Abstract

Substantial literature suggests that diverse biological, psychological, and sociocultural mechanisms account for differences by race and ethnicity in the experience, epidemiology, and management of pain. Many studies have examined differences between Whites and minority populations, but American Indians (AIs), Alaska Natives (ANs), and Aboriginal peoples of Canada have been neglected both in studies of pain and in efforts to understand its bio-psychosocial and cultural determinants. This article reviews the epidemiology of pain and identifies factors that may affect clinical assessment and treatment in these populations. We searched for peer-reviewed articles focused on pain in these populations, using PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane, and the University of New Mexico Native Health Database. We identified 28 articles published 1990-2009 in 3 topic areas: epidemiology of pain, pain assessment and treatment, and healthcare utilization. A key finding is that AI/ANs have a higher prevalence of pain symptoms and painful conditions than the U.S. general population. We also found evidence for problems in provider-patient interactions that affect clinical assessment of pain, as well as indications that AI/AN patients frequently use alternative modalities to manage pain. Future research should focus on pain and comorbid conditions and develop conceptual frameworks for understanding and treating pain in these populations.

Perspective

We reviewed the literature on pain in AI/ANs and found a high prevalence of pain and painful conditions, along with evidence of poor patient-provider communication. We recommend further investigation of pain and comorbid conditions and development of conceptual frameworks for understanding and treating pain in this population.

Keywords: American Indians, Alaska Natives, pain, disparities

Introduction

Pain is the most common reason for seeking medical treatment in the U.S. and the second most common reason for ambulatory care visits.52 More than 20% of physician visits and 10% of drug sales are attributed to pain.48 The annual cost of pain includes more than $100 billion for pain-related healthcare, compensation, and litigation, as well as $61.2 billion for lost productivity.37, 61

As a complex phenomenon described in terms of both sensory and emotional experiences,49 pain is extremely variable even among members of a homogenous population. A considerable body of literature suggests that diverse biological, psychological, and sociocultural mechanisms contribute to disparities by race and ethnicity in pain prevalence, perception, and reporting.15, 16, 27, 35, 51, 57 Additionally, studies have shown that providers may react differently to pain reported by patients of varying racial and ethnic characteristics.2, 22

The National Institutes of Health defines health disparities as “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups.” 19 A higher prevalence of risk factors for illness, such as lower socioeconomic status, poor health habits, and inadequate access to healthcare services, predisposes minority groups to suffer a higher burden of pain.1 Over the past decade, a systematic effort has focused on understanding the reasons for such differences in the pain experience of Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics. However, American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs) and Aboriginal peoples of Canada have received much less attention. As a relatively small minority group, they are frequently excluded from research studies.

Nevertheless, a modest literature on pain in these groups, predominantly AI/ANs, is slowly accumulating. Relevant articles appear in journals devoted to pain, but are also scattered through other specialty journals. In addition, publications on related topics, such as use of alternative medicine, may also report notable findings about pain and its management. Considered together, such work provides important insights about how the prevalence and experience of pain may vary in these populations; it may also illuminate potentially unique barriers to care with implications for both research and clinical practice.

Accordingly, we review the literature on pain in AI/ANs and Aboriginal people of Canada to 1) portray their pain experiences; 2) describe the epidemiology of pain; and 3) discuss factors that may affect the clinical assessment and treatment of pain. With 2 exceptions, the publications describe AI/AN populations, so we place our findings in the context of the related literature on healthcare delivery systems in the U.S. Finally, we draw conclusions for future research avenues and make recommendations for improving healthcare delivery.

We follow the convention of the U.S. Census Bureau in defining AI/ANs as “people having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America and who maintain tribal affiliation or community attachment.” 64 While our grouping of AI/ANs into a single category follows the common research convention, we acknowledge a substantial degree of heterogeneity among these population groups. We compensate, whenever possible, by identifying the specific tribal group for the studies we review.

Healthcare Context for American Indians and Alaska Natives

The 2.9 million people who report exclusive and the 1.6 million who report partial AI/AN ancestry comprise 1.5% of the total U.S population.65 They are a diverse group, residing in 35 states and organized into 564 federally recognized tribes.66 Only 34% of AI/ANs live on federal reservations, with the remainder residing mainly in urban settings. In both contexts, the indigenous peoples of the U.S. are disproportionately poor. More than a quarter have incomes that fall below the federal poverty level, compared with 9% of U.S. Whites.69

The U.S. federal government has a trust responsibility, formalized in treaties and other agreements, to provide healthcare without cost to members of federally recognized tribes.26 Since 1955 this responsibility has been fulfilled by the Indian Health Service (IHS), a complex federally mandated program that delivers primary healthcare to reservation communities, either directly or through contracted tribal services. However, the IHS provides care only to about 1.5 million AI/ANs. Some are ineligible for services because they are not members of federally recognized tribes, while others reside far from IHS facilities. An estimated one-third of AI/ANs younger than age 65 lack both private insurance and access to care through the IHS,20 compared to 16.7% for all people under 65 years of age in the U.S.23 Further, the IHS has been chronically underfunded and is seldom equipped to provide specialty services, such as care for chronic pain.10 While a parallel system of more than 30 non-IHS Indian health facilities exists in urban areas to provide care to urban AI/ANs, this system is similarly underfunded. Given such a combination of individual and contextual factors, we anticipated that our literature review would detect problems with the assessment and treatment of pain in AI/ANs.

