Abstract

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a nonmalignant enlargement of the prostate, can lead to obstructive and irritative lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The pharmacologic use of plants and herbs (phytotherapy) for the treatment of LUTS associated with BPH is common. The extract of the berry of the American saw palmetto, or dwarf palm plant, Serenoa repens (also known by its botanical name of Sabal serrulatum), is one of several phytotherapeutic agents available for the treatment of BPH.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to assess the effects of Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS consistent with BPH.

Search strategy

Trials were searched in computerized general and specialized databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, and The Cochrane Library), by checking bibliographies, and by handsearching the relevant literature.

Selection criteria

Trials were eligible if they (1) randomized men with symptomatic BPH to receive preparations of Serenoa repens (alone or in combination) for at least four weeks in comparison with placebo or other interventions, and (2) included clinical outcomes such as urologic symptom scales, symptoms, and urodynamic measurements. Eligibility was assessed by at least two independent observers.

Data collection and analysis

Information on patients, interventions, and outcomes was extracted by at least two independent reviewers using a standard form. The main outcome measure for comparing the effectiveness of Serenoa repens with placebo or other interventions was the change in urologic symptom-scale scores. Secondary outcomes included changes in nocturia and urodynamic measures. The main outcome measure for side effects or adverse events was the number of men reporting side effects.

Main results

In this update 9 new trials involving 2053 additional men (a 64.8% increase) have been included. For the main comparison - Serenoa repens versus placebo - 3 trials were added with 419 subjects and 3 endpoints (IPSS, peak urine flow, prostate size). Overall, 5222 subjects from 30 randomized trials lasting from 4 to 60 weeks were assessed. Twenty-six trials were double blinded and treatment allocation concealment was adequate in eighteen studies.

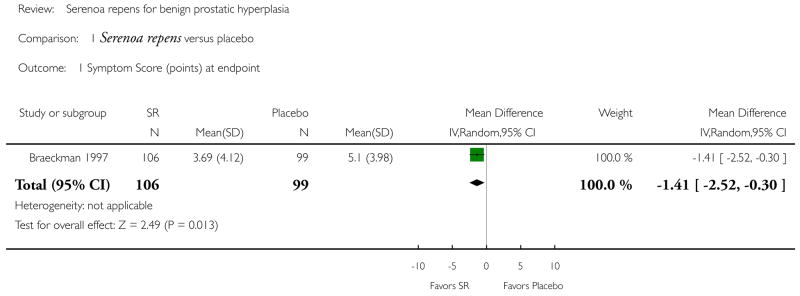

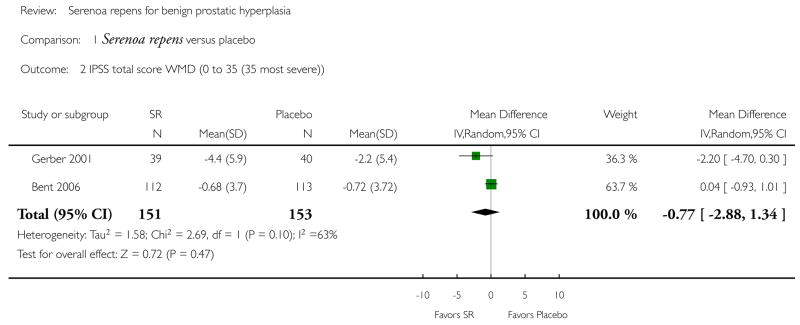

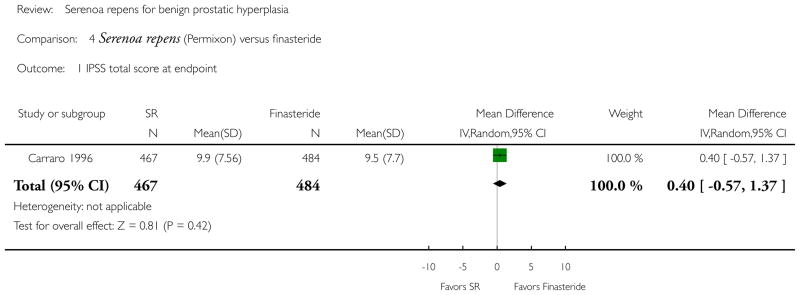

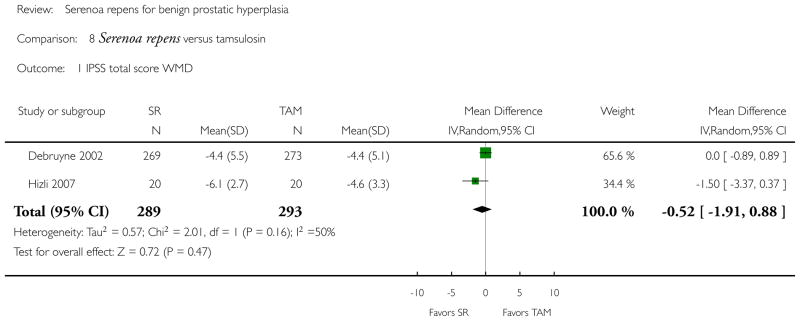

Serenoa repens was not superior to placebo in improving IPSS urinary symptom scores, (WMD (weighted mean difference) −0.77 points, 95% CI −2.88 to 1.34, P > 0.05; 2 trials), finasteride (MD (mean difference) 0.40 points, 95% CI −0.57 to 1.37, P > 0.05; 1 trial), or tamsulosin (WMD −0.52 points, 95% CI −1.91 to 0.88, P > 0.05; 2 trials).

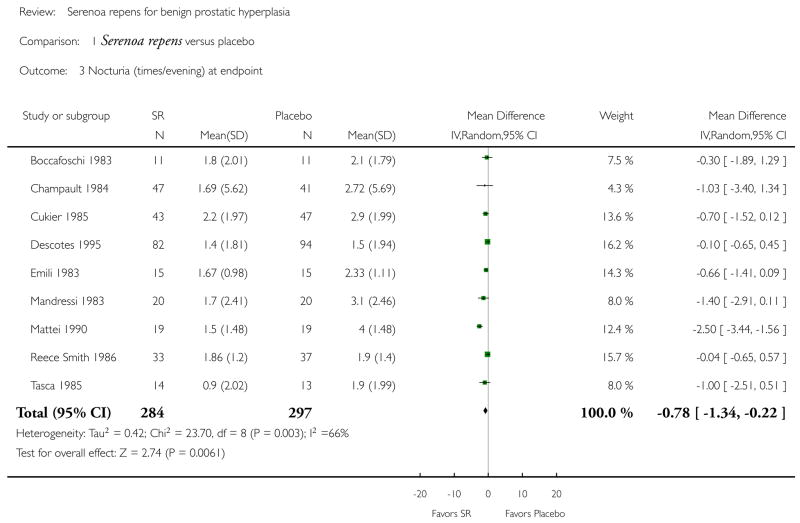

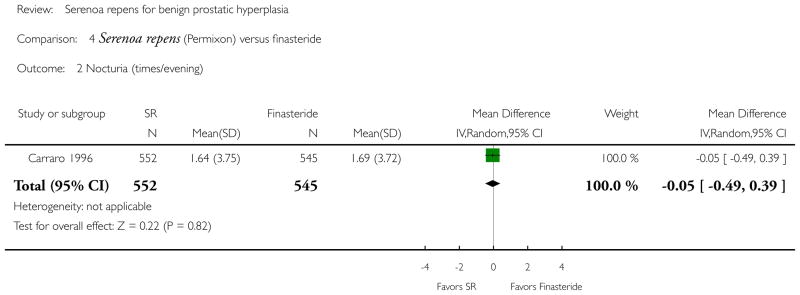

For nocturia, Serenoa repens was significantly better than placebo (WMD −0.78 nocturnal visits, 95% CI −1.34 to −0.22, P < 0.05; 9 trials), but with the caveat of significant heterogeneity (I2 = 66%). A sensitivity analysis, utilizing higher quality, larger trials (≥ 40 subjects), demonstrated no significant difference (WMD −0.31 nocturnal visits, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.08, P > 0.05; 5 trials) (I2 = 11%). Serenoa repens was not superior to finasteride (MD −0.05 nocturnal visits, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.39, P > 0.05; 1 trial), or to tamsulosin (per cent improvement) (RR) (risk ratio) 0.91, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.27, P > 0.05; 1 trial).

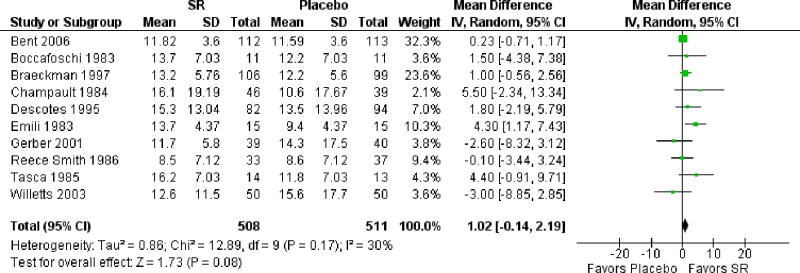

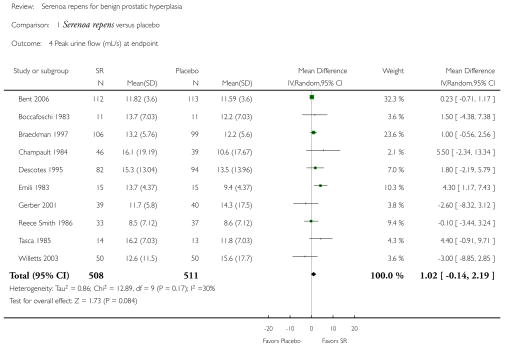

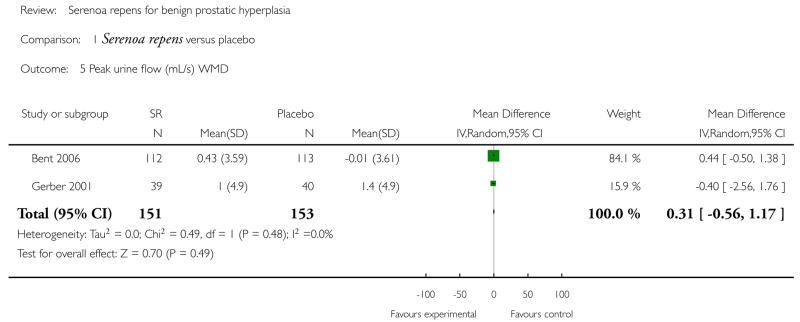

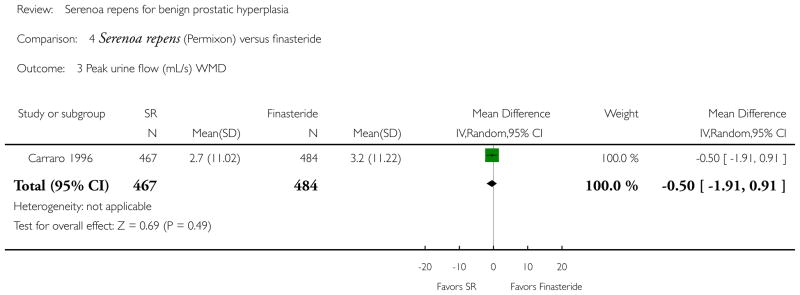

Comparing peak urine flow, Serenoa repens was not superior to placebo at trial endpoint (WMD 1.02 mL/s, 95% CI −0.14 to 2.19, P > 0.05; 10 trials), or by comparing mean change (WMD 0.31 mL/s, 95% CI −0.56 to 1.17, P > 0.05; 2 trials).

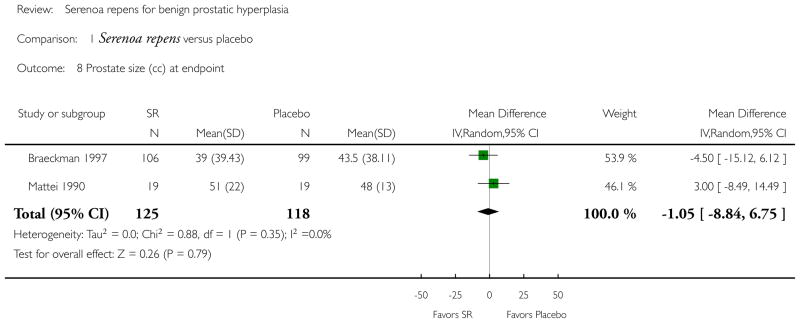

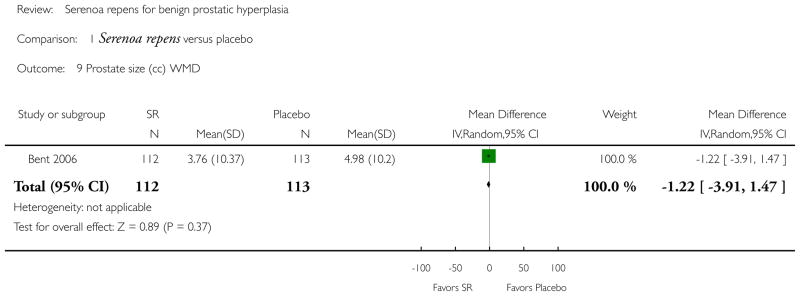

Comparing prostate size at endpoint, there was no significant difference between Serenoa repens and placebo (MD −1.05 cc, 95% CI −8.84 to 6.75, P > 0.05; 2 trials), or by comparing mean change (MD −1.22 cc, 95% CI −3.91 to 1.47, P > 0.05; 1 trial).

Authors’ conclusions

Serenoa repens was not more effective than placebo for treatment of urinary symptoms consistent with BPH.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Phytotherapy, *Serenoa, Androgen Antagonists [*therapeutic use], Plant Extracts [*therapeutic use], Prostatic Hyperplasia [*drug therapy], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Urination [drug effects]

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Serenoa repens, an herbal medicine, provides no improvement in urinary symptoms and peak urine flow for men with benign prostatic hyperplasia

An enlarged prostate gland, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), can interfere with urination, increasing frequency and urge of urinating, or cause problems emptying the bladder. Surgery and drugs are often used to try to treat BPH. However, using herbal medicines in an attempt to relieve BPH symptoms is common. Serenoa repens is an extremely popular herbal medicine for BPH. This review found that Serenoa repens was well tolerated, but was no better than placebo in improving urinary symptom scores. Nor did Serenoa repens provide noticeable relief - generally considered to be a decrease of 3 points - of urinary symptoms.

