Abstract

Objectives

To synthesize methodologically comparable evidence from the published literature regarding the outcomes of tiered formularies and therapeutic reference pricing of prescription drugs.

Methods

We searched the following electronic databases: ABI/Inform, CINAHL, Clinical Evidence, Digital Dissertations & Theses, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews (which incorporates ACP Journal Club, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Methodology Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Health Technology Assessments and NHS Economic Evaluation Database), EconLit, EMBASE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, MEDLINE, PAIS International and PAIS Archive, and the Web of Science. We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and several grey literature sources. We sought English-language studies published from 1986 to 2007 that examined the effects of either therapeutic reference pricing or tiered formularies, reported on outcomes relevant to patient care and cost-effectiveness, and employed quantitative study designs that included concurrent or historical comparison groups. We abstracted and assessed potentially appropriate articles using a modified version of the data abstraction form developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group.

Results

From an initial list of 2964 citations, 12 citations (representing 11 studies) were deemed eligible for inclusion in our review: 3 studies (reported in 4 articles) of reference pricing and 8 studies of tiered formularies. The introduction of reference pricing was associated with reduced plan spending, switching to preferred medicines, reduced overall drug utilization and short-term increases in the use of physician services. Reference pricing was not associated with adverse health impacts. The introduction of tiered formularies was associated with reduced plan expenditures, greater patient costs and increased rates of non-compliance with prescribed drug therapy. From the data available, we were unable to examine the hypothesis that tiered formulary policies result in greater use of physician services and potentially worse health outcomes.

Conclusion

The available evidence does not clearly differentiate between reference pricing and tiered formularies in terms of policy outcomes. Reference pricing appears to have a slight evidentiary advantage, given that patients’ health outcomes under tiered formularies have not been well studied and that tiered formularies are associated with increased rates of medicine discontinuation.

Most community-based spending on prescription drugs in Canada is financed through provincial (40%) and private (35%) drug plans.1 From 1997 to 2007, spending under provincial drug plans grew from $3.1 billion to $9.2 billion, and spending under private plans grew from $2.8 billion to $7.8 billion. Under such financial pressures, it is possible that reference pricing and tiered formularies will be adopted more and more by public and private insurers in Canada. Because these coverage policies are similar in intent but slightly different in structure, we sought to review and compare evidence concerning their effects. Although the authors of several reviews and commentaries have looked at tiered formularies and reference pricing policies,2-5 none thus far has conducted a systematic comparison of evidence regarding these 2 formulary interventions.

Under reference pricing policies, a drug plan generally covers low-cost options within specified drug categories and requires patients to pay any price differences if higher-cost products are prescribed. Categories may include only chemically equivalent drugs (generic reference pricing), or they may include chemically distinct products with comparable therapeutic effects (therapeutic reference pricing). Public and private insurers in Canada and abroad use generic reference pricing extensively. The province of British Columbia and several countries outside Canada have applied therapeutic reference pricing.6,7

Under a tiered formulary, patients generally face incrementally higher copayments for different treatment options: a relatively low copayment applies to “preferred” drugs within a class (e.g., $5 for generics), a higher copayment to second-tier products within a class (e.g., $10 for “preferred brands” for which the insurer has negotiated a rebate) and an even higher copayment to other drugs on the formulary (e.g., $25 for other brands within a drug class). Tiered formularies are used most extensively in the United States. As of 2007, 91% of US workers with employer-sponsored drug coverage faced at least 2 cost-sharing tiers for prescription drugs, and 75% faced at least 3 tiers.8

As reference pricing and tiered formularies are already commonly used to decrease drug plan expenditures, it is important to understand their implications for drug costs, use of medicines and patients’ health outcomes. Our objective in this study was to synthesize and contrast methodologically comparable evidence from the published literature regarding the outcomes of both reference pricing and tiered formulary policies.

Methods

Searching

We searched for English-language studies published from 1986 to 2007 that examined drug plan enrollees affected by the introduction of either therapeutic reference pricing or tiered formularies, reported on outcomes relevant to patient care and cost effectiveness, and employed quantitative study designs that included concurrent or historical comparison groups. The starting date for the search was chosen to predate what were believed to be the first introductions of reference pricing policies, in 1989. Because those formulary interventions came into use in the late 1980s, a 20-year window beginning shortly beforehand was thought to be sufficient to capture the relevant literature.

