Abstract

Purpose:

To examine the effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® on neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia.

Patients and methods:

Randomized, controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial involving 410 outpatients with mild to moderate dementia (Alzheimer’s disease with or without cerebrovascular disease, vascular dementia), scoring at least 5 on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), with at least one item score of 3 or more. Total scores on the SKT cognitive test battery (Erzigkeit’s short syndrome test) were between 9 and 23. After random allocation, the patients took 240 mg of EGb 761® or placebo once daily for a period of 24 weeks. Changes from baseline to week 24 in the NPI composite and in the SKT total score were the primary outcomes. The NPI distress score was chosen as a secondary outcome measure to evaluate caregivers’ distress.

Results:

The NPI composite score improved by −3.2 (95% confidence interval −4.0 to −2.3) in patients taking EGb 761® (n = 202), but did not change (−0.9; 0.9) in those receiving placebo (n = 202), which resulted in a statistically significant difference in favor of EGb 761® (P < 0.001). Treatment with EGb 761® was significantly superior to placebo for the symptoms apathy/indifference, sleep/night-time behavior, irritability/lability, depression/dysphoria, and aberrant motor behavior. Caregivers’ distress evaluation revealed similar baseline pattern and improvements.

Conclusion:

Treatment with EGb 761®, at a once-daily dose of 240 mg, was safe, effectively alleviated behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with mild to moderate dementia, and improved the wellbeing of their caregivers.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, patients, caregivers, Ginkgo biloba, EGb 761®

Introduction

The primary risk factor for both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VaD) is age. The extension of life expectancy results in a rising number of patients with dementia and associated symptoms. The core syndrome of dementia, which serves as a key diagnostic feature, is cognitive impairment, but neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPSs) are common as well. Almost all people with dementia are affected by these symptoms at some point during the progression of the disorder.1 This may result in long-term hospitalization, increased use of medication, and a decrease in quality of life for patients and caregivers.2

Prevalence of any one NPS was 61% in a cross-sectional study, and 69%, who were symptom-free at baseline, had at least one symptom when followed up 18 months later.3,4 In another study, 75% of dementia patients exhibited at least one such symptom in the previous month; two or more symptoms were observed in 55% of cases.5 Between 43% and 47% of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) exhibited at least one neuropsychiatric symptom, and up to 80% of the demented patients had presented at least one neuropsychiatric symptom since the beginning of their cognitive impairment.5,6 Neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with dementia from its early beginning and cannot be described as concomitant features of advanced disease states.5 Like cognitive disturbances, they should be considered as an integral part of the core psychopathology.5,7

There were no differences in the prevalence of NPSs in patients with AD type or other forms of dementia, including VaD, apart from the item aberrant motor behavior, which was more frequent in AD. The most frequent symptoms in dementia patients were apathy, depression, and agitation/aggression.5 NPS severity was no different between AD and VaD patients on initial assessment of a memory disorders clinic population with mild to moderate dementia. However, NPSs increased with severity of dementia in this group.8

Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® has been reported to be effective in the symptomatic treatment of dementia, in particular when NPSs are present.9–12 Clinically significant effects of EGb 761® on NPSs have been described for patients suffering from age-associated cognitive decline as well as for patients with dementia.13–15 The molecular basis of such effects is not yet fully understood, but there is evidence of neuroprotective properties, including inhibition of synaptotoxic Aβ oligomer formation as well as antagonism of β-amyloid toxicity.16–19 EGb 761® is a polyvalent radical scavenger that improves mitochondrial function,20–22 decreases blood viscosity, and enhances microperfusion.23 Modulation of the serotonin system,24 increasing dopamine levels in prefrontal cortical areas,25 perhaps by inhibition of the norepinephrine transporter,26 attenuation of a hyperactivated hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis,27–29 and improvement of neuronal insulin sensitivity may play a role, since these pharmacodynamic actions of EGb 761® target pathomechanisms that are common to dementia and behavioral disorders.

Here we report on secondary analyses of data from a recently published clinical trial of a once-daily formulation containing 240 mg of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761®.12 The goal of these secondary analyses was the assessment of treatment effects of EGb 761® on single NPSs in patients with dementia as well as on relieving the related caregiver distress.