At this time there have been relatively few high quality long-term randomized studies evaluating standardized preparations of (potentially) clinically relevant doses. Given the frequent use of Serenoa repens and the relatively low quality of existing evidence, a few more well designed, randomized, placebo-controlled studies that are adequately powered, use validated symptom-scale scores, have a placebo arm and a minimum follow up of one year, are needed to confirm, or deny, our new findings.

BACKGROUND

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (see ‘Table of key terms’ (Table 1)) is the nonmalignant enlargement of the prostate gland that is caused by an increase in volume of epithelial and stromal cells into discrete, fairly large nodules in the periurethral region. These nodules in turn can restrict the urethral canal causing partial or complete blockage. Symptoms related to BPH - i.e., lower urinary tract symptoms such as nocturia, incomplete emptying, hesitancy, weak stream, frequency, urgency - are some of the most common problems in older men, and by the seventh decade affect nearly 75% of them (Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors).

Table 1.

Table of key terms

| AUA | The American Urological Association Symptom Score Index, and the same score as the IPSS. These are self-rated, validated (i.e., symptoms that are confirmed clinically) questionnaires that measure the severity of irritative and obstructive urination symptoms. There are seven questions with each question scaled from 0 to 5. A higher score indicates worse symptoms. There are seven questions with each question scaled from 0 to 5. A higher score indicates worse symptoms. | |

| BPH | Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the nonmalignant enlargement of the prostate gland that is caused by an increase in volume of epithelial (top layer of tissue that line cavities and surfaces of the body) and stromal (connective tissue) cells into discrete, fairly large nodules in the periurethral (surrounding the urethra) region. These nodules in turn can restrict the urethral canal causing partial or complete blockage. | |

| Hyperplasia | The proliferation of cells (for BPH, the epithelial and stromal cells) within an organ beyond the ordinary. | |

| IPSS | International Prostate Symptom Score. See AUA. | |

| Peak urine flow | The maximum rate of urine as measured by a uroflowmeter. | |

| Phytosterols | Steroidal alcohols that naturally occur in plants. | |

| Phytotherapy | The use of plants, or plant extracts for medicinal purposes. | |

| Serenoa repens | A small palm native to the American Southeast, Serenoa repens is popularly known as Saw palmetto. When used as a phytotherapy, it is often called Sabal serrulatum. It is the extract of its berries (fatty acids and phytosterols) that is used in the treatment of BPH. | |

| TURP | Transurethral resection of the prostate. A catheter is inserted into the urethra up to the prostate to remove tissue by electrocautery or sharp dissection. |

Histological evidence of BPH is found in more than 40% of men in their fifties and nearly 90% of men in their eighties (Berry 1984), but histologic evidence of BPH, which typically begins in the third decade of life, can be misleading because it does not translate to clinical disease until 20 years later (Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors). Although absolute prevalence rates differ widely in a number of multinational, longitudinal, population-based studies, they are strikingly consistent in age-related increases that parallel Berry’s (Berry 1984) reporting in his biopsy and cadaver study (Platz 2002; Meigs 2001). In 2000 in the US there were approximately 4.5 million visits to physicians that resulted in a primary diagnosis of BPH; in the same year there were nearly 8 million visits that resulted in a primary or secondary diagnosis (Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors). In our 2002 update (Wilt 2002), we reported 300,000 prostatectomies for BPH annually (McConnell 1994); in this update we report slightly more than 87,000 prostatectomies for BPH (Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors). This dramatic decrease in TURPs - formerly the gold standard of practice for severe symptomatic BPH - highlights a trend toward medical management of BPH (Lepor 1996; McConnell 2003). Complementing this trend, phytotherapy has been growing steadily in most countries. Phytotherapeutic agents represent nearly half of the medications dispensed for BPH in Italy, compared with 5% for α-blockers and 5% for 5-ARIs (5α-reductase inhibitors) (Di Silverio 1993). In Germany and Austria, phytotherapy is the first-line treatment for mild to moderate urinary obstructive symptoms and represents more than 90% of all drugs prescribed for the treatment of BPH (Buck 1996). In the United States its use has also markedly increased. In a 2002 survey Serenoa repens (Barnes 2002) was used by 2.5 million adults, “often for BPH.” A recent survey demonstrated that one third of men choosing nonsurgical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia were utilizing herbal preparations alone or in combination with prescription medications (Bales 1999).

There are about 30 phytotherapeutic compounds available for the treatment of BPH, and the most widely used of the plant pharmaceuticals is an extract from the berry of the American saw palmetto or dwarf palm plant, Serenoa repens (also known by its botanical name of Sabal serrulatum). While the mechanism of Serenoa repens is unknown, some of those proposed are: alteration in cholesterol metabolism (Christensen 1990); antiestrogenic and antiandrogenic effects (Dreikorn 1990; Marwick 1995), with Serenoa repens (Permixon®) acting as a weak surrogate 5-ARI, inhibiting the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (Dedhia 2008); anti-inflammatory effects (McGuire 1987; Buck 2004); a decrease in available sex hormone-binding globulin (Di Silverio 1993); pro-apoptotic properties and inhibition of cellular proliferation (Buck 2004; Vacherot 2000; Vela-Navarrete 2005); the dependent inhibition of 5-ARI in the stroma and epithelium of the prostate (Weisser 1996); and the relaxation of smooth muscles via α1-adrenergic receptors.

Despite wide spread use the clinical efficacy of Serenoa repens to improve BPH symptoms and urodynamic measures remains unclear. We conducted and updated a systematic review, first published in 1998 and updated in 2002, to evaluate the efficacy and adverse events of Serenoa repens in men with lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

OBJECTIVES

The main outcomes were the efficacy of Serenoa repens versus placebo or control in improving urologic symptom-scale scores or global report of urinary symptoms (improved versus stable or worsened), and side effects. Secondary outcomes included changes in nocturia, prostate size, and peak urine flow.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized, controlled clinical trials.

Types of participants

Men with lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Types of interventions

Comparison of preparations of Serenoa repens with placebo or medical therapies for BPH with a treatment duration of at least 30 days.

Types of outcome measures

Urologic symptom scores (Boyarsky, American Urologic Association Symptom Index (AUA), and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)); change in peak urine flow; change in prostate size (measured in cubic centimeters (cc)); nocturia (times/per evening); and overall physician or patient assessment of urinary symptoms, or both. If we could not assess mean change, we compared endpoints between or among arms.

(Note: Both the AUA and IPSS use identical the scale of 0 to 35, with mild symptoms scored 1 to 8, medium 9 to 18, and severe ≧ 19.)

Search methods for identification of studies

-

We searched MEDLINE from 1966 to 2008 by crossing an optimally sensitive search strategy for trials from the Cochrane Collaboration with the following MeSH search terms.

prostatic hyperplasia.mp.

phytosterols.mp.

plant extracts.mp.

sitosterols.mp.

serenoa repens.mp.

sabal serrulata.mp.

or/2–6

or/2–6

1 and 7

limit 9 to randomized controlled trial

limit 10 to yr=“2003 – 2008”

from 11 keep 1–10

from 11 keep 1–10

from 13 keep 1–10

and included all subheadings (Dickersin 1994).

EMBASE (1974 to July 2008) and The Cochrane Library, including the database of the Cochrane Prostatic Diseases and Urologic Cancers Group and the Cochrane Field for Complementary Medicine were searched in a similar fashion.

Reference lists of all identified trials and previous reviews were searched for additional trials.

There were no language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility

In this update one reviewer decided on eligibility.

Extraction

Assessment of study characteristics and data extraction were performed by one reviewer. Missing or additional information was sought from authors/sponsors. Extracted data was reviewed by the principal reviewer and discrepancies resolved by discussion.

Assessment of methodological quality

As a measure of overall methodologic study quality (and bias) we assessed scales and criteria developed by Schulz 1995 and Cochrane (Cochrane Handbook 2008). The five criteria addressed were:

adequate sequence generation (was there an articulated rule for allocating interventions based on chance?);

allocation concealment (was there any foreknowledge of the allocation of interventions by anyone?);

blinding (during the course of the trial were study participants and personnel blinded to the knowledge of who received which intervention?);

incomplete outcome data addressed (did the trial assess all patients, or account for those not assessed?);

free of other bias (selective outcome reporting, differences between/among arms in how outcomes were determined).

Each criterion could be answered by A (’yes’), B (’unclear’), and C (’no’).

Summarizing results of primary studies

Outcomes

We assessed the mean urologic symptom score (IPSS, AUA), nocturia (# times), peak urine flow (mL/s), and prostate size (cc). The number and percent of men reporting specific side effects and/or withdrawing from the study were also evaluated.

Meta-analysis

We assessed for heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic.

For the primary analysis (of the stated primary and secondary outcomes) all trials including Serenoa repens in mono-preparations and in combination were analyzed separately (e.g., Serenoa repens versus placebo or active controls, Serenoa repens + Urtica dioica versus placebo or controls). We pooled studies that were deemed clinically similar and provided sufficient information.

Summary effect estimates were done using a random-effects model to allow for heterogeneity between or among studies. Optimally, we would have liked to compare mean changes and variances at endpoint between or among arms. If that data were not available, we compared intergroup endpoints (with variances). Standard errors (SEM) and confidence intervals (CI) that were needed for input to Revman 5 - the Cochrane statistical and systematic review software - were obtained by the following arguments: SD = CI1-CI2 × √n/1.96 and SD = SEM × √N (Follmann 1992).

For continuous outcomes we also used an inverse variance method, which allowed larger trials with smaller SEM more weight over smaller trials with larger SEM, and thus minimizing the uncertainty of the pooled-effect estimate. To assess the per cent of patients having improved - or worsened - urologic symptoms, a modified ITT was performed (i.e., men who dropped out or were lost to follow up were considered to have had worsening symptoms) (Lavori 1992). The denominator for the modified ITT analysis included the number randomized to treatment at baseline and the numerator included the number completing the trial and showing improvement. For dichotomous outcomes we used the Mantel-Haenszel method because we have small trials with little data. For both dichotomous and continuous outcomes, we used 95% CI, and for statistically significant outcomes a P value of ≦ 0.05.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

The updated search strategy (2008) identified 12 new trials, of which 9 met inclusion criteria (Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Engelmann 2006; Bent 2006; Hizli 2007; Shi 2007). Excluded were Pecoraro 2004, Popa 2005, and Vela-Navarrete 2005. Reasons for exclusion were no clinical outcomes (Pecoraro 2004; Vela-Navarrete 2005), and dual publication (Popa 2005).

In this update a total of 2053 additional participants were randomized in 9 trials (820 in trials of Serenoa repens alone or in combination (Urtica dioica, Cernitin®, B-sitosterol, vitamin E, tamsulosin) versus placebo (Preuss 2001; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Shi 2007), and 1233 men in trials of Serenoa repens alone or in combination versus active control (Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Engelmann 2006; Hizli 2007).

Overall (30 studies), mean follow up was 19.1 weeks, and ranged from 4 to 60 weeks. The weighted mean age of all enrollees was 64.9 years (24 studies). Subjects’ age from reporting studies ranged from 43 to 88 years (21 studies). The per cent of men who dropped out or were lost to follow up was 11% (576/5222) and ranged from 0% to 21.4% (30 studies). Only one trial assessed compliance (Shi 2007), which was, after 12 weeks, 98% for the verum arm, and 100% for the placebo arm.

Fourteen trials - including eight new trials for this update -(Metzker 1996; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Lopatkin 2005; Engelmann 2006; Bent 2006; Shi 2007; Hizli 2007) provided efficacy outcomes using validated, self-reporting questionnaires (AUA, IPSS), and which were graded on a 0 (’Never’) to 5 (’Almost always’) scale, for a total score of 35 points. Of the 30 included trials, 12 used Permixon®, a commercialized extract of the fruit of Serenoa repens. Of these twelve, seven compared Permixon® to placebo; the remaining compared Permixon®, either alone or in combination (Permixon® + tamsulosin), to finasteride, tamsulosin, and depostat. Five studies compared another standardized combination of Serenoa repens and (160 mg) and Urtica dioica extracts (120 mg), and which is known by the commercial name Prostagutt® forte, or PRO 160/120. Of these, three compared PRO 160/120 to placebo, one to finasteride, and one to tamsulosin. Fourteen trials used generic Serenoa repens alone or in combination with other phytotherapies (pumpkin seeds, vitamins A and E, nettle root, Pygeum africanum).

Twenty-two of the 30 included trials reported racial data. Ninety-seven per cent of (3205/3309) subjects were White, 0.4% (14/3309) were African American, 0.3% (11/3309) were Hispanic, and 0.6% (21/3309) were Asian/Pacific Islanders. All studies reported regional affiliations; accumulatively, all save three could be dichotomized between Europe and the United States. Ninety per cent (4400/4898) of study subjects were European, and 10% (498/4898) were American.

The weighted mean baseline PSA (8 trials) was 2.9 nanograms/millilitres (ng/mL), and ranged from 1.7 ng/mL to 3.4 ng/mL. The weighted mean baseline prostate volume (11 trials) was 43.9 cc, and ranged from 33 cc to 57 cc.

Overall, symptom-scale score results were reported in 21 studies (Mandressi 1983; Champault 1984; Reece Smith 1986; Gabric 1987; Carbin 1990; Descotes 1995; Carraro 1996; Metzker 1996; Braeckman 1997; Sökeland 1997; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Engelmann 2006; Hizli 2007), but only 14 reported the IPSS or AUA validated scores. Results for nocturia were reported in 14 studies (Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Mandressi 1983; Champault 1984; Cukier 1985; Tasca 1985; Pannunzio 1986; Reece Smith 1986; Carbin 1990; Mattei 1990; Descotes 1995; Carraro 1996; Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002), but only 11 reported data that permitted pooling. Pannunzio presented per cent with nocturia at baseline and endpoint, but without defining nocturia. Debruyne reported per cent improvement, but did not provide baseline values. Peak urine flow was reported in 25 studies (Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Champault 1984; Tasca 1985; Pannunzio 1986; Reece Smith 1986; Gabric 1987; Löbelenz 1992; Descotes 1995; Carraro 1996; Metzker 1996; Braeckman 1997; Sökeland 1997; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Engelmann 2006; Shi 2007; Hizli 2007). Data on prostate size were reported in 13 trials (Emili 1983; Pannunzio 1986; Mattei 1990; Roveda 1994; Carraro 1996; Braeckman 1997; Sökeland 1997; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Debruyne 2002; Bent 2006; Hizli 2007; Shi 2007). Nine trials reported endpoints (Roveda 1994; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Braeckman 1997; Braeckman 1997; Mattei 1990; Mattei 1990; Debruyne 2002; Shi 2007; Hizli 2007), one reported mean change (Bent 2006), and two reported per cent change from baseline (Emili 1983; Pannunzio 1986).