We searched the following electronic databases: ABI/Inform, CINAHL, Clinical Evidence, Digital Dissertations & Theses, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews (which incorporates ACP Journal Club, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Methodology Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Health Technology Assessments and NHS Economic Evaluation Database), EconLit, EMBASE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, MEDLINE, PAIS International and PAIS Archive, and the Web of Science. We also performed web-based and open repository searches for grey literature, traced citations to and from relevant articles, hand-searched core journals from which several citations had been found electronically and searched our personal libraries for additional articles. We searched databases using subject headings and key words clustered around the concepts of prescription drugs, the interventions of interest (using various synonyms for copayments, tiers, and reference pricing) and, where possible, study methodologies; see Appendix 1 for search details.

Study selection

Articles were screened without blinding, through a sequence of title (by DG), abstract (by DG and SM), and full-text review and data abstraction (by SM and GH, plus EK and JL to reconcile discrepancies). As an aid in selecting the studies, we used a modified version of the data abstraction form developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group.9 We chose our inclusion criteria to select quantitative studies that analyzed the impact of tiered formularies or reference pricing using patient-level data in an acceptable research design. The following designs were deemed acceptable: randomized controlled policy trials; before-and-after, or pre/post, studies with nonrandomized comparison groups; interrupted time series analyses with or without comparison groups, and pre/post studies without a comparison group. We excluded analyses that were based on post-only or cross-sectional designs, analyses that used aggregated drug utilization and/or cost data, and analyses pertaining to policies in developing countries. We did not perform inter-rater reliability assessments but relied on a third reviewer to resolve discrepancies.

Data abstraction

Full-text reviewers (SM and GH) independently abstracted data from the studies. They first abstracted the setting in which the study had been conducted, including the study population and geographic setting. They then described the intervention of interest, including an indication of whether the intervention involved introduction of a tiered formulary or reference pricing, the date of introduction and the policy prior to the introduction. The reviewers then outlined the specific outcomes that each study examined (e.g., drug use for acute conditions, drug expenditures, physician visits), as well as the study design, the analytic methods and the total observation period for the study. Finally, the reviewers independently abstracted the key findings from each article for each outcome of interest. These abstractions were then entered into a table, examined and translated into narrative abstracts.

Results

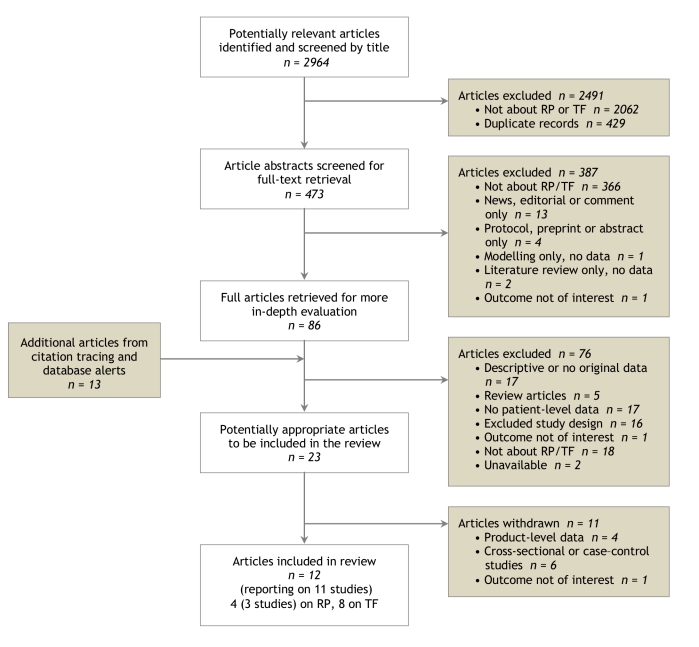

We identified a total of 2964 potentially relevant citations (Figure 1). By reviewing the citation titles, we eliminated 2491 citations (primarily drug-specific clinical studies). Review of the remaining abstracts eliminated all but 86 articles. An additional 13 articles were identified through citation tracing, of which 1 article was found to be unavailable because it was under peer review. After full-text screening, 12 articles representing 11 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in our review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection

Four of the included papers, representing 3 studies, assessed the impact of reference pricing. All of these studies examined the implementation of reference pricing during the mid-1990s under BC’s PharmaCare program for senior citizens.10-13 The other 8 studies assessed the impact of changes in tiered formularies. Seven of these looked at the effect of changes in tiered formularies for non-elderly enrollees of employment-related private insurance in the United States.14-20 The eighth study assessed the impact of changes in tiered formularies on child dependents of enrollees of employment-related private insurance plans in the United States.21

Impacts of reference pricing policies

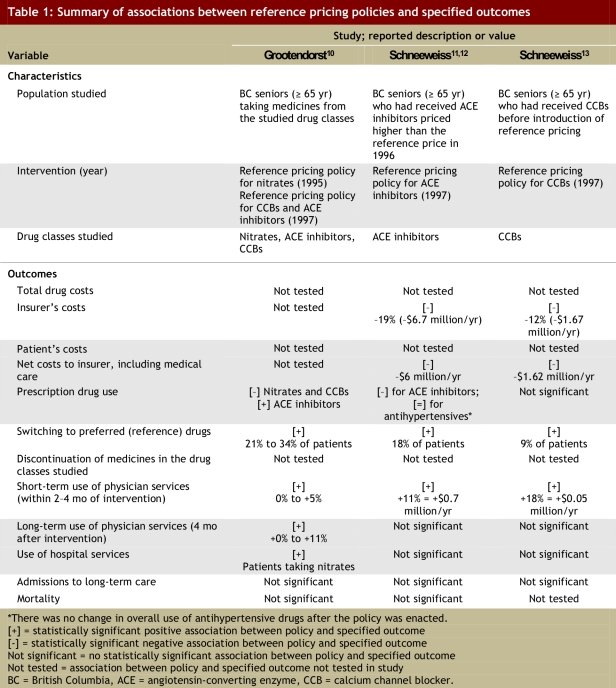

The associations reported in the 3 studies of reference pricing included in this review are summarized in Table 1. These studies assessed the impact of reference pricing for a total of 3 categories of drug treatment: nitrate drugs, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers (CCBs). Schneeweiss and colleagues11-13 and Grootendorst and colleagues10 found that between 9% and 34% of patients switched to fully covered (reference) products after reference pricing was implemented. Grootendorst and colleagues10 found that overall use of CCBs declined upon implementation of reference pricing, whereas Schneeweiss and colleagues13 found that the reduction in overall use of CCBs was not statistically significant after adjustment for pre-policy trends. The reverse was true for these authors’ findings with respect to the use of ACE inhibitors.10,12

Table 1.

Summary of associations between reference pricing policies and specified outcomes

Schneeweiss and colleagues12,13 found that the changes in utilization associated with reference pricing resulted in savings to insurers that ranged from 12% to 19% ($1.67 million to $6.7 million per year) of spending on related medicines. Both sets of researchers found that reference pricing in British Columbia was associated with an increase in physician services during the first 2 to 4 months after the policy change, which partially offset the savings in drug costs to the insurer.10-13 The researchers observed different patterns with respect to longer-term use of physician services: Schneeweiss and colleagues11-13 found no such association, whereas Grootendorst and colleagues10 found evidence of increased use of physician services beyond 4 months for 2 of the 3 categories studied (CCBs and ACE inhibitors). Schneeweiss and colleagues12,13 estimated that the annual net savings after accounting for expenses related to medical care were between $1.62 million and $6 million.

