Abstract

Despite findings that opioid detoxification serves little more than a palliative function, few patients who enter detoxification subsequently transition to long-term treatment. The current study evaluated intensive role induction (IRI), a strategy adapted from a single-session intervention previously shown to facilitate engagement of substance-dependent patients in drug-free treatment. IRI was delivered either alone or combined with case management (IRI+CM) to determine the capacity of each condition to enhance transition and engagement in long-term treatment of detoxification patients. Study participants were 240 individuals admitted to a 30-day buprenorphine detoxification delivered at a publicly-funded outpatient drug treatment clinic. Following clinic intake, participants were randomly assigned to IRI, IRI+CM, or standard clinic treatment (ST). Outcomes were assessed in terms of adherence and satisfaction with the detoxification program, detoxification completion, and transition and retention in treatment following detoxification. Participants who received IRI and IRI+CM attended more counseling sessions during detoxification than those who received ST (both p’s < .001). IRI, but not IRI+CM participants, were more likely to complete detoxification (p = .017), rated their counselors more favorably (p = .01), and were retained in long-term treatment for more days following detoxification (p = .005), than ST participants. The current study demonstrates that an easily administered psychosocial intervention can be effective for enhancing patient involvement in detoxification and for enabling their engagement in long-term treatment following detoxification.

Keywords: Opioid Addiction, Detoxification, Treatment Engagement

1. INTRODUCTION

As early as 1990, an Institute of Medicine (IOM - Gerstein and Harwood, 1990) report on drug addictions treatment indicated that “Detoxification is seldom effective in itself as a modality for bringing about recovery from dependence, although it can be used as a gateway to other treatment modalities… Clinicians generally advocate that, because of the narrow and short-term focus and very poor outcomes in terms of relapse to drug dependence, detoxification not be considered a modality of treatment …” (p. 16). Regardless of that recommendation, detoxification alone continues to be chosen by a substantial number of opioid-dependent individuals who may not wish to commit to long term opioid agonist maintenance therapy or residential treatment (Mark et al., 2002; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2009; Schwartz et al., 2008). However, one function that detoxification might serve in addition to its palliative function would be to facilitate the preparation and transition of patients into long-term treatment. Yet, research has shown that detoxification is largely ineffective at this function as well (Amato et al., 2004; Gossop et al., 1987). Indeed, more than a third of patients fail to complete methadone detoxification (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2008), and a recent multi-site trial found buprenorphine detoxification patients to fare as poorly with 44% of those receiving a 1 week taper and 30% of those receiving a 28 day taper opiate abstinent at the end of detoxification (Ling et al., 2009). Moreover, only 15–25% of detoxification patients were found to enter longer-term treatment (Chutuape et al., 2001; Lash, 1998; Mark et al., 2002; McCusker et al., 1995).

Recognition of the failure of detoxification by itself to encourage involvement in treatment has led to the development and testing of several initiatives to engage the detoxification patient in continuing treatment. In these studies, patient involvement in long-term treatment following inpatient detoxification was found to be enhanced through the use of a therapeutic community program (Collins et al., 2007), and intensive programming involving aftercare planning, group therapy, and goal-setting sessions among other services offered (Carroll et al., 2009). Case management initiatives have also been shown to facilitate patient engagement in long-term treatment (Booth et al., 1996; Mejta et al., 1997) as well as transition to treatment following detoxification (Shwartz et al., 1997).

Role induction strategies, with their emphasis on helping individuals examine and adopt the role of drug abuse patient, have been found effective in increasing treatment entry and engagement (Stark and Kane, 1985; Verinis, 1993; 1996). In our earlier research, patients entering a drug-free outpatient treatment clinic were randomly assigned to receive either role induction, a single 45-minute manual-guided treatment session that was delivered by the counselor with whom the patient would continue in treatment on the day of treatment entry, or to routine clinic treatment. Role Induction, compared to routine treatment, was found to increase the likelihood of attending an initial treatment session, was associated with longer time retained in treatment, and with more positive attitudes toward the treatment program (Katz et al., 2004; 2007).

Consistent with prior research demonstrating the efficacy of both role induction and case management for facilitating treatment entry and engagement among opioid-dependent patients following detoxification, the current study was designed to compare engagement in detoxification and transition to long-term treatment following detoxification among opioid-dependent patients who were randomly assigned to routine counseling, to role induction alone, and to role induction in combination with case management. The setting for the study was a 30-day buprenorphine detoxification program operating within an outpatient (non-methadone) treatment program. The primary outcomes of interest were detoxification engagement and transition to long-term treatment. Treatment engagement was assessed in terms of (a) adherence to individual counseling sessions by study Treatment Condition during the 30 day detoxification; and (b) completion of the detoxification regimen. Transition and engagement into longer-term treatment were assessed in terms of (a) attendance at one or more post-detoxification treatment sessions, and (b) the number of days retained in treatment post-detoxification. Secondary analyses explored the impact of study Treatment Condition, in terms of counselor rapport and treatment satisfaction. We hypothesized that role induction alone and combined with case management would result in greater outcomes on both primary and secondary measures compared to standard treatment.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