(See ’Characteristics of included studies’ and ’Description of studies’).

Serenoa repens alone or in combination versus placebo

There were 21 trials comparing Serenoa repens, alone or in combination, to placebo (Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Mandressi 1983 (Mandressi was a three-arm trial with placebo and active controls); Champault 1984; Tasca 1985; Cukier 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Gabric 1987; Mattei 1990; Löbelenz 1992; Braeckman 1997; Descotes 1995; Metzker 1996; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Preuss 2001; Gerber 2001; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Shi 2007). Eight trials (Metzker 1996; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Preuss 2001; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Shi 2007) reported baseline values for IPSS total score for a weighted mean of 16.6 points, indicating moderately severe symptoms. Ten trials reported baseline nocturia in some form (Emili 1983; Boccafoschi 1983; Mandressi 1983; Champault 1984; Cukier 1985; Tasca 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Mattei 1990; Descotes 1995; Preuss 2001); eight trials were poolable (Emili 1983; Boccafoschi 1983; Mandressi 1983; Champault 1984; Cukier 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Mattei 1990; Descotes 1995) for a weighted mean of 2.8 incidents per night. Thirteen trials (Emili 1983; Boccafoschi 1983; Tasca 1985; Descotes 1995; Metzker 1996; Braeckman 1997; Bauer 1999; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Bent 2006; Shi 2007) reported baseline peak urine flow for a weighted mean of 11.4 mL/s. This compares closely to Abrams and Griffiths (Abrams 1979) threshold of 10 mL/s or less for intravesical obstruction. The most commonly used dose of Serenoa repens was 160 mg twice daily. Champault reported 80 mg twice daily, Gabric “20 drops” thrice daily, Löbelenz 100 mg once daily, Marks 106 mg twice daily, and Pruess (Serenoa repens + B-sitosterol) 286 mg twice daily.

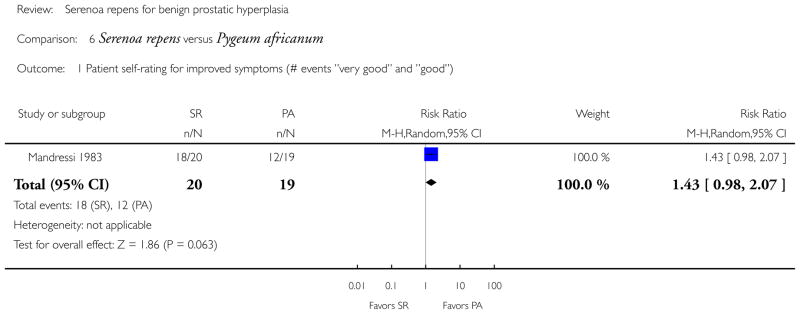

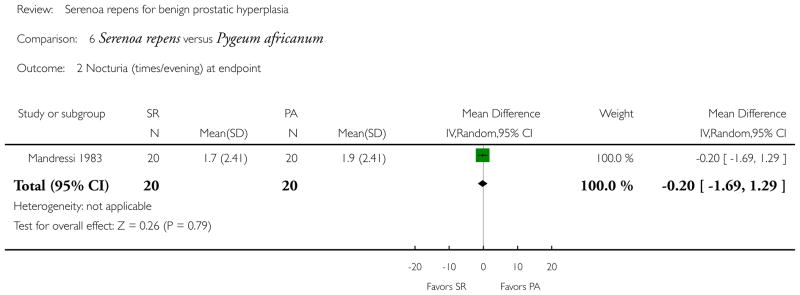

Serenoa repens alone or in combination versus control

Of ten trials comparing Serenoa repens, alone or in combination, with a control (Mandressi 1983; Pannunzio 1986; Carbin 1990; Roveda 1994; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Engelmann 2006; Hizli 2007), five reported baseline values for IPSS total score (Debruyne 2002; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Engelmann 2006; Hizli 2007) of 15.3. Three trials reported nocturia at baseline (Mandressi 1983; Pannunzio 1986; Carbin 1990), but only two trials had poolable data (Mandressi 1983; Carbin 1990) for a weighted mean of 1.93 nocturnal visits. The baseline peak urine flow reported in seven trials (Pannunzio 1986; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Engelmann 2006; Hizli 2007) was a weighted mean of 11.0 mL/s. These results indicate that on average men had urinary symptoms consistent with moderate BPH, with moderate defined as IPSS total score 8 to 19.

Most trials reported doses of Serenoa repens equal to 160 mg twice daily, with the exceptions of Carbin (160 mg thrice daily), Roveda (160 mg 4 times daily), and Engelmann (160 mg daily).

Five studies reported baseline prostate volumes (Roveda 1994; Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Debruyne 2002; Hizli 2007), but only four were able to be pooled. The weighted mean baseline prostate size for the four studies (Carraro 1996; Sökeland 1997; Debruyne 2002; Hizli 2007) was 44.5 cc.

Risk of bias in included studies

Treatment allocation concealment was adequate in 18 studies (60%) (Cukier 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Carbin 1990; Löbelenz 1992; Roveda 1994; Braeckman 1997; Carraro 1996; Metzker 1996; Sökeland 1997; Marks 2000; Gerber 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Engelmann 2006; Bent 2006; Shi 2007), and 26 studies (86.7%) were double blinded (Mandressi 1983; Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Champault 1984; Cukier 1985; Tasca 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Gabric 1987; Carbin 1990; Mattei 1990; Löbelenz 1992; Descotes 1995; Carraro 1996; Metzker 1996; Sökeland 1997; Braeckman 1997; Bauer 1999; Gerber 2001; Preuss 2001; Debruyne 2002; Glémain 2002; Willetts 2003; Lopatkin 2005; Engelmann 2006; Bent 2006; Shi 2007).

The main comparisons were: Serenoa repens monotherapy versus placebo (Mandressi 1983; Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Champault 1984; Cukier 1985; Tasca 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Mattei 1990; Löbelenz 1992; Descotes 1995; Braeckman 1997; Bauer 1999; Gerber 2001; Willetts 2003; Bent 2006; Shi 2007); Serenoa repens in combination with other phytotherapeutic agents versus placebo (Mandressi 1983; Gabric 1987; Carbin 1990; Metzker 1996; Marks 2000; Preuss 2001; Lopatkin 2005); Serenoa repens alone versus control, including Pygeum africanum (Mandressi 1983), gestonorone caproate (Pannunzio 1986), finasteride (Carraro 1996), tamsulosin (Debruyne 2002; Hizli 2007), and Serenoa repens + tamsulosin (Hizli 2007); Serenoa repens in combination with other agents versus control, including Serenoa repens + Urtica dioica versus finasteride (Sökeland 1997), Serenoa repens + tamsulosin versus tamsulosin (Glémain 2002), and Serenoa repens + Uritca dioica versus tamsulosin (Engelmann 2006); and Serenoa repens orally versus Serenoa repens rectally, in a therapeutic, bioequivalence study (Roveda 1994).

Effects of interventions

Serenoa repens versus placebo (n = 14)

Urinary symptom scores

Ten trials reported outcomes for urinary symptom-scale scores comparing Serenoa repens alone versus placebo.

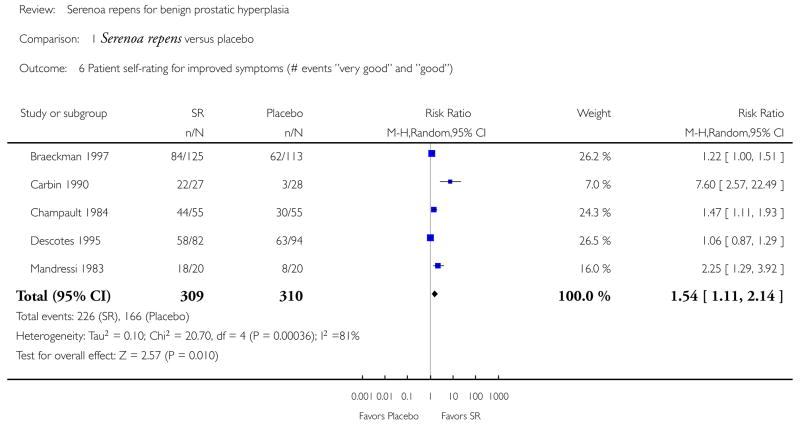

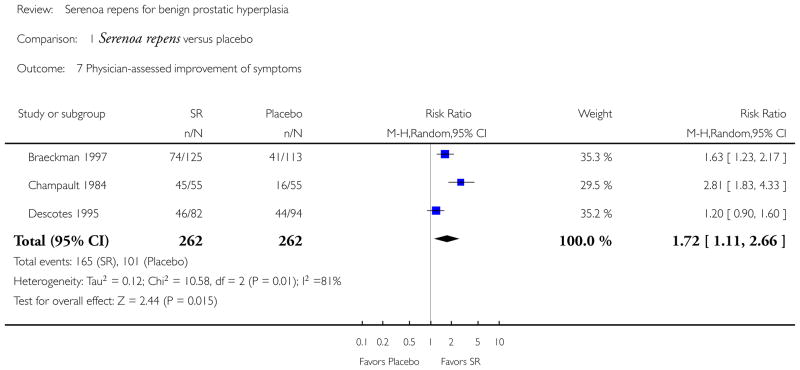

Two trials compared the validated, IPSS total score and found that Serenoa repens was no better than placebo in lowering scores at endpoint (Analysis 1.2). Braeckman 1997 (N = 238), which compared an unidentified, non-validated urinary symptom score (scale 0 to 19) at endpoint, found a significant difference (Analysis 1.1) favoring Serenoa repens. Three trials used a physician-assessed, symptom-improvement score, and found Serenoa repens was significantly better than placebo (Analysis 1.7). In a patient, self-rated survey of improved symptoms, five trials reported Serenoa repens again was significantly better (Analysis 1.6). Reece Smith 1986, in a 12-week trial, compared 11 symptom assessments from both physicians and patients; there were no significant intergroup differences for any symptom in either physician or patient assessments. Willetts 2003 compared IPSS total score from an unequal baseline (t-test, P = 0.028), and reported the Serenoa repens and placebo arms decreased at 12 weeks, but with no significant difference between them (treatment effect 1.74, 95% CI −0.54 to 4.03, P = 0.13).

Gerber did report noticeable relief - considered clinically to be a decrease of three or more points - from symptoms for the Serenoa repens arm (−4.4 points) but not the placebo arm (−2.2 points). Bent found no noticeable relief for either arm (−0.68 points versus 0.72 points, respectively).

Nocturia

Nine trials compared nocturia at endpoint and found Serenoa repens superior to placebo (Analysis 1.3), but with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 66%). A sensitivity analysis, comparing the higher quality, larger trials (N ≧ 40), found no difference (MD −0.31 nocturnal visits, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.08, P > 0.05), and with little heterogeneity (I2 = 11%).

Peak urine flow

Twelve trials (Boccafoschi 1983; Emili 1983; Champault 1984; Tasca 1985; Reece Smith 1986; Löbelenz 1992; Braeckman 1997; Descotes 1995; Bauer 1999; Gerber 2001; Willetts 2003; Bent 2006) presented data for peak urine flow, but only 10 had poolable data. There was no significant difference at endpoint (Analysis 1.4). Gerber 2001 and Bent 2006 compared mean change and found no difference as well (Analysis 1.5).

Three trials reported data that were not poolable (Bauer 1999; Löbelenz 1992; Willetts 2003). Bauer found a 12% absolute improvement for Serenoa repens, and Löbelenz a 5.2% absolute improvement favoring Serenoa repens. Willetts reported a significant difference, favoring placebo (t-test, P < 0.05).

Prostate size

Five trials (Emili 1983; Mattei 1990; Braeckman 1997; Bauer 1999; Bent 2006) reported data for prostate size, but only two were poolable (Mattei 1990; Braeckman 1997). Both trials reported slight decreases for both arms, but nevertheless found no significant difference at endpoint (Analysis 1.8). Bauer (N = 101), with a follow up of six months, reported a slight increase for both arms. For Serenoa repens, the increase was 1.4% (34.5 cc to 35 cc), and for the placebo arm, 1.5% (31.7 cc to 32.2 cc). Emili (N = 30), with a four-week follow up, reported (in a qualitative scale) 26.6% reduction for the Serenoa repens arm, and no change for the placebo arm. Bent (N = 225), with a follow up of 12 months, reported size increases for both arms at endpoint for a mean difference of −1.22 cc (95% CI −3.91 to 1.47, P > 0.05).

Serenoa repens versus finasteride (n = 1)

Urinary symptom scores

Carraro 1996 (N = 1098) found no difference between Serenoa repens and finasteride in the IPSS total score at endpoint (MD 0.40 points, 95% CI −0.57 to 1.37, P > 0.05).

Nocturia

Serenoa repens was not superior to finasteride (−0.05 nocturnal visits, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.39, P > 0.05).

Peak urine flow

There was no difference between Serenoa repens and finasteride (MD −0.50 mL/s, 95% CI −1.91 to 0.91, P > 0.05).