For 2 of the 3 drug categories investigated (CCBs and ACE inhibitors), Schneeweiss and colleagues11,13 and Grootendorst and colleagues10 found that reference pricing was not associated with any change in the use of hospital services. In the single study investigating the impact of reference pricing for nitrate drugs, Grootendorst and colleagues found that reference pricing was associated with increased long-term probability of bypass or revascularization.10

Impacts of tiered formularies

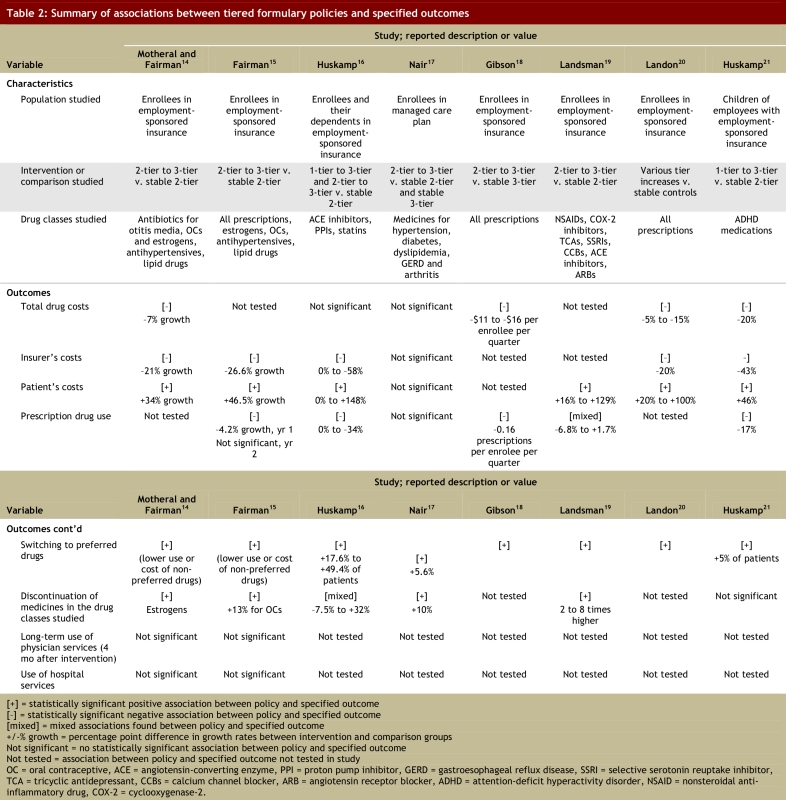

The associations observed in the studies of tiered formularies included in this review are summarized in Table 2. Despite differences in the populations and drug categories examined, these studies yielded a number of consistent findings. Most studies assessing such associations found that adding tiers to copayments for prescription drugs in the US private insurance market was associated with a reduction in total spending (decreases of 5%–20%).16,18,20,21 Nair and colleagues15 did not find statistically significant associations between adding tiers to formularies and changes in total spending. Where such associations were observed, reductions in total spending were the result of 3 common findings across the studies and across the drug classes investigated. Adding tiers to copayment structures was associated with increased switching within drug classes in all 8 included studies (switching toward “preferred” drugs on formulary occurring among 5% to 49.4% of patients),14-21 decreased overall utilization of affected medicines,15,16,18,19,21 and either no change21 or an increase in the rate of discontinuation of prescribed drug treatments.14-17,19

Table 2.

Summary of associations between tiered formulary policies and specified outcomes

In most of the studies that investigated the distribution of costs, employing tiered formularies was associated with lower spending by the drug plan14-16,20,21 and greater spending by patients.14-16,19-21 In the study by Nair and colleagues,17 changes in spending by the plan and by patients were consistent with the findings of other studies but were not statistically significant.

None of the studies of tiered formularies included in our review assessed the potential health outcomes resulting from the policy. However, 2 studies showed that moving from a 2-tier formulary to a 3-tier formulary was not associated with increased use of medical or hospital services.14,15

The single study of the effects of tiered formularies on the use of medicines by children was the only study not to find an association between the policy and medicine discontinuation.21 In the single study that assessed differences in effects on treatments for acute and chronic conditions, there were greater relative reductions in the utilization of and persistence with treatments for acute conditions.19

Discussion

The rapid rise in the use of tiered formularies by private insurance plans in the United States may be a harbinger of future trends in Canada: given rising medicine costs, it is likely that incentive structures for cost-sharing with patients will be adopted more widely here in the future. Policy-makers and health care managers will therefore require as much evidence as possible regarding such incentives. In this study, we have weighed the evidence regarding 2 comparable policy options: tiered formularies and reference pricing.