Material and methods

The clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) guideline for good clinical practice (GCP), and the provisions of local laws.30 The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Pharmacology Center at the Ukraine Ministry of Health. Before enrolment, oral and written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their caregivers. At a start-up meeting, investigators and clinical staff involved in the trial were trained in GCP standards and legal requirements. Moreover, they were trained by experienced psychiatrists and neuropsychologists in the administration of tests and rating scales used for diagnosis and efficacy assessment.

Study population

Patient selection, patient disposition, trial design, and methods are described in detail elsewhere.12 Briefly, outpatients (≥50 years of age, 20 centers) with mild to moderate dementia due to probable AD (according to NINCDS/ADRDA research diagnostic criteria),31 possible AD (NINCDS/ADRDA) with cerebrovascular disease (CVD) (as specified by NINDS/AIREN criteria) or probable VaD (NINDS/AIREN) were admitted32 if they scored 35 or worse in the cognitive part of the Test for Early Detection of Dementia with Discrimination from Depression (TE4D-cog),33 between 9 and 23 in the SKT cognitive test battery total score,34,35 below 6 in the clock-drawing test (CDT),36 and at least 5 on the 12-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).7 In at least one item of the NPI (except delusions or hallucinations), patients had to score at least 3, and their total score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) had to be less than 20.37 A caregiver had to be available to provide information on the patient’s behavior and ability to perform activities of daily living.

Patients suffering from other psychiatric or neurological disorders or having severe somatic illnesses were excluded. Treatment with other antidementia drugs, Ginkgo supplements, cholinergic, anti-cholinergic or hemorheologically active drugs was prohibited throughout the trial.

Study design and intervention

After a medication-free screening period of up to 4 weeks, patients were randomly assigned to receive either Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® at a dose of 240 mg once a day or placebo in a double-blind fashion during the subsequent 24-week treatment period. EGb 761® is a dry extract from Ginkgo biloba leaves (35–67:1), extraction solvent: acetone 60% (w/w). The extract is adjusted to 22.0%–27.0% Ginkgo flavonoids, calculated as Ginkgo flavone glycosides, and 5.0%–7.0% terpene lactones, consisting of 2.8%–3.4% ginkgolides A, B, C, and 2.6%–3.2% bilobalide, and contains less than 5 ppm ginkgolic acids. Drug and placebo were manufactured and provided by Dr Willmar Schwabe GmbH and Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Outcome measures

Considering the emphasis on neuropsychiatric features at inclusion, the 12-item NPI was chosen to be a primary efficacy measure in addition to the SKT (a cross-culturally validated 9-item cognitive test battery). Each of the 12 types of abnormal behavior is explored by a number of pertinent screening questions and, if present, scored by its frequency of occurrence and its severity. The total composite score obtained by summing up the single item scores may range from 0 to 144, with higher scores indicating more behavioral problems.

In addition, a score for caregivers’ distress is assigned for each type of abnormal behavior present. The total distress score may range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe distress suffered by the caregiver. An improvement in the total composite score by four points or more in an individual patient is judged by experts to be clinically significant.38

The NPI caregivers’ distress score and the rate of clinically meaningful response (improvement by at least 4 points on the NPI composite score) were therefore also included as secondary outcome measures.

Efficacy assessments were performed at baseline, week 12, and week 24. Safety was assessed by physical examination, electrocardiography, and laboratory tests at screening and week 24. Adverse events were recorded at all regular visits, at week 6, and week 18 by phone calls and at the study termination visit (week 24 or early termination).

Statistical analysis

The methods for the statistical analysis are described in detail elsewhere.12 In short, two primary endpoints, the change in the SKT total score and the NPI total score, were defined to assess efficacy in the cognitive and neuropsychiatric domain, respectively. These endpoints were analyzed using an overall type-I error rate of α = 0.05 by applying an analysis of covariance procedure with the factors treatment and center and the baseline value of the respective variable as a covariate. The analysis was based on the full analysis dataset according to the intention-to-treat principle and included all patients who received randomized study treatment at least once and had at least one measurement of the primary efficacy parameters during the randomized treatment period. Secondary efficacy variables as presented in this paper were evaluated descriptively without control of the type-I error rate, and the P-values should be considered accordingly.

Results

The main results for the primary and secondary outcome parameters of this randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial have been reported elsewhere.12 Here we describe the treatment effects of EGb 761® and placebo on neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia derived from single NPI items, total composite scores, and caregiver distress scores.