2.1.1 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Study participants were recruited from among individuals seeking admission to a 30-day buprenorphine detoxification at a publicly-funded outpatient drug treatment clinic in Baltimore City between May 2, 2005 and May 6, 2008. All treatment entrants who were 18 years or older, opiate-addicted, and had been admitted for buprenorphine detoxification were eligible for the study. Study exclusion criteria included: pregnancy, suicidal ideation, psychosis, cognitive impairment sufficient to interfere with the individual’s ability to provide informed consent, and refusal to provide information necessary to locate the individual for follow-up. The study was reviewed and approved by the Friends Research Institute and the University of Maryland School of Medicine IRB.

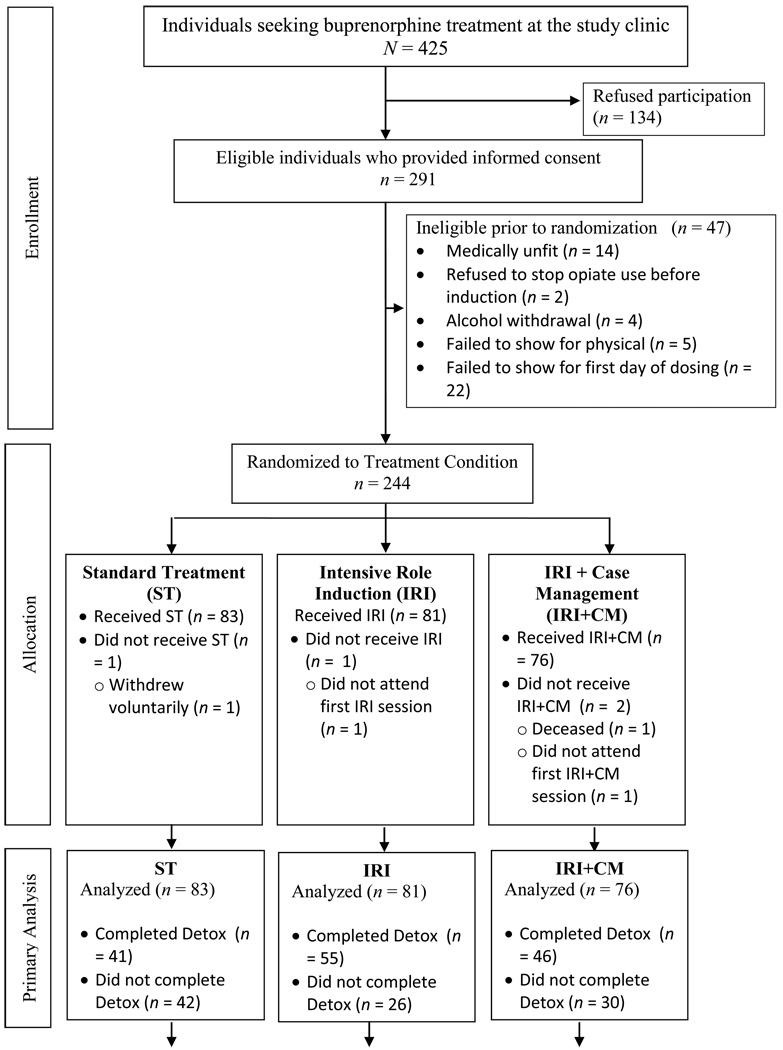

As illustrated in Figure 1, 425 individuals sought buprenorphine treatment at the study clinic during the period of study recruitment. Of those individuals, 291 elected buprenorphine detoxification and provided written informed consent while the vast majority of the remaining patients elected buprenorphine maintenance and were therefore not available to this study. Following informed consent but prior to randomization, 47 participants were excluded for any of several reasons (see Figure 1). Two additional participants were found ineligible to participate, one died during the early stages of the study, and a third withdrew consent to participate, leaving an intent-to-treat sample of 240 participants who provided written informed consent to participate and were medically qualified to take buprenorphine.

Fig. 1.

Pipeline flowchart of participants from study entry through 1-month follow-up.

2.2 Procedures

Potential patients contacted the treatment clinic by telephone and completed a brief interview schedule; those who qualified for buprenorphine treatment were scheduled for an orientation session within two weeks. At their first visit individuals received the clinic orientation from an available counselor. The orientation consisted of a 15-minute discussion with program entrants about the nature and course of treatment, the specific services available at the clinic, the importance of participation in treatment to overcome drug abuse, and expectations the clinic had for the patient with regard to attendance. The orientation format was didactic although it did permit questioning by individuals. Following completion of the clinic orientation, patients were greeted by the clinic director who informed them of their treatment options (either buprenorphine maintenance or detoxification).

