Abstract

The efficient total synthesis of the recently described natural substance largazole (1) and it’s active metabolite largazole thiol (2) is described. The synthesis required eight linear steps and proceeded in 37% overall yield. It is demonstrated that largazole is a pro-drug, that is activated by removal of the octanoyl residue from the 3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid moiety to generate the active metabolite largazole thiol (2) which is an extraordinarily potent Class I histone deacetylase inhibitor. Synthetic largazole and the largazole thiol (2) have been evaluated side-by-side with FK228 and SAHA for inhibition of HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 6. Largazole and largazole thiol were further assayed for cytotoxic activity against a panel of chemoresistant melanoma cell lines and it was found that largazole is substantially more cytotoxic than largazole thiol; this difference being attributed to differences in cell permeability of the two substances, respectively.

Introduction

Largazole (1) is a densely functionalized macrocyclic depsipeptide, recently isolated from the cyanobacterium Symploca sp. by Luesch and co-workers.1 This natural product exhibits exceptionally potent and selective biological activity, with two- to ten-fold differential growth inhibition in a number of transformed and non-transformed human- and murine-derived cell lines. The remarkable selectivity of this agent against cancer cells prompts particular interest in the mode of action of this newly discovered substance and its value as a potential cancer chemotherapeutic.

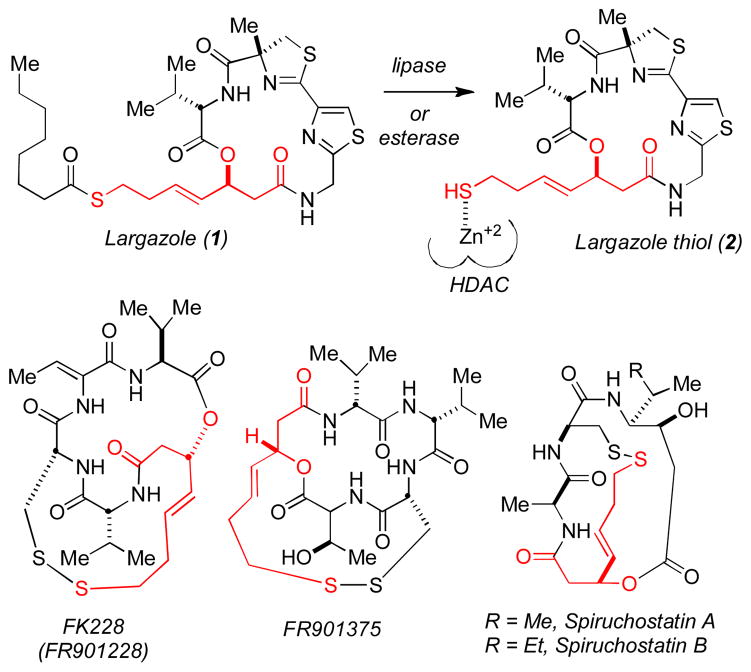

In their isolation paper, Luesch, et al. stated that “the 3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid unit in 1 is unprecedented in natural products.”1 In contrast to this assertion, the (S)-3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid, is in fact an essential motif in several cytotoxic natural products including FK228 (FR901228),2 FR901375,2 and spiruchostatin3 (Figure 1), all of which are known histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi).4,5

Figure 1.

Structure of largazole (1), largazole thiol (2) and several known macrocyclic HDACi natural products containing the (S)-3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid moiety.

The histone deacetylase enzymes are zinc metalloenzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of acetylated lysine residues in chromatin, and thereby regulate transcription in eukaryotic cells.8,9 Their selective inhibition has recently become a major area of research in cancer chemotherapy.10 To date, eighteen HDACs have been identified, which are generally divided into four classes based on sequence homology to yeast counterparts.11 With respect to cancer therapy, there is an emerging consensus that Class I HDACs are clinically relevant and that the undesirable toxicity associated with the first generation of HDAC inhibitors may be related to Class indiscriminancy. As a result, our laboratories have recently initiated programs aimed at the synthesis and modification of peptide- and depsipeptide-based HDACi with the objective of optimizing structures for Class- and even isoform-specific inhibition.

