Abstract

Africa shares a unique relationship with maize (Zea mays). After its introduction from New World explorers, maize was quickly adopted as the cornerstone of local cuisine, especially in sub-Saharan countries. Although maize provides macro- and micronutrients required for humans, it lacks adequate amounts of the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan. For those consuming >50% of their daily energy from maize, pandemic protein malnutrition may exist. Severe protein and energy malnutrition increases susceptibility to life-threatening diseases such as tuberculosis and gastroenteritis. A nutritionally superior maize cultivar named quality protein maize (QPM) represents nearly one-half century of research dedicated to malnutrition eradication. Compared with traditional maize types, QPM has twice the amount of lysine and tryptophan, as well as protein bioavailability that rivals milk casein. Animal and human studies suggest that substituting QPM for common maize results in improved health. However, QPM’s practical contribution to maize-subsisting populations remains unresolved. Herein, total protein and essential amino acid requirements recommended by the WHO and the Institute of Medicine were applied to estimate QPM target intake levels for young children and adults, and these were compared with mean daily maize intakes by African country. The comparisons revealed that ∼100 g QPM is required for children to maintain adequacy of lysine, the most limiting amino acid, and nearly 500 g is required for adults. This represents a 40% reduction in maize intake relative to common maize to meet protein requirements. The importance of maize in Africa underlines the potential for QPM to assist in closing the protein inadequacy gap.

Introduction

Our objective in this review is to propose quality protein maize (QPM)3 as a practical food for alleviating protein malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world that may adopt it. This is explored by briefly summarizing the importance of maize in African cuisine; calculating daily target intake levels of QPM to meet adult and child protein, lysine (Lys), and tryptophan (Trp) requirements; and finally comparing the estimated target intake levels to current maize intake levels in sub-Saharan African countries.

Africa#x2019s maize culture

Maize (Zea mays) is of paramount importance in the diets of many native African populations. Of the 22 countries in the world where maize forms the highest percentage of energy in the national diet, 16 are in Africa (1). Relative to traditional crops such as sorghum and millet, maize is a relatively young staple food in Africa (2). After its introduction from New World explorers in the 16th century (3), maize quickly rooted itself as a main ingredient in local cuisine due to its relatively high grain yield, low labor requirements, and favorable storage characteristics (4). Nearly one-half a millennium later, maize has made a distinct imprint across African landscapes with nearly 95% of harvests used for human consumption (5). Lesotho, Malawi, and Zambia rank as the world’s top 3 maize-subsisting countries, surpassing Mesoamerican countries, where the crop originated (3). Maize’s central role as a staple food in Africa is comparable to that of rice or wheat in Asia, with consumption rates the highest in eastern and southern regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

| Country | Maize intake, g/(capita⋅d) | Maize intake, % daily energy intake | Maize, % daily protein intake | % Maize energy:% animal energy3 |

| Angola | 103.1 | 17.3 | 20.5 | 2.0 |

| Benin | 169.4 | 19.8 | 22.2 | 4.6 |

| Botswana | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Burkina Faso | 151.9 | 17.8 | 15.4 | 3.1 |

| Burundi | 70.0 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 4.6 |

| Cameroon | 121.9 | 16.8 | 17.6 | 3.2 |

| Cape Verde | 99.4 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 0.5 |

| Central African Republic | 89.2 | 14.1 | 16.1 | 1.3 |

| Chad | 33.1 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 0.8 |

| Comoros | 10.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| Congo | 14.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 0.3 |

| Congo, Democratic Republic | 60.8 | 12.5 | 21.7 | 6.1 |

| Côte d‘Ivoire | 43.9 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 1.5 |

| Djibouti | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Equatorial Guinea | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Eritrea | 16.1 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 0.8 |

| Ethiopia | 113.6 | 19.5 | 15.9 | 4.0 |

| Gabon | 45.0 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 0.3 |

| Gambia | 27.2 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 0.5 |

| Ghana | 99.4 | 10.7 | 13.7 | 2.3 |

| Guinea | 25.8 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 0.8 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 46.7 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 1.0 |

| Kenya | 221.7 | 33.3 | 30.7 | 2.4 |

| Lesotho | 437.8 | 55.4 | 52.0 | 9.7 |

| Liberia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Malawi | 359.2 | 51.2 | 52.5 | 17.4 |

| Mali | 66.1 | 7.9 | 7.5 | 0.8 |

| Mauritania | 18.1 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0.1 |

| Mauritius | 7.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Mozambique | 140.0 | 19.5 | 28.2 | 4.8 |

| Namibia | 143.1 | 17.8 | 16.5 | 1.2 |

| Niger | 8.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Nigeria | 69.7 | 8.0 | 9.1 | 2.5 |

| Rwanda | 35.0 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 1.7 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 61.7 | 7.6 | 8.9 | 1.1 |

| Senegal | 71.1 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 1.2 |

| Seychelles | 74.7 | 9.5 | 7.2 | 0.5 |

| Sierra Leone | 16.7 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.6 |

| Somalia | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| South Africa | 288.3 | 29.6 | 28.1 | 2.1 |

| Sudan | 6.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| Swaziland | 166.4 | 24.0 | 23.8 | 2.1 |

| Tanzania, United Republic | 162.2 | 25.7 | 25.3 | 4.8 |

| Togo | 180.0 | 2.5 | 28.6 | 0.7 |

| Uganda | 67.2 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 1.4 |

| Zambia | 320.3 | 51.8 | 54.9 | 10.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 323.1 | 41.2 | 43.8 | 4.9 |

Estimated values calculated from FAO food balance sheets of 2007 (6).