Prostate size

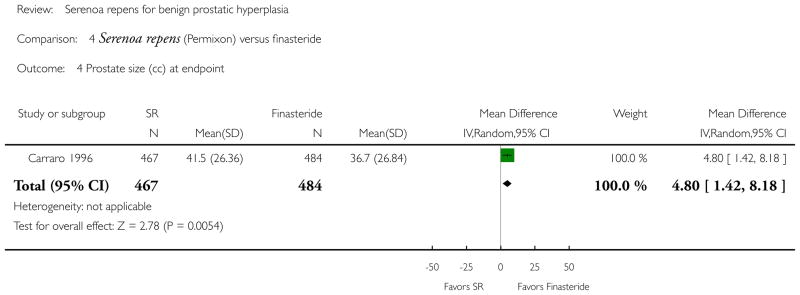

Carraro (mean prostate size 43.5 cc) reported both treatments reduced prostate size over a 13-week follow up. In the Serenoa repens arm, prostate size changed from 43.0 cc to 41.5 cc (−6%) and in the finasteride arm, 44.0 cc to 36.7 cc (−18%). The difference was significant (WMD 4.80 cc, 95% CI 1.42 to 8.18, P < 0.05) and favored finasteride.

Serenoa repens versus tamsulosin (n = 2)

Urinary symptom scores

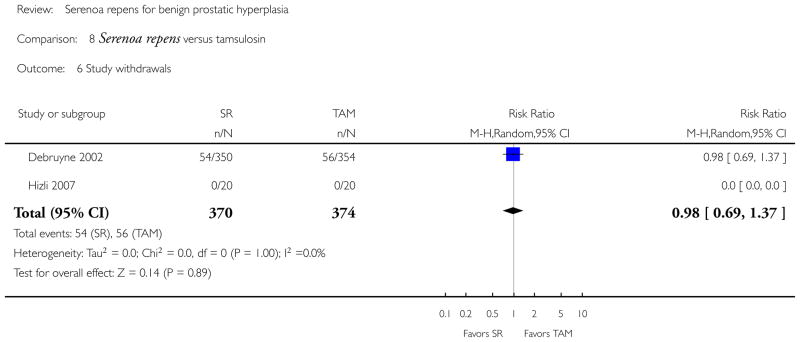

There was no significant difference in IPSS total score (tamsulosin dose for both trials was 0.4 mg daily) (Analysis 8.1). In contrast to Serenoa repens versus placebo (P > 0.05), these two trials showed comparable efficacy.

Nocturia

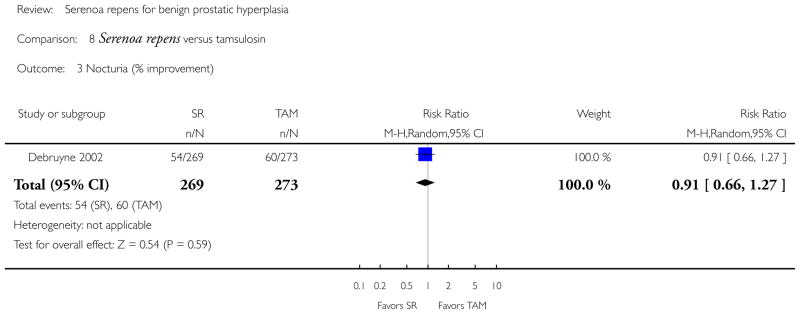

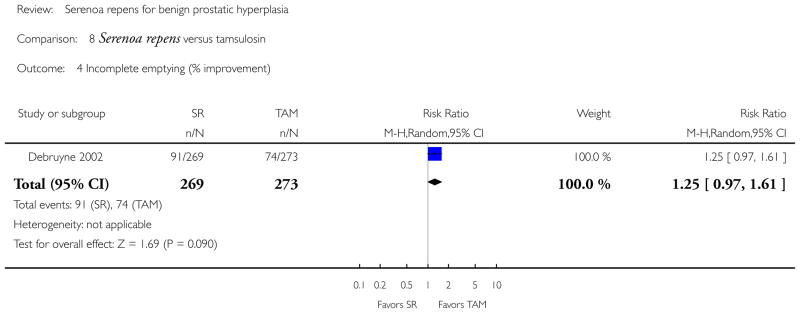

Debruyne 2002 reported no significant difference comparing per cent improvement (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.27, P > 0.05).

Peak urine flow

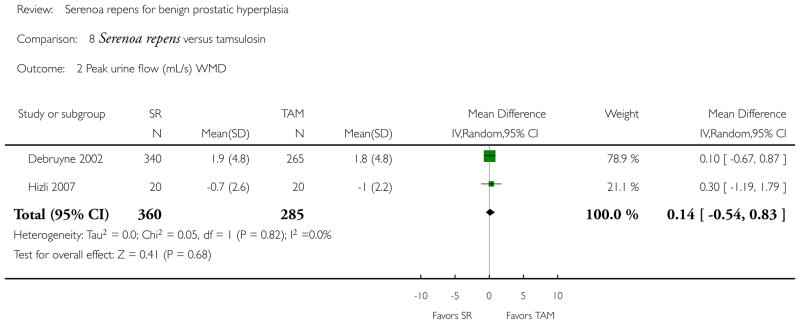

Debruyne found slight increases in peak urine flow and Hizli slight decreases, but in the meta-analysis there was no significant difference (Analysis 8.2).

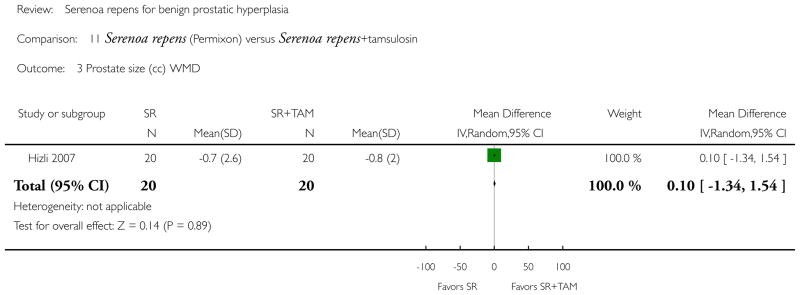

Prostate size

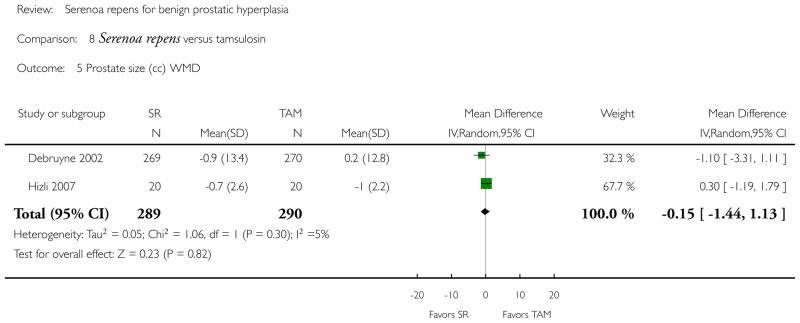

Both trials reported shrinking prostates for all arms save a single tamsulosin arm. No difference was found in the meta-analysis (Analysis 8.5).

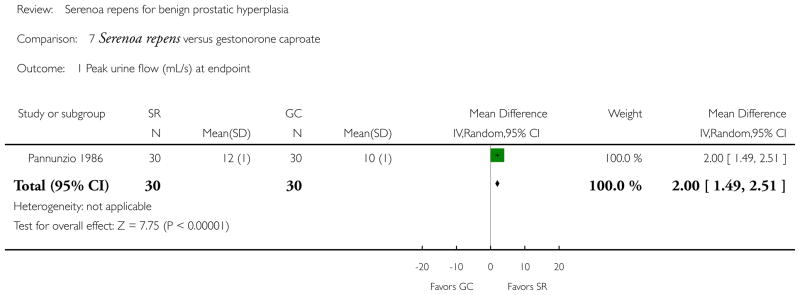

Serenoa repens versus gestonorone caproate (n = 1)

Peak urine flow

Pannunzio (N = 60) reported a significant difference in mean change, favoring Serenoa repens (MD 2.00 mL/s, 95% CI 1.49 to 2.51, P < 0.05).

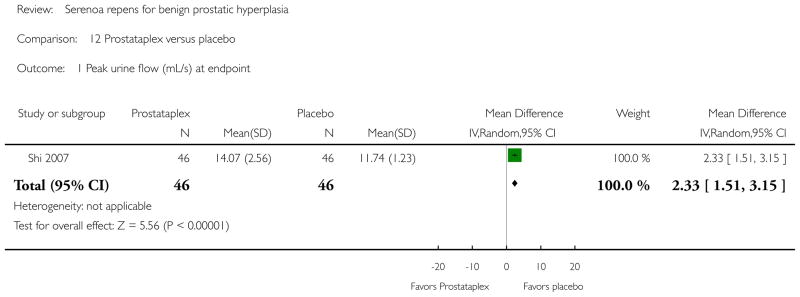

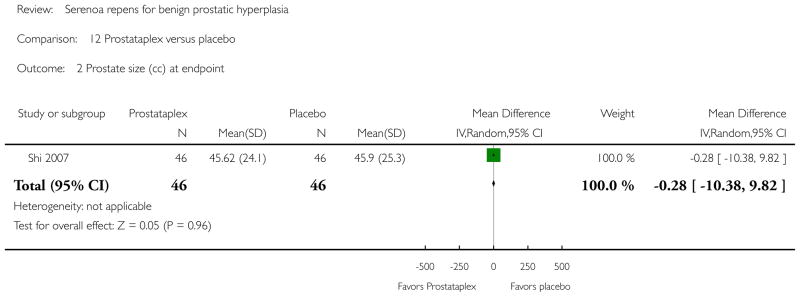

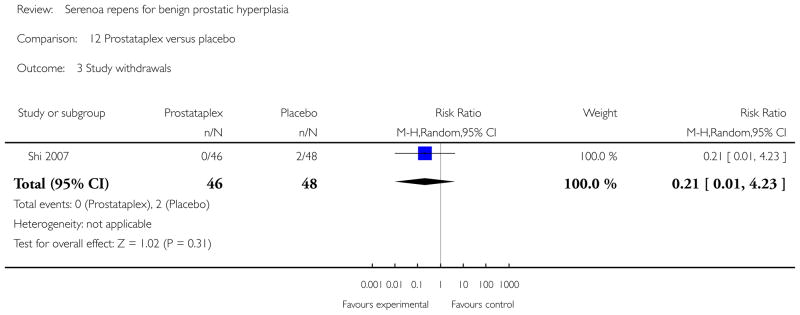

Prostataplex™ (Serenoa repens, soybean oil, beeswax, soy lecithin, gelatin, glycerin, deionized water, titanium dioxide, carmine red, natural vanilla flavor) versus placebo (N = 1)

Urinary symptom score

Shi 2007 (N = 94) considered an a priori intra group decrease of three points of the IPSS total score to be clinically significant. After a three-month follow up, the Prostataplex™ arm decreased a mean of 2.02 points, and the placebo arm decreased a mean of 0.33 (Student’s t-test, P < 0.001). The comparison of endpoints (14.83 versus 14.13, respectively) was not significant (Student’s t-test, P = 0.545).

Peak urine flow

Shi reported a significant difference at endpoint. The WMD was 2.33 mL/s (95% CI 1.51 to 3.15, P < 0.05), favoring Prostataplex™.

Prostate size

Shi reported slight decreases at endpoint (SR = 2.1 cc; placebo = 2.48 cc).