The three natural substances FK228, FR901375 and spiruchostatin, are all activated in vitro and in vivo by reductive cleavage of a disulfide bond to expose the free sulfhydryl residue of the pendant (S)-3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid moiety that coordinates to the active-site Zn+2 residue of the HDACs resulting in a potent inhibitory effect.12 Given that largazole contains this well-known Zn+2-binding arm common to FK228, FR901375 and spiruchostatin, it seemed evident to us that largazole is simply a pro-drug that would thus be expected to be activated by hydrolytic removal of the octanoyl residue by cellular lipases and/or esterases to produce the putative cytotoxic species 2 (the “largazole thiol”). Two laboratories have previously demonstrated that thioester analogues of FK228 retain their antiproliferative activity in cell-based assays.13 As part of our program on the synthesis and chemical biology of FK228 and analogs,14 we report herein, an efficient total synthesis of largazole, the largazole thiol (2) and demonstrate that 2 is an extraordinarily potent HDACi.

Results and Discussion

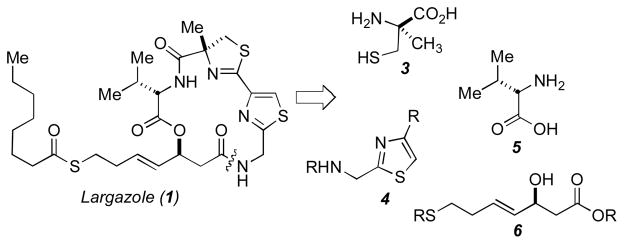

We envisioned disconnection of the macrocycle to the four key subunits illustrated in Figure 2; that is, α-methyl cysteine (3), thiazole (4), (S)-valine (5), and (S)-3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid (6). Given the ready accessibility to these building blocks from prior synthetic15 efforts,14,16 the underlying synthetic challenge turned out to be the macrocyclization strategy. Due to the anticipated susceptibility of the β-carboxylate linkage to undergo elimination, our initial efforts focused on installing this linkage last. However, all methods, both direct (macrolactonization via Yamaguchi, Mukaiyama, Keck, and Shiina) and indirect (inversion via Mitsunobu) failed to provide the desired macrocycle. An additional attempt at closure of the macrocyclic depsipeptide ring via a late-stage thiazoline-forming reaction also failed to provide the desired macrocyclic product. Thus, we turned to a strategy involving early installation of the ester and subsequent closure about the least-hindered amide bond.

Figure 2.

Synthetic strategy to assemble largazole.