ND, no data available.

Calculated by dividing the ratio (mean daily energy from maize:mean daily energy total) by the ratio (mean daily energy from animal products:mean daily energy total) for each country using FAO food balances sheets of 2007 (6).

Africans plant maize as both a household garden food and cultivated field grain, and it is often referred to as a “woman’s crop,” because females commonly work in the field and do the cooking (3). A small percentage of the crop is eaten as fresh maize, which is boiled or roasted as a snack; kernels are stripped from the cob, dried, and then stored or sold for further processing. The vast majority of maize is harvested at maturity, and the dried kernels are often milled into flour or grits using various wet or dry techniques (7). African food differs from that of other maize-growing regions of the world in that maize-based dishes are most often boiled or cooked as opposed to fried or baked (Table 2). In rural populations, maize flour serves as the raw material for fermented or boiled beverages, thick porridges, and weaning gruel. Thick maize porridge, almost analogous between countries, is traditionally eaten twice daily and is often prided by Africans as their own distinctive dish (8–10).

Table 2.

Traditional maize-based foods by countries around the world1

| Food name | Cooking technique | Country |

| Whole grain | ||

| Hominy | US | |

| Pozole | Mexico | |

| Nixtamal | Central America | |

| Munguçá | Brazil | |

| Boiled porridges | ||

| Atole | Thin, unfermented | Central America |

| Pinole | Mexico | |

| Chicha morada | Brazil | |

| Mingau | Brazil | |

| Canjica | Brazil | |

| Pamonha | Thin, fermented | Brazil |

| Ogi | Nigeria | |

| Uji | Africa | |

| Mahewu | Thick | South Africa |

| Hanchi | South America | |

| Mazamorra | South America | |

| Maizena | Mexico | |

| Humita | South America | |

| Tô, Tuwo, Asida | Africa | |

| Polenta | South America, Europe | |

| Finger bread | Southwestern US | |

| Couscous, Cuzcuz | Steamed | Africa, Brazil |

| Tamales | Latin America | |

| Baked | ||

| Tortillas | Unfermented | Central America |

| Arepas | Columbia, Venezuela | |

| Piki | US (Hopis) | |

| Bivilviki | US (Hopis) | |

| Someviki | US (Hopis) | |

| Cornmeal | US (Hopis) | |

| Roti, Chapati | India | |

| Corn bread | Worldwide | |

| Injera | Fermented | Ethiopia |

| Dough | ||

| Masa | Unfermented | Central America |

| Kenkey | Fermented | Ghana |

| Pozol | Mexico | |

| Alcoholic drinks | ||

| Urawga, Mwenge | Kenya, Uganda | |

| Chicha | South America | |

| Kaffir beer, Chibuko | Southern Africa | |

| Tesguino | Mexico | |

| Pito | Nigeria | |

| Talla | Ethiopia | |

| Busas | Kenya | |

| Opaque beer | Zambia |

Adapted with permission from (7).

Malnutrition in Africa

In the mid 20th century, African agriculture was largely self-sufficient, but around the 1970s, food production began to fall by 1.5% annually while total population expanded at twice that rate (11). Nutrition and food sufficiency have suffered as a result, with declining per capita food consumption, overall energy, and protein intakes in several countries that consume maize as a staple crop (Table 3). According to various demographic and health surveys (1988–1999), low birth weight prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 11 to 52%, stunting (chronic malnutrition) is as high as 40% of children in some areas, and emaciation or wasting (acute malnutrition) affects 10% of children (12).

Table 3.

Changes in maize, energy, and protein consumption in leading maize-eating African countries from 1961 to 20071

| Country, region2 | Year | Maize intake, kg/(capita⋅y) | % Change from previous decade3 | Total energy intake, kcal/(capita⋅y) | % Change from previous decade3 | Total protein intake, g/(capita⋅d) | % Change from previous decade |

