Abstract

The Gram-negative periodontopathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) binds selectively to buccal epithelial cells (BECs) of human and Old World primates by means of the outer-membrane autotransporter protein Aae. We speculated that the exposed N-terminal portion of the passenger domain of Aae would mediate binding to BECs. By using a series of plasmids that express full-length or truncated Aae proteins in Escherichia coli, we found that the BEC-binding domain of Aae was located in the N-terminal surface-exposed region of the protein, specifically in the region spanning amino acids 201–284 just upstream of the repeat region within the passenger domain. Peptides corresponding to amino acids 201–221, 222–238 and 201–240 were synthesized and tested for their ability to reduce Aae-mediated binding to BECs based on results obtained with truncated Aae proteins expressed in E. coli. BEC-binding of E. coli expressing Aae was reduced by as much as 50 % by pre-treatment of BECs with a 40-mer peptide (201–240; P40). Aae was also shown to mediate binding to cultured human epithelial keratinocytes (TW2.6), OBA9 and TERT, and endothelial (HUVEC) cells. Pre-treatment of epithelial cells with P40 resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in binding and reduced the binding of both full-length and truncated Aae proteins expressed in E. coli, as well as Aae expressed in Aa. Fluorescently labelled P40 peptides reacted in a dose-dependent manner with BEC receptors. We propose that these proof-of-principle experiments demonstrate that peptides can be designed to interfere with Aa binding mediated by host-cell receptors specific for Aae adhesins.

INTRODUCTION

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) has been the subject of intense investigation since 1976 when it was discovered to be associated with localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP), an infection in young adolescents of African descent, which can result in premature tooth loss (Newman et al., 1976; Slots, 1976). Recently, this association has become more compelling in light of two longitudinal studies that have shown that healthy adolescents who harbour Aa have a significantly greater risk of developing disease than their age, gender-and race-matched controls (Fine et al., 2007; Haubek et al., 2008). In conjunction with these clinical studies, Aa has been shown to possess an array of virulence traits that are consistent with the pathogenesis of LAP. These traits include attachment and colonization factors, innate and acquired host-defence avoidance factors, and connective tissue and bone destructive factors (Fine et al., 2006; Fives-Taylor et al., 1999; Henderson et al., 2002). Aa attachment and colonization functions have been assigned to a variety of outer-membrane proteins that mediate binding to oral mucosal surfaces (Asakawa et al., 2003; Komatsuzawa et al., 2002). As such, these structures are presumed to be a prerequisite for Aa-initiated mucosal infections (Asakawa et al., 2003; Komatsuzawa et al., 2002). It has further been shown that Aa can be found in atheromatous plaques, and is one of several periodontal pathogens that have been associated with an increased risk of heart disease (Haraszthy et al., 2000; Kozarov et al., 2005). Taken together, these studies attest to the importance of understanding how Aa initiates disease at a molecular level. Our goal is to dissect the molecular events relating to binding so that novel diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic strategies can be discovered.

Recently, studies in humans have implicated the buccal mucosa as a primary site for Aa colonization and immune avoidance (Eger et al., 1996; Müller et al., 1996; Rudney et al., 2001). Along these lines, we and others have shown that Aa produces two autotransporter adhesins, Aae and ApiA, that account for its association with the oral mucosal epithelium (Asakawa et al., 2003; Fine et al., 2005; Komatsuzawa et al., 2002; Rose et al., 2003; Yue et al., 2007). In vitro studies have shown that if both the aae and apiA structural genes are mutated, the attachment of Aa to buccal epithelial cells (BECs) is completely abrogated (Yue et al., 2007). Moreover, Aa has been shown to attach to and penetrate endothelial cells, although the cellular events that direct that attachment are still unknown (Kusumoto et al., 2004; Schenkein et al., 2000). It is our premise that both Aae and ApiA could be instrumental in the attachment of Aa to tissues. Thus, the more we understand about the role of Aae and ApiA in the attachment of Aa to epithelial and endothelial surfaces, the more we can direct our work towards designing strategies to interfere with that attachment.

This study focused on the role of the autotransporter adhesin Aae in the attachment of Aa to epithelial cells with the goal of developing strategies to interfere with Aa binding. Our plan was to revisit methods developed for anti-adhesive therapeutic approaches to mucosal infections (Beachey, 1981; Cheney et al., 1980; Sellwood et al., 1975). It is well known that autotransporters contain three basic functional domains: an N-terminal signal peptide that directs the export of the protein through the inner membrane by a Sec-dependent mechanism, a C-terminal translocator domain that inserts into the outer membrane and forms a β-barrel structure with a central channel, and an internal passenger domain that is secreted through the channel in the β-barrel and presented on the cell surface (Henderson et al., 1998, 2004). Since the N-terminal passenger domain is exposed to the environment external to the bacterial cell, it is the likely region for binding to host cells (Fine et al., 2005). The passenger domain of autotransporter proteins often contains a series of repeat sequences (Henderson & Nataro, 2001). In the case of Aae, repeats in the passenger domain are clustered toward the amino terminus, the number of repeats varying from one to four depending on the strain (Fine et al., 2005; Rose et al., 2003). The exact function of the Aae repeats is unknown, but it is speculated that a greater number of repeats may be related to an increased binding of Aa to its target tissue (Rose et al., 2003). The goal of this work was to locate the region of the Aae passenger domain that influences Aa attachment to BECs and related epithelial cells, with the long-term goal of defining the minimal motif needed to prevent the initiation of disease.

METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Aa strains were cultured on AAGM agar plates or in AAGM broth (Fine et al., 1999), except that bacitracin and vancomycin were omitted from the media. All Aa cultures were grown in 10 % CO2. Escherichia coli strains were cultured on Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plates or in LB broth. Media were supplemented with kanamycin 50 μg ml−1; 1 mM IPTG was added when necessary. E. coli cultures were incubated in air at 37 °C with shaking (250 r.p.m.).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and PCR primers

| Strain, plasmid or primer | Relevant characteristics or sequence* | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans IDH 781 | Wild-type (serotype d) | Fine et al. (2005) |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans JK 1047 | IDH 781N flp-1 : : Tn903kan; Kmr | Yue et al. (2007) |

| E. coli DH5α | For expression of aae in E. coli | New England Biolabs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 TOPO | Cloning vector (Kmr) | Invitrogen |

| pGJD3 | pCR2.1 TOPO containing aae from Aa IDH 781 | This study |

| pΔ301–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ301–596) | This study |

| pΔ284–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ284–596) | This study |

| pΔ264–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ264–596) | This study |

| pΔ238–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ238–596) | This study |

| pΔ221–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ221–596) | This study |

| pΔ201–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ200–596) | This study |

| pΔ68–594 | pGJD3 with truncated aae (Δ67–596) | This study |

| pVK43 | pJAK16 containing aae from Aa CU 1000 (Cmr) | Fine et al. (2005) |

| PCR primers† | ||

| Aae-BamHI-F | GCGCGGATCCATAATGAAGAAAGTTTAGATGTGTTCTTTTTCAAAAAAGT | This study |

| Aae-PstI-R | TGCGCTGCAGCTACCAGTAATTCAGTTTTACACC | This study |

| Aae-Acc65I | CCAAGCTTGGTACCGAGCTC | This study |

| Aae-301 | GATAACCTCAGCTTCTTCTGCCTTTTGA | This study |

| Aae-284 | GATAACCTCAGCTTCTAAACGCTTGCGTT | This study |

| Aae-264 | GATAACCTCAGCTTGTTGGCGAAGTATTTCA | This study |

| Aae-238 | GATAACCTCAGCAACTTCGGCTAATTTAC | This study |

| Aae-221 | GATAACCTCAGCTTTAATCTTTTGGCGGG | This study |

| Aae-201 | GATAACCTCAGCTGCCAGCTGCTCTTTA | This study |

| Aae-120 | GATAAACCTCAGCTTCTTTTTGTGCCATCTC | This study |

| Aae-68 | GATAACCTCAGCCTGAGAAGACGGTTGA | This study |

*Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

†PCR primer sequences are shown in the 5′→3′ orientation. Restriction endonuclease cleavage sites are underlined. The aae start and stop codons are shown in bold.

Construction of aae wild-type and deletion mutant plasmids.

We constructed plasmids containing wild-type aae and seven different aae deletion mutants as follows. First, the full-length aae gene was amplified by PCR using primers Aae-BamHI-F and Aae-PstI-R (Table 1) and genomic DNA from Aa strain IDH 781 as a template. The PCR product (2759 bp) was inserted into plasmid pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting plasmid, designated pGJD3, contained aae in the orientation that placed the gene under control of the lac promoter. Next, IDH 781 genomic DNA was amplified by PCR with forward primer Aae-Acc65I combined with reverse primers Aae-301, Aae-284, Aae-264, Aae-238, Aae-221, Aae-201, Aae-120 and Aae-68 (Table 1) in eight different PCRs (primer orientations are described with respect to the direction of transcription). Forward primers were engineered to contain an Acc65I restriction site. The PCR products were digested with Acc65I and Bpu10I and ligated into the Acc65I/Bpu10I restriction sites of pGJD3. The Acc65I and Bpu10I recognition sequences correspond to bp −83 to −78 upstream of the aae start codon located in the backbone of pCR2.1-TOPO in pGJD3, and bp 1783 to 1789 in the aae gene, respectively (Fig. 1a). The ligation reactants were transformed into E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells (Invitrogen) and transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by restriction endonuclease digestion (Fig. 1b) and DNA sequence analysis.

Fig. 1.

Physical maps of wild-type and mutant A. actinomycetemcomitans Aae proteins. The horizontal arrow in (a) represents the wild-type Aae protein (907 aa). Also shown are a map of the Aae protein domains (signal peptide, passenger domain and β domain); the locations of amino acid difference between Aae from strains CU 1000 and IDH 781; the locations of the four characteristic Aae amino acid repeat sequences; the location of the sequence corresponding to the synthetic peptides used to block Aae-mediated binding; the locations of the Acc65I and Bpu10I restriction sites used to construct Aae deletion mutant plasmids; and a scale in amino acid residues. (b) Physical maps of wild-type and deletion mutant Aae proteins encoded by the plasmids indicated on the left.