Despite over a decade of experience with the implementation of these policy interventions, and despite extensive searching of the literature on our part, we found few studies of the impacts of reference pricing and tiered formularies that met our relatively strict inclusion criteria. The most common finding was that patients facing either reference pricing or tiered formularies often switched to medications with preferred coverage. Studies of reference pricing suggest that this approach is also associated with short-term increases in the use of physician services, which may be interpreted as a transaction cost associated with switching medications. The balance of the evidence concerning health services use, hospital admissions and deaths indicates that reference pricing has not been associated with adverse health impacts. Surprisingly, only 2 of the 8 studies of tiered formularies included in this review assessed such outcomes or surrogates thereof.14,15 This gap in knowledge is potentially critical, given that tiered formularies were associated with reduced use of medicines, increased medicine discontinuation or both in 7 of the 8 studies of this policy approach.14-19,21 More research is required to examine the hypothesis that tiered formulary policies may result in increased use of physician services and potentially worse health outcomes.

The evidence that we examined in this systematic review suggests that the patient incentives created by reference pricing policies and tiered formularies work, insofar as they alter prescription drug use and save on drug costs. However, the gaps in evidence are sources of some concern. We conclude that reference pricing has a slight evidentiary advantage, given that patients’ health outcomes under tiered formularies have not been adequately studied and given that tiered formularies were associated with increased rates of medicine discontinuation.

Because of our stringent inclusion criteria regarding study design and outcomes, the final number of studies included in this systematic review was small. Moreover, the literature we found pertaining to reference pricing and tiered copayments described 2 distinct contexts: public insurance in a Canadian province and private insurance in the United States. Our focus on studies published in English is a potential limitation in this regard, given that there may be non-English literature concerning reference pricing and tiered formularies in other settings, such as Germany. The English literature on experiences outside of North America did not meet our inclusion criteria.

When policy options for Canada are considered, information costs and transaction costs for both prescribers and patients should be taken into account along with the evidence presented here. With dozens of potential formularies to consider for their patient rosters, US physicians may not have the time or resources necessary to determine for each patient which drugs are on which tier. Drugs with high copayments may be prescribed unintentionally under such circumstances, potentially increasing patients’ costs, straining physician–patient relationships, reducing adherence to treatments and worsening health outcomes. These problems may explain the association between tiered copayments and medicine discontinuation in the United States. Such adverse policy outcomes might be minimized if cost-sharing with patients, through reference pricing or tiered formularies, were to be harmonized across all payers within a jurisdiction (e.g., within each province).

Synthesizing the evidence for the purposes of this systematic review revealed an important gap in the existing research: specifically, the impacts of tiered formulary policies on patients’ health have not been adequately studied. This gap is particularly significant given that tiered formularies are associated with increased rates of medicine discontinuation. Further research regarding the impact of tiered formularies on patients’ health outcomes is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elizabeth Kinney and Jonathan Lam for assistance with this review.

Biographies

Steve Morgan, PhD, is associate professor and associate director of the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research (CHSPR) in the School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Gillian Hanley, MA, is a research assistant with the Program in Pharmaceutical Policy at CHSPR and a doctoral student of the School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia.

Devon Greyson, MLIS, is the information specialist for the Program in Pharmaceutical Policy at CHSPR, University of British Columbia.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Search strategy: Sources, search strategy and terms, and inclusion criteria

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Steve Morgan is supported in part by a New Investigator award from the CIHR and a Scholar award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). Gillian Hanley is supported by graduate training awards from the CIHR and MSFHR. The views presented here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of the CIHR or the MSFHR.

