Abstract

In the mid-nineteenth century, almost 70 percent of persons age 65 or older resided with their adult children; by the end of the twentieth century, fewer than 15 percent did so. Many scholars have argued that the simplification of the living arrangements of the aged resulted primarily from an increase in their resources, which enabled increasing numbers of elders to afford independent living. This article supports a different interpretation: the evidence suggests that the decline of coresidence between generations had less to do with the growing affluence of the aged than with the increasing opportunities of the younger generation. Using data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), I examine long-run trends in the characteristics of both the older and the younger generations to gain insight into changing motivations for coresidence. In particular, I investigate headship patterns, occupational status, income, and spatial coresidence patterns. I also reassess the potential impact of the Social Security program. I conclude that the decline of intergenerational coresidence resulted mainly from increasing opportunities for the young and declining parental control over their children.

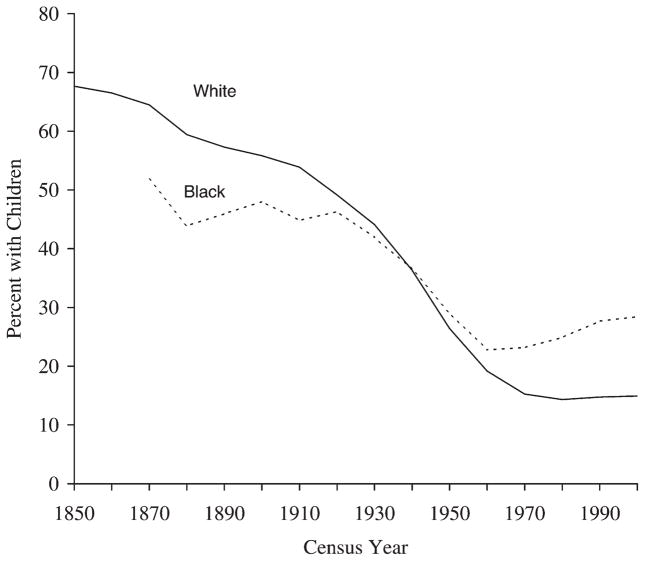

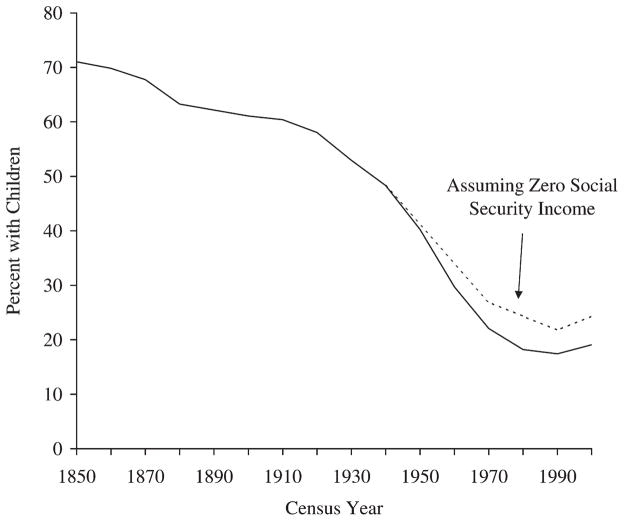

During the past century and a half, the living arrangements of the aged in the United States shifted dramatically. The dimensions of change are illustrated in Figure 1. In 1850, two-thirds of whites age 65 or older lived with an adult child. The percentage of elderly whites residing with adult children declined steadily from 1850 to 1980, reaching a nadir of 13 percent in 1990 before rising slightly in 2000. Among blacks, the trend was less dramatic but still sizeable; coresidence fell from 50 percent in 1870 to 22 percent a century later.1 The transformation of the living arrangements of the aged was equally dramatic among unmarried men, unmarried women, and married couples, although there was slight variation in the timing of change (Ruggles 2003).

Figure 1.

Percent of Persons Age 65+ Residing with Their Own Children Age 18+; United States Whites and Blacks, 1850 to 2000

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

This article examines explanations for this remarkable simplification of U.S. family structure. I assess historical evidence from the census to uncover clues about the formation of intergenerational families and the incentives for both the older generation and the younger generation to reside together. I argue that scholars have overemphasized the effects of rising income of the older generation and underestimated the role of growing economic independence of the younger generation. More broadly, I argue that the decline of intergenerational coresidence reflects a decline of patriarchal control brought about by the rise of wage labor and the decline of agriculture.

THE AFFLUENCE HYPOTHESIS

There is broad scholarly consensus about the sources of the extraordinary decline in intergenerational coresidence. In the nineteenth century, according to the consensus interpretation, the aged population wanted to reside separately from their children, just as they do today. According to Hareven, for example, people resorted to intergenerational coresidence only in cases of necessity, “primarily when elderly parents were too frail to maintain a separate residence” (1996:1–2; also see Hareven 1994:442). Most social scientists writing on this topic in recent decades agree: nineteenth-century elders preferred independent residence and only moved in with their children when they were infirm or impoverished and had no other alternatives.2 This interpretation usually further assumes that the members of the younger generation moved out of their parental home upon reaching adulthood, and that dependent elders then moved into a child’s household when they could no longer fend for themselves—a viewpoint that Ker tzer (1995) ter ms the “Nuclear Reincorporation” hypothesis.3

The explanation for the dramatic decline in residence with children under this consensus interpretation is straightforward: the rising income of the aged reduced their dependence on children and allowed them finally to achieve their preference for independent living. Goldscheider and Lawton (1998) describe this theory as the “affluence interpretation.” The acceleration of the change after 1940, according to the affluence interpretation, was a response to the introduction of Social Security (Costa 1999; Elman 1998; Engelhardt, Gruber, and Perry 2005; Gratton 1986; Haber and Gratton 1994; Kramarow 1995; McGarry and Schoeni 2000; Michael, Fuchs, and Scott 1980; Smith 1986).

The consensus theory, however, is undermined by historical evidence from the U.S. census. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the poor were not the group most likely to reside in intergenerational families; on the contrary, they were the group most likely to live alone (Ruggles 1996b, 2003). Moreover, nineteenth-century elders with chronic illnesses and disabilities were significantly less likely to reside with children than were healthier elderly people (Ruggles 2003).4 Given that independent residence in the nineteenth century was concentrated among the infirm and the impoverished, all other things being equal, one would expect that the improvements in the health and economic well-being of the aged in the twentieth century would have increased the frequency of intergenerational coresidence.

THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS

Several studies have shown that intergenerational coresidence in the recent past has been more likely to result from the needs of children than from the needs of their elderly parents (Aquilino 1990; Choi 2003; Crimmins and Ingegneri 1990; Kotlikoff and Morris 1990; Ward, Logan, and Spitze 1992; cf. Moehling 1995). This article extends that argument: I maintain that much of the dramatic historical change in the living arrangements of the aged can be traced to the changing circumstances of the younger generation. I further argue that the decline of intergenerational coresidence is linked to the rise of wage labor and mass education and the decline of household-based production. This interpretation echoes the views of earlier generations of social scientists and policy analysts, but it is sharply at odds with the revisionist interpretation of family history that has predominated for the past three decades.

Traditional Interpretations of Family Change

The affluence interpretation of the shift in living arrangements of the aged is of comparatively recent origin. Social observers first began to comment on the decline of intergenerational coresidence in the second half of the nineteenth century, and from that time until the 1960s their explanations for the change hinged mainly on the transformation of the economy. In 1872, Frédéric Le Play argued that a shift from stem families to unstable families was taking place “among the working class populations subject to the new manufacturing system of Western Europe” (Silver 1982:260). In stem families, according to Le Play’s definition, the father selected one child to remain near the parental homestead to work on the farm and eventually inherit it, thus continuing the family line. All other children left the parental family to form their own nuclear households. Growing commercialization and industrialization in the nineteenth century, however, meant that fewer families had property to hand down. As a consequence, Le Play argued, unstable families became common. In unstable families, all the children left home at an early age and established their own households. Elderly parents were left to fend for themselves, and upon their deaths, the family was extinguished (Le Play 1884:3–28).

The idea that the decline of agriculture and the rise of industrial employment had reduced the frequency of intergenerational coresidence became a commonplace of early twentieth-century social theory and policy analysis.5 The creators of the Social Security program uniformly believed that the need for old-age assistance had greatly increased because of the rise of wage labor, the decline of farming, and the resulting changes in the living arrangements of the aged. Thomas H. Eliot, counsel for the committee that drafted the Social Security bill, explained that “in the old days, the old-age assistance problem was not so great so long as most people lived on farms, had big families, and at least some of the children stayed on the farm.” In the early twentieth century, however, “more and more of the young, rural population left the farms … by the time people got old, the children had already left and gone to the city.” Thus, Eliot concluded, there was “an increase in the problem of the needy aged” (Eliot 1961).