| Zimbabwe, Eastern Africa | 2007 | 116.3 | 3.3 | 2238 | 13.8 | 55.9 | 21.8 |

| 1997 | 112.6 | −2.3 | 1966 | −2.4 | 45.9 | −8.6 | |

| 1987 | 115.2 | −17.0 | 2015 | −12.2 | 50.2 | −20.7 | |

| 1977 | 138.8 | 6.5 | 2296 | 2.2 | 63.3 | 2.9 | |

| 1967 | 130.3 | 5.8 | 2246 | 6.9 | 61.5 | −1.1 | |

| 1961 | 123.2 | 2102 | 62.2 | ||||

| Zambia, Eastern Africa | 2007 | 115.3 | −11.4 | 1873 | −2.0 | 46.6 | −4.5 |

| 1997 | 130.2 | −16.1 | 1912 | −6.4 | 48.8 | −7.8 | |

| 1987 | 155.2 | −7.9 | 2042 | −17.2 | 52.9 | −23.0 | |

| 1977 | 168.5 | 13.2 | 2466 | 9.3 | 68.7 | 6.8 | |

| 1967 | 148.8 | −6.6 | 2257 | 2.1 | 64.3 | 1.4 | |

| 1961 | 159.3 | 2211 | 63.4 | ||||

| Malawi, Eastern Africa | 2007 | 129.3 | −1.0 | 2172 | 8.5 | 56.6 | 9.9 |

| 1997 | 130.6 | −13.7 | 2002 | 0.3 | 51.5 | −10.4 | |

| 1987 | 151.4 | −2.3 | 1997 | −15.2 | 57.5 | −17.1 | |

| 1977 | 155 | −9.6 | 2355 | 7.3 | 69.4 | 6.6 | |

| 1967 | 171.5 | 16.3 | 2194 | 9.2 | 65.1 | 8.0 | |

| 1961 | 147.5 | 2009 | 60.3 | ||||

| Lesotho, South Africa | 2007 | 157.6 | 6.1 | 2479 | 2.7 | 69.9 | 4.5 |

| 1997 | 148.5 | −2.1 | 2413 | 6.5 | 66.9 | 4.0 | |

| 1987 | 151.7 | 105.6 | 2266 | −1.1 | 64.3 | −8.4 | |

| 1977 | 73.8 | −20.7 | 2291 | 14.1 | 70.2 | 15.7 | |

| 1967 | 93.1 | 0.1 | 2008 | −0.2 | 60.7 | −5.5 | |

| 1961 | 93 | 2013 | 64.2 |

Values from FAO food balance sheets at various years (6).

Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and Lesotho were chosen as examples of countries that habitually consume large amounts of maize ([≥320 g/(capita⋅d)]. See Table 1.

The columns titled, “% Change from previous decade” reflect increases or decreases of maize, energy, and protein intakes compared to the previously dated year in the row below. All values listed, except for 1961 to 1967, reflect a change over a decade.

Even during the best of economic times, a maize-based diet threatens to impoverish the bodies of those who predominantly subsist on it. Maize supplies many macro- and micronutrients necessary for human metabolic needs; however, it lacks B vitamins and the essential amino acids Lys and Trp. White maize varieties, which are widely preferred in much of Africa, lack provitamin A carotenoids and vitamin A is essential for immunity, growth, and eyesight (7). In addition, some minerals in the maize grain have low bioavailability due to high concentrations of phytate (7). Many sub-Saharan African populations consume >20% of daily energy from maize, with Lesotho, Zambia, and Malawi consuming >50% (Table 1). High-quality protein sources, such as eggs, meat, dairy products, and legumes, provide total or complementary sources of the amino acids limited in maize, but many rural poor have limited access to these foods (13). In fact, higher daily consumption of maize is often associated with lower intakes of animal products (Table 1). Severe protein malnutrition may cause kwashiorkor, which manifests from chronic protein and energy imbalance and increases susceptibility to life-threatening diseases, such as tuberculosis and gastroenteritis (14). Common symptoms of kwashiorkor include swollen abdomens, listlessness, and hair color changes. Kwashiorkor is sometimes called the “weaning disease” because of the onset of symptoms in many young children at the time of dietary shift from breast milk to soft cereal foods (15).

QPM: a new kind of maize

Undernutrition can stem from one or many nutrient deficiencies. Supplementation and fortification programs targeted at improving vitamin A, zinc, or folic acid status are some examples of current nutritional ameliorating efforts (16). Protein deficiency, on the other hand, has been in and out of the international nutrition limelight since the early 1900s. Researchers at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center realized the potential for ameliorating protein malnutrition in maize-dependent populations by using traditional agriculture and nutritionally improved maize cultivars. In the early 1960s, a mutant maize cultivar with similar total protein content but twice the amount of Lys and Trp (17, 18) and 90% bioavailable protein (19) was discovered. This nutritionally superior maize was named opaque-2 maize, after the “opaque-2” single gene mutation responsible for its improved protein quality. Thereafter, efficacy testing in humans and animals was enthusiastically undertaken (20, 21). Subsequent conventional breeding efforts generated numerous cultivars with improved agronomic characteristics, and these were referred to as QPM (22, 23).

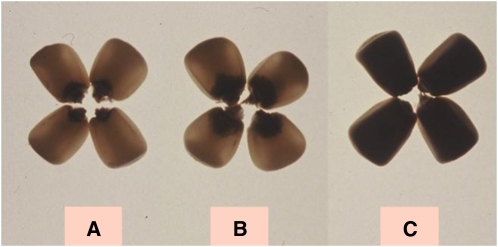

Like its opaque-2 counterpart, QPM is considered a biofortified food, because its nutritional profile has been improved using conventional breeding techniques (Fig. 1). The basic component of both of these maize cultivars is the opaque-2 (sometimes abbreviated o2) mutation. This mutation causes a shift in the synthesis of certain protein types in the endosperm compartment of the maize kernel. Common maize contains nearly 70% endosperm protein as zein, a Lys- and Trp-poor protein body. The opaque-2 mutation suppresses zein synthesis while simultaneously increasing production of other nonzein proteins that are richer sources of Lys and Trp (24, 25). Some studies suggest that QPM can provide nutritional benefits in addition to its protein profile, such as higher niacin bioavailability (26). Other biofortification efforts to improve the protein profile include high-methionine varieties (27).