Baseline characteristics of patients, broken down by treatment group, are presented in Table 1. The mean NPI total score dropped by −3.2 ± 6.1 (mean ± standard deviation) points in the EGb 761®-treated patients between baseline and week 24. The mean caregiver distress score decreased in parallel by −1.2 ± 3.4 points. In patients receiving placebo, the NPI total score remained unchanged (0.0 ± 6.1), and the corresponding caregiver distress score increased slightly by 0.3 ± 3.4. Drug–placebo differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001, two-sided t-test) in both between-group comparisons. A clinically meaningful response, defined as an improvement by at least 4 points on the NPI total score,38 was achieved in 45.0% of patients treated with EGb 761® and in 23.8% of patients receiving placebo (P < 0.001, two-sided χ2-test, for between-group comparison).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (full analysis set), means ± standard deviations and two-sided P-values of the t-test or numbers (percentage) and two-sided P-values of the χ2-test, as appropriate

| Characteristic | EGb 761®(n = 202) | Placebo (n = 202) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 139 (69%) | 133 (66%) | 0.524 |

| Male | 63 (31%) | 69 (34%) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| probable AD | 64 (32%) | 57 (28%) | 0.364 |

| possible AD with CVD | 99 (49%) | 113 (56%) | |

| probable VaD | 39 (19%) | 32 (16%) | |

| Age (years) | 65 ± 10 | 65 ± 9 | 0.550 |

| Height (cm) | 166 ± 8 | 167 ± 8 | 0.298 |

| Weight (kg) | 74 ± 14 | 74 ± 14 | 0.666 |

| SKT total score | 16.7 ± 3.9 | 17.2 ± 3.7 | 0.163 |

| NPI total score | 16.4 ± 8.1 | 17.0 ± 8.2 | 0.393 |

| NPI distress score | 9.6 ± 5.6 | 10.0 ± 5.4 | 0.477 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; SKT, Erzigkeit’s short syndrome test; VaD, vascular dementia.

The mean composite and distress scores at baseline for all 12 NPI items are shown in Table 2. The highest baseline composite scores were found for apathy/indifference, sleep/night-time behavior, irritability/lability, and anxiety. Caregivers reported that irritability/lability, sleep/night-time behavior, and apathy/indifference were the most distressing symptoms.

Table 2.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory item scores at baseline (full analysis set), means ± standard deviations and two-sided P-values of the t-test

| Item |

Composite scorea |

Caregiver distress score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGb 761® | Placebo | P-value | EGb 761® | Placebo | P-value | |

| Delusions | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.990 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.228 |

| Hallucinations | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.771 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.694 |

| Agitation/aggression | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | 0.856 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.922 |

| Depression/dysphoria | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 2.5 ± 2.4 | 0.998 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.817 |

| Anxiety | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 3.2 ± 2.4 | 0.422 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 0.322 |

| Elation/euphoria | 0.3 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | 0.443 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.490 |

| Apathy/indifference | 3.0 ± 2.4 | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 0.695 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 0.482 |

| Disinhibition | 0.3 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 1.2 | 0.370 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.329 |

| Irritability/lability | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 0.235 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 0.445 |

| Aberrant motor behavior | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 0.5 ± 1.4 | 0.805 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.506 |

| Sleep and night-time behavior | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 0.250 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 0.393 |

| Appetite and eating disorders | 0.5 ± 1.5 | 0.6 ± 1.6 | 0.385 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.759 |

Note:

frequency × severity.