Eliot’s interpretation is consistent with that of Le Play, and many other twentieth-century analysts of aging expressed similar ideas (e.g., Burgess 1960; Cowgill 1974; Nimkoff 1962). The hypothesis they articulated differs distinctly from the affluence hypothesis. Le Play, Eliot, and other observers did not believe nineteenth-century intergenerational coresidence came about when aged persons moved in with children for old-age support, and they did not attribute the changes in the living arrangements of the aged to rising incomes. They focused on the changing needs and resources of the younger generation rather than on those of the older generation.

Transformation of the Economy and the Family

A fundamental transformation of employment and production during the past 150 years profoundly reshaped the needs and resources of each generation. The United States was not underdeveloped in the mid-nineteenth century, at least by the standards of the day. America was among the top producers of boots and shoes, cotton textiles, liquor, paper, agricultural implements, guns, and ships. By 1840, more horsepower was generated by steam engines in the United States than in any other county, and more than half of the world’s railroad mileage was in the United States. Improvements in transportation—not just railroads, but also canals and turnpikes—opened vast new tracts of land in the interior to commercial farming. Farmers began to sell most of what they produced, and they used the proceeds to buy all sorts of tools and consumer products they could not previously afford, such as magazines, almanacs, whale-oil lamps, wallpaper, clocks, scissors, and woven cloth. By midcentury, the innovations in manufacturing, transportation, and commerce touched the lives of virtually all Americans (Carter et al. 2006; Engerman and Gallman 2000; Mulhall 1899; Sellers 1991).

Even though the transformation of the economy was well underway, America in 1850 was still fundamentally an agricultural society. Almost 60 percent of the population still lived on farms, and wealth was mainly reckoned in land and slaves. Families grew most of their own food and made most of their own clothes. Despite the early growth of the factory system, even commercial manufacturing still took place mainly within the household: an artisan and his family typically lived together adjacent to the shop where they produced such products as leather goods, flour, or furniture. The system of household production also predominated in the service sector, especially in retail trade (Folbre and Wagman 1993; Lamoreaux 2003; Margo 2000; Shammas 2002).

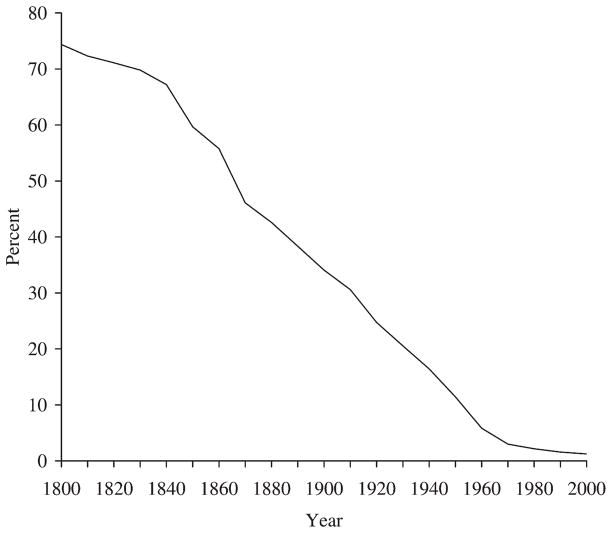

The economic upheaval of the past two centuries is shown vividly in Figure 2, which displays the estimated percentage of the labor force engaged in agricultural work from 1800 to 2000. Employment in agriculture began to fall after 1800, when about 75 percent of the labor force worked in farming. That percentage dropped gradually until 1840, when 67 percent remained in farming. Then the economic transformation took hold in earnest. The three decades from 1840 to 1870 saw the fastest change; the percentage of the labor force in agriculture fell by about 10 points in each of those decades. During the next hundred years, agricultural employment continued to drop steadily, falling some 5 percent per decade. By 1980, only 2 percent of workers remained in farming.

Figure 2.

Percent of the Labor Force Employed in Agriculture, United States, 1800 to 2000

Sources: Weiss 1992:22; Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

The intergenerational family system of mid-nineteenth-century America benefited both the older and younger generations. Farmers and artisans who reached advanced ages could get help with heavy work. The younger generation eventually inherited the farm or business and was assured of a life-long occupation (cf. Berkner 1972; Fauve-Chamoux 1996; Ruggles 1994, 2003). Between 1850 and 1950, this system was shattered by an economic revolution. Jobs in large-scale commerce, manufacturing, and transportation eclipsed agricultural work and self-employed crafts, and this destroyed the economic logic of the traditional patriarchal family. Millions of young people left their parents’ farms, attracted by the high wages, independence, and excitement of town life. When those wage workers then grew old, they were unlikely to live with their children. In each succeeding generation, fewer and fewer fathers were farmers or self-employed craftsmen. Thus, fewer could offer the incentive of occupational inheritance to keep their grown children from leaving home, and fewer had any real need to keep their adult children at home.

Mass education reinforced the effects of wage labor. Schooling helped restructure family relationships by transforming children from an economic asset into an economic burden (Caldwell 1982). Children who spent their days in school reduced their economic contributions to the household. Even in the nineteenth century, schooling began to undermine the traditional family economy. The rise of secondary education in the twentieth century put new pressures on the traditional structure of authority within the family. Increasingly, obtaining a good job depended more on education than on familial connections. Those who graduated from high school had dramatically improved economic opportunities and expanded horizons. By the mid-twentieth century, when secondary education was expanding rapidly, adult children typically had more education and greater earning power than did their parents, and this profoundly altered the economic relationship between generations.

More and more, parents supported their children during an extended period of childhood dependency while their offspring attended school. Like traditional agricultural inheritance, this represented a transfer of assets from the older generation to the younger. But unlike the promise of eventual inheritance of material assets, the education of children did not confer power on the older generation; on the contrary, it empowered the younger generation. Children with education were less likely to work on the family farm or business, more likely to move to the cities to seek their fortunes, and much less likely to reside with elderly parents.

ALTERNATE EXPLANATIONS

In addition to the affluence hypothesis and the economic development hypothesis, social theorists have offered a variety of other explanations for the changing living arrangements of the aged. A full analysis of these alternatives is beyond the scope of this article, but in this section I briefly discuss some of the most influential of these ideas.

Social and Geographic Mobility

Mid-twentieth-century social theorists stressed the impact of high geographic and social mobility on family structure. In particular, structural-functionalists argued that the new industrial system demanded a flexible and mobile family, one that could respond quickly to the changing demands of the modern economy. According to this interpretation, the isolated nuclear family was ideally suited to the fluid and mobile labor market of mid-twentieth-century America (Parsons 1949; Parsons and Bales 1955).

New historical research undermines the hypothesis that rising social and geographic mobility contributed to the decline of intergenerational coresidence. Contrary to the assumptions of mid-twentieth-century sociologists, the new evidence indicates that both occupational mobility and internal migration declined dramatically from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century (Ferrie 2005; Hall and Ruggles 2004). Thus, when intergenerational coresidence was highest, so was economic and geographic mobility. We must therefore reject the hypothesis that mid-twentieth-century nuclear family structure was a response to increased economic and geographic mobility.

Urbanization

Wirth (1938:21) asserted that “the city is not conducive to the traditional type of family life” and the transfer of activities to specialized institutions “has deprived the family of its most characteristic historical functions.” Wirth and other theorists argued that urban institutions undermined the family by taking over traditional family functions, such as economic production, education, and social support. The view that small conjugal families are especially suited to cities was pervasive in mid-twentieth-century sociological theory (e.g., Burgess 1960; Cowgill 1974; Goode 1963).

The historical evidence contradicts the urbanization hypothesis. Multivariate analyses consistently show that urban elders in the early twentieth century were significantly more likely to live with children and less likely to live alone than were their rural counterparts (Costa 1997; Elman 1998; Kramarow 1995; Ruggles 1987, 1996b).6 This difference persists when a wide variety of compositional characteristics are controlled, including immigrant status, demographic characteristics, and local economic conditions. Thus, the urbanization hypothesis apparently cannot help explain the decline of intergenerational coresidence in the twentieth century.

Demographic Change

The measure of intergenerational coresidence used here—percentage of elders residing with adult children—is comparatively insensitive to variation in demographic conditions. The dramatic decline in fertility during the past 150 years means that elderly persons now have fewer children with whom they can reside, and demographers argue that this contributes to declining coresidence (Kobrin 1976; Soldo 1981; Wister and Burch 1983). Demographic analysis, however, suggests that fertility decline can account for little of the long-run change in intergenerational coresidence (Kramarow 1995; Ruggles 1994, 1996b).7 When other compositional changes are controlled—age, sex, and marital status of the elderly population, as well as infant and child mortality—the net direct effects of demographic change on the long-run decline in coresidence of the aged are negligible (Ruggles 1996a, 1996b).

