Abstract

From June 1997 to December 2001, results of in vitro susceptibility tests of yeast isolates from 35 countries were collected. For 2001 alone, fluconazole results were reported for 22,111 yeast isolates from 77 institutions in 30 countries. Of these isolates, 18,569 were also tested for susceptibility to voriconazole. All study sites tested clinical yeast isolates by recently endorsed NCCLS disk diffusion method M44-P. Disk test plates were automatically read and results were recorded with the BIOMIC Image Analysis System. Species, drug, zone diameter, susceptibility category, MIC, and quality control results were electronically submitted by e-mail quarterly for analysis. Duplicate test results (same patient and same species with same sensitivity-resistance profile and biotype results during any 7-day period) and uncontrolled test results were eliminated from this analysis. The proportion of Candida albicans isolates decreased from 69.7% in 1997 to 1998 to 63.0% in 2001, and this decrease was accompanied by a concomitant increase in C. tropicalis and C. parapsilosis. The susceptibility (susceptible [S]or susceptible-dose dependent [S-DD]) of C. albicans isolates to fluconazole was virtually unchanged, from 99.2% in 1997 to 99% in 2001; the C. glabrata response to fluconazole was unchanged, from 81.5% S or S-DD in 1997 to 81.7% in 2001, although the percentage of resistant isolates from blood and upper respiratory tract samples appeared to increase over the study period; the percentage of S C. parapsilosis isolates decreased slightly, from 98% S or S-DD in 1997 to 96% in 2001; and the percentage of S isolates of C. tropicalis increased slightly, from 95.7% in 1997 to 96.9% in 2001. The highest rate of resistance to fluconazole among C. albicans isolates was noted in Ecuador (7.6%, n = 250). Results from this investigation indicate that the susceptibility of yeast isolates to fluconazole has changed minimally worldwide over the 4.5-year study period and that voriconazole demonstrated 10- to 100-fold greater in vitro activity than fluconazole against most yeast species.

Systemic yeast infections are a common consequence of immunosuppression, long-term indwelling catheters, and endocrinopathies. Subcutaneous, cutaneous, and superficial yeast infections also occur in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent populations. Fluconazole is commonly used for serious mucocutaneous and systemic disease, as well as for postsurgical and posttransplant prophylaxis. Given the widespread use of this agent, concerns about the development of resistance in yeast have been raised (11, 17, 22).

Recently, a new extended-spectrum triazole, voriconazole (Vfend; Pfizer), has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line treatment of invasive aspergillosis and for treatment of patients refractory to other therapies for serious infections caused by Scedosporium apiospermum and Fusarium spp. In Europe, voriconazole has been approved for treatment of invasive aspergillosis, treatment of fluconazole-resistant serious invasive Candida (including Candida krusei) infections, and treatment of serious fungal infections by Scedosporium spp. and Fusarium spp. A major advantage of voriconazole over other recently approved antifungal agents used to treat systemic disease is that it can be administered orally after initial intravenous loading and administration of maintenance doses. While voriconazole does not yet have an FDA-approved indication for the treatment of Candida infections, phase III clinical trials are ongoing and voriconazole has shown enhanced activity against various yeast species in vitro (3, 10, 19).

Breakpoints (susceptible [S], susceptible-dose dependent [S-DD], and resistant [R]) for fluconazole have been established (20), making in vitro susceptibility test results useful to help guide antifungal therapy. Breakpoints for voriconazole have not yet been established. Pharmacokinetically, fluconazole differs from voriconazole in that its concentration in serum is dependent on the dose administered; i.e., a higher dose of fluconazole leads to a higher concentration in serum (and hence the use of the S-DD designation) (6). The approved dosing regimen for voriconazole is two loading doses of 6 mg/kg given intravenously 12 h apart, followed by 4 mg/kg (or 3 mg/kg if tolerance is a problem) every 12 h as a maintenance dose (5). Patients (>40 kg) may be switched at any time to oral therapy with 200 mg every 12 h or an increase to 300 mg every 12 h if an inadequate response is evident. The adult dosing regimen should yield a Cmax in plasma of approximately 2 to 5 μg/ml.

In the present study, entitled the ARTEMIS DISK Surveillance Study, we evaluated global trends in the susceptibility of yeasts to fluconazole over a 4.5-year period by using the NCCLS M44-P disk diffusion method, in which zone sizes have been correlated with established breakpoints. We also evaluated yeast susceptibility to voriconazole by this disk method. The disk method was used because it provides a low-cost, reproducible, and accurate susceptibility test that can easily be adapted in hospital laboratories worldwide. This method should help to guide clinical therapy, provide epidemiology data, and reduce the number of misleading reports of drug resistance based on biased selective testing. We report the results of this global survey and a comparison of the activities of fluconazole and voriconazole against a large number of clinical isolates and a broad range of yeast species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test sites.

Eighty-nine sites in 35 countries contributed some data during the 4.5-year study period (June 1997 to December 2001), and 77 sites in 30 countries contributed data in 2001. All yeasts considered pathogens from all body sites and isolated from patients in all in-hospital locations during the study period were tested. Yeasts considered by the investigator to be colonizers, that is, not exhibiting pathology, were excluded. Identification of isolates was performed in accordance with each site's routine methods.

Susceptibility test method.

The NCCLS M44-P method is similar to the NCCLS M2-A6 disk test method for bacteria (13), except that Mueller-Hinton agar is supplemented with 2% glucose (to support growth) and 0.5 μg of methylene blue (improves zone edge definition) per ml. Mueller-Hinton agar medium was obtained locally at all sites. The inoculum was adjusted to match a 0.5 McFarland density standard. Plates were incubated for 18 to 24 h at 35 to 37°C. Slowly growing isolates, primarily members of the genus Cryptococcus, were read after 48 h of incubation. The method used in this study varied from NCCLS M44-P only in incubation time; 18 to 24 h versus 20 to 24 h in M44-P.

Pfizer Inc. supplied study sites with 25-μg fluconazole disks, 1-μg voriconazole disks (manufactured by Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.), quality control (QC) strain C. albicans ATCC 90028 (recommended acceptable-performance range of 28 to 39 mm for fluconazole and 31 to 42 mm for voriconazole), and an optional QC strain, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 (reference range of 22 to 33 mm for fluconazole and 28 to 37 mm for voriconazole).

Interpretive breakpoints for fluconazole disk diffusion testing (12) were based on zones correlated with NCCLS-recommended category breakpoints for the reference broth dilution method (14). In January 2003, the NCCLS Antifungal Susceptibility Subcommittee issued formal fluconazole disk interpretive criteria, as well as QC ranges for reference strains, for both fluconazole and voriconazole. The fluconazole MIC breakpoints are as follows: S, ≤8 μg/ml; S-DD, 16 to 32 μg/ml; R, ≥64 μg/ml. The corresponding zone interpretive criteria are as follows: S, ≥19 mm; S-DD, 15 to 18 mm; R, ≤14 mm. MICs reported in this study were automatically calculated by the BIOMIC System software (Giles Scientific Inc., Santa Barbara, Calif.; www.biomic.com). The BIOMIC MICs are determined by a method that is basically the same as the Etest. The continuous agar disk gradient is calibrated against NCCLS reference broth method MIC results on a group of isolates and then that “scale” (disk or Etest zone versus MIC in BIOMIC software or printed on the Etest) is used to “look up the MIC.” The regression data used by the BIOMIC software were provided to NCCLS during review of the yeast disk method and interpretive-QC guidelines (A. Barry and S. Brown, data on file). Other investigators have shown that zone sizes correlate well with broth dilution MICs and that the BIOMIC-interpreted MICs are as reliable as those obtained by Etest (16, 17). QC tests were required to be acceptable within 7 days of testing.