Isolation of human buccal epithelial cells.

Human buccal epithelial cells (BECs) were collected from healthy adult volunteers as previously described (Fine et al., 2005). Collection of BECs from human volunteers was approved by the UMDNJ Institutional Review Board. Cells were diluted to approximately 5×104 c.f.u. ml−1 using a haemocytometer. The absence of endogenous bacteria was confirmed by spreading BECs onto LB plates containing kanamycin 50 μg ml−1 as well as on AAGM agar plates.

Buccal epithelial cell binding.

The BEC binding assay was performed as described previously (Fine et al., 2005; Yue et al., 2007). Briefly, 48-h-old cultures of Aa strain IDH 781 were rinsed three times with PBS, scraped from the culture dishes with a cell scraper and then vigorously vortexed to disperse cell aggregates. The E. coli cells were prepared by inducing exponential-phase cultures with IPTG (final concentration of 1 mM) for 3 h. Aa or E. coli cells were adjusted to OD590 0.8. A total of 200 μl of Aa or E. coli cells at a concentration of ∼109 c.f.u. ml−1 was added to 200 μl BECs (at a concentration of 1×105 cells ml−1) in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube to achieve a ratio of 104 bacterial cells per BEC. The tube was rotated at 20 r.p.m. at 37 °C for 60 min. One hundred microlitres of the mixture of bacteria and BECs was placed on the top of a 10 ml gradient of 5 % Ficoll 400 suspended in PBS contained in a 15 ml centrifuge tube. The tube was centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min to separate unbound bacteria from the heavier BECs, which pelleted to the bottom of the tube. The supernatant was removed carefully by pipette and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl PBS. Resuspended cells were serially diluted and plated on agar for c.f.u. enumeration. Controls included BECs with no bacteria, and bacteria alone with no BECs. Results were calculated as c.f.u. ml−1 and then converted to c.f.u. per BEC.

Cell culture techniques.

Cell lines were cultured in six-well or twelve-well tissue culture plates (Becton/Dickinson). Cell line TW2.6, a buccal epithelial cell line, was a kind gift from Dr Mark Y. P. Kuo (School of Dentistry, National Taiwan University). TW2.6 buccal epithelial cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham's F12 medium (3 : 1) (Gibco) with 5 % antibiotics and 15 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) as previously described (Kok et al., 2007). An immortalized human gingival epithelial cell line (OBA-9) and a human oral mucosal keratinocyte line which ectopically expressed a telomerase catalytic subunit (OKF6/TERT-1) were kind gifts from Dr Gill Diamond (New Jersey Dental School). OBA-9 and OKF6/TERT-1 cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium, supplemented with 0.05 % bovine pituitary extract and 5 ng recombinant epidermal growth factor ml−1 (Invitrogen). Additional CaCl2 was added to the medium to a final concentration of 0.4 mM (Kusumoto et al., 2004). Pooled human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Lonza and cultured in EBM-2 complete medium according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that additional FBS was added to attain a final concentration of 10 %. All cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 in air.

Binding of E. coli to cultured cells.

Cell lines were cultured to approximately 85–90 % confluence. The cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed once in PBS and adjusted to a concentration of 105 cells ml−1. The E. coli suspensions were prepared as described above. After Ficoll separation, the resulting pellets were resuspended, serially diluted and plated on LB agar containing kanamycin or chloramphenicol (50 μg ml−1) in order to determine c.f.u. ml−1 which was then converted to bacterial cells ml−1.

Blocking epithelial cell binding with synthetic peptides.

Three peptides, P21 (AQKEAERLANEQEIARQKIKA), P17 (NELQRAINEQSKLAEVA) and P40 (AQKEAERLANEQEIARQKIKANELQRAINEQSKLAEVARV), were chemically synthesized, by CHI SCIENTIFIC, to 99 % purity. These peptides correspond to amino acids 201–221, 222–238 and 201–240, respectively, in Aae. Peptides were added to the cultured cells, after treatment with a blocking buffer, to achieve a concentration of 0.1–100 μg ml−1. Control cells were treated with no peptide. After 1 h at room temperature, bacteria were added to the cells and the binding assay was performed as described above.

Fluorescently labelled peptide binding assay.

TW2.6 cells were cultured in 96-well microtest tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson). When 85 % confluence was achieved, cells were washed three times with ice-cold HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES, 128 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgSO4, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 5 % heat-inactivated FBS). HEPES buffer containing 3 % BSA (blocking buffer) was added for 2 h to block non-specific binding. FITC-conjugated peptide P40 dissolved in HEPES buffer was added to the wells to achieve a concentration of 0–250 μM. The plates were then incubated at room temperature for 2 h. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were rinsed three times with HEPES buffer and the fluorescence was quantified by a Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BIO-TEK Instruments). The background level of binding was measured in wells without TW2.6 cells.