An indirect influence of demographic change on coresidence may arise through changes in the age composition of the population as a whole. With declining fertility and mortality, the population age 65 or older went from just over 4 percent of Americans in 1850 to approximately 17 percent in 2000 (Carter et al. 2006). This means that the percentage of households with the potential to include elderly kin rose steadily from about 12 percent to over 30 percent in the same period (Ruggles 2003; see also Ruggles 1994; Schoeni 1998; Uhlenberg 1996).

Levy (1965) argued that many societies have an ideal of coresidence, but that ideal can only be maintained as long as a small minority of adults actually lives with aged parents. When demographic constraints diminish and coresidence becomes more common, Levy contended that “sources of stress and strain” lead to a shift in the ideal toward nuclear family structure (Levy 1965:49). Kobrin (1976:136) agreed, arguing that “under pressure from demographic changes, residence norms have changed, resulting in a great increase in the proportion of older females who live alone” (cf. Burch 1967; Ruggles 1987). Thus, as the ratio of elderly to adult children increased, the norm of coresidence was undermined by the “stress and strain” of coresidence itself; the demographic transition indirectly led to a transition in residential preferences. This indirect demographic argument may be viewed as part of a broader class of arguments pointing to the influence of shifting tastes and attitudes on family structure.

Attitudinal Change

Cultural theories of the family often stress the indelibility of family values (Therborn 2004), but some theorists posit an independent role for attitudinal change. As noted, Levy (1965) and Kobrin (1976) argued that increased demographic opportunities for coresidence led to a shift in social norms and a decline in the desire for coresidence. Other theorists regard increasing individualism and a growing taste for privacy as a logical outcome of cultural changes set in motion by the Refor mation and the Enlightenment (Lesthaeghe 1983; Stone 1977). Still others offer psychological theories that relate shifting attitudes about the family to such factors as capitalist ideology (Shorter 1975), economic insecurity (Ruggles 1987), or affluence (Lesthaeghe and Meekers 1986).8

Family norms have shifted dramatically since the mid-nineteenth century. Nineteenth-century writings on the family—whether prescriptive literature, letters, diaries, or even sentimental novels—are filled with admonitions about the duties and obligations of family members (Houghton 1957; Norling 2000; Ruggles 1987). Changing attitudes increased the freedom of the younger generation to leave home, reinforcing the decline of intergenerational coresidence. It is difficult, however, to disentangle the web of material conditions, residential behavior, and attitudinal change. The decline of household production probably contributed to the weakening of bonds of obligation (Mason 1992). Family norms also probably altered in response to changes in residential behavior; as more and more elders lived alone, the authority of the older generation became more diff icult to sustain (Goldscheider and Lawton 1998). It may be fruitless to attempt to distinguish an independent effect of attitudinal change on family composition: material conditions, family behavior, and attitudes were changing simultaneously, and it is likely that the changes were mutually reinforcing.

DATA AND STRATEGIES

This investigation evaluates evidence bearing on two major hypotheses for the decline of intergenerational coresidence: the affluence hypothesis and the economic development hypothesis. As noted above, the affluence hypothesis—the consensus view of social scientists in recent decades—posits that rising economic resources of the aged increasingly allowed them to maintain independent residences. The economic development hypothesis—embraced by earlier generations of theorists and policymakers—contends that rising wage-labor opportunities and the declining importance of agricultural inheritance reduced the incentives for members of the younger generation to remain in their parents’ homes.

The analysis relies on the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS), a collection of high-precision census microdata samples spanning the period from 1850 through 2000 (Ruggles et al. 2004). IPUMS samples for 1850 through 1950 were created by entering information from microfilm copies of handwritten census enumerators’ manuscripts. For 1960 through 2000, IPUMS relies on machine-readable, public-use microdata created by the Census Bureau following each enumeration. All IPUMS samples are coded into a uniform system, and the data series provides comprehensive documentation of comparability issues. Despite various changes in the definitions of households and families over the past 150 years, used with appropriate care IPUMS data can provide highly compatible estimates of changes in intergenerational living arrangements (Ruggles and Brower 2003).

I use five analytic strategies to assess the affluence and economic development hypotheses. First, I examine trends in headship patterns of intergenerational households to obtain insight into patterns of household formation, a key component of theories of family change. Second, I assess long-run changes in the relationship of occupation to intergenerational coresidence for both the younger generation, defined as men ages 30 to 39, and the older generation, defined as men age 65 or older. Third, I turn to data on income available in the census since 1950 and compare the effect of income on coresidence for the younger and older generations. Fourth, I use measures of income and education for both generations simultaneously in a pooled fixed-effects spatial model of the relationship of socioeconomic status to coresidence. Finally, I employ a counterfactual approach to develop an upper-bound estimate of the impact of Social Security benefits on the living arrangements of the aged.

EVIDENCE ON HEADSHIP

Headship patterns help us evaluate who moved in with whom. As Choi (2003:395) demonstrates, who moves in with whom is a strong indicator of which generation is the beneficiary of intergenerational living arrangements. According to the affluence hypothesis, nineteenth-century elders moved in with their children when they became too impoverished or infirm to maintain their own homes. According to the economic development hypothesis, nineteenth-century children remained in their parental homes after reaching adulthood to provide labor and eventually inherit the farm or business.

Information in the census on headship status offers insights into intergenerational household formation. From 1850 to 1870, the Census Office instructed enumerators to list the head of each family first, and from 1880 to 1970, the census explicitly identified the head of each family or household. Headship was never defined by the census; under the patriarchal family system of the nineteenth century, it was simply assumed that every household had a head and that there was never ambiguity about which household member filled that role. By 1980, the concept of household head was anachronistic, and it was replaced by the concept of “householder.” Any person listed on the household’s lease or mortgage could be designated the householder; if no such person was present, any adult could be selected (Ruggles and Brower 2003; Shammas 2002; Smith 1992).

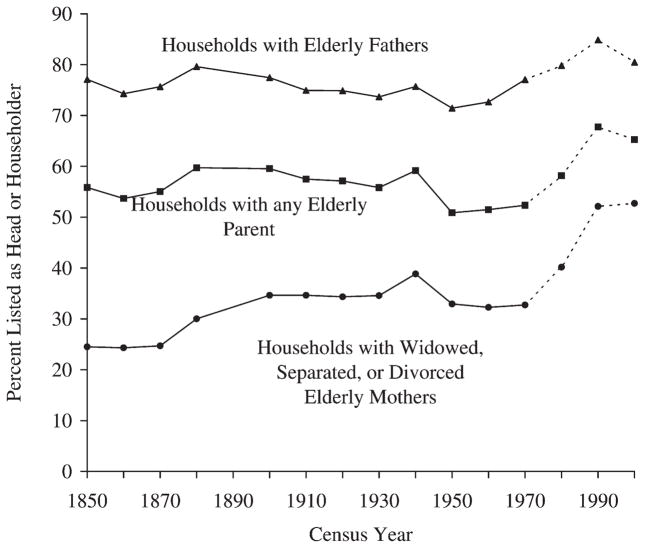

Figure 3 shows the percentage of intergenerational families in which the older generation was listed as family head, household head, or householder in each census year since 1850. Intergenerational families are here defined as families containing a person age 65 or older residing with his or her own child age 18 or older. In families that include an elderly father (top line), headship has always been overwhelmingly vested in the older generation. This pattern is inconsistent with the hypothesis that elderly men typically moved in with their children because they could no longer support themselves; it is hard to imagine that an infirm or destitute elderly father taken into a child’s home as an act of charity would assume the household headship. It is far more plausible that the younger generation simply remained in the parental household after reaching adulthood, or that they returned to their parental homes after a period of independence.

Figure 3.

Percent of Intergenerational Households in which the Older Generation is Head or Householder: United States Households with Persons Age 65+ Residing with Own Children, 1850 to 2000

Source: Ruggles et al. 2004.

When we consider all intergenerational families (middle line), the percentage of heads in the older generation is lower, although it still represents a majority in all census years. Among households in which the only surviving parent was a widowed, separated, or divorced mother (lower line), her son or son-in-law was typically listed as the head before the late twentieth century. That does not mean, however, that the mothers usually moved in with their children for support. In the nineteenth century, the great majority of such women were already living with their children before they became widowed.9 When the patriarch died, the bulk of the property—and the headship of the household—passed directly to his son or son-in-law (Ruggles 2003; Shammas, Salmon, and Dahlin 1987).