Data analysis.

All yeast disk test results were read by electronic image analysis and interpreted and recorded by a BIOMIC Plate Reader System (Giles Scientific Inc.). Test results were sent by e-mail to Giles Scientific for analysis. Zone diameter, susceptibility category (S, S-DD, or R), MIC, and QC test results were recorded electronically. Patient and doctor names, duplicate test results (same patient-same species-same biotype results), and uncontrolled results were automatically eliminated prior to analysis.

RESULTS

Isolation rates by species.

In each year of the study, the most commonly isolated yeast was C. albicans (Table 1). A decreasing trend in the rate of C. albicans isolation (6.74%) was evident over the 4.5-year period, along with increasing rates of isolation of C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. rugosa totaling 7.1%. Unusual yeasts, such as C. pelliculosa, Pichia species, and C. zeylanoides, were reported during the last 2 years of the study but contributed only 1.12% of the total year 2001 isolates. Unidentified (“other”) yeasts represented 0.51 to 3.07% of the total number of isolates; this percentage tended to decrease during the last 2 years, as more isolates were apparently identified to the species level. The species most commonly isolated from blood specimens were, in descending order, C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, and C. guilliermondii, and those from intensive care units (ICUs) were C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis and C. krusei.

TABLE 1.

4.5-year comparison of isolation rates by organisma

| Organism(s) | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of total | n | % of total | n | % of total | n | % of total | n | |

| Candida albicans | 69.74 | 16,473 | 66.86 | 14,648 | 66.00 | 7,936 | 63.00 | 13,930 |

| Candida glabrata | 10.47 | 2,474 | 9.33 | 2,045 | 9.27 | 1,115 | 10.76 | 2,379 |

| Candida tropicalis | 4.38 | 1,035 | 5.09 | 1,114 | 7.01 | 843 | 7.19 | 1,590 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 4.04 | 955 | 4.69 | 1,028 | 5.40 | 649 | 6.41 | 1,418 |

| Candida species | 3.76 | 889 | 5.74 | 1,257 | 3.63 | 437 | 3.24 | 717 |

| Candida krusei | 1.57 | 372 | 2.09 | 457 | 3.14 | 377 | 2.41 | 533 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | 1.16 | 275 | 1.52 | 334 | 0.66 | 79 | 1.40 | 310 |

| Other yeasts | 3.07 | 725 | 1.73 | 379 | 0.51 | 61 | 1.14 | 258 |

| Candida guilliermondii | 0.47 | 111 | 0.77 | 168 | 0.72 | 86 | 0.74 | 163 |

| Candida rugosa | 0.03 | 7 | 0.03 | 7 | 0.17 | 21 | 0.67 | 149 |

| Candida lusitaniae | 0.49 | 115 | 0.45 | 99 | 0.52 | 62 | 0.55 | 121 |

| Trichosporon sp. | 0.29 | 68 | 0.35 | 77 | 0.57 | 69 | 0.47 | 104 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.48 | 58 | 0.40 | 89 | ||||

| Candida kefyr | 0.14 | 34 | 0.38 | 83 | 0.53 | 64 | 0.39 | 86 |

| Candida famata | 0.08 | 19 | 0.22 | 49 | 0.43 | 52 | 0.24 | 53 |

| Candida norvegensis | 0.00 | 1 | 0.07 | 9 | 0.14 | 31 | ||

| Trichosporon beigelii/cutaneum | 0.21 | 26 | 0.14 | 30 | ||||

| Candida inconspicua | 0.07 | 9 | 0.13 | 28 | ||||

| Candida zeylanoides | 0.03 | 4 | 0.09 | 19 | ||||

| Blastoschizomyces capitatus | 0.01 | 1 | 0.08 | 17 | ||||

| Candida dubliniensis | 0.01 | 1 | 0.08 | 17 | ||||

| Rhodotorula sp. | 0.14 | 33 | 0.14 | 31 | 0.14 | 17 | 0.07 | 16 |

| Candida lipolytica | 0.06 | 7 | 0.06 | 14 | ||||

| Candida pelliculosa | 0.01 | 1 | 0.06 | 14 | ||||

| Cryptococcus laurentii | 0.01 | 1 | 0.06 | 13 | ||||

| Saccharomyces sp. | 0.15 | 36 | 0.59 | 130 | 0.19 | 23 | 0.05 | 10 |

| Pichia sp. | 0.06 | 7 | 0.02 | 5 | ||||

| Hansenula anomala | 0.08 | 10 | 0.01 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 23,621 | 21,907 | 12,025 | 22,111 | ||||

All specimen types were tested, all locations were in hospitals, and 89 institutions participated.

Fluconazole susceptibility by species.

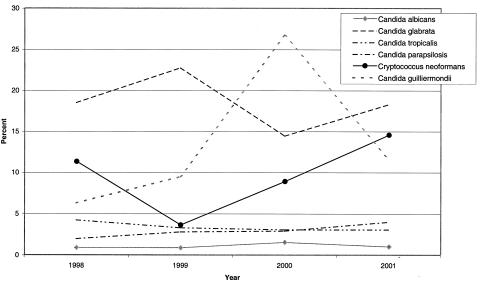

C. parapsilosis was the only species with 20 or more isolates that exhibited a consistent decrease in fluconazole susceptibility over the 4.5-year study period (Table 2), with a relatively small decrease from 98.0 to 96.0%. During this same period, the rate of isolation of C. parapsilosis increased from 4.04 to 6.41% of the total number of isolates. Year-to-year fluconazole susceptibility rate variability was expected over the study period and was evident for some species, including C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. lusitaniae. The percentage of S strains of C. tropicalis appeared to increase, although minimally, during the 4.5-year period, from 95.7 to 96.9%; during this same period, the rate of isolation increased from 4.38 to 7.19% of the total. The fluconazole resistance trends of six yeast species during the study period are shown graphically in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole resistance by organisma

| Organism(s) | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Candida albicans | 0.8 | 16,473 | 0.8 | 14,648 | 1.5 | 7,936 | 1.0 | 13,930 |

| Candida glabrata | 18.5 | 2,474 | 22.8 | 2,045 | 14.4 | 1,115 | 18.3 | 2,379 |

| Candida tropicalis | 4.3 | 1,035 | 3.3 | 1,114 | 3.1 | 843 | 3.1 | 1,590 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 2.0 | 955 | 2.8 | 1,028 | 2.9 | 649 | 4.0 | 1,418 |

| Candida species | 15.6 | 889 | 7.1 | 1,257 | 10.1 | 437 | 9.6 | 717 |

| Candida krusei | 56.5 | 372 | 71.3 | 457 | 68.2 | 377 | 70.2 | 533 |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | 11.3 | 275 | 3.6 | 334 | 8.9 | 79 | 14.5 | 310 |

