Abstract

Background

To alleviate the shortage of primary care physicians in rural communities, the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) introduced provisional licensure for international medical graduates (IMGs), allowing them to practise in under-served communities while completing licensing requirements. Although provisional licensing has been seen as a needed recruitment strategy, little is known about its impact on physician retention. To assess the relationship between provincial retention time and type of initial practice licence, we compared the retention of: (1) IMGs who began practice with a provisional licence; (2) fully licensed Memorial University medical graduates (MMGs); and (3) fully licensed medical graduates from other Canadian medical schools (CMGs).

Methods

Using administrative data from the NL College of Physicians and Surgeons, the 2004 Scott’s Medical Database, and the Memorial University postgraduate database, we identified family physicians/general practitioners (FPs/GPs) who began their practice in NL in the period 1997–2000 and determined where they were in 2004. We used Cox regression to examine differences in retention among these 3 groups of physicians.

Results

There were 42 MMGs, 38 CMGs and 77 IMGs in our sample. The median time for IMGs to qualify for full licensure was 15 months. Twenty-one physicians (13.4%) stayed in NL after beginning their practice (35.7% MMGs, 5.3% CMGs, 5.2% IMGs; p < 0.000). The median retention time was 25 months (MMGs, 39 months; CMGs, 22 months; IMGs, 22 months; p < 0.000). After controlling for Certificant of the College of Family Physicians status, CMGs (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.15; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29–3.60) and IMGs (HR = 2.03; 95% CI 1.26–3.27) were more likely to leave NL than MMGs.

Conclusions

Provisional licensing accounts for the largest proportion of new primary care physicians in NL but does not lead to long-term retention of IMGs. However, IMG retention is no worse than the retention of CMGs.

Many international medical graduates (IMGs) who respond to recruitment initiatives do not meet Canadian licensing requirements and require additional training and ongoing continuing medical education. To facilitate the entry of IMGs into practice in Canada, provinces haveintroduced programs such as provisional licences and pre-residency programs.1-4 To alleviate the shortage of primary care physicians in rural communities, Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) grants provisional licences for IMGs to provide primary care in under-served rural communities.4,5 Eligible candidates are graduates of accredited medical programs, have successfully completed the Medical Council of Canada evaluating examination (MCCEE) and part 1 of the qualifying exam (MCCQE part 1), have at least 1 year of postgraduate training, and have an employment offer from a sponsor approved by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Newfoundland and Labrador (formerly the Newfoundland Medical Board). IMGs must pass the second part of their Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Exam (MCCQE part 2) within 3 years of receiving a provisional licence, and obtain a full licence.5

Although a large number of studies have examined physician recruitment and retention, these studies focus largely on rural physicians and examine the practice locations of graduates of specific training programs, medical schools, or return-of-service programs. As a result, there has been comparatively little study of IMGs even though they form 23% of the physician workforce in Canada.6 The purpose of this article is to assess the relationship between provincial retention time and type of initial practice licence to determine whether IMGs with provisional licences remain in NL as long as medical graduates of the provincial medical school at Memorial University (MMGs) and graduates of other Canadian medical schools (CMGs).

Methods

We linked registration data for 8 years (1997–2004) from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Newfoundland and Labrador with the 2004 Scott’s Medical Database and the Memorial University postgraduate medical education database using the physician’s name, date of birth, and medical school, as these fields are common to all datasets. The Scott’s (formerly Southam) Medical Database was used to identify the work location of each physician in 2004. Scott’s Medical Database is an annually updated listing of 56 000 physicians in Canada who are members of the Canadian Medical Association and permit release of their information.7 This linkage allowed us to follow physicians in Canada once they left the province. The postgraduate medical education database identified which physicians had completed some or all of their residency training at Memorial University.

We included all general practitioners and family physicians who obtained their initial NL licence between 1997 and 2000. Because the medical licensing legislation was revised in 1996, this time frame included only those individuals who were licensed under the current policy. We excluded MMGs and CMGs who had a full licence before 1997, IMGs who held full or provisional licences before 1997 (older regulations), and physicians who received their licence after 2000 (insufficient follow-up time). In our primary analyses, we excluded physicians who practised in NL for 3 months or less, on the grounds that they were likely locum tenens. We repeated our analyses including these physicians.