Methods

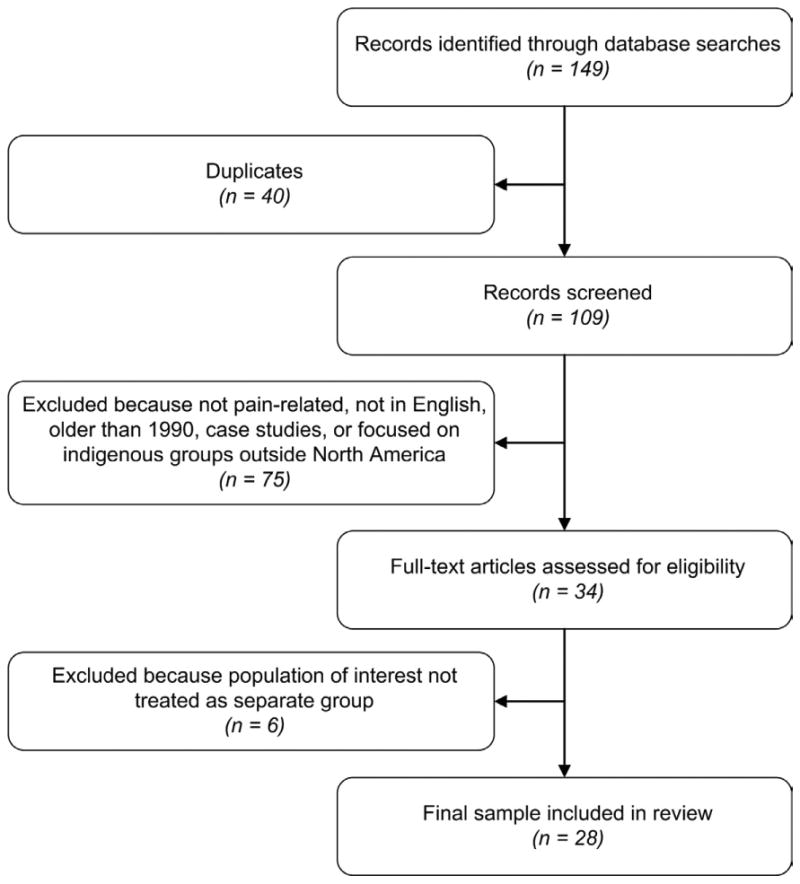

We searched for peer-reviewed articles using the following databases: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Collaboration Reviews, and the University of New Mexico Native Health Database. In our search strategy we used the key term “pain” in combination with the terms “American Indian,” “Native American,” “Alaska Native,” and “First Nation” (a term commonly used to designate the Aboriginal people of Canada). Additional references were obtained from the bibliographies of articles identified in this way. We limited our selection based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) studies focusing substantively on issues related to the pain experience, epidemiology of pain, pain management, and healthcare utilization due to pain symptoms and painful conditions; and 2) studies reporting results for the indigenous populations of the U.S. and Canada. We excluded articles in a language other than English and those published before 1990. We also excluded all case reports, as well as studies that grouped AI/ANs or Aboriginal Canadians with one or more additional racial or ethnic groups for analyses, usually to create an undifferentiated “Other” category; such studies would have prevented us from drawing population-specific conclusions. Articles were then grouped in the categories of epidemiology of pain; pain management (i.e., assessment and treatment of pain); and healthcare access and utilization. Our selection strategy is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Article selection process.

Results

Our initial search using key terms yielded a total of 149 citations. Forty were duplicates, leaving 109 journal articles. Of these, we excluded 75 articles because they were not substantially related to pain, were published before 1990, were case reports, were written in a language other than English, or sampled indigenous groups outside of North America. Of the 34 remaining articles, we excluded 6 because they did not consider AI/ANs as a separate group. In the final sample of 28 articles, we identified 12 articles on the epidemiology of pain and painful conditions; 10 on issues in pain assessment and treatment, and 6 on healthcare access and utilization (see Table 1). In the next sections we summarize themes and notable results in each of these 3 areas.

Table 1. Summary of Articles Retrieved.

| First Author | Year | Study Population | Study Design and Aims | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology of Pain | ||||

| Barnabe C | 2008 | Adult First Nations and White Manitobans (Canada) | Design: Cross-sectional analysis of arthritis burden and healthcare utilization using 3 separate data sources: (1) physician claims from Population Health Research Data Repository for First Nations Manitobans, (2) self-report data from Manitoba First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey, and (3) retrospective review of clinical data from an Arthritis Center serving the population. | 21% of First Nations people reported arthritis. |

| Aim: Estimate prevalence and severity of rheumatoid arthritis in First Nations peoples. | Compared with all Manitobans seen in Arthritis Center, First Nations patients had 2-4 times higher likelihood of inflamatory disease | |||

| Barnes PM | 2005 | Adult U.S. population | Design: CDC report on health characteristics of AI/AN adults. Data obtained from 1999-2003 Annual Family Core and Sample Adult Core components of the National Health Interview Surveys. | Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, AI/ANs reported a higher prevalence of recurrent headaches (29.0% vs.22.9%) and neck pain (20.7% vs. 15.3%). |

| Aim: Compare health status indicators for AI/AN with other U.S. racial/ethnic groups. | ||||

| Bernabei R | 1998 | 13,625 adults > 65 years, including 276 AIs with cancer, admitted to Medicaid/Medicare certified nursing homes | Design: Secondary data analysis of Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology (SAGE) database | AIs and all minority patients reported lower levels of daily pain. |

| Aim: Evaluate 7-day prevalence of daily pain and adequacy of pain management. | Race was an independent predictor for pain. After adjusting for age, marital status, and comorbidities, no significant association was found. | |||