| Other yeasts | 15.4 | 725 | 18.5 | 379 | 23.0 | 61 | 9.5 | 253 |

| Candida guilliermondii | 6.3 | 111 | 9.5 | 168 | 26.7 | 86 | 11.7 | 163 |

| Candida rugosa | 28.6 | 7 | 14.3 | 7 | 42.9 | 21 | 29.5 | 149 |

| Candida lusitaniae | 2.6 | 115 | 4.0 | 99 | 1.6 | 62 | 6.6 | 121 |

| Trichosporon sp. | 2.9 | 68 | 6.5 | 77 | 5.8 | 69 | 4.8 | 104 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 5.2 | 58 | 10.1 | 89 | ||||

| Candida kefyr | 0.0 | 34 | 4.8 | 83 | 3.1 | 64 | 2.3 | 86 |

| Candida famata | 47.4 | 19 | 10.2 | 49 | 13.5 | 52 | 15.1 | 53 |

| Candida norvegensis | 0.0 | 1 | 55.6 | 9 | 45.2 | 31 | ||

| Trichosporon beigelii/cutaneum | 38.5 | 26 | 26.7 | 30 | ||||

| Candida inconspicua | 55.6 | 9 | 57.1 | 28 | ||||

| Candida zeylanoides | 0.0 | 4 | 52.6 | 19 | ||||

| Blastoschizomyces capitatus | 0.0 | 1 | 11.8 | 17 | ||||

| Candida dubliniensis | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 17 | ||||

| Rhodotorula sp. | 90.9 | 33 | 90.3 | 31 | 94.1 | 17 | 93.8 | 16 |

| Candida lipolytica | 0.0 | 7 | 28.6 | 14 | ||||

| Candida pelliculosa | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 14 | ||||

| Cryptococcus laurentii | 0.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 13 | ||||

| Saccharomyces sp. | 0.0 | 36 | 3.1 | 130 | 4.3 | 28 | 0.0 | 10 |

| Pichia sp. | 14.3 | 7 | 0.0 | 5 | ||||

| Hansenula anomala | 0.0 | 10 | 0.0 | 2 | ||||

| Total | 23,621 | 21,907 | 12,025 | 22,111 | ||||

All specimen types were tested, all locations were in hospitals, 89 and institutions participated. N is the total count for that period and organism.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of fluconazole-resistant isolates of the six species most commonly isolated during the 4.5-year study period. With the exception of the year 2000 for C. neoformans, at least 100 isolates of each species were tested in each year.

C. albicans susceptibility by country, patient location, and specimen type.

In countries with at least 20 C. albicans isolates each year, no increase in relative resistance was evident (Table 3). The proportion of fluconazole-susceptible C. albicans isolates appeared to decrease, although only minimally, over the 4.5 years in hospital general medicine units (from 99.7 to 98.8%) and medical ICUs (from 99.6 to 99.0%) (Table 4). Resistant yeast isolates were most often associated with specimens from the respiratory tract and miscellaneous or other sites and less often seen in blood, genital tract, and biliary tract samples (Table 5). Respiratory and unspecified sites were the most common specimen types from which C. albicans was isolated. The percentage of resistant isolates from respiratory tract specimens was not disproportionate (i.e., not more than twofold higher) compared to that of resistant isolates from all sites (data not shown). Within the general medicine unit locations, 31.4% of all resistant isolates were obtained from miscellaneous or other specimens. When examined for overall rates of fluconazole-susceptible C. albicans by location of the source patient in the hospital, the neonatal ICU (NICU) was the only location that showed a disproportionately lower susceptibility rate in 2000 (95.9%) and 2001 (97.1%), relative to the 100% susceptibility reported in 1997 to 1999 (Table 4). No one specimen type appeared more likely than others to yield resistant yeast isolates in 2001 (Table 5).

TABLE 3.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans by countrya

| Country (no. of sites) | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Argentina (3) | 1.1 | 183 | 2.3 | 172 | 1.4 | 74 | 1.6 | 607 |

| Australia (2) | 17.6 | 102 | 5.9 | 101 | 9.5 | 21 | ||

| Belgium (3) | 0.1 | 824 | 0.5 | 566 | 0.3 | 300 | 0.0 | 450 |

| Brazil (2) | 0.0 | 44 | 1.4 | 517 | 5.3 | 475 | 0.0 | 446 |

| Canada (2) | 0.0 | 87 | ||||||

| China (2) | 2.3 | 86 | 9.8 | 41 | 1.8 | 113 | 2.2 | 93 |

| Colombia (2) | 1.9 | 52 | 1.0 | 102 | 1.8 | 390 | ||

| Czech Republic (2) | 1.0 | 308 | 0.5 | 836 | 0.5 | 985 | 0.2 | 938 |

| Ecuador (1) | 3.8 | 52 | 11.0 | 210 | 7.6 | 250 | ||

| France (4) | 1.2 | 86 | 1.2 | 170 | 2.5 | 204 | 0.9 | 456 |

| Germany (6) | 5.0 | 80 | 1.0 | 102 | 0.0 | 19 | 0.3 | 299 |

| Greece (1) | 9.0 | 67 | 2.8 | 109 | 3.6 | 138 | 2.3 | 88 |

| Hungary (5) | 2.3 | 521 | 2.2 | 501 | 1.8 | 1,016 | ||

| Italy (7) | 1.9 | 1,009 | 1.1 | 696 | ||||

| Japan (1) | 0.0 | 4 | ||||||

| Malaysia (1) | 0.0 | 424 | 0.0 | 295 | 0.0 | 619 | 0.2 | 1,246 |

| Mexico (2) | 0.0 | 20 | 0.0 | 46 | 0.0 | 17 | 0.0 | 23 |

| The Netherlands (1) | 1.1 | 2,097 | 0.4 | 1,790 | 1.5 | 1,204 | ||

| Peru (1) | 0.7 | 550 | ||||||

| Poland (1) | 0.0 | 172 | 0.0 | 53 | 0.0 | 47 | 0.0 | 170 |

| Portugal (1) | 15.1 | 126 | 8.9 | 90 | ||||

| Russia (1) | 0.0 | 21 | 0.0 | 21 | 9.1 | 11 | ||

| Singapore (1) | 0.5 | 200 | ||||||

| Slovakia (4) | 0.0 | 349 | 0.0 | 189 | 0.0 | 138 | 0.5 | 391 |

| South Africa (6) | 0.4 | 2,596 | 0.1 | 2,893 | 0.3 | 1,249 | 0.6 | 1,049 |

| South Korea (1) | 0.0 | 439 | 0.7 | 139 | 0.0 | 426 | ||

| Spain (2) | 1.5 | 1,106 | 1.9 | 736 | 0.4 | 774 | 0.9 | 969 |

| Sweden (1) | 1.1 | 358 | 1.4 | 71 | ||||

| Switzerland (2) | 3.1 | 130 | 1.2 | 161 | ||||

| Taiwan (3) | 0.0 | 114 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 399 | ||

| Thailand (2) | 0.0 | 34 | 0.0 | 80 | 0.0 | 19 | 0.8 | 130 |

| Turkey (2) | 3.0 | 67 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.1 | 89 | 1.4 | 141 |

| United Kingdom (4) | 0.2 | 6,406 | 0.7 | 4,422 | 0.4 | 759 | 0.1 | 977 |

| United States (9) | 2.1 | 676 | ||||||

| Venezuela (1) | 16.7 | 30 | 3.7 | 27 | 9.5 | 95 | 1.7 | 120 |

| Total | 0.8 | 16,473 | 0.8 | 14,648 | 1.5 | 7,936 | 1.0 | 13,930 |

All specimen types were tested, all locations were in hospitals, and 89 institutions participated. n is total count for that period and country.