Statistics.

All assays were performed in triplicate at a minimum. One-way ANOVA comparison was followed by post-hoc Tukey–Kramer testing for pairwise analysis. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Construction of plasmids encoding wild-type and mutant Aae proteins

The aae gene from Aa strain IDH 781 was amplified by PCR and then ligated into plasmid vector pCR2.1 TOPO, resulting in plasmid pGJD3 (Fig. 1a). Experiments were designed to use pVK43 initially but, due to difficulties with the targeted restriction sites required to make deletion mutants, it was more efficient to design cassettes with truncated PCR products containing specific amino acid residues expressed in a PCR2.1 TOPO plasmid using E. coli DH5α as the host. The predicted amino acid sequence of IDH 781 Aae was 96 % identical to that of Aae from strain CU 1000 (Fine et al., 2005). Nearly all of the amino acid changes, including a 5 aa deletion in IDH 781, occurred in the region that encodes the C-terminal half of the passenger domain, which was not related to the functional binding region (Fig. 1a). The N-terminal half of the passenger domain and the β domain were very highly conserved (>99 % identity, which showed differences in amino acids downstream of the functional adhesin; see Supplementary Fig. S1, available with the online version of this paper). The IDH 781 and CU 1000 Aae proteins both contained four copies of the characteristic Aae amino acid repeat sequence (Fine et al., 2005) (Fig. 1a).

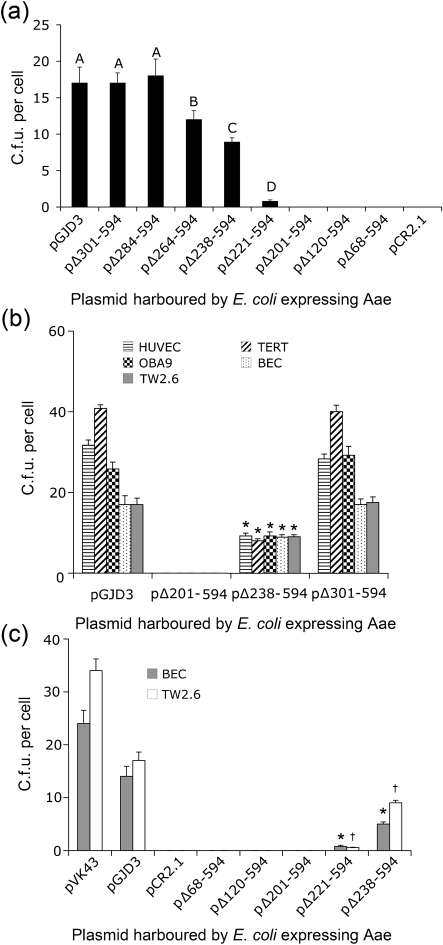

A series of plasmids containing in-frame deletions in IDH 781 aae was also constructed (Fig. 1b). Plasmid pΔ68–594 contained a deletion of the entire passenger domain and plasmid pΔ301–594 contained a deletion of the C-terminal half of the passenger domain, including the four Aae amino acid repeat sequences (Fig. 1b). Based on preliminary cell binding assays with E. coli cells harbouring plasmids pGJD3, pΔ68–594 and pΔ301–594 (Fig. 2a), we concluded that the epithelial cell binding domain in Aae was located between amino acids 68 and 301. We therefore constructed a series of plasmids that encoded sequential deletions within this region (pΔ301–594, pΔ284–594, pΔ264–594, pΔ238–594, pΔ221–594, pΔ201–594, pΔ120–594 and pΔ68–594) (Figs 1b and 2a).

Fig. 2.

Binding of plasmid-harbouring E. coli DH5α cells to freshly isolated human BECs and cultured epithelial cells. (a) Binding of E. coli harbouring the indicated plasmid expressing deletion mutant Aae to BECs. Values show mean c.f.u. per epithelial cell for three independent experiments and error bars indicate sd. Bars with different letters indicate values that were significantly different from each other by ANOVA and post-hoc pairwise testing. (b) Comparison of binding of E. coli DH5α to cells of epithelial origin when expressing Aae and truncated varieties of Aae proteins. BECs, HUVECs, TERT, OBA9 and TW2.6 cells are compared. Similarity between TW2.6 cells and BECs is seen when binding of full-length Aae and truncated versions of Aae protein are compared. Significant differences (P<0.05) for all cell types are seen when full-length Aae is compared to 238–594 aa truncated proteins. * Significantly lower binding to corresponding epithelial cells versus full-length expressed Aae (pGJD3). (c) Direct comparison of binding of E. coli DH5α to BECs and TW2.6 cells when E. coli expresses aae from pVK43 versus pGJD3. Plasmid pVK43 expressing Aae in DH5α binds at a higher level than that seen for pGJD3. DH5α expressing 201–594, 221–594 and 238–594 aa truncated proteins show significant reductions (P<0.05) in binding to their corresponding epithelial cell type (* for BEC, † for TW2.6 cells) when compared to DH5α expressing full-length protein.