Those individuals electing detoxification were invited by a research assistant to participate in the study and patients who expressed interest in the study had the consent form read aloud to them. Upon providing written informed consent, participants completed both clinic and study baseline assessments, were randomly assigned to one of the three treatment conditions (i.e., standard clinic treatment [ST], intensive role induction [IRI] only, or intensive role induction combined with case management [IRI+CM]) and were scheduled to meet with the clinic physician the next day for a medical examination. Following the medical examination, participants who were medically qualified to take buprenorphine were administered their first dose of buprenorphine/naloxone.

After receiving medication, participants assigned to ST were scheduled for an individual session with their treatment counselor later in the week (and provided a business card with the day/time of that appointment) whereas those assigned to IRI only or to IRI+CM met with their treatment counselor for the initial IRI session. All research participants completed study questionnaires for which they were paid $20 and then excused. Participant attendance at treatment was monitored for the length of the study.

2.2.1 Detoxification protocol

Participants were inducted onto buprenorphine over a period of 4 days. On the first day, participants received 4 mg of suboxone™ (a 4:1 ratio of buprenorphine to naloxone). The participants’ dose was increased by 4 mg of buprenorphine/naloxone per day until a “maintenance” dose (i.e., the patient reported no withdrawal symptoms) or the maximum dose (i.e., 16 mg) was achieved. Participants were maintained on the “maintenance” dose for 19 days (M maintenance dose = 15.2 mg of buprenorphine/naloxone) and then tapered off the medication over a period of 7 days. During the first two weeks of detoxification, participants received their medication dose daily at the clinic with take-home doses for the weekend. During the remainder of the 30-day detoxification period participants were given one week’s worth of medication to take at home.

2.3 Treatment Conditions

2.3.1 Standard Treatment (ST)

ST consisted of the individual counseling services normally provided in association with the detoxification at the study treatment clinic. The five individual counseling sessions in the ST condition following orientation consisted of once weekly individual counseling services which focused on discussion of the disease model of addiction and problem-solving issues and concerns raised by patients during each session.

2.3.2 Intensive Role Induction (IRI)

IRI was based on the single-session strategy found effective in our earlier work for engaging patients entering drug-free outpatient treatment (Katz et al., 2004; 2007). In general, IRI focused on psychoeducation about detoxification, addressing misperceptions about detoxification and treatment, addressing concerns and barriers to continued involvement in treatment, and emphasized the value of continuing in treatment beyond detoxification to solidify treatment gains. In contrast to other early engagement interventions [such as motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick, 2002)], IRI clinicians emphasize that treatment and recovery involves a partnership between the patient and counselor and focus on practical strategies for overcoming barriers to engagement (e.g., scheduling counseling sessions at convenient times for patients) rather than on mobilizing internal motivation for change. In the current study, IRI consisted of five, once-weekly, individual counseling sessions over the course of the 30-day detoxification with the counselor with whom the participant would continue in treatment. The initial session was kept purposefully brief as it was scheduled to occur on the day the participant received his/her first dose of buprenorphine/naloxone. This session focused on educating study participants about buprenorphine and how it would help them to detoxify from heroin. Participants were informed about over the counter medications they could use to manage any residual withdrawal symptoms or medication side effects. They were also encouraged to talk to the clinic nurse or physician if they had any concerns regarding the medication and its effects.

The next two sessions (sessions 2 and 3) focused on the importance of attending all scheduled sessions during detoxification and of complying with the medication. The counselor addressed any concerns the participant had about taking medication, answered any further questions the participant had about buprenorphine or the purpose of detoxification in the process of recovery, and problem-solved with the participant to ensure compliance with the medication regimen. These sessions also introduced the idea that detoxification is a first step in the process of recovery as well as the benefits of continuing in treatment for enhancing the chances of recovery.

The final two sessions (sessions 4 and 5) further emphasized detoxification as a first step in the process of recovery as well as the need to continue in treatment in order to achieve and sustain abstinence. Counselors elicited and addressed any concerns the participant had about continuing in treatment as well as problem-solved any barriers to continuing in treatment that were identified. The counselor also emphasized that s/he would continue to work as a partner in the patient’s recovery even after the detoxification was completed. All IRI sessions were guided by a treatment manual developed specifically for the current study.

2.3.3 IRI plus Case Management (IRI+CM)

Participants assigned to IRI+CM received IRI, as described above, as well as assistance from the counselor in accessing community resources that would support their efforts at recovery. While IRI focused on addressing practical barriers to engagement, as is also done in IRI+CM, the emphasis in IRI alone is on services available within the drug treatment clinic as well as changes in the way that patients view treatment and barriers to engagement. Conversely, IRI+CM focused on helping patients to obtain concrete services available through outside agencies. Issues appropriate for Case Management included those concerns involving the individual, and/or his/her immediate family members, that could be seen as critical to the well-being of the individual or family members in their own right and/or as having the potential to impede treatment engagement (e.g., the patient’s need to obtain temporary housing). Counselors provided active case referral which included advocacy in accessing needed services. During each session, counselors reviewed the results of Case Management efforts undertaken, determined any additional steps to be pursued in relation to the participant’s needs, and continued to assess the functioning of the participant and his/her family in relation to community services available.