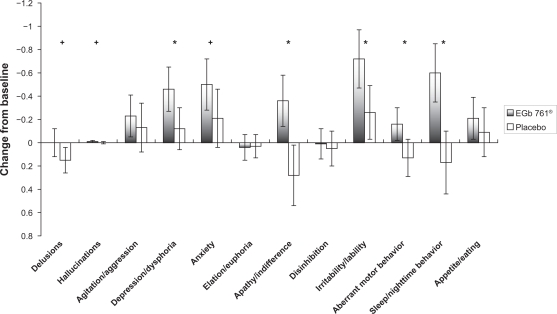

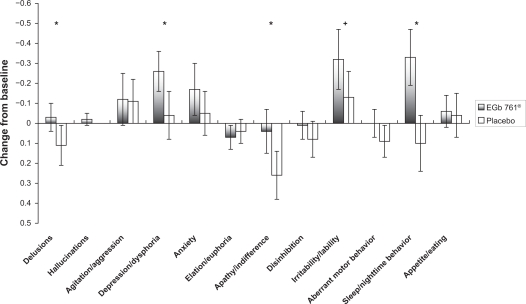

As shown in Figure 1, the average improvements in NPI composite scores after the 24-week EGb 761® treatment period were most pronounced for sleep/night-time behavior, apathy/indifference, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behavior, and depression/dysphoria (all statistically significantly different from placebo as indicated in Figure 1). A similar effect profile is observed for changes in caregiver distress scores, with marked effects also observed in sleep/night-time behavior and depression/dysphoria (statistically significantly different from placebo as indicated in Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Changes from baseline to week 24 in composite scores of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory by item (means, 95% confidence intervals).

Notes: +P < 0.1; *P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Changes from baseline to week 24 in caregiver distress scores of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory by item (means, 95% confidence intervals).

Notes: +P < 0.1; *P < 0.05.

EGb 761® was safe and well tolerated, with a lower number of adverse events reported in the active treatment group than in the placebo group. Specifically, dizziness and tinnitus occurred more frequently under placebo treatment. Details have been reported and discussed elsewhere.12

Discussion

Significant treatment effects of a once-daily application of 240 mg EGb 761® on many of the neuropsychiatric symptoms evaluated by the 12-item NPI were found in prospective secondary analyses of this clinical trial. These results further support the efficacy of the once-daily application of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® in the treatment of patients with AD, VaD, or dementia with mixed pathology associated with NPSs, as demonstrated by confirmatory primary analysis based on the NPI total score.

Clinical efficacy of EGb 761® in the treatment of NPSs has already been postulated by Hoerr, who reviewed former studies in patients with age-associated cognitive decline, and it was confirmed recently by Scripnikov for patients with dementia.13,15 Our clinical trial focused on patients with dementia – AD, VaD, or mixed type – who were selected specifically as suffering from NPSs. This was achieved by stipulating a baseline composite score of at least 5 points on the 12-item NPI, with at least one item score not lower than 3. The NPI total composite score also served as a co-primary outcome criterion for the efficacy assessment.

The profile of NPSs in our population is slightly different from those reported in a previous 22-week trial of EGb 761®, and the baseline severity of symptoms is lower.15,39 Disease severity and stage-specific differences in behavioral symptom manifestations might influence overall treatment response as measured by an aggregate assessment tool such as NPI.40 As a consequence, the reported response rate (improvement by at least 4 points) might be lower in our clinical trial, in which the deterioration of symptoms in the placebo group was less pronounced, and even some slight improvement was observed in some symptoms with placebo treatment.

The pattern of neuropsychiatric symptoms found in our patients was consistent with that reported from a population-based study in which patients with dementia also scored highest for the symptoms apathy/indifference, anxiety, depression/dysphoria, agitation/aggression, aberrant motor behavior, and irritability/lability.3 It therefore appears that our sample was quite representative of dementia patients encountered in everyday practice.

The caregiver distress scores at baseline closely match those of the NPI composite scores, with slight differences in ranking of severity of apathy/indifference, sleep/night-time behavior, and irritability/lability. Overall, the symptoms rated as most prominent in the patients were also perceived as most disturbing by the caregivers. Similarly, the relief from distress, which was experienced by caregivers during the treatment period, seems to be driven by the symptoms that improved most in the patients.

The elevation and stabilization of mood and the observed decrease in anxiety levels seem to be in line with the effects of EGb 761® on the dopamine and serotonin systems as well as on the HPA axis.24–29

Recently, a pooled data analysis of the moderate-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine, a descriptive review of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, and a review of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine summarized the evidence for the efficacy of these substances in the treatment of NPSs.40–42 Beneficial effects of memantine were reported for delusions and agitation/aggression in patients with moderate to severe AD.41 Cummings concluded that most double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and open-label assessments suggest some treatment benefit of antidementia agents, though not all demonstrated drug–placebo differences.40 This is consistent with the summary conclusion that, at best, cholinesterase inhibitors appear to have a modest impact on the broad spectrum of NPSs in AD. In contrast, EGb 761® showed a significant effect on a broad range of symptoms. However, caution is warranted when trying to compare treatment effects observed in different studies, because they may depend on the characteristics of the particular patient population, such as profile and severity of behavioral symptoms at baseline, severity or stage of dementia, residential status, linguistic and cultural diversities of study sites, and use of psychotropic drugs. Moreover, the 10-item version of the NPI was used in some of the earlier trials.