BEC binding of full-length Aae and truncated proteins expressed in E. coli

We measured the binding ability of E. coli DH5α cells harbouring pGJD3 and the eight aae deletion mutants harbouring plasmids with deletions between amino acids 68 and 301 as listed above. In these experiments neither the pCR2.1- (empty plasmid vector) nor the pΔ68–594-, pΔ120–594-, or pΔ201–594-harbouring cells bound to BECs, suggesting that amino acids 68–201 have nothing to do with binding to epithelial cells. Modest binding was restored in pΔ221–594-harbouring cells and almost half of the total binding was restored in pΔ238–594-harbouring cells, suggesting that residues 201–238 could be involved in binding. Some modest additional binding was seen in pΔ264–594-harbouring cells, while still greater binding was restored in pΔ284–594-harbouring cells. Overall complete restoration of binding was seen from amino acids 201 to 284, suggesting that the binding domain of interest should include these amino acid residues (Fig. 2a).

Aae mediates bacterial binding to various oral epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells

We also measured the ability of E. coli cells harbouring Aae-expressing plasmids to bind to OKF6/TERT-1, OBA9, HUVEC and TW2.6 cells and BECs (Fig. 2b). Our goal was to expand our assessment beyond BECs to cultured epithelial cells that could be collected in a more controlled manner. For convenience we limited our testing to plasmids that expressed full-length Aae (pGJD3), no Aae (pΔ201–594), truncations that produced minimal Aae (pΔ238–594), and truncated proteins that restored Aae binding completely (pΔ301–594). Complete reduction in binding was exhibited by cells harbouring plasmid pΔ201–594, while minimal binding was restored by plasmid pΔ238–594 when compared to the full-length protein expressed by pGJD3. Binding was fully restored by plasmid pΔ301–594. These data support the hypothesis that amino acid residues from 301 to 594 have no effect on binding and that the Aae epithelial binding domain is located between amino acids 201 and 301. The BEC and TW2.6 binding patterns of all Aae-harbouring plasmids expressed in E. coli cells were similar, suggesting that TW2.6 cells could be used as surrogates for BECs (Fig. 2b).

We further compared binding of Aae expressed from plasmids pVK43 and pGJD3 to BECs and TW2.6 cells (Fig. 2c). Our data show that Aae expressed from pVK43 bound at significantly higher levels than that those seen in pGJD3 (P<0.05). It is likely that plasmid expression levels are responsible for these differences (Supplementary Figs S1, S2). Nevertheless, binding differences between BECs and TW2.6 cells were similar in both pVK43 and pCR2.1 cells, reinforcing the sense that TW2.6 cells could act as a reasonable surrogate for BECs.

Due to these results, and as a proof-of-principle strategy, we chose to synthesize peptides derived from amino acid sequences 201–221, 222–238 and 201–240 to test their ability to reduce binding to epithelial cells. These peptides were designed to test the principle that specific peptides could be used to block Aae-mediated binding.

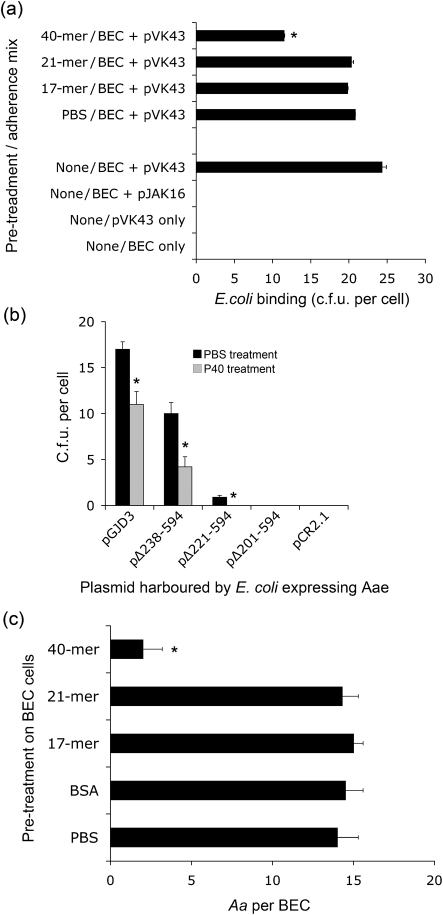

Peptides block binding of Aae to BECs

Only the 40-mer (P40), as opposed to P17 or P21, blocked binding of the Aae harboured in plasmid pVK43 and expressed in E. coli (Fig. 3a). No effect was seen by pre-treating BECs with either the 17-mer or the 21-mer. This result differs from that seen when the truncated proteins are expressed in E. coli. Differences could result from conformational distinctions between the expressed proteins and the synthesized peptides. It was shown that P40 peptide pre-treatment can reduce binding of both the full-length (pGJD3) and the truncated Aae proteins (pΔ238–594, pΔ221–594; P<0.05) (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that both the full-length and the truncated proteins are surface expressed. Fig. 3(c) illustrates the effect of the P40 peptide on Aae expression in Aa strain JK 1047, an flp-mutant strain (Table 1). Here, bacterial binding is reduced from 14 to 2 JK 1047 cells BEC−1 (P<0.05). Neither the 17-mer nor the 21-mer, nor pre-treatment with BSA, had any effect on binding of JK 1047 to BECs. This Flp-negative strain was used because, unlike the parent wild-type strain (IDH 781), JK 1047 does not autoaggregate. As a result, JK 1047 provides a way to measure receptor–adhesin interaction in native Aa strains not showing autoaggregation.