TABLE 4.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans by locationa

| Location (unit) | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Dermatology | 0.0 | 68 | 2.2 | 139 | 0.9 | 113 | 1.2 | 253 |

| Hematology-oncology | 1.3 | 397 | 0.9 | 939 | 2.0 | 395 | 0.8 | 1,063 |

| Medical | 0.3 | 1,040 | 0.3 | 1,797 | 0.8 | 2,369 | 1.2 | 2,818 |

| Medical ICU | 0.4 | 494 | 0.6 | 1,263 | 1.0 | 525 | 1.0 | 1,159 |

| NICU | 0.0 | 62 | 0.0 | 72 | 4.1 | 73 | 2.9 | 140 |

| ObGyn | 1.4 | 699 | 0.9 | 1,069 | 0.3 | 793 | 0.7 | 1,589 |

| Other | 0.9 | 12,505 | 1.3 | 5,873 | 2.5 | 2,515 | 1.0 | 4,597 |

| Outpatient | 0.8 | 473 | 0.5 | 1,470 | 2.1 | 606 | 0.9 | 1,004 |

| Surgical | 1.3 | 239 | 0.0 | 368 | 1.0 | 299 | 0.9 | 861 |

| Surgical ICU | 0.0 | 116 | 0.0 | 247 | 0.5 | 194 | 0.0 | 342 |

| Urology | 0.0 | 380 | 0.1 | 1,411 | 0.0 | 54 | 1.0 | 104 |

| Total | 0.8 | 16,473 | 0.8 | 14,648 | 1.5 | 7,936 | 1.0 | 13,930 |

All specimen types were tested, and 89 institutions participated. n is the total count for that period and location.

TABLE 5.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans by specimen typea

| Specimen type | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Biliary tract | 0.0 | 74 | 0.0 | 24 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 35 |

| Blood | 0.0 | 480 | 1.3 | 399 | 1.9 | 270 | 0.5 | 836 |

| CSFb | 0.0 | 12 | 0.0 | 12 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.0 | 39 |

| Genital | 0.5 | 610 | 0.4 | 984 | 0.8 | 2,208 | 0.6 | 3,382 |

| Lower G.I.c tract | 0.2 | 1,088 | 1.7 | 709 | 2.6 | 232 | 1.8 | 379 |

| Lower respiratory tract | 0.7 | 3,170 | 0.9 | 2,772 | 0.9 | 1,892 | 1.1 | 2,564 |

| Miscellaneous/other | 1.1 | 6,870 | 0.6 | 5,985 | 3.4 | 1,062 | 1.2 | 2,307 |

| Miscellaneous/fluids | 1.3 | 238 | 1.6 | 251 | 1.0 | 101 | 0.8 | 368 |

| Skin/soft tissue | 0.6 | 505 | 0.2 | 412 | 2.7 | 376 | 1.1 | 718 |

| Upper respiratory tract | 1.3 | 1,628 | 1.9 | 1,710 | 1.4 | 1,024 | 1.5 | 1,870 |

| Urinary tract | 0.6 | 1,803 | 0.3 | 1,390 | 1.4 | 760 | 0.8 | 1,432 |

| Total | 0.8 | 16,473 | 0.8 | 14,648 | 1.5 | 7,936 | 1.0 | 13,930 |

All locations were in hospitals and 89 institutions participated. n is the total count for that period and specimen type.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

G.I., gastrointestinal.

Distribution of fluconazole-susceptible C. albicans in genital isolates by country.

Fluconazole and other azoles are commonly used for the treatment of genital candidiasis, which is most frequently caused by C. albicans (23). Diminished susceptibility is therefore likely to be recognized first in genital source isolates. In countries from which 4.5-year data were available, there was no obvious trend toward reduced fluconazole susceptibility of C. albicans isolates (Table 6). Susceptibility rates in 2001 were generally high (>99%), but several countries (although with low total numbers of isolates tested), including Ecuador, Argentina, and Hungary, had minimally lower rates.

TABLE 6.

4.5-year comparison, by country, of fluconazole-resistant genital isolates of C. albicansa

| Country | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Argentina | 20.0 | 5 | 6.3 | 16 | 2.5 | 80 | ||

| Australia | 0.0 | 2 | ||||||

| Belgium | 0.0 | 8 | 0.0 | 15 | 1.4 | 74 | 0.0 | 157 |

| Brazil | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 74 | ||||

| China | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 13 | ||||

| Colombia | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.0 | 28 | ||

| Czech Republic | 0.0 | 6 | 1.3 | 152 | 0.4 | 240 | 0.0 | 130 |

| Ecuador | 0.0 | 6 | 33.3 | 21 | 5.1 | 39 | ||

| France | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.7 | 116 | 0.0 | 60 |

| Germany | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 68 |

| Greece | 0.0 | 31 | 0.0 | 26 | 0.0 | 12 | ||

| Hungary | 0.0 | 81 | 0.0 | 78 | 2.8 | 360 | ||

| Italy | 1.3 | 306 | 0.0 | 181 | ||||

| Malaysia | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 142 | 0.0 | 434 | 0.0 | 785 |

| Mexico | 0.0 | 1 | ||||||

| The Netherlands | 0.0 | 78 | 0.9 | 113 | ||||

| Poland | 0.0 | 15 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 4 | ||

| Russia | 0.0 | 11 | 0.0 | 5 | ||||

| Singapore | 0.0 | 30 | ||||||

| Slovakia | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 35 | ||||

| South Africa | 0.5 | 189 | 0.0 | 243 | 0.0 | 43 | 0.0 | 153 |

| South Korea | 0.0 | 14 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 7 | ||

| Spain | 1.2 | 163 | 0.8 | 121 | 0.3 | 294 | 0.8 | 367 |

| Sweden | 0.0 | 4 | ||||||

| Switzerland | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 8 | ||||

| Taiwan | 0.0 | 3 | ||||||

| Turkey | 0.0 | 1 | ||||||

| United Kingdom | 0.0 | 171 | 0.0 | 81 | 0.2 | 534 | 0.2 | 622 |

| United States | 0.0 | 25 | ||||||

| Venezuela | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 52 | ||||

| Total | 610 | 984 | 2,208 | 3,382 | ||||

Genital isolates only were tested, all locations were in hospitals, and 89 institutions participated. n is the total count for that period and country.

Yearly change in fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata by patient location and specimen type.