A model for allowing typical counseling staff to provide Case Management services specific to the Baltimore community is available in the manual developed for use in association with an aftercare program organized and evaluated by study investigators (Brown et al., 1999). That program was found to reduce drug and alcohol use and criminal activity (Brown et al., 2001; 2004). Counselors used Resource Directories which described services available in the Baltimore area by type of agency, and included address, phone number, hours of operation, nature of patients served, exclusionary criteria, contact person, etc.

2.3.4 Treatment Elements Common to All Three Treatment Conditions

At intake, participants were assigned a counselor, consistent with their random assignment (i.e., ST, IRI, IRI+CM), and remained with that counselor for the duration of their treatment (i.e., both detoxification and post-detoxification counseling). All three interventions consisted of once weekly individual sessions for the first five weeks of treatment. All participants, regardless of treatment condition, were eligible to receive intensive outpatient group therapy for the five weeks of detoxification. Following detoxification, all participants were eligible to receive at least once weekly individual counseling and once weekly group counseling. Counseling could be increased depending on staff judgment of patient needs. Although treatment was expected to last 6 months, participants could remain in treatment indefinitely depending on their needs.

2.3.5 Treatment Providers

Certified addictions counselors, ranging in education from associates to masters degree level, delivered one of the three interventions over the course of the study. Seven of the counselors were male and all were African American. At any given time, two counselors were assigned to deliver each of the three interventions. Within each condition, one counselor was assigned to the study full-time while the other was assigned to the study on a part-time basis; however, all clinicians maintained the equivalent of a full-time clinic caseload which included both study and non-study patients. To prevent contamination of the three treatment conditions, each counselor was assigned to deliver only one of the three interventions and received training, consistent with their assignment. Because of counselor turnover throughout the study, the number of counselors assigned to each condition and the number of participants that each clinician treated differed across conditions. Specifically, 7 counselors delivered the IRI intervention and the number of IRI patients treated by these counselors ranged from 1 to 26. Four counselors delivered the IRI+CM intervention over the course of the study and the number of IRI+CM patients treated by these counselors ranged from 1 to 47. Finally, four counselors delivered the ST intervention over the course of the study; the number of ST patients treated by these counselors ranged from 9 to 47.

2.4 Monitoring Fidelity to the Treatment Conditions

A number of procedures were used to ensure that counselors adhered to their respective treatment protocols and that the treatment conditions were clearly distinguishable from one another. First, as noted above, the IRI+CM and IRI treatment conditions were each guided by their own detailed treatment manuals (copies of the manuals are available upon request from the first author). Counselors assigned to these conditions were trained to deliver the intervention by one of the investigators over a period of two days. Second, a fidelity measure was developed to assess counselor behaviors that were unique and essential to the specific treatment condition (e.g., for IRI: counselor stated that she or he would be a partner in the patient’s recovery; for IRI+CM: counselor assisted the patient in obtaining needed social services) as well as behaviors that were inappropriate to each treatment condition. Finally, counselors audio-recorded all of their treatment sessions; recordings were collected daily for review.

The fidelity measure used in this study included items that described concrete counselor behaviors that were either: (1) Unique and Essential to IRI, (2) Unique and Essential to CM, or (2) Essential or Allowed but not Unique to IRI or CM. Specific measures were developed for each of the 5 individual sessions that were planned during the 30-day detoxification. The number of items that were considered Unique and Essential to IRI ranged from 4 in the 5th session to 11 in the second session. Those items considered Unique and Essential to CM ranged from 2 items in the initial session to 8 items in the final three sessions. The number of Allowed but not Unique elements ranged from 7 items in the last three sessions to 9 items in the first two sessions. Unique and Essential items to IRI included specific statements by the counselor indicating his/her view that detoxification was only the first step in the process of recovery, statements by the counselor addressing misperceptions the patient had about buprenorphine and/or treatment, etc. Items that were Unique and Essential to Case Management included questions raised by the counselor about the patient or patient/family problems that might interfere with treatment participation; an offer by the counselor to contact social services or other community agencies on the patient’s behalf. The following criteria were used to determine adherence to the three conditions across the five treatment sessions:

Adherence to IRI. To be adherent to IRI, counselors needed to have exhibited at least 75% of the Unique and Essential IRI behaviors, at least 50% of the Allowed but not Unique items, and none of the CM items.

Adherence to IRI+CM. To be adherent to IRI+CM, counselors needed to have exhibited at least 75% of the Unique and Essential IRI behaviors, at least 50% of the Allowed but not Unique items, and at least 75% of the Unique and Essential CM behaviors (or 100% of the CM behaviors for the first sessions which only included 2 CM behaviors).

Adherence to ST. To be considered adherent to the ST condition, counselors had to have included no more than 20% of the elements considered unique and essential to IRI and CM. There was no limit on the number of Allowed but not Unique items that they could have exhibited.