The affluence hypothesis contends that intergenerational coresidence came about when dependent elderly parents moved in with their children. In fact, this pattern has always represented a minority of intergenerational living arrangements. The evidence on headship suggests that in all periods the majority of elders who resided with children remained in their own homes; it was the younger generation who either moved in with parents or who never left home. Thus, it was not the older generation that shifted its behavior between 1850 and 2000 as much as it was the younger generation.

EVIDENCE ON OCCUPATIONS

The census allows us to investigate the sensitivity of intergenerational coresidence to the economic resources of each generation. The only measure of economic status consistently available over the past 150 years is occupation. To assess the relationship of nonfarm occupations to intergenerational coresidence, I divide job titles into three broad groupings based on the 1950 U.S. Census occupational classification. High-status workers—professionals, technical workers, managers, officials, and proprietors—rose from 9.2 percent of the workforce in 1850 to a peak of 33.6 percent in 1980. The mid-status workers include the broad categories of clerical, sales, crafts, services, and operatives; they represented 29.8 percent of the workforce in 1850 and rose to a peak of 60 percent in 1970. Finally, the low-status occupations consist of laborers, who reached a peak of 22.7 percent of the workforce in 1870 and slowly declined thereafter.

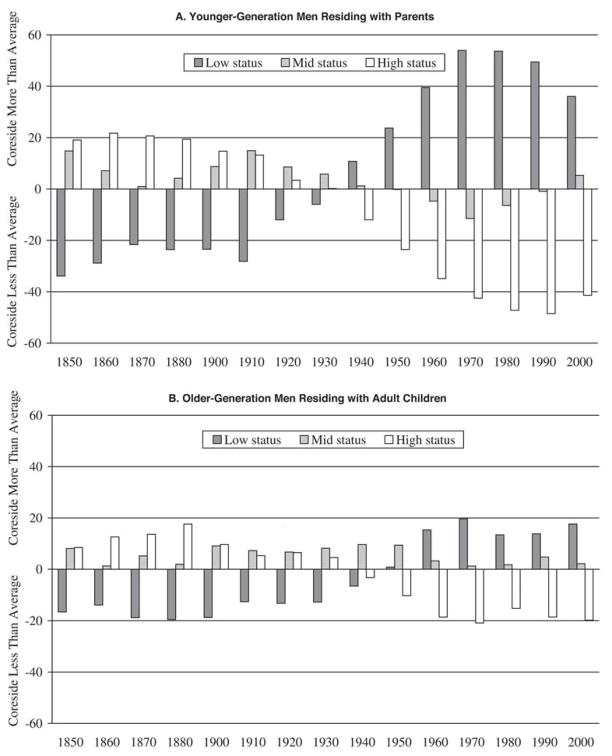

Figure 4 presents the relationship between intergenerational coresidence and the three occupational categories. I compare two generations of men; women are excluded because occupation is a poor indicator of socioeconomic status for most women in most of the period under consideration. The younger generation is defined as men ages 30 to 39, and the older generation consists of men age 65 or older. I define the younger generation as 30 to 39 because those ages are beyond the usual ages of leaving home (Gutmann, Pullum-Piñón, and Pullum 2002) and yet are young enough that even in the nineteenth century about half still had a surviving parent with whom they could potentially reside (Ruggles 1994).10

Figure 4.

Percent Deviation in Intergenerational Coresidence of Each Occupational Group from Nonfarm Average: U.S. Men, 1850 to 2000

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

The frequency of intergenerational coresidence varied substantially over time and between generations, complicating the analysis of trends and differentials in the occupational pattern of coresidence. Accordingly, the statistics in Figure 4 are expressed in a uniform scale of measurement: the percent deviation in intergenerational coresidence of each occupational group from the average of all groups. Thus, for example, the leftmost set of bars in Panel A of Figure 4 shows that in 1850, younger-generation, low-status workers resided with parents 34 percent less often than average; high-status workers, how- ever, resided with parents 19 percent more often than average.

Panel A also shows that from 1850 through 1910, while high-status workers were far more likely to reside with parents than were low-status workers, the strength of that relationship diminished over time. In 1940, the relationship between occupational status and residence with parents reversed. By 1970, low-status workers were 54 percent more likely than average to reside with parents, and high-status workers were 43 percent less likely than average to core-side. After 1980, the magnitude of the inverse relationship between occupational status and intergenerational coresidence diminished somewhat, but it remained highly significant.

What accounts for the reversal in the relationship between socioeconomic status and coresidence between the mid-nineteenth and late-twentieth centuries? According to the affluence hypothesis, the nineteenth-century pattern makes sense: members of the younger generation with the greatest resources would be in the best position to take in their infirm and destitute parents. This theory cannot, however, account for the concentration of coresidence among younger-generation men in the lowest-paid jobs after 1920.

The economic development hypothesis offers a more plausible explanation that fits both the nineteenth- and the twentieth-century pattern. In the nineteenth century, the bulk of the men in high-status occupations were proprietors of one sort or another. Many of these people inherited their businesses from their fathers. To a lesser extent, that was true in the mid-status jobs as well; among the common titles in that category were bakers, brickmasons, cabinetmakers, carpenters, and shoemakers, who typically had their own workshops. Many craftsmen inherited their occupations from their fathers, and a son who lived with his parents was no doubt more likely to inherit. Sales clerks had an especially high rate of coresidence in the nineteenth century; many of them probably worked in their fathers’ stores, with the expectation of eventual inheritance. In the twentieth century, the high-status and mid-status occupational categories were increasingly dominated by wage and salary jobs—such as managers and factory workers—that rarely depended on occupational inheritance. As household-based production disappeared, so did the incentives to remain at home. In this environment, the sons with the most resources were the ones most likely to establish independent residence.

Occupational analysis is less useful when we turn to the older generation. Occupational data is available for 85 percent of nineteenth-century men age 65 or older, but for less than half of those enumerated from 1950 onward. Therefore, occupational statistics for elders in recent census years could be unrepresentative. Panel B of Figure 4 shows the percent deviation in residence with an adult child for each occupational category. In general, the relationships between occupation and coresidence are similar for the older and younger generations, but they are attenuated for the older generation. The greater sensitivity of intergenerational coresidence to the status of the younger generation than to that of the older generation supports the economic development hypothesis that rising wage-labor opportunities reduced the incentives for the younger generation to remain in their parental homes.

Figure 4 does not include farmers. The shift from farming to wage labor was already well underway in 1850, and it was considerably more advanced among the younger generation (41.7 percent farming) than among their elders (62.3 percent farming). By 2000, farming had ceased to be a significant occupation, accounting for less than 2 percent of the workforce in either generation. As predicted by the economic development hypothesis, in every census year younger-generation men engaged in farming were the occupational group most likely to reside with parents. In the nineteenth century, younger-generation men in farming were, on average, 91 percent more likely to reside with parents than were nonfarmers, and in the twentieth century they were 60 percent more likely to do so. Older-generation farmers were also generally more likely to reside with children than were elderly men with other occupational titles, but the effect was smaller and disappeared entirely after 1970.

The reversal in the relationship between occupational status and intergenerational coresidence suggests a likely explanation for the racial crossover illustrated in Figure 1. In the late nineteenth century, blacks were less likely than whites to reside in intergenerational families, and in the late twentieth century they were more likely to do so—a reversal previously identified by Ruggles and Goeken (1992), Kramarow (1995), and Goldscheider and Bures (2003). This shift makes sense in light of the occupational analysis presented here. Newly-freed blacks in the late nineteenth century had few resources. Although most blacks were listed in the census as farmers, they were usually sharecroppers or tenant farmers and had no agricultural inheritance to offer their children.11 Like others with few resources, they had comparatively few intergenerational families. In the late twentieth century, blacks remained at the bottom of the economic ladder, but by that time those with fewest resources were the group most likely to coreside with elderly parents.

EVIDENCE ON INCOME

The growth of the Social Security program and private pension plans in the twentieth century meant that more and more elders had secure cash incomes, even though fewer and fewer had their own farms or businesses. According to the affluence hypothesis, this meant the aged increasingly had the economic means to maintain separate residences. For the recent period, unlike the nineteenth century, this hypothesis has some plausibility. As noted above, until the mid-twentieth century those with the highest economic status were the most likely to form intergenerational families. From 1850 through 1940, it is therefore unlikely that an increase in the economic resources of the aged would have led to an increase in the percentage living alone. In the second half of the twentieth century, however, the pattern reversed: elders with the greatest resources were the ones most likely to live independently. Since 1950, it makes sense that the rising income of the aged contributed to the decline of intergenerational coresidence.