As noted above, the overall resistance of C. glabrata did not show a steady increase but fluctuated. No specific patient location with more than 20 isolates per year showed a steady increase in the percentage of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata (Table 7). Two locations, obstetrics-gynecology (ObGyn) units and surgical ICUs, however, each had at least a twofold increase in resistant C. glabrata in 2001 compared to all other years. Additional surveillance years are needed to see if these increases will be maintained. Only two specimen types for which more than 20 isolates were available per year, bloodstream and upper respiratory tract specimens, were associated with increases in the percentage of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata isolates for the last 2 years of the study versus the first 2.5 years (Table 8).

TABLE 7.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata by locationa

| Location (unit) | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Dermatology | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 8 | 10.0 | 10 | 4.8 | 21 |

| Hematology-oncology | 4.9 | 103 | 16.7 | 192 | 20.6 | 63 | 16.8 | 190 |

| Medical | 41.4 | 186 | 30.2 | 324 | 14.8 | 257 | 18.2 | 461 |

| Medical ICU | 31.5 | 111 | 24.9 | 217 | 15.4 | 91 | 14.0 | 228 |

| NICU | 90.9 | 11 | 50.0 | 22 | 28.6 | 7 | 45.8 | 48 |

| ObGyn | 7.3 | 137 | 8.6 | 187 | 7.6 | 118 | 38.9 | 208 |

| Other | 16.6 | 1,768 | 21.4 | 754 | 15.1 | 358 | 13.7 | 819 |

| Outpatient | 16.3 | 49 | 32.9 | 155 | 14.6 | 128 | 14.5 | 131 |

| Surgical | 14.8 | 54 | 16.2 | 74 | 17.1 | 35 | 16.5 | 170 |

| Surgical ICU | 18.5 | 27 | 13.3 | 45 | 12.2 | 41 | 25.9 | 85 |

| Urology | 23.1 | 26 | 37.3 | 67 | 8.3 | 12 | 16.7 | 18 |

| Total | 2,474 | 2,045 | 1,115 | 2,379 | ||||

All specimen types were tested, and 89 institutions participated. n is the total count for that period and location.

TABLE 8.

4.5-year comparison of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata by specimen typelegend

| Specimen type | 1997-1998 data

|

1999 data

|

2000 data

|

2001 data

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | % R | n | |

| Billary tract | 0.0 | 16 | 0.0 | 5 | 38.5 | 13 | ||

| Blood | 13.1 | 168 | 15.8 | 95 | 22.9 | 70 | 17.8 | 259 |

| CSFb | 100.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 3 | 100.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 1 |

| Genital | 10.9 | 110 | 9.0 | 188 | 10.6 | 311 | 30.7 | 437 |

| Lower G.I.c tract | 8.4 | 154 | 10.3 | 97 | 10.5 | 57 | 12.2 | 98 |

| Lower respiratory tract | 25.3 | 297 | 29.6 | 321 | 18.2 | 159 | 20.8 | 274 |

| Miscellaneous/other | 18.1 | 812 | 25.3 | 671 | 15.3 | 98 | 14.0 | 386 |

| Miscellaneous fluids | 10.2 | 59 | 20.0 | 35 | 23.5 | 17 | 15.3 | 85 |

| Skin/soft tissue | 20.5 | 73 | 23.2 | 69 | 23.5 | 34 | 13.6 | 108 |

| Upper respiratory tract | 10.3 | 195 | 11.8 | 169 | 12.7 | 118 | 17.3 | 248 |

| Urinary tract | 25.0 | 589 | 29.6 | 392 | 13.6 | 250 | 12.2 | 475 |

| Total | 2,474 | 2,045 | 1,115 | 2,379 | ||||

aAll locations were in hospitals, and 89 institutions participated. n is the total count for that period and specimen type.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

G.I., gastrointestinal.

Voriconazole versus fluconazole disk QC in 2001.

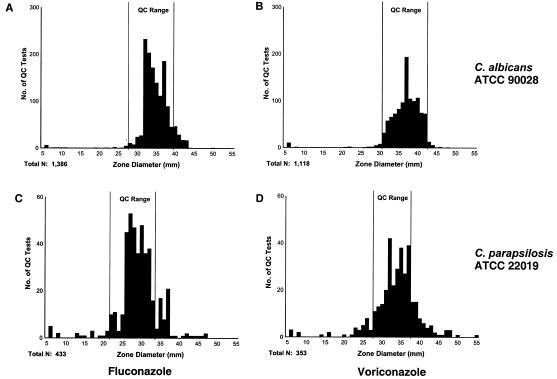

C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used as QC strains for fluconazole and voriconazole disk testing. 2001 was the first year for inclusion of voriconazole and thus the first for which the reliability of QC isolates with voriconazole was as good as that established for fluconazole. More than 90% of all QC tests for C. albicans ATCC 90028 fell within the acceptable-performance ranges for fluconazole (90%) and voriconazole (95%) and yielded normal distributions. Fluconazole QC test results obtained with C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were not as tightly clustered as those obtained with C. albicans ATCC 90028, with only 82% of the tests within the acceptable-performance range. Only 72% of the voriconazole QC test results with C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were within the acceptable QC performance range (28 to 37 mm), primarily because of the number of zone readings of ≥38 mm. Although QC readings showed a bell-shaped distribution, this was not within the QC performance range recommended by the study involving eight expert laboratories presented to the NCCLS (S. Brown et al., 2002 data on file). Out-of-range QC test results obtained with C. parapsilosis were more likely to be above the range for both fluconazole and voriconazole (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of zone sizes obtained with the QC isolates of C. albicans ATCC 90028 (A and B) and C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 (C and D) tested against fluconazole (A and C) and voriconazole (B and D). The reference acceptable-performance ranges for fluconazole and voriconazole are 28 to 39 and 31 to 452 mm, respectively, when tested with C. albicans and 22 to 33 and 28 to 37 mm, respectively, when tested with C. parapsilosis. C. parapsilosis was more often than C. albicans not with the QC limits of both antifungal agents. C. albicans was generally with the limits (>90% for fluconazole and >95% for voriconazole).

MIC50 and MIC90 ranges for fluconazole and voriconazole.

Among all of the species of which 20 or more isolates were tested in 2001, only C. krusei and C. inconspicua exhibited MIC50s (MICs for 50% of the isolates tested) greater than the R breakpoint of ≥64 μg/ml for fluconazole. The fluconazole MIC50s and MIC90s for C. albicans were within the S breakpoint of ≤8 μg/ml. For C. glabrata isolates (n = 2,379), the fluconazole MIC50 of 10.6 μg/ml is in the S-DD category, while the MIC90 was >165 μg/ml, well above the R breakpoint.

No country had C. albicans isolates with fluconazole MIC50s higher than the S breakpoint, but five countries (Australia, Colombia, Ecuador, Hungary, and Russia) had populations with MIC90s of greater than 8 μg/ml (Table 9). The MIC90s for Australia and Russia, however, were based on only 21 and 11 isolates, respectively, and may represent sample bias.

TABLE 9.

