Abstract

Induction and activation of nitric oxide (NO) synthases (NOS) and excessive production of NO are common features of almost all diseases associated with infection and acute or chronic inflammation, although the contribution of NO to the pathophysiology of these diseases is highly multifactorial and often still a matter of controversy. Because of its direct impact on tissue oxygenation and cellular oxygen (O2) consumption and redistribution, the ability of NO to regulate various aspects of hypoxia-induced signaling has received widespread attention. Conditions of tissue hypoxia and the activation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) have been implicated in hypoxia or in cancer biology, but are also being increasingly recognized as important features of acute and chronic inflammation. Thus, the activation of HIF transcription factors has been increasingly implicated in inflammatory diseases, and recent studies have indicated its critical importance in regulating phagocyte function, inflammatory mediator production, and regulation of epithelial integrity and repair processes. Finally, HIF also appears to contribute to important features of tissue fibrosis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, processes that are associated with tissue remodeling in various non-malignant chronic inflammatory disorders. In this review, we briefly summarize the current state of knowledge with respect to the general mechanisms involved in HIF regulation and the impact of NO on HIF activation. Secondly, we will summarize the major recent findings demonstrating a role for HIF signaling in infection, inflammation, and tissue repair and remodeling, and will address the involvement of NO. The growing interest in hypoxia-induced signaling and its relation with NO biology is expected to lead to further insights into the complex roles of NO in acute or chronic inflammatory diseases and may point to the importance of HIF signaling as key feature of NO-mediated events during these disorders.

Hypoxia, Oxygen Sensing and Inflammation

Dramatic changes in metabolism including increased generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), depletion of local nutrients, and an increased demand for oxygen (O2) are characteristic features of the inflammatory response [1]. Increased metabolic activity in inflamed tissue results, in part, from the recruitment of myeloid cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, to inflammatory lesions and their subsequent involvement in phagocytosis and inflammatory mediator release [2]. These processes, coupled with decreased perfusion due to microvascular injury, increased interstitial pressure, or altered hemostasis, all contribute to an imbalance between O2 supply and demand creating a hypoxic (decreased O2 availability) microenvironment at foci of tissue inflammation. In healthy non-pulmonary tissues, the O2 tension (pO2) generally ranges between 20 and 70 mm Hg (i.e., 2.5–9% O2), whereas O2 tensions often drop to <10 mm Hg (>1% O2) in diseased tissues [3,4]. Thus, tissue hypoxia is a hallmark feature of several inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and colitis.

The depletion of available O2 needs to be sensed by cells resident in the hypoxic environment in order to elicit appropriate changes that are necessary to adapt to and circumvent the O2 deficit. Oxygen sensing is carried out through the activation of oxygen-dependent transcription factors that induce response programs directed towards increasing O2 supply and promoting shifts towards anaerobic metabolism. In this way, hypoxia itself can significantly contribute to the inflammatory response through the induction of genes involved in angiogenesis and vascular permeability. These transcriptional response programs are primarily mediated by hypoxia inducible factors 1, 2 and 3 (HIF-1,-2,-3) as master regulator of O2 homeostasis [5]. In the context of pathophysiology, it is well appreciated that the adaptive responses elicited by HIF transcriptional programs are utilized by tumor cells to promote the advancement of several stages of cancer progression. Increased HIF-1 (the most studied isoform) levels are typically associated with decreased patient prognosis, and several therapeutics targeting HIF-1 have been identified and validated as anticancer agents [6,7]. In addition to the well-appreciated role of HIF-1 in tumor biology [6,8,9], activation of HIF in non-malignant inflammatory diseases is becoming increasingly appreciated, and a number of recent studies have demonstrated that HIFs coordinate several functions of the innate immune and inflammatory response [3]. Indeed, accumulating evidence implicates the presence and activation of HIF-1 signaling in a variety of inflammatory diseases, such as asthma [10], rheumatoid arthritis [11], atherosclerosis [12] chronic kidney disease [13] and inflammatory bowel disease [14]. However the consequences of HIF activation within the context of these disease states and their progression remain largely unknown, which forms the subject of active current and future research.

As outlined in a number of recent reviews (e.g. [15,16]), increased synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) by induction and activation of nitric oxide synthases (NOS) is a common hallmark of inflammatory diseases and NO acts as a versatile mediator of several aspects of inflammatory-immune responses. Because of its considerable similarities with O2, NO is also capable of interfering with O2 distribution and sensing mechanisms, as well as down-stream signaling mechanisms involving HIF, and the biological impact of enhanced NO production in inflammatory disease could therefore be largely mediated by its impact on tissue hypoxia and oxygen sensing mechanisms such as HIF. It is the purpose of this review to discuss the current knowledge regarding the functional importance of HIF-mediated pathways in various aspects of inflammation, and the mechanisms by which NO is able to interfere with these processes.

Mechanisms of HIF regulation and activation

Originally discovered in the context of induction of the erythropoietin gene under hypoxic conditions [17], HIF-1 has emerged to play central roles in response to several micro-environmental stresses in addition to hypoxia, including exposure to infectious pathogens, inflammatory cytokines, and NO and its metabolites [3,18-20]. Through transcriptional regulation of more than 100 genes, HIF-1 activation influences a diverse range of cell signaling pathways that are involved in glycolysis, erythropoiesis, angiogensis, pH regulation, myeloid cell function, epithelial barrier integrity, cell differentiation and apoptosis, that can contribute to both homeostasis and pathophysiology [21,22]. In the following sections, we will briefly summarize the major biochemical mechanisms involved in regulation of HIF-1, which comprise both oxygen-dependent regulation of HIF stability and transcriptional and post-translational regulation of HIF expression and activation.

Hypoxic regulation of HIF

HIF is a heterodimeric transcription factor that is regulated primarily at the level of its alpha subunit, of which there are three known isoforms (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α). While the beta subunit, HIF-1β (also known as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator; ARNT), appears to constitutively expressed and resides in the nucleus, the HIF-α subunits are oxygen sensitive and highly short-lived during normoxic conditions. In the presence of O2, prolyl hydroxylase enzymes (PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3) catalyze the iron-dependent hydroxylation of proline residues 402 and 564 in the oxygen dependent degradation domain (ODD) of HIF-1α [23,24]. This facilitates hydrogen bonding with the von Hippel Lindau protein (pVHL) which promotes HIF-1α polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome [25]. In addition, HIF-1α is also subject to hydroxylation on asparagine 804 at the C terminal domain by the asparaginyl hydroxylase, factor inhibiting HIF (FIH), which inhibits its binding to the transcriptional co-activator p300-CREB-binding protein (p300/CBP) [26,27]. Thus, both PHDs and FIH act as O2 sensors to minimize the stability and activity of HIF-1α. During conditions of hypoxia, PHD and FIH activity are attenuated allowing for the stabilization, nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of HIF-1α, which involves dimerization with HIF-1β and binding to pentanucleotide hypoxic response element (HRE) sequences within the promoter regions of a variety of hypoxia-sensitive genes to regulate their expression.

Using in vitro culture systems, activation of HIF-1 was found to be half maximal under 1.5 - 2% O2 (10-15 mm Hg) atmosphere [28]. However, because of the relatively slow diffusion of O2 through cell culture media, which may require as long as 30 min for a change in headspace O2 levels to be effective at the cell surface [29], and the variability in cell culture systems and experimental design by various groups studying HIF signaling, direct associations between exposure O2 levels and various aspects of HIF signaling cannot always be made. Also, the extent of HIF activation is often greater during conditions of intermittent hypoxia rather than chronic hypoxia [5,30] suggesting that HIF activation is controlled by dynamic changes in O2 rather than by persistent low O2 levels.