Contributors: Steve Morgan was responsible for project conception and acquisition of funding, reviewing article titles, abstracts and full text for possible inclusion in the study, abstracting information from included articles, and producing the first draft of the research article. Gillian Hanley was responsible for reviewing full text of articles for possible inclusion in the study, abstracting information from included articles, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. Devon Greyson was responsible for designing and implementing the search strategy, reviewing article titles, abstracts and full text for possible inclusion in the study, and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Drug expenditure in Canada 1985–2007. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2008. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/Drug_Expenditure_in_Canada_1985_2007_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aaserud M, Dahlgren AT, Kösters JP, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, Sturm H. Pharmaceutical policies: effects of reference pricing, other pricing, and purchasing policies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Apr 19;(2):CD005979. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puig-Junoy Jaume. What is required to evaluate the impact of pharmaceutical reference pricing? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2005;4(2):87–98. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200504020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman Dana P, Joyce Geoffrey F, Zheng Yuhui. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298(1):61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17609491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewa CS, Hoch JS. Fixed and flexible formularies as cost-control mechanisms. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2003;3(3):303–315. doi: 10.1586/14737167.3.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneeweiss Sebastian. Reference drug programs: effectiveness and policy implications. Health Policy. 2006 Jun 13;81(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanavos Panos, Reinhardt Uwe. Reference pricing for drugs: is it compatible with U.S. health care? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(3):16–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.16. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12757268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claxton G, Gabel J, DiJulio B, Whitmore H, Pickreign J, Finder B, Jacobs P, Hawkins S. Employer health benefits — 2007 annual survey. Chicago: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist. Ottawa: Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group; 2002. http://www.epoc.cochrane.org/Files/Website%20files/Documents/Reviewer%20Resources/datacollectionchecklist.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grootendorst PV, Dolovich LR, Holbrook AM, Levy AR, O-Brien BJ. The impact of reference pricing of cardiovascular drugs on health care costs and health outcomes: evidence from British Columbia. Volume 2: Technical report. Hamilton: MacMaster University; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneeweiss Sebastian, Walker Alexander M, Glynn Robert J, Maclure Malcolm, Dormuth Colin, Soumerai Stephen B. Outcomes of reference pricing for angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):822–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003087. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=11893794&promo=ONFLNS19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneeweiss Sebastian, Soumerai Stephen B, Glynn Robert J, Maclure Malcolm, Dormuth Colin, Walker Alexander M. Impact of reference-based pricing for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on drug utilization. CMAJ. 2002;166(6):737–745. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11944760. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneeweiss Sebastian, Soumerai Stephen B, Maclure Malcolm, Dormuth Colin, Walker Alexander M, Glynn Robert J. Clinical and economic consequences of reference pricing for dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(4):388–400. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motheral B, Fairman KA. Effect of a three-tier prescription copay on pharmaceutical and other medical utilization. Med Care. 2001;39(12):1293–1304. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairman Kathleen A, Motheral Brenda R, Henderson Rochelle R. Retrospective, long-term follow-up study of the effect of a three-tier prescription drug copayment system on pharmaceutical and other medical utilization and costs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(12):3147–3161. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huskamp Haiden A, Deverka Patricia A, Epstein Arnold M, Epstein Robert S, McGuigan Kimberly A, Frank Richard G. The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2224–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa030954. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=14657430&promo=ONFLNS19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair Kavita V, Wolfe Pamela, Valuck Robert J, McCollum Marianne M, Ganther Julie M, Lewis Sonja J. Effects of a 3-tier pharmacy benefit design on the prescription purchasing behavior of individuals with chronic disease. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(2):123–133. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.2.123. http://www.amcp.org/data/jmcp/Research-123-133.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson Teresa B, McLaughlin Catherine G, Smith Dean G. A copayment increase for prescription drugs: the long-term and short-term effects on use and expenditures. Inquiry. 2005;42(3):293–310. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_42.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landsman Pamela B, Yu Winnie, Liu XiaoFeng, Teutsch Steven M, Berger Marc L. Impact of 3-tier pharmacy benefit design and increased consumer cost-sharing on drug utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(10):621–628. http://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=2957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landon Bruce E, Rosenthal Meredith B, Normand Sharon-Lise T, Spettell Claire, Lessler Adam, Underwood Howard R, Newhouse Joseph P. Incentive formularies and changes in prescription drug spending. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(6 Pt 2):360–369. http://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=3330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huskamp Haiden A, Deverka Patricia A, Epstein Arnold M, Epstein Robert S, McGuigan Kimberly A, Muriel Anna C, Frank Richard G. Impact of 3-tier formularies on drug treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):435–441. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.435. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15809411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]