| AI patients received analgesics as frequently as White patients. | ||||

| Buchwald D | 2005 | 3,084 AIs aged 15-54 years from the Southwest and Northern Plains | Design: Cross-sectional survey of probability sample | Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder was 16% in the Southwest and 14% in the Northern Plains. |

| Aim: Estimate association between lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized widespread pain over a 4-week period. | Women were twice as likely as men to have posttraumatic stress disorder. | |||

| Pain was higher among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder, as demonstrated by 10% lower scores in the bodily pain subscale of the Short Form-36 (lower scores indicate more pain). | ||||

| Chowdhury PP | 2008 | Adult U.S. population ≥ 18 years | Design: Population-based study using Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System national database | AI/ANs more often reported poor quality of life, physical distress (physical illness or injury), mental distress (stress, depression, or problems with emotions) and activity limitations than all other racial/ethnic groups. |

| Aim: Evaluate self-reported health-related quality of life among minority populations during 30 days before study interview. | Frequent pain was reported by 15% of AI/ANs; almost twice as likely than White subjects (OR=1.62 [95% CI = 1.19-2.21]). | |||

| AI/ANs had the highest prevalence of depresive (11%) and anxiety symptoms (19%) of all racial/ethnic groups. | ||||

| Deyo RA | 2006 | Adult U.S. population ≥ 18 years | Design: Secondary data analysis of 2 U.S. national population-based studies: the National Health Interview survey and the National Ambulatory Medical Care survey. | AI/AN have the highest prevalence of low back pain among all racial groups. |

| Aim: Estimate 3-month prevalence of low back pain and physician visit rates for back pain. | Prevalence of low back pain for AI/ANs is 35%, compared to 26% for the U.S. general population. | |||

| Prevalence of low back pain is significantly associated with level of education and income. | ||||

| Ferucci AD | 2005 | Adult AI/AN patients | Design: Review article | High prevalence rates of rheumatoid arthrtis in AI/ANs, compared to a rate of 1% for U.S. general population. |

| Aim: Review epidemiology and serologic features of rheumatoid arthritis among U.S. AI/ANs. | Rates between 1.4% and 7.1% for Tinglit, Yakima, Pima, and Mille Lacs Chippewa Band tribes. | |||

| Disease in AI/ANs has early onset and more rapid progress compared to U.S. general population. | ||||

| Leake J | 2008 | 349 preschool children aged 2-6 years and their caregivers in the Inuvik Region of Canada | Design: Cross-sectional community-based study to assess oral health status and determine risk factors for poor oral health through interviews with caregivers | High prevalence (66%) of dental caries in First Nations preschool children, with 12% needing urgent care. |

| Aim: Determine the prevalence and risk factors for dental caries among First Nation preschool children. | Parents reported significant pain associated with dental caries. | |||

| Mauldin J | 2004 | AI children and adolescents < 19 years from Oklahoma area and Northern Plains (Crow, Blackfeet, Sioux) | Design: Secondary data analysis of Indian Health Service patient registration database from 1998 to 2000, for Oklahoma City and Billings Area. | Crude prevalence of juvenile rheumatoid arthrtis in Oklahoma area = 53/100,000; in Billings area = 115/100,000. |

| Aim: Estimate crude prevalence of juvenile/reumatoid arthritis. | ||||

| Quandt SA | 2009 | Adults > 59 years in 2 U.S. rural counties | Design: Cross-sectional community-based study comparing oral health in older African Americans, Whites, and AI adults in the U.S. | AIs and African Americans reported poor oral health more frequently than Whites. |

| Aim: Determine prevalence of periodontal disease and poor oral health. | AIs had highest frequency of periodontal disease, bleeding gums, and oral pain. | |||

| Rhee H | 2000 | 6,072 U.S. students in grades 7-12 | Design: Secondary data analysis of National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health database | AI/AN adolescent students had a higher prevalence of recurrent headaches than non-Hispanic Whites (35.6% vs. 30.0%). |

| Aim: Determine racial differences for prevalence and predictors over 12 months for recurrent headaches. | ||||

| Rhee H | 2005 | 18,722 U.S. students in grades 7-12 | Design: Secondary data analysis of National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health database | Compared to non-Hispanic White students, AI/ANs had a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal pain (34.5% vs. 29.7%) and chest pain (10.0% vs. 3.6%). |

| Aim: Evaluate racial differences in the 12-month prevalence of physical symptoms. | ||||

| Pain Assessment and Treatment | ||||

| Barkwell D | 2005 | 18 Ojibway patients, caregivers, and healers from a reserve in Canada and 13 healthcare profesionals serving these patients | Design: Qualitative study using Grounded Theory | Pain is conceptualized in the context of physical sensations and emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of the individual. |

| Aim: Describe conceptualization of cancer pain. | Patients prefer not to talk about pain because “talking about it makes it real.” | |||

| Burhansstipanov L | 2005 | AI/AN patient participants in a national Native cancer survivors conference. | Design: Qualitative report | AI/ANs prioritize research that would make pain assessment tools more culturally acceptable. |

| Aim: Prioritize cancer research topics. | ||||

| Elliot BA | 1999 | 89 adult cancer patients and other adults from 4 Ojibwe communities, plus 39 healthcare personnel of unspecified ethnicity | Design: Qualitative study using focus groups | Ojibwe patients reported pain only if severe. |

| Aim: Identify barriers to cancer pain management. | They considered pain an inherent part of cancer that cannot be alleviated. | |||