Transcriptional regulation of HIF-1

In addition to hydroxylation by PHDs and FIH, HIF-α subunit levels and activity are regulated by other transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms [18,31], and, as will be discussed below, several of these mechanisms can be directly influenced by NO or related RNS. Various inflammatory cytokines or growth factors have been found to induce HIF-1α mRNA synthesis by transcriptional activation, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), protein kinase C (PKC) and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) signaling pathways were implicated as being upstream effectors in these processes [32-35]. In addition, the basal expression of HIF-1α mRNA has been linked to the activation of specific protein 1 (SP1) and NF-κB [36,37]. HIF-1α protein synthesis is also regulated at the level of translation by various inflammatory mediators and growth factors, through interaction with their cognate receptor tyrosine kinase, leading to activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and downstream activation of the serine/threonine kinases AKT (also known as protein kinase B) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). These pathways subsequently regulate ribosomal S6 protein and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF-4E) to increase translation of a subset of mRNAs (including HIF-1α mRNA) into protein [9,38]. Several pro-inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α and IL-1β [39], adenosine [40], as well as NO [41,42], have been reported to induce HIF-1α protein expression via this mechanism [33,39,41,42]. Additional post-transcriptional mechanisms of HIF-1α regulation have recently been reviewed [43]and will not be further discussed here.

Interrelation between HIF-1 and NF-κB pathways

Because of the central role of the transcription factor NF-κB in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses and inflammation [44], considerable attention has been give to potential interactions between NF-κB and HIF-1 signaling pathways. A number of studies have indicated that hypoxia enhances NF-κB activity, primarily through affecting the canonical pathway [45]. Because PHD1 and PHD2 appear to act to repress the canonical NF-κB pathway by direct hydroxylation of inhibitory kappa B kinase β (IKK-β), and p105 (a precursor of p50) and inhibitory kappa B α (IκBα) are subject to hydroxylation by FIH, hydroxylase inhibition during hypoxia is expected to impact directly upon NF-κB. Moreover, several recent studies have indicated that both hypoxia and exposure to bacterial LPS induce HIF-1α mRNA expression in an NF-κB dependent manner [31,46]. Elegant studies using mice deficient in IKK-β, the upstream activator of canonical NF-κB signaling, demonstrated that activation of NF-κB is essential for accumulation of HIF-1α protein in response to both gram positive and gram negative bacterial infection as well as hypoxia [37]. In addition, HIF-1α mRNA was markedly down-regulated in IKK-β deficient cells, suggesting that basal activation of NF-κB is required for induction of HIF-1α mRNA [37]. Conversely, HIF-1 has also been shown to mediate NF-κB activation in neutrophils during anoxia [47] and contribute to macrophage production of NF-κB regulated cytokines upon treatment with LPS [48], illustrating a intimate relationship between HIF-1 and NF-κB pathways in cellular adaption to hypoxia and in regulation of innate immune responses [3,37,47].

Post-translational regulation of HIF activation

In addition to post-translational proline or asparagine hydroxylation within HIF-1α, other post-translational mechanisms have been identified in regulation of HIF-1α activity and turnover. Phosphorylation of HIF-1α on serine residues 641 and 643 of HIF-1α by p42/p44 MAPK is critical in promoting its nuclear translocation and HIF-1 transcriptional activity [49,50]. In its unphosphorylated form, HIF-1α binding to HIF-1β is largely diminished, and HIF-1α can bind to murine double minute (Mdm2) (or its human homologue Hdm2), a negative regulator of p53, and promote p53 accumulation and nuclear transport [51,52]. In this way, dephosphorylated HIF-1α was the predominant form found to regulate p53-mediated apoptosis induced by hypoxia in breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells [52]. Additional phosphorylation of HIF-1α by glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) actually leads to HIF destabilization, independent of the VHL pathway [53], and HIF transcriptional activity is also subject to regulation by acetylation [54] and SUMOylation [55,56]. More important in the context of the present review are reports showing that HIF-1α or other proteins in the HIF signaling pathway are subject to S-nitrosylation on critical cysteine residues [57] (see also next sections). Other reports indicate that the cellular GSH/GSSG ratio is an important determinant for the induction of HIF [58-60], suggesting a role for cysteine oxidation in HIF regulation. Several studies have shown induction of HIF by oxidants [61] or by cellular electrophiles such as 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin-J2 (15d-PGJ2) or acrolein [62], but the specific oxidative or electrophilic modifications were not identified, and HIF regulation in these cases may relate to dysregulation of cellular redox systems such as thioredoxin [63].

Given their pleiotropic effects on diverse cellular signaling pathways [15,16,64], NO and related RNS such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−) or S-nitrosothiols (RSNO) have the ability to affect HIF-1 activation at both direct and indirect levels. The activation of both NF-κB and HIF-1 leads to the induction of inducible NO synthase (iNOS; NOS2) in several cell types [65,66], and NOS2-derived NO might in turn regulate these transcription factors in a feedback mechanism. Indeed, an inhibitory feedback mechanism has been described for NF-κB which involves S-nitrosylation of key components within this signaling pathway [67-69], although NO and ONOO− can also positively regulate NF-κB by several mechanisms [15]. As will be discussed in the next section, various mechanisms of positive and negative regulation of HIF signaling by NO have been described.

Regulation of HIF-1 signaling by NO

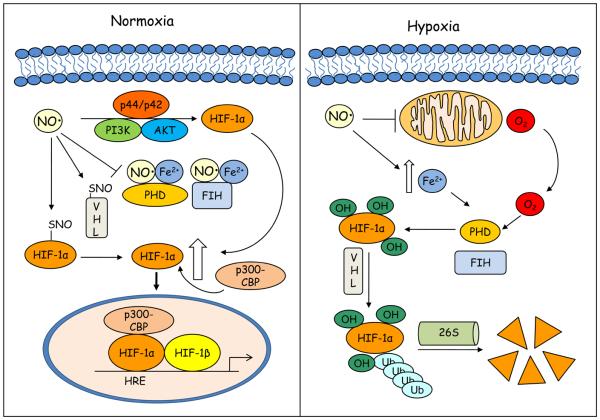

Because of its many influences on cell signaling, NO can affect HIF-1 activation at multiple levels via numerous mechanisms [20], and much of our current knowledge is based on studies of HIF-1 related signaling in the presence of pharmacological NO-donor compounds. These various studies have indicated that these regulatory capacities of NO are highly complex, and depend of local NO concentration, variable effects of different NO metabolites or bioactive forms, and O2 availability. For example, while low concentrations of NO (< 400 nM) have been reported to facilitate HIF-1α degradation and impair HIF-1 signaling, high concentrations (>1 μM) [70] of NO are capable of stabilizing HIF-1α during normoxia, thus mimicking a hypoxia response. Given the complex nature of HIF regulation, which involves many diverse transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms, it would be impractical to exhaustively summarize all potential mechanisms by which NO or RNS can affect these various mechanisms. Therefore, we will restrict ourselves to discussing the major direct mechanisms by which NO or S-nitrosothiols such as S-nitroso-glutathione (GSNO) can regulate HIF-1 signaling in the following sections, which are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. For more detailed information, the reader is referred to several excellent, more comprehensive reviews [20,71,72].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the mechanisms by which NO impacts on HIF activation during normoxic or hypoxic conditions.

Under normoxia (left panel) NO can inhibit prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) and factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) activity by interacting with enzyme bound Fe2+, preventing hydroxylation of HIF-1α proline and asparagine residues that target HIF-1α for degradation and block interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300-CBP. NO can also increase HIF-1α expression through the activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways and stabilize HIF-1α by S-nitrosylation. S-nitrosylation of von Hippel Lindau (VHL) can also prevent HIF-1α ubiquitination and degradation. During hypoxic conditions (right panel), competitive binding of NO to mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase results in re-distribution of O2 to restore PHD activity. NO can also promote increases in intracellular free iron that enhance PHD activity. p300-CBP, p300-CREB-binding protein; FIH, factor inhibiting HIF; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1α; HRE; hypoxic response element, PHD, prolyl hydroxylase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; VHL, von Hippel Lindau.