Fig. 3.

Effect of synthetic peptides on Aae binding to epithelial cells. (a) BECs were pre-treated with 17-mer, 21-mer and 40-mer (P40) peptides at a dose of 100 μM. Reduction in binding is seen only in the case of P40. * Significantly lower (P<0.05) binding by ANOVA. (b) Effect of P40 peptide on the ability of E. coli expressing truncated proteins to bind to BECs. The data show that binding is reduced by pre-treatment of BECs with P40 peptide, indicating surface expression of truncated proteins. Peptide was added at 100 μM. *, P<0.05. (c) Effect of various peptides (17-, 21- and 40-mer) on binding of Aa strain JK 1047 (flp-mutant expressing aae and apiA) to BECs. Pre-treatment of BECs with P40 significantly (* P<0.05) reduces binding of JK 1047 at the concentration of JK 1047 added. Only the P40 peptide reduced binding. All experiments were done in triplicate and values are expressed as means±sd.

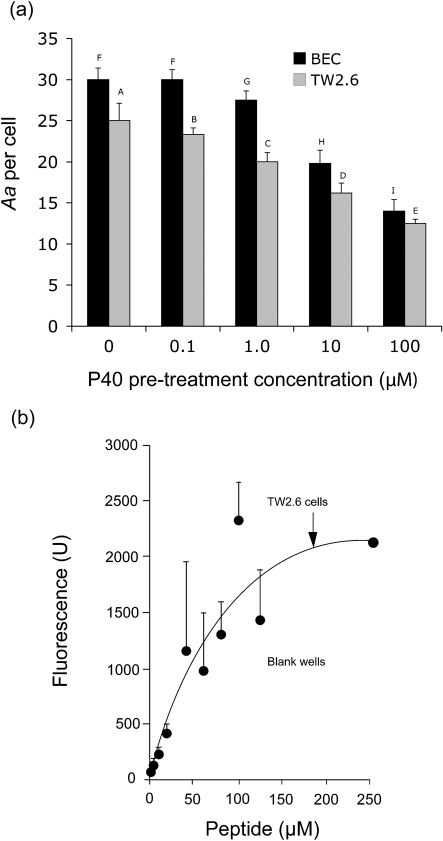

The P40 peptide pre-treatment of both the BECs and TW2.6 cells reduced binding in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 4(a). Peptide levels of 1.0 μM and above significantly reduced binding (P<0.05). A fluorescently labelled P40 peptide was used to demonstrate that P40 bound to TW2.6 cells in a dose-dependent manner, showing a trend toward saturation (Fig. 4b). These findings suggest that peptide P40 blocked the interaction of Aae with its BEC receptor by binding it in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 4.

Dose-dependent interaction of P40 peptide with BECs and TW2.6 cells. (a) Effect of P40 pre-treatment of BECs and TW2.6 cells on binding of A. actinomycetemcomitans JK 1047. P40 doses of 1.0, 10 and 100 μM show significant reductions in binding (P<0.05), indicating a P40 dose-dependent inhibition of binding to BECs and TW2.6 cells. Bars with different letters are significantly different from each other by ANOVA and post-hoc pairwise testing. (b) Fluorescently labelled peptide P40 binds to TW2.6 cells in a dose-dependent manner. TW2.6 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of labelled peptide. The amount of fluorescence as measured suggests saturation of TW2.6 receptor sites. Blank wells (untreated TW2.6) were used as control (data not shown). Data are presented as the means±sd of three independent experiements.

DISCUSSION

Several years ago, receptor and adhesin analogue therapy or anti-adhesive therapy was introduced as a new way of interfering with mucosal infections (Aronson et al., 1979; Beachey & Courtney, 1987; Cheney et al., 1980; Simpson & Beachey, 1983). The premise suggested that by blocking bacterial–tissue interactions, anti-adhesive therapy could alter the manifestation of disease without the need to kill the infecting micro-organism (Sellwood et al., 1975; Ukkonen et al., 2000). The experiments presented in this report were designed to revisit the anti-adhesive therapeutic approach in relation to Aa-induced infections.