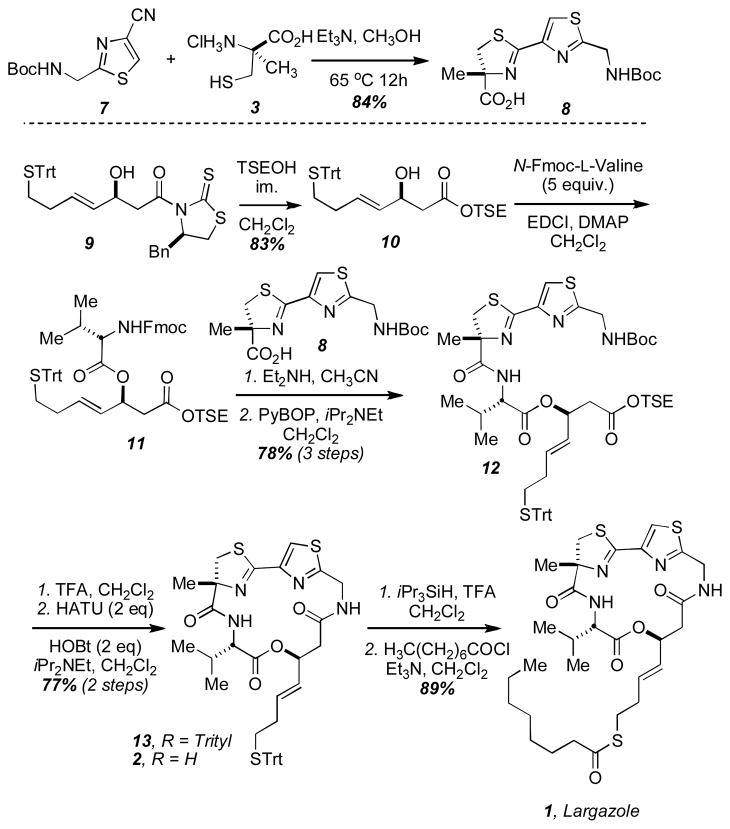

We were able to readily access the necessary α-methyl cysteine subunit with the requisite (R)-stereochemistry via the Pattenden modification of the Seebach protocol on L-cysteine methyl ester (Scheme 1).17 Alternatively, we obtained α-methyl serine as a generous gift from Ajinomoto Co., Japan, and converted this substance into α-methyl cysteine by a published procedure.18 Gram quantities of this amino acid was obtained in high enantiomeric purity and was condensed with the known nitrile (7)19 to provide the thiazoline-thiazole subunit (8) in high yield.

Scheme 1.

The total synthesis of largazole (1) and largazole thiol (2).

We have previously developed a new synthetic route to the β-hydroxy acid (10) based on a Noyori asymmetric transfer hydrogenation protocol.14a In the present work, we found that a recently published synthesis of this subunit to also be expedient and high yielding.21 Thiazolidinethione (9) was treated with 2-trimethylsilylethanol to provide the TSE-protected acid (10), which was subsequently coupled to N-Fmoc-L-valine to afford 11. Due to the sluggish reactivity of allylic alcohol 10, we found it necessary to use an excess (5 equivalents) of this commercially available amino acid. Removal of the Fmoc group and PyBOP-mediated coupling to the thiazoline-thiazole carboxylic acid (8) furnished the acyclic precursor (12).

Cyclization was effected under high dilution in the presence of two equivalents each of HOBt and HATU furnishing the desired macrocycle 13 in 77% isolated yield from 12. Removal of the S-trityl protecting group was accomplished with iPr3SiH and TFA to furnish an authentic sample of the largazole thiol (2) in excellent yield.

Acylation of 2 with octanoyl chloride under standard conditions afforded synthetic largazole in 89% yield from 13. The spectroscopic data (1H NMR, 13C NMR and HRMS) for the synthetic substance were in excellent agreement with that published for the natural product (see Supporting Information).1

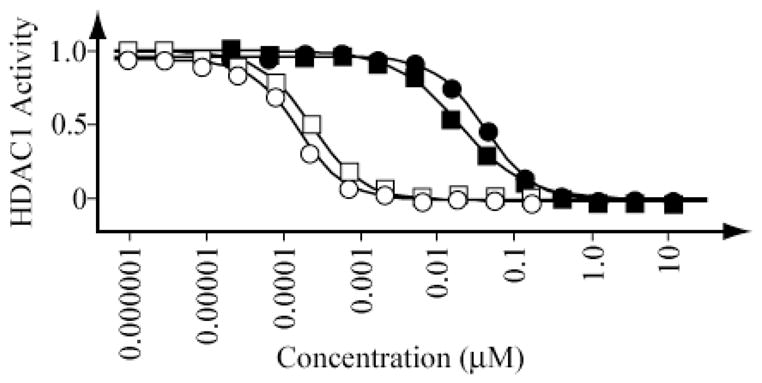

We next interrogated the biochemical activity of synthetic largazole (1) and the largazole thiol (2) against HDACs 1, 2, 3 and 6 for which we have developed robust, kinetic biochemical assays. To measure the inhibitory effect on deacetylase function in vitro, we optimized a continuous kinetic biochemical assay miniaturized to 384-well plate format. In this assay, purified, full-length HDAC protein (HDAC1 1.67 ng/μL, HDAC2 0.067 ng/μL, HDAC3/NCor2 0.033 ng/μL, HDAC6 0.67 ng/μL; BPS Biosciences) was incubated with a commercially available fluorophore-conjugated substrate at a concentration equivalent to the substrate Km (Upstate 17–372; 6 μM for HDAC1, 3 μM for HDAC2, 6 μM for HDAC3/NCoR2 and 20 μM for HDAC6). As presented in Figure 1, largazole thiol is an extraordinarily potent inhibitor of HDAC1 and HDAC2 (Ki = 70 pM).

The parent natural product largazole itself on the other hand, is a comparatively weak HDAC inhibitor with potency approximating the non-selective pharmaceutical product SAHA (Vorinostat; Merck Research Laboratories). In fact, the measurement of potency obtained in these studies of largazole define the maximal possible HDAC inhibitory effect. That is, even a trace contamination of largazole thiol or free thiol liberated under aqueous assay conditions or by trypsin (present in this enzyme-coupled reaction) could account for the substantial decrease in enzyme potency observed.

