DHQ) 2PHAL (or (DHQD) 2PHAL) were added as dihydroxylation of this hindered double bond is slow.

- 31.After purification, this product contained approximately 5% of the β-diols.

- 32.For an early construction of epidithiodioxopiperazines from the acid-promoted reaction of H2S with dioxopiperazines having leaving groups at C3 and C6, see Ottenheijm HCJ, Kerkhoff GPC, Bijen JWHA. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1975:768–769.

- 33.The relative configuration of this product was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction of the corresponding racemate, CCDC 814557.

- 34.Preparation of gliocladine C directly from diol precursor 25 is problematic as a result of the acid sensitivity of C11-hydroxylated pyrrolidinoindolines.12

- 35.Overman LE, Sato T. Org Lett. 2007;9:5267–5270. doi: 10.1021/ol702518t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.