Many investigators have estimated the impact of rising income on living arrangements of the aged in the late twentieth century using regression or decomposition methods. The results vary, but most analysts suggest that rising income might account for between 15 and 50 percent of the change (Macunovich et al. 1995; McGarry and Schoeni 2000; Michael et al. 1980; Pampel 1983; Ruggles and Goeken 1992). A few analyses have found that increasing the income of the aged does not raise their probability of living alone (Börsch-Supan et al. 1992; Schwartz, Danziger, and Smolensky 1984). Much of the variation among investigators is attributable to variation in the particular population under study, the measure of family structure employed, or the time period examined. 12

None of these studies control for a critical intervening variable: the income of the younger generation. Suppose low-income elders tend to have low-income children, and low-income children often reside with their parents because they cannot afford to live alone. Under these circumstances, the observed inverse relationship between income and coresidence of the aged could be partly an artifact of the economic circumstances of the younger generation. We lack historical data on the incomes of noncoresident children of the aged that would allow us to test this directly. We can, however, compare the relationship of income to coresidence in the older and younger generations.

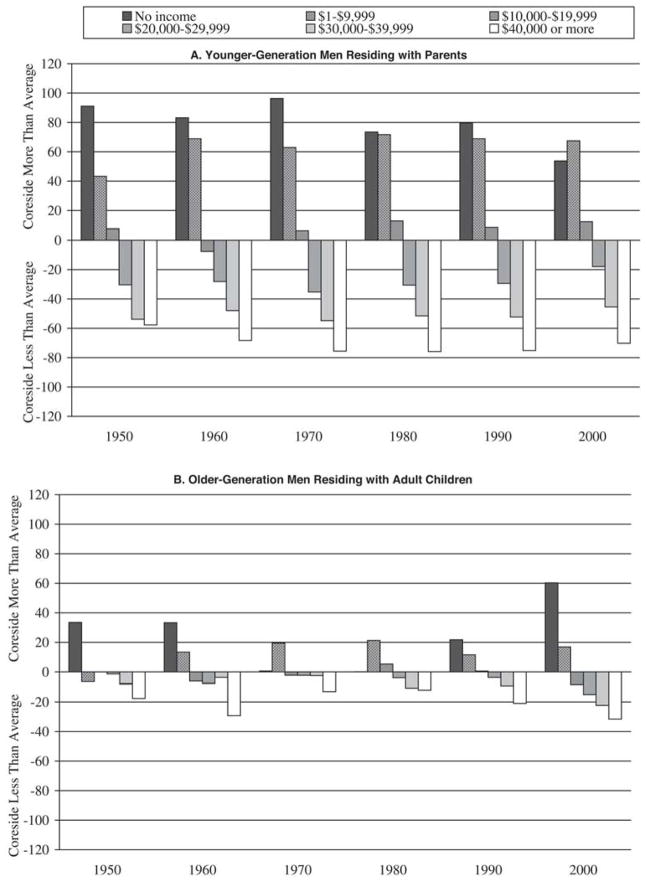

Figure 5 is similar to Figure 4, but it is based on income groups instead of occupational groups. The bars represent the percent deviation in intergenerational coresidence of each income group from the overall average of all income groups. As in Figure 4, the upper panel displays the results for the younger generation, and the lower panel focuses on the older generation.

Figure 5.

Percent Deviation in Intergenerational Coresidence of Each Income Group from Overall Average: U.S. Men, 1950 to 2000

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

For younger-generation men, coresidence was highly sensitive to income. From 1950 through 1990, younger-generation men with no income were 74 to 96 percent more likely than average to reside with parents. With each successive increase of income, the likelihood of coresidence diminished. In the highest income group—those with over $40,000 of income in 2000 dollars—younger-generation men were 58 to 76 percent less likely than average to core-side. Panel B of Figure 5 shows the comparable statistics for older-generation men. The effect of income on coresidence for the older generation is significant, but it is modest when compared with the effects for the younger generation. In all census years, the inverse association between income and coresidence was far stronger for the younger generation than for the older generation.

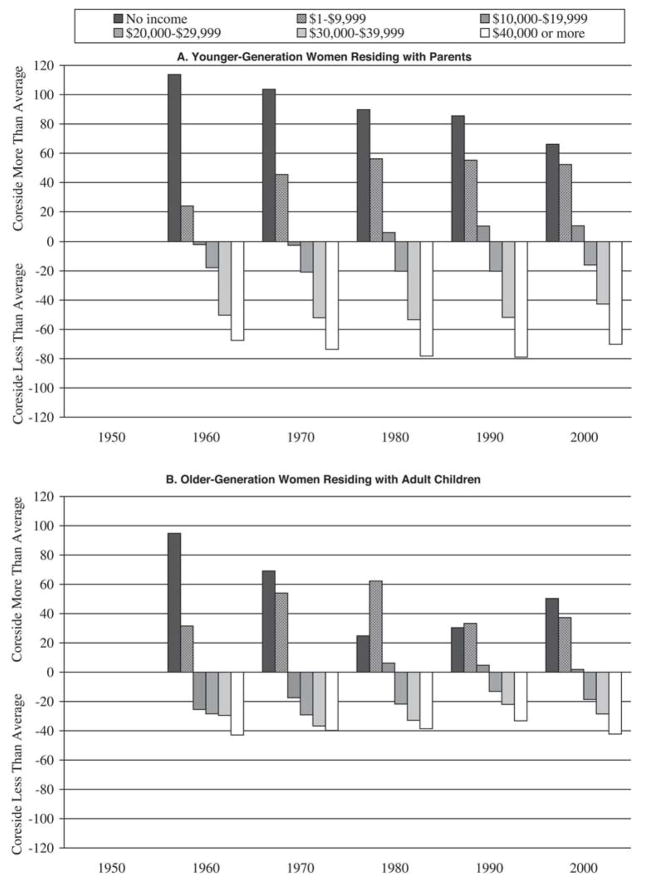

Individual income is an unsatisfactory measure of socioeconomic status for many women, especially in the mid-twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, women often dropped out of the labor force upon marriage and relied on their husband’s earnings; in 1950, 84 percent of married women in their thirties had less than $1,000 of income. Moreover, the issue is not confined to the younger generation; aged married women frequently had little or no individual income, since pensions and Social Security benefits were in their husbands’ names. To mitigate these problems, I substitute the income of husbands when available. This analysis is confined to the period from 1960 onward, since that is the period in which we have income data for spouses.13 The results, shown in Figure 6, suggest that coresidence was even more sensitive to income among women than among men. The pronounced inverse relationship between income and coresidence is apparent for both generations of women. The difference between generations, however, appears less marked among women than among men.

Figure 6.

Percent Deviation in Intergenerational Coresidence of Each Income Group from Overall Average: U.S. Women, 1950 to 2000

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

Despite variations in magnitude, the generational comparisons in Figures 4 through 6 all indicate that during the second half of the twentieth century, living arrangements of the young were more sensitive to variation in socioeconomic status than were living arrangements of the old. This suggests that the association of low income and intergenerational coresidence among the aged could be at least in part a byproduct of the behavior of their children. That is, low-income elders may reside with their children more often than those with high income mainly because low-income elders tend to have low-income children. Without individual-level historical data linking the income of the aged to that of non-coresident offspring, it is challenging to test this hypothesis directly. We can, however, examine the issue through spatial analysis.

SPATIAL ANALYSIS

The postwar boom in well-paid wage labor jobs did not occur evenly across the country. The combination of great spatial variation and rapid chronological change in the economy allows us to assess the association between the decline of intergenerational coresidence and the rise of good wage-labor jobs for the younger generation. Spatial analysis allows us to examine the historical relationship of economic opportunity to intergenerational coresidence for both generations simultaneously, which is impossible with existing individual-level data.

To evaluate the effects of changing income and education on the living arrangements of the aged between 1950 and 2000, I turn to state-level spatial models. Table 1 describes the variables included in the analysis. The dependent variable is the percentage of persons age 65 or older residing with an adult child. There are two income measures: the percentage of elderly persons in the state with low incomes, and the percentage of the younger generation—again defined as those ages 30 to 39—with low incomes. Low income is defined as one-half the national median income for each age group in 2000. To evaluate the impact of education, the analysis includes the percentage of each generation with 12 or more years of schooling. State effects are controlled to account for unobserved state differences in residential behavior that persist over time.

Table 1.