Regulation of HIF-1α by NO during hypoxia

The primary site of cellular O2 consumption in mammals is cytochrome c oxidase (CcO), the terminal enzyme in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which is central to oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis [73]. NO can readily interact with CcO and thereby modulate its activity and O2 consumption. The ability of NO to compete with O2 for CcO binding is dependent on the redox state of CcO, local O2 concentrations, and NO concentrations [74]. During conditions of hypoxia, when O2 concentrations are low and CcO is reduced, competitive binding of NO inhibits CcO activity resulting in decreased consumption and redistribution of cellular O2 [74]. This would create a situation of “metabolic hypoxia” in which, despite available O2, its use in mitochondrial respiration is prevented by occupation of CcO by NO, leading to increased O2 availability for prolyl hydroxylation of HIF-1α, leading to a situation in which the cell may fail to register hypoxia [75,76]. Accordingly, a number of studies have shown that NO is capable of attenuating HIF-1α accumulation and DNA binding during hypoxia. This was primarily related to regained PHD activity in the presence of NO due to inhibition of O2 consumption by CcO and re-distribution of O2 [76]. Evidence providing support for this explanation have included the observation that inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration destabilize HIF-1α and by analysis of HIF-1α mutational constructs that lacked either the ODD domain or specifically, proline residues 402 and 564, which were both necessary for the NO-mediated destabilization of HIF-1 during hypoxia [76,77]. Additional experiments using a pVHL-HIF-1α binding assay showed increased PHD activity under hypoxia in the presence of NO compared to hypoxia alone [78]. In addition to enhancing PHD activity by O2 redistribution, NO may also promote PHD transcription during hypoxia, as shown by studies in which S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) was found to induce PHD2 and PHD3 mRNA and protein levels by a HIF-dependent mechanism [79,80].

Since the enzymatic activity of PHD not only requires O2, but also ferrous iron, ascorbate and 2-oxogluterate as cofactors [81], iron chelators such as desferrioxamine (DFX) are able to inhibit PHDs resulting in HIF-1α accumulation and increased transcriptional activity [82]. NO was found to antagonize DFX-elicited HIF-1α accumulation under normoxic conditions, which was attributed to increases in intracellular free iron [83]. Thus, NO can also inhibit HIF-1 activation during hypoxia by promoting cellular free iron and restoring PHD activity [83,84]. Calcium-induced activation of the protease calpain has been posed as another mechanism by which NO can destabilize HIF-1α during hypoxia [85].

Regulation of HIF-1 by NO during normoxia

In apparent contrast to the inhibitory actions of NO on HIF activation during hypoxia, a large number of studies have shown that exposure of multiple cell types to exogenous NO and S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) results in increased HIF-1α protein levels and HIF activity [86-89]. Likewise, over-expression of NOS2 using e.g. LLC-PK1 cells resulted in HIF-1α accumulation during normoxia [90]. Using a tetracycline-inducible system to conditionally induce NOS2 to varying degrees in HEK-293 cells, it was determined that HIF-1α accumulation and increased HIF-1 activity was observed when NO production was induced at rates of >1 μM, i.e. conditions that are likely to be encountered during inflammation [70]. Indeed, using a co-culture system, it was found that induction of NO synthesis by RAW 264.7 macrophages upon stimulation with LPS and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) was sufficient to promote HIF-1α accumulation in target LLC-PK1 cells [90]. Although the importance for NOS2 or other NOS isoforms with respect to HIF-1 activation in vivo has not been firmly established, several studies have demonstrated HIF-1α stabilization and activation in vivo by administration of S-nitrosothiols. Recent findings from our laboratory indicated that intratracheal administration of GSNO into mice resulted in increased lung HIF-1α protein levels and HIF-1 DNA binding activity [91]. Similarly, when mice, housed in normoxic conditions, were administered N-acetylcysteine (NAC; 10 mg/mL) in their drinking water for 3 weeks, this was converted to the stable NO transfer product S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine (SNOAC), which led to increased whole lung HIF-1 DNA binding activity [92].

The ability of NO to mimic hypoxic signaling suggests that NO and hypoxia may be employing overlapping mechanisms to stabilize HIF-1α, and a range of potential mechanisms have been proposed. NO-mediated HIF-1α protein induction was found to be independent of classical NO signaling via soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC)/cyclic GMP (cGMP) (sGC/cGMP) [93]. Since NO can readily interact with iron (II) in proteins [94], it is plausible that NO can inhibit PHDs by coordinating its non-heme Fe2+, but this has not been empirically proven. However, several studies have shown that GSNO can attenuate PHD activity [79,95]. GSNO decreased ubiquitination of HIF-1α in HEK293 cells and prevented interaction between HIF-1α and pVHL which was demonstrated to be a result of dose dependent inhibition of PHD activity [95]. While all three PHDs were found to be inhibited by GSNO in these studies, experiments targeting PHD2 and PHD3 with small interfering RNA (siRNA) revealed that reduced hydroxylation of HIF-1α by GSNO was achieved primarily by inhibition of PHD2 [79]. In fact, a biphasic response for NO with respect to HIF-1 regulation has been proposed, in which NO initially inhibits PHD activity leading to HIF-1α accumulation, which in turn results in increased PHD levels that prevent HIF-1α accumulation at later stages. Another S-nitrosothiol, S-nitroso-N-acetyl-penicillamine (SNAP), was also found to be capable of inhibiting FIH, resulting in enhanced HIF-1α C-terminal trans-activating domain (CTAD) activity [88].

Since these various studies indicate inhibition of HIF-1 hydroxylation and degradation primarily by S-nitrosothiols, rather than by NO itself, the mechanisms are most likely related to S-nitrosylation. Indeed, a number of studies have demonstrated the susceptibility of critical cysteine residues of several key proteins involved in HIF regulation, including HIF-1α itself, to S-nitrosylation, with functional consequences. Mutational constructs in 4T1 cells showed that the GSNO-mediated prevention of normoxic HIF-1α degradation was dependent on the S-nitrosylation of Cys533 [57] while treatment of COS-7 cells with the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) prevented HIF-1α accumulation by GSNO [86]. S-nitrosylation of Cys800 in HIF-1α has been associated with increased interaction with p300 and enhanced transcriptional activity [96]. Other lines of evidence implicate pVHL and p300/CBP as targets for S-nitrosylation, which may prevent HIF-1α ubiquitination or binding to p300/CBP, respectively [92,97]. Despite these observations, very little evidence exists to date regarding the significance of S-nitrosylation of HIF-1α or other proteins within the HIF-1 pathway in vivo. Intriguing recent studies by Lima et al. demonstrated increases in both total levels of HIF-1α protein and S-nitrosylated HIF-1α in myocardial tissue of normoxic mice that were genetically deficient in the GSNO metabolizing enzyme, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) [98].

It is becoming increasingly recognized that HIF pathways can be activated in the absence of hypoxia by various inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which promote HIF-1α gene expression and protein translation by activation of PI3K/Akt, MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Given their diverse biochemical properties, it is not surprising that NO or related RNS are involved in these activation mechanisms as well [18,31,99]. For example, GSNO-mediated HIF-1α protein accumulation and DNA binding in various cell types were found to correspond to phosphorylation/activation of Akt, and could be attenuated by inhibitors of PI3K [42,100]. Similarly, accumulation of HIF-1α protein and HIF-1-dependent gene expression induced by the NO-donor NOC18 was not due to effects on HIF-1α hydroxylation, ubiquitination, or degradation, but rather related to HIF-1α protein synthesis, presumably by nitrosative modification(s) of protein kinases including PI3K/Akt and MAPK and/or phosphatases such as PTEN [41,100]. Recently, Schleicher et al. demonstrated the importance of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) as an Akt1 substrate, illustrating additional associations between Akt and NOS in HIF-1 activation [99]. By generating Akt1-deficient mice (Akt1−/−) mice carrying eNOS knock-in mutations that rendered eNOS with constitutive or, significantly reduced, activity, these authors showed that constitutively active eNOS promoted HIF-1α stabilization and induction of HIF-1 target genes in an in vivo hind limb ischemia model and in primary endothelial cells exposed to 0.5% O2 in vitro, suggesting that Akt1 effects HIF-1α stability through the phosphorylation and activation of eNOS which subsequently increases NO production and inhibits PHD enzyme activity [99].