Detailed studies of FK228 isoform selectivity by our laboratories previously identified a strong bias favoring the Class I enzymes, HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3, over the Class IIb enzyme, HDAC6.14b Similarly, the active depsipeptide largazole thiol (2) exhibits substantial potency against HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 in the picomolar range (Table 1). Indeed, this degree of inhibitory potency against HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 is, to the best of our knowledge, unprecedented. Only FK228 itself has HDACi potency approaching that of 2.

Table 1.

HDAC inhibitory activity (Ki; nM) of largazole (1) and largazole thiol (2) as compared to pharmaceutical HDAC inhibitors.

| Compound | HDAC1 | HDAC2 | HDAC3 | HDAC6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| largazole (1) | 20 | 21 | 48 | > 1000 |

| largazole thiol (2) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 25 |

| FK228a | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 35 |

| SAHA | 10 | 10 | 15 | 9 |

The FK228 sample used in this study was synthesized in these laboratories14a and purified by PTLC to homogeneity.

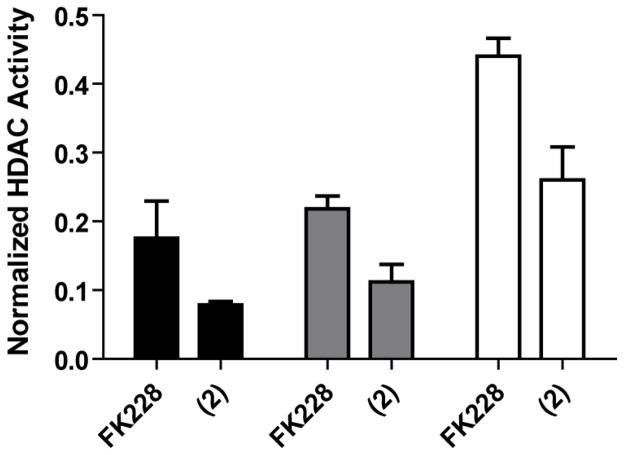

Comparative profiling of FK228 and the largazole thiol (2) demonstrates superior inhibitory potency of the thiol derivative against HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3 (Figure 4). The comparatively diminished potency of largazole itself in these homogeneous assays supports the hypothesis of pro-drug activation of largazole, the specific catalysis of which is the focus of our immediate follow-up studies.

Figure 4.

Comparative profiling of FK228 and the largazole thiol (2). Dose-ranging studies of FK228, largazole and the largazole thiol were performed against Class I HDAC proteins using the described kinetic, homogeneous assay (see Supporting Information). As a comparative measure of potency, compounds were studied in triplicate at a standard concentration (0.6 nM). Averaged data are presented for inhibition of HDAC1 (black), HDAC2 (gray) and HDAC3/NCoR2 (white). Error bars reflect one standard deviation from the mean.

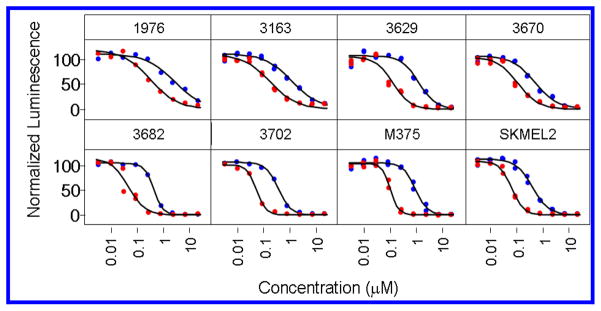

We have initiated studies aimed at determining the potential utility of largazole as a potential HDAC inhibitor-based therapeutic agent. This work comprises studies of physiochemical properties, metabolic stability in serum and liver microsomes and pharmacokinetics in rodents. Immediately, we have initiated studies to determine the antineoplastic effects of largazole (1) and the largazole thiol (2) on cultured human cancer cells. Predicting a potent anti-proliferative effect of largazole based on the biochemical potency for Class I HDACs as described above, we selected a panel of malignant melanoma cell lines for study due to the typically extreme chemoresistance of this tumor. As demonstrated in Figure 5, largazole exhibits sub-micromolar inhibitory effect on melanoma cell proliferation. Importantly, largazole has a consistent, superior potency (IC50 45 nM – 315 nM) compared to largazole thiol (IC50 360 nM – 2600 nM).22

Figure 5.

