Abstract

Background and aims

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is associated with a high mortality rate in the absence of liver transplantation. There is limited data on predictors of survival in ACLF in children. Therefore, we prospectively studied the predictors of outcome of ACLF in children.

Methods

A prospective evaluation of 31 children in the age group of 1–16 years who fulfilled the criteria for ACLF according to Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2008 consensus was done. All consecutive children were evaluated for etiology, diagnosis and severity of ACLF. For grading of organ dysfunction, the sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score was calculated. SOFA constitutes the parameters of respiration, coagulation, cardiovascular system, central nervous system, and renal and liver functions. We evaluated possible correlation between outcomes and different variables.

Results

Of the 31 children who fulfilled the criteria for ACLF, the common underlying chronic liver diseases (CLD) were autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in 41.9% and Wilson disease in 41.9% of the patients. Superinfection with hepatitis A virus (HAV) (41.9%) was the most common etiology of acute deterioration. To find the best predictor for outcome, linear regression analysis was performed. Multivariate analysis revealed that the SOFA score and the International Normalized Ratio (INR) were predictors of survival. Six (19.4%) patients died. Causes of death were multiorgan failure in four and liver failure in two patients.

Conclusion

The mortality in ACLF is 19.4% and the causes of death were multiorgan failure and liver failure. The SOFA score and INR were predictors of outcome of ACLF in children.

Keywords: Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Predictors of mortality, Sequential organ failure assessment

Introduction

Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is defined by the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of Liver (APASL, 2008) as an acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice and coagulopathy, complicated within 4 weeks by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease [1]. Acute-on-chronic hepatitis (AOCH) can cause irreversible hepatic failure, and is associated with a mortality rate of over 70% if liver transplantation is not available [2]. It is important to determine the prognosis in ACLF especially over the short-term, with respect to the use of temporary liver support or even transplantation in these patients. The prognosis of ACLF can be assessed by Child-Pugh score, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, APACHE-II or III and SOFA. There are limited data on the predictors of survival in children with ACLF. Therefore, we prospectively studied the predictors of outcome of ACLF in children.

Patients and methods

We prospectively evaluated 31 children diagnosed with ACLF by the APASL criteria [1] in the age group of 1–16 years, admitted to the Pediatric Gastroenterology Ward in the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, from December 2007 to May 2009. To evaluate the etiology, diagnosis and severity of ACLF, all consecutive patients were investigated with complete blood counts, liver function tests, prothrombin time index (PTI) or International Normalized Ratio (INR) and renal function tests. Serological markers for viral hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hepatitis E were performed by micro-ELISA technique. For the etiological diagnosis of Wilson disease, serum ceruloplasmin, slit lamp examination for Kayser-Fleischer rings, 24-h urinary copper and serum copper were performed. Autoimmune hepatitis workup included antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti smooth muscle antibody (SMA) and antiliver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody. The radiological imaging studies, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, ascitic fluid examination, blood and urine culture, arterial blood gas analysis and liver biopsy were done whenever indicated.

The sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score was calculated according to the table in all patients for grading of organ dysfunction. SOFA constitutes the parameters of respiration, coagulation, cardiovascular system, central nervous system, and renal and liver function. The presence of failing organ systems was defined as a SOFA score of three or more points for any individual organ [3]. We also evaluated the possible correlation between outcomes and various clinical and laboratory parameter variables.

Ethical clearance was taken from the institute ethical committee. Written consent was obtained from the parents.

Statistical analysis

For categorical data, we calculated the number and percentages. For comparison of two groups, we applied chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test or Mann–Whitney test, whichever was applicable. To obtain the best predictor for outcome, linear regression analysis was done. We calculated the ROC curve to find sensitivity and specificity of INR and SOFA score.