We followed each physician until 31 July 2004 or until they terminated their initial licence (and presumably left the province). We compared: (1) MMGs with a full licence; (2) CMGs with a full licence; and (3) IMGs with a provisional licence.

Statistical analyses

We used frequencies, means and standard deviations to describe the sample characteristics. Chi-square tests, ANOVA, and the Mantel–Cox test were used to identify differences among the 3 physician groups with respect to sex, year of graduation, whether some or all of their postgraduate residency training had been done at Memorial University, age at licensing, Certificant of the College of Family Physicians (CCFP) designation, and total time in NL. Cox regression analysis was used to identify differences in the retention of the physician groups. Potential predictors for each regression model were selected on the basis of the bivariate analyses (i.e., chi-square and ANOVA). Assumptions for the regression model, including proportionality of hazards, were met. Our final regression models include only significant covariates.

We grouped year of graduation into 4 categories: before 1973, 1973–1979, 1980–1989, and 1990–1998. We selected 1973 as a cut-off, as this was the graduation year of the first Memorial University medical class. Both the licensing data and the Scott’s Medical Database were consulted so that physicians who held a NL licence but did not work in the province were identified as working outside NL. The time in practice in NL was calculated by subtracting the date when the initial licence was awarded from the date that it ended. Total time in NL does not include practice time from subsequent licences.

Results

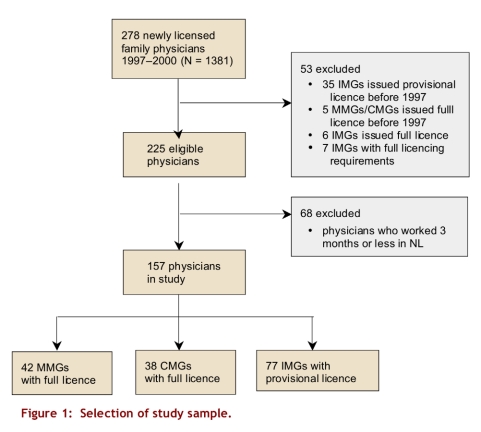

Of the 278 FPs/GPs who received a new licence between 1997 and 2000, we excluded 35 IMGs who were provisionally licensed before 1997 and 5 CMGs/MMGs who worked in the province with a full licence before 1997 (Figure 1). In addition, we excluded 6 IMGs who held a full licence and another 7 IMGs who had met the requirement for full licensure but were recorded in the registration database as having a provisional licence. These 13 IMG physicians were excluded because their numbers were too small to allow for meaningful analyses. From the remaining 225 physicians, for our primary analyses, we excluded 68 physicians who practised in the province for 3 months or less, leaving a study sample of 157 physicians: 48 MMGs with full licences, 32 CMGs with full licences, and 77 IMGs with provisional licences.

Figure 1.

