Abstract

Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L., Clusiaceae) is a popular botanical dietary supplement in the United States, where it is used principally as an antioxidant. It is referred to as the “queen of fruits” in Thailand, a country of origin. The major secondary metabolites of mangosteen, the xanthones, exhibit a variety of biological activities including antibacterial, antifungal, antiinflammatory, antioxidant, antiplasmodial, cytotoxic, and potential cancer chemopreventive activities. Moreover, some of the xanthones from mangosteen have been found to influence specific enzyme activities, such as aromatase, HIV-1 protease, inhibitor κB kinase, quinone reductase, sphingomyelinase, topoisomerase and several protein kinases, and they also modulate histamine H1 and 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor binding. Several synthetic procedures for active xanthones and their analogs have been conducted to obtain a better insight into structure-activity relationships for this compound class. This short review deals with progress made in the structural characterization of the chemical constituents of mangosteen, as well as the biological activity of pure constituents of this species and synthetic methods for the mangosteen xanthones.

INTRODUCTION

Garcinia mangostana L. (Clusiaceae) is commonly known as mangosteen and “mangkhut”, and its fruits are referred to in Thailand as the “queen of fruits”, as a result of its delicious taste [1,2]. The mangosteen plant grows slowly to 7–12 m high, and has a straight trunk and dark brown bark. It is cultivated principally in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The purple ripe fruits consist of 6–8 seeds, and have a white and juicy pulp [1]. The fruits of G. mangostana have been used as a traditional medicine in southeastern Asia for the treatment of diarrhea, dysentery, inflammation, and ulcers, as well as for wound healing [1,2]. In the United States, mangosteen products are now widely available and are highly popular because of their perceived role in promoting human health [3]. Mangosteen fruit juice was ranked as one of the top three-selling “single botanicals” on the U.S. market in 2007 [4]. Mangosteen extracts and purified constituents have been subjected to a wide array of biological tests germane particularly to infectious diseases, cancer chemotherapy and cancer chemoprevention, diabetes, and neurological conditions [1,2,5–8]. This contribution summarizes studies reported on the structural characterization of the chemical constituents of G. mangostana, and the biological activity of the main secondary metabolites of this species, followed by the chemical synthesis of several mangosteen xanthones.