Results

Of the 31 patients who fulfilled the criteria for ACLF, the mean age was 8.77 ± 3.62 years, with the youngest child aged 2 years and the oldest 16 years; 21 (68.7%) were males and 10 (32.3%) were females, and the male to female ratio was 2.1:1. When we evaluated the etiology of acute deterioration in ACLF, we found that the superadded hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection occurred in 13 (41.9%) and was the most common acute phenomenon. Other causes were hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection and acute AIH flare in three (9.7%) patients each, hepatotoxic drugs in two (6.5%), HBV reactivation in one (3.2%), cholangitis in one (3.2%), upper gastrointestinal bleed in one (3.2%) and undetermined in seven (22.6%) patients. The etiology of underlying CLD was AIH and Wilson disease in thirteen (41.9%) patients each. The other causes were hepatitis B virus (HBV) in two patients (6.5%), Indian childhood cirrhosis (ICC) in one (3.2%) and secondary biliary cirrhosis in two (6.5%). Eight (25.5%) patients had known preexisting CLD without decompensation and 23 (74.5%) presented for the first time with decompensation. The common manifestations of liver failure were jaundice in 31 patients (100%), ascites in 31 (100%), altered sensorium in 18 (58.1%) and upper GI bleed in 8 (25.8%). Ascitic fluid analysis showed evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in nine (29%) patients. The mean interval of onset of jaundice to the development of ascites was 8.28 ± 9.6 days, and jaundice to altered sensorium was 17.52 ± 10.92 days.

The mean hemoglobin, platelet count and INR were 8.59 ± 2.5 g%, 147,903 ± 90,344 and 2.9 ± 1.2, respectively. The mean value of bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and albumin was 12.9 ± 8.9 mg%, 362.2 ± 161, 328.1 ± 280.9, 401.9 ± 291.4 and 2.5 ± 0.6 g/dl, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters: outcomes

| Survival (mean) | Non-survival (mean) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dl) | 8.8 ± 2.3 | 7.8 ± 3.5 | 0.542 |

| TLC (/mm3) | 10557.6 ± 673.6 | 9633.4 ± 3474.9 | 0.903 |

| Platelet (/mm3) | 158,200.1 ± 94,041.7 | 105,000.0 ± 61,507.8 | 0.190 |

| Total bilirubin (mg%) | 12.6 ± 8.7 | 14.8 ± 10.5 | 0.416 |

| INR | 2.7 ± .9 | 4.4 ± 1.4 | 0.001* |

| Total Proteins (gm/dl) | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 5.9 ± .8 | 0.751 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 2.6 ± .7 | 2.4 ± .1 | 0.516 |

| AST (IU/l) | 334.4 ± 299.9 | 478.1 ± 241.7 | 0.174 |

| ALT | 305.8 ± 286.7 | 421 ± 258.02 | 0.208 |

| ALP | 427.9 ± 315.6 | 297.9 ± 134.3 | 0.402 |

TLC total leucocyte count, INR International Normalized Ratio, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALP alkaline phosphatase

* P value <0.05-significant

Outcomes in ACLF

The study showed mortality in 6 (19.4%) and survival in 25 patients (80.6%). The cause of death was multiorgan failure in four and liver failure in two patients. The mean duration between onset of symptom and death was 28.5 days and mean hospital stay was 10.3 days. There was no difference in outcome due to age of the patients (P = 0.191). The mean age in the non-survival group was 7.17 ± 2.71 years and in the survival group 9.16 ± 3.7 years. The effects of underlying CLD and acute events on outcome were not significant. Out of eight patients, upper gastrointestinal bleed was present in three patients in the non-survival group and five patients in the survival group (P value 0.161). Among nine (29%) patients, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was detected in one patient in the non-survival group and eight in the survival group (P = 0.556) (Table 2). The time between onset of jaundice and ascites was 10.25 ± 10.6 days in the non-survival group and 7.95 ± 9.66 days in the survival group, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.618).The time of jaundice to altered sensorium in the non-survival group was 16 ± 11.11 and 18.16 ± 11.28 days in the survival group (P = 0.833) (Table 3). The hematological and biochemical parameters included hemoglobin, total leucocyte count (TLC), platelet count, total bilirubin, serum albumin, total proteins, AST, ALT and ALP levels. There was no significant difference in the survival and non-survival groups.

Table 2.

Outcome of UGIB and SBP

| Total | Survival | Non-survival | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGIB | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0.161 |

| SBP | 9 | 8 | 1 | 0.562 |

UGIB upper gastrointestinal bleed, SBP spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Table 3.