Figure 1.

Back-lit maize kernels illustrating the phenotypic differences of opaque-2 mutation. Common maize (A); QPM (B); opaque-2 maize without modification of agronomic characteristics (C).

Completed research

Numerous QPM feeding trials have been completed in areas where participants, many times children, are undernourished. A major distinction between early compared to later opaque-2 maize research is that earlier studies focused on children with or recuperating from severe malnutrition, whereas subsequent studies focused on mild or moderately malnourished children. Many limitations related to study design and scarcity of peer-reviewed published products have diluted confidence in their findings in the nutrition community. A recent meta-analysis conducted using 9 community-based studies with children from Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Mexico, and Nicaragua found noteworthy results concluding that consumption of QPM instead of common maize can significantly improve child growth (28). From these studies, there was an average 12% height increase and 9% weight increase in the children eating QPM from baseline to endline compared with those eating common maize. Of these 9 studies, only 2 were peer reviewed at the time of the meta-analysis. Seven additional QPM feeding trials were excluded from the analysis because of difficulties tracking down completed manuscripts and data sets from principal investigators. The positive results of this meta-analysis were supported by earlier research conducted using opaque-2 maize in both children and adults (20). Overall, these studies concluded that consuming opaque-2 maize improves growth rates and nitrogen metabolism, suggesting that it may be as efficacious as consuming milk casein.

Nutrition impact research

Despite nearly one-half century of research, conclusions about QPM’s practical nutritional contributions in African and other maize-subsisting populations remain largely undocumented. Can QPM provide a nutritional advantage for maize monocultures? Although previous feeding trials in humans and animals suggest this, a specified target QPM intake level to meet dietary requirements in the context of existing eating traditions has not been clearly established. For instance, QPM may provide a significant nutritional impact for populations in Lesotho where per capita maize consumption is among the world’s highest; however, what about other parts of Africa?

From the research described above, it appears that QPM has potential to augment healthy growth and protein metabolism in the rural poor who consume maize on a daily basis. To translate research into practical knowledge, 2 major nutritionally charged questions need to be answered: 1) How much QPM must be eaten in order to maximize health benefits? and 2) Are the estimated QPM intake goals realistic? In the prime of Bressani’s (20) opaque-2 research career, he had the same questions in mind. Regression analysis of nitrogen retention values was used from human feeding trials to extrapolate estimated maize intakes required to meet protein needs. Nitrogen balance remains a traditional method for estimating protein metabolism and is calculated as the difference between nitrogen lost in feces and urine from the nitrogen ingested as food. When the value is positive, protein deposition is occurring in the body and an individual is categorized as being protein adequate (29). From Bressani’s calculations, an estimated 23.6 g normal maize/kg body weight (BW) was required to achieve nitrogen equilibrium, whereas only 8.2 g/kg was needed from opaque-2 maize (20). If a child weighed 15 kg, he or she would therefore require ∼120 g/d opaque-2 maize to maintain protein adequacy. This corresponds to 440 kcal (1 kcal = 4.18 kJ), which is much less than daily energy requirements. If this same child were to consume common maize, he or she would require ∼3 times more maize, an amount that far exceeds intake levels in African countries with even the highest adult per capita intakes (Table 1). Further support for a positive role for opaque-2 maize comes from studies showing that supplementation of common maize with both Lys and Trp or soy protein (containing complementary amino acids) was unsuccessful in providing competitive nitrogen retention values (30). For these reasons, opaque-2 maize is acknowledged as a protein source that can enhance protein deposition and provide an improved amino acid profile compared to common maize types.

Protein and amino acid requirements

Daily protein requirements as outlined by the WHO in 2007 suggest 0.66 g protein/(kg BW⋅d) for adults and slightly higher values for children and infants dependent on age (29). For example, a child of 3 y is estimated to require 0.73 g/kg BW/d for growth and maintenance, whereas a child just a year younger requires an estimated 0.79 g/(kg BW⋅d). For indispensible amino acids, 30 mg Lys/(kg BW⋅d) and 4 mg Trp/(kg BW⋅d) are the estimated requirements for adults and upwards of 45 and 6.4 mg/(kg BW⋅d) of Lys and Trp, respectively, for young children. Requirements for Lys and Trp are established in addition to total protein, because they cannot be synthesized de novo in humans and other monogastric animals, with Lys being the most limiting amino acid in maize and other cereals (31). These requirements represent the minimum amount of protein and amino acids that must be supplied in the diet to satisfy metabolic demand and achieve nitrogen equilibrium and do not reflect those of children with special needs (e.g. stunted growth, sickness, or other metabolic stressors). The 2006 Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations for meeting Estimated Average Requirements for children are higher than the WHO’s (Table 4).

