Abstract

The authors report here the case of a patient with severe deficits in arousal and sustained attention, associated with hemispatial neglect. These impairments were secondary to acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, with bilateral involvement of the medial nuclei and pulvinar of the thalamus. Treatment with the noradrenergic agonist guanfacine, previously used for attention deficits in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and stroke, was associated with a significant amelioration of both the spatial and sustained attention impairments in neglect. Guanfacine may prove to be a useful tool in the treatment of disorders of attention associated with neurological conditions.

Keywords: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neglect, norepinephrine, sustained attention, thalamus, attention, clinical neurology, neuropharmacology, rehabilitation

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is a relatively rare neuroinflammatory disorder associated with multifocal lesions, frequently preceded by a viral prodrome. It is usually a monophasic illness, with many patients recovering well, although up to half followed up long-term have been reported to have persistent neurological deficits.1 MRI usually reveals asymmetrical subcortical white-matter involvement. However, the deep grey-matter nuclei, such as the thalamus and basal ganglia, may also be affected.2

There are few studies documenting the cognitive and neuropsychological sequelae of ADEM,3 4 with most focussing on motor disabilities. Here, we report a patient with thalamic lesions secondary to ADEM, causing persistent left-sided hemispatial neglect (failure to attend to stimuli in contralesional space) and difficulty sustaining attention. These deficits were subsequently ameliorated by administration of the noradrenergic agonist guanfacine, a drug that has been shown to have positive effects in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder,5 as well as sustained and spatial attention deficits in some patients with neglect secondary to stroke.6

Case report

A 38-year-old male presented with a right-sided facial droop and hemiparesis following a 2-week prodrome of headache, fever, cough and right hemisensory symptoms. Soon after admission, he developed tonic–clonic seizures, necessitating treatment with phenytoin, intubation and ventilation. MRI revealed patchy signal changes in the thalamus, cerebellum, temporal and occipital lobes bilaterally, while MR angiogram revealed normal extra- and intracranial blood flow. Cerebrospinal fluid examination, vasculitic blood screen and transoesophageal echocardiogram were normal. Electroencephalography demonstrated features consistent with encephalopathy, and a diagnosis of ADEM was made. He subsequently received two courses of intravenous methylprednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange and antibiotics. He was also anticoagulated for a deep venous thrombosis and required surgical treatment for an associated compartment syndrome.

The patient remained in intensive care, due to persistent epileptiform activity, for 4 months, when seizures were stabilised on a regimen of levetiracetam 2 g, phenytoin 700 mg and prednisolone 30 mg. He was then transferred to a rehabilitation unit, at which time he had a tetraparesis, with predominant left-sided weakness.

Neuropsychological testing also revealed significant cognitive impairments, including left-sided neglect (with intact visual fields on confrontation), reduced arousal and difficulty sustaining attention. In addition, there were significant impairments in verbal memory (chance performance on the short and easy Recognition Memory Test for verbal material and low average performance on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Span subtest) and naming (5/15 correct on Graded Naming Test). There was also evidence of dysfunction on tests of executive function (concrete performance on Proverb Interpretation and perseveration on Single Letter Reading and the Similarities subtest of the WAIS-R). On the basis of educational and occupational background, he was estimated to have been functioning in at least the superior range premorbidly and had therefore suffered severe intellectual deterioration.

Admission for reassessment occurred 2 years later, at which time anticonvulsant medication consisted of levetiracetam 750 mg and gabapentin 300 mg both twice daily (the total daily dose of levetiracetam was 1250 mg at 6 months' follow-up, with a further reduction to 1000 mg 10 months later). Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a mild left-sided facial weakness. Examination of the limbs revealed a severe hemiparesis with increased tone on the left and a pyramidal distribution of weakness, worse distally. The limb reflexes were all brisk with bilaterally extensor plantar responses. There was severe left hemispatial neglect and impairments in sustained attention and arousal, with the patient spending 20 h a day in bed due to drowsiness. A decision was taken to trial the alpha-2-noradrenergic agonist guanfacine, with the hypothesis that this might improve these cognitive impairments.

