Abstract

Background

Lifestyle behaviours have significant health and economic consequences. Primary care providers play an important role in promoting healthy behaviours. We compared the performance of primary care models in delivering health promotion and identified practice factors associated with its delivery.

Methods

Surveys were conducted in 137 randomly selected primary care practices in 4 primary care models in Ontario, Canada: 35 community health centres, 35 fee-for-service practices, 35 family health networks and 32 health service organizations. A total of 4861 adult patients who were visiting their family practice participated in the study. Qualitative nested case studies were also conducted at 2 practices per model. A 7-item question was used to evaluate health promotion. The main outcome was whether at least 1 of the 7 health promotion items was discussed at the survey visit. Multilevel logistic regressions were used to compare the models and determine performance-related practice factors.

Results

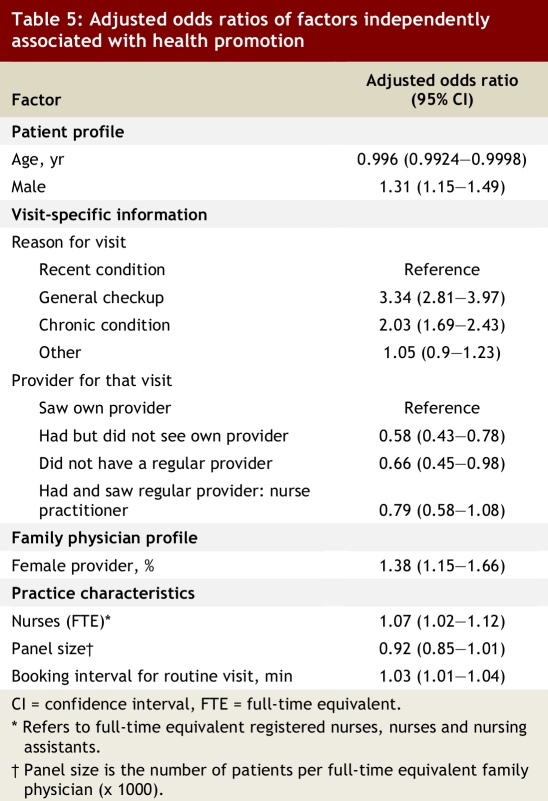

The rate of health promotion was significantly higher in community health centres than in the other models (the unadjusted difference ranged between 8% and 13%). This finding persisted after controlling for patient and family physician profiles. Factors independently positively associated with health promotion were as follows: reason for visit (for a general checkup: adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 3.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.81–3.97; for care for a chronic disease: AOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.69–2.43), patients having and seeing their own provider (for those not: AOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43–0.78), number of nurses in the practice (AOR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12), percentage of female family physicians (AOR 1.38, 95% CI 1.15–1.66), smaller physician panel size (AOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–1.01) and longer booking interval (AOR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.04). Providers in interdisciplinary practices viewed health promotion as an integral part of primary care, whereas other providers emphasized the role of relational continuity in effective health promotion.

Conclusion

We have identified several attributes associated with health promotion delivery. These results may assist practice managers and policy-makers in modifying practice attributes to improve health promotion in primary care.

Cigarette smoking, excessive use of alcohol, poor diet and lack of physical activity contribute to most of the leading causes of death and disability in Canada.1 Among Canadians 12 years of age and older, 23% smoke and 21% have alcohol-drinking patterns that can be described as risky.1Only 39% adhere to the recommendations concerning fruit and vegetable consumption and half lead a sedentary lifestyle; 59% of Canadian adults are obese or overweight.2 The economic burden of lifestyle-related health disorders is substantial. In 2002, $2.3 billion was spent in Canada on health care provision for alcohol-related problems alone.3 Nine percent of total health spending in the United States in 1998 was attributable to overweight and obesity.4