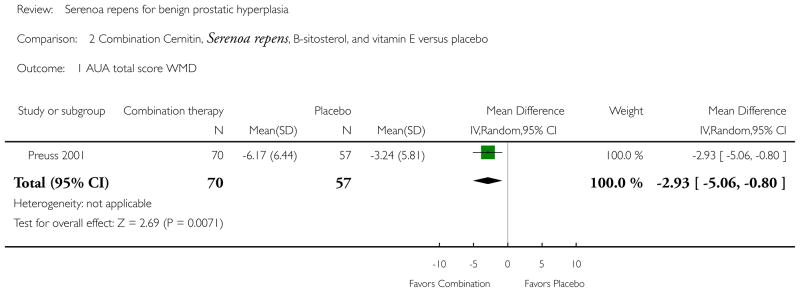

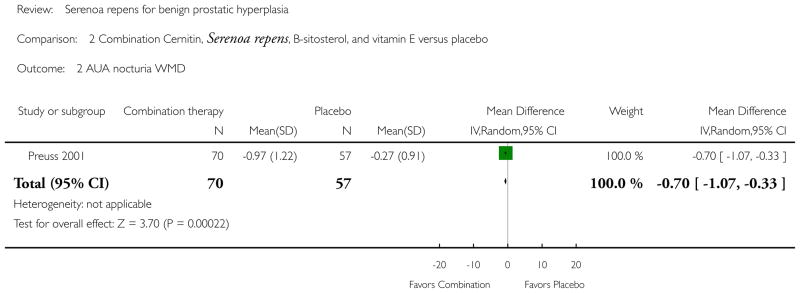

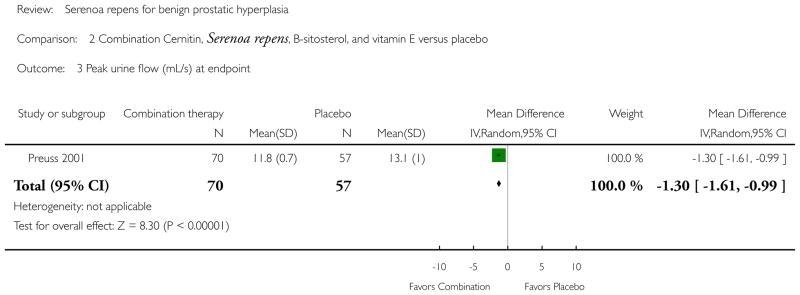

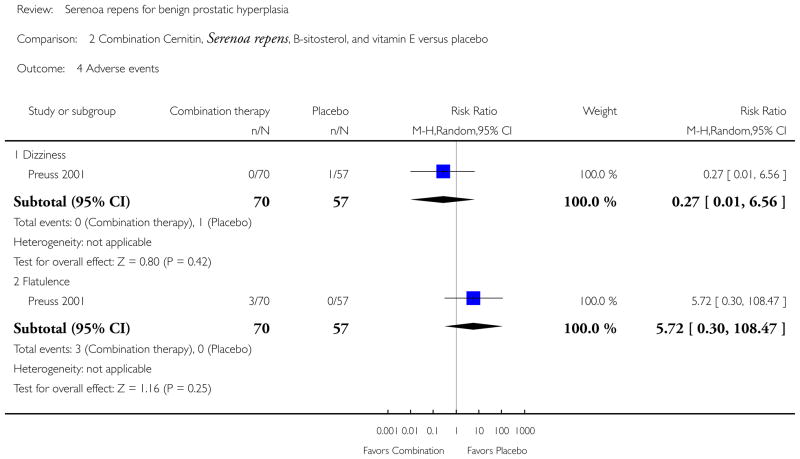

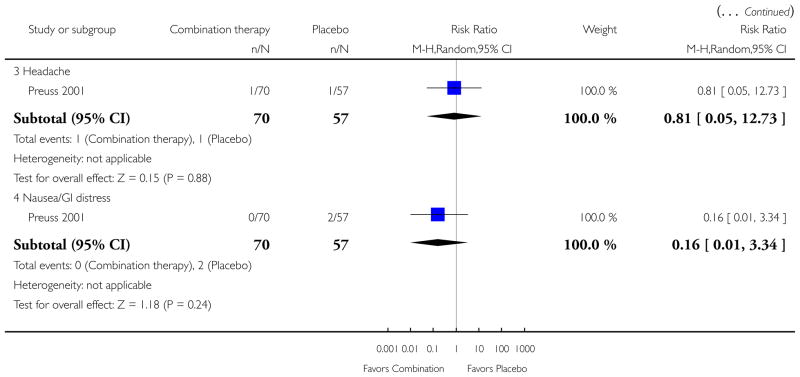

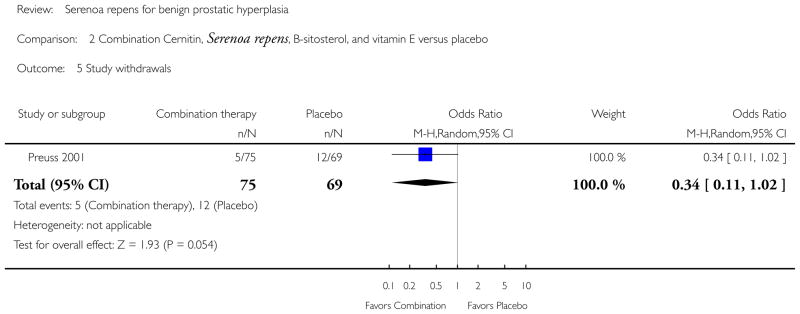

Combination Cernitin®, Serenoa repens, B-sitosterol, vitamin E versus placebo (n = 1)

Urinary symptom scores

Preuss 2001 (N = 144) reported a significant difference in the AUA total score (MD −2.93 points, 95% CI −5.06 to −0.80, P < 0.05) in favor of combination therapy.

Nocturia

Preuss found a significant difference between the two arms in the AUA nocturia subscale (0 to 5; ’0’ is no trips, ’5’ is 5 trips or more) (MD −0.70, 95% CI −1.07 to −0.33, P < 0.05).

Peak urine flow

Combination therapy was superior to placebo at endpoint (MD −1.30 mL/s, 95% CI −1.61 to −0.99, P < 0.05).

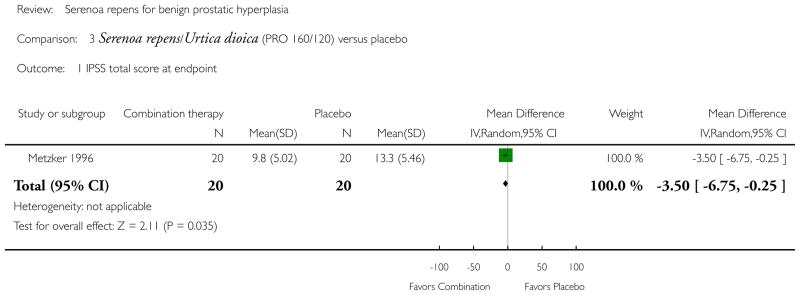

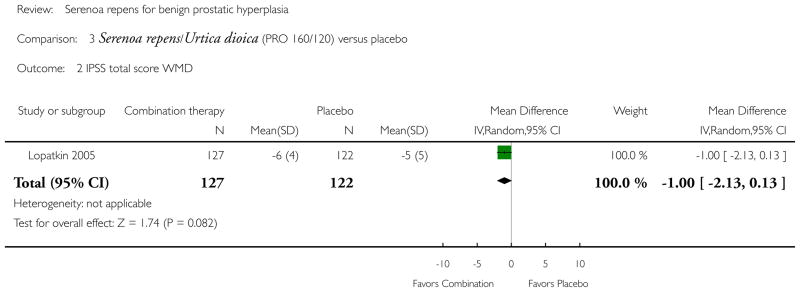

Serenoa repens/Urtica dioica versus placebo (n = 3)

Urinary symptom scores

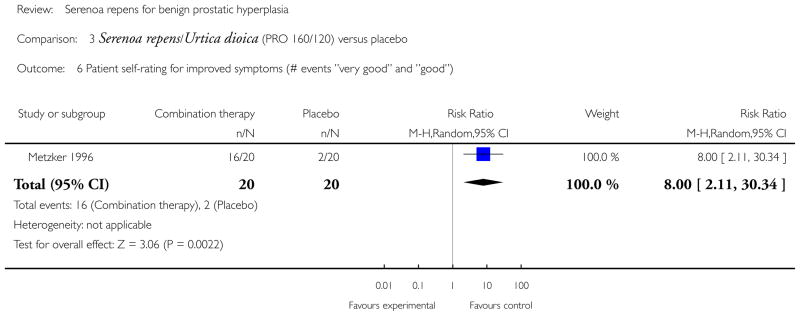

Metzker 1996 (N = 40) found a significant difference in IPSS endpoint (40-week follow up) (MD −3.50 points, 95% CI −6.75 to −0.25, P < 0.05); Lopatkin 2005 (N = 257), comparing mean change, did not (MD −1.00 points, 95% CI −2.13 to 0.13, P > 0.05). Gabric 1987 (N = 30) compared the combination Prostagutt® forte to placebo, and included a physician evaluated global symptom score (scale 1 to 3; 1 = no change, 2 = satisfactory change, 3 = excellent change) at six-week endpoint. The median (extrapolated from graph) for the verum arm was 1.3 and for the placebo arm 2.2 (P < 0.05).

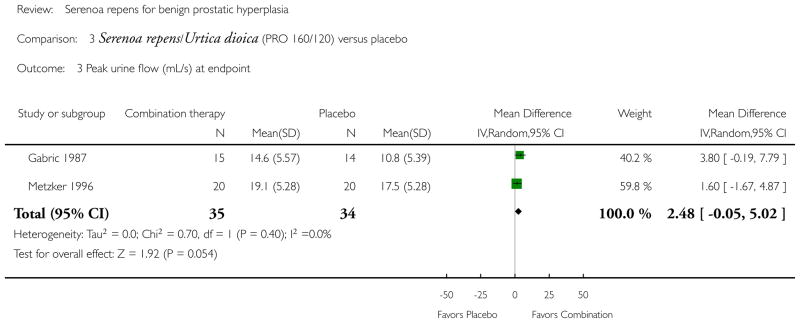

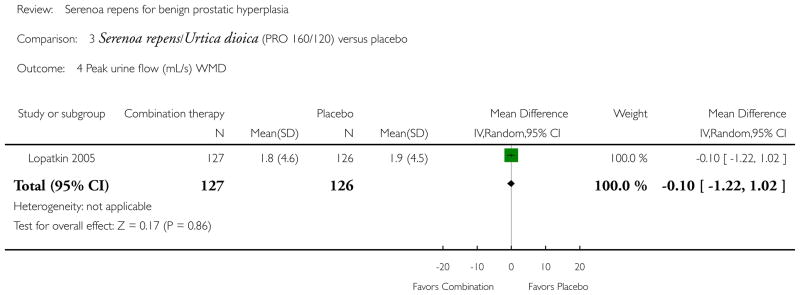

Peak urine flow

Lopatkin, comparing mean change, reported positive mean changes of about 2 mL/s for both arms, but the comparison was not significant (MD −0.10 mL/s, 95% CI −1.22 to 1.02, P > 0.05). Gabric 1987 (N = 30) and Metzker found a significant difference at endpoint (Analysis 3.3).

Serenoa repens/Urtica dioica versus finasteride (N = 1)

Urinary symptom scores

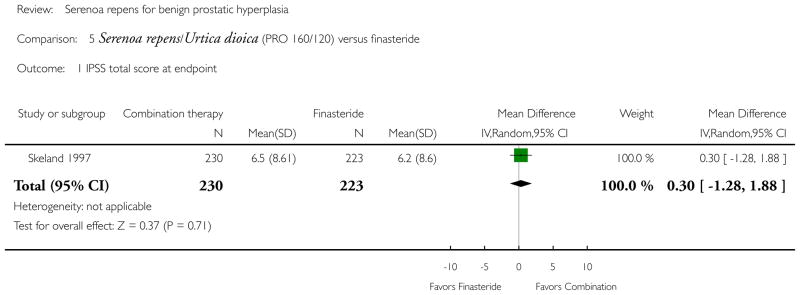

Sökeland 1997 (N = 543) found no significant difference in IPSS total score at 12-week endpoint (MD 0.30 points, 95% CI −1.28 to 1.88, P > 0.05).

Peak urine flow

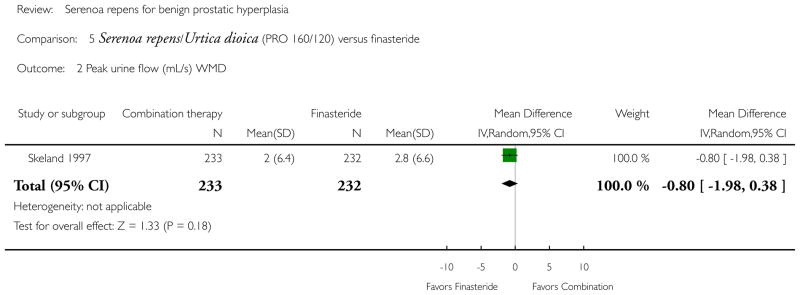

Sökeland reported increases of 2.7 mL/s and 3.2 mL/s for Serenoa repens/Urtica dioica and placebo, respectively, but the comparison was not significant (MD −0.80 mL/s, 95% CI −1.98 to 0.38, P > 0.05).

Prostate size

Sökeland (mean prostate size 43.3 cc) reported declines in prostate volume for both arms at the end of 12-week follow up. The PRO 160/120 arm decreased 0.7% (42.7 cc to 42.4 cc), and the finasteride arm, 15.5% (44.0 cc to 37.2 cc), for an absolute improvement of 14.8% favoring finasteride.

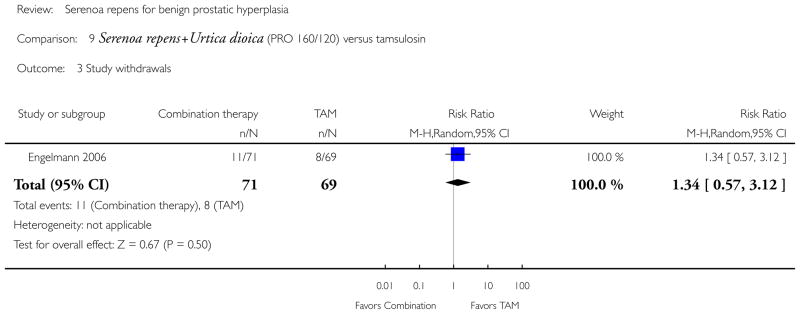

Serenoa repens/Urtica dioica versus tamsulosin (N = 1)

Urinary symptom scores

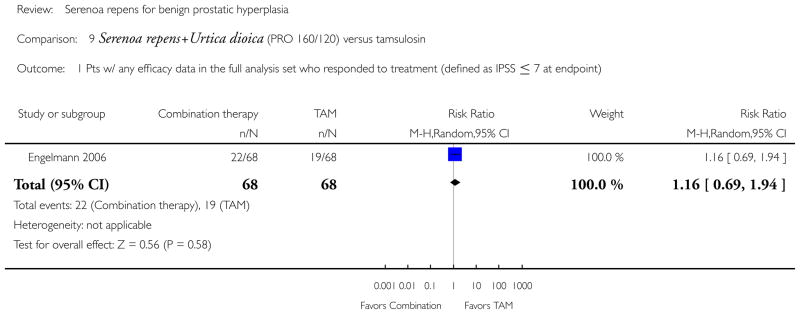

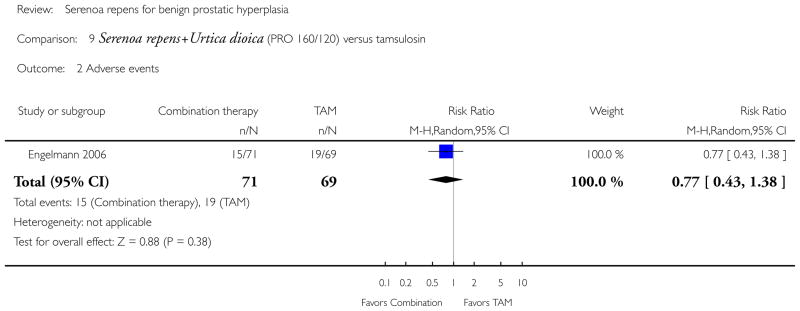

Engelmann 2006 (N = 140), which reported responders to treatment (defined as IPSS ≧ 7 at endpoint), found no significant difference between the arms (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.94, P > 0.05).