Selection of study sample

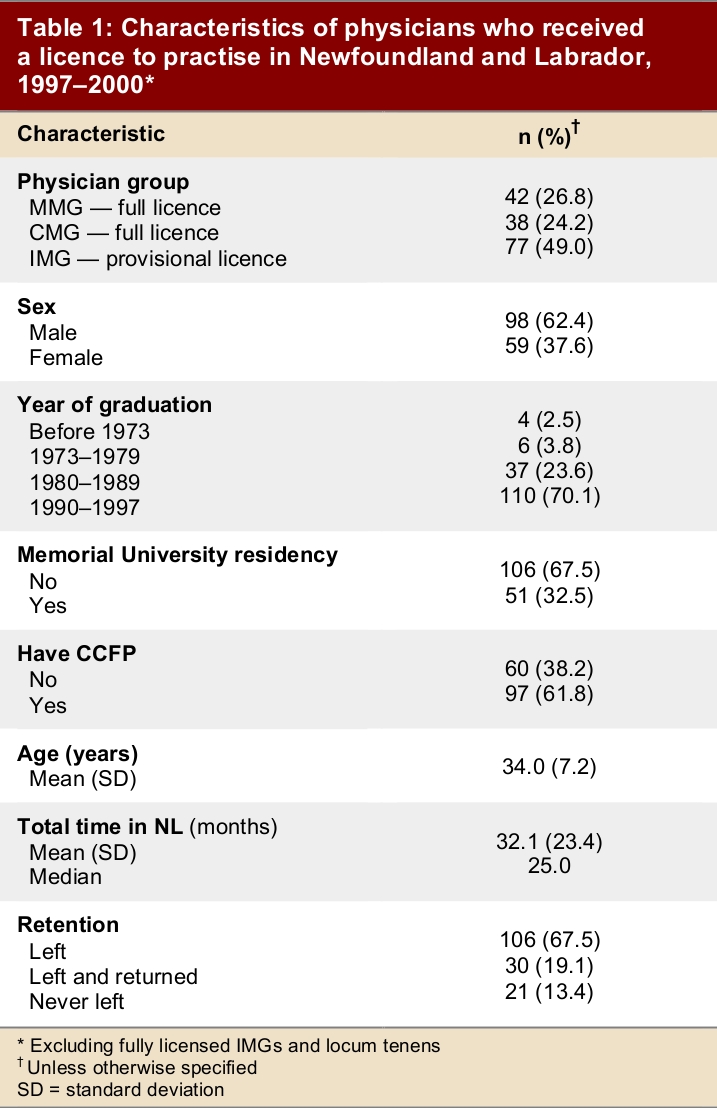

The characteristics of the physicians in the primary analysis are presented in Table 1. IMGs with provisional licences formed the largest proportion (49.0%) of physicians in the cohort, followed by MMGs (26.8%) and CMGs (24.2%). The largest proportion (46.8%) of IMGs had graduated from medical schools in Africa. IMG physicians took a median of 15 months to qualify for full licensure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physicians who received a licence to practise in Newfoundland and Labrador, 1997–2000

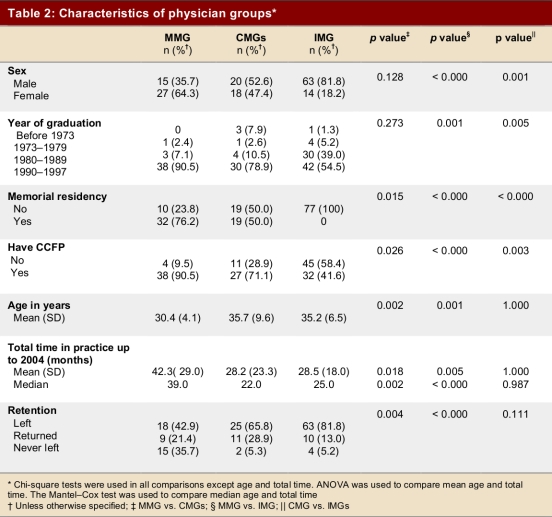

Compared with MMGs, a larger proportion of IMGs were male, graduated before 1990, had not done any of their postgraduate residency training at Memorial University, did not have a CCFP designation, were older, worked for less time in NL, and never left the province after starting practice (Table 2). Compared with CMGs, a larger proportion of IMGs physicians were male, had graduated before 1990, had not done any of their residency at Memorial University and did not have a CCFP designation, but there were no statistically significant differences with respect to age, the amount of time they worked in NL before leaving, the proportion who were in NL in 2004 or whether they left and/or returned to the province.

Table 2.