Health promotion is commonly defined as “the process of enabling individuals to take control over their health.”5 Improving the quality of health promotion and disease prevention has become a major focus of health care reform efforts internationally6-9 and is viewed as an important part of primary care.10 Clinical practice guidelines produced by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care recommend that primary care providers discuss healthy habits with their patients.11,12 However, a 1996 study reported that family physicians in Ontario, Canada, were dissatisfied with the extent to which they adhered to recommended guidelines for preventive care,13 and a related study performed on a subset of the same family physicians found significant deficits in the health promotion activities delivered to their patients.14

It is important that practice and organizational structures support the policy objectives of enhancing health promotion in primary care practices. In this article we compare the performance of primary care models of service delivery in Ontario in providing health promotion activities and determine what practice factors are associated with the delivery of health promotion. We evaluated 7 health promotion items derived from the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care: healthy food, home safety, family conflict, exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption and fall prevention (for patients 65 years of age or older). The evaluation was designed to be congruent with a broad conceptual framework for primary care organizations15 and forms part of a larger study funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Primary Health Care Transition Fund.

Methods

Design

This study is a component of a larger project, the Comparison of Models of Primary Care in Ontario (COMP-PC), which was approved by the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board. The COMP-PC has a mixed-methods design in which several performance parameters were evaluated. Data collection took place between October 2005 and June 2006. Full details of the COMP-PC methodology can be found in a separate publication.16 Here we focus on the patient self-reported measure of health promotion. The specific methodology used for this part of the study, which involved quantitative data collection and a nested qualitative case study, will be briefly described.

Sample

A total of 155 randomly selected fee-for-service (FFS) practices that were eligible for this study and all known and eligible practices that were family health networks (FHNs; n = 94), community health centres (CHCs; n = 51) and health service organizations (HSOs; n = 65) were approached with an aim to recruit 35 practices for each of these 4 primary care models (see Dahrouge and colleagues16 for a complete description of these models). Practices were recruited through mail invitation with careful follow-up. A target of 50 completed patient surveys collected from each recruited practice was set. This sample size was based on that determined for the larger COMP-PC study.16 Patients from eligible practices were recruited sequentially in the practice’s waiting room by a research associate as they presented for their appointment with their primary care provider. Practice and patient eligibility criteria are described in detail in Dahrouge and colleagues.16

For the qualitative case study, we purposefully selected 2 typical practices per model. In each practice, we conducted semi-structured interviews with between 1 and 4 family physicians. In the 2 CHCs and HSOs we also interviewed nurse practitioners. Finally, 6 of the 50 selected patients who completed a patient survey at each site were also interviewed (see below).

Instruments

Practice, provider and patient surveys were developed for this study, all of which were adapted from the Primary Care Assessment Tool (PCAT)-Adult edition.17,18 All were self-completed. The patient survey was divided into 2 sections. The first was completed in the waiting room before the visit with the provider and captured descriptive information about the patient. The second was completed in the waiting room after the patient’s appointment and captured visit-specific information, including information about waiting time, visit duration and health promotion. A 7-item question addressed health promotion activities; it was adapted from the PCAT and is consistent with the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care.12 The question asked, “In today’s visit to your clinic were any of the following subjects discussed with you?” Seven topics were listed (healthy food, home safety, family conflict, exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption and fall prevention (for patients 65 years of age and older); participants had the option of responding “yes,” “no” or “don’t know” for each topic. The survey was available in French and English, and translators were used to assist individuals not literate in either language in completing the survey. Provider and practice surveys were completed by the provider and practice manager respectively, and were retrieved from the practice by the research associate during data collection or mailed back to the research centre by the respondent. The guides provided for the in-depth interviews of family physicians, nurse practitioners and patients comprised open-ended questions about health promotion processes at the practice level, were available in French and English, and differed in content depending on the type of respondent (patient or provider). A copy of the surveys is available from the authors upon request.