Outcome on the duration of onset of jaundice to ascites, jaundice to altered sensorium, SOFA score and INR

| Outcome | Jaundice to ascites (days) | Jaundice to altered sensorium (days) | SOFA Score | INR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival (Mean ± SD) | 7.9 ± 9.6 | 18.1 ± 11.2 | 5.32 ± 2.015 | 2.7 ± .9 |

| Non-survival (Mean ± SD) | 10.2 ± 10.6 | 16.0 ± 11.11 | 10.33 ± 2.58 | 4.4 ± 1.4 |

| P value | 0.618 | 0.833 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

INR International Normalized Ratio, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment

SOFA score and INR

There was significant difference (P = 0.001) in the mean SOFA score in the non-survival group (10.33 ± 2.58) and survival group (5.32 ± 2.1). The mean value of INR was 2.6 ± 0.9 in the survival group and 4.35 ± 1.37 in the non-survival group, which was also statistically significant (P = 0.001) (Table 4). For the comparison of the two groups, Mann–Whitney test was applied. We evaluated possible correlations between outcomes and 19 variables. The factors that had a significant difference with outcomes were INR and SOFA score.

Table 4.

Predictor outcomes: INR and SOFA score

| P value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Diagnostic Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INR | 0.038 | 100 | 76 | 44.45 | 100 | 80 |

| SOFA Score | 0.001 | 100 | 76.92 | 45.45 | 100 | 80.64 |

INR International Normalized Ratio, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment

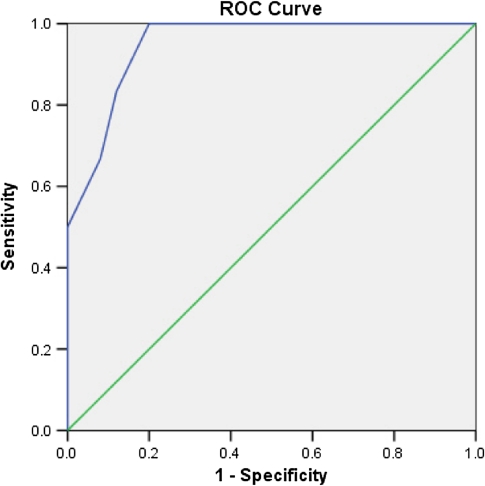

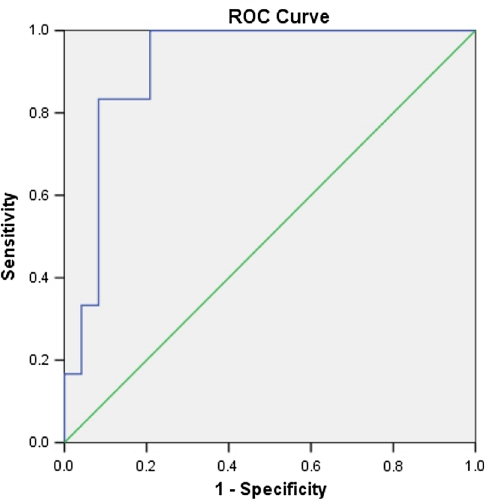

To obtain the best predictor for outcome, linear regression analysis was performed. Multivariate analysis revealed that SOFA score and INR were predictors of survival. The sensitivity of SOFA score was 100%, specificity 92%, positive predictive value 45.45%, negative predictive value 100% and diagnostic accuracy was 80.64% (P = 0.001) (Fig. 1). An INR of 3.05 had a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 76%, positive predictive value of 44.45%, negative predictive value of 100% and diagnostic accuracy of 80% (P = 0.038) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

ROC curve of SOFA score: 0.950 (95% CI 0.876–1.024)

Fig. 2.

ROC curve of INR: 0.917 (95% CI 0.815–1.019)

The study revealed that all patients had Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) grade “C” and the mean CTP score was 12.54.

Discussion

APASL has defined the liver failure in ACLF as jaundice of serum bilirubin >5 mg/dl and coagulopathy, INR more than 1.5 or prothrombin activity less than 40%, which are mandatory with ascites and/or encephalopathy as determined by physical examination [1]. ACLF is a serious disease with very high mortality. There are limited data on predictors of survival in children with ACLF. We prospectively evaluated the predictors of outcome in 31 children with ACLF.

Hepatitis A is the most common cause of hepatitis in children in India and in other developing countries [4–6]. Similarly, the present study also showed superinfection with HAV as the most common (41.9%) cause of acute deterioration in ACLF. In earlier data from our center, the etiology of CLD was viral in 8%, autoimmune in 19%, metabolic including Wilson disease in 21% and unknown in 31% [7]. In the west, hepatitis B associated chronic hepatitis is seen in 92% and metabolic liver disease in less than 2% of children. In our study, AIH, 13 (41.9%), and WD, 13 (41.9%), were the most common causes of CLD. The mean duration of onset of jaundice to development of ascites was 8.28 ± 9.6 days and jaundice to altered sensorium was 17.52 ± 10.92 days.