| Patients and healthcare personnel were concerned about addiction to pain medications. | ||||

| Gaston-Johanson F | 1990 | 153 adult volunteers from White, Hispanic, African American, and AI backgrounds (N=37) | Design: Community-based study | Pain descriptors and severity attributed to each descriptor were similar between groups. |

| Aim: Identify similarities and differences in 78 pain descriptors from the McGill Pain Questionnaire. | ||||

| Kramer BJ | 2002 | 56 urban Choctaw, Navajo, and Sioux adults in Los Angeles experiencing joint pain at the time of interview | Deisgn: Community-based study using in-depth interviews with bilingual interviewers | Vague descriptors such as “ache” are often used to express severe pain symptoms and disability. |

| Aim: Determine descriptors of joint pain. | ||||

| Kramer BJ | 2002 | 56 urban Choctaw, Navajo, and Sioux adults in Los Angeles experiencing joint pain at the time of interview | Design: Community-based study using in-depth interviews with bilingual interviewers | AIs understate serious symptoms; verbal communication about pain is subtle and underemphasized. |

| Aim: Determine beliefs and self-care strategies for arthritis. | AI patients may have poor coping strategies to control pain. | |||

| Miner J | 2006 | 1,633 emergency department patients in a county hospital in Minnesota, including non-Hispanic Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans, as well as 145 AIs | Design: Prospective observational clinical study | Significant negative correlation between physicians' perception of “exaggerating pain symptoms” and changes in pain scores after treatment. |

| Aim: Determine physician-dependent risk factors associated with pain treatment – specifically, physician perceptions of pain symptom exaggeration. | Of all ethnic/racial groups studied, AIs were the most likely to be perceived by physicians as exaggerating symptoms, and AIs reported the least reduction in pain after treatment. | |||

| AIs were more likely to rate physician-patient interactions as poor than any other racial/ethnic group. | ||||

| Pelusi J | 2005 | AI/AN patient participants in a national Native cancer survivors conference | Design: Qualitative report | AI/ANs have difficulties reducing their pain to a number or to simple descriptors, because pain is conceptualized as a physical, social, and spiritual experience, |

| Aim: Describe common themes in cancer experiences. | ||||

| Stephenson N | 2009 | 66 cancer patients, including 14 AIs from 4 hospitals and 1 cancer center in the Southeastern U.S. | Design: Cross sectional descriptive study | AI patients were more concerned about risk of addition to pain medicines than patients of all other racial/ethnic groups. |

| Aim: Evaluate and identify barriers to cancer pain management, and satisfaction with pain treatment. | ||||

| Strickland CJ | 1999 | 2 Pacific Northwest tribal communities | Design: Qualitative study using in-depth interviews and focus groups | Pain is conceptualized within a broad context of well-being as a function of body, mind, emotion, and spirit. |

| Aim: Study attitudes towards and conceptualization of pain. | ||||

| Healthcare Access and Utilization | ||||

| Buchwald D | 2000 | 869 AI/AN adult patients ≥ 18 years, seen at an urban primary care program | Design: Cross-sectional study | 70% of urban AI/AN primary care patients reported using traditional health practices. |

| Aim: Ascertain use of traditional health practices. | Traditional health practices were used, on average, 26 times per year, and 52% of patients reported that these practices helped their medical condition. | |||

| 31% of patients who used traditional practices reported pain symptoms. | ||||

| Cueva M | 2005 | 477 village-based community health aids and community health practitioners in rural Alaska | Design: Cross-sectional study using a mailed survey with an 84% return rate | Community health practitioners did not have adequate knowledge of cancer pain and felt uncomfortable discussing it. |

| Aim: Evaluate community health practitioners' knowledge and comfort managing patients and providing information about cancer. | ||||

| Ferucci AD | 2008 | 9,968 AI (Navajo from the Southwest) and AN adult patients from 26 communities | Design: Cross-sectional study using audio computer-assisted self-interviews | Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis for ANs = 26.1% and for Southwest AIs = 16.5%. |

| Aim: Determine the prevalence of self-reported diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis, health-related factors (physical activity and chronic medical conditions), and rheumatoid arthritis treatment. | ANs with rheumatoid arthritis reported more use of traditional healing than ANs without rheumatoid arthritis, OR 1.4 (95% CI = 1.0-1.9). | |||

| Kim C | 1998 | 300 Navajo adult ambulatory care clinic patients | Design: Cross-sectional study | 62% of Navajo patients had used Native healers, and 39% used them regularly. |

| Aim: Determine the prevalence of Native healer use by Navajo patients. | Abdominal, back, and chest pain were among the most common reasons for use of Native healers. | |||

| Neff DF | 2007 | Adult AIs seen in a nurse-managed urban health center in Ohio | Design: Retrospective review of administrative database | Most patients were female and uninsured with low income levels. |

| Aim: Describe characteristics of AI patients and most common reasons for seeking care. | The most common reason for seeking care was pain (27.3%). | |||

| Struthers R | 2004 | 866 AI women from 3 rural reservations in Minnesota and Wisconsin participating in the Inter-Tribal Heart Project | Design: Cross-sectional study | Only 68% of AI women would actively seek immediate medical care when experiecing crushing chest pain for more than 15 minutes. |

| Aim: Evaluate behaviors in response to chest pain. | ||||

Note: We did not attempt to standardize the names of tribal groups. Names in this table follow the ones used in individual studies.