State-Level Measures of Intergenerational Coresidence, Earnings, and Education, 1950 to 2000

| 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | All Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean of States: | |||||||

| Percent age 65+ residing with their children | 34.1 | 24.4 | 17.4 | 13.9 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 19.6 |

| Percent age 30 to 39 with low incomes | 55.8 | 44.8 | 39.0 | 32.3 | 29.7 | 28.5 | 38.7 |

| Percent age 65+ with low incomes | 75.4 | 61.6 | 49.1 | 32.1 | 27.5 | 23.7 | 44.9 |

| Percent age 30 to 39 completed high school | 44.0 | 54.6 | 66.7 | 81.9 | 89.3 | 89.8 | 71.1 |

| Percent age 65+ completed high school | 17.1 | 19.3 | 27.0 | 38.8 | 56.5 | 69.2 | 38.0 |

| Standard Deviation: | |||||||

| Percent age 65+ residing with their children | 6.6 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 8.9 |

| Percent age 30 to 39 with low incomes | 7.1 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 11.0 |

| Percent age 65+ with low incomes | 6.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 20.0 |

| Percent age 30 to 39 completed high school | 10.9 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 18.9 |

| Percent age 65+ completed high school | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 20.5 |

| Number of Cases: | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 276 |

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

Notes: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Nevada, and Wyoming are excluded because of insufficient cases; the District of Colombia is treated as a state. Low income is defined as half the median income for each age group in the 2000 census (under $12,046 for persons ages 30 to 39, and under $6,998 for persons age 65 or over in 2000 dollars).

Table 2 presents six models. Models 1, 3, and 5 are Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions. Test statistics reveal the presence of spatial autocorrelation. To control for omitted spatially correlated covariates, I also provide three Spatial Autoregressive (SAR) models (2, 4, and 6).14 The differences between the OLS and SAR models are not substantively important, lending confidence to the robustness of the results. Models 1 and 2 show the overall change in the percentage of elders residing with children, without controlling for income or education. The models show declines of 19.6 and 19.4 percentage points in residence of elders with children between 1950 and 2000. Models 3 and 4 add the variables describing the percentage of each generation with low incomes. The coefficients for both income measures are significant: as expected, low income is positively associated with coresidence. In both Model 3 and Model 4, however, the effect is significantly stronger for the younger generation than for the older generation.15 Once the percent low-income is controlled, there is no significant difference between the percentage of elders coresiding with children in 2000 and the percentage doing so in 1950 or 1960.

Table 2.

State-Level Models of Education and Income on Percent of Elders Residing with Adult Children: Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Spatial Autoregressive (SAR) Models with Pooled Data, 1950 to 2000

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS |

SAR |

OLS |

SAR |

OLS |

SAR |

|||||||

| B | t | B | z | B | t | B | z | B | t | B | z | |

| Census Year | ||||||||||||

| 1950 | 19.61 | 36.00*** | 19.35 | 24.08*** | 4.29 | 1.64 | 5.79 | 2.11* | .97 | .25 | .72 | .21 |

| 1960 | 9.87 | 18.13*** | 9.56 | 11.89*** | −.34 | −.15 | .14 | .07 | −3.99 | −1.22 | −4.14 | −1.39 |

| 1970 | 2.91 | 5.34*** | 2.74 | 3.41*** | −3.41 | −2.26* | −3.14 | −2.20* | −5.88 | −2.30* | −5.95 | −2.57** |

| 1980 | −.61 | −1.11 | −.60 | −.74 | −2.79 | −4.07*** | −2.61 | −3.30*** | −3.42 | −2.12* | −3.37 | −2.29* |

| 1990 | −1.03 | −1.89 | −.98 | −1.23 | −1.87 | −3.48** | −1.78 | −2.54* | −1.14 | −1.58 | −1.17 | −1.71 |

| 2000 | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) | ||||||

| Income and Education | ||||||||||||

| Percent age 30 to 39 with low incomes | .30 | 6.42*** | .25 | 5.35*** | .12 | 2.85*** | .13 | 3.13*** | ||||

| Percent age 65+ with low incomes | .12 | 2.31* | .14 | 2.78* | −.01 | −.30 | .01 | .19 | ||||

| Percent age 30 to 39 completing high school | −.37 | −8.60*** | −.35 | −8.70*** | ||||||||

| Percent age 65+ completing high school | .01 | .30 | .02 | .39 | ||||||||

| State Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Constant | 14.42 | 1.12 | 14.53 | 12.77*** | 4.29 | 2.59 | 5.56 | 3.16 | 43.84 | 6.77*** | 42.07 | 6.25*** |

| rho/lamda | .47 | 7.99*** | .40 | 6.41*** | .15 | 2.02*** | ||||||

| Adjusted R Square/Pseudo F | .91 | .82 | .93 | .86 | 0.95 | .94 | ||||||

| Log Likelihood | −600 | −582 | −546 | |||||||||

| N | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 | 276 | ||||||

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

Note: Omitted state is New Hampshire.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001 (two-tailed tests).

Models 5 and 6 add the educational variables: the percentage each generation with 12 or more years of schooling. The coefficients for both income and education in these models are insignificant for the older generation, but they are highly significant for the younger generation. Moreover, the coefficients for the census years are all negative or insignificant in Models 5 and 6, suggesting that the rising income and education of the younger generation could be responsible for the decline in coresidence among the aged between 1950 and 2000. By contrast, the usual explanation for the change—the rise in income of the aged themselves—does not appear to have an independent relationship to living arrangements. Indeed, the insignificant coefficients for income and education of the older generation suggest that the inverse association between income and coresidence of the aged, observed in the individual-level analysis, could simply be a byproduct of the much stronger relationship observed for the younger generation.16

THE EFFECTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY

In recent years, several analysts have argued that Social Security and other old-age assistance programs are key factors behind the extraordinary historical changes in the living arrangements of the aged (Costa 1997, 1999; Engelhardt et al. 2002; McGarry and Schoeni 2000). These studies use aggregate-level measures of Social Security income. For example, McGarry and Schoeni (2000) impute an average Social Security benefit to each widowed woman in the IPUMS samples for 1940 through 1990. In 1940, only one in a hundred widows actually received a Social Security benefit, but they nevertheless assign an average benefit to every widowed woman in the population. This imputed average benefit works out to about $1.86 per woman in 1940 (in 1990 dollars) and rises dramatically to $530 per woman in 1990—an increase of almost 300-fold.17 During the same 50-year period, residence with adult children fell from 58.7 percent to 19.5 percent. It is no surprise that when McGarry and Schoeni enter the average imputed benefit as an independent variable in a pooled logistic regression analysis of intergenerational coresidence, they find that for every $100 of additional Social Security benefits, coresidence with adult children falls about 6 percent. They conclude that Social Security increases “explain” 47 percent of the change in coresidence (p. 233). This inference of causality is unwarranted; the model simply reflects the fact that Social Security benefits were rising as coresidence declined and does not establish a causal link between the two changes.18

Actual Social Security benefits have been included in the census since 1970, and it is possible to use them to estimate the maximum potential impact of the program through a simple counterfactual strategy. The calculation requires two assumptions. First, we assume that the non-Social Security income of the aged has not been affected by the existence of the program (e.g., that Social Security did not discourage private pensions and savings). This assumption allows us to calculate what the income distribution of the elderly population would be if there were no Social Security program: for each individual or married couple, we simply subtract Social Security income from total income. For example, if we count Social Security income, only 4 percent of elderly individuals or couples in 2000 had income under $2,500; without Social Security, 25 percent would have fallen in the under-$2,500 category.

The second assumption is that the observed inverse relationship between income and coresidence is explained by the affluence hypothesis and is not simply a byproduct of the correlated income of the younger generation. If the only reason low-income elderly people tend to live with their children is because they cannot afford to live on their own, we can estimate the impact of income on living arrangements.

Given these assumptions, we can calculate the percentage of coresidence in the absence of Social Security as

where Ci is the observed percentage of elders residing with adult children at each income i, and pi is the proportion of elders who would have been in that income group were it not for Social Security.

The impact of weighting the data in this fashion is shown in Figure 7. The results suggest that in the absence of Social Security, the percentage of elders residing with adult children potentially could rise as much as 4.0 to 5.9 percentage points, depending on the census year.19 These are certainly overestimates, however, because both our assumptions exaggerate the impact of Social Security. In reality, we know that at least some of the observed relationship between income and coresidence of the aged must result from the correlated income of their children. Moreover, private savings and pensions would be somewhat larger if Social Security did not exist. Thus, the calculation yields an upper-bound estimate of the impact of Social Security. That upper bound, however, is very low: the Social Security program can account for less than 13 percent of the decline in intergenerational coresidence since the introduction of the program in 1936 and under 8 percent of the total decline in coresidence over the past 150 years. Analyses that report substantially greater effects of Social Security are not credible. Social Security is the largest social program ever undertaken in the United States. A substantial body of literature suggests that living arrangements of the aged are highly sensitive to Social Security benefit levels. Compared with the extraordinary changes in the family over the last 150 years, however, the potential effects of Social Security are small.

Figure 7.

Percent of Elderly Residing with Children, Showing Potential Effects of Removing Social Security Income: United States Individuals and Couples age 65+, 1850 to 2000

Source: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 3.0 (Ruggles et al. 2004).

Note: See text for explanation of method.