Aa expresses two autotransporter adhesins, Aae and ApiA, that are involved in mucosal binding (Fine et al., 2006). It is interesting to note that the two autotransporter adhesins show specificity for the same epithelial tissue surfaces and mammalian species (Yue et al., 2007). Since both Aae and ApiA mediate Aa binding to BECs, perhaps a functional overlap exists between these two autotransporters. This overlap or redundancy could suggest that BEC binding is of great importance to the survival of Aa in the mucosal domain of the oral cavity of humans and Old World primates. While this area needs further exploration it is known that Aae binds at low cell density while ApiA binds only at high cell density (Fine et al., 2005). Since both autotransporter adhesins are involved in binding to BECs, our effort to block Aa binding by interfering with one adhesin could prove to be a challenge.

This potential redundancy has led us to think of these autotransporters in the context of the temporal events associated with mucosal infections. In the early stages of infection, during the incubation and prodromal periods, Aa would be present at low cell densities, but as disease ensues, Aa cell densities would increase in the local environment (Fine et al., 2006). Since our P40 peptide functioned better at low cell density (the data shown in Fig. 3 were obtained at a low density of added cells) we would predict that it would be effective in the early stages of infection. In contrast, minimal reduction of BEC binding by peptide P40 was seen when Aa cells were added at a high density since ApiA was also active (data not shown), suggesting that our peptide would be minimally effective as a therapeutic intervention. This area also needs further exploration.

The Aae passenger domain is displayed on the cell surface and thus would appear to be capable of interacting with the outside environment (Fine et al., 2005). Our experimental data, and those of others, have indicated that Aa strains have passenger domains containing repeat sequences that vary in the number of repeat motifs (Fine et al., 2005; Rose et al., 2003). As a result we have tried to assess the functional changes in binding related to these repeats (Fine et al., 2006; Henderson et al., 2004). While Rose et al. (2003) proposed that increasing the number of Aae repeats results in increased binding, data from the current study do not support this contention. Our results suggest that Aae-mediated binding to BECs resides between amino acids 201–284 and lies immediately upstream of the Aae repeat domain. We have also observed that different strains of Aa, differing in the number of Aae repeats, do not differ in the amount of binding seen (data not shown).

In our studies, the P40 peptide reduced binding to BECs by at least 50 % (Fig. 3a–c). There are at least two possible explanations that can be offered as to why the P40 peptide did not completely abrogate Aae-mediated binding. First, the P40 peptide does not represent the Aae protein adhesin binding domain in its entirety (Fig. 2a). Second, since conformational differences exist between peptides and expressed proteins, the peptides may not provide a completely accurate representation of the Aae protein adhesin. This second point may not be valid since our results with the P40 peptide appear to account for a similar reduction in binding when compared to the truncated protein as expressed in E. coli. These issues will be resolved in future studies.

In conclusion, we have evidence that within the Aae autotransporter adhesin domain there is a motif of 40 aa that accounts for a large percentage of its interaction with epithelial cells. Our effort was to evaluate this 40 aa sequence and to translate this information into a strategy that could be used to interfere with Aa binding. Experiments presented in this report were first performed by deletion analysis and then confirmed by peptide blocking studies. While the information obtained does not account for the entire binding capacity of Aa to the epithelium, it should suggest ways to design future experiments. Our long-term goal is to discover ways to completely block the binding of this oral pathogen to its target tissue and thus develop methods for anti-adhesive therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark Y. P. Kuo of the National Taiwan University School of Dentistry for providing TW2.6 cells and Dr Gill Diamond of the New Jersey Dental School for providing OBA-9 and OKF6/TERT-1 cells. This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, grant no. DE016306 to D. H. F.

Abbreviations

Aa, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

BECs, buccal epithelial cells

FBS, fetal bovine serum

LAP, localized aggressive periodontitis

HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Footnotes

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession number for the aae gene sequence of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans strain IDH 781 is FJ744750.