In aggregate, given the intricate relationship between NO and O2 homeostasis, it is not surprising that NO has a significant impact on hypoxia-sensing mechanisms and HIF-1 activation, but the overall effects of NO on HIF signaling are highly multifactorial and critically depend on localization and degree of NOS activation, as well as other factors such as O2 and redox status, which importantly affect NO biochemistry and metabolism. Another important fact to consider is that NO production by NOS2 in e.g. macrophages is also strongly dependent on O2 availability. Using an elegantly designed forced convection cell culture system that avoids the limitations of extracellular O2 diffusion and allows for rapid manipulation of cellular O2 tension, Otto and co-workers determined that macrophage NO production decreased with decreased O2 availability with an apparent KmO2 of 22 mm Hg [29]. This implies that biological NO production from NOS may vary widely within the range of biological pO2 (ranging from 20-70 mm Hg) and suggests that the ability NOS to affect HIF-1 activation is greater during relative normoxic conditions and may be markedly diminished during hypoxia. In the next section, we will discuss the current knowledge regarding the importance of HIF-1 activation during inflammatory diseases and its association with NO-mediated events.

Involvement of HIF in Inflammatory Diseases

While HIF-1 has been strongly implicated in tumorigenesis and malignant cancer progression [6,8,9], it is becoming increasingly apparent that HIF-1 activation is a feature of several non-malignant pathologies, and a growing body of literature demonstrates the presence of HIF-1α in diseased tissues of patients with several diverse inflammatory disorders. These findings are summarized in Table 1. pO2 tensions vary greatly within different tissues in both normal and diseased states. For example, within the kidney, O2 tensions are estimated at 5% (~38 mm Hg) in the renal cortex and ~1-2% O2 (8-15 mm Hg) in the renal medulla [13]. In the alveoli of a healthy lung, pO2 is estimated to be 105-110 mm Hg [101] with decreases to < 60 mm Hg in asthmatics or patients with COPD [102,103]. Since these O2 concentrations are often higher than those required to activate HIF-1 in vitro (e.g. [28]), HIF- activation in these conditions may not only be a consequence of hypoxic microenvironments within inflammatory lesions, but may also involve alternative pathways of HIF-1 stabilization and activation. The functional significance of HIF-1 activation within these disease states remains largely unknown, but is being increasingly addressed in studies with genetic manipulation of HIF-1, using conditional cell-specific deletion and/or overexpression strategies. In the following sections, we summarize the current knowledge with respect to the functional importance of HIF-1 in various aspects of inflammatory disease, including activation of inflammatory cell types and regulation of injury/repair processes and homeostasis in epithelia, and we will also discuss any demonstrated role of NO in these processes.

TABLE 1.

Inflammatory diseases with reported expression of HIF-1α in patient tissue

| Disease | HIF-1α localization | Effect on HIF-1α expression |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | submucosa | ↑ | [10] |

| COPD | bronchial epithium | ↑ | [163,164] |

| COPD | endothelial and alveolar septal cells | ↓ | [165] |

| Cystic fibrosis | unknown | ↑ | [164] |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | alveoloar epithelial cells | ↑ | [141] |

| Pulmonary hypertension | endothelial cells, alveolar macrophages | ||

| bronchial and vascular smooth muscle | |||

| bronchial epithelium | ↑ | [166] | |

| Chronic kidney disease | renal tubules | ↑ | [13] |

| Ischemic colitis | epithelium, interstitial inflammatory cells | ↑ | [167] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | epithelial cells, fibroblasts | ↑ | [14] |

| Atherosclerosis | macrophages, vascular endothelial cells | ↑ | [12,168-170] |

| smooth muscle arteries | ↑ | [12,169] | |

| perivascular region | ↑ | [170] | |

| inflammatory and hypoxic areas | ↑ | [171] | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | endothelial and synovial lining cells | ||

| fibroblasts, macrophages | ↑ | [172,173] | |

| Diabetic retinopathy | preretinal membranes | ↑ | [174,175] |

| intravitreous eye fluid | ↑ | [175] | |

| Neonatal lupus syndrome | connective heart tissue | ↑ | [176] |

| Celiac disease | villous enterocytes | ↑ | [177] |

| Psoriasis | epidermis and dermis | ↑ | [178] |

| Alzheimer disease | frontal cerebral cortices | ↓ | [179] |

| Multiple sclerosis | astrocytes and oligodendrocytes | ↑ | [180] |

HIF-1 mediated inflammatory responses in myeloid cells

Myeloid cells such as macrophages and neutrophils are recruited to sites of inflammation acting as front lines of defense during immune responses. Once at the inflammatory site, they facilitate microbial killing through the release of anti-microbial peptides, granule protease and production of ROS/RNS, as well as through phagocytosis of pathogens or cellular debris. Through the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines macrophages are able perpetuate the immune response by recruiting additional cells to the inflammatory site and, together with dendritic cells, participate in antigen presentation which plays a crucial role in linking the innate and adaptive immune responses.

As mentioned, low oxygen levels are a characteristic feature of inflammatory sites, indicating that myeloid cells must adapt to function in hypoxic environments. Indeed, cells of myeloid lineage derive their energy predominately through glycolysis [1] while several of their functions, including phagocytosis, cytokine secretion and survival have been shown to be under the regulation of hypoxia (1–5% O2) [4]. In this way, it stood to reason that as a central mediator of the response to hypoxia, HIF-1 could significantly impact upon myeloid cell function. Recently, genetic engineering approaches using a conditional Cre-LoxP recombination system employing the lysosome M promoter to specifically target and delete the Hif-1α gene in the myeloid cells of mice has demonstrated an essential role of HIF-1α in regulating the inflammatory functions of neutrophils and macrophages Group A streptococcus [104]. These pioneering studies elegantly demonstrated impaired induction of several genes (Vegf, Glut-1 and Tnf-α) in response to hypoxia in HIF-1α null peritoneal macrophages. Deficiency of HIF-1α also resulted in significantly lower concentrations of ATP in both peritoneal macrophages and neutrophils cultured in normoxia [104]. Additionally, HIF-1α deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages inoculated with Group B streptococci (GBS) displayed a marked defect in their bactericidal capacity and HIF-1α deficient peritoneal macrophages had diminished migration and invasion capacities, compared to wild type cells [104].

A separate set of studies utilizing these same mice confirmed a role for HIF-1α in myeloid cell mediated bactericidal activity. Bone marrow derived macrophages isolated from WT or HIF-1α−/− mice were inoculated with group A Streptococcus (GAS) or P. aeruginosa, both of which increased HIF-1α protein expression and HIF-1 transcriptional activity in WT cells. Macrophages deficient in HIF-1α displayed an impaired ability to undergo the intracellular bacterial killing under both normoxic and hypoxic (0.1% O2) conditions, and HIF-1α−/− mice were more susceptible to GAS infection which creates hypoxic conditions (pO2 < 10 mm Hg) [66]. Defects in bacterial killing were linked with decreased neutrophil expression of the antimicrobial molecules cathepsin G, cathelicidin related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP) and neutrophil elastase [66]. Similar bactericidal roles for HIF-1 have also been demonstrated in keratinocytes, where HIF-1 is constitutively expressed due to the hypoxic environment of normal mouse skin [105]. HIF activation has been shown to impact on several other aspects of neutrophil function including the induction of β2 integrin, which promotes neutrophil-epithelial binding [106], and the inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis [47] and subsequent recognition and phagocytosis by macrophages [107]. Expression of HIF-1α has been detected in biopsy specimens from asthmatic patients [10] which may have important consequences on myeloid cell function. In this way, heterozygote deficient HIF-1α (HIF-1α+/−) mice subject to the ovalbumin (OVA) model of allergic airway disease were protected from lung eosinophilia, which was associated with enhanced secretion of interferon-γ, compared to wild type litter mate controls [108], implicating pro-inflammatory roles of HIF-1 in the context of allergic asthma.