Table 4.

IOM and WHO protein and amino acid recommendations for adults and preschool-aged children1

| Group | Protein, g/(kg⋅d) | Lys, mg/(kg⋅d) | Trp, mg/(kg⋅d) | Source | Reference |

| Adult | 0.66 | 30 | 4 | WHO | 29 |

| Adult | 0.66 | 31 | 4 | IOM | 32,332 |

| Child (3 y) | 0.73 | 35 | 4.8 | WHO | 29 |

| Child (1–3 y) | 0.87 | 45 | 6 | IOM | 32,33 |

Estimated target maize intakes

To answer the 2 questions presented earlier, total protein, Lys, and Trp requirements established by both WHO and IOM were used to generate theoretical QPM intake levels to meet dietary needs. Estimated target maize intakes were further compared to traditional maize intake levels by country and region to conclude whether or not QPM may be a practical tool against protein malnutrition in sub-Saharan Africa (Table 5). All final calculations of “target” daily intakes to meet nutrient requirements are assuming maize is the sole source of protein consumed in the diet. Although a maize-exclusive diet is not encouraged, this exercise helps to understand the maximum potential of QPM in both adults and young children. Unfortunately, a maize-exclusive diet is a reality for some. For example, rural children in Africa are many times weaned off breast milk and consume thin, maize-based porridges exclusively (34).

Table 5.

Estimated target daily maize intakes to meet protein and amino acid requirements of a reference adult and child

| Maize type | Nutrient reference | Nutrient | Amount in 100 g maize | Adult requirement/d | Intake to meet requirement, g/d | Child requirement/d | Intake to meet requirement, g/d |

| Common | WHO | Total protein (g) | 9.41 | 462 | 490 | 8.8 | 93 |

| Lys (mg) | 265 | 2100 | 792 | 420 | 158 | ||

| Trp (mg) | 67 | 280 | 418 | 57.6 | 86 | ||

| QPM | WHO | Total protein (g) | 9.8 | 46 | 471 | 8.8 | 89 |

| Lys (mg) | 408 | 2100 | 515 | 420 | 103 | ||

| Trp (mg) | 75 | 280 | 373 | 57.6 | 77 | ||

| Common | IOM | Total protein (g) | 9.4 | 46 | 490 | 10.4 | 111 |

| Lys (mg) | 265 | 2170 | 819 | 540 | 204 | ||

| Trp (mg) | 67 | 280 | 418 | 72 | 107 | ||

| QPM | IOM | Total protein (g) | 9.8 | 46 | 471 | 10.4 | 107 |

| Lys (mg) | 408 | 2170 | 532 | 540 | 132 | ||

| Trp (mg) | 75 | 280 | 373 | 72 | 96 |

Estimated target maize intakes to meet protein, Lys, and Trp requirements gave differences between WHO and IOM reference levels. For children, the IOM requirements resulted in greater QPM target intake levels of ∼20% for total protein, 28% for Lys, and 25% for Trp relative to the WHO requirements, which were calculated by dividing the difference in IOM and WHO “intake to meet requirement” values for protein, Lys, and Trp (Table 5) and then dividing by the IOM respective values × 100. Target maize intake levels were calculated from the WHO and IOM requirements to illustrate the spectrum of estimated maize intakes, because actual nutrient utilization is individualized. It is difficult to draw conclusions about which requirements may be more appropriate for malnourished populations due to the many influential factors on protein needs, such as energy expenditure, catch-up growth, and stress. Calculations reveal that consuming QPM reduced target maize intake estimates by nearly 40% compared to common maize to meet Lys requirements and 20% for Trp. Because Lys is the first limiting amino acid in maize, if enough maize is eaten to achieve Lys adequacy, total protein requirements will be met as well. Eating QPM to meet energy requirements demands the highest maize intakes. Approximately 400 g maize provides 1500 kcal (Table 5). Average daily energy intakes of Africans range from 1860 kcal/(capita⋅d) in Central Africa to 3000 kcal/(capita⋅d) in South Africa (6). The estimated energy requirement calculated for an active 70-kg adult male is ∼3000 kcal/d (35), which would require daily maize intakes > 800 g. These data suggest that despite QPM’s superior protein quality, supplementing daily maize diets with energy-dense foods or side dishes is advised to better satisfy energy demands and to provide dietary diversity for most.

The lowest target maize intake estimate to meet Lys requirements for a 12-kg child is just over 100 g/d based on WHO values (Table 5). Compared with previous research, Bressani’s estimate of 120 g/d opaque-2 maize for a 15-kg child was similarly favorable. This theoretical daily intake range of 100–120 g opaque-2 maize is a realistic suggestion, considering that more than one-third of sub-Saharan countries currently consume per capita maize intakes > 100 g/d (Table 1). Further support comes from recent research in Zambia, where 3- to 5-y-old children (weight 14.8 ± 2.0 kg) were fed 158 g maize over 2 meals daily (36). Two complementary feeding studies performed in young adults estimated that an average nitrogen balance occurred when consuming 250–350 g opaque-2 maize, dependent upon body composition (37). Only six countries evaluated appear to consume maize > 200 g/(capita/d) (Table 1), with Lesotho and Malawi being the only two countries to have estimated intakes > 350 g/(capita⋅d). These results suggest that the inclusion of other protein sources via dietary diversification is essential for achieving protein adequacy in the majority of maize-subsisting countries, but having a dietary foundation of QPM can assist in closing the gap toward protein adequacy.