Analysis

Our principal binary outcome measure was whether the patient reported discussing at least 1 health promotion subject, termed here health promotion discussed (HP-discussed). We also measured the number of health promotion items discussed (0–7), termed health promotion count (HP-count).

Descriptive and bivariate analyses

Descriptive analyses detailing patient and practice profiles across models were performed. Multilevel binary logistic analyses were used to evaluate the bivariate relationships between patient profile, family physician profile and practice factors and HP-discussed. These analyses were repeated for each model individually to evaluate the transferability of the results across models.

Comparing the primary care models

The performance of the 4 models in delivering health promotion was compared using multilevel logistic (HP-discussed) and Poisson (HP-count) regressions. These regressions were carried out unadjusted and adjusted for patient characteristics and contextual factors with and without family physician factors. Variables with a significance level below p < 0.05 in the bivariate analyses were retained. In each case, we also assessed the presence of interaction between these factors and the model variables. To avoid case-wise deletion, missing values in continuous predictors were imputed with the nearest neighbourhood technique, and missing discrete variables formed a separate category.

Evaluating practice factors independently associated with health promotion performance

We conducted multivariate binary logistic regression of variables reported in Tables 1 and 2 to evaluate factors independently associated with HP-discussed, and we assessed their value in predicting HP-count using Poisson regressions. Variables with a significance level below p < 0.05 in the multivariate analyses were retained.

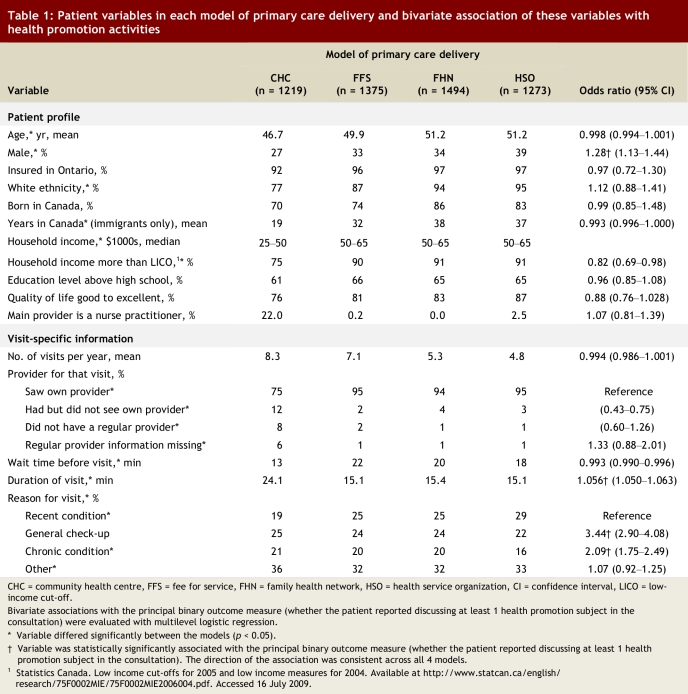

Table 1.

Patient variables in each model of primary care delivery and bivariate association of these variables with health promotion activities

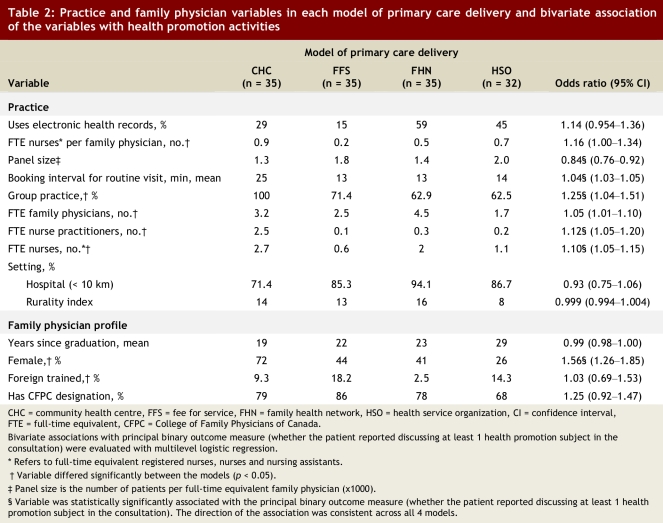

Table 2.