Epidemiology of Pain

Among the 12 studies on the prevalence of pain and painful conditions in AI/ANs, 4 focused on non-regional frequent pain or chronic widespread pain; 3 on arthritis; 2 on oral pain; and 1 each on back pain, headache, and cancer pain. Most studies sampled adults, with only 3 limited exclusively to pain in children and adolescents. All but one of the 12 studies in this general topic area concluded that AI/ANs have a higher prevalence of pain and painful conditions than the U.S. general population.

Among the publications on arthritis, a study of Northern Plains children reported a high prevalence of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis among Crow, Blackfeet, and Sioux youth (115 per 100,000). No direct comparisons to children and adolescents of other racial and ethnic groups were made. However, the observed prevalence was 10 times higher than previous reports for the general U.S population.47 Another study addressed the prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis among adults in various tribal populations across the U.S., including the Tlingit in southeast Alaska, the Yakima in central Washington, the Pima in Arizona, and the Mille Lacs Chippewa Band in central Minnesota. This study reported prevalence rates ranging from 1.4% and 7.1%, compared to 1% for the U.S general population.29 A third study, using self-report and clinical data on arthritis among Aboriginal and White patients in Manitoba, Canada, echoed the findings of the 2 U.S studies: Aboriginal patients were twice as likely as Whites to see a care provider for rheumatoid arthritis, degenerative arthritis, and unspecified arthropathy, and were also more likely to suffer from inflammatory disease.6

Four studies focused mainly on the prevalence of specific types of localized pain and identified disparities in pain symptoms. Two population-based studies using U.S national databases found that AI/AN patients report a high prevalence of pain symptoms. In the first study, AI/ANs reported a higher prevalence of low back pain than the general population (35% vs. 26.4%).25 In the second study, AI/ANs reported a higher prevalence of recurrent headaches (22.9% vs. 15.5%) and neck pain (20.7% vs. 15.3%) than Whites.7

Two studies examined the prevalence of specific types of pain among U.S adolescents of all races, using a school-based survey. The first found a significantly higher prevalence of headaches in AIs than in adolescent students of all races (35.6% vs. 30%).58 The second reported a higher prevalence of generalized musculoskeletal pain (34% vs. 29%) and chest pain (10.1% vs. 3.59%) in AI students than in White students.59

We also identified one study that evaluated management of cancer pain in 13,625 patients who were older than age 65 and admitted to Medicare- or Medicaid-certified nursing homes in 5 states. This study, which used self-reported data as well as healthcare providers' behavioral assessments of pain, is the only one in our review that reported a lower unadjusted prevalence of pain symptoms among AI/AN than White respondents. Race was an independent predictor for daily pain, but after adjusting for confounding variables, such as age, marital status, and comorbidities, differences persisted only for African American patients.9

Two epidemiological studies, one of older adults and the other of young children, suggested that health conditions not typically considered major sources of pain for the general population can function as such for AI/ANs. Both found a high prevalence of oral pain. Poor oral health, including periodontal disease and dental caries, was associated with considerable pain, especially for the pediatric group.45, 56

Finally, 2 epidemiologic studies illuminated the comorbidity of pain and psychiatric conditions. A cross-sectional psychiatric survey found that 15% of 3,084 members of reservation communities of the Northern Plains and the Southwestern U.S. met lifetime criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder – twice the rate detected among non-Hispanic Whites.12 This study also found that people with posttraumatic stress disorder reported higher rates of widespread chronic pain than those without posttraumatic stress disorder.12 Similarly, a population-based study of health-related quality of life in U.S. adults found that AI/ANs reported the highest prevalence of frequent body pain (15%) as well as the highest frequency of depressive (11%) and anxiety (19%) symptoms of all racial and ethnic subpopulations.21

Pain Assessment and Treatment

Studies that focus on the clinical assessment and treatment of pain in AI/AN populations are rare; our review identified only 10. Most suggested that AI/AN patients use patterns of medical communication related to pain that distinguish them from their primarily non-Native healthcare providers and may lead to miscommunication.

Two studies drew on in-depth interviews with adult urban AI patients who suffered from chronic joint pain. Both revealed that patients underemphasized pain and disability, describing even severe symptoms and serious joint disease with vague terms such as “ache” or “discomfort.” 42, 43 A third study, however, reached a different conclusion.34 Conducted in non-medical community settings among Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Cherokee Indians, this study found no differences in use of pain descriptors across groups. All respondents associated similar intensities of pain for a set of terms that included “hurt,” “ache,” and “pain.” Notably, however, all participants in this project were volunteers without previous experience of severe pain.34

A study of cancer pain in Ojibwe women noted a culturally-grounded unwillingness to discuss pain at all.5 The researchers identified a common pain response that they labeled “blocking,” described as the closing down of discourse and thought. Patients who used blocking intentionally avoided discussing their pain with care providers because, as one patient explained, “talking about it makes it real.” These patients expressed the conviction that it was the provider's role to perceive and experience the patient's pain in order to treat it. The expectation of such empathy, in their view, reduced the importance of their own communication about pain.5

Although AI/ANs in general appear to underreport pain, one study in an emergency department found that physicians were especially likely to discredit pain complaints from AI/ANs patient who requested pain medication.50 Indeed, AI/ANs were the racial and ethnic group most often perceived as exaggerating distress. Not surprisingly, these patients were also highly likely to describe their interactions with providers as poor, and were less likely than White patients to report adequate pain relief after medical encounters.50