CHARACTERIZATION OF SECONDARY METABOLITES FROM G. MANGOSTANA

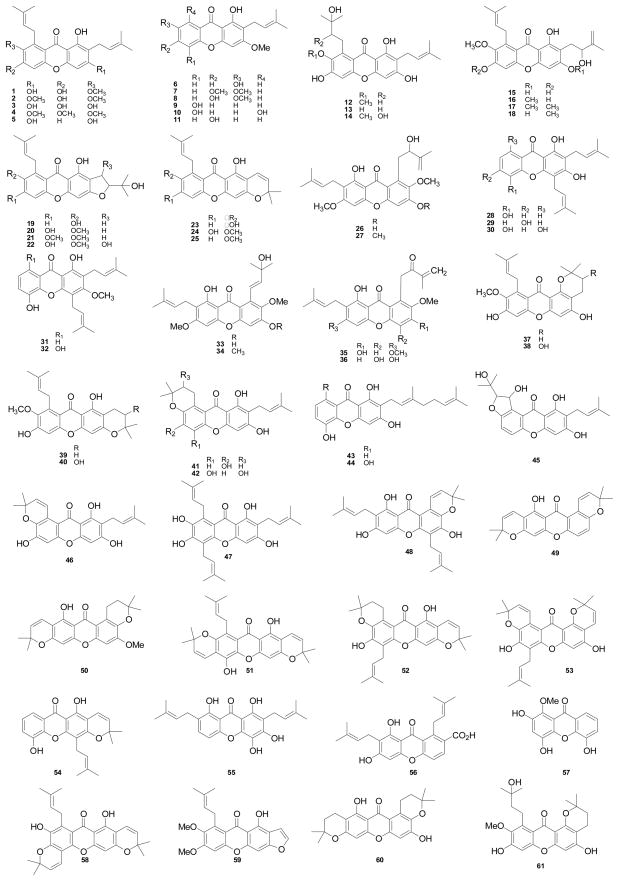

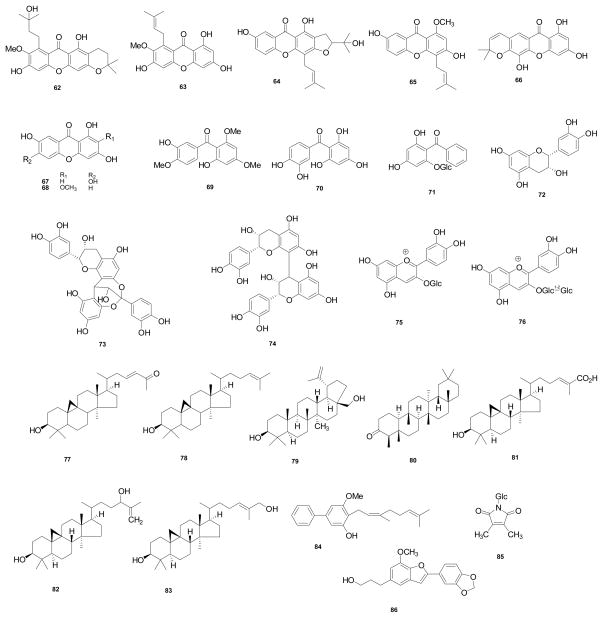

According to a report published in 1958 [9], α-mangostin was first isolated from the dried skin of G. mangostana fruits in 1855 by W. Schmid. Early efforts to assign the structure of α-mangostin (1) relied on the analysis of chemically degraded fragments (acetic acid, amyl alcohol, α-hydroxybutyric acid, isocaproic acid, isovaleric acid, 3,5-dihydroxy-2-methoxyisopentenylbenzene, 2-methyl-2-hepten-6-ol, oxalic acid, and phloroglucinol). This work was conducted by several chemists, including Dragendorff, Murakami, and Yamashiro, but collectively they did not reach a final structure. Much later in 1958, the correct structure of α-mangostin was proposed by Yates and Stout through extensive degradative studies and synthetic work [9]. This investigation included the correct molecular weight determination using X-ray diffraction of tetrahydrodimethylmangostin, and the positions of the hydroxyl substituents in the basic xanthone skeleton were obtained by comparing the UV data of synthetic model compounds with those of α-mangostin and several derivatives. In turn, the presence and position of the two isopentenyl side chains were ascertained from cyclization, oxidation, and ozonolysis products that were investigated by IR and NMR spectroscopy [9]. Later, the structure of α-mangostin (1) was supported by mass spectrometric fragmentation and benzene-induced chemical shifts in the 1H NMR spectrum [10]. Furthermore, NOE measurements confirmed this structure together with additional mass spectrometric analysis [11]. Thereafter, over 85 secondary metabolites have been reported from G. mangostana so far, as shown in Figure 1. Of these, xanthone-type compounds (68 compounds, Table 1) have been found as the major secondary metabolites of this plant with the most abundant representatives being α-mangostin (1), β-mangostin (2), and γ-mangostin (3). Other constituents reported for G. mangostana are flavonoids (72–76) [37,38], triterpenoids (77–83) [37,39], benzophenones (69–71) [30,35,36], a biphenyl compound (84) [18], a pyrrole (85) [40], and a benzofuran (86) [41]. As may be seen from Table 1, not all of these compounds have been assigned trivial names.

Figure 1.

Structures of compounds isolated from G. mangostana

Table 1.

Xanthone Derivatives of Garcinia mangostana

| Trivial Name | Plant Parts | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-mangostin | fruits, stem, seed and aril | 9-15 |

| 2 | β-mangostin | fruits, stem | 15, 16 |

| 3 | γ-mangostin | fruits, stem | 17, 18 |

| 4 | fuscaxanthone C | stem | 18 |

| 5 | unnamed | fruits | 19 |

| 6 | unnamed | fruits | 20 |

| 7 | assiguxanthone-B trimethyl ether | heartwood | 21 |

| 8 | cowagarcinone B | heartwood, stem | 15, 21 |

| 9 | unnamed | fruits, heartwood | 20, 21 |

| 10 | unnamed | leaves | 22 |

| 11 | unnamed | leaves | 22 |

| 12 | garcinone D | fruits, stem | 12, 15, 23 |

| 13 | garcinone C | fruits | 12, 24 |

| 14 | mangostenone E | fruits | 12 |

| 15 | mangostenol | fruits | 25 |

| 16 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 17 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 18 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 19 | 6-deoxy-7-demethylmangostanin | fruits | 26 |

| 20 | mangostanin | fruits, heartwood | 21, 26 |

| 21 | 6-O-methylmangostanin | heartwood | 12, 21, 25 |

| 22 | mangostenone C | fruits | 12 |

| 23 | demethylcalabaxanthone | fruits, seed and aril | 12, 14, 19 |

| 24 | xanthone I | fruits, seed and aril, stem | 12, 14, 15, 27 |

| 25 | calabaxanthone | fruits | 19 |

| 26 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 27 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 28 | 8-deoxygartanin | fruits | 28 |

| 29 | garcinone A | fruits | 24 |

| 30 | gartanin | fruits | 28 |

| 31 | cudraxanthone G | fruits | 8 |

| 32 | 8-hydroxycudraxanthone G | fruits | 8 |

| 33 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 34 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 35 | unnamed | heartwood | 21 |