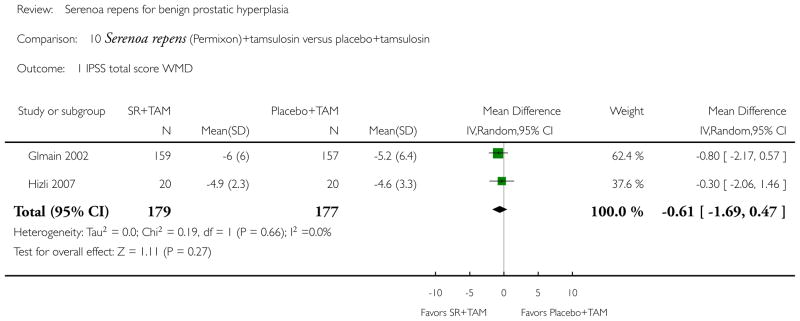

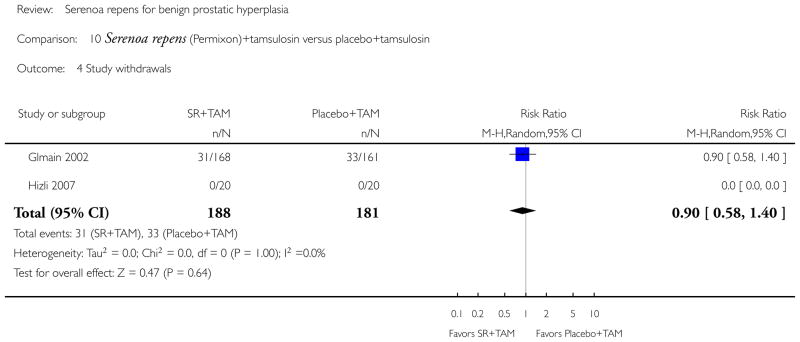

Serenoa repens + tamsulosin versus tamsulosin (dose 0.4 mg daily for both studies) (N = 2)

Urinary symptom scores

Glémain 2002 and Hizli 2007, comparing IPSS total scores, found increases in all arms, but the difference was not significant (Analysis 10.1).

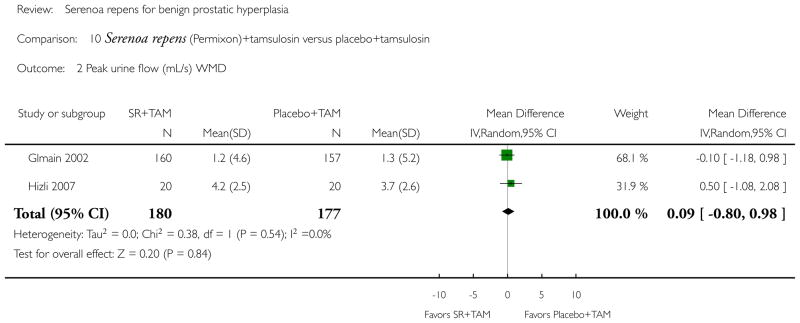

Peak urine flow

Glémain (N = 325) and Hizli (n = 40 in this comparison) reported positive changes in all arms, but no statistical difference (Analysis 10.2).

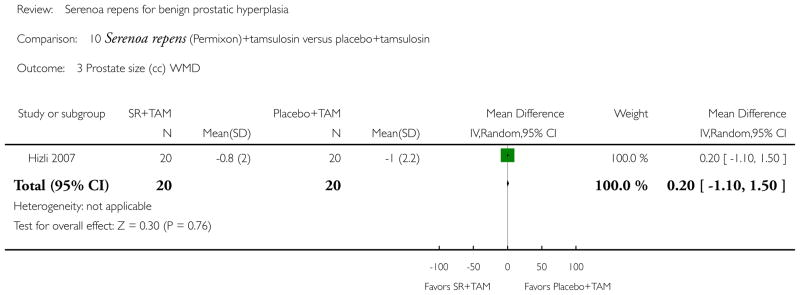

Prostate size

Hizli (n = 40 for these comparisons), in a 24-week study, also reported no significant difference in mean change (MD 0.20 cc, 95% CI −1.10 to 1.50, P > 0.05).

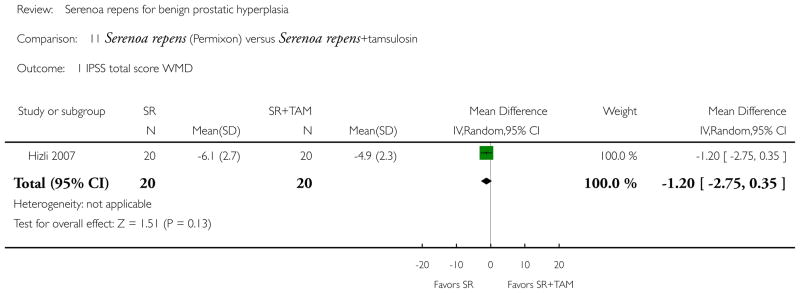

Serenoa repens versus Serenoa repens + tamsulosin (N = 1)

Urinary symptom scores

Hizli 2007 reported no difference in IPSS total score mean change (MD −1.20 points, 95% CI −2.75 to 0.35, P > 0.05).

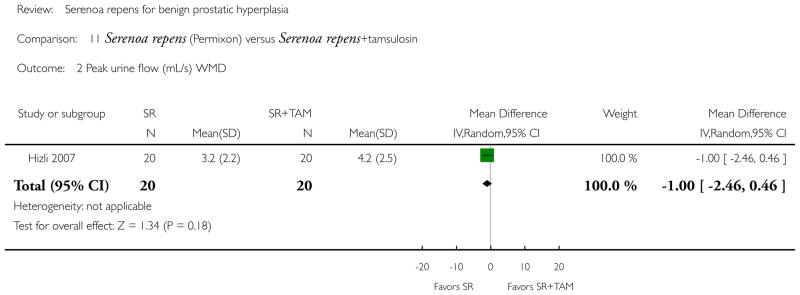

Peak urine flow

There was no significant difference in mean change (MD −1.00 mL/s, 95% CI −2.46 to 0.46, P > 0.05).

Prostate size

Although both treatments shrank the prostate, Serenoa repens monotherapy was not significantly better than combination therapy (MD 0.10 cc, 95% CI −1.34 to 1.54, P > 0.05).

Peak urine flow

Both arms increased peak urine flow, but monotherapy was not significantly better (MD −1.00 mL/s, 95% CI −2.46 to 0.46, P > 0.05).

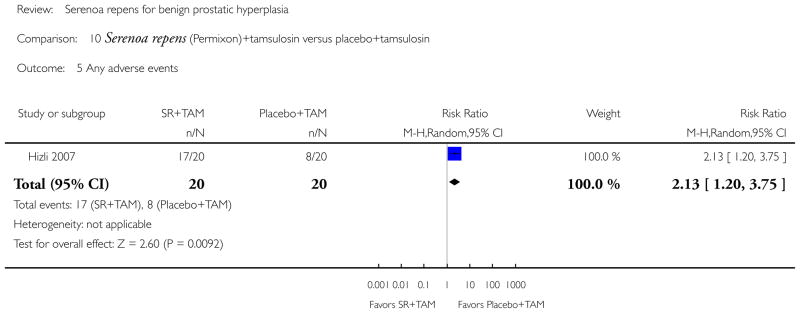

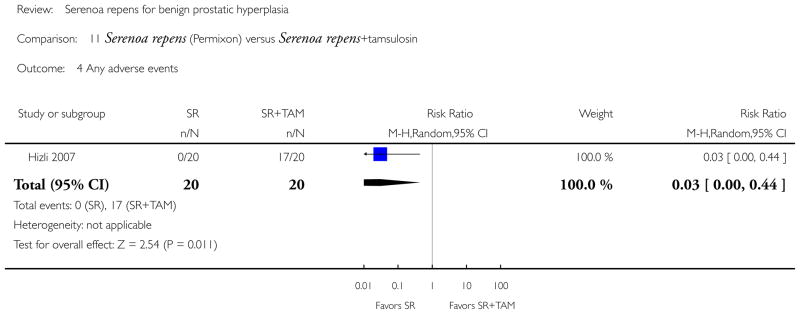

Adverse effects and adverse events

We assessed adverse effects associated with Serenoa repens and active controls (alpha-blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors). For the 19 trials reporting, adverse effects were generally mild. The most common adverse effects associated with Serenoa repens, finasteride, and tamsulosin were asthenia (abnormal loss of strength), decrease in libido, diarrhea, dizziness, ejaculation disorders, gastrointestinal distress, headaches, and postural hypotension. Versus placebo, no arm reported an incidence of adverse effects greater than 5% None of the comparisons was statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary table of adverse effects (SR vs placebo)

| * SR | Placebo | Comparisons P = 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | |||

| Dizziness | 10/349 (3) (1 trial) | 1/56 (2) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Gastrointestinal distress | 30/665 (5) (2 trials) | 3/169 (2) (2 trials) | P = NS |

| Headache | 35/900 (4) (2 trials) | 1/56 (2) (1 trial) | P = NS |

Denominator is number in arm.

Serenoa repens.

Per cents are rounded to the nearest tenth. NS = not statistically significant.

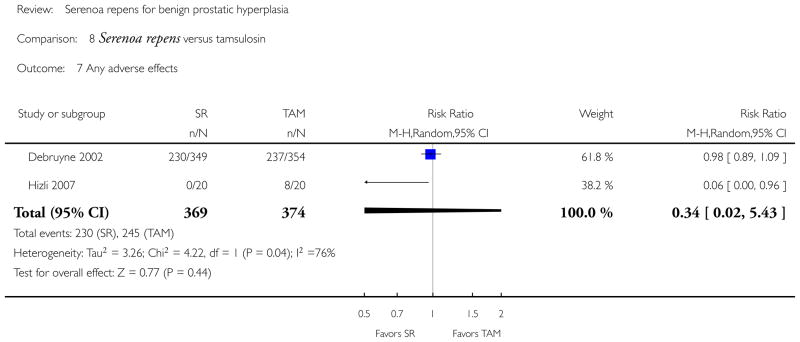

Incidences of asthenia, decrease in libido, dizziness, ejaculation disorders, headache, postural hypotension were most commonly reported in the trials versus tamsulosin. Headache and ejaculation disorders were statistically significantly greater in the tamsulosin arm compared to the Serenoa repens arm (10% versus 4%, and 4% versus 1%, respectively) (Table 3). The RR for any adverse event was 0.34 (95% CI 0.02 to 5.43) (2 studies) (Analysis 8.7).

Table 3.

Summary table of adverse effects (SR vs tamsulosin)

| * SR | § TAM | Comparisons P = 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | |||

| Asthenia | 10/349 (3) (1 trial) | 10/354 (3) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Decrease in libido | 13/890 (1) (2 trials) | 4/354 (1) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Dizziness | 10/349 (3) (1 trial) | 6/354 (2) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Ejaculation disorders | 2/349 (1) (1 trial) | 15/354 (4) (1 trial) | P < 0.05 |

| Headache | 35/900 (4) (2 trials) | 37/354 (10) (1 trial) | P < 0.05 |

| Postural hypotension | 4/349 (1) (1 trial) | 3/354 (1) (1 trial) | P = NS |

Denominator is number in arm.

Serenoa repens.

Tamsulosin.

Per cents are rounded to the nearest tenth. NS = not statistically significant.

Compared to finasteride, reported adverse effects included decrease in libido, diarrhea, gastrointestinal distress, and headache. The most common adverse effect reported for Serenoa repens was gastrointestinal distress (5%). The most common adverse effect for finasteride was diarrhea (11%). Only headache was statistically significantly greater in the Serenoa repens arm (4% versus < 1%), (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary table of adverse effects (SR vs finasteride)

| * SR | ❡FIN | Comparisons P = 0.05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease in libido | 13/890 (1) (2 trials) | 16/542 (3) (1 trial) | P = 0.06 |

| Diarrhea | 5/551 (1) (1 trial) | 6/542 (11) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Gastrointestinal distress | 30/665 (5) (2 trials) | 15/542 (3) (1 trial) | P = NS |

| Headache | 35/900 (4) (2 trials) | 2/542 (< 1) (1 trial) | P < 0.05 |

Denominator is number in arm.

Serenoa repens.

Finasteride.

Per cents are rounded to the nearest tenth. NS = not statistically significant.

Serious adverse events (i.e., events with no necessary causal association with the intervention) were reported in the Bent trial comparing Serenoa repens to placebo (Bent 2006). These events included cardiovascular event, elective orthopedic surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding, bladder cancer, colon cancer, elective hernia repair, hematoma, melanoma, prostate cancer, shortness of breath, and rhabdomyolysis. The Serenoa repens arm had 8 (7%) serious adverse events, and 18 (16%) were reported for the placebo arm (P = 0.05).

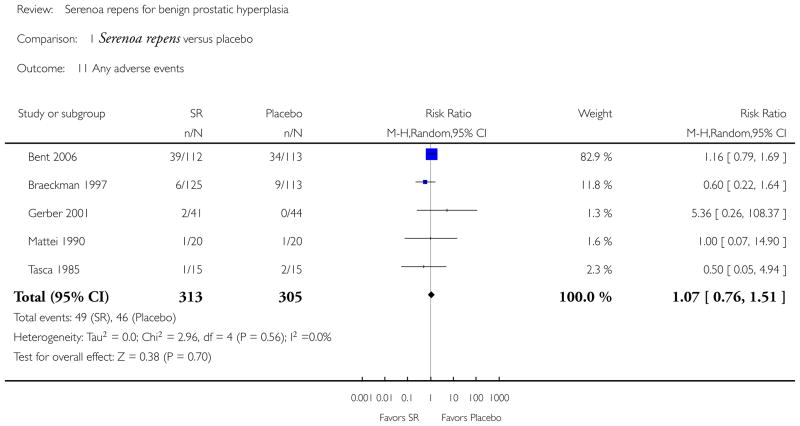

In a meta-analysis (5 studies) of ’any’ adverse event, and which included both causal and non-causal harms, there was no difference between the verum and the placebo arms (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.51 (Analysis 1.11).