If Social Security is not the primary cause of the revolution in living arrangements, however, it may be partly a consequence of family changes. The creators of the Social Security program believed that the need for old-age assistance had greatly increased because of the rise of wage labor, the decline of farming, and the resulting change in the living arrangements of the aged. Earlier in this article, I quoted Thomas H. Eliot, who explained that old-age assistance was needed because the younger generation was leaving parental farms to go work in the city. Another drafter of the original Social Security legislation, J. Douglas Brown, wrote of the problems created when “older people had been left behind as young people moved to the cities” (Brown 1972:6). Ewan Clague, who joined the Social Security Board in 1936, wrote that earlier in the century, “old people simply lived on the farm until they died … consequently, the modern old-age problem hadn’t developed” (Clague 1961). In 1937, the constitutionality of Social Security was challenged. Writing for the majority that upheld the program, Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo noted, “Congress did not improvise a judgment when it found that the award of old age benefits would be conducive to the general welfare.” The bill was backed by “an extensive mass of facts” uncovered by an administration committee, congressional hearings, and seven advisory groups. Chief among these facts was the finding that “the number of [persons age 65 or older] unable to take care of themselves is growing at a threatening pace. More and more our population is becoming urban and industrial instead of rural and agricultural” (Helvering v Davis, 301 U.S. 619 [1937]).

The Social Security program was thus justified and defended on the grounds that economic changes had left many elders without coresident family. The history of Social Security legislation is complex and contested, and there are many reasons—both officially acknowledged and unacknowledged—why the program was adopted (e.g., Dahlin 1993; Lubove 1968; Quadagno 1984; Tynes 1996). There can be little doubt, however, that the designers of the Social Security system saw it—at least in part—as a response to changes in the family that had already taken place because of the decline of farming and the rise of wage labor.

DISCUSSION

According to the consensus of recent scholarly opinion, the simplification of the living arrangements of elderly people during the twentieth century resulted primarily from an increase in their resources, which enabled increasing numbers to afford independent living. Analysis of the historical evidence suggests instead that the decline of the multigenerational family occurred in large measure because of increasing opportunities for the young and declining parental control over children.

The decline of intergenerational coresidence made sense for both the older and younger generations. With the transformation of the economy, the older generation no longer needed the labor their sons and daughters once provided, and the aged could no longer offer the younger generation employment and inheritance of the family farm or business. The process occurred in stages. First, many young people left their parents for the excitement, independence, and high wages of the towns and cities. Then, when these life-long wage earners grew old, they had no farm or business for the next generation to inherit; their own children had little incentive to remain at home, and the older cohort had little reason to want them to stay.

The affluence hypothesis postulates that elders always preferred to reside independently, but they moved in with their children when they became impoverished or infirm. I have shown elsewhere that neither poverty nor infirmity was associated with coresidence of the aged in the nineteenth century (Ruggles 2003). Data presented here on household headship reinforces these findings. For the past 150 years, only a minority of intergenerational households were formed when elderly parents moved in with children; in most cases, the older generation remained in their own homes.

Before 1930, intergenerational coresidence was highest in families with either a farm or a business for the younger generation to inherit, and in that period, those were the highest-status families. By the middle of the twentieth century, however, most high-status workers were no longer proprietors, but instead worked for a salary. As a result, the positive association between socioeconomic status and intergenerational coresidence reversed. By 1950, there was a powerful inverse relationship between the economic resources of the younger generation and the likelihood of residence with parents. An inverse relationship between economic status and coresidence also emerged among the older generation, but it was substantially weaker. In all periods, intergenerational cores-idence apparently depended more on the occupation or income of the younger generation than on the economic status of the aged.

Spatial analysis of the relationship of living arrangements to the economic opportunities of each generation reinforces this conclusion. The analysis reveals a powerful geographic association between low opportunity for the younger generation and high intergenerational coresidence; this relationship is strong enough to account for the entire decline in coresidence between 1950 and 2000. By contrast, once we control for the income and education of the younger generation, there is no spatial relationship whatsoever between the socioeconomic status of elders and intergenerational coresidence. Taken together with the individual-level analyses of income and occupation, these results provide compelling evidence that the decline of intergenerational coresidence had less to do with the growing affluence of the aged than with the increasing opportunities for the younger generation.

The rising income of elders did have some effect on their living arrangements. In all periods, some elderly persons resided with their children because they needed assistance with health conditions or economic support. The increasing economic independence of the aged—brought about in part by the Social Security program—contributed to the increase of separate residences and helped to accelerate the pace of decline in coresidence in the years following World War II. Rising affluence of the aged was not, however, the primary reason for the massive decline in intergenerational coresidence since 1850; the increasing resources of the younger generation played a much more important role. Moreover, even in the second half of the twentieth century, the Social Security program can plausibly account for only a small fraction of the change in family structure.

Despite a substantial increase in the cash income of the aged in the last 150 years, patriarchal authority has greatly diminished.20 The mid-nineteenth-century family was organized according to patriarchal tradition (Mintz and Kellog 1988; Rosenfeld 2006; Shammas 2002). The master of the household had a legal right to command the obedience of his wife and children and to use corporal punishment to correct insubordination (Siegel 1996:2122–23). In most states, husbands owned the value of their wives’ labor, as well as most property women brought into marriage (Shammas et al. 1987; Siegel 1996). The internal dynamics of the American family shifted radically during the next 150 years. Beating children is now frowned upon and restricted, wife beating is illegal, and in most families husband and wife share property and decision making. Patriarchal authority has diminished to the point that the very concept of “Household Head” is obsolete; as noted earlier, the Census Bureau abandoned the term in 1980 to avoid offending the public. The decline in paternal authority over adult children makes sense in light of the shift of economic power within the family. When young men could obtain well-paid employment for wages, they no longer had much incentive to remain at home under the control of their fathers. Once the fathers no longer controlled agricultural inheritance, there was even less reason for the sons to obey.

The transformation of the power structure of the family encompassed gender relationships as well as generational relationships, and the change in gender relationships also depended on shifting economic control. In the agricultural world of the early nineteenth century, most women spent their lives on farms controlled by their fathers, husbands, and sons (Shammas et al. 1987). They had few available alternatives. Women had always worked, and in all periods they played a vital economic role in family businesses and in the larger economy (Abel and Folbre 1990; Bose 1987). Starting in the late nineteenth century, opportunities grew for women to work outside the confines of the family economy and outside of the control of husbands and fathers. Wherever wage-labor opportunities for women appeared, they provided the means to live independently and to escape from abusive marriages. From 1880 onward, there was a consistent and close geographic association between the opening of female wage-labor opportunities and the rise of divorce and separation (Ruggles 1997). Even for women who remained in their families and did not work for wages, the growth of job opportunities magnified their bargaining power with husbands and fathers.

The decline of intergenerational coresidence and the rise of marital instability probably would not have occurred without changes to nineteenth-century patriarchal family norms. Such norms did not immediately disappear with the rise of wage labor. The nineteenth-century family was a potent social construct, and the authority of the patriarch diminished gradually. The timing of changes in intergenerational coresidence suggests that many families stayed together after the economic incentives for intergenerational coresidence had disappeared. Comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2 reveals a distinct lag between the decline of farming and the decline of intergenerational families. By 1920, only 22 percent of younger-generation men remained in farming. The economy was no longer based on household production. The aged no longer had a compelling reason to keep adult children at home, and the younger generation no longer had much incentive to stay. Still, almost half of elders in 1920 continued to reside with their adult children.

Residence with parents was a powerful norm, and it was not immediately abandoned by every young person who obtained a decent wage-labor job. Rather, without the economic incentives to both generations provided by the traditional family economy, patriarchal authority and norms favoring coresidence gradually eroded. The evidence indicates that rising economic opportunities for the younger generation can account for most of the long-term decline of intergenerational coresidence. The lag between occupational change and family change, however, suggests that cultural inertia operated as a brake on changes in family behavior, keeping generations together even after the material basis for coresidence had vanished.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and preparation was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD043392 and other grants) and the National Science Foundation (SBR-9617820 and other grants).

Biography

Steven Ruggles is Distinguished McKnight University Professor of History and Director of the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota. He is Principal Investigator of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) projects, and has received the William J. Goode Award from the Family Section of the American Sociological Association, the Allen Sharlin Award from the Social Science History Association, and the Robert J. Lapham Award from the Population Association of America. His current research interests include family demography, the history of American living arrangements since 1850, international comparative analysis of family patterns, and development of historical population data.

Footnotes

The census did not record family composition for slaves, so information on the black population begins after emancipation.

For example, see Smith (1986), Costa (1997), Elman (1998), McGarry and Schoeni (2000), Kramarow (1995), Wall (1995), Hammel (1995), Schoeni (1998), Gratton (1986:60), Haber and Gratton (1994:45–47). The idea that extended families were a refuge for the poor in the nineteenth century was also widespread in the work of the first generation of quantitative social historians (see Ruggles 1987:26–27).