Antiproliferative effects of largazole (red) and largazole thiol (blue). Effects on cell viability were evaluated using a panel of human malignant melanoma cell lines, using the standard, surrogate measurement of ATP content (Cell TiterGlo; Promega) in 384-well plate format. Replicate measurements were normalized to vehicle-only controls and IC50 calculations were performed by logistic regression (Spotfire DecisionSite). Largazole demonstrates a potent antiproliferative effect (IC50 45 nM – 315 nM) compared to largazole Thiol (IC50 360 nM – 2600 nM).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have completed an efficient total synthesis of largazole (1) in eight linear steps and 37% overall yield, and its active metabolite, the largazole thiol (2) in seven linear steps. This serves to corroborate the structure assigned by Luesch.1 The synthesis recorded here, provided 12 milligrams of synthetic largazole and 19 milligrams of largazole thiol on the first pass and should be readily scaleable to gram-quantities. This amount of synthetic material has allowed for further investigation of the biological activity of this potential cancer chemotherapeutic.

We have demonstrated that largazole is in fact a pro-drug, which must be converted to its active form, free-thiol 2. The combination of cap group and zinc-binding motif present in this thiol provide the most potent and selective HDACi reported to date. The octanoyl residue in largazole apparently serves a dual role, imparting better cell-permeability and allowing facile presentation of the free thiol within the cell. We attribute the observed inverse difference in cytotoxicity to the superior cell-permeability of the thioester (1) as compared to the thiol (2). These studies reveal that numerous opportunities exist for capitalizing on the masked thiol pro-drug manifold inherent in 1, and may be very useful in the design and development of potent and therapeutically useful agents that target inhibition of HDAC’s. Since FK228, FR901375 and spiruchostatin mask the common and key 3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid unit as a reductively labile disulfide,23 other protect and release strategies for exploiting this potent zinc-binding arm in the context of new molecular scaffolds is readily apparent. In addition, the molecular scaffold of largazole provides yet another macrocyclic template24 from which a myriad of potentially active and isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors might be designed and synthesized. Studies along these lines are under investigation in these laboratories.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of HDAC1 by largazole (filled circles), largazole thiol (open circles), SAHA (filled squares) and FK228 (open squares).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Colorado State University Cancer Supercluster for financial support (to RMW and AB). JEB acknowledges support by grants from the Burroughs-Wellcome Foundation and National Cancer Institute (1K08 CA128972-01A1). This project has been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute’s Initiative for Chemical Genetics, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. N01-CO-12400 (NW, SLS and JEB). Mass Spectra were obtained on instruments supported by the NIH Shared Instrument Grant GM49631. We thank Ajinomoto Co., for the generous gift of α-methylserine which was also deployed to construct α-methylcysteine utilized in this study.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Complete experimental details for the synthesis of largazole (1) and largazole thiol (2). Experimental details are provided for the HDAC inhibition assays. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Taori K, Paul VJ, Luesch H. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1806–1807. doi: 10.1021/ja7110064. subsequent to the submission of the present manuscript on May 6, 2008, Luesch, et al. independently published a distinct synthesis of largazole; see: Ying Y, Taori K, Kim H, Homg J, Luesch H. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:0000. doi: 10.1021/ja8013727. (published on-line May 29, 2008)

- 2.(a) Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. 03141296. Jpn Kokai Tokkyo Koho JP. 1991; (b) Ueda H, Nakajima H, Hori Y, Fujita T, Nishimura M, Goto T, Okuhara M. J Antibiot. 1994;47:301. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shigematsu N, Ueda H, Takase S, Tanaka H. J Antibiot. 1994;47:311. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ueda H, Manda T, Matsumoto S, Mukumoto S, Nishigaki F, Kawamura I, Shimomura K. J Antibiot. 1994;47:315. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masuoka Y, Nagai A, Shin-ya K, Furihata K, Nagai K, Suzuki K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:41. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsend PA, Crabb SJ, Davidson SM, Johnson PWM, Packham G, Ganesan A. The bicyclic depsipeptide family of histone deacetylase inhibitors. In: Schreiber SL, Kapoor TM, Wess G, editors. Chemical Biology. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; Weinheim, Germany: 2007. pp. 693–720. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ref. 1b substantially corrected the error in ref. 1a with respect to the novelty of the (S)-3-hydroxy-7-mercaptohept-4-enoic acid moiety and also reported IC50 HDAC inhibitory data for Largazole.