Protein-adequate populations

Populations that consume maize daily for their energy and protein requirements are obvious target markets for QPM foods. However, would QPM’s nutritionally superior kernels pose risks related to protein toxicity in protein-adequate populations? In developed countries, protein and essential amino acids are not only abundant in typical diets, especially for meat eaters, but consumption is often far in excess (∼4 times greater) of the recommended requirements (29). High-quality protein sources are widely available and often packaged for convenient consumption, including processed products such as yogurt-to-go packets, dried meat jerky snacks, fortified snack bars, and high-protein drinks. There is currently no determined toxic level of protein intake, but rather known side effects that can arise from chronic, extreme protein intakes. For this reason, it is recommended to keep daily protein intake below 1.5 g protein/kg BW, or about 10–35% total energy, to avoid potential long-term health threats related to kidney function, calcium metabolism, cardiovascular disease, and cancer (32). The percent daily energy consumed from maize is typically inversely related to socioeconomic status (38). The highest maize-consuming countries, e.g. Lesotho, Zambia, and Malawi, consume protein within this recommendation (10–11% total energy) (6) while consuming >50% of both daily energy and protein from maize (Table 1). South Africa, with the highest per capita energy consumption, also consumes 11% of its energy from protein, but only 30% of its daily energy and protein from maize (Table 1).

Consuming the target intake levels for QPM to meet Lys requirements (∼500 g QPM for a 70-kg adult and ∼100 g QPM for a 12-kg child) (Table 5) would also pose no risks for protein toxicity. This is determined by multiplying the concentration of QPM protein (9.8 g/100 g) (Table 5) by target QPM intake to meet Lys requirements and dividing by BW. In this scenario, an adult would receive 0.7 g protein/kg BW and a child ∼0.8 g/kg, which is below the maximum intake recommendation of 1.5 g/kg. Because QPM differs only in amino acid content rather than total protein relative to common maize, wealthier African populations like South Africa who would switch to QPM would consume slightly higher amounts of Lys and Trp as an outcome. These individuals are likely to be protein adequate to begin with, suggesting that QPM would have relatively little nutritional impact except to offer a more complete protein. The real diet dangers for protein-adequate individuals are high-fat, high-energy foods consumed in place of traditional maize-based foods, which are known to augment diseases accompanying excess body fat (39).

QPM practicality in the developing world

High-quality protein sources, such as fortified nut paste and milk products, are currently being disseminated across high-risk populations (40). These distribution programs, nonetheless, are limited by their breadth of coverage and require inter-country infrastructure and continuous resources to succeed. For these reasons and others, converting a staple food, like maize, into a more nutritious food as a sustainable approach to improve health deserves extensive consideration. Its seeds can reach remote areas where malnutrition rates are high and provide the rest of the population with a nutritional bonus. Furthermore, studies have provided evidence that the protein fractions in QPM are robust to many traditional processing and cooking techniques (4) and have few detectable differences visually compared to common maize varieties (41). Commercial release of QPM has occurred in a handful of countries, including those in parts of Asia, Central America, and Africa (42). Ghana, located in West Africa, experienced accelerated widespread adoption of QPM after it was introduced in 1989 [reviewed in (3)]. The successes experienced by this country provide a useful example for future targeted QPM dissemination and breeding programs in other countries, which ultimately needs to include desirable agronomic traits to be adopted by farmers.

Future directions for QPM efforts include developing yellow and orange varieties for dissemination (Fig. 2), which contain higher levels of β-carotene and other carotenoids relative to white varieties (7). These high-provitamin A–carotenoid QPM varieties may be nutritionally advantageous for preventing or treating xerophthalmia, night blindness, and mortality related to vitamin A deficiency. Some researchers maintain that increasing protein quality alone may have a synergistic effect on the efficiency of provitamin A carotenoid bioconversion and utilization (43). Vitamin A is one of the top 3 micronutrients often missing in diets of the rural poor (14). Therefore, yellow/orange QPM would have an even greater impact on health and nutrition for target countries such as Africa. A target level of 15 μg β-carotene equivalents/g dry weight has been set by nutritionists for provitamin A biofortification of maize based on calculations that this would provide the estimated average requirement of vitamin A to children who consume 200 g/d dry maize (44). Although recent studies in Central and South Africa suggest that acceptance is likely (45–47), the obvious yellow/orange color of the kernels represents an obstacle for acceptance by consumers accustomed to eating almost exclusively white maize. Food preferences are often modifiable with enough incentive or education. For example, children in rural Zambia were highly receptive to traditional white maize dishes substituted with biofortified orange maize meal (36) and 94% of surveyed Zimbabwean households reported that they would consume yellow maize if they were educated about its superior nutritional qualities over white maize (47).