The idea that intergenerational coresidence was only resorted to in cases of dire necessity can be traced to Laslett’s (1965 Laslett’s (1972) finding four decades ago that preindustrial English households were rarely extended. In fact, however, the percentage of households containing extended kin does not predict the living arrangements of elders. Long generations, short life expectancy, and high fertility before the demographic transition meant that there was a small population of elderly people spread thinly among a much larger younger generation, and the percentage of households incorporating elderly kin was necessarily small (see Ruggles 1987, 1993, 1994, 1996a, 2003).

McGarry and Schoeni (2000) challenged the finding of Ruggles (1996b) and Ruggles and Goeken (1992) that intergenerational coresidence was positively associated with affluence in the nineteenth century, arguing that occupation is a poor indicator of socioeconomic status. Other indicators, however—such as real and personal property, value of dwellings, and presence of domestic servants—also support this association (Ruggles 1987, 2003). Using indirect indicators from 1940 to 1950 McGarry and Schoeni find no positive association, but as discussed below, I am not persuaded by their method. Moreover, I argue that the positive association between affluence and coresidence disappeared by the mid-twentieth century, so McGarry and Schoeni’s evidence about the 1940 to 1950 period is not germane.

Mid-twentieth-century sociological literature highlighted the connection between industrialization and nuclear family structure (e.g., Parsons 1949) and the theory of a transition from stem families to conjugal families was a standard feature of leading sociology textbooks (e.g., Ogburn and Nimkoff 1950:469–73). In the early 1960s, however, the theory came under increasing criticism (e.g., Goode 1963; Greenfield 1961; Litwak 1965; Shanas 1961; Sussman 1959). Once Laslett (1965) announced that family structure had remained unchanged in England for three centuries, Le Play’s formulation fell from favor. For contrasting interpretations of the history of these ideas, compare Ruggles (1994) and Smith (1993).

Most of these models control for agricultural employment or farm residence; farming is highly correlated with intergenerational coresidence, and there are few farms in urban areas.

The minimal impact of fertility decline is largely because there was little relationship of fertility to coresidence at the beginning of the twentieth century (Smith 1986); see also Elman and Uhlenberg (1995).

The ultimate cultural determinist interpretation is Thornton (2005), who proposes a trickle-down theory of family change driven by political philosophers of the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Thornton argues that these European intellectuals formed incorrect theories of family change by using faulty comparative methodology. These false theories—including the theory that there had been a shift from extended to nuclear families—eventually trickled down to ordinary people and became a “developmental ideal.” According to Thornton’s theory, populations around the world then altered both their attitudes and behavior to conform to the ideal and began to reside in nuclear families.

In 1850, 69 percent of elderly married women resided with at least one child, compared with 72 percent of unmarried elderly women; thus, most women who became widowed were doubtless already residing with a child.

The average age difference between parents and children in 1850 was approximately 35 for men and 30 for women, so the average 35-year-old had a mother age 65 and a father age 70 (see Ruggles 2003).

The population census does not distinguish sharecroppers and tenant farmers from farm owners, so IPUMS data do not provide sufficient information to estimate the impact of farm ownership on the nineteenth-century race differential in living arrangements.

Some analysts, for example, confine themselves to widowed elderly women, measure the percent living alone, and cover a comparatively brief time interval; others look at residence with children, include all elderly persons, or cover a longer time span.

Income is available for only one individual in each household in 1950. An alternate approach is to limit the analysis to single women, but singles also often depended on others for support; fully 45 percent of unmarried women age 30 to 39 in 1950 reported little or no income of their own (under $1,000). If we focus solely on unmarried women, income has the largest effect on the older generation from 1950 to 1970 and the younger generation from 1980 to 2000.

The SAR model is highly effective in eliminating autocorrelation; Moran’s I is .09 for OLS Model 5 (p = .027) and .00 for SAR Model 6 (p = .429). The SAR models use a weight matrix derived from the percentage of shared boundaries between states. I am indebted to Mathew Creighton of the University of Pennsylvania for carrying out the spatial autocorrelation analysis. On methods of controlling spatial autocorrelation, see Bailey and Gatrell (1995) and Anselin (1988).

In both models, the difference between the coefficients for the younger and older generations is significant at the .01 level.

Social scientists have long recognized the potential for misleading results from geographic analysis (Robinson 1950). These models indicate that states with the greatest increases in income and education for the younger generation also had the greatest shift to independent residence for the elderly. By including state fixed-effects and controlling for spatial autocorrelation, I attempt to control for unobserved variables, but it remains possible that unmeasured changes in state characteristics affected the results. The analysis nevertheless supports the hypothesis that the decline of coresidence resulted more from changing characteristics of the younger generation than from changing characteristics of elders.

McGarry and Schoeni adjust the average benefit assigned to each widow depending on age and race, but the imputed benefits mainly depend on census year. Engelhart and colleagues (2002) also rely on chronological change in benefit levels to estimate the effects of Social Security on coresidence. In particular, they examine the “Social Security notch”—a short-lived increase in benefit levels. They find that as benefits declined after the notch, coresidence went up. As Messineo and Wojtkiewicz (2004) argue, however, that increase in coresidence resulted from a decline in marriage among youth, and it probably cannot be attributed to the notch.

McGarry and Schoeni also assess state-level Old Age Assistance/Supplemental Security Income (OAA/SSI) benefits, but they find comparatively small effects. This result differs from that of Costa (1999) who uses 1940 to 1950 average state OAA benefits to argue that Social Security accounts for substantial change in living arrangements between 1950 and 1990. Despite Costa’s ingenuity, the study is hampered by endogenous and unobserved variables. Some Southern and border states clearly had benefit increases and declining coresidence during the 1940s, but this is a slender reed to support Costa’s generalizations about the impact of Social Security over the subsequent four decades.

I used income groups of $2,500 increments from $1–$2,499 through $97,500–$99,999, in 2000 dollars. I created an additional category for those with $100,000 or more in income. The income of married couples is combined. Group-quarters residents are excluded from the analysis.

In the early twentieth century, observers commented on the decline in both economic circumstances and authority of the aged as a result of the shift from agricultural to industrial employment (e.g., Epstein 1928; Squier 1912), and this view was echoed in the academic literature (e.g., Cowgill 1974; Graebner 1980). More recently, revisionist scholars have challenged this decline; see Haber and Gratton (1994), Gratton (1996), and Carter and Sutch (1996). Lee (2000) offers a dissent from the revisionist interpretation.

The author is grateful for the comments and suggestions of Catherine Fitch, Miriam King, Carolyn Liebler, Evan Roberts, three anonymous reviewers, the editors of the ASR, and participants at several colloquia and the 2005 meeting of the Population Association of America, where earlier versions were presented. Mathew Creighton is responsible for the spatial autoregressive models, and I also received valuable advice on spatial analysis from Pétra Noble and David Van Riper.

References

- Abel Marjorie, Folbre Nancy. Women’s Market Participation in the Late 19th Century: A Methodology for Revising Estimates. Historical Methods. 1990;23:167–76. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin Luc. Spatial Econometrics: Methods and Models. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino William S. The Likelihood of Parent-Child Coresidence: Effects of Family Structure and Parental Characteristics. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:405–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Trevor C, Gatrell Anthony C. Interactive Spatial Data Analysis. New York: Prentice Hall; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkner Lutz. The Stem Family and the Developmental Cycle of the Peasant Household: An Eighteenth Century Austrian Example. American Historical Review. 1972;77:398–418. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan Axel, Hajivassiliou Vassilis, Kotlikoff Laurence J, Morris John N. Health, Children, and Elderly Living Arrangements: A Multiperiod Multinomial Probit Model with Unobserved Heterogeneity and Autocorrelated Errors. In: Wise DA, editor. Topics in the Economics of Aging. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1992. pp. 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bose Christine. Devaluing Women’s Work: The Undercount of Women’s Employment in 1900. In: Bose C, Feldberg R, Sokoloff N, editors. Hidden Aspects of Women’s Work. New York: Praeger; 1987. pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J Douglas. An American Philosophy of Social Security: Evolution and Issues. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Burch Thomas K. The Size and Structure of Families: A Comparative Analysis of Census Data. American Sociological Review. 1967;32:347–63. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess Ernest W. Family Structure and Relationships. In: Burgess EW, editor. Aging in Western Societies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1960. pp. 271–98. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John. Theory of Fertility Decline. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Carter Susan B, Gartner Scott Sigmund, Haines Michael R, Olmstead Alan L, Sutch Richard, Wright Gavin., editors. Historical Statistics of the United States. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]