One qualitative study of AI women in the Pacific Northwest identified a conceptual model that the participants used in dealing with the pain experience. They tended to conceptualize pain in a broad context of well-being, understood as a function of mind, body, emotion, and spirit. This model contrasted with their providers' tendency to conceive pain as a purely physical phenomenon that could be treated in isolation from other spheres of life.62 Pertinent to this model, 2 studies resulting from the first Native American Cancer Survivors Conference considered issues of pain assessment in AI/ANs. The first, a synopsis of themes emerging from a discussion among Native patients about living with cancer, reported dissatisfaction with standard pain scales and pain questionnaires. Participants had difficulty reducing pain to a number or capturing it with reference to fixed descriptors; instead, they felt that their pain reflected social and spiritual qualities and not merely physical symptoms.55 The second publication reported priorities for research identified by AI/AN cancer patients, singling out the necessity of improving pain assessment tools by making them more culturally acceptable.13

In the area of pain treatment, 2 studies found that Native patients identified potential opioid addiction as a major concern related to conventional pain treatment, and both noted the respondents' general disbelief in the ability of medications to alleviate pain.28, 60 One was a report on cancer pain in 4 Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota, which also found that clinicians identified their own concerns about inducing addiction (or re-addiction) as a barrier to treating pain in AI patients.28

Healthcare Access and Utilization

A third group of investigations, consisting of 6 research studies, examined healthcare access and utilization, including specific medical interventions for pain. Two of these studies foreground the likelihood that AI/AN patients will receive care from non-physician providers, due in part to financial constraints and regional differences in provider availability. One study included a survey of almost 500 community health practitioners in Alaska, who reported that they often felt confident discussing cancer risk factors or care issues, but had less knowledge and comfort around cancer pain.24 The other study, conducted in an urban, nurse-managed primary care center, found that pain-related issues were the most common reason for seeking care.54

Other studies in this group suggest that AI patients may hesitate to embrace conventional medical interventions for pain. For example, 866 AI women on 3 rural reservations in Minnesota and Wisconsin were asked to predict their response to “crushing chest pain that lasted longer than 15 minutes;” 32% indicated that they would forego seeking immediate professional care, with 23% preferring instead to “sit down and wait until it passed.” 63

Given this skepticism regarding the ability of conventional medicine to treat pain, AI/ANs commonly turn to treatments grouped under the rubric of “traditional” or “Native healing.” Such healing modalities, which typically focus on identifying and responding to the underlying causes of disease (often attributed to spiritual factors) rather than on treating acute conditions,11 may be important to Native people in both urban and rural settings. One study of rural Navajo communities found that 62% of patients received care from “Native healers,” defined as consultation with a “medicine man,” and 39% used such services more than once per year. While this study did not inquire into the type of healer or ceremony that patients used, consultations frequently concerned conditions associated with pain, including arthritis and depression.41 Similar results were obtained in a study of rheumatoid arthritis that reported the use of traditional healing practices in 45% of AN patients and 63% of Navajo patients.30

Reliance on traditional practices may be even more frequent in urban contexts than on reservations. In one survey of 869 urban AI/AN patients in primary care, 70% used traditional health practices such as herbal medicines, “smudging” (burning bundles of aromatic plants to produce smoke), and participating in special healing or sweat lodge ceremonies.11 Pain of relatively indeterminate origin, such as back pain and arthritis, significantly predicted recourse to traditional health practices, which patients reported using an average of 26 times per year.11 Half of the participants described significant improvements in their health in response to traditional practices. Notably, the literature on alternative therapies among AI/AN patients finds that availing oneself of these practices does not preclude use of conventional medical care.4

Discussion

Our review of the scattered literature on pain in AI/ANs and Aboriginal Canadians has yielded meaningful insights and illuminated promising areas for future research. First, all studies that we identified agree that pain symptoms and painful conditions are highly prevalent, with 11 of the 12 epidemiological studies finding a higher prevalence among AI/ANs than in the U.S. general population. A large majority addressed pain in populations with specific medical conditions, while only 4 examined pain per se. Clinical studies that have illuminated issues related to overall pain perception and sensitivity in other populations15, 16, 27, 57 are entirely lacking for Native populations, and research on relationships between pain and comorbid conditions is rare.

Second, although AI/ANs are up to 2 times more likely to abuse opioids, tranquilizers, and amphetamines than non-Hispanic Whites,38 we identified no studies that explored the extent to which any type of substance abuse might represent a response to painful conditions. Investigations of potential relationships between undertreated pain and mental disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder and substance abuse seem promising.

Third, culture may play a key role in the experience of pain for AI/ANs and Aboriginal Canadians, in ways that may carry implications for medical assessment. A body of research indicates that Native patients embrace culturally-grounded health beliefs and values, along with distinctive models of health and illness that distinguish them from their healthcare providers and sometimes result in medical miscommunication.17, 18, 33 Although several studies in our review identified the need for investigations of cultural variation in conceptual models and patterns of communication about pain, we did not find any studies that either addressed the adequacy of available tools for assessing pain or proposed modifications of such tools to fit the needs of Native populations. Because Native people express difficulties in reducing their experience of pain to numerical scores or other abstract scales, we strongly recommend efforts to develop culturally appropriate measurement tools.

Fourth, patient-provider communication emerged as an important area of concern in pain and pain treatment. AI/ANs perceive medical providers as uninterested in their pain, and they lack faith in providers' abilities to treat it. Conversely, medical providers perceive these patients as exaggerating their pain, a perception that detracts from patient-provider interaction.50 The literature on medical interactions involving racial and ethnic minorities has long argued that patients from different cultural backgrounds may interact with medical providers around pain in distinctive ways.3, 40 Such differences have been observed even among people who are assimilated in many other ways into mainstream U.S. society.36 Furthermore, particular tribal populations can bring distinctive communication patterns to the medical encounter, including culturally specific metaphors,39 disease models,8 word usage,68 avoidance norms,18 and narrative styles.14, 31, 32, 46 Taken together, difficulties in communicating about pain in the clinical setting appear to contribute to inadequate pain management among minority patients in general, and AI/ANs in particular.2, 3 Thus, factors that encourage underreporting of pain or that reduce caregiver response may be especially important targets for researchers.