Figure 2.

QPM varieties are being crossed with high carotenoid varieties and traditionally bred to contain an enhanced overall nutritional profile. Shown are cobs harvested in Mexico.

Along with QPM’s many nutritional advantages, there also remain some challenges for widespread adoption. Some of these, as described by Atlin et al. (4), include the lack of profitable markets for commercial producers, lack of interest among maize food processors in marketing QPM as a premium product, and lack of government incentive to encourage adoption by subsidizing the price of QPM seed. Despite these challenges, the time to explore the possibilities of biofortified maize has never been better. Global demand for maize is expected to multiply in the near future as annual population growth projections exceed 3% (3). Switching from common maize to QPM provides a more balanced protein source relative to common maize without sacrificing energy, yield, and micronutrients or changing native food supply systems (48). QPM is a nutritionally enhanced crop patiently awaiting widespread dissemination and the opportunity exists to realize its potential as a tool for global health improvement.

Conclusion

Sub-Saharan African countries may benefit substantially from QPM implementation because of the high rates of daily maize intake coupled with low intake of balanced-protein foods containing essential amino acids. Estimated target QPM intake levels of 100 g/d for young children and 500 g/d for adults were calculated to meet 100% WHO and IOM protein, Lys, and Trp requirements. With only a handful of countries consuming maize at levels > 300 g/(capita⋅d), dietary diversification with high-energy and complementary protein sources remain important. Making simple dietary substitutions of common maize with QPM can augment intake of a more nutritionally balanced protein source, which, as previous research suggests, can result in measureable health impacts.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Dr. Kevin Pixley (Associate Professor of Agronomy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and CIMMYT, Mexico) for reading this review as a member of the master’s committee. E.T.N. and S.A.T. discussed the direction of the article; E.T.N. drafted the manuscript; and S.A.T. revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by HarvestPlus (contract nos. 8217 and 8202). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of HarvestPlus.

Author disclosures: E. T. Nuss and S. A. Tanumihardjo, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: BW, body weight; IOM, Institute of Medicine; QPM, quality protein maize.

Literature Cited

- 1.Dowswell CR, Paliwal RL, Cantrell RP. Maize in the third world. Boulder (CO): Westview Press; 1996. p. 8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miracle MP. The introduction and spread of maize in Africa. : Maize in tropical Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1966. p. 87–100 [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCann JC. Africa and the world ecology of maize. : Maize and grace: Africa’s encounter with a New World crop, 1500–2000. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 2005. p. 1–22 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atlin GN, Palacios N, Babu R, Das B, Twumasi-Afriyie S, Friesen DK, De Groote H, Vivek B, Pixley KV. Quality protein maize: progress and prospects. In: Janick J, editor. Plant breeding reviews. Vol. 34. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. p. 83–130 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byerlee K, Heisey PW. Evolution of the African maize economy. In: Africa’s emerging maize revolution. Boulder (CO): Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc; 1997. p. 9–22 [Google Scholar]

- 6.FAO of the United States FAOSTAT food balance sheets. Last updated June 2010 [cited July 2010]. Available from: http://faostat.fao.org/site/368/default.aspx# ancor.

- 7.Nuss ET, Tanumihardjo SA. Maize: a paramount staple crop in the context of global nutrition. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010;9:417–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blandino A, Al-Aseeri ME, Pandiella SS, Cantero D, Webb C. Cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res Int. 2003;36:527–43 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jespersen L. Occurrence and taxonomic characteristics of strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae predominant in African indigenous fermented foods and beverages. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;3:191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Food Consumption Survey Children aged 1–9 years, South Africa; Department of Health. Stellenbosch, South Africa [cited July 2010]. Available from: http://www.sahealthinfo.org/nutrition/foodconsumption.htm

- 11.Byerlee K, Eicher CK. Africa’s food crisis. : Africa’s emerging maize revolution. Boulder (CO): Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc; 1997. p. 3–8 [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO The nutritional situation in the African region: challenges and perspectives. Brazzaville (Republic of Congo): Regional Committee for Africa (fifty-fourth session); 2004. p. 1 [Google Scholar]

- 13.NRC Malnutrition and protein quality. : Quality protein maize. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. p. 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolfes SR, Pinna K, Whitney E. Protein: amino acids. : Understanding normal and clinical nutrition. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth; 2009. p. 198 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HJ, Km KH, Park HJ, Lee KH, Lee GH, Choi EJ, Kim JK, Chung HL, Kim WT. A case of lethal kwashiorkor caused by feeding only with cereal grain. Korean J Pediatr. 2008;51:329–34 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micronutrient Initiative and United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund Vitamin and mineral deficiency: a global progress report; 2004 [cited July 2010]. Available from: http://www.micronutrient.org/CMFiles/PubLib/VMd-GPR-English1KWW-3242008–4681.pdf