| 36 | mangostingone | fruits | 8 |

| 37 | 1-isomangostin | fruits | 19 |

| 38 | 11-hydroxy-1-isomangostin | fruits | 12 |

| 39 | mangostanol | fruits, stem | 12, 15, 29 |

| 40 | 3-isomangostin | fruits | 19 |

| 41 | mangostenone D | fruits | 12 |

| 42 | garcimangosone C | fruits | 30 |

| 43 | mangostinone | fruits | 12, 25, 31 |

| 44 | smeathxanthone A | fruits | 8 |

| 45 | unnamed | fruits | 26 |

| 46 | garcinone B | fruits | 12, 24, 25 |

| 47 | garcinone E | fruits | 12, 32 |

| 48 | tovophyllin A | fruits | 8 |

| 49 | thwaitesixanthone | fruits | 12 |

| 50 | garcimangosone B | fruits | 30 |

| 51 | garcimangosone A | fruits | 30 |

| 52 | mangostenone B | fruits | 25 |

| 53 | tovophyllin B | fruits | 25 |

| 54 | trapezifolixanthone | fruits | 25 |

| 55 | unnamed | fruits | 33 |

| 56 | unnamed | fruits | 33 |

| 57 | BR-xanthone B | fruits | 34 |

| 58 | mangostenone A | fruits | 25 |

| 59 | garciniafuran | heartwood | 21 |

| 60 | BR-xanthone A | fruits | 34 |

| 61 | unnamed | fruits | 19 |

| 62 | unnamed | fruits | 19 |

| 63 | dulxanthone D | heartwood | 35 |

| 64 | mangoxanthone | heartwood | 35 |

| 65 | mangosharin | stem | 15 |

| 66 | unnamed | heartwood | 35 |

| 67 | mangiferitin | heartwood | 36 |

| 68 | unnamed | heartwood | 35 |

USE OF MANGOSTEEN FRUIT JUICE AS A BOTANICAL DIETARY SUPPLEMENT

Mangosteen is being used extensively as a botanical dietary supplement in the United States, mainly in the form of a fruit juice. Standardized mangosteen products are based on the content of the xanthones present, principally α-mangostin (1). Most of these products marketed refer to various medicinal or health beneficial properties with reference to the available scientific literature. Thus far, there do not seem to have been any adverse clinical reports resulting from the use of mangosteen fruit juice products.

BIOLOGICAL STUDIES OF CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS

Purified mangosteen constituents have demonstrated a variety of biological activities related to common human diseases. In the following paragraphs, the effects of purified mangosteen xanthones as antioxidants, and on targets related primarily to infectious diseases, cancer, inflammation, and on the modulation of specific receptor-binding sites, will be discussed in turn.

ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY

Excess of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species has been found to be linked to various diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, diabetes mellitus, inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases [42]. In 1994, several antioxidant xanthone constituents of mangosteen extracts were identified as α-mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) together with epicatechin (62), and procyanidins A2 (63) and B2 (64), using a ferric thiocyanate method [38]. In the course of ongoing research on botanical dietary supplements conducted in the authors’ laboratory at The Ohio State University, bioactivity-guided fractionation of the pericarp of mangosteen, using a peroxynitrite-scavenging assay, led to five active xanthones [8-hydroxyxanthone (32), gartanin (30), α-mangostin (1), γ-mangostin (3), and smeathxanthone A (44)] with IC50 values < 10 μM, compared to a positive control substance, DL-penicillamine (IC50 7.4 μM) [8]. Elsewhere, at a single concentration, epicatechin (62), α-mangostin (1), and γ-mangostin (3) exhibited different antioxidant activities in DPPH, hydroxyl radical-scavenging, superoxide anion-scavenging, and ferric thiocyanate assays [43]. Additionally, 16 xanthones were tested in a hydroxyl radical-scavenging assay and it was found that γ-mangostin (3) was the most active (IC50 0.2 μg/mL) of the compounds tested and more potent than the positive control substance used, vitamin C (ascorbic acid) (IC50 0.4 μg/mL) [26]. It was also reported that α-mangostin (1) inhibited oxidative modification in a human low density lipoprotein Cu2+-induced oxidation system [44]. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that α-mangostin (1) exhibited a protective effect on lipid peroxidation and on an antioxidant tissue defense system against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats [45]. Accordingly, there is strong evidence from independent research in several different laboratories that supports the use of mangosteen fruit juice for its antioxidant effects.

INFECTIOUS DISEASE-RELATED TARGETS

Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

The incidences of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) infections have increased world-wide in human populations and have recently become a critical problem associated with high morbidity and mortality [46]. Iinuma and colleagues [47] examined 13 naturally occurring xanthones and two semi-synthetic xanthones from mangosteen for their inhibitory effects against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In this study, α-mangostin (1) showed anti-MRSA activity within the MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) range, 1.57–2.5 μg/mL, as compared to the positive control, vancomycin (3.13–6.25 μg/mL) [47]. Moreover, α-mangostin (1) in the presence of vancomycin exhibited incremental anti-MSRA activity that was not observed in the case of another test compound. α-Mangostin (1) was further investigated for its anti-vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) activity and synergistic effects with antibiotics [13]. It was observed that α-mangostin showed activity against five strains of VRE and three strains of VSE (vancomycin-sensitive Enterococci) with the MIC ranges, 3.13–6.25 μg/mL, and exerted anti-VRE activity synergistically with gentamicin.

Fifteen prenylated xanthones were evaluated for antituberculosis activity in an in vitro Mycobacterium tuberculosis assay and α-mangostin (1), β-mangostin (2) and garcinone B (46) exhibited inhibitory effects (MIC 6.25 μg/mL for all three compounds) [14]. α-Mangostin (1) has also demonstrated an inhibitory effect against Helicobacter pylori with a MIC value of 1.56 μg/mL [48].

Eight natural xanthones and nine derivatives of α-mangostin (1) were tested for antifungal activity against three fungi, Fusarium oxysporum vasinfectum, Alternaria tenuis, and Dreschlera oryzae. γ-Mangostin (3) exhibited the most potent antifungal activity against the three test organisms used in this study, when evaluated at 1000 ppm [49].

Anti-Malarial Activity

Malaria remains one of the most serious tropical infectious diseases for humans, and over 80% of cases in the world are caused mainly by Plasmodium falciparum [50]. α-Mangostin (1) and β-mangostin (2) were reported to be inhibitory (IC50 5.1 and ca. 7 μM, respectively) for the growth of P. falciparum clone D6 [50]. α-Mangostin (1) was evaluated further in FcM29-Cameroon (chloroquine resistant) and F32 (chloroquine sensitive) strains, and found to be active in the range 1.7–3.2 μg/mL [51]. Several modified derivatives were prepared based on the skeleton of α-mangostin (1). Of these compounds, xanthone derivatives with alkylamine groups exhibited the most potent inhibitory activity against P. falciparum in an in vitro assay [52].