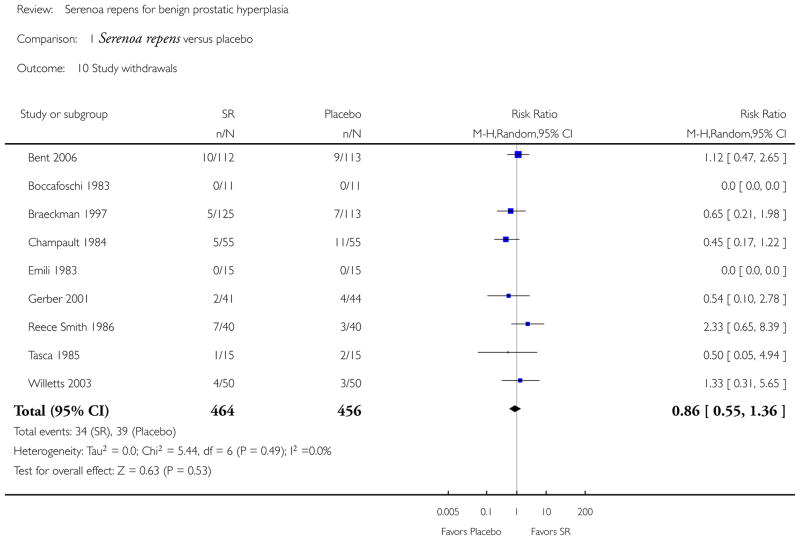

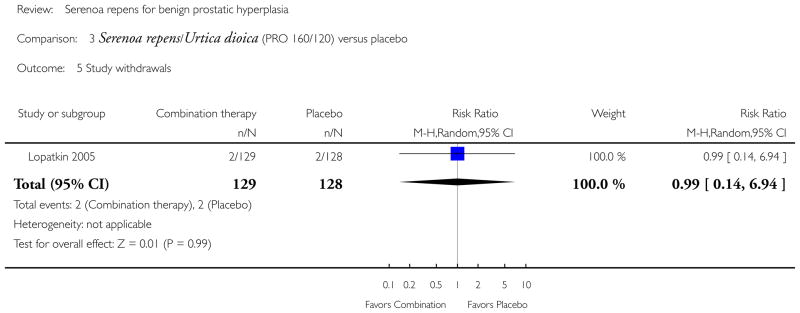

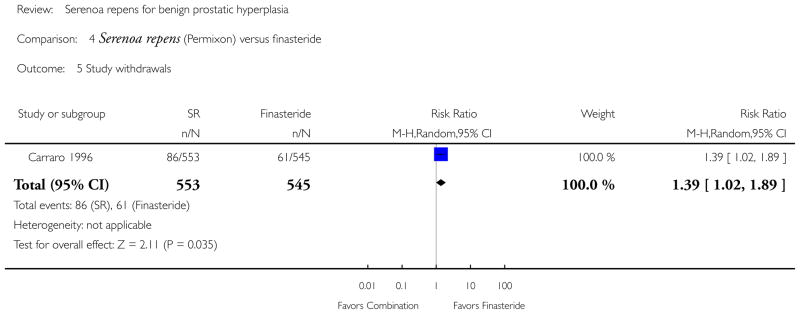

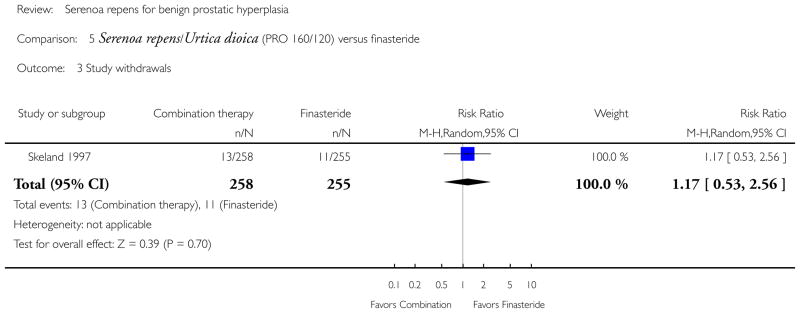

Study withdrawals

All 30 trials reported losses to follow up. The comparison of studies with a Serenoa repens monotherapy arm (n = 15, 175/1483) to trials with a placebo arm (n = 13, 60/721) was 11.8% versus 8.3%, respectively. The RR was 1.42 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.88, P = 0.01), favoring placebo. The tamsulosin (n = 4, 97/624) arms reported a 15.5% withdrawal rate (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.91, P = 0.01), and favored Serenoa repens monotherapy. Finasteride (n = 2, 72/800) had a 9% rate (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.70, P = 0.04) and favored finasteride.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

We “assess[ed] the effects of Serenoa repens in the treatment of LUTS consistent with BPH” (Wilt 1998). In 1998 and again in 2002 (Wilt 2002), we reported, after evaluating mostly under-powered, short-term trials with variable study design, outcomes, and non-validated symptom-scale scores, that Serenoa repens provided mild improvement of urologic symptoms and flow measures. In this 2008 update we have attenuated our conclusions. In a meta-analysis comparing Serenoa repens to placebo, two trials (Gerber 2001; Bent 2006) reported mean change of the validated IPSS total score. Both trials were well designed and one was adequately powered. Gerber randomized 85 subjects with a follow up of 6 months and a mean age of 65 years. Bent enrolled 225 subjects with a mean age of 63 years in a 12-month trial. The WMD was −0.77 points (95% CI −2.88 to 1.34, P > 0.05). The difference was small and not statistically significant in both studies as well as the pooled analysis. Therefore the two highest quality studies show no substantive benefit versus placebo.

For a consumer looking to see if Serenoa repens offers relief of symptoms for BPH, the evidence is somewhat mixed. In our intra group analysis of the efficacy of Serenoa repens monotherapy, which is generally considered in a clinical setting to be a decrease of three points or greater, we found four trials that reported full data. Three of the four (Gerber; Debruyne; Hizli) reported mean changes of −4.4, −4.4, and −6.1 points for the Serenoa repens arm, respectively. If we discount the two smallest trials (Gerber, N = 79; Hizli, N = 40) with short follow up periods (6 months, respectively), that leaves two large, adequately powered trials, each with 12-month follow ups. Bent shows no clinical efficacy; Debruyne does, but suffers from lack of a placebo arm. At this point we are inclined to accept the evidence of the placebo-controlled Bent trial.

Comparing Serenoa repens to placebo in a meta-analysis of peak urine flow at endpoint (Figure 1), ten trials reported an intergroup WMD of 1.02 mL/s (95% CI −0.14 to 2.19, P = 0.07), an nonsignificant difference and with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 30%). In a sensitivity analysis including only the four largest, higher quality trials (Bent; Braeckman; Descotes; Willetts), the WMD was 0.43 points (95% CI −0.35 to 1.21, P > 0.05), a non-significant difference with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). A second meta-analysis comparing mean change also found no significant difference (WMD 0.31, 95% CI −0.56 to 1.17, P > 0.05; 2 trials).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Serenoa repens versus placebo, outcome: 1.4 Peak urine flow (mL/s) at endpoint.

In Bent’s high quality trial comparing ’serious adverse events,’ the relative risk (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.99, P = 0.05) of a serious event was greater for the placebo arm than the Serenoa repens arm. In a meta-analysis of the relative risk of ’any adverse event’, there was no significant difference between Serenoa repens and placebo (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.51, P > 0.05; 5 trials).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall completeness of the evidence was fairly good in 2008, and much better than it was at the inauguration of this review in 1998. For example, of the 14 trials that were placebo controlled and compared to Serenoa repens monotherapy, 7 utilized the commercialized Permixon®, which assured that the comparators were equivalent. Fifteen of the thirty trials used a validated score - the AUA or IPSS - to assess symptoms. Fourteen of fifteen of those trials provided baseline and endpoint IPSS or AUA scores, although not all gave SD. Nine of the fifteen reporting studies provided mean change with SD for either the IPSS or AUA total score. Of 14 trials with baseline and endpoint data for nocturia, 11 provided means, 1 provided “per cent with nocturia,” and 1 an AUA nocturia grade. Twenty-one trials reported baseline and endpoint data for peak urine flow, and five reported mean differences. Ten of thirty trials provided data at baseline and endpoint for prostate size, and three provided mean change with SD.

In general, the newest trials reported validated symptom scores, provided baseline and endpoint data (with SD, SEM (standard errors), CI) and mean differences. In the future, larger, high quality trials, (and a placebo arm in trials with controls), using validated symptom-scale scores and mean changes for outcome measures, will give us much better data to judge the efficacy of Serenoa repens.

Quality of the evidence

Our first iteration of this review included 18 trials, of which only 6 randomized 100 subjects or more. The other 12 trials ranged from 22 to 80 subjects. In our update of 2002 we added three trials, with subjects of 44, 85, and 101, respectively. This update has added nine trials enrolling subjects ranging from 60 to 704. Of 30 trials, 14 randomized 100 subjects or more (range 100 to 1098). This trend of higher powered trials - and with their corresponding smaller CI - yields statistically better evidence. There has been upward trends in the quality of studies and evidence. As noted above, 15 of 30 (50%) trials used validated symptom-scale scores; in the 1998 review only 3 of 18 (17%) did. Eleven trials reported nocturia data (times/per evening) at baseline and endpoint, but none reported mean change with SD, a statistically better metric, because repeated measures at baseline and endpoint tend to be correlated, leading to smaller SEM and CI, and thus a truer estimate of treatment effect. For prostate size and peak urine flow, there was more data reporting mean change. Four trials reported baselines and endpoints for prostate size, and three reported mean changes. For peak urine flow, the ratio was more lopsided: 13 trials reported baselines and endpoints, and 5 reported mean changes.

Potential biases in the review process

From our very first review in 1998 we were sensitive to biases among trials and their reported outcomes. We decided a priori to report all outcomes using a random-effects model, which is a more conservative estimate of treatment effect. In the 10 years we began this process, there has been a dismaying lack of clarity of descriptions, or even descriptions, of study design, even among top-drawer, peer-reviewed journals. We evaluated five criteria

adequate sequence generation (was there an articulated rule for allocating interventions based on chance?)

allocation concealment (was there any foreknowledge of the allocation of interventions by anyone?)

blinding (during the course of the trial were study participants and personnel blinded to the knowledge of who received which intervention?)

incomplete outcome data addressed (did the trial assess all patients, or account for those not assessed?)

free of other bias (selective outcome reporting, differences between/among arms in how outcomes were determined), and graded them by A (“yes”), B (“unclear”), and C (“no”). For “adequate sequence generation” among the 30 included studies, we reported 30% with “adequate” scores (the other 20 trials scored “unclear”). “Allocation concealment” was “adequate” in 43% (13/30). The other 17 trials reported “unclear” (57%). Eighty-seven per cent of the trials reported “adequate” blinding. Two trials (7%) were “unclear,” and 2 (7%) were not blinded. Twenty-five of thirty trials (83%) reported no “incomplete outcome data.” Ninety-seven per cent reported no “selective [outcome] reporting,” and 93% reported no other sources of bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In this update we report that Serenoa repens monotherapy does not improve urinary symptom scores (IPSS, AUA), peak urine flow, or shrink the prostate. In general, these results contradict our two previous findings in 1998 and 2002, as well as - in part - a systematic review performed in 2004 (Boyle 2004). In this analysis Boyle compared Permixon® to placebo with 14 RCTs and three open-label trials for a total of 4280 subjects. Comparing IPSS total scores, Boyle noted an intra group point decrease for both arms (Permixon® 4.78 versus placebo 4.54), but based on only one and two studies, respectively. In the head-to-head comparison, the intergroup difference was not significant (−1.10 points (95% CI −1.66 to 1.46, P > 0.05). In our two-study meta-analysis we found no difference in mean change (−0.77 (95% CI −2.88 to 1.34, P > 0.05), but also with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 63%). These analyses would suggest that there is no benefit to Serenoa repens over placebo.

In Boyle, both arms increased peak urine flow (Permixon® 1.02 mL/s versus placebo 1.20 mL/s) from baseline, but the comparison favored placebo (P = 0.04). In our meta-analysis (10 trials) of endpoints and with minimal heterogeneity (I2 = 30%), there was no significant difference among trials (WMD 1.02 mL/s, 95% CI −0.14 to 2.19, P = 0.08). Comparing mean change (2 trials), our meta-analysis found no significant difference as well (0.31 mL/s (95% CI −0.56 to 1.17, P > 0.05) and no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Boyle also noted a significant decrease in nocturnal voids for both arms (Permixon® 0.38 versus placebo 0.63), with the comparison favoring placebo (P < 0.05). In our meta-analysis (Analysis 1.3) of nocturia at endpoint, there was a significant difference (−0.78 nocturnal voids, 95% CI −1.34 to −0.22, P < 0.05) between arms favoring Serenoa repens, but also with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 66%).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Serenoa repens is widely used for symptomatic BPH in Europe and the United States, and widely recommended by clinicians in both. Millions of men use it, with little or no evidence of its efficacy or safety. We now have some evidence of both, and the evidence points to a safe product (at current doses) but with little or no efficacy. For both Europe and the US, greater government regulation is needed. Europe, at a national or transnational level, needs to insure that phytotherapeutic agents, such as Serenoa repens, are safe and live up to their scientific claims. In the US the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) needs to revisit the 1994 Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act, which holds herbal remedies to a ’no standard’ compared to pharmaceutical agents. If herbal products make scientific claims, they need to support those claims with scientific evidence that is open to public scrutiny.

Implications for research

In this update we report the efficacy of Serenoa repens is in doubt. Although we acknowledge a certain amount of ambiguity in the evidence, we believe that as future trials of the quality of Bent’s are published, the inefficacy of Serenoa repens will become clearer. These future trials will need to be adequately powered, use validated symptom scores, and be properly randomized and blinded. If Serenoa repens is compared to other interventions, a placebo arm should also be added.

Serenoa repens and other phytotherapies for BPH should be scrutinized and subjected to trials just as are all regulated drugs. For too long these and other homeopathic phytotherapies have been used as accepted remedies without the proper skepticism they deserve. This practice should become a thing of the past.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by Grant Number R24 AT001293 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant Number 1R01 DK063300-01A2. Authors are employees of the US Department of Veterans Affairs. The contents of this systematic review are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs. We also wish to thank Maurizio Tiso, Margaret Haugh, Rich Crawford, Tatyana Shamilyan, Philipp Dahm, and Joan Barnes for their work in translating and abstracting data from the non-English language studies.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Management Decision and Research Center-Department of Veterans Affairs HSRD, USA.

Minneapolis/VISN-13 Center for Chronic Diseases Outcomes Research (CCDOR), USA.

External sources

-

The Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field bursary award, USA.