Practice and family physician variables in each model of primary care delivery and bivariate association of the variables with health promotion activities

Qualitative analysis

Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed verbatim, then coded and analyzed with the support of NUD*IST 6 software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). We used a coding tree informed by the literature on primary care organizations. This was then refined through an iterative process using an open coding strategy.19 Subsequent analysis involved axial and selected coding to explore interconnections between existing categories and subcategories.20 Finally, we used an immersion–crystallization approach21 to identify and articulate the themes and patterns emerging from the empirical dataset.

Results

Descriptive and bivariate analyses

Thirty-five FFS, FHN and CHC practices and 32 HSO practices were recruited. An analysis that used the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database and the Ontario Physician Manpower database to compare the physicians recruited for this study with all physicians practising in the same model showed little differences for key features.16 The overall patient response rate was 82% (range 77%–94%), and 4861 patients (91%) responded to the health promotion question . In-depth interviews were conducted with 40 family physicians, 6 nurse practitioners and 24 patients.

There was considerable variability in patient, provider and practice profiles across models (Tables 1 and 2). Several factors had a significant association with the HP-discussed measure that were consistent across models.

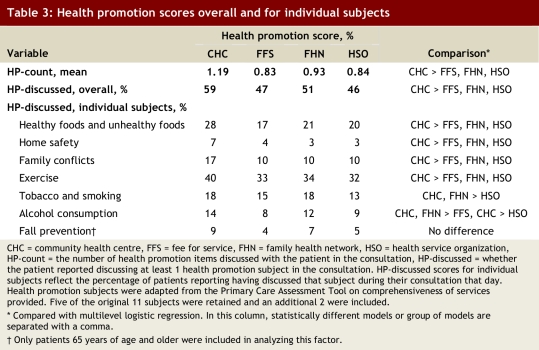

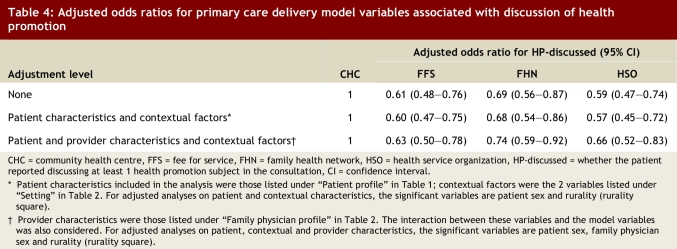

Comparison of primary care delivery models

The likelihood of a health promotion subject being discussed and the number of subjects discussed in the reference visit were significantly higher in CHC practices than in practices in the other models. Several health promotion subjects were more likely to have been discussed in a CHC visit (Table 3). CHC performance remained superior in the regressions adjusted for patient factors and provider profile for HP-discussed (Table 4) and HP-count (results not shown) in the multivariate multilevel logistic regression. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of HP-discussed in practices in the other primary care delivery models compared with CHCs ranged between 0.63 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.50–0.78) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.59–0.92). CHC patients also reported more frequent visits to their practice during the year (8.3 v. 4.8–7.1 visits) than patients of practices in other models, which increased the overall likelihood that they would have a discussion about a health promotion subject with their health care provider.

Table 3.