HIV-1 Proteases and Reverse Transcriptase

HIV-1 is the etiological agent of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). The drugs used in current anti-HIV-1 combination chemotherapy, referred to as “highly active antiretroviral therapy” (HAART), inhibit both HIV-1 protease, responsible for the processing of viral structural proteins, and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, which copies the genomic RNA to integrate into the host’s DNA. These two enzymes are essential for viral replication [53]. Activity-guided fractionation of G. mangostana using a HIV-1 protease inhibition assay led to two active compounds, α-mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3), which demonstrated IC50 values of 5.1 and 4.8 μM, respectively, in a non-competitive manner [54]. In a recombinant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibition assay, of six isolates tested, β-mangostin (2) and epicatechin (62) showed weak inhibitory effects (42% and 48% at 200 μg/mL, respectively) [55].

GENERAL CANCER-RELATED TARGETS

Cytotoxicity for Cancer Cells

Cancer chemotherapeutic agents currently used therapeutically include a number of small-molecular drugs with potent cytotoxicity for cancer cells [56]. Cytotoxic natural products can thus afford useful libraries of novel compounds that may be utilized for further mechanistic study. Over 20 xanthones of mangosteen have been tested in in vitro cancer cell lines and the active compounds are summarized in Table 2 [12,57,58]. Of these cytotoxic xanthones, α-mangostin (1) was investigated against various molecular targets or signal transduction pathways. α-Mangostin (1) induced an apoptotic effect via the loss of membrane potential in HL-60 cells without altering the expression of bcl-2 family proteins and activation of MAP kinases [58,59]. Also, Ca2+-ATPase-dependent apoptosis in PC12 cells was demonstrated via mitochondrial pathways [60].

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity of mangosteen xanthonesa

| KB | BC-1 | NCI-H187 | HL-60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-mangostin (1) | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| β-mangostin (2) | 2.5 | 2 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| γ-mangostin (3) | 4.7 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| mangostenone C (22) | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.7 | - |

| mangostenone D (41) | >5 | 3.9 | >5 | - |

| demethylcalabaxanthone (23) | >5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | - |

| 24 | 3.7 | 3 | 2.2 | - |

| garcinone C (13) | >5 | 2.2 | 3.7 | - |

| garcinone D (12) | 3.6 | 2.8 | >5 | - |

| garcinone E (47)c | 2.7 | 1.4 | 3.7 | - |

| gartanin (30) | >5 | >5 | 1.1 | - |

| mangostanol (39) | >5 | >5 | 1.2 | - |

Results are expressed as ED50 values (μg/mL) and an ED50 value of <5 μg/mL is considered active.

Key to cell lines: BC-1 (human lymphoma); HL-60 (human leukemia); KB (human oral epidermoid carcinoma); NCI-H187 (human lung carcinoma).

This compound was evaluated in a total of 14 cancer cell lines [57].

In cell-cycle arrest assays, α-mangostin (1) and β-mangostin (3) exhibited G1 arrest while γ-mangostin (3) showed arrest at the S phase, associated with modulating the expression of cyclins, cdc2, and p27 in DLD-1 human colon cancer cells [61]. Furthermore, α-mangostin (1) increased levels of microRNA-143, which negatively regulates Erk5 at translation and augmented inhibitory activity when co-treated with 5-fluorouracil [62].

Sphingomyelinase

Sphingomyelinases are enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin (ceramide phosphorylcholine) into ceramides and phosphorylcholine and are involved in cell death, cell differentiation, and cell proliferation. Of these enzymes, acidic sphingomyelinase, a soluble glycoprotein, has been reported to be associated with a signal pathway via CD95 to induce apoptosis in some cells [63]. A recent study disclosed that α-mangostin (1) inhibited bovine brain-derived acidic sphingomyelinase (IC50 5.15 μM) in a selective manner when compared with neutral sphingomyelinase (IC50 46.5 μM) [64]. A small group of xanthone derivatives was synthesized to more fully understand the role of the prenyl group in the parent compound, α-mangostin (1), in mediating this type of activity [65].

Topoisomerases I and II

DNA topoisomerases resolve the topological problems associated with DNA replication, transcription, recombination, and chromatin remodeling by introducing temporary single- or double-strand breaks in the DNA. Of these enzymes, inhibition of topoisomerases I and II are known anticancer target molecules by irinotecan and topotecan (topoisomerase I), and etoposide and teniposide (topoisomerase II) [66]. Of the mangosteen xanthones, α-mangostin (1), β-mangostin (2), and γ-mangostin (3) were found to inhibit topoisomerases I and II, and, of three tested mangosteen xanthones, γ-mangostin (3) displayed the most potent inhibitory activity (IC50 5 μg/mL) against topoisomerase II when compared with etoposide (IC50 70 μg/mL) [66].

Cancer Chemoprevention

Cancer chemoprevention refers to intervention such as the prevention, delay or reversal of the process of carcinogenesis by ingestion of food, dietary supplements, or synthetic agents [67]. From plant sources including botanical dietary supplements, our group has investigated potential cancer chemopreventive agents that may block tumor initiation as a result of the induction of Phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes such as glutathione-S-transferase and quinone reductase. Other compounds may limit tumor progression and promotion from the inhibition of the aromatase enzyme [68]. As part of our ongoing laboratory work, xanthones with potential cancer chemopreventive activity have been found from mangosteen. Also, α-mangostin (1), the main xanthone of mangosteen, was evaluated in ex vivo and in vivo models relevant to cancer chemoprevention.