Using the fidelity measure, tapes from each of the five relevant treatment sessions were rated by two judges (a co-I and the project manager), both of whom were independent of clinical programming, and had detailed knowledge of the three treatment protocols as well as experience with the development and use of the fidelity measure. Sessions from every counselor were included in the assessment of adherence to the study protocol, and each rating of fidelity involved the judge's review of the entire session being evaluated. Non-adherence to the treatment protocol was noted and addressed through supervision and re-training. In accord with the criteria enumerated above for determining fidelity, adherence to the protocols overall was found to be 92.5%. Adherence rates for the three treatment conditions are as follows: 100% of ST sessions, 90.2% of IRI sessions, and 87.3% of IRI+CM sessions were found to show fidelity to the intervention protocol, indicating high levels of adherence to each study condition.

2.5 Measures

During-detoxification outcomes were assessed in terms of: (a) program adherence (i.e., number of individual counseling sessions attended) and (b) detoxification completion (detoxification completion was defined as having missed no more than two buprenorphine doses during the 30-day period). Transition to post-detoxification treatment was assessed in terms of (a) attendance at one or more post-detoxification treatment sessions; and (b) number of days retained in treatment post-detoxification (i.e., from the first post-detoxification day to the last face-to-face encounter with the counselor).

2.5.1 Individual Counseling Session Attendance and Post-Detoxification Session Attendance

Counseling session attendance throughout treatment was assessed employing a rating form designed for use with this study. Counselors completed the form to indicate when an individual counseling session had been scheduled and whether or not the patient attended the scheduled session.

2.5.2 Treatment Retention

Retention in treatment post-detoxification was measured in terms of days of continuous involvement from the day after detoxification completion to the last face-to-face contact with the counselor. Consistent with routine clinic practice, patients were considered to have dropped out of treatment if a period of 30 days had elapsed with no face-to-face contact between the counselor and patient.

2.5.3 Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

The ASI (McLellan et al., 1992) assesses patient functioning in terms of drug and alcohol use, employment, legal, medical and psychiatric status, family functioning and social relations through use of a 45–60 minute face-to-face interview. The full ASI was administered at baseline and was used to derive participant demographic characteristics.

2.5.4 Client and Counselor Evaluation Forms

The IRI and IRI+CM treatment conditions were expected to have a positive impact on the participant’s view of the patient-counselor relationship and of drug abuse treatment. Two scales, derived from the Drug Abuse Treatment and AIDS Risk-Reduction (DATAR) project, were employed to measure aspects of the patient-counselor relationship and attitudes toward treatment (Simpson and Chatham, 1995). The 22-item Client Evaluation Form includes 10 items exploring regard for the counselor, labeled as “counselor respect”; and an additional 12 items exploring Satisfaction with Treatment Progress.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

χ2 goodness-of-fit tests for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance for continuous variables were conducted to ensure that baseline characteristics that might be related to treatment outcomes (e.g., gender; days of heroin use) were not different among treatment conditions. Univariate analysis of variance and hierarchical logistic regression analysis were conducted using simple contrasts, in which each experimental condition (i.e., IRI; IRI+CM) was compared to the reference category (i.e., ST), consistent with our stated hypotheses. Because we had two families of primary outcomes, each with two measures, we used Bonferroni’s inequality to adjust our alpha level to reduce the risk of Type I error. Thus, a p-value of .025 was used for determining statistical significance for all analyses (including the secondary outcomes). However, tendencies were reported at p values between .025 and .10 in the interest of highlighting issues that might be appropriate for future study.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Study participants (N = 240) averaged 43.1 years of age (SD =6.9), were predominantly never married (58.6%), African American (96.2%), and male (55.2%). They had completed an average of 11.6 (SD = 1.7) years of education and reported having been paid for working an average of 4.9 (SD = 8.4) days out of the 30 prior to treatment entry (71.3% reported not having worked for pay during that time period). All participants submitted urine specimens at baseline that were positive for opiates and 54.8% also tested positive for cocaine; they self-reported using opiates on 28.0 (SD = 5.3) days and cocaine on 9.4 (SD = 11.5) days during the 30 prior to treatment entry. A large minority (23.6%) reported using heroin by injection. Participants reported 2.2 (SD = 2.5) prior treatment episodes for drug abuse; of those treatment episodes, 2.1 (SD = 2.3) were for detoxification only. About one third of participants reported that they were on probation or parole at the time of treatment admission and 26.6% stated that the current treatment admission was prompted or suggested by the criminal justice system.