Characteristics of each physician group

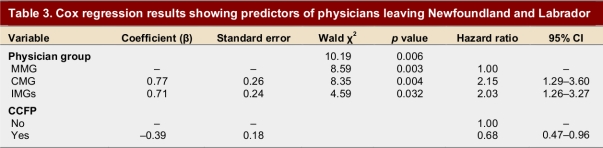

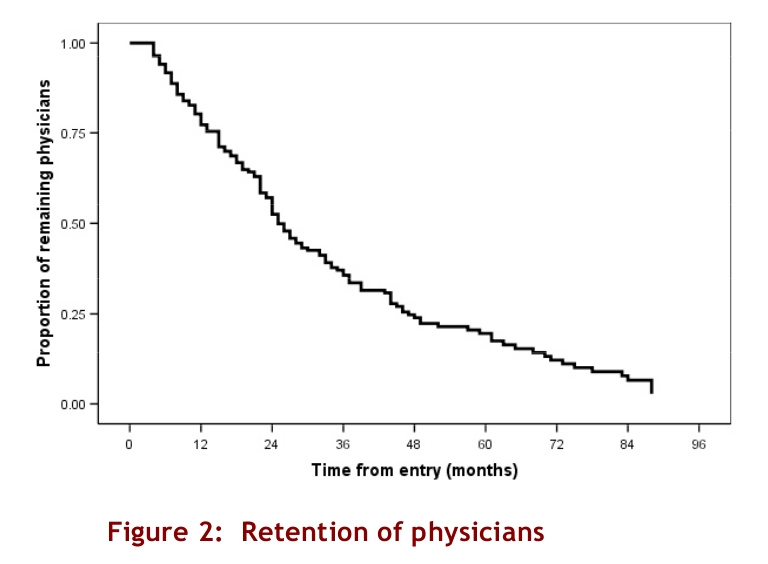

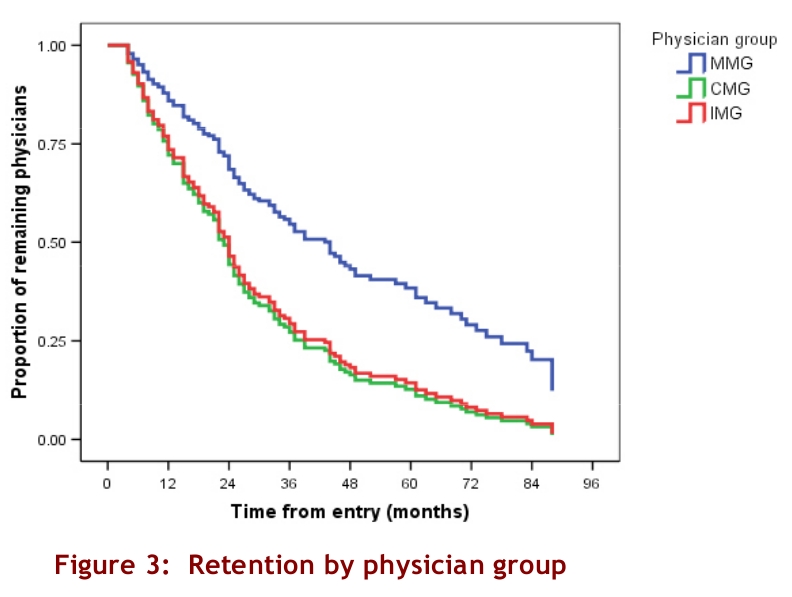

Cox regression analysis allowed us to compare how long MMGs, CMGs and IMGs worked in NL before leaving, taking into account any other differences between these groups. The survival curve shows the proportion of each group that remains at any given time. The median practice time for all physicians was just under 2 years (Figure 2). After controlling for CCFP status, CMGs and IMGs were found to be more likely to leave NL than MMGs (Table 3). Physicians with the CCFP designation were less likely to leave NL than those without the CCFP designation (or 1.47 [CI 1.04–2.13] times more likely to stay, based on the inverse of the hazard ratio). As shown in Figure 3, the median practice time for MMGs was greater (roughly 40 months) than for IMGs or CMGs (24 months). There was no difference between IMGs and CMGs with respect to practice times.

Figure 2.

Retention of physicians

Table 3.

Cox regression results showing predictors of physicians leaving Newfoundland and Labrador

Figure 3.