Aromatase Inhibition Activity

Aromatase is responsible for catalyzing the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgens and inhibition of the aromatase enzyme has been shown to reduce estrogen production throughout the body and to have a significant affect on the development and progression of hormone-responsive breast cancers [69,70]. Therefore, aromatase inhibitors may have potential use as either anticancer agents or for cancer chemoprevention. Of 12 xanthones tested from mangosteen fruits, four xanthones, γ-mangostin (3) (IC50 6.9 μM], garcinone D (12) (IC50 5.2 μM), α-mangostin (1) (IC50 20.7 μM) and garcinone E (47) (IC50 25.1 μM), were found to be active in a microsomal aromatase assay. Of these, in a follow-up cell-based assay using SK-BR-3 hormone-independent human breast cancer cells, γ-mangostin (3) was found to be more active in inhibiting aromatase in cells than letrozole used as a positive control [71].

Quinone Reductase Induction Activity

NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase (QR) is a phase II metabolizing enzyme and its induction is considered germane to cancer chemoprevention since this may lead to the more rapid detoxification of carcinogens [72,73]. Bioactivity-guided fractionation of the fruits of G. mangostana using a QR induction assay in Hepa 1c1c7 cells led to the isolation of four QR-inducing xanthones, 1,3,7-trihydroxy-2,8-di-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)xanthone (5), 2,3-dihydro-4,7-dihydroxy-2-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-6-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)furo[3,2-b]xanthen-5-one (6-deoxy-7-demethylmangostanin) (19), mangostanin (20), and 1,2-dihydro-1,8,10-trihydroxy-2-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-9-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)furo[3,2-a]xanthen-11-one (45), with CD (concentration required to double QR induction activity) values of 0.68, 2.2, 0.95, and 1.3 μg/mL, respectively. Eleven other xanthones of previously known structure were also evaluated in this assay system inclusive of α-mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3), but these were inactive [26].

Ex Vivo and In Vivo Studies Relevant to Cancer Chemoprevention

One of major mangosteen xanthones, α-mangostin (1), has been evaluated in regard to its cancer chemoprevention potential in both ex vivo and in vivo cancer chemoprevention models. In the first of these, α-mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) inhibited 7,12-dimethylbenz[α]anthracene-induced preneoplastic lesions in a mouse mammary organ culture system. Of these, α-mangostin (1) exhibited an IC50 value of 2.44 μM in this assay system [8]. When administered to rats in crude form, α-mangostin (1) prevented the induction and/or development of aberrant crypt foci, dysplastic foci, and accumulation of β-catenin on preneoplastic lesions induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH) in rat colon carcinogenesis [74].

INFLAMMATION-RELATED TARGETS

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is responsible for prostaglandin production and exists in two isoforms known as constitutive COX (COX-1) and inducible COX (COX-2). The transcriptional activation of COX-2 is regulated by nuclear factor κB through being mediated by inhibitor κB (IκB) kinase (IKK), which specifically catalyzes IκB phosphorylation and then leading to NF-κB nuclear translocation, which stimulates cis-acting κB element-mediated transcription [75]. γ-Mangostin (3) blocked prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) release and inhibited the expression of COX-2 in protein and mRNA levels when treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in C6 rat glioma cells [75,76]. Further mechanistic study demonstrated that direct inhibition of IKK activity by γ-mangostin (3) prevents COX-2 gene transcription at the NF-κB target gene, and thus this compound seems to be a new lead for anti-inflammatory drug development [55]. Another mangosteen xanthone, garcinone B (46), showed similar activity via the same mode of action as γ-mangostin (3) [77].

Inducible nitrogen oxide synthase (iNOS) is an important enzyme, along with COX, that mediates the inflammatory process. α-Mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) inhibited NO and PGE2 production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells through the inhibition of iNOS expression, rather than by iNOS enzymic activity itself or by interaction with COX-2 [78].

In an in vivo study using a carrageenan-induced paw edema model in mice, α-mangostin (1) (20 mg/kg) exhibited an inhibitory effect whereas γ-mangostin (3) did not significantly inhibit the paw edema [78].

MISCELLANEOUS EFFECTS OF MANGOSTEEN XANTHONES

α-Mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) were found to be inhibitors of the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (13 and 2 μM) and Ca2+-dependent protein kinase (21 and 5 μM) in wheat germ and rat liver [79]. Also, α-mangostin (1) exhibited an inhibitory effect on Ca2+-ATPase and Ca2+-transport of the rabbit skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (IC50 5 μM). α-Mangostin (1) inhibited Ca2+-ATPase in a non-competitive manner without affecting the ATP or Ca2+-binding site [80].

Mangostanol (39), α-mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) showed moderate inhibitory effects on cAMP phosphodiesterase (IC50 47, 24, and 50 μM, respectively), which plays an important role in the hydrolysis of the intracellular cAMP [81].