3.1.1 Analysis of Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 displays the baseline demographic characteristics of the study sample. Analyses indicated no significant differences between the three treatment groups on these baseline characteristics discussed above.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics

| Total Sample |

Standard Treatment |

Intensive Role Induction |

IRI + Case Management |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=240 | n=83 | n=81 | n=76 | ||

| M (SD) | |||||

| Age | 43.1 (6.9) | 43.6 (6.8) | 42.1 (5.8) | 43.7 (8.0) | .27 |

| Years of Education | 11.6 (1.7) | 11.4 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.7) | 11.6 (1.8) | .13 |

| Days of Opiate Use, past 30 | 28.0 (5.3) | 27.8 (5.4) | 28.3 (5.0) | 28.1 (5.5) | .85 |

| Days of Cocaine Use, past 30 | 9.4 (11.5) | 9.9 (11.7) | 7.7 (10.8) | 10.7 (12.0) | .24 |

| Number of Arrests, Lifetime | 6.7 (6.7) | 7.6 (7.1) | 6.0 (6.9) | 6.6 (6.0) | .28 |

| Number of prior treatment episodes | 2.2 (2.5) | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.2 (1.9) | 2.5 (3.3) | .39 |

| Number of detoxification-only episodes | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.1 (3.3) | .82 |

| f (%) | |||||

| Male | 54.8 | 54.2 | 56.8 | 53.9 | .88 |

| African American | 96.2 | 95.2 | 97.5 | 96.0 | .54 |

| Paid for working on no days, past 30 | 70.1 | 72.3 | 71.6 | 67.1 | .74 |

| Never married | 58.9 | 63.9 | 53.2 | 57.9 | .49 |

| Opiate-positive | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | NA |

| Cocaine-positive | 54.4 | 47.0 | 58.0 | 59.2 | .20 |

| Injecting opiates | 23.6 | 31.3 | 19.0 | 20.0 | .27 |

| On parole or probation | 35.7 | 37.3 | 35.8 | 34.2 | .94 |

| Treatment was suggested by the criminal justice system | 26.1 | 28.9 | 21.0 | 28.9 | .46 |

3.2 Primary Outcome Measures

3.2.1 Detoxification Engagement

A univariate analysis of variance on the number of individual counseling sessions attended during the detoxification period was conducted using simple contrasts and ST as the reference category. These contrasts indicated that both IRI (M = 3.4, SE = .16; p < .001) and IRI+CM (M = 3.2, SE = .17; p < .001) participants attended significantly more individual counseling sessions during detoxification than ST (M = 2.0, SE = .16) participants.

A logistic regression analysis with simple contrasts using ST as the reference category revealed that IRI (OR = 2.2; 95%CI: 1.1–4.1; p = .017), but not IRI+CM (OR = 1.6; 95%CI: 0.8– 2.9; p = .16) participants were more likely than ST participants to complete the detoxification. Whereas 67.9% of IRI participants completed detoxification, only 49.4% of ST participants did so.

3.2.2 Transition and Engagement into Longer-Term Treatment

Results of a logistic regression analysis using simple contrasts with ST as the reference category revealed a tendency for IRI participants (OR = 1.7; 95%CI: .92–3.2; p = .09) to be more likely than ST participants to attend at least one post-detoxification treatment session. There was no difference in the likelihood that IRI+CM and ST participants would attend a post-detoxification session (OR = 1.3; 95%CI: .69–2.4; p = .42).

A one-way univariate analysis of variance with simple contrasts supported our hypothesis regarding retention for IRI but not for IRI+CM participants. Specifically, results revealed that IRI (M = 34.9; SE = 4.7; p = .005) but not IRI+CM (M = 21.6; SE = 4.8; p = .42) participants were retained in treatment for more days following detoxification than ST participants (M = 16.1; SE = 4.6).

3.3 Secondary Outcome Measures

3.3.1 Counselor rapport and treatment satisfaction

A univariate analysis of variance with simple contrasts comparing IRI and IRI+CM to ST, respectively, indicated that IRI (M = 6.1; SE = .16), but not IRI+CM (M = 5.7; SE = .16), participants rated their counselor more positively at the 1-month follow-up period than ST participants (M = 5.5; SE = .16), p = .01. Neither IRI nor IRI+CM significantly differed from ST in terms of treatment satisfaction at 1-month follow-up (both ps > .10).

3.4 Analyses with Covariates

Close examination of Table 1 suggests that, while non-significant, some differences in baseline between the three groups might be seen to favor IRI over ST or IRI+CM. Therefore, we re-ran the analyses including the following variables as covariates: years of education; days of cocaine use, past 30; number of arrests, lifetime; number of prior treatment episodes; and whether participants attended treatment at the urging or suggestion of the criminal justice system.

All results of primary and secondary analyses remained statistically significant (p < .025) with two exceptions. The tendency for IRI, as compared to ST, participants to be more likely to attend a post-detoxification session was no longer significant (p = .15). The finding that IRI, as compared to ST, were more likely to complete detoxification was reduced to a tendency (p = .037).

4. Discussion

The current study was designed to examine the degree to which Intensive Role Induction (IRI) administered either alone or in combination with Case Management (IRI+CM) would produce greater adherence to the detoxification regimen, detoxification completion, and initiation of outpatient treatment compared to standard clinic treatment (ST). Overall, IRI participants enjoyed the most positive outcomes relative to ST participants on measures of engagement during and following detoxification. Specifically, IRI participants, compared to ST participants, on average attended more counseling sessions during detoxification, were more likely to complete detoxification, rated their counselors more favorably, and remained in treatment for a longer period following detoxification. IRI+CM was not found to be similarly effective. Specifically, the only significant effect for IRI+CM, compared to ST participants, was for greater counseling session attendance during detoxification.