Assessment measures

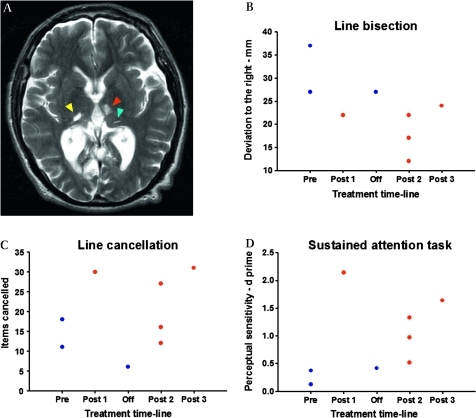

MRI was repeated to determine the extent of lesions (figure 1A). Two standard bedside neuropsychological tests were used to assess neglect, while a computerised task was used to measure the deficit in sustained attention. The neglect tests used were line cancellation, in which subjects are instructed to cancel all the lines they can find (total 40) distributed across an A4 sheet of paper and bisection of 17 cm horizontal lines, where the mean deviation rightwards from centre was taken from three attempts. The computerised task which has been used previously7 was presented on a Dell Latitude D820 laptop computer, and entailed the subject depressing the central button on a response box (RB-530 Cedrus Corp.), whenever an infrequently occurring black circle (8 mm diameter) occurred. The circle remained on the screen for 1 s and was presented on a grey background with interstimulus intervals of 1–7 s. 100 stimuli were presented over a total period of 8 min.

Figure 1.

Bilateral thalamic lesions associated with hemispatial neglect and impaired sustained attention, and amelioration with guanfacine. (A) Bilateral thalamic lesions as demonstrated by T2-weighted MRI scanning. The red arrow indicates one of the left-sided lesions, involving the medial thalamic nuclei, including the medio-dorsal nucleus. There are also smaller adjacent lesions in the pulvinar (blue arrow). The yellow arrow indicates the right-sided lesion, which is also in the pulvinar. (B) Line bisection. The rightward deviation on bisecting 17 cm lines decreased significantly after commencement of guanfacine (deviation given in mm). (C) Line cancellation. The total number of lines cancelled by the patient increased on 2 mg of guanfacine. (D) Perceptual sensitivity on the sustained attention task improved significantly on guanfacine treatment. Pre, preguanfacine; Post 1, initial assessment after commencement of 2 mg of guanfacine; Off, assessment at 2 months after guanfacine had been ceased for 2 weeks; Post 2, assessments at 6 months after initiation of guanfacine; Post 3, assessment at 16 months after initiation of guanfacine.

Responses quicker than 100 ms were classified as anticipations, and therefore as commission errors, as were responses occurring more than 1600 ms after target onset. Perceptual sensitivity, or d′, which is derived from signal detection theory8 and takes into account commission as well as omission errors, was the behavioural outcome measure of this task and calculated according to the formula below:

where H is the hit rate, and F is the false alarm rate. The higher this value, the better the subject was at accurately detecting targets.

These tests were performed on two consecutive days prior to commencing guanfacine, as well as at several time points after its introduction. The dose of guanfacine was titrated up slowly over 3 days in the following increments: 0.5 mg, 1 mg and 2 mg as single daily doses. The first on-guanfacine testing session was performed the day 2 mg was reached.

An additional testing session off-guanfacine was performed 2 months later (due to initial difficulty obtaining the drug locally) at which point the patient had not received guanfacine for 2 weeks. Three on-guanfacine testing sessions were performed 6 months after the initial commencement of 2 mg of guanfacine daily, and a final session occurred a further 10 months later. Therefore, in total, the patient underwent three testing sessions off and five on guanfacine. Testing was always performed during the afternoon.

Guanfacine has previously been well tolerated in studies investigating its efficacy in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; however, the most commonly experienced side effects include drowsiness, sedation and dizziness.5 9 The patient reported here did not experience any side effects.

Results

Figure 1A demonstrates the thalamic lesions on T2-weighted MRI, along with performance on attention tests on and off guanfacine. The thalamic lesions localise to the medial thalamic nuclei (including the mediodorsal nucleus) and pulvinar on the left and to the pulvinar on the right.10 Lesions of the right pulvinar have previously been linked to the pathogenesis of neglect,11 while the patient's remaining small lesions (in the cerebellum, temporal and occipital lobes) all lie outside areas commonly associated with the syndrome, such as the inferior parietal lobe, temporoparietal junction and inferior frontal lobe.12 13

All three measures used to assess attention deficits improved on guanfacine. Permutation testing was used to investigate whether these effects were statistically significant. This established procedure has specifically been used in single-case designs and works by considering all possible recombinations of the data.14 The purpose of considering these recombinations or permutations is to attempt to account for fluctuations in assessment scores which may occur over time, unrelated to the effects of treatment.

First, the difference between the actual baseline and treatment means is calculated. Then, the mean difference for every other possible combination of data if the treatment had been introduced at different time points in the data set is computed. In other words, imagine that you were given the results without knowing when the patient was on or off a drug. One could look at all the different permutations of being on and off a drug and calculate the mean difference in performance for each of these permutations.

If the difference between actual on- and off-treatment means is greater than that for any other combination, it is possible to calculate how often this would happen by chance. In general, the actual difference between means will be statistically significant at the 5% level, if this difference falls in the 5% most extreme differences in the distribution of possible recombinations of the data.14

In this case, the total number of permutations for our three off- and five on-treatment observations is 56. Therefore, if the difference between actual on- and off-treatment means is greater than the mean difference for all the other possible recombinations of the dataset, the probability of this occurring purely by chance is 1/56=0.018.