Two supplementary figures are available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Aronson, M., Medalia, O., Schori, L., Mirelman, D., Sharon, N. & Ofek, I. (1979). Prevention of colonization of the urinary tract of mice with Escherichia coli by blocking of bacterial adherence with methyl α-d-mannopyranoside. J Infect Dis 139, 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, R., Komatsuzawa, H., Kuwai, T., Yamada, S., Goncalves, R. B., Izumi, S., Fujiwara, T., Nakano, Y., Suzuki, N. & other authors (2003). Outer membrane protein 100, a versatile virulence factor of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol Microbiol 50, 1125–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachey, E. H. (1981). Bacterial adherence: adhesin–receptor interactions mediating the attachment of bacteria to mucosal surfaces. J Infect Dis 143, 325–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachey, E. H. & Courtney, H. S. (1987). Bacterial adherence: the attachment of group A streptococci to mucosal surfaces. Rev Infect Dis 9, S475–S481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, C. P., Schad, P. A., Formal, S. B. & Boedeker, E. C. (1980). Species specificity of in vitro Escherichia coli adherence to host intestinal cell membranes and its correlation with in vivo colonization and infectivity. Infect Immun 28, 1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger, T., Zoller, L., Muller, H.-P., Hoffmann, S. & Lobinsky, D. (1996). Potential diagnostic value of sampling oral mucosal surfaces for Actinobacillus acintomycetemcomitans in young adults. Eur J Oral Sci 104, 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, D. H., Furgang, D., Schreiner, H. C., Goncharoff, P., Charlesworth, J., Ghazwan, G., Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P. & Figurski, D. H. (1999). Phenotypic variation in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans during laboratory growth: implications for virulence. Microbiology 145, 1335–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, D. H., Velliyagounder, K., Furgang, D. & Kaplan, J. B. (2005). The Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans autotransporter adhesin Aae exhibits specificity for buccal epithelial cells from humans and Old World primates. Infect Immun 73, 1947–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, D. H., Kaplan, J. B., Kachlany, S. C. & Schreiner, H. C. (2006). How we got attached to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a model for infectious diseases. Periodontol 2000 42, 114–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine, D. H., Markowitz, K., Furgang, D., Fairlie, K., Ferrandiz, J., Nasri, C., McKiernan, M. & Gunsolley, J. (2007). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and its relationship to initiation of localized aggressive periodontitis: a longitudinal cohort study of initially healthy adolescents. J Clin Microbiol 45, 3859–3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fives-Taylor, P. M., Meyer, D. H., Mintz, K. P. & Brissette, C. (1999). Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol 2000 20, 136–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraszthy, V. I., Zambon, J. J., Trevisan, M., Zeid, M. & Genco, R. J. (2000). Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol 71, 1554–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubek, D., Ennibi, O.-K., Poulsen, P., Vaeth, M. & Kilian, K. (2008). Risk of aggressive periodontitis in adolescent carriers of the JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans in Morocco: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 371, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, I. R. & Nataro, J. P. (2001). Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect Immun 69, 1231–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, I. R., Navarro-Garcia, F. & Nataro, J. P. (1998). The great escape: structure and function of the autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol 6, 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, B., Wilson, M., Sharp, L. & Ward, J. M. (2002). Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Med Microbiol 51, 1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, I. R., Navarro-Garcia, F., Desvaux, M. J., Fernandez, R. C. & Ala'Aldeen, D. (2004). Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68, 692–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok, S. H., Hong, C. Y., Lin, S. K., Lee, J. J., Chiang, C. P. & Kuo, M. Y. (2007). Establishment and characterization of a tumorigenic cell line from areca quid and tobacco smoke-associated buccal carcinoma. Oral Oncol 43, 639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuzawa, H., Asakawa, R., Kawai, T., Ochiai, K., Fujiwara, T., Taubman, M. A., Ohara, M., Kurihara, H. & Sugai, M. (2002). Identification of six major outer membrane proteins from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Gene 288, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozarov, E. V., Dorn, B. R., Shelburne, C. E., Dunn, W. A., Jr & Progulske-Fox, A. (2005). Human atherosclerotic plaque contains viable invasive Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25, e17–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumoto, Y., Hirano, H., Saitoh, K., Yamada, S., Takedachi, M., Nozaki, T., Ozawa, Y., Nakahira, Y., Saho, T. & other authors (2004). Human gingival epithelial cells produce chemotactic factors interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 after stimulation with Porphyromonas gingivalis via Toll-like receptor 2. J Periodontol 75, 370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, H.-P., Zöller, L., Eger, T., Hoffmann, S. & Lobinsky, D. (1996). Natural distribution of oral Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in young men with minimal periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res 31, 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M. G., Socransky, S. S., Savit, E. D., Propas, D. A. & Crawford, A. (1976). Studies of the microbiology of periodontosis. J Periodontol 47, 373–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, J. E., Meyer, D. H. & Fives-Taylor, P. M. (2003). Aae, an autotransporter involved in adhesion of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to epithelial cells. Infect Immun 71, 2384–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudney, J. D., Chen, R. & Sedgewick, G. J. (2001). Intracellular Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in buccal epithelial cells collected from human subjects. Infect Immun 69, 2700–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkein, H. A., Barbour, S. E., Berry, C. R., Kipps, B. & Tew, J. G. (2000). Invasion of human vascular endothelial cells by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans via the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Infect Immun 68, 5416–5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellwood, R., Gibbons, R. A., Jones, G. W. & Rutter, J. M. (1975). Adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to pig intestinal brush borders: the existence of two pig phenotypes. J Med Microbiol 8, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, W. A. & Beachey, E. H. (1983). Adherence of group A streptococci to fibronectin on oral epithelial cells. Infect Immun 39, 275–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots, J. (1976). The predominant cultivable organisms in juvenile periodontitis. Scand J Dent Res 84, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukkonen, P., Varis, K., Jernfors, M., Herva, E., Jokinen, J., Ruokokoski, E., Zopf, D. & Kilpi, T. (2000). Treatment of acute otitis media with an antiadhesive oligosaccharide: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 356, 1398–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue, G., Kaplan, J. B., Furgang, D., Mansfield, K. G. & Fine, D. H. (2007). A second Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans autotransporter adhesin that exhibits specificity for buccal epithelial cells of humans and Old World primates. Infect Immun 75, 4440–4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]