Retention by physician group

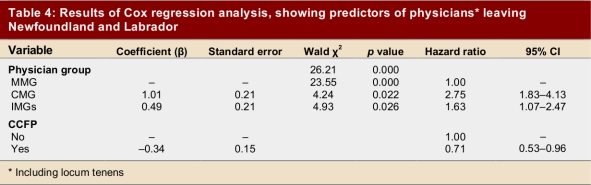

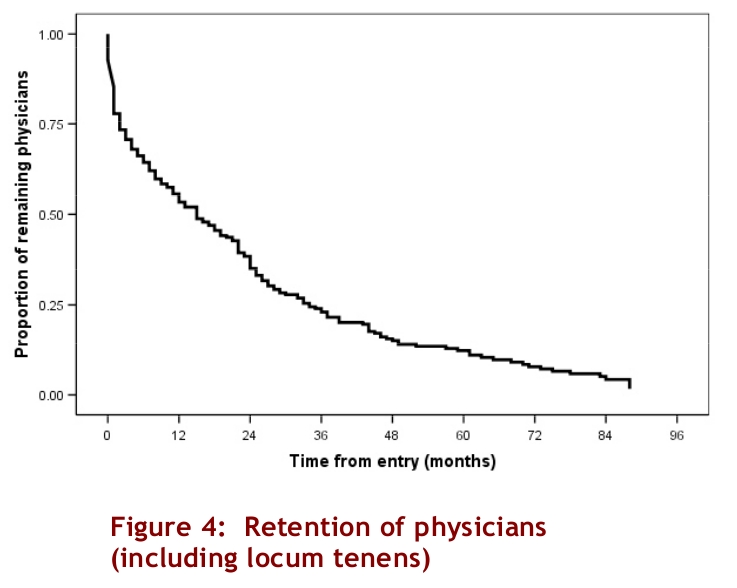

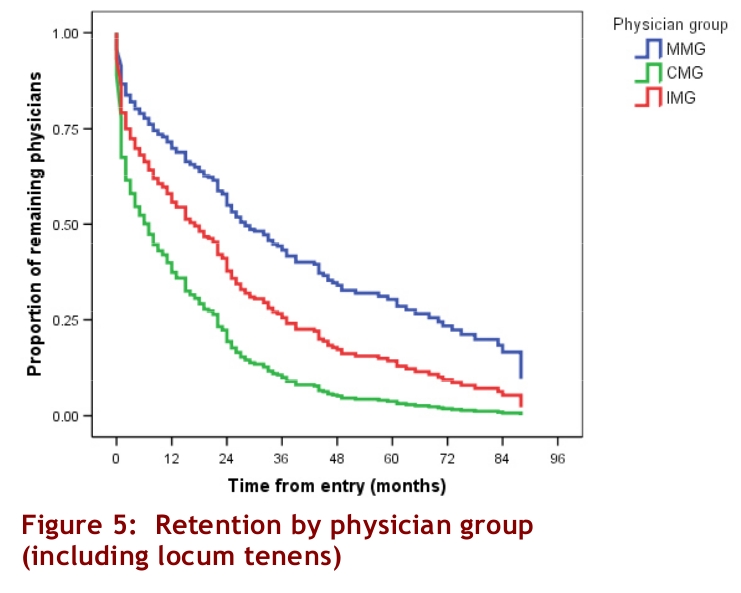

We repeated our analysis including the 68 physicians who stayed 3 months or less. After controlling for CCFP status and physician groups using Cox regression, the median practice time for all physicians was found to be just over 18 months (Figure 4). When CCFP status was controlled for, CMGs and IMGs were found to be more likely to leave NL than MMGs (Table 4). Physicians with the CCFP designation were less likely to leave NL than those without the CCFP designation. As shown in Figure 5, the median practice time for MMGs was greater (roughly 36 months) than for IMGs (22 months) or CMGs (12 months).

Figure 4.

Retention of physicians (including locum tenens)

Table 4.

Results of Cox regression analysis, showing predictors of physicians* leaving Newfoundland and Labrador

Figure 5.