- 17.Villegas E, Eggum BO, Vasal SK, Kohli MM. Progress in nutritional improvement of maize and triticale. Food Nutr Bull. 1980;2:17–24 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertz ET, Bates LS, Nelson OE. Mutant gene that changes protein composition and increases lysine content of maize endosperm. Science. 1964;145:279–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bressani R. Protein quality of high-lysine maize for humans. Cereal Foods World. 1991;36:806–11 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bressani R. Nutritional value of high-lysine maize in humans. : Quality protein maize. St. Paul (MN): American Association of Cereal Chemists; 1992. p. 205–24 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knabe DA, Sullivan JS, Burgoon KG, Bockholt AJ. QPM as a swine feed. : Quality protein maize. St. Paul (MN): American Association of Cereal Chemists; 1992. p. 225–38 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivek BS, Krivanek AF, Palacios-Rojas N, Twumasi-Afriyie S, Diallo AO. Breeding quality protein maize (QPM): protocols for developing QPM cultivars. Mexico, DF (Mexico): CIMMYT; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjarnason M, Vasal SK. Breeding of quality protein maize (QPM). In: Janick J, editor. Plant breeding reviews. Vol. 9. Oxford (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 1992. p. 181–216 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbon BC, Larkins BA. Molecular genetic approaches to developing quality protein maize. Trends Genet. 2005;21:227–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geetha KB, Lending CR, Lopes MA, Wallace JC, Larkins BA. Opaque-2 modifiers increase gamma-zein synthesis and alter its spatial distribution in maize endosperm. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1207–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bressani R, Elias FL, Gomez-Brenes RA. Protein quality of opaque-2 corn evaluation in rats. J Nutr. 1969;97:173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai J, Messing J. Increasing maize seed methionine by mRNA stability. Plant J. 2002;30:395–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunaratna NS, De Groote H, Nestel P, Pixley KV, McCabe CP. A meta-analysis of community-based studies on quality protein maize. Food Policy. 2010;35:202–10 [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition: report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. WHO Technical Report Series no. 935; 2007 [cited August 2010]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_935_eng.pdf [PubMed]

- 30.Viteri FE, Martinez LC, Bressani R. Evaluation of protein quality maize, opaque-2 maize and common maize supplemented with amino acids and other sources of protein. Nutritional improvement of maize: proceedings of an international conference held at the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP); 1972 March 6–8; Guatemala City. Guatemala (C.A.): Talleres Graficos del INCAP; 1972. p. 191–204 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kies C, Fox HM. Protein nutritional value of opaque-2 corn grain for human adults. J Nutr. 1972;102:757–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine Protein and amino acids. Dietary Reference Intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. p. 145–55 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine Appendix E: DRI values for indispensable amino acids by life stage and gender group. Dietary Reference Intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. p. 459–65 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onofiok NO, Nnanyelugo DO. Weaning foods in West Africa: nutritional problems and possible solutions. Food Nutr Bull. 1998;19:27–33 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerrior S, Juan W, Basiotis P. An easy approach to calculating estimated energy requirements. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuss ET, Arscott SA, Bresnahan K, Pixley KV, Rocheford T, Hotz C, Siamusantu W, Chileshe J, Tanumihardjo SA. Adaptation to and intake patterns of traditional foods made from biofortified orange maize (Zea mays) in rural Zambia children. FASEB J. 2011; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark HE, Allen PE, Meyers SM, Tuckett SE, Yamamura Y. Nitrogen balances of adults consuming opaque-2 maize protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1967;20:825–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.FAO of the United States Comparison of nutritive value of common maize and quality protein maize. In: Maize in human nutrition; 1992 [cited August 2010]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/docrep/t0395e/T0395E00.htm#Contents

- 39.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 Suppl 1):S9–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Nations Children’s Fund, formerly UNICEF Overview of UNICEF-Assisted Nutrition Programme; 2009 [cited August 2010]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/supply/files/1._Overview_of_UNICEF_assisted_Nutrition_Programme.pdf

- 41.NRC Nutritionally improved maize. : Quality protein maize. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988. p. 21 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasal SK. High quality protein corn. Specialty corns. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press LLC; 2001. p. 85–129 [Google Scholar]

- 43.NRC Food and feed uses. : Quality protein maize. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. p. 46–56 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harvest Plus Biofortified maize crops for better nutrition; 2007 [cited September 2010]. Available from: http://crop.scijournals.org/cgi/reprint/47/Supplement_3/S-88

- 45.De Groote H, Chege Kimenju S. Comparing consumer preferences for color and nutritional quality in maize: Application of a semi-double-bound logistic model on urban consumers in Kenya. Food Policy. 2008;33:362–70 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muzhingi T, Langyintuo AS, Malaba LC, Banziger M. Consumer acceptability of yellow maize products in Zimbabwe. Food Policy. 2008;33:352–61 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stevens R, Winter-Nelson A. Consumer acceptance of provitamin A-biofortified maize in Maputo, Mozambique. Food Policy. 2008;33:341–51 [Google Scholar]

- 48.NRC The promise of QPM. : Quality protein maize. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. p. 35–40 [Google Scholar]