Health promotion scores overall and for individual subjects

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios for primary care delivery model variables associated with discussion of health promotion

Predicting health promotion performance

Several factors were independently associated with HP-discussed (Table 5). In this equation, the addition of the primary care model variable did not add significant explanatory power, indicating that much of the reason for model variation has been captured in the equation. Health promotion activity was reported more frequently by patients enrolled with practices with larger proportions of female family physicians (AOR 1.38, 95% CI 1.15–1.66) and practices employing more nurses (AOR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12). The booking interval for a regular visit was positively associated with health promotion (AOR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.04); each 10-minute increment was associated with a 30% increase in HP-discussed. Smaller family physician panel sizes (number of patients in the care of a full-time equivalent family physician) were positively associated with HP-discussed in a linear fashion (AOR 0.92, 95% CI 0.85–1.01); patients of practices in which each family physician managed a caseload averaging 1500 patients were 8% more likely to discuss a health promotion subject than those enrolled in practices serving 2500 patients per family physician. The size of the physician panel was inversely related to the booking interval. When booking interval is removed from the equation, the effect of panel size becomes statistically significant (AOR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.97).

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios of factors independently associated with health promotion

Finally, health promotion was lower among patients not visiting with their own provider (AOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43–0.78) and higher among those receiving a general checkup (AOR 3.34, 95% CI 2.81–3.97) or care for a chronic condition (AOR 2.03, 95% CI 1.69–2.43). The association between each of the predictive variables and HP-discussed in this multivariate equation was consistent across all models. All factors except not having a regular provider were also positively independently associated with HP-count.

Qualitative evaluation

Results of the qualitative evaluation illuminated the quantitative findings. Compared with the physicians interviewed in CHCs, those in FFS practices, FHNs and HSOs tended to view health promotion as having a lower priority than other issues to be addressed in patient visits. Constrained by time and preoccupied by the tyranny of the urgent, a number of these physicians doubted their ability to meaningfully influence issues that many saw as a patient’s own responsibility. Time constraints were mentioned repeatedly. One family physician from an FFS practice commented, “So I try to do the preventive stuff of you know women’s health … education of lifestyle, we try to do all of that. Time is a limiting factor. Would I like to do more? Yes. Can I afford to do more economically or realistically with the number of patients that I have? No.” Physicians in FFS practices, FHNs and HSOs valued relational continuity; they felt that health promotion can be effective even at a “low dose” if it is done in the context of a long, exclusive and trusting patient–physician relationship. Indeed, a number of physicians expressed anxiety about the implications of the loss of relational continuity that may follow a move to team-based care.

In contrast, physicians working in collaborative models of care (CHCs and 1 interdisciplinary HSO) were more likely to view health promotion as an integral part of primary patient care. They valued the varied contributions of members of an inter-professional team in encouraging patient-centred behavioural change. As one family physician at a CHC suggested, “And very often, other professionals are much better at doing the health education and health promotion. For me to take somebody and have a chat about cholesterol versus a dietitian, if the dietitian is available, which is much cheaper than me, it makes sense to me.”

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the performance of primary care models in delivering health promotion and to identify practice factors associated with the delivery of health promotion. CHCs performed better than the other models in the delivery of health promotion. These results mirror those of an earlier study that relied on provider-reported measures of health promotion within CHCs, FFS practices and HSOs in Ontario,22 but they are inconsistent with the results of Hutchison and colleagues, who found that delivery of preventive and health promotion activities was superior in a salary-based model and a capitation-based model (HSOs) to that in the traditional FFS model.14 As suggested by our interviews, CHCs place more importance on health promotion than other models. It seems likely that their pattern of service delivery has evolved in concert with their mandate: CHCs emphasize wellness and prevention and incorporate clinic-based interventions to address the non-medical determinants of health.23

Practice influences on prevention

The model of primary care delivery did not independently predict health promotion activity in the multivariate model containing patient, family physician and organizational factors. The relationship between the predictive factors and health promotion remained true for each model, indicating not that the effect of these factors is due to an association with better performing models but rather that their impact would hold true across models.

These results help explain the observed differences between the models. CHCs work with smaller panel sizes, more nurses, longer booking intervals and a much higher proportion of female family physicians (nearly 3 times higher than in the FFS practices): all of these factors increase the likelihood that health promotion activities will be conducted. These factors outweighed any negative influence of lower relational continuity observed in CHCs.