Retention by physician group (including locum tenens)

Discussion

The overall retention of newly licensed family physicians in NL is low (13.4%), but is higher among graduates of the provincial medical school than among graduates of other Canadian or international medical schools. This supports the suggestion arising from earlier studies that medical schools contribute substantially to local physician supply.8 Although our study confirms that turnover is high among IMGs, it also highlights that turnover is equally high among CMGs. Previous studies have suggested that poor IMG retention, particularly in rural NL,may stem from a lack of cultural or religious venues for IMGs.9 These findings suggest that other factors may also play an important role in physician retention in the province. Future studies should examine the factors that contribute to the poor retention of both IMGs and CMGs in the province.

Newfoundland and Labrador, like the rest of Canada and other Western countries, has traditionally relied on IMGs to address shortages in physician supply, particularly in rural and remote communities.[1–3,10] In 2004, IMGs constituted 23.0% of the family physician workforce in Canada; the lowest proportion of IMGs were in Quebec (11.1%) and Prince Edward Island (16.0%), while the highest were in Saskatchewan (61.7%) and NL (44.5%).6 Likewise, IMGs physicians make up over one quarter of the physician workforce in other countries, including the United States (25.5%), Australia (26.5%), New Zealand (34.5%) and the United Kingdom (28.3%).11

Almost half of the physicians in our study sample were provisionally licensed IMGs. Provisionally licensed IMGs make up roughly 30% of the physician workforce in NL, as compared with roughly 5% in Canada.12 Although IMGs make up a large proportion of newly licensed physicians in the province, relatively few remain in the province 1 year after earning full licensure. By 2004, 70.1% of IMGs remained in Canada (according to the Scott’s Medical Database), a rate similar to that for MMGs (81.0%) and CMGs (73.7%). Of the IMGs who moved elsewhere in Canada, 25.6% were working in Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta or Saskatchewan), 62.7% in Ontario, and 11.6% in the Maritimes (Prince Edward Island or Nova Scotia). The majority of these IMG physicians (76.7%) were working in urban communities (10 000 or more population). These findings confirm the widely held belief that NL provides an entry point to practice elsewhere in Canada.12 They also suggest that most IMG physicians move to urban centres where a larger number of people who share their ethnic background live.

Physicians who held a CCFP designation were less likely to leave NL than those who did not. We used registration data from the provincial College of Physicians and Surgeons because it is the only province-wide data set that includes licensing data. Although licences must be renewed annually, the fee to change or update registration information (currently $275) may discourage physicians from changing provisional to full licences and updating recently acquired credentials (such as CCFP or LMCC [Licentiate of the Medical College of Canada] designations). For example, although 47 IMGs had qualified for a full licence, only 31 had held a full licence in NL (i.e., had applied for and were granted a full licence). Physicians who intend to continue to practise in NL may be more likely to update their registration information than those who do not.

Roughly 30% (68 of 225) of the eligible sample of newly licensed physicians practised in NL for a short period of time and were likely locum tenens. CMGs (60.3%) and graduates from the 1990s (64.7%) made up the largest proportion of these physicians. When these physicians are included in the sample, CMGs have significantly lower retention and practice times than both MMGs and IMGs. We used 3 months as the cut-off for locums based on consultation with recruiters and other physicians. Using higher cut-offs (up to 6 months) excluded an additional 14 physicians but did not change the overall findings.

Almost one quarter (22.1%) of physicians who left NL returned to the province. The proportion of returning physicians was almost equally split between MMGs, CMGs and IMGs, although a larger proportion (80%) of returning physicians were more recent graduates. These findings suggest that new physicians are highly mobile, possibly more so than previous generations. New physicians may prefer to try out different practice locations before establishing a more permanent practice. It is unlikely that MMG and CMG physicians were leaving practice for specialist training, as was commonplace before the 1990s, when there was greater flexibility in postgraduate training and physicians were able to practise after the 1-year rotating internship. Among IMGs, only 1 physician entered the Memorial University residency program, although others may have entered residency programs elsewhere.