- 8.Somech R, Israeli S, Simon A. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:461. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Miller TA, Witter DJ, Belvedere S. J Med Chem. 2003;46:5097. doi: 10.1021/jm0303094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Moradei O, Maroun CR, Paquin I, Vaisburg A. Curr Med Chem; Anti-Cancer Agents. 2005;5:529. doi: 10.2174/1568011054866946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2006;5:769. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minucci S, Pelicci PG. Nature Rev Cancer. 2006;6:38. doi: 10.1038/nrc1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Science. 1996;272:408. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Grozinger CM, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Johnstone RW. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2002;1:287. doi: 10.1038/nrd772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Yoshida M, Kijama M, Akita M, Beppu T. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshida M, Hoshikawa Y, Koseki K, Mori K, Beppu T. J Antibiot. 1990;43:1101. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Or YS, Verdine GL, Keegan M. Preparation of Metabolite Derivatives of the HDAC Inhibitor FK228. WO 2007061939 PCT Int Appl. 2007; (b) Yurek-George A, Cecil ARL, Mo AHK, Wen S, Rogers H, Habens F, Maeda S, Yoshida M, Packham G, Ganesan A. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5720. doi: 10.1021/jm0703800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Johns DM, Greshock TJ, Noguchi Y, Williams RM. Org Lett. 2008;10:613. doi: 10.1021/ol702957z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Greshock TJ, West N, Schreiber SL, Bradner JE, Williams RM. unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

- 15. .

- 16.(a) Li KW, Wu J, Xing W, Simon JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7237. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen Y, Gambs C, Abe Y, Wentworth P, Janda KD. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8902. doi: 10.1021/jo034765b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yurek-George A, Habens F, Brimmell M, Packham G, Ganesan A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1030. doi: 10.1021/ja039258q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Jeanguenat A, Seebach D. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1991;1:2291. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mulqueen GC, Pattenden D, Whiting DA. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:5359. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith ND, Goodman M. Org Lett. 2003;5:1035. doi: 10.1021/ol034025p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Videnov G, Kaiser D, Kempter C, Jung G. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 1996;35:1503. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lange UEW, Schäfer B, Baucke D, Buschmann E, Mack H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:7067. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yurek-George A, Habens F, Brimmell M, Packham G, Ganesan A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1030. doi: 10.1021/ja039258q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Note added in revision. We note that there are significant discrepancies between that reported in ref. 1b and our results reported here with respect to the biochemical HDAC inhibitory data obtained and supporting mechanism of action. The biochemical data provided herein, reflect activity in highly robust, miniaturized homogeneous assays with Z′ calculations compatible with high-throughput screening. In this assay, we observe high concordance with published, kinetic measurements of enzyme inhibition (Ki). Thus, the accuracy of our reported HDAC inhibitory data would be expected to be markedly improved. This is important due to our observation of the unusual, perhaps unprecedented potency of largazole thiol for HDAC1 and the direct comparison provided to FK228. The data offered in ref. 1b are IC50 data, which have substantial variation between assays and are thus of limited utility and extensibility. We also note that the present synthesis is significantly higher yielding than that reported in 1b.

- 23.Furumai R, Matsuyama A, Kobashi N, Lee KH, Nishiyama M, Nakajima H, Tanaka A, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For several naturally occurring macrocyclic HDAC inhibitors, see: Singh SB, Zink DL, Polishook JD, Dombrowski AW, Darkin-Rattray SJ, Schmatz DM, Goetz MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8077.Nakao Y, Yoshida S, Matsunaga S, Shindoh N, Terada Y, Nagai K, Yamashita JK, Ganesan A, van Soest RWM, Fusetani N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602047.Kijima M, Yoshida M, Sugita K, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22429.Tsuji N, Kobayashi M, Nagashima K, Wakisaka Y, Koizumi K. J Antibiot. 1976;29:1. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1.