Finally, many Native patients use culturally-based, “traditional” treatments for pain management. Barriers involving access and communication with conventional providers may be so overwhelming that these alternatives seem especially appropriate. Nevertheless, the use of traditional medicine need not conflict with conventional treatments,4 and blended models of clinical practice that include both approaches have already proven successful.53, 67 Conventional and traditional pain treatment modalities can complement each other and ideally could become a standard of practice in healthcare settings that serve AI/ANs and Aboriginal Canadians.

Notable shortcomings in the literature on pain in these populations limit us to modest conclusions. Almost all of the articles we identified focused on small samples drawn from specific tribal groups, whereas the enormous linguistic and sociocultural variations among the indigenous populations of North America preclude generalizations from such data. Nevertheless, the common themes that we have articulated are consistent with previous studies on related issues in other minority populations, and therefore offer important guidance for future research.

Conclusions

Opportunities to study pain and painful conditions among AI/ANs and Aboriginal Canadians are immense. Future research efforts can be directed to investigating the prevalence of pain and comorbid conditions, especially mental health and substance abuse disorders; developing conceptual frameworks for pain among various cultural groups, including culturally-variant responses to pain; and evaluating relationships between healthcare providers and patients, focusing on communication and trust.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [U01 CA114642 to DB]; the National Center for Research Resources [1KL2-RR02-5015 to Mary Disis]; and the Department of Health and Human Services [1T32GM086270-01 to Debra Schwinn].

Footnotes

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest of any kind.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 2009;10:1187–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Valero V, Richman SP, Russell C, Hurley J, DeLeon C, Washington P, Palos G, Payne R, Cleeland CS. Minority cancer patients and their providers: pain management attitudes and practice. Cancer. 2000;88:1929–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KO, Richman SP, Hurley J, Palos G, Valero V, Mendoza TR, Gning I, Cleeland CS. Cancer pain management among underserved minority outpatients: perceived needs and barriers to optimal control. Cancer. 2002;94:2295–2304. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avery C. Native American medicine: traditional healing. Jama. 1991;265:2271–2273. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.17.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkwell D. Cancer pain: voices of the Ojibway people. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnabe C, Elias B, Bartlett J, Roos L, Peschken C. Arthritis in Aboriginal Manitobans: evidence for a high burden of disease. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1145–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the American Indian and Alaska Native population: United States, 1999-2003. Advance Data. 2005;356:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartz R. Beyond the biopsychosocial model: new approaches to doctor-patient interactions. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:601–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, Landi F, Gatsonis C, Dunlop R, Lipsitz L, Steel K, Mor V. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. Jama. 1998;279:877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry M, Reynoso C, Braceras J, Edley C, Kirsanow P, Meeks E. Broken promises: evaluating the Native American health care system. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Office of the General Counsel; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchwald D, Beals J, Manson SM. Use of traditional health practices among Native Americans in a primary care setting. Med Care. 2000;38:1191–1199. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchwald D, Goldberg J, Noonan C, Beals J, Manson S. Relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and pain in two American Indian tribes. Pain Med. 2005;6:72–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burhansstipanov L. Community-driven Native American cancer survivors' quality of life research priorities. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(Suppl 1):7–11. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler RN, Ballenger J, Glassman A, Stokes P, Zajecka J. Prevalence and consequences of depression in the elderly. Geriatrics. 1993;48(Suppl 2):2–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell CM, France CR, Robinson ME, Logan HL, Geffken GR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in the nociceptive flexion reflex (NFR) Pain. 2008;134:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Western bioethics on the Navajo reservation. Benefit or harm? Jama. 1995;274:826–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Bridging cultural differences in medical practice. The case of discussing negative information with Navajo patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:92–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.03399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities Health disparities defined. [November 2, 2010]; Available at http://crchd.cancer.gov/disparities/defined.html.