Study limitations

We examined data for FPs/GPs who received their first licence in NL between 1997 and 2000; factors related to provisional licensing and retention of specialists may differ. Moreover, because registration data did not reliably capture practice addresses, we could not include rural practice as a covariate. We were also unable to determine whether physicians who remained in NL moved within the province. Given that the provisional licensing policy allows IMGs to work in rural communities, we were not able to determine whether IMGs moved to urban practices once they were fully qualified. Between 1997 and 2000, licensing policies restricted new physicians from practising in St. John’s, the province’s largest urban centre. We are therefore confident that most physicians in the study began practice in smaller communities (the largest, Corner Brook, with a population of 30 000).

Conclusions

Using licensing data from the provincial medical registrar, we found that retention in a cohort of newly licensed FPs/GPs was low; fewer than 1 in 7 physicians remained in the province up to 7 years later. Half had left after roughly 2 years, although locally trained physicians remained in the province twice as long as IMGs and CMGs. There was no difference between the retention of IMGs and that of CMGs. IMG remained in the province for roughly 1 year after earning a full licence. Although provisional licences and training programs facilitate the entry of IMGs into medical practice in Canada, they do not lead to long-term provincial retention, but provide a short-term solution to ongoing physician shortages in NL. Given that IMGs form a substantial proportion of practising physicians in the province, eliminating provisional licensing would have a detrimental impact on physician supply in the province.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research. Maria Mathews holds a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Regional Partnership Program (#136562).

Biographies

Maria Mathews, PhD, is an associate professor of Health Policy/Health Care Delivery in the Division of Community Health & Humanities, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

Alison C. Edwards, MSc, was a medical researcher in the Division of Community Health & Humanities, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. She is currently enjoying her retirement.

James T. B. Rourke, MD, FCFP (EM), MClSc, is the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: This study was funded by the Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research. The Centre had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, report writing, or the decision to submit for publication.

Contributors: All authors read and approved the manuscript and met the requirements for authorship. Dr. Mathews conceived and designed the study, conducted the analysis and prepared the draft of the manuscript. Ms. Edwards linked and cleaned the data, and provided feedback on the draft. Dr. Rourke reviewed the study design and provided feedback on the draft of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Andrew R, Bates J. Program for licensure for international medical graduates in British Columbia: 7 years' experience. CMAJ. 2000;162(6):801–3. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10750470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasmith L. Licence requirements for international medical graduates: should national standards be adopted? CMAJ. 2000;162(6):795–6. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10750469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barer M L, Stoddart G L. Toward integrated medical resource policies for Canada: 4. Graduates of foreign medical schools. CMAJ. 1992;146(9):1549–54. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=1571866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barer ML, Wood L, Schneider DG. Toward improved access to medical services for relatively underserved populations: Canadian approaches, foreign lessons. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Medical Board Regulations under the Medical Act (O.C. 90-941) 2005. [accessed 2005 Jan 10]. http://www.gov.nf.ca/hoa/regulations/rc961113.htm.

- 6.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, Distribution and Migration of Canadian Physicians 2004. 2005. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=PG_385_E&cw_topic=385&cw_rel=AR_14_E.

- 7.MD Select. MD Select User’s Manual. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathews Maria, Rourke James T B, Park Amanda. National and provincial retention of medical graduates of Memorial University of Newfoundland. CMAJ. 2006;175(4):357–60. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060329. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16908895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayo Erin, Mathews Maria. Spousal perspectives on factors influencing recruitment and retention of rural family physicians. Can J Rural Med. 2006;11(4):271–6. http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/staticContent/HTML/N0/l2/cjrm/vol-11/issue-4/pdf/pg271.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregory Ann T, Armstrong Ruth M, Van Der Weyden Martin B. Rural and remote health in Australia: How to avert the deepening health care drought. Med J Aust. 2006;185(11-12):654–60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00744.x. http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/185_11_041206/gre11187_fm.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullan Fitzhugh. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1810–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050004. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=16251537&promo=ONFLNS19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Audas Rick, Ross Amanda, Vardy David. The use of provisionally licensed international medical graduates in Canada. CMAJ. 2005;173(11):1315–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050675. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16301695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]