Physician concerns about loss of continuity were reflected in another Canadian study as a barrier to integrating prevention into daily practice.24 In our study, patients were significantly more likely to report discussing a health promotion subject during a visit with their regular provider, independent of the reason for the visit, than were patients visiting a provider who is not their regular provider. These results are consistent with those of other studies documenting a positive association between relational continuity and preventive care.25-30 Our findings that female family physicians are more likely to provide preventive services are consistent with those of other studies.31-33 Longer booking intervals and smaller caseloads were also found to be positively associated with health promotion in 1 other study34 and this finding is in keeping with recent work highlighting the time burden of delivery of preventive services in primary care.35,36 If one assumes that the amount of time to be worked by health professionals remains constant, smaller patient caseloads and longer booking intervals have clear implications for the provision of quality care.

One assumption that has been made in connection with efforts to reform the delivery of primary care is that routine tasks could be better managed by non-physician health professionals. Our finding that the number of nurses in a practice was an independent predictor of patient-reported health promotion supports this assumption. The most likely explanation for our finding is that nurses perform health promotion activities in some practices. An English study found that patients were receptive to receiving lifestyle advice from nurses.37 The findings are of particular importance in light of the current interest in primary care reform. Most Canadian provinces are engaging in an active process of primary health care renewal,38 much of it focused on organizational and economic changes designed to increase the comprehensiveness, integration and accessibility of primary care services. New delivery models frequently incorporate interdisciplinary teams, patient enrolment and active promotion of prevention and chronic disease management.7 In Ontario, family health teams were recently developed to deliver primary care, and the contribution of allied health professionals is a key component of this new model.39 Family health teams are practices that have received provincial financial support for allied health professionals to assist in the care of the population they serve. Nurses will form a significant part of that workforce and may be influential in promoting healthy lifestyles. Surprisingly, although a significant component of nurse practitioners’ training concerns the delivery of health promotion and wellness care, the presence of nurse practitioners in a practice was not associated with better health promotion in our study.

Limitations

This study has a number of strengths and limitations. It provided rich information about practice parameters, providers and patients that allowed an in-depth evaluation of many of the factors associated with health promotion activities. Data were collected from a large, random sample of practices. The study used qualitative methods to illuminate many of its findings.

Participation by practices was low, particularly in the case of the FFS practices. However, a comparison of family physician profiles in the practices that participated in this study and in all practices of the same model in Ontario suggested that the study sample was representative (results not shown).16

Because many health promotion activities performed by providers are not routinely recorded in the patient’s chart, we relied on patient reports of health promotion activities. We limited recall bias by administering this component of the questionnaire immediately after the patient’s encounter with their provider. The question capturing health promotion activities was broadly worded so that we could capture any discussion of 1 of the 7 measured items. We were not able to evaluate the quality of these discussions. We also did not capture information about the patients’ lifestyle (e.g., smoker, physically active) and could not correct for its impact on health promotion discussions. We chose to administer the patient survey to those patients visiting the practice on a given day. This face-to-face approach likely enhanced participation but admittedly resulted in an overrepresentation of the patients more likely to frequent the practice. Other provider factors found to be associated with health promotion in other studies, such as their awareness of and agreement with clinical practice guidelines,25,40 their self-perceived ability to affect behaviour24,41 and their personal health behaviours,35 were not evaluated in the present study. These factors could have had an impact on our conclusions if they had varied by model.

In conclusion, there was a significant difference between models of primary care delivery in terms of health promotion activities, as measured by patient reports of the delivery of such activities within their consultation with their provider. The effects of factors associated with the organization of the practice and visit-specific information outweighed the effects of any additional factors associated with the model of the practice.

Several of the factors associated with health promotion delivery during a patient encounter are potentially modifiable by either the practice or regulatory authorities. Notwithstanding this, any potential benefits from modifications to practice structure stemming from the findings of this study should be weighed against their potential impact on other attributes of primary care delivery. For example, limiting the caseload of family physicians may improve health promotion but would also limit accessibility.