Study findings are consistent with our earlier work (Katz et al., 2004; 2007) demonstrating the benefit of role induction for facilitating patient engagement in substance abuse treatment. Results of the current study further suggest that participants who received IRI in combination with a month-long detoxification program were more likely to complete the detoxification regimen, with a more positive view of the counselors with whom they were working, and a greater willingness to remain in long-term treatment. Thus, IRI may help to alter the role of detoxification from serving only a palliative function to that of preparing patients to take greater advantage of long-term treatment services.

While IRI alone was seen to be effective for improving treatment engagement, IRI combined with CM was found to be no more effective than ST treatment in terms of the outcome measures assessed. This finding conflicts with our expectations and prior research demonstrating the utility of case management in fostering treatment entry and engagement (Booth et al., 1996; Mejta et al., 1997; Robles et al., 2004; Shwartz et al., 1997; Strathdee et al., 2006). One potential explanation for this result is the difficulty counselors may have had in providing two separate interventions, with somewhat different goals, within the same timeframe during which they would ordinarily implement only a single intervention (either IRI or CM). The fidelity measures suggested that IRI+CM clinicians administered that intervention with the same degree of fidelity as counselors in the other two conditions. What that measure does not assess is the quality with which the intervention was delivered. Thus, the task of implementing two different interventions within the same one-hour counseling session may have posed a formidable challenge to clinicians, thereby reducing the quality of treatment and undermining the effectiveness of both interventions. At the same time the counselor providing CM is largely at the mercy of the ability and willingness of community agencies, over which he or she has no control, to make resources available – resources that can be seen as being in increasingly short supply. That can lead to the patient, and the counselor, having expectations about the level of services to be garnered that cannot be fulfilled, resulting in frustration for them both and negative consequences for their relationship and the capacity of CM to be an aid to treatment. Support for this explanation is suggested by the finding that IRI but not IRI+CM participants rated their counselor more favorably.

Limitations of the current study include the lack of a case management alone condition which would have permitted an assessment of the effectiveness of CM by itself, in comparison to ST, IRI, and IRI+CM, for facilitating treatment entry, engagement and outcomes. A second limitation is the relatively low study acceptance rate; while 425 individuals sought treatment during the period of study recruitment, only 291, or 68%, provided informed consent to participate. This is likely due to the fact that Baltimore City instituted its Buprenorphine Initiative (BBI) approximately 6 months after study recruitment began. The BBI made buprenorphine maintenance readily available in Baltimore City treatment clinics (including the study clinic); thus, study participants were those individuals who elected to enroll in buprenorphine detoxification rather than maintenance. To some extent, individuals electing detoxification over maintenance may represent an even more difficult to engage population; one may presume that this population was purposefully electing the treatment option requiring the least commitment. If this is the case, it further suggests the value of role induction strategies for enhancing early treatment engagement. Finally, unlike participants in the IRI and IRI+CM conditions, ST participants were not required to attend a counseling session on the first day of detoxification; rather they were provided with an appointment with their counselor that was scheduled to occur sometime during the first week of treatment as was routinely done with entering patients. In fact, while 100% of IRI and IRI+CM participants attended the first treatment session, only 34% of ST participants made it to an individual counseling session during the first week of treatment. Thus, it is plausible that simply scheduling early contact with the counselor, rather than the actual content of that contact, influenced rates of engagement and session attendance as has been suggested in earlier studies (Bell et al., 1994; Rosenberg et al., 1972). This explanation can be seen as called into question by the finding that IRI, but not IRI+CM, was associated with improvements in all measures of engagement. Nonetheless, future research should examine more directly the extent to which engagement measures are impacted by the timing or content of the IRI sessions.

Despite these limitations, the current study demonstrates that an easily administered psychosocial intervention can be effective for enhancing patient involvement in detoxification as well as their transition to long-term treatment following detoxification. Intensive Role Induction, a brief (i.e., 5-session) intervention was found to be easily adopted by existing counselor staff and readily integrated into routine treatment. Thus, IRI is appropriate for use in typical community-based drug treatment programs and appears capable of increasing patient engagement in those settings.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the administrative, counseling, and support staff of the University Of Maryland Harambee Treatment Center for their assistance in recruiting study participants and in implementing the study treatment protocols.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant # RO1 DA011402. Reckitt Benckiser provided support for this work in the form of study medication. Neither NIDA nor Reckitt Benckiser had a role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

The first author, Katz, in association with the second, third, and fourth authors, Brown, Schwartz, and O’Grady conceived of the study. The first author Katz, in collaboration with second author, Brown, developed the study treatment manuals and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. The third author, Schwartz, ensured that counselors adhered to their respective treatment protocols and provided comments on all drafts of the manuscript. The fourth author, O’Grady developed the analysis plan, assisted the first author, Katz, with the conduct of the statistical analyses, and provided comments on all drafts of the manuscript. The fifth author, King, oversaw the data collection, managed study databases, and prepared the data for analysis. The final author, Gandhi, assisted the first and fifth authors in overseeing the process of data collection and assisted with study IRB approval at the University Of Maryland School Of Maryland. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest are reported.