In summary, the present, and a previous independent trial in patients selected using the same criteria for dementia and NPSs,15 consistently demonstrated statistically significant and clinically relevant drug–placebo differences in favor of EGb 761® for the composite score, the caregiver distress score, and several NPI item scores (eg, apathy/indifference, sleep/night-time behavior, irritability/lability, depression/dysphoria). The importance of alleviating NPSs is underlined by the negative impact such symptoms have on the quality of life of patients with dementia,43–45 the burden experienced by caregivers, and the roles that NPSs and NPS-related caregiver distress play in decisions about nursing home placement.46–48

Conclusion

It can be concluded that Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® at a once-daily dose of 240 mg is safe and effectively alleviates NPSs in patients with AD, VaD, and dementia with mixed pathology, benefitting both patients and their caregivers.

Acknowledgments/disclosures

The authors wish to thank Dr Gerhard Lorkowski, Gauting, for assistance with the first draft of the manuscript. RI and NB are scientific advisors to Schwabe; NB participated in the trial as investigator; RH is an employee of Schwabe.

References

- 1.Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, et al. The behavior rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’ disease. The Behavioral Pathology Committee of the Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(9):1349–1357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin IS, Carter M, Mastermann D, Fairbanks L, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):469–474. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JCS. Mental and behavioural disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache Country Study on the Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):707–714. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinberg M, Sheppard JM, Tschanz JT, et al. The incidence of mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: the Cache County Study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(3):340–345. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky ST. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan DC, Kasper JD, Black BS, Rabins PV. Prevalence and correlates of behavioural and psychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling elders with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: the Memory and Medical Care Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(2):174–182. doi: 10.1002/gps.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings JL. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. 1997;48(Suppl 6):S10–S16. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_6.10s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson C, Brodaty H, Trollor J, Sachdev P. Behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia subtype and severity. Int Psychogeriat. 2010;22(2):300–305. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IQWiG Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen . Cologne: IQWiG; 2008. Ginkgohaltige Präparate bei Alzheimer Demenz. Abschlussbericht. Auftrag A05-19B Version 10 [Ginkgo in Alzheimer‘s disease IQWiG Reports Commission No A05-19B Version 10]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasper S, Schubert H. Ginkgo-Spezialextrakt EGb 761® in der Behandlung der Demenz: Evidenz für Wirksamkeit und Verträglichkeit [Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® in the treatment of dementia: evidence of efficacy and tolerability] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2009;77(9):494–506. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinmann S, Roll S, Schwarzbach C, Vauth C, Willich SN. Effects of Ginkgo biloba in dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2010. Mar, [serial on the internet]. [cited 2010 Nov 15];14:[12 p.]. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2318-10-14.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ihl R, Bachinskaya N, Korczyn AD, et al. Efficacy and safety of a once-daily formulation of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® in dementia with neuropsychiatric features. A randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi: 10.1002/gps.2662. Epub 2010 Dec 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoerr R. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): effects of EGb 761®. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl 1):S56–S61. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider LS, DeKosky ST, Farlow MR, Tariot PN, Hoerr R, Kieser M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of two doses of Ginkgo biloba extract in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2(5):541–551. doi: 10.2174/156720505774932287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scripnikov A, Khomenko A, Napryeyenko O, for the GINDEM-NP Study Group Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® on neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: findings from a randomised controlled trial. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2007;157(13–14):295–300. doi: 10.1007/s10354-007-0427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramassamy C, Longpré F, Christen Y. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) in Alzheimer’s disease: is there any evidence? Current Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(3):253–262. doi: 10.2174/156720507781077304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyer S, Lannert H, Nöldner M, Chatterjee SS. Damaged neuronal energy metabolism and behavior are improved by Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) J Neural Transm. 1999;106(11–12):1171–1188. doi: 10.1007/s007020050232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Wu Z, Butko P, et al. Amyloid-β-induced pathological behaviors are suppressed by Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® and ginkgolides in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2006;26(50):13102–13113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3448-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastianetto S, Ramassamy C, Doré S, Christen Y, Poirier J, Quirion R. The Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) protects hippocampal neurons against cell death induced by beta-amyloid. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(6):1882–1891. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kampkötter A, Pielarski T, Rohrig R, et al. The Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® reduces stress sensitivity, ROS accumulation and expression of catalase and glutathione S-transferase 4 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckert A, Keil U, Kressmann S, et al. Effects of EGb 761® Ginkgo biloba extract on mitochondrial function and oxidative stress. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl 1):S15–S23. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel-Kader R, Hauptmann S, Keil U, et al. Stabilization of mitochondrial function by Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) Pharmacol Res. 2007;56(6):493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Költringer P, Langsteger W, Eber O. Dose-dependent hemorheological effects and microcirculatory modifications following intravenous administration of Ginkgo biloba special extract EGb 761®. Clin Hemorheol. 1995;15(4):649–656. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramassamy C, Christen Y, Clostre F, Costentin J. The Ginkgo biloba extract, EGb 761®, increases synaptosomal uptake of 5-hydroxytryptamine: in-vitro and ex-vivo studies. J Pharmacy Pharmacol. 1992;44(11):943–945. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshitake T, Yoshitake S, Kehr J. The Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® and its main constituent flavonoids and ginkgolides increase extracellular dopamine levels in the rat prefrontal cortex. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159(3):659–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehske CJ, Leuner K, Müller WE. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) influences monoaminergic neurotransmission via inhibition of NE uptake, but not MAO activity after chronic treatment. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapin JR, Lamproglou I, Drieu K, DeFeudis FV. Demonstration of the “anti-stress” activity of an extract of Ginkgo biloba (EGb 761®) using a discrimination learning task. Gen Pharmacol. 1994;25(5):1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcilhac A, Dakine N, Bourhim N, et al. Effect of chronic administration of Ginkgo biloba extract or Ginkgolide on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the rat. Life Sci. 1998;(25):2329–2340. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00214-8. 62: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jezova D, Duncko R, Lassanova M, Kriska M, Moncek F. Reduction of rise in blood pressure and cortisol release during stress by Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761®) in healthy volunteers. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;53(3):337–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ICH International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for the Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use . Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guideline. Geneva: ICH; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer‘s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer‘s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Román GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular Dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahoney R, Johnston K, Katona C, Maxmin K, Livingston G. The TE4D-Cog: a new test for detecting early dementia in English-speaking populations. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(12):1172–1179. doi: 10.1002/gps.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YS, Nibbelink DW, Overall JE. Factor structure and scoring of the SKT test battery. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49(1):61–71. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199301)49:1<61::aid-jclp2270490109>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erzigkeit H. SKT Manual A Short Cognitive Performance Test for Assessing Memory and Attention Concise version. Castrop-Rauxel: Geromed; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sunderland T, Hill J, Mellow A, et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer’s disease: a novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):725–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb02233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mega MS, Masterman DM, O’Connor SM, Barclay TR, Cummings JL. The spectrum of behavioural responses to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(11):1388–1393. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.11.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Napryeyenko O, Borzenko I, for the GINDEM-NP Study Group Ginkgo biloba special extract in dementia with neuropsychiatric features. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2007;57(1):4–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummings JL, Mackell J, Kaufer D. Behavioral effects of current Alzheimer’s disease treatments: a descriptive review. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gauthier S, Loft H, Cummings J. Improvement in behavioural symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease by memantine: a pooled data analysis. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):537–545. doi: 10.1002/gps.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodda J, Morgan S, Walker Z. Are cholinesterase inhibitors effective in the management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease? A systematic review of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine. Int Psychogeriat. 2009;21(5):813–824. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banerjee S, Smith SC, Lamping DL, et al. Quality of life in dementia: more than just cognition. An analysis of associations with quality of life in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):146–148. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, et al. What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(1):15–24. doi: 10.1002/gps.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo JG, Turró-Garriga O, López-Pousa S, Vilalta-Franch J. Factors related to perceived quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the patient’s perception compared with that of caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(6):585–594. doi: 10.1002/gps.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agüera-Ortiz L, Frank-García A, Gil P, Moreno A, on behalf of the 5E Study Group Clinical progression of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease and caregiver burden: a 12-month multicenter prospective observational study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(8):1265–1279. doi: 10.1017/S104161021000150X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Beck TL, Evans DA. Influence of behavioral symptoms on rates of institutionalization for persons with Alzheimer‘s disease. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, Lousberg R, Jaspers N, Verhey FRJ. A prospective study of the effects of behavioral symptoms on the institutionalization of patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005;17(4):1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205002292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]