Fluconazole and voriconazole agar disk gradient MICs for C. albicansa

| Country (no. of sites in 2001) | Fluconazole

|

Voriconazole

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50 | MIC90 | n | MIC50 | MIC90 | n | |

| Argentina (2) | 0.32 | 1.84 | 607 | 0.019 | 0.128 | 471 |

| Australia (1) | 0.53 | 64.98 | 21 | 0.019 | 0.789 | 21 |

| Belgium (2) | <0.25 | 0.68 | 450 | <0.008 | 0.040 | 372 |

| Brazil (1) | <0.25 | 1.44 | 446 | <0.008 | 0.061 | 333 |

| Canada (2) | 0.41 | 1.12 | 87 | 0.019 | 0.085 | 87 |

| China (2) | 0.87 | 3.90 | 93 | 0.053 | 0.196 | 92 |

| Colombia (2) | 1.44 | 10.58 | 390 | 0.082 | 1.118 | 369 |

| Czech Republic (2) | 0.68 | 3.90 | 938 | 0.046 | 0.350 | 720 |

| Ecuador (1) | 2.37 | 42.11 | 250 | 0.096 | >4.80 | 174 |

| France (4) | 0.87 | 3.90 | 456 | 0.046 | 0.262 | 274 |

| Germany (5) | <0.25 | 1.12 | 299 | 0.014 | 0.061 | 299 |

| Greece (1) | <0.25 | 1.28 | 88 | <0.008 | 0.061 | 88 |

| Hungary (5) | 0.87 | 10.58 | 1,016 | 0.061 | 1.496 | 873 |

| Italy (7) | 0.68 | 5.00 | 696 | 0.030 | 0.262 | 696 |

| Malaysia (1) | 0.41 | 3.04 | 1,246 | 0.046 | 0.350 | 521 |

| Mexico (2) | 1.12 | 4.45 | 23 | 0.082 | 1.512 | 18 |

| The Netherlands (1) | 0.32 | 1.12 | 1,204 | 0.014 | 0.061 | 1,204 |

| Poland (1) | 0.41 | 1.12 | 170 | 0.046 | 0.146 | 45 |

| Russia (1) | 3.04 | 91.22 | 11 | 0.061 | 0.262 | 4 |

| Slovakia (4) | 0.87 | 5.00 | 391 | 0.046 | 0.977 | 391 |

| South Africa (5) | 0.41 | 2.37 | 1,049 | 0.019 | 0.109 | 1,010 |

| South Korea (1) | 0.53 | 1.84 | 426 | 0.026 | 0.146 | 347 |

| Spain (2) | 0.41 | 3.04 | 969 | 0.014 | 0.146 | 966 |

| Switzerland (2) | 0.41 | 1.84 | 161 | 0.019 | 0.082 | 161 |

| Taiwan (3) | 1.44 | 6.42 | 399 | 0.082 | 0.625 | 394 |

| Thailand (2) | 0.68 | 2.70 | 130 | 0.034 | 0.262 | 129 |

| Turkey (2) | 0.68 | 3.47 | 141 | 0.046 | 0.350 | 111 |

| United Kingdom (3) | 0.53 | 3.04 | 977 | 0.019 | 0.146 | 692 |

| United States (9) | 0.53 | 3.04 | 676 | 0.026 | 0.196 | 682 |

| Venezuela (1) | 1.44 | 5.00 | 120 | 0.071 | 0.350 | 98 |

All specimen types were tested, all locations were in hospitals and only 2001 data are shown. Test range: fluconazole, <0.25 to >165 μg/ml; voriconazole, <0.008 to >4.8 μg/ml.

In comparison to those of fluconazole, voriconazole MIC50s for C. albicans were universally less than 0.1 μg/ml (Table 9). Ecuador had the highest voriconazole MIC50 for C. albicans (0.096 μg/ml) (Table 9). Similarly, the highest fluconazole MICs for C. albicans were noted in Ecuador, suggesting cross-resistance. However, the voriconazole MIC50 of 0.096 μg/ml is well within the range of voriconazole concentrations pharmacologically achievable in plasma. However, the fluconazole and voriconazole data from Ecuador were from only one hospital. The highest voriconazole MIC90 for C. albicans isolates was 1.5 μg/ml from both Hungary and Mexico. The species with the highest voriconazole MIC50s were C. krusei (1.5 μg/ml) and Trichosporon beigelii (1.5 μg/ml), followed by C. inconspicua (0.63 μg/ml) and C. glabrata (0.63 μg/ml). Elevated MIC50s and MIC90s did not appear to be associated with any specimen type or hospital location (data not shown).

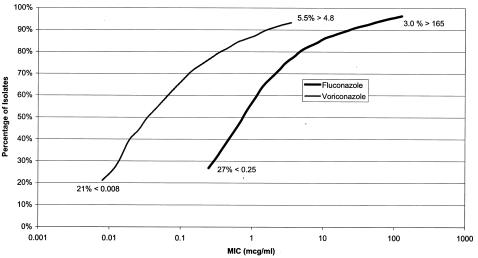

Comparison of fluconazole and voriconazole activities.

Relative to fluconazole, voriconazole demonstrated about 1 to 2 logs greater potency against all of the yeast species combined (Fig. 3), and this observation was consistent for all of the species tested. The greater potency of voriconazole was demonstrated against all species, and five species, C. krusei, Cryptococcus neoformans, C. rugosa, C. norvegensis, and C. inconspicua, demonstrated markedly greater susceptibility to voriconazole than to fluconazole.

FIG. 3.

Cumulative susceptibility of yeast isolates to fluconazole and voriconazole based on all of the organisms tested in the year 2001 (22,111 isolates for fluconazole and 18,569 isolates for voriconazole).

DISCUSSION

A simple, automated disk diffusion test plate reader system, the BIOMIC, was used to facilitate consistent, accurate reading, interpretation, and recording of QC and isolate test results. Quantitative quality-controlled test results were assessed for trends in fluconazole susceptibility over a 4.5-year period in 35 countries. In this study, QC isolates alone were used to validate the data. While this approach is not as definitive as outside test validation, our data appear to be similar to those obtained by others who conducted less geographically and temporally broad studies (2, 19, 21). In the present study, C. albicans was the yeast most commonly isolated from patient specimens. Despite the widespread use of fluconazole for more than a decade, there was no evidence that C. albicans has developed increased resistance to fluconazole over the 4.5-year study period. C. glabrata, which exhibits less susceptibility to fluconazole and is considered an emerging pathogen (4, 7), also did not exhibit increased resistance with time. Only C. parapsilosis exhibited a consistent trend of decreased fluconazole susceptibility over the study period, from 98 to 96% S. Given that the isolation rate of C. parapsilosis increased from 4.0 to 6.4% of the total number of yeast isolates collected during the study period, that this species is commonly isolated from NICU patients, and that it appears to be emerging as a significant pathogen in immunocompromised individuals (our present data and references 7, 8, 23, and 24), continued global monitoring of this organism may be prudent.

In the countries participating in this study, the rates of susceptibility of C. albicans to fluconazole were similar. One exception was Australia, where only 90.5% of 21 isolates were fluconazole susceptible (i.e., 2 resistant isolates) in 2001. The 2001 data from Australia are, however, from only one institution, and whether they reflect a sample bias, reference testing from other institutions, or the general C. albicans population in Australia requires further investigation.