α-Mangostin (1) and γ-mangostin (3) shifted the concentration-contractile response curve in rabbit aortal assays for histamine and serotonin, which suggested that these two compounds selectively block, respectively, histaminergic and serotonergic receptors [82]. Furthermore, α-mangostin (1) inhibited histamine-induced contractions in the isolated rabbit thoracic aorta and guinea-pig trachea and the binding of [3H]mepyramine, a specific histamine H1 antagonist to rat aortal smooth muscle cells. This suggests that α-mangostin (1) is a competitive histamine H1 receptor antagonist [83].

Intracerebroventricular injection of γ-mangostin (3) inhibited a 5-fluoro-α-methyltryptamine (5-FMT)-induced head-twitch response in mice in the presence or absence of citalopram, a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)-uptake inhibitor. γ-Mangostin (3) did not affect locomotor activity mediated by 5-FMT via the activation of α1-adrenoceptors. Also, kinetic analysis of the [3H]-spiperone binding assay indicated that γ-mangostin (3) affected competitively the Kd value of spiperone. Therefore, γ-mangostin (3) is a promising 5-HT2A receptor antagonist in the central nervous system without blocking the release of 5-HT from the neuron [84].

OTHER BIOACTIVIE EFFECTS OF CRUDE EXTRACTS OF GARCINIA MANGOSTANA

A crude pericarp extract of G. mangostana exhibited inhibitory activity against α-amylase, for which inhibition is known to be effective in the treatment or prevention of non-insulin-dependent diabetes. The constituents responsible were proposed as proanthocyanidins by colorimetric analysis coupled with UV-visible and IR spectroscopy [7]. Also, a pericarp extract of G. mangostana was found to be useful as adjunct in treating oral malodors, but no active components were elucidated [85].

SYNTHESIS OF MANGOSTEEN XANTHONES

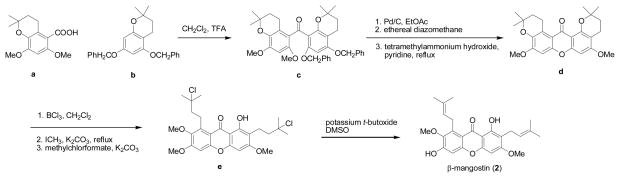

β-Mangostin (2) was the first natural mangosteen xanthone to be synthesized. Using 5,7-bisbenzyloxy-3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran (a) and 6,8-dimethoxy-3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-5-carboxylic acid (b) as starting materials, product c was formed by an acylation reaction and this was converted into product d in three steps, followed by a cleavage reaction with boron trichloride and selective methylation to yield product e. The final step was conducted in a solution of dimethylsulfoxide and potassium t-butoxide to furnish β-mangostin (2) [86]. No yield of this synthetic work was reported in the literature.

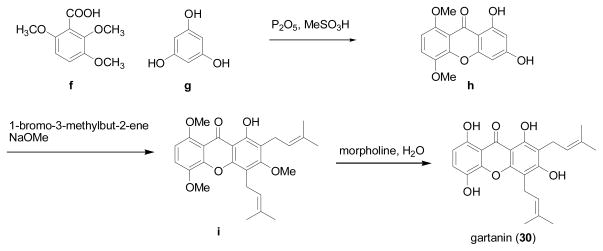

For the synthesis of gartanin (30), Bennett and colleagues designed a method (Scheme 2) that was published in 1990 [87]. Reaction of 2,3,6-trimethoxybenzoic acid (f) and phloroglucinol (g) was conducted in P2O5 and MeSO3H and yielded 1,3-dihydroxy-5,8-dimethoxyxanthone (h). Then, 3-methylbut-2-enylation of 1,3-dihydroxy-5,8-dimethoxyxanthone produced 1-hydroxy-3,5,8-trimethoxy-2,4-di-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-xanthone (i), which was demethylated in hot aqueous morpholine to give gartanin (30). Using a similar synthetic process, the mangosteen xanthone 10, 1,5,8-trihydroxy-3-methoxy-2-[3-methylbut-2-enyl]xanthone, was also synthesized [87]. No yield of this synthetic work was reported in the literature.

Scheme 2.

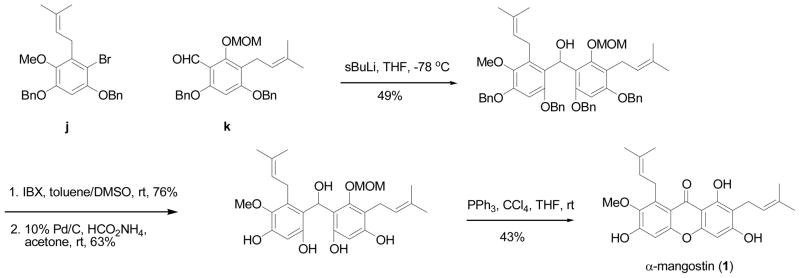

α-Mangostin (1) is recognized as one of the major active mangosteen secondary metabolites. The first direct synthesis of this xanthone was achieved by Iikubo et al. in 2002 [64]. This direct synthetic method started with the syntheses of two fragments (j and k). Fragment j was made through the introduction of a benzyl protecting group to 2,4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, followed by Baeyer-Villiger oxidation and acid hydrolysis, and further bromination, allylation, and Lemieux-Johnson oxidation. Another fragment k was prepared from 1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene, which was subjected to several steps (MOM protection, prenylation, TBS-protection, DIBAL-reduction, and IBX oxidation). A coupling process and a cyclization reaction using a PPh3-CCl4 protocol completed the total synthesis of 1.