Interaction between NO and HIF-1 in macrophage function

As NO also mediates many of the vasodilatory and antimicrobial properties of macrophages [4], the interplay between NO and hypoxia induced signaling may be of particular importance to macrophage biology. To corroborate this point, a recent study using a combined approach of nuclear run on and microarray analysis compared the genetic profile of RAW 264.7 macrophages treated with hypoxia and/or DETA/NONOate [109]. This study identified 162 transcripts that were regulated only when cells were co-treated with hypoxia and NO as well as detecting 14 genes that were under the influence of both hypoxia and NO alone and were differentially regulated by the two treatments in combination. Collectively, these data suggest a dynamic crosstalk between NO and hypoxia signaling. A number of studies demonstrate that hypoxia up-regulates NOS2 activity in murine macrophages in a manner that is dependent upon an HRE sequence in the NOS2 promoter [110], and HIF-1α has a been shown to be a principal regulator of NOS2 induction and NO production in response to bacterial infection in bone marrow derived murine macrophages [66]. Intriguing recent studies indicate diverse roles of HIF in macrophage polarization and NO homeostasis [111]. While classical pro-inflammatory macrophages (M1 macrophages) respond primarily to Th1 cytokines, M2-polarized macrophages (alternatively activated macrophages) respond preferably to Th2 cytokines and possess immune suppressive functions. These various responses appear to be related to mRNA and protein expression of different HIF-α subunit isoforms, which confer antagonistic functions in regards to macrophage polarization and regulation of NO production. While induction of HIF-1α by Th1 cytokines was found to mediate upregulation of NOS2, the Th2 cytokine-mediated induction of HIF-2α led to increases in arginase1, an enzyme that competes with NOS2 for its common substrate, L-arginine. In addition to its importance in anti-microbial and pro-inflammatory properties, the interplay between NO and HIF-1 signaling may facilitate additional functional responses in macrophages including migration [112], oxidant metabolism [113] and accumulation of p53 [114].

HIF-1 mediated inflammatory responses in stromal cells

Epithelial cells within external organs form highly regulated and semi-permeable barriers that separate the organs internal aspect from their external environment, and are critical in inflammatory–immune responses, by acting as a primary barrier against inhaled or ingested microbes and other antigens and by producing diverse mediators that participate in host defense as well as epithelial repair processes or tissue remodeling. Accumulating recent evidence demonstrates a central role of HIF-1 in intrinsic immune and inflammatory reactions within the various epithelia which may have profound consequences for diseases such as asthma [10,13], chronic kidney disease [13], inflammatory bowel disease [14] and colitis [115].

HIF-1 and epithelial barrier protection

Several studies have revealed a role for HIF-1 in intestinal epithelial barrier protection. Initial observations in T84 or CaCo-2 colonic epithelial cells, cultured at a pO2 of 20 Torr, and in in vivo experiments using mice exposed to 8% O2, revealed that the intestinal barrier was highly resistant to changes elicited by hypoxia [115-118]. Examination of the mechanisms responsible for this adaptation revealed a HIF-1 dependent transcriptional program of genes that conferred enhancement of barrier function. As opposed to classical regulators of barrier function, such as the tight junction proteins claudin(s) and occludin, these genes functioned in diverse capacities including mucosal restitution (intestinal trefoil factor, ITF) [116] xenobiotic clearance (multidrug resistance, MDR1) [117], increased mucin production (MUC3) [119], and metabolism and signaling of extracellular nucleotides (ecto-5′-nucleotidase, CD73 [118]; adenosine kinase (AK) [120]; adenosine A2B receptor, (A2BR) [121]; equilibrative nucleoside transporter-2 (ENT2) [122]). The physiologic implications for HIF-1 activation in intestinal epithelium were further validated in mouse models that genetically repressed (Hif-1 −/−) or overexpressed (Vhlh) HIF-1 specifically in the intestinal epithelium. Using chemical model of colitis, these experiments demonstrated that loss of HIF-1 correlated with more severe clinical symptoms, including intestinal epithelial permeability, while increased HIF activity was protective [115].

Although various microorganisms are capable of increasing HIF-1 stabilization in epithelial cells [123-125], the importance of HIF-1 activation in bacterial infection, translocation across epithelia, and inflammatory disease is varied. Enhanced translocation of the gram positive bacteria E. faecalis across intestinal monolayers in response to hypoxia (pO2 20 mm Hg) was attributed to the induction of the platelet activating factor receptor (PAFr), a HIF-1 target gene [126]. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting either PAFr or HIF-1α significantly reduced bacterial translocation in these studies. Similarly, partial deficiency in HIF-1α (using HIF-1α +/− mice) ameliorated increases in intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation in a global trauma hemorrhagic shock (T/HS) model, and reduced T/HS-induced levels of IL-1β, COX2 and iNOS in the ileal mucosa [127]. In apparent contrast, HIF-1α deficient intestinal cells were more susceptible to epithelial barrier dysfunction upon exposure of to C. difficile toxin under normoxic conditions in vitro, as assessed by transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) [125]. Moreover, C. difficile toxin induced more severe intestinal inflammation in mice with an intestinal targeted deletion of HIF-1α [125]. Of note, toxin-induced accumulation of HIF-1α in this study was attenuated by NOS inhibitors, indicating the importance of NO [125]. Recent studies from our laboratory indicate that induction of NOS2 by pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to epithelial barrier restoration or protect against barrier dysfunction by oxidative stress [128], although at this point it is unclear whether this is related to NO-dependent activation of HIF-1. Collectively, these various studies suggest that HIF-1 dependent transcriptional programs provide an adaptive link for maintenance of barrier function during conditions of inflammation, which may in some cases be related to NO production, but may have varying roles depending on the nature of microbial infection.

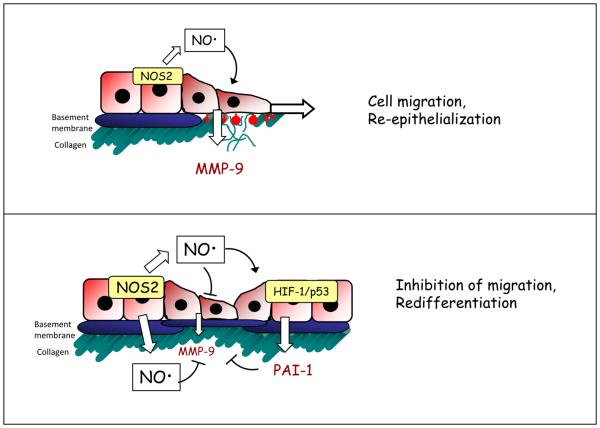

HIF-1 and NO in epithelial wound repair

Conditions of epithelial inflammation and injury are associated with a wound response program involving a complex of cell signaling pathways and changes in gene expression that promote epithelial cell migration and proliferation. A large number of studies have demonstrated that both HIF and NO can impact on cell migration and wound repair [129-135] and may play coordinating roles in these processes. Recent studies from our laboratory demonstrated that NO has multifactorial roles in wound responses in human bronchial epithelial cells cultured under normoxic conditions, with low nM concentrations promoting epithelial cell migration and wound closure, whereas >100 nM levels of NO, representative of inflammatory conditions, inhibited the cell migration and wound closure [87]. This latter response was associated with stabilization of HIF-1α and induction of HIF-1 target genes, and using cell transfection with a degradation-resistant HIF-1α mutant construct or HIF-1α targeted siRNA it was determined that NO-mediated inhibition of wound closure was dependent on HIF-1α accumulation. NO also resulted in p42/p44 MAPK dephosphorylation under these conditions, which would reduce HIF-1 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity, and led to enhanced phosphorylation and stabilization of p53. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of HIF-1 on epithelial cell migration may be largely related to non-transcriptional actions of HIF-1 but rather to extranuclear actions of HIF-1α on p53. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the diverse effects of NO on epithelial cell migration might represent different phases of a coordinated wound response, in which NO may facilitate cell migration at early stages and inhibit cell migration and potentially promote redifferentiation at later stages, to restore normal epithelial function. Activation of HIF-1α may be an important component of this latter phase. Stabilization of HIF-1 observed in a murine model of ischemic wounds (pO2 <10 mm Hg) has been linked with delayed wound epithelialization and epithelial proliferation, which was related to HIF-1 mediated expression of a microRNA (miR-210) that targeted and down regulated E2F3, a key facilitator of cell proliferation [136].