Fluconazole is widely used to treat non-life-threatening and life-threatening yeast infections and is used in some institutions for prophylaxis in patient populations particularly susceptible to the development of serious yeast infections. Increased usage raises the concern that increased resistance to fluconazole in C. albicans, the most commonly isolated yeast, could occur. In the present study, a decrease in the relative percentage of S C. albicans isolates occurred at three locations: general medicine units, medical ICUs, and NICUs. This is based on a lower overall rate of C. albicans isolation, because most C. albicans infections were likely prevented by successful prophylaxis. Although, in general, a relatively higher proportion of fluconazole-resistant isolates was obtained from respiratory specimens, this specimen type was not more likely than others to contain resistant isolates (Table 5). No specimen type was associated with a disproportionately higher rate of resistant C. albicans. In addition, there was no clear disproportionality in specimen types containing fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata (Table 8).

The two patient care locations with the highest rates of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans were general medicine units and other locations in 2001. However, the relative rate of resistant organisms was not disproportionate to the relative rate of C. albicans isolates from those units. The one unit with a disproportionate rate of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans (3%) was the NICU, with about 1% of the total C. albicans isolates; the reason for this is unclear. Whether the few resistant isolates from the NICU were from hospitals in which fluconazole was used for prophylaxis is unknown. A similar relatively higher rate was observed in 2000, although no resistance was reported in 1997 to 1999. The NICU was also the hospital location with the highest percentage of C. glabrata isolates that were resistant, although the total number of C. glabrata isolates was one-fourth of the total number of C. albicans isolates. A recent study has shown that prophylactic fluconazole therapy of very low birth weight (preterm) newborns during their first 6 weeks of life lowers the likelihood of developing serious yeast infections (8). If this approach to prophylaxis becomes a standard of care, these NICU infection patterns should be carefully monitored.

Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of the automated image analysis plate reader system (BIOMIC) for assessment of fluconazole and other disk susceptibilities (9, 12). This automated system provides a reproducible electronic means of assessing the in vitro susceptibility of yeast isolates. The agar disk diffusion method used in this study uses a 0.5 McFarland turbidity inoculum standard and incubation at 35°C for 18 to 24 h, as in bacterial testing. However, Mueller-Hinton agar was supplemented with 2% glucose and 0.5 μg of methylene blue per ml (1, 2, 9, 12). The NCCLS Antifungal Subcommittee formally endorsed this new method in January 2003, but with an incubation time of 20 to 24 h. Publication of document M44-P is scheduled for 2003. The QC results obtained during 2001 support the reproducibility of this system for fluconazole susceptibility testing. Unlike previous years of the study, voriconazole, a recent FDA- and European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical Products-approved triazole, was also tested in 2001. QC results demonstrated good reproducibility with the C. albicans ATCC 90028 reference strain. Greater variation was observed with C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019. Either the acceptable-performance range(s) will require adjustment, or laboratories will need to learn to read the zones more conservatively, i.e., as smaller.

The results of this study demonstrate that both voriconazole and fluconazole exhibit potent in vitro activity against most clinical yeast species. Voriconazole demonstrated markedly enhanced activity, with 10- to 100-fold lower MICs, similar to the observations of others (18, 19). Voriconazole also appears to be more active in vitro than fluconazole for several species considered less susceptible to fluconazole (15), namely, C. krusei, C. norvegensis, and C. inconspicua. Isolates of another fluconazole-resistant species, T. beigelii, exhibited similar rates of susceptibility to voriconazole and fluconazole, with approximately 65% of the isolates testing S. In contrast, all isolates that were members of the basidiomycetous yeast genus Rhodotorula were relatively resistant to both voriconazole and fluconazole. Voriconazole also appeared to be significantly more active than fluconazole against C. rugosa and C. neoformans. These results suggest that voriconazole may be effective for treating infections caused by several species of yeasts considered inherently resistant to fluconazole. Despite the availability of only 1 year of voriconazole data, these results suggest that fluconazole use has not led to the development or selection of azole-resistant species.

A recent study by Pfaller et al. (17) reported results from susceptibility tests of a collection of selected sterile body site yeast isolates from many of these same ARTEMIS study sites; those isolates were tested by the NCCLS broth microdilution, Etest, and NCCLS disk diffusion methods at one reference laboratory. A comparison of the cumulative fluconazole and voriconazole MICs reported in both studies by three methods showed a high correlation. The few and relatively small differences may be attributed to the fact that the Pfaller study reported on only isolates from sterile body sites, whereas this study reports on isolates obtained from all body sites. A more in-depth comparison of results from these two studies is in progress.

The collection and annual analysis of quantitative well-controlled in vitro susceptibility test data to assess trends and patterns in antifungal activity helps to assess whether particular antifungal agents are becoming less useful for the treatment of infections with specific yeast species. Our data demonstrate that, on a global scale, fluconazole susceptibility among different yeast species remained generally the same over the 4.5-year study period and that voriconazole is indeed an extended-spectrum triazole with increased in vitro activity versus Candida species. Voriconazole may prove to be a valuable alternative agent for the treatment of infections with Candida spp., including several species considered to be less susceptible to fluconazole.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Group, New York, N.Y.