Biographies

William Hogg is a professor at the Department of Family Medicine, the Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, and the Institute of Population Health, the University of Ottawa, and director of the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre, Ottawa, Ontario.

Simone Dahrouge is manager of Research Operations at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre.

Grant Russell is an associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and the Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, and a principal scientist at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre.

Meltem Tuna is a research associate at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre.

Robert Geneau is a scientist at the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Laura Muldoon is a lecturer in the Department of Family Medicine and an affiliate scientist at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre.

Elizabeth Kristjansson is a principal scientist at the Institute of Population Health.

Sharon Johnston is an assistant professor at the Department of Family Medicine, University of Ottawa, and a principal scientist at the C.T. Lamont Primary Health Care Research Centre.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: Funding for this research was provided by the Primary Health Care Transition Fund of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The views expressed in this report are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Contributors: William Hogg, Laura Muldoon, Elizabeth Kristjansson, with others, conceived the study and oversaw its implementation. They also helped with the analysis and participated in writing the article. Grant Russell helped oversee the implementation of the project, helped guide the analysis and participated in writing the article. Simone Dahrouge was responsible for the quantitative data collection and analysis and participated in writing the article. Robert Geneau was responsible for the qualitative data collection and analysis and participated in writing the article. Meltem Tuna performed the data analysis and participated in writing the article. Sharon Johnston helped guide the analysis and participated in writing the article. All of the authors approved the final version to be published.

References

- 1.Federal, Provincial and Territorial Advisory Committee on Population Health. Statistical Report on the Health of Canadians. Rev Mar 2000. Ottawa: Health Canada, Statistics Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanmartin C, Ng E, Blackwell D, Gentleman J, Martinez M, Simile C. Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health. Ottawa: Minister responsible for Statistics Canada in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor Benjamin, Rehm Jürgen, Patra Jayadeep, Popova Svetlana, Baliunas Dolly. Alcohol-attributable morbidity and resulting health care costs in Canada in 2002: recommendations for policy and prevention. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(1):36–47. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein Eric A, Fiebelkorn Ian C, Wang Guijing. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: how much, and who's paying? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(4):8–22. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.219. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14527256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weingarten S. Using practice guideline compendiums to provide better preventive care. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(5):454–458. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-5-199903020-00023. http://www.annals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10068430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Building on values: The future of health care in Canada — Final Report. 2002. http://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=237274&sl=0.

- 8.Patterson C, Chambers L W. Preventive health care. Lancet. 1995;345(8965):1611–1615. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fries J F, Koop C E, Beadle C E, Cooper P P, England M J, Greaves R F, Sokolov J J, Wright D. Reducing health care costs by reducing the need and demand for medical services. The Health Project Consortium. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(5):321–325. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307293290506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wechsler H, Levine S, Idelson R K, Schor E L, Coakley E. The physician's role in health promotion revisited — a survey of primary care practitioners. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(15):996–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Effective dissemination and implementation of Canadian task force guidelines on preventive health care: literature review and model development. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. New grades for recommendations from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 2003;169(3):207–208. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12900479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchison B G, Abelson J, Woodward C A, Norman G. Preventive care and barriers to effective prevention. How do family physicians see it? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1693–1700. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=8828872. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchison B, Woodward C A, Norman G R, Abelson J, Brown J A. Provision of preventive care to unannounced standardized patients. CMAJ. 1998;158(2):185–193. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=9469139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogg William, Rowan Margo, Russell Grant, Geneau Robert, Muldoon Laura. Framework for primary care organizations: the importance of a structural domain. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Nov 30;20(5):308–313. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm054. http://intqhc.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18055502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahrouge S, Hogg W, Russell G, Geneau R, Kristjansson E, Muldoon L, Johnston S. The Comparison of Models of Primary Care in Ontario study (COMP-PC): methodology of a multifaceted cross-sectional practice-based study. Open Med. 2009;3(3):149–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starfield B Primary Care Policy Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool - Expanded Version. Self-Administered Client-Patient Tool. 1998. http://www.jhsph.edu/pcpc/pca_tools.html.