In this study, 6 patients died (19.4%) and 25 survived (80.6%). Causes of death were multiorgan failure in four and liver failure in two patients. The mean duration between onset of symptoms and death was 28.5 days. In a study by Sarin et al. [8] in an adult population, 44 (69%) patients died in median 45 (2–102) days and the causes of death were multiorgan failure in 64%, liver failure in 27%, gastrointestinal bleed in 7% and hemoperitoneum in 2%.

We evaluated possible correlation between outcomes and 19 variables. The etiology of underlying CLD and acute events, gastrointestinal bleed, SBP, hepatic encephalopathy, platelet count, serum bilirubin and albumin made no significant difference in mortality. The difference in duration of onset of jaundice to ascites and jaundice to altered sensorium in the survival and non-survival group was statistically not significant. The difference in SOFA score and INR in the survival and non-survival group was statistically significant (P = 0.001). Linear regression analysis revealed that SOFA score and INR were predictors of survival. SOFA score of 6.50 and INR of 3.05 were cutoff in predicting mortality with a high sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and diagnostic accuracy. All patients had CTP grade “C” and the mean CTP score was 12.54. A study from Delhi in adults showed that the best predictor of mortality was APACHE-II with an area under ROC curve of 0.78 (95% CI 0.66, 0.90). Survival was significantly different in patients with APACHE-II >10.5 and <10.5 [8].

Jian-Wu et al. [9] showed that the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was the decisive predictor of the prognosis of patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis (AOCH) when the MELD score was over 30. The overall 3-month mortality in patients with AOCH was 74.3%. Radha Krishna et al.’s [10] study found that 44.6% of the patients died and 55.3% survived. Child’s score was higher in non-survivors compared with survivors. The MELD score of 27 was found to be 91% sensitive and 85% specific for predicting the 3-month mortality. In a study from Delhi in adult patients, the predictors of mortality were encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, GI bleed, platelets, serum sodium, HBV DNA and hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) on univariate analysis, whereas on multivariate analysis only encephalopathy, platelet and HVPG independently predicted mortality. Etiology made no difference in mortality [11].

We conclude that ACLF is an important entity in children with definite mortality. Markers of severity should be meticulously looked for if there is suspicion of ACLF. SOFA score and INR are the predictors of outcome.

References

- 1.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Tat Fan S, Garg H, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL) Hepatology Int. 2008;3:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mas A, Rodeg J. Fulminant hepatitis failure. Lancet. 1997;349:1081–1085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, Patch D, Kwong K, Nikolopoulou V, Leandro G, et al. Risk factors, sequential organ failure assessment and model for end-stage liver disease scores for predicting short term mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted to intensive care unit. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Yachha SK, Poddar U, Singh U, Aggarwal R. Does co-infection with multiple viruses adversely influence the course and outcome of sporadic acute viral hepatitis in children? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1533–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendre SV, Bavdekar AR, Bhave SA, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure: etiology, viral markers and outcome. Indian Pediatr. 1999;36:1107–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acharya SK, Dasarathy S, Kumar TL, Sushma S, Prasanna KS, Tandon A. Fulminant hepatic failure in tropical population: clinical course, cause and early predictors of outcome. Hepatology. 1996;23:1148–1155. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathur P, Arora NK, Thapa BR, et al. Metabolic liver disease in childhood: Indian scenario. Indian J Pediatr. 1999;66:S97–S103. doi: 10.1007/BF02752368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Garg HK. Clinical profile of acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) and predictors of mortality: a study of 64 patients [abstract] Hepatology. 2008;48(Suppl):450A. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jian-Wu Y, Gui-Qiang W, Shu-Chen L. Prediction of the prognosis in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis using the MELD scoring system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1519–1524. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radha Krishna Y, Saraswat VA, Das K, Himanshu G, Yachha SK, Aggarwal R, Choudhuri G. Clinical features and predictors of outcome in acute hepatitis A and hepatitis E virus hepatitis on cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2009;29:392–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Das K, Sharma P, Mehta V, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Hemodynamic studies in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Dig Dis Sci 2008 [DOI] [PubMed]