CONCLUSIONS

As shown in this short review on the Garcinia mangostana (mangosteen) constituents isolated so far, chemically diverse xanthone analogs are the most characteristic secondary metabolites from this plant, and their activity has been evaluated against a wide variety of biological targets. Among these, studies have shown cytotoxicity of the mangosteen xanthone derivatives against several cancer cell lines, and it is of interest to note that gambogic acid, a prenylated xanthone from Garcinia hanburyi, a closely related species to G. mangostana, is now in phase I clinical trials as an anticancer agent in the People’s Republic of China [88]. Moreover, there is now very good evidence that α- and γ-mangostins are potent antioxidants in standard bioassays. The use of mangosteen juice as an antioxidant botanical dietary supplement containing substantial amounts of xanthones may be supported from the literature available thus far.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 3.

Acknowledgments

Experimental work conducted in the authors’ laboratory was supported by faculty start-up funding from the Molecular Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention Program of The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (to A. D. Kinghorn).

References

- 1.Farnsworth NR, Bunyapraphatsara N. Thai Medicinal Plants Recommended for Primary Health Care System. Medicinal Plant Information Center; Bangkok: 1992. pp. 160–162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moongkarndi P, Kosem N, Kaslungka S, Luanratana O, Pongpan N, Neungton N. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:161. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrity AR, Morton GA, Morton JC. Nutraceutical mangosteen composition. 6730333 B1 20040504. US Patent. 2004:7.

- 4.Nutrition Business Journal. NBJ’s Supplement Business Report 2007: an analysis of markets, trends, competition and strategy in the US dietary supplement industry. Penton Media Inc; San Diego: 2007. pp. 82–240. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weecharangsan W, Opanasopit P, Sukma M, Ngawhirunpat T, Sotanaphun U, Siripong P. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:281. doi: 10.1159/000092991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomnawang MT, Surassmo S, Nukoolkarn VS, Gritsanapan W. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:401. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loo AEK, Huang D. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9805–9810. doi: 10.1021/jf071500f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung H-A, Su B-N, Keller WJ, Mehta RG, Kinghorn AD. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2077. doi: 10.1021/jf052649z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yates P, Stout GH. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:1691. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stout GH, Krahn MM. Chem Commun. 1968:211. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan ASC. Planta Med. 1973;24:297. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suksamrarn S, Komutiban O, Ratananukul P, Chimnoi N, Lartpornmatulee N, Suksamrarn A. Chem Pharm Bull. 2006;54:301. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakagami Y, Iinuma M, Piyasena KGNP, Dharmaratne HRW. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:203. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suksamrarn S, Suwannapoch N, Phakhodee W, Thanuhiranlert J, Ratananukul P, Chimnoi N, Suksamrarn A. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51:857. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ee GCL, Daud S, Taufiq-Yap YH, Ismail NH, Rahmani M. Nat Prod Res. 2006;20:1067. doi: 10.1080/14786410500463114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yates P, Bhat HB. Can J Chem. 1968;46:3770. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jefferson A, Quillinan AJ, Scheinmann F, Sim KY. Aust J Chem. 1970;23:2539. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dharmaratne HRW, Piyasena KGNP, Tennakoon SB. Nat Prod Res. 2005;19:239. doi: 10.1080/14786410410001710582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahabusarakam W, Wiriyachitra P, Taylor WC. J Nat Prod. 1987;50:474. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen AK, Sarkar KK, Majumder PC, Banerji N. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:183. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilar, Harrison LJ. Phytochemistry. 2002;60:541. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parveen M, Uddin Khan N. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:3694. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen AK, Sarkar KK, Majumder PC, Banerji N. Indian J Chem. 1986;25B:1157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen AK, Sarkar KK, Mazumder PC, Banerji N, Uusuori R, Hase TA. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:1747. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suksamrarn S, Suwannapoch N, Ratananukul P, Aroonlerk N, Suksamrarn A. JNat Prod. 2002;65:761. doi: 10.1021/np010566g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chin Y-W, Jung H-A, Chai H, Keller WJ, Kinghorn AD. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:754–758. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sen AK, Sarkar KK, Mazumder PC, Banerji N, Uusvuori R, Hase TA. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:2223. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Govindachari TR, Kalyanaraman PS, Muthukumaraswamy N, Pai BR. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:3919. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chairungsrilerd N, Takeuchi K, Ohizumi Y, Nozoe S, Ohta T. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:1099. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y-L, Chen C-C, Chen Y-J, Huang R-L, Shieh B-J. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:903. doi: 10.1021/np000583q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asai F, Tosa H, Tanaka T, Iinuma M. Phytochemistry. 1995;39:943. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta PK, Sen AK, Sarkar KK, Banerji N. Indian J Chem. 1987;26B:281. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopalakrishnan G, Balaganesan B. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:607. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balasubramanian K, Rajagopalan K. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:1552. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilar, Nguyen L-HD, Venkatraman G, Sim K-Y, Harrison LJ. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1718. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holloway DM, Scheinmann F. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:2517. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parveen M, Khan NUD, Achari B, Dutta PK. Fitoterapia. 1990;61:86. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshikawa M, Harada E, Miki A, Tsukamoto K, Liang SQ, Yamahara J, Murakami N. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1994;114:129. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.114.3_176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parveen M, Khan NUD, Achari B, Dutta PK. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:361. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krajewski D, Toth G, Schreier P. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:141. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakai S, Katsura M, Takayama H, Aimi N, Chokethaworn N, Suttajit M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1993;41:958. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu L, Zhao M, Yang B, Zhao Q, Jiang Y. Food Chem. 2007;104:176. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams P, Ongsakul M, Proudfoot J, Croft K, Beilin L. Free Radic Res. 1995;23:175. doi: 10.3109/10715769509064030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sampath PD, Vijayaraghavan K. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2007;21:336. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:893. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iinuma M, Tosa H, Tanaka T, Asai F, Kobayashi Y, Shimano R, Miyauchi K-I. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1996;48:861. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb03988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasegawa H, Sakai S, Aimi N, Takayama H, Koyano T. 08231396. Jpn Kokai Tokkyo Koho, JP. 1996:5.