- 18.Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the adult primary care assessment tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):E1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oakes (CA): Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles MB, Huberman MA. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WL, Crabtree B. Doing qualitative research. Newbury Park: Sage; 1992. Primary care research: a multimethod typology and qualitative road map; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abelson J, Lomas J. Do health service organizations and community health centres have higher disease prevention and health promotion levels than fee-for-service practices? CMAJ. 1990;142(6):575–581. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=2311035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Association of Ontario Health Centres. Handbook for developing a community health centre - Phase I: Getting started: Organizing the community. 2000. http://www.aohc.org/app/DocRepository/2/Need_help_becoming/Phase_One_2000.pdf.

- 24.Hudon Eveline, Beaulieu Marie-Dominique, Roberge Danièle Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Integration of the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care: obstacles perceived by a group of family physicians. Fam Pract. 2004;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh104. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14760037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract. 2004;53(12):974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safran DG, Miller W, Beckman H. Organizational dimensions of relationship-centered care. Theory, evidence, and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S9–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00303.x. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16405711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saultz John W, Lochner Jennifer. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):159–166. doi: 10.1370/afm.285. http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15798043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steven ID, Dickens E, Thomas SA, Browning C, Eckerman E. Preventive care and continuity of attendance. Is there a risk? Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27(Suppl 1):S44–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Fiscella K. Preventive care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez Hector P, Rogers William H, Marshall Richard E, Safran Dana Gelb. Multidisciplinary primary care teams: effects on the quality of clinician-patient interactions and organizational features of care. Med Care. 2007;45(1):19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241041.53804.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franks P, Bertakis KD. Physician gender, patient gender, and primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12(1):73–80. doi: 10.1089/154099903321154167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim Catherine, McEwen Laura N, Gerzoff Robert B, Marrero David G, Mangione Carol M, Selby Joseph V, Herman William H. Is physician gender associated with the quality of diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1594–1598. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1594. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15983306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton P G, Dunn E V, Soberman L. What factors affect quality of care? Using the Peer Assessment Program in Ontario family practices. Can Fam Physician. 1997;43:1739–1744. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=9356754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell S M, Hann M, Hacker J, Burns C, Oliver D, Thapar A, Mead N, Safran D G, Roland M O. Identifying predictors of high quality care in English general practice: observational study. BMJ. 2001;323(7316):784–787. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.784. http://bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11588082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kloppe P, Brotons C, Anton J J, Ciurana R, Iglesias M, Piñeiro R, Fornasini M. Preventive care and health promotion in primary care: comparison between the views of Spanish and European doctors. Aten Primaria. 2005;36(3):144–151. doi: 10.1157/13077483. http://www.elsevier.es/revistas/0212-6567/36/144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yarnall KSH, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=12660210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duaso Maria Jose, Cheung Philip. Health promotion and lifestyle advice in a general practice: what do patients think? J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(5):472–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Health Canada. Primary Health Care and Health System Renewal. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2004. [accessed 23 July 2009]. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/prim/renew-renouv-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muldoon Laura, Rowan Margo S, Geneau Robert, Hogg William, Coulson David. Models of primary care service delivery in Ontario: why such diversity? Healthc Manage Forum. 2006;19(4):18–23. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGinnis J M, Hamburg M A. Opportunities for health promotion and disease prevention in the clinical setting. West J Med. 1988;149(4):468–474. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=3067449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirand Amy L, Beehler Gregory P, Kuo Christina L, Mahoney Martin C. Physician perceptions of primary prevention: qualitative base for the conceptual shaping of a practice intervention tool. BMC Public Health. 2002 Aug 30;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-2-16. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/2/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]