Figure 2. Schematic model of proposed actions of NO in airway epithelial regeneration following injury, and the involvement of HIF.

Initial stages of epithelial repair may be promoted by low concentrations of NO from NOS2, which promote epithelial cell migration in part by induction of repair genes such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (top panel). At later stages, elevated concentrations of NO may attenuate cell migration by suppressing MMP-9 expression and activation (through induction of PAI-1) and by activating p53 (lower panel). As indicated, some of these responses are mediated by the stabilization and activation of HIF-1 [87]. This biphasic control of cell migration by NO may be critical for a coordinated wound response and appropriate re-epithelialization. HIF-1α hypoxia inducible factor-1α; MMP-9 matrix metalloproteinase 9; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase2, PAI-1; plasminogen activator inhibitor-1.

In apparent contrast to these inhibitory effects of HIF-1 on cell migration and proliferation, HIF-1 has also been implicated in the promotion of wound healing and cell migration [13,133,137,138]. In an aspirin-induced model of gastric injury in rats, NOS2-derived NO was implicated in mucosal restitution via the HIF-1-mediated induction of TFF genes [137]. Similarly, the healing rate of full-thickness wounds in diabetic mice was promoted by the HIF-1 stabilizing agents DMOG and DFX and by adenovirus transfer of stabilized HIF-1α [133]. HIF-1 was also found to enhance migration of primary renal epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia in vitro through the induction of lysyl oxidase (Lox) genes [13]. It follows from these various findings that the overall role of HIF-1 in epithelial wound responses is complex and variable, but at least some of the HIF-1 related actions in epithelial wound healing are associated with NO signaling.

Role of HIF-1 in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tissue fibrosis

Several pathological conditions, such as tissue fibrosis or malignant transformation are associated with a phenomenon known as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transistion (EMT), a process in which epithelial cells de-differentiate, lose their polarity and cell-to-cell interactions, and undergo morphologic changes with more fibrobast-like displaying properties of increased motility and invasiveness [139]. EMT is characterized by loss of the expression of epithelial markers such as ZO-1 and E-cadherin and the appearance of mesenchymal markers such as -smooth muscle actin (SMA) and vimentin [139]. Tissue fibrosis leads to destruction and irreversible loss of normal tissue function that results, in part, from the maladaptive production of extracellular matrix (ECM) by fibroblasts and from cellular regeneration at sites of tissue injury [140].

The process of EMT has been increasingly implicated in the development of tissue fibrosis and various lines of recent evidence suggest a role for HIF-1 in this process. Enhanced levels of HIF-1α and HIF-1 target genes have been detected in several mouse models of renal [13] and pulmonary [141] fibrosis, as well as in human tissue samples from patients with chronic kidney disease [13] and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [141], suggesting that HIF-1 signaling may be relevant to the progression of these diseases. Indeed, HIF-1 was found to enhance EMT in primary renal epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia (1% O2) in vitro [13] and the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis was attenuated in mice genetically deficient in HIF-1α in proximal tubular epithelial cells following ureteral obstruction (resulting in ~1% O2) [13]. The importance of HIF-1 in the regulation of EMT is largely underscored in cancer cells. For example, renal clear cell carcinoma (RCC) cells that are deficient in the VHL tumor suppressor, resulting in constitutive HIF activation, displayed several properties of EMT including down regulation of Ecadherin and loss of cell-to-cell adhesion. These features were reversed in cells transfected with functional VHL, a dominant-negative HIF-1α mutant, or shRNA directed against HIF-1α [142]. Additional evidence for a role of HIF-1 in EMT includes observations that loss of VHL function within RCC cells resulted in down regulation of the tight junction proteins claudin-1 and occludin [143]. Inhibition of HIF-1α by siRNA restored levels of these proteins and enhanced the formation of TJ assembly, observations that may be related to the role(s) of HIF in epithelial barrier function discussed in the previous section.

Contribution of HIF-1 in the progression of EMT has been demonstrated in various non-cancer cell types subjected to prolonged (>24hr) hypoxia, including alveolar epithelial [144], tubule [145] and hepatocytes [146]. Common in these studies is the loss of epithelial markers, including E-cadherin and ZO-1, and increased expression of mesenchymal markers such as αSMA and vimentin. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) regulates diverse cellular functions including growth, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [147] and is considered to be the major cytokine inducer of EMT [147]. In this regard, TGF-β has been demonstrated to mediate EMT in cells from several different tissues, including hepatoctyes [146] and alveolar epithelial cells [144] and has been shown to play central roles in EMT mediated fibrosis [148,149]. HIF-1 is proposed contribute to EMT by impacting on TGF-β signaling through the upregulation of TGF-β mRNA and protein [132] and through increased TGF-β activity [132,133]. Reciprocally, TGF-β is reported to induce HIF-1α stability through the inhibition of PHD2 [150].

Recent studies suggest that EMT may also be regulated by NO. Inhibition of endogenous NOS activity with L-NAME in alveolar epithelial cells in vitro was found to result in spontaneous EMT, indicated by increased expression of SMA and a fibroblast like morphology [151]. Furthermore, features of TGF-β-mediated EMT in either alveolar epithelial cells or hepatocytes could be abrogated with co-treatment of exogenous NO or by overexpression of NOS2 [151,152]. Given the ability of NO to regulate HIF, its effects on EMT could conceivably be related to inhibition of HIF-1 signaling, although this still remains to be established.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

One of the take-home messages of this review is that hypoxic signaling and HIF activation is not only a feature of tissue hypoxia in e.g. organ development and tumor biology, but plays an increasingly recognized role in diverse pathophysiological conditions, ranging from infection and inflammation to tissue regeneration and fibrosis. While foci of tissue inflammation are associated with decreases in O2 availability, which may contribute to HIF activation and gene regulation, HIF expression and activation is also subject to regulation by a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-α, IL-1β), growth factors (e.g. EGF), various ROS, and NO and related metabolites. Thus, while HIF activation and HIF-mediated signaling were initially considered to function primarily in cellular adaptation to low O2 concentrations, these processes are now recognized as being centrally involved in the modulation of several features of the inflammatory response and tissue injury and remodeling related to chronic inflammation. With the advent of genetic mouse models that allow for specific conditional genetic HIF silencing in selected target cells or tissues, the functional importance of HIF activation in different disease scenarios is becoming increasingly apparent.

In spite of these advancements in our appreciation of HIF signaling, its biological relevance in many disease states is still incompletely identified. HIF-1 activation within different cell types may have congruous or opposing functions, and may have different roles at early or late stages of allergic asthma or other chronic inflammatory diseases. Indeed, while some studies claim a contribution of HIF-1 to disease pathology in conditions of acute or chronic inflammation, others indicate that the activation of HIF-1 largely serves a protective role against tissue injury, and contributes critically to tissue repair and regeneration. Observations of reduced HIF levels in neonatal diseases such as respiratory distress syndrome [153] highlight the importance of HIF during tissue development and would suggest that augmentation of HIF activation may be beneficial in this case. Some recent reports have documented associations of several HIF polymorphisms in various cancers [154,155], but is it not known to what extent these polymorphisms are also associated with other, non-malignant diseases. With continued use of genetic mouse models and further development of research tools to selectively interfere with HIF signaling, it is anticipated that we will soon gain additional important insights with respect to the importance of HIF in various chronic diseases associated with inflammation and tissue remodeling.