REFERENCES

- Amato L, Davoli M, Ferri M, Gowing L, Perucci CA. Effectiveness of interventions on opiate withdrawal treatment: an overview of systematic reviews. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J, Caplehorn JM, McNeil DR. The effect of intake procedures on performance in methadone maintenance. Addiction. 1994;89:463–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Crowley TJ, Zhang Y. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and effectiveness: out-of-treatment opiate injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, Farrell G, Voskuhl T. Aftercare to Reduce Risk and Relapse of HIV Infection. 1999 Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, O'Grady, Battjes RJ, Farrell E, Smith N, Nurco D. Effectiveness of a stand-alone aftercare program for drug-involved offenders. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2001;21:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BS, O’Grady KE, Battjes RJ, Katz EC. The Community Assessment Inventory - measuring community support for drug treatment and behavior change. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;27:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CP, Triplett PT, Mondimore FM. The Intensive Treatment Unit: a brief inpatient detoxification facility demonstrating good postdetoxification treatment entry. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;37:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape MA, Katz EC, Stitzer ML. Methods for enhancing transition of substance dependent patients from inpatient to outpatient treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins ED, Horton T, Reinke K, Amass L, Nunes EV. Using buprenorphine to facilitate entry into residential therapeutic community rehabilitation. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;32:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Bradley B, Phillips GT. An investigation of withdrawal symptoms shown by opiate addicts during and subsequent to a 21-day in-patient methadone detoxification procedure. Addict. Behav. 1987;12:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein DR, Harwood HJ. Treating Drug Problems. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Katz EC, Brown BS, Schwartz R, Weintraub E, Barksdale W, Robinson R. Role induction: a strategy for improving retention in outpatient drug-free treatment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:227–234. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz EC, Brown B, Schwartz R, King SD, Weintraub E, Barksdale W. Impact of role induction on long-term drug treatment outcomes. J. Addict. Dis. 2007;26:81–90. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n02_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SJ. Increasing participation in substance abuse aftercare treatment. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24:31–36. doi: 10.3109/00952999809001697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Hillhouse M, Domier C, Doraimani G, Hunter J, Thomas C, Jenkins J, Hasson A, Annon J, Saxon A, Selzer J, Boverman J, Bilangi R. Buprenorphine tapering schedule and illicit opioid use. Addiction. 2009;104:256–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Dilonardo JD, Chalk M, Coffey RM. Trends in inpatient detoxification services, 1992–1997. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2002;23:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker J, Bigelow C, Luippold R, Zorn M, Lewis BF. Outcomes of a 21-day drug detoxification program: retention, transfer to further treatment, and HIV risk reduction. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:1–16. doi: 10.3109/00952999509095225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejta CL, Bokos PJ, Mickenberg J, Maslar ME, Senay E. Improving substance abuse treatment access and retention using a Case Management approach. J. Drug Issues. 1997;27:329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2nd edition. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robles RR, Reyes JC, Colon HM, Sahai H, Marrero CA, Matos TD, Calderon JM, Shepard EW. Effects of combined counseling and case management to reduce HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic drug injectors in Puerto Rico: a randomized controlled study. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;27:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg CM, McKain N, Patch V. Engaging the narcotic addict in treatment. Drug Forum. 1972;1:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O'Grady KE, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Mitchell SG, Wilson ME, Agar MH, Brown BS. In-treatment vs. out-of-treatment opioid dependent adults: drug use and criminal history. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:17–28. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwartz M, Baker G, Mulvey K, Plough A. Improving publicly funded substance abuse treatment: the value of Case Management. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87:1659–1664. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Chathman LR. TCU/DATAR Forms Manual. Fort Worth, Texas: Institute of Behavioral Research; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stark MJ, Kane BJ. General and specific psychotherapy role induction with substance-abusing clients. Int. J. Addict. 1985;20:1135–1141. doi: 10.3109/10826088509056355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Ricketts EP, Huettner S, Cornelius L, Bishai D, Havens JR, Beilenson P, Rapp C, Lloyd JJ, Latkin CA. Facilitating entry into drug treatment among injection drug users referred from a needle exchange program: results from a community-based behavioral intervention trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2005. Rockville, MD: Discharges from Substance Abuse Treatment Services. 2008 DASIS Series: S-41, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08-4314.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS). Highlights - 2007. Rockville, MD: National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. 2009 DASIS Series: S-45, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 09-4360.

- Vernis J. Alcoholics' initial expectations of and attitudes toward treatment. Int. J. Addict. 1993;28:827–836. doi: 10.3109/10826089309039659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verinis J. The effect of an orientation-to-treatment group on the retention of alcoholics in outpatient treatment. Subst. Use Misuse. 1996;31:1423–1432. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]