The Global Antifungal Surveillance Group in 2001 included the following: Nora Tiraboschi, Hospital Escuela Gral, and Jorge Finquelievich, Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina; David Ellis, Women's and Children's Hospital, North Adelaide, Australia; Dominique Frameree, CHU de Jumet, Charleroi, and Anne Marie Van Den Abeele, St Lucas Campus Heilige Familie, Ghent, Belgium; Arnaldo Colombo, Escola Paulista de Medicina, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Robert Rennie, University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta, and Steve Sanche, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada; Hu Bijie, Zhong Shan Hospital, Shanghai, and Yingchun Xu, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China; Angela Restrepo and Catalina de Bedout, Corporacion para Investigaciones Biologicas, Medellin, and Ricardo Vega and Matilde Mendez, Hospital Militar Central, Bogota, Colombia; Nada Mallatova, Hospital Ceske Budejovice, Ceske, and Stanislava Dobiasova, Reg Institute of Hygiene, Ostrava, Czech Republic; Julio Ayabaca, Hospital Militar FF, AA-Nro. 1, Quito, Ecuador; Michele Mallie, Faculté de Pharmacie, Montpellier, E. Candolfi, Institut de Parasitologie, Strasbourg, J. P. Sequela and M. D. Linas, Hopital de Rangueil, Toulouse, and Bertrand Dupont, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France; I. Braveny, Technische Universität München, Munich, G. Haase, Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen, Aachen, Arne Rodloff, Institut für Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Leipzig, W. Bar, Carl-Thieme Klinikum, Cottbus, and U. Gobel, Charite, Berlin, Germany; George Petrikos, Laikon General Hospital, Goudi, Greece; Erzsebet Puskas, ANTSZ BAZ Megyei Intezete, Miskolc, Mestyan Gyula, Medical University of Pecs, Pecs, Nagy Erzsébet, Albert Szent-Györgyi Medical University, Szeged, and Barcs István, Bajcsy Korhaz, and M. Konkoly-Thege, Johan Bela Institute, Budapest, Hungary; Vivian Tullio, Università degli Studi di Torino, Turin, Domenico D'Antonio, Pescara Civil Hospital, Pescara, Giorgio Scalise, Instituto di Malattie Infettive, Torrette (Ancona), G. C. Schito, University of Genoa, Genoa, G. Fortina, Ospedale di Novara, Novara, and Gian Piero Testore, Ospedale S. Eugenio, and Pietro Martino, Dip di Biotecnologie Cellulari ed Ematologia, Rome, Italy; Kyung-Won Lee, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea; Ng Kee Peng, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Mussaret Zaidi, Hospital General O'Horan, Merida, and Celia Alpuche and Jose Santos, Hospital General de Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico; Jacques F. G. M. Meis, University Hospital Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Danuta Dzierzanowska, Children's Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland; Leonid Stratchounski, Smolensk Medical Academy, Smolensk, Russia; Leon Langsadl, Holy Cross Hospital, Jan Trupl, National Cancer Center, Alena Vaculikova, Derer University Hospital, and Hupkova Helena, St. Cyril and Metod Hospital, Bratislava, Slovak Republic; Denise Roditi, Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, Anwar Hoosen, Ga-Rankuwa Hospital, Medunsa, Janse van Rensburg, Pelanomi Hospital, Bloemfontein, and Heather H. Crewe-Brown, Baragwanath Hospital, and Tiri Towindo, Johannesburg General Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa; Margarita Garau and Amalia del Palacio, Hospital 12 De Octobre, and M. Elena Alvarez and Aurora Sanchez-Sousa, Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain; Jacques Bille, Institute of Microbiology CHUV, Lausanne, and K. Muhlethaler, Universität Bern, Bern, Switzerland; Shan-Chwen Chang, National Taiwan University Hospital, and Hkwok-Woon Yu, VGH-TPE, Taipei, and Jen-Hsien Wang, China Medical College Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; Prasit Tharavichitkul, Chiang-Mai University Hospital, Chiang-Mai, and Malai Vorachit, Ramathibodi Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand; Volkan Korten, Marmara Medical School Hospital, Istanbul, and Deniz Gur, Hacettepe University-Children's Hospital, Ankara, Turkey; Northallerton, Friarage Hospital, Nigel Weightman; Ian M. Gould, Aberdeen Royal Hospital, Aberdeen, and Ruth Ashbee, General Infirmary, Public Health Laboratory Service, Leeds, United Kingdom; Davise Larone, Cornell Medical Center, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Stephen Jenkins, Mt. Sinai Medical Center, New York, and Vishnu Chaturvedi, New York State Department of Health, Albany, Ellen Jo Baron, Stanford Hospital and Clinics, Stanford, and Janet Hindler, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, Calif., Mike Rinaldi, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, Jack Sobel, Harper Hospital, Wayne State University, Detroit, Mich., Mahmoud A. Ghannoum, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio, and Kevin Hazen, University of Virginia, Charlottesville; and Axel Santiago, Hospital Universitario de Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry, A., and S. Brown. 1996. Fluconazole disk diffusion procedure for determining susceptibility of Candida species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2154-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bille, J., and M. P. Glauser. 1997. Evaluation of the susceptibility of pathogenic Candida species to fluconazole. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:924-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chryssanthou, E., and M. Cuenca-Estrella. 2002. Comparison of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing proposed standard and the E-test with the NCCLS broth microdilution method for voriconazole and caspofungin susceptibility testing of yeast species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3841-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidel, P. L., Jr., J. A. Vazquez, and J. D. Sobel. 1999. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:80-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florea, N. R., J. L. Kuti, and R. Quintiliani. 2002. Voriconazole: a novel azole antifungal. Formulary 37:387-398. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant, S. M., and S. P. Clissold. 1990. Fluconazole: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs 39(6):877-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazen, K. C. 1995. New and emerging yeast pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman, D., R. Boyle, K. C. Hazen, J. T. Patrie, M. Robinson, and L. G. Donowitz. 2001. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1660-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebowitz, L. D., H. R. Ashbee, E. G. V. Evans, Y. Chong, N. Mallatova, M. Zaidi, D. Gibbs, and G. A. S. Group. 2001. A two year global evaluation of the susceptibility of Candida species to fluconazole by disk diffusion. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 40:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lozano-Chiu, M., S. Arikan, V. L. Paetznick, E. J. Anaissie, and J. H. Rex. 1999. Optimizing voriconazole susceptibility testing of Candida: effects of incubation time, endpoint rule, species of Candida, and level of fluconazole susceptibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2755-2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marr, K. A., K. Seidel, T. C. White, and R. A. Bowden. 2000. Candidemia in allogeneic blood and marrow transplant recipients: evolution of risk factors after the adoption of prophylactic fluconazole. J. Infect. Dis. 181:309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meis, J. F. G. M., M. Petrou, J. Bille, D. Ellis, D. Gibbs, and The Global Antifungal Surveillance Group. 2000. A global evaluation of the susceptibility of Candida species to fluconazole by disk diffusion. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NCCLS. 1999. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; ninth supplement to the M2-A6, M100-S9. NCCLS, Villanova, Pa.

- 14.NCCLS. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard. NCCLS document M27-A. NCCLS, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Nho, S., M. J. Anderson, C. B. Moore, and D. W. Denning. 1997. Species differentiation by internally transcribed spacer PCR and HhaI digestion of fluconazole-resistant Candida krusei, Candida inconspicua, and Candida norvegensis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1036-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, L. Boyken, S. A. Messer, S. Tendolkar, and R. J. Hollis. 2003. Evaluation of the Etest and disk diffusion methods for determining susceptibilities of 235 bloodstream isolates of Candida glabrata to fluconazole and voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1875-1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, and R. J. Hollis. 2003. Activities of fluconazole and voriconazole against 1,586 recent clinical isolates of Candida species determined by broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and Etest methods: report from the ARTEMIS Global Antifungal Susceptibility Program, 2001. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1440-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, and R. N. Jones. 2003. In vitro activities of voriconazole, posaconazole, and four licensed systemic antifungal agents against Candida species infrequently isolated from blood. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:78-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and D. J. Diekema. 2002. In vitro activities of ravuconazole and voriconazole compared with those of four approved systemic antifungal agents against 6,970 clinical isolates of Candida spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1723-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, J. N. Galgiani, M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, M. Lancaster, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinaldi, T. J. Walsh, and A. L. Barry. 1997. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rex, J. H., M. G. Rinaldi, and M. A. Pfaller. 1995. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saiman, L., E. Ludington, M. A. Pfaller, S. Rangel-Frausto, R. T. Wiblin, J. Dawson, H. M. Blumberg, J. E. Patterson, M. G. Rinaldi, J. E. Edwards, R. P. Wenzel, W. Jarvis, and The National Epidemiology of Mycosis Survey Study Group. 2000. Risk factors for candidemia in neonatal intensive care unit patients. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobel, J. D. 1993. Genital candidiasis, p. 225-247. In G. P. Bodey (ed.), Candidiasis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment, 2nd ed. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Vanden Bossche, H., F. Dromer, I. Improvisi, M. Lozano-Chiu, J. H. Rex, and D. Sanglard. 1998. Antifungal drug resistance in pathogenic fungi. Med. Mycol. 36(Suppl. 1):119-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]