The Cochrane review group Prostatic Diseases and Urologic Cancers received a one-time payment from the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field to update this review.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Number of sites unknown Randomization: unclear Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Germany/Italy Study setting: community N = 101 Baseline IPSS: Sabal extract 9.6, Placebo 8.9 Baseline prostate volume: Sabal extract 34.5 cc, Placebo 31.7 cc Mean age: 66.1 Age range: NA Race: White Diagnostic criteria: confirmed diagnosis of BPH with enlargement of the prostate, symptoms of obstruction and a maximum flow of < 15 mL/s |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Sabal extract (LG166/S) 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 6 months Lost to follow up: 3(?) |

|

| Outcomes | IPSS symptom score Peak urine flow Prostate volume Sexual function Dropouts due to side effects: 0 |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: patients treated for BPH within 1 month of the trial start; prostate cancer; acute urinary tract infection; chronic prostatitis; neurogenic bladder | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | B - per protocol outcomes |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Dual-site and surrounding community Randomization: computer generated Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Northern California Study setting: VA Hospital/Kaiser Permanente and community N = 225 Baseline AUA: SR 15.7, Placebo 15.0 Baseline prostate volume: SR 34.7 cc, Placebo 33.9 cc Mean age: 63.0 Age range: NA Race: White 82%; Black 5%; Asian or Pacific Islander 7%; Hispanic 5%; Other 1% Diagnostic criteria: moderate-to-severe symptoms of BPH (AUA ≧ 8); QMAX < 15 mL/s |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Sabal extract 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 12 months Lost to follow up: n = 9 |

|

| Outcomes | AUA symptom score BPH Impact Index Peak urine flow |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: < 49 years old; less than moderate symptoms of BPH (AUA < 8); Qmax < 4 mL/s or residual volume > 250 mL after voiding; hx of prostate cancer; surgery for BPH; urethral stricture; neurogenic bladder; creatinine > 2 mg/dL; PSA > 4 ng/dL; medications known to affect urination; severe concomitant disease | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A -Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Single-site study Randomization: Sealed envelopes Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Italy Study setting: community N = 22 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 68.0 Age range: 54 to 78 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Men with symptomatic BPH not in need of surgery |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Permixon® 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 8.5 weeks Lost to follow up: None |

|

| Outcomes | Dysuria (4-point scale) Peak urine flow Mean urine flow Voiding time Total voided volume Pollachiuria Dropouts due to side effects: not reported |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Cancer; currently on other medication; urinary tract infection | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | B |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Number of sites unknown Randomization: sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Belgium Study setting: community N = 238 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: Prostaserene™ 44 cc, Placebo 45 cc Mean age: 65 Age range: 57 to 73 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Peak urine flow 5 to 15 mL/s; residual urine volume less/equal 60 mL; Personal score list 0 to 4; No global physician assessment |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Prostaserene® 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 12 weeks Lost to follow up: 5% |

|

| Outcomes | Symptom improvement Peak urine flow Mean urine flow Total voided volume Bladder residual volume Prostate size Dropouts due to side effects: < 1% |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Age > 80 years; prostate/other cancers; urine flow < 5mls/sec or > 15mls/sec; residual volume > 60 mL; currently on medications; urinary tract infection | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B - Randomization by each center |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Per protocol analysis |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: random allocation according to a centrally controlled code list Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Sweden and Denmark Study setting: community N = 55 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 61.6 Age range: 51 to 72 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: The presence of BPH on the basis of history, clinical examination of the prostate and acid phosphatase determination |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Combination phytotherapy: Curbicin (Sabal serrulata 80 mg and Cucurbita pepo L. (pumpkin seeds) 80 mg) 2 tablets thrice daily Study duration: 12 weeks Lost to follow up: 4% |

|

| Outcomes | Dysuria Mean urine flow Voiding time Bladder residual volume Nocturia Patient self-evaluation Dropouts due to side effects: 0 |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Need of imminent surgery due to symptom severity; bladder residual urine > 300 mL; previous treatment with Curbicin | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: computer-generated randomization code Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Nine European countries Study setting: community N = 1098 Baseline IPSS: Permixon® 15.7, Finasteride 15.7 Baseline prostate volume: Permixon® 43.0 cc, Finasteride 44.0 cc Mean age: 64.5 Age range: 49 to 88 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: BPH diagnosed by digital rectal exam (DRE); International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) > 6; Maximun urinary flow between 4 to 15mL/sec (with a urine volume at least 150 mL, and a postvoid residue of < 200 mL); prostate size > 25mL; serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) < 10 ng/mL (prostates less than or equal to 60 mL) or 15 ng/mL (prostates > 60 mL); good mental and physical condition |

|

| Interventions | Control: finasteride 5 mg (Proscar) plus placebo (morning) and two placebos (evening) Treatment: Permixon® 160 mg plus placebo twice daily Study duration: 26 weeks Lost to follow up: 13.4% |

|

| Outcomes | Symptom improvement - IPSS symptom score (0 to 35 points) Quality of life score (0 to 6 points) Sexual function score (0 to 20 points) Peak urine flow Mean urine flow Total voided volume Bladder residual volume Prostate size (volume) Serum PSA Dropouts due to side effects: 4% (28 Permixon® and 14 finasteride) |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Prostate cancer; bladder disease; abnormal liver function; diuretics or drugs with antiandrogenic or alpha-receptor properties in the preceding 3 months; urogenital infections; disease potentially affecting micturition | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Number of sites unknown Randomization: unclear Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: France Study setting: community N = 110 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate size: NA Mean age: NA Age range: NA Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Peak urine flow; mean urine flow; residual urine volume; (No details given) |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Permixon® 80 mg twice daily Average follow up: 4 weeks Lost to follow up: 15% |

|

| Outcomes | Dysuria Mean urine flow Bladder residual volume Nocturia Patient self-rating Physician self-rating Dropouts due to side effects: not reported |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: prostate cancer | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | B - Per protocol analysis |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: numbered or coded identical containers administered sequentially Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: France Study setting: community N = 168 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 69 Age range: NA Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Patients with “prostatism” or for whom surgery was not indicated (no mechanical or infectious complications) |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Permixon® 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 10 weeks Lost to follow up: 13% |

|

| Outcomes | Symptom score (# of daily mictions) Dysuria (4-point scale) Bladder residual volume Nocturia Dropouts due to side effects: not reported |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Symptoms for at least 6 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | B - Per protocol analysis |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: not described Patients blinded; providers blinded but not described |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: 98 centers in 11 European countries Study setting: community N = 704 Baseline IPSS: Permixon® 15.5, Tamsulosin 15.2 Baseline prostate size: Permixon® 48.0 cc, Tamsulosin 47.7 cc Mean age: 64.9 Age range: 50 to 85 Race: NA Diagnostic criteria: IPSS ≥ 10; Peak urine flow 5 to 15 mL/s; voided vol at least 150 mL; post-voiding vol < 150 mL; prostate vol ≥ 25 cc; serum PSA < 4 ng/mL (men w/PSA 4 to 10 ng/mL required a free/total PSA ratio of at least 15%) |

|

| Interventions | Control: tamsulosin 0.4 ng daily (capsules were matched in color, smell, size) Treatment: Permixon® 320 ng daily Follow up: 12 months Lost to follow up: n = 110 |

|

| Outcomes | IPSS total score Nocturia Peak urine flow Dropouts due to side effects: tamsulosin n = 8; Permixon® n = 3 |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: hx of bladder disease likely to affect micturition; urethral stenosis; PC; pelvic radiotherapy; repeated infection of the urinary tract; chronic bacterial prostatitis; any disease likely to cause urinary problems; pts w/clinically significant cardiovascular dx; hematuria, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; hx severe hepatic failure; abnormal liver function tests; concomitant medication likely to interfere w/study medication; known hypersensitivity to study drugs; participation in other clinical trial in previous 3 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | B |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization:noted but method not stated Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: France Study setting: community N = 215 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 66.3 Age range: NA Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Mild-moderate (stage I or II) BPH; Dysuria: daytime and nocturnal urinary frequency (> 2 nocturnal micturitions, excluding those at bedtime and on awakening) of at least 8 weeks; maximum urinary flow > or equal to 5 mL/s |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Permixon® 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 4 weeks Lost to follow up: 18% |

|

| Outcomes | Dysuria Peak urine flow Mean change in daytime urinary frequency Nocturia Patient-based global efficacy Physician-based global efficacy Dropouts due to side effects: 1 (complaints of fatigue, depression and stomach upset) |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Excessively mild or severe symptoms of BPH including incontinence, bladder distension, urine flow< 5mls/sec; cancer; prior treatment for BPH; urogenital infection; hematuria; diabetes; any prior surgery that could induce dysuria | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Single-site study Randomization: noted but method not stated Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Italy Study setting: community N = 30 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: NA Age range: 44 to 78 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: Men with manageable BPH |

|

| Interventions | Control: matching placebo Treatment: Permixon® 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 4 weeks Lost to follow up: none |

|

| Outcomes | Peak urine flow Mean urine flow Bladder residual volume Prostate size (qualitative scale used) Nocturia Dropouts due to side effects: none |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Prior treatment for BPH | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: noted but not described Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Germany Study setting: private out-patient centers N = 140 Baseline IPSS: Prostagutt® forte 20.0, Tamsulosin 21.0 Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 65.0 Age range: NA Race: NA Diagnostic criteria: maximum urinary flow rate ≤ 12 mL/s at a urinary volume ≥ 150 mL |

|

| Interventions | Control: tamsulosin 0.4 mg daily Treatment: Prostagutt® forte (sabal fruit extract+urtica root extract) twice daily Study duration: 60 weeks Lost to follow up: n = 3 (a total of 121 completed the trial at week 60) |

|

| Outcomes | IPSS total score IPSS QoL CEDQ (Cologne Erectile Dysfunction Questionnaire) Peak urine flow Mean urine flow Mean urine volume Duration of flow increase Ultrasound residual volume |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Pts whose peak urinary volume changed by more than 3 mL/s during a 2-week period; < 50 yrs old; IPSS < 13 and < 3 for the IPSS QoL; residual urinary volume < 150 mL; congested urinary tract passages; an indication of BPH surgery; urinary tract infection; prostate carcinoma; diabetes; neurogenic or bladder dysfunction; previous treatment w/5ARI; concomitant medication that could interfere w/treatment efficacy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization: unclear Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Croatia Study setting: community N = 30 Baseline IPSS: NA Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 65.0 Age range: 40 to 82 Race: White Diagnostic criteria: BPH, stage I–II (Vahlensieck) |

|

| Interventions | Control: placebo Treatment: Prostagutt® forte (Serenoa repens and Urtica dioica) 20 drops thrice daily Study duration: 6 weeks Lost to follow up: none |

|

| Outcomes | Physician rating of improvement Peak urine flow Bladder residual volume Dropouts due to side effects: none |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: Stage IV prostate adenoma; bacterial prostatitis; cystitis; urethritis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | B |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite or single-site: NA Randomization: computer number table Patients blinded; providers blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: USA Study setting: community N = 85 Baseline IPSS: Serenoa repens 16.7, Placebo 15.8 Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 65.0 Age range: ≥ 45 Race: NA Diagnostic criteria: IPSS score ≥ 8 |

|

| Interventions | Control: placebo Treatment: Serenoa repens 160 mg twice daily Study duration: 6 months Lost to follow up: 7% (2 Serenoa repens, 4 Placebo) |

|

| Outcomes | Symptom improvement - IPSS symptom score Quality of Life score Peak urine flow Dropouts due to side effects: 1% (n = 1, Serenoa repens) |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: prostate surgery; history of prostate cancer or urethral stricture; treated with finasteride, saw palmetto or other alternative therapy (past 6 months); or treated with alpha-blocker (within 1 month) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Multisite study Randomization noted but not described Patients and providers blinded; unsure if assessors blinded |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: France Study setting: 47 regional settings N = 329 Baseline IPSS: tamsulosin + Serenoa repens (Permixon®) 16.2, Tamsulosin 16.3 Baseline prostate volume: NA Mean age: 65.0 Age range: NA Race: NA Diagnostic criteria: IPSS ≥ 13, Peak urine flow 7 to 15 mL/s |

|

| Interventions | Control: tamsulosin daily + placebo twice daily Treatment: tamsulosin daily + Serenoa repens (Permixon®) twice daily Study duration: 52 weeks Lost to follow up: n = 64 |

|

| Outcomes | Symptom improvement-IPSS total score IPSS QoL & UROLIFE© BPH QoL9 Peak urine flow Dropouts due to side effects: none |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: previous surgery on the prostate, vesicle collar or pelvic area; residual post-urine volume of >300 mL; prostate cancer; urine infection; α/β-blockers, α-agonists, cholinergics or anticholinergics were prohibited; hepatic insufficiency; cardiovascular event or cerebrovascular event; allergy to intervention drugs Treatments for BPH (such as α-blockers) stopped at least 15 days before randomization; other treatments, such as plant extracts and finasteride, were stopped 1 month before randomization. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | B |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | B |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of selective reporting? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Free of other bias? | Yes | A - Adequate |

| Methods | Single or multisite: NA Randomization: NA Blinding: not described |

|

| Participants | Geographic region: Turkey Study setting: unknown N = 60 Baseline IPSS: Serenoa repens (Permixon®) 16.2, tamsulosin 18.0, Serenoa repens (Permixon®) + tamsulosin 15.6 Baseline prostate volume: Serenoa repens (Permixon®) 35.2 cc, tamsulosin 38.6 cc, Serenoa repens (Permixon®) + tamsulosin 31.2 cc Mean age: 58.6 Age range: 43 to 73 Race: NA Diagnostic criteria: IPSS ≥ 10; Peak urine flow 5 to 15 mL; prostate volume ≥ 25 cc; PSA ≤ 4 ng/mL |

|

| Interventions | Control 1: tamsulosin 0.4 mg daily Control 2: Serenoa repens (Permixon®) 320 mg daily + tamsulosin 0.4 mg daily Treatment: Serenoa repens (Permixon®) 320 mg daily Study duration: 24 weeks Lost to follow up: none |

|

| Outcomes | IPSS total score IPSS QoL Prostate volume PSA Post-void residual volume |

|

| Notes | Exclusions: cardiovascular disease; hematuria; insulin dependent diabetes; prostate cancer; concomitant meds likely to interfere w/study meds; hypersensitivity to study drugs; concomitant meds likely to interfere w/study meds; hypersensitivity to study drugs; pelvic radiotherapy; UT repeated infection; chronic bacterial prostatitis; any other disease that causes urinary problems; hx of severe hepatic failure; abnormal liver function; hx of bladder disease likely to affect micturition; urethral stenosis; and participating in clinical trial in last 3 months. | |

| Risk of bias | ||