This analysis revealed that rightward deviation on line bisection reduced significantly (figure 1B) after commencing guanfacine (p=0.018), demonstrating clear amelioration of the spatial bias most characteristic of neglect. The number of items identified on line cancellation also increased (figure 1C), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.071). On the other hand, accurate target detection (perceptual sensitivity) over the 8 min computerised sustained attention task was significantly enhanced (p=0.018, figure 1D), revealing that, in addition to ameliorating aspects of the spatial bias of neglect, guanfacine was able to improve the deficit in sustained attention.

Clinical observation was consistent with these data, with the patient's general level of alertness and arousal improving following introduction of guanfacine. Furthermore, after a period of 6 months on the drug, his carers reported an ‘improvement in his awareness and conversation…’ to the extent that he was able to ‘…contribute significantly to crossword puzzles and enjoy his music CDs.’ As a result of these persistent benefits, the patient continues to take 2 mg guanfacine daily.

Discussion

The case presented here demonstrated severe hemispatial neglect and impairments in sustained attention, associated with bilateral thalamic lesions caused by ADEM. Initiation of the noradrenergic agonist guanfacine led to an improvement of these deficits, which persisted with continued guanfacine use. Thalamic lesions, especially those involving the medial nuclei—including the medial pulvinar—are most frequently associated with deficits in arousal, which can be particularly severe following bilateral damage, as can occur following stroke.10 Hemispatial neglect is also often reported, again following strokes involving the medial thalamus and pulvinar, most frequently in the right hemisphere.10 11 15 In contrast, these impairments have rarely been referred to in the literature as a sequela of ADEM.3

Difficulty with arousal or maintaining alertness, so that attention can be sustained on current goals, is increasingly accepted as a component of the neglect syndrome, capable in fact of predicting the severity of the spatial bias.16 It has been proposed that arousal is dependent on noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus to inferior parietal and frontal cortex, and indirectly to these regions via the thalamus.15 Damage to these regions can also be associated with neglect.11–13

Further evidence of the intimate link between arousal and the spatial orientation of attention comes from rehabilitation studies. Alertness training can improve neglect,17 while single doses of guanfacine have previously been shown to enhance sustained attention, in addition to ameliorating the spatial deficit.6 Although continued guanfacine use has been demonstrated to be efficacious in the treatment of inattentiveness in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,5 this is the first demonstration of a persistent amelioration of at least some components of the spatial deficit of neglect with a noradrenergic agonist.

Footnotes

Funding: This research is supported by The Wellcome Trust and the NIHR CBRC at UCLH/UCL.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the UCLH/UCL.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Schwarz S, Mohr A, Knauth M, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology 2001;56:1313–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernarding J, Braun J, Koennecke HC. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted MR imaging in a patient with acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM). J Magn Reson Imaging 2002;15:96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunnerhagen KS, Johansson K, Ekholm S. Rehabilitation problems after acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: four cases. J Rehabil Med 2003;35:20–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollinger P, Sturzenegger M, Mathis J, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in adults: a reappraisal of clinical, CSF, EEG, and MRI findings. J Neurol 2002;249:320–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biederman J, Melmed RD, Patel A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2008;121:E73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malhotra PA, Parton AD, Greenwood R, et al. Noradrenergic modulation of space exploration in visual neglect. Ann Neurol 2006;59:186–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhotra P, Coulthard EJ, Husain M. Role of right posterior parietal cortex in maintaining attention to spatial locations over time. Brain 2009;132:645–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanislaw H, Todorov N. Calculation of signal detection theory measures. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput 1999;31:137–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt RD, Arnsten AF, Asbell MD. An open trial of guanfacine in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:50–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmahmann JD. Vascular syndromes of the thalamus. Stroke 2003;34:2264–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karnath HO, Himmelbach M, Rorden C. The subcortical anatomy of human spatial neglect: putamen, caudate nucleus and pulvinar. Brain 2002;125:350–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mort DJ, Malhotra P, Mannan SK, et al. The anatomy of visual neglect. Brain 2003;126:1986–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husain M, Kennard C. Visual neglect associated with frontal lobe infarction. J Neurol 1996;243:652–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todman J. Randomisation in single-case experimental designs. Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil 2002;2:18–19 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson RT, Valenstein E, Heilman KM. Thalamic neglect. Possible role of the medial thalamus and nucleus reticularis in behavior. Arch Neurol 1981;38:501–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson IH, Manly T, Beschin N, et al. Auditory sustained attention is a marker of unilateral spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia 1997;35:1527–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturm W, Thimm M, Kust J, et al. Alertness-training in neglect: behavioral and imaging results. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2006;24:371–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]