Given the intricate relationships between NO and O2 homeostasis, alterations in NOS expression/activation and NO production during inflammation will have important implications for hypoxic signaling and HIF-1 regulation in particular. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated many diverse actions of NO and SNOs on HIF activation and signaling, although the biological importance of NO with respect to regulating HIF is not always clear. For example, our recent studies indicate that HIF-1 activation in a mouse model of allergic asthma was unaffected in mice that lack NOS2, induction of which is a common feature of several inflammatory diseases including asthma [91]. However, findings that alterations in S-nitrosothiol status are often associated with altered HIF-1 activation in several in vivo models [91,92,98], and observations that HIF-1 activation may in some cases depend on other NOS isoforms [99], indicate the potential importance of NO in HIF regulation in vivo. Much of this unclarity is related to the divergent and sometimes opposing actions of NO (or related RNS) on HIF-1 activation depending on O2 status, and technical limitations of most in vitro studies of hypoxia that may not always apply to in vivo situations. Moreover, the extent of localized tissue hypoxia and the actual levels of available O2 in diverse disease conditions are not always clear. Because HIF-1 can contribute to NOS2 induction, the ability of NO to inhibit HIF-1 during hypoxia may point to a negative feedback relationship between HIF-1 and NO, similar to a demonstrated feedback of NO on NF-κB signaling. Future studies that more carefully evaluate the temporal associations in vivo between alterations in O2 status, NOS activation and NO production and metabolism, and HIF-1 activation, will be required to better address this issue and will enhance our understanding of the biological roles of NO or related RNS with respect to their involvement in HIF regulation.