- 20.Cherry DK, Hing E, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury PP, Balluz L, Strine TW. Health-related quality of life among minority populations in the United States, BRFSS 2001-2002. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, Loehrer P, Pandya KJ. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):813–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen RA, Martinez ME. Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2008. National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cueva M, Lanier A, Dignan M, Kuhnley R, Jenkins C. Cancer education for Community Health Aides/Practitioners (CHA/Ps) in Alaska assessing comfort with cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20:85–88. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2002_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI. Back pain prevalence and visit rates: estimates from U.S. national surveys, 2002. Spine. 2006;31:2724–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000244618.06877.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon M, Mather DT, Shelton BL, Roubideaux Y. Economic and organizational changes in Indian health care systems. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, editors. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. American Public Health Association; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 89–121. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain. 2001;94:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elliott BA, Johnson KM, Eliott TE, Day JJ. Enhancing cancer pain control among American Indians (ECPCAI): a study of the Ojibwe of Minnesota. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:28–33. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferucci ED, Templin DW, Lanier AP. Rheumatoid arthritis in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferucci ED, Schumacher MC, Lanier AP, Murtaugh MA, Edwards S, Helzer LJ, Tom-Orme L, Slattery ML. Arthritis prevalence and associations in American Indian and Alaska Native people. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1128–1136. doi: 10.1002/art.23914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garroutte EM, Kunovich RM, Buchwald D, Goldberg J. Medical communication with American Indian older adults: Implications for models of racial/ethnic health disparities. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association; August 14, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garroutte EM, Kunovich RM, Buchwald D, Goldberg J. Medical communication in older American Indians: Variations by ethnic identity. J Appl Gerontol. 2006;25(Suppl 1):27S–43S. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garroutte EM, Westcott KD. “The Stories Are Very Powerful.” A Native American Perspective on Health, Illness and Narrative. In: Crawford S, editor. Religion and Healing in Native America. Praeger Press; Westport: 2008. pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaston-Johansson F, Albert M, Fagan E, Zimmerman L. Similarities in pain descriptions of four different ethnic-culture groups. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1990;5:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(05)80022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kalauokalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenwald HP. Interethnic differences in pain perception. Pain. 1991;44:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90130-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA. Trends in disability duration and cost of workers' compensation low back pain claims (1988-1996) J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:1110–1119. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199812000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Ruan WJ, Saha TD, Smith SM, Goldstein RB, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1062–1073. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huttlinger K, Krefting L, Drevdahl D, Tree P, Baca E, Benally A. “Doing battle”: a metaphorical analysis of diabetes mellitus among Navajo people. Am J Occup Ther. 1992;46:706–712. doi: 10.5014/ajot.46.8.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Mercer MB, Siminoff LA, Kwoh CK. Older patients' perceptions of quality of chronic knee or hip pain: differences by ethnicity and relationship to clinical variables. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:M472–477. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim C, Kwok YS. Navajo use of native healers. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2245–2249. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer BJ, Harker JO, Wong AL. Arthritis beliefs and self-care in an urban American Indian population. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:588–594. doi: 10.1002/art.10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer BJ, Harker JO, Wong AL. Descriptions of joint pain by American Indians: comparison of inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:149–154. doi: 10.1002/art.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lang GC. “Making sense” about diabetes: Dakota narratives of illness. Med Anthropol. 1989;11:305–327. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1989.9966000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leake J, Jozzy S, Uswak G. Severe dental caries, impacts and determinants among children 2-6 years of age in Inuvik Region, Northwest Territories, Canada. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manson SM. Culture and DSM-IV: implications for the diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders. In: Mezzich J, Kleinman A, Fabrega H, Parron D, editors. Culture and psychiatric diagnosis: a DSM-IV perspective. American Psychiatric Association Press; Washington, D.C.: 1996. pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mauldin J, Cameron HD, Jeanotte D, Solomon G, Jarvis JN. Chronic arthritis in children and adolescents in two Indian Health Service user populations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Max MB. How to move pain and symptom research from the margin to the mainstream. J Pain. 2003;4:355–360. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00719-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Classification of Chronic Pain. 2nd. IASP Press; Seattle: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miner J, Biros MH, Trainor A, Hubbard D, Beltram M. Patient and physician perceptions as risk factors for oligoanalgesia: a prospective observational study of the relief of pain in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:140–146. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore R, Brodsgard I. Cross-cultural investigations of pain. In: Crombie IK, Croft PR, Linton SJ, LeResche L, Von Korff M, editors. Epidemiology of Pain. IASP Press; Seattle: 1999. pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Center for Health Statistics . With Chartbook. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville: 2009. Health, United States, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nebelkopf E, King J. A holistic system of care for Native Americans in an urban environment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:43–52. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neff DF, Kinion ES, Cardina C. Nurse managed center: access to primary health care for urban Native Americans. J Community Health Nurs. 2007;24:19–30. doi: 10.1080/07370010709336583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelusi J, Krebs LU. Understanding cancer - understanding the stories of life and living. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(Suppl 1):12–16. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quandt SA, Chen H, Bell RA, Anderson AM, Savoca MR, Kohrman T, Gilbert GH, Arcury TA. Disparities in oral health status between older adults in a multiethnic rural community: the Rural Nutrition and Oral Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1369–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007;129:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rhee H. Prevalence and predictors of headaches in US adolescents. Headache. 2000;40:528–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rhee H. Racial/ethnic differences in adolescents' physical symptoms. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stephenson N, Dalton JA, Carlson J, Youngblood R, Bailey D. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer pain management. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2009;20:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. Jama. 2003;290:2443–2454. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strickland CJ. The importance of qualitative research in addressing cultural relevance: experiences from research with Pacific Northwest Indian women. Health Care Women Int. 1999;20:517–525. doi: 10.1080/073993399245601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Struthers R, Savik K, Hodge FS. American Indian women and cardiovascular disease: response behaviors to chest pain. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:158–163. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.U.S. Census Bureau . The American Indian and Alaska Native population 2000: Census 2000 Brief. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65.U.S. Census Bureau . Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2010. 129th. U.S. Bureau of the Census; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 66.U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Home Page. [April 27, 2010]; Available at http://www.doi.gov/bureaus/bia.cfm.

- 67.Wheatley MA. Developing an integrated traditional/clinical health system in the Yukon. Arctic Med Res (Suppl) 1991:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Woolfson P, Hood V, Secker-Walker R, Macauley AC. Mohawk English in the medical interview. Med Anthropol Q. 1995;9:503–509. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.4.02a00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zuckerman S, Haley J, Roubideaux Y, Lillie-Blanton M. Health service access, use, and insurance coverage among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Whites: What role does the Indian Health Service play? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:53–59. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]