- 49.Gopalakrishnan G, Banumathi B, Suresh G. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:519. doi: 10.1021/np970165u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riscoe M, Kelly JX, Winter R. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2539. doi: 10.2174/092986705774370709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azebaze AGB, Meyer M, Valentin A, Nguemfo EL, Fomum ZT, Nkengfack AE. Chem Pharm Bull. 2006;54:111. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahabusarakam W, Kuaha K, Wilairat P, Taylor W. Planta Med. 2006;72:912. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muhanji CI, Hunter R. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1207. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen S-X, Wan M, Loh B-N. Planta Med. 1996;62:381. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu J, Chen J, Zhao Y, Wang R, Zheng Y, Zhou J. Yunnan Zhiwu Yanjiu. 2006;28:319. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Newman DJ, Gragg GM. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ho C-K, Huang Y-L, Chen C-C. Planta Med. 2002;68:975. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Kobayashi E, Ohguchi K, Ito T, Tanaka T, Iinuma M, Nozawa Y. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:1124. doi: 10.1021/np020546u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Yi H, Ohguchi K, Ito T, Tanaka T, Kobayashi E, Iinuma M, Nozawa Y. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:5799. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sato A, Fujiwara H, Oku H, Ishiguro K, Ohizumi Y. J Pharm Sci. 2004;95:33. doi: 10.1254/jphs.95.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Ohguchi K, Ito T, Tanaka T, Iinuma M, Nozawa Y. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:6064. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagawa Y, Iinuma M, Naoe T, Nozawa Y, Akao Y. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:5620. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goñi FM, Alonso A. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iikubo K, Ishikawa Y, Ando N, Umezawa K, Nishiyama S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:291. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hamada M, Iikubo K, Ishikawa Y, Ikeda A, Umezawa K, Nishiyama S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3151. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tosa H, Iinuma M, Tanaka T, Nozaki H, Ikeda S, Tsutsui K, Tsutsui K, Yamada M, Fujimori S. Chem Pharm Bull. 1997;45:418. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sporn MB, Dunlop NM, Newton DL, Smith JM. Fed Proc. 1976;35:1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kinghorn AD, Su B-N, Jang DS, Chang L-C, Lee D, Gu JQ, Carcache-Blanco EJ, Pawlus AD, Lee SK, Park EJ, Cuendet M, Gills JJ, Bhat K, Park HS, Mata-Greenwood E, Song LL, Jang M, Pezzuto JM. Planta Med. 2004;70:691. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Siiteri PK. Cancer Res. 1982;42(Suppl 8):3269s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelloff GJ, Lubet RA, Lieberman R, Eisenhauer K, Steele VE, Crowell JA, Hawk ET, Boone CW, Sigman CC. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 1998;7:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.BalunasMJSu B, Brueggemeier RW, Kinghorn AD. J Nat Prod. 2008 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gerhauser C, You M, Liu J, Moriarty RM, Hawthorne M, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Cancer Res. 1997;57:272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su B-N, Gu J-Q, Kang Y-H, Park E-J, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Mini-Rev Org Chem. 2004;1:115. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nabandith V, Suzui M, Takamitsu M, Tatsuya K, Kinjo T, Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Iinuma M, Yoshimi N. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2004;5:433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakatani K, Nakahata N, Arakawa T, Yasuda H, Ohizumi Y. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:73. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakatani K, Yamakuni T, Kondo N, Arakawa T, Oosawa K, Shimura S, Inoue H, Ohizumi Y. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:667. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamakuni T, Aoki K, Nakatani K, Kondo N, Oku H, Ishiguro K, Ohizumi Y. Neurosci Lett. 2006;394:206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen L-G, Yang L-L, Wang C-C. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:688. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jinsart W, Ternai B, Buddhasukh D, Polya GM. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3711. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)97514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Furukawa K, Shibusawa K, Chairungsrilerd N, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1996;71:337. doi: 10.1254/jjp.71.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chairungsrilerd N, Takeuchi K, Ohizumi Y, Nozoe S, Ohta T. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:1099. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa K-I, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. Planta Med. 1996;62:471. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa K-I, Ohta T, Nozoe S, Ohizumi Y. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314:351. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chairungsrilerd N, Furukawa K-I, Tadano T, Kisara K, Ohizumi Y. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:855. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rassameemasmaung S, Sirikulsathean A, Amornchat C, Hirunrat K, Rojanapanthu P, Gritsanapan WJ. Int Acad Periodontol. 2007;9:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee H-H. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1981;1:3205. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bennett G, Lee H-H, Lee L-P. J Nat Prod. 1990;53:1463. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhou ZT, Wang JW. Chin J New Drugs. 2007;16:79. [Google Scholar]