A number of studies have pointed towards a role for S-nitrosylation of specific cysteines in NO-mediated activation of HIF-1. This would imply that alternative modifications of these cysteine residues by e.g. S-glutathionylation or S-alkylation by biological ROS or electrophiles may likewise be involved in HIF-1 regulation. In contrast to the demonstrated impact of S-nitrosylation on HIF-1 activation [57,92,96,98], we are unaware of data demonstrating the importance of alternative modifications of cysteine residues within HIF-1α or other critical proteins in the HIF pathway, although several studies have demonstrated a role for H2O2 or O2- from either mitochondria or from NOX enzymes in activation of HIF-1 [156,157]. Moreover, HIF-1 transcriptional activation and HIF-dependent gene expression is known to be subject to redox regulation by Ref-1 or thioredoxin-1 [158-161] and can be altered by several thiol-reactive agents, such as GSSG [60] or cyclopentenone prostaglandins [62,162]. Intriguingly, and analogous to NO, the cyclopentenone prostaglandin-J2 was found to promote HIF-1 during normoxia, but inhibit HIF-1-dependent gene expression during hypoxia [162], again highlighting the critical importance of O2 status in redox-dependent regulation of HIF activation. Therefore, it is highly plausible that the identified mechanisms of HIF regulation by NO or related RNS may be expanded to analogous modes of HIF regulation by other thiol-reactive mediators, thus leading to a broader appreciation of redox-dependent regulation of hypoxia-induced responses and HIF signaling.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge research support from NIH to A.v.d.V. (HL074295, HL068865 and HL085646) and a T32 training fellowship to N.O. (ES007122).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kominsky DJ, Campbell EL, Colgan SP. Metabolic shifts in immunity and inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4062–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sitkovsky M, Lukashev D. Regulation of immune cells by local-tissue oxygen tension: HIF1 alpha and adnosin receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:712–21. doi: 10.1038/nri1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nizet V, Johnson RS. Interdependence of hypoxic and innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:609–17. doi: 10.1038/nri2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JS, Lee JA, Underwood JC, Harris AL, Lewis CE. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: relevance to disease mechanisms. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:889–900. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semenza GL. Regulation of oxygen homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:97–106. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010;29:625–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onnis B, Rapisarda A, Melillo G. Development of HIF-1 inhibitors for cancer therapy. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2780–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris AL. Hypoxia--a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:721–32. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SY, Kwon S, Kim KH, Moon HS, Song JS, Park SH, Kim YK. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia-inducible factor in the airway of asthmatic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:794–9. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollander AP, Corke KP, Freemont AJ, Lewis CE. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha by macrophages in the rheumatoid synovium: implications for targeting of theraputic genes to the inflamed joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1540–4. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1540::AID-ART277>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vink A, Schoneveld AH, Lamers D, Houben AJ, van dr Groep P, van Dist PJ, Pasterkamp G. HIF-1 alpha expression is associated with an atheromatous inflammatory plaque phenotype and upregulated in activated macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:e69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins DF, Kimura K, Bernhardt WM, Shrimanker N, Akai Y, Hohenstein B, Saito Y, Johnson RS, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Eckardt KU, Iwano M, Haase VH. Hypoxia promotes fibrogensis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3810–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI30487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Maltezos E, Papazoglou D, Simopoulos C, Gatter KC, Harris AL, Koukourakis MI. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha and 2alpha overexpression in inflammatory bowl disease. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:209–13. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bove PF, van der Vliet A. Nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen specis in airway epithelial signaling and inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Md. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Semenza GL, Wang GL. A nuclear factor induced by hypoxia via de novo protein synthesis binds to the human erythropoietin gene enhancer at a site required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5447–54. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.12.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dehne N, Brune B. HIF-1 in the inflammatory microenvironment. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1791–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddad JJ, Harb HL. Cytokines and the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:461–83. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brune B, Zhou J. Nitric oxide and superoxide: interference with hypoxic signaling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: control of oxygen homeostasis in health and disease. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:614–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: oxygen homeostasis and disease pathophysiology. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:345–50. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294:1337–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidemann A, Johnson RS. Biology of HIF-1 alpha. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:621–7. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Riordan MV, Tian YM, Bullock AN, Welford RW, Elkins JM, Oldham NJ, Bhattacharya S, Gleadle JM, Ratcliffe PJ, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) asparagine hydroxylase is identical to factor inhibiting HIF (FIH) and is related to the cupin structural family. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26351–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1466–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.991402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang BH, Semenza GL, Bauer C, Marti HH. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O2 tension. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1172–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson MA, Baumgardner JE, Good VP, Otto CM. Physiological and hypoxic O2 tensions rapidly regulate NO production by stimulated macrophages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1079–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00469.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewhirst MW. Intermittent hypoxia furthers the rationale for hypoxia-inducible factor-1 targeting. Cancer Res. 2007;67:854–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frede S, Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Fandrey J. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors during inflammation. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:405–19. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frede S, Stockmann C, Freitag P, Fandrey J. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide induces HIF-1 activation in human monocytes via p44/42 MAPK and NF-kappaB. Biochem J. 2006;396:517–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oda T, Hirota K, Nishi K, Takabuchi S, Oda S, Yamada H, Arai T, Fukuda K, Kita T, Adachi T, Semenza GL, Nohara R. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 during macrophage differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C104–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00614.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page EL, Robitaille GA, Pouyssegur J, Richard DE. Induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha by transcriptional and translational mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48403–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walczak-Drzewicka A, Ratajewski M, Wagner W, Dastych J. HIF-1 alpha is up-regulated in activated mast cells by a process that involves calcinurin and NFAT. J Immunol. 2008;181:1665–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mint E, Ernest I, Michel G, Roland I, Remacle J, Raes M, Michiels C. HIF1A gene transcription is dependent on a core promoter sequence encompassing activating and inhibiting sequences located upstream from the transcription initiation site and cis elements located within the 5′UTR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:534–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1 alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–11. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorlach A. Regulation of HIF-1 alpha at the transcriptional level. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:3844–52. doi: 10.2174/138161209789649420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frede S, Freitag P, Otto T, Heilmaier C, Fandrey J. The proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1 beta and hypoxia coopratively induce the expression of adrenomedullin in ovarian carcinoma cells through hypoxia inducible factor 1 activation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4690–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Ponti C, Carini R, Alchera E, Nitti MP, Locati M, Albano E, Cairo G, Tacchini L. Adenosin A2a receptor-mediated, normoxic induction of HIF-1 through PKC and PI-3K-depndent pathways in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:392–402. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasuno K, Takabuchi S, Fukuda K, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Yodoi J, Adachi T, Semenza GL, Hirota K. Nitric oxide induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation that is dependent on MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2550–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandau KB, Faus HG, Brune B. Induction of hypoxia-inducible-factor 1 by nitric oxide is mediated via the PI 3K pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:263–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galban S, Gorospe M. Factors interacting with HIF-1 alpha mRNA: novel therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:3853–60. doi: 10.2174/138161209789649376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janssen-Heininger YM, Poynter ME, Aesif SW, Pantano C, Ather JL, Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Anathy V, van der Velden J, Irvin CG, van der Vliet A. Nuclear factor kappaB, airway epithelium, and asthma: avenues for redox control. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:249–55. doi: 10.1513/pats.200806-054RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliver KM, Garvey JF, Ng CT, Veale DJ, Fearon U, Cummins EP, Taylor CT. Hypoxia activates NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through the canonical signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2057–64. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belaiba RS, Bonelo S, Zahringer C, Schmidt S, Hess J, Kitzmann T, Gorlach A. Hypoxia up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha transcription by involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nuclear factor kappaB in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4691–7. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walmsley SR, Print C, Farahi N, Peyssonnaux C, Johnson RS, Cramer T, Sobolewski A, Condliffe AM, Cowburn AS, Johnson N, Chilvers ER. Hypoxia-induced neutrophil survival is mediated by HIF-1 alpha-dependent NF-kappaB activity. J Exp Med. 2005;201:105–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peyssonnaux C, Cejudo-Martin P, Doedens A, Zinkernagel AS, Johnson RS, Nizet V. Cutting edge: Essential role of hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha in development of lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis. J Immunol. 2007;178:7516–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richard DE, Berra E, Gothie E, Roux D, Pouyssegur J. p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases phosphorylate hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1 alpha) and enhance the transcriptional activity of HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32631–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mylonis I, Chachami G, Samiotaki M, Panayotou G, Paraskeva E, Kalousi A, Georgatsou E, Bonanou S, Simos G. Identification of MAPK phosphorylation sites and their role in the localization and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-l alpha. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33095–106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen D, Li M, Luo J, Gu W. Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13595–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki H, Tomida A, Tsuruo T. Dephosphorylated hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha as a mediator of p53-dependent apoptosis during hypoxia. Oncogene. 2001;20:5779–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flugel D, Gorlach A, Michiels C, Kietzmann T. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha and mediates its destabilization in a VHL-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3253–65. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00015-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeong JW, Bae MK, Ahn MY, Kim SH, Sohn TK, Bae MH, Yoo MA, Song EJ, Lee KJ, Kim KW. Regulation and destabilization of HIF-l alpha by ARD1-mediated acetylation. Cell. 2002;111:709–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bae SH, Jeong JW, Park JA, Kim SH, Bae MK, Choi SJ, Kim KW. Sumoylation increases HIF-1 alpha stability and its transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berta MA, Mazure N, Hattab M, Pouyssegur J, Brahimi-Horn MC. SUMOylation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha reduces its transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:646–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li F, Sonveaux P, Rabbani ZN, Liu S, Yan B, Huang Q, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Li CY. Regulation of HIF-1 alpha stability through S-nitrosylation. Mol Cell. 2007;26:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haddad JJ, Land SC. O(2)-evoked regulation of HIF-1alpha and NF-kappaB in perinatal lung epithelium requires glutathione biosynthesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L492–503. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.3.L492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haddad JJ, Olver RE, Land SC. Antioxidant/pro-oxidant equilibrium regulates HIF-1alpha and NF-kappa B redox sensitivity. Evidence for inhibition by glutathione oxidation in alveolar epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21130–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tajima M, Kurashima Y, Sugiyama K, Ogura T, Sakagami H. The redox state of glutathione regulates the hypoxic induction of HIF-1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;606:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duyndam MC, Hulscher TM, Fontijn D, Pinedo HM, Boven E. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha protein by the oxidative stressor arsenite. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48066–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106282200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olmos G, Conde I, Arenas I, Del Peso L, Castellanos C, Landazuri MO, Lucio-Cazana J. Accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha through a novel electrophilic, thiol antioxidant-sensitive mechanism. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2098–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moos PJ, Edes K, Cassidy P, Massuda E, Fitzpatrick FA. Electrophilic prostaglandins and lipid aldehydes repress redox-sensitive transcription factors p53 and hypoxia-inducible factor by impairing the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:745–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Wouters EF, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YM. Nitric oxide and redox signaling in allergic airway inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:129–43. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palmer LA, Johns RA. Hypoxia upregulates inducible (Type I) nitric oxide synthase in an HIF-1 dependent manner in rat pulmonary microvascular but not aortic smooth muscle cells. Chest. 1998;114:33S–34S. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1_supplement.33s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peyssonnaux C, Datta V, Cramer T, Doedens A, Theodorakis EA, Gallo RL, Hurtado-Ziola N, Nizet V, Johnson RS. HIF-1 alpha expression regulates the bactericidal capacity of phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1806–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Inhibition of NF-kappa B by S-nitrosylation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1688–93. doi: 10.1021/bi002239y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kelleher ZT, Matsumoto A, Stamler JS, Marshall HE. NOS2 regulation of NF-kappaB by S-nitrosylation of p65. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30667–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Korn SH, Vos N, Guala AS, Wouters EF, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YM. Nitric oxide represses inhibitory kappaB kinase through S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8945–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400588101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mateo J, Garcia-Lecea M, Cadnas S, Hernandez C, Moncada S. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha by nitric oxide through mitochondria-dependent and -independent pathways. Biochem J. 2003;376:537–44. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brune B, Zhou J. The role of nitric oxide (NO) in stability regulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:845–55. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Tug S, Kirsch M, Fandrey J. Oxygn-sensing under the influence of nitric oxide. C Signa. 2010;22:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu W, Charles IG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide: orchestrating hypoxia regulation through mitochondrial respiration and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Cell Res. 2005;15:63–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor CT, Moncada S. Nitric oxide, cytochrome C oxidase, and the cellular response to hypoxia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:643–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moncada S, Erusaimsky JD. Does nitric oxide modulate mitochondrial energy generation and apoptosis? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:214–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hagen T, Taylor CT, Lam F, Moncada S. Redistribution of intracellular oxygen in hypoxia by nitric oxide: effect on HIF1 alpha. Science. 2003;302:1975–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1088805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang LE, Willmore WG, Gu J, Godberg MA, Bunn HF. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation by carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Implications for oxygen sensing and signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9038–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Callapina M, Zhou J, Schmid T, Kohl R, Brun B. NO restores HIF-1 alpha hydroxylation during hypoxia: role of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Bio Med. 2005;39:925–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Yamac H, Trinidad B, Fandrey J. Nitric oxide modulates oxygen sensing by hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent induction of prolyl hydroxylase 2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1788–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, Tug S, Trinidad B, Oehme F, Yamac H, Wotzlaw C, Flamme I, Fandrey J. Nuclear oxygen sensing: induction of endogenous prolyl-hydroxylase 2 activity by hypoxia and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31745–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knowles HJ, Raval RR, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Effect of ascorbate on the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1764–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]