Abstract

Histone acetylation and deacetylation play an important role in epigenetic controls of gene expression. HISTONE DEACETYLASE6 (HDA6) is a REDUCED POTASSIUM DEPENDENCY3-type histone deacetylase, and the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) hda6 mutant axe1-5 displayed a late-flowering phenotype. axe1-5/flc-3 double mutants flowered earlier than axe1-5 plants, indicating that the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 was FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) dependent. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation, in vitro pull-down, and coimmunoprecipitation assays revealed the protein-protein interaction between HDA6 and the histone demethylase FLD. It was found that the SWIRM domain in the amino-terminal region of FLD and the carboxyl-terminal region of HDA6 are responsible for the interaction between these two proteins. Increased levels of histone H3 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation at FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 were found in both axe1-5 and fld-6 plants, suggesting functional interplay between histone deacetylase and demethylase in flowering control. These results support a scenario in which histone deacetylation and demethylation cross talk are mediated by physical association between HDA6 and FLD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis indicated that HDA6 bound to the chromatin of several potential target genes, including FLC and MAF4. Genome-wide gene expression analysis revealed that, in addition to genes related to flowering, genes involved in gene silencing and stress response were also affected in hda6 mutants, revealing multiple functions of HDA6. Furthermore, a subset of transposons was up-regulated and displayed increased histone hyperacetylation, suggesting that HDA6 can also regulate transposons through deacetylating histone.

In eukaryotic cells, gene activity is controlled not only by DNA sequences but also by epigenetic marks, which can be transmitted to a cell’s progeny during mitosis or meiosis. Epigenetic changes involve the modification of DNA activity by methylation, histone modifications, or chromatin remodeling without alteration of the nucleotide sequence (Berger, 2007). Histone modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and ADP ribosylation. The functional consequences of histone modifications can be direct, causing structural changes to chromatin, or indirect, acting through the recruitment of effector proteins. All histone modifications are removable, which may provide a versatile way for regulating gene expression during plant development and the plant response to environmental stimuli. The reversible acetylation and deacetylation of specific Lys residues on core histone N-terminal tails is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases (HDAs or HDACs; Pandey et al., 2002; Chen and Tian, 2007). The action of both enzymes generates patterns of acetylation that may specify downstream biological processes such as transcriptional regulation. In general, hyperacetylated histones are associated with gene activation, whereas hypoacetylated histones are related to gene repression. Although histone acetylation is an integral part of transcriptional regulatory systems, little is known regarding its physiological roles and downstream target genes in plants.

More recent studies indicated that histone modifications including acetylation are involved in plant flowering (He and Amasino, 2005; Dennis and Peacock, 2007). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), flowering time is controlled by several pathways, including the photoperiod, gibberellin, autonomous, and vernalization pathways (Boss et al., 2004; Henderson and Dean, 2004). FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) is a key regulator of flowering, which negatively regulates downstream flowering activators such as FT and SOC1 (Michaels and Amasino, 2001; Helliwell et al., 2006). High expression of FLC results in a delayed-flowering phenotype. In the autonomous mutant fld, FLC displays hyperacetylation of histone H3 and H4, and it is proposed that FLD might participate in the deacetylation of FLC chromatin as a component of a HDAC complex (He et al., 2003). FLD encodes a plant ortholog of the human protein Lys-Specific Demethylase1 (LSD1) that is involved in H3K4 demethylation (Jiang et al., 2007). However, the histone deacetylase activity associated with FLD is unknown. Our previous studies demonstrated that the Arabidopsis HISTONE DEACETYLASE6 (HDA6) mutant, axe1-5, and HDA6-RNAi (for RNA interference) plants displayed a delayed-flowering phenotype (Wu et al., 2008). Furthermore, FLC was up-regulated and hyperacetylated in axe1-5 and HDA6-RNAi plants, suggesting that HDA6 may regulate flowering by repressing FLC expression.

In this study, we further investigate the function of HDA6 and its interaction with FLD. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), in vitro pull-down, and coimmunoprecipitation assays revealed direct protein-protein interaction between HDA6 and FLD, suggesting that they could act together in a protein complex. Increased levels of histone H3 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation in FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 were found in both axe1-5 and fld-6 plants, indicating functional interplay between histone deacetylase and demethylase through HDA6 and FLD interaction in flowering control.

RESULTS

The Late-Flowering Phenotype of axe1-5 Is FLC Dependent

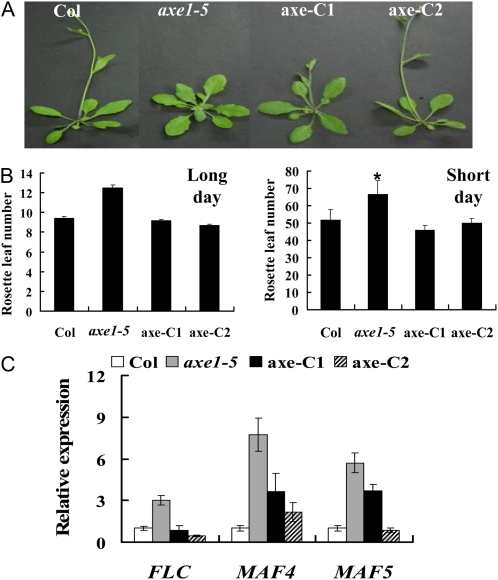

Previously, we reported that the Arabidopsis HDA6 mutant, axe1-5, displayed a late-flowering phenotype (Wu et al., 2008). To confirm that the delayed-flowering phenotype was indeed caused by the HDA6 mutation in axe1-5 plants, a 35S::HDA6-FLAG transgene was introduced into axe1-5 plants by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (Clough and Bent, 1998). Two independent transgenic lines, axe-C1 and axe-C2, expressing 35S::HDA6-FLAG were generated. Both axe-C1 and axe-C2 plants expressing the transgene flowered earlier than axe1-5 plants (Fig. 1, A and B). In addition, the expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 was decreased in the axe-C1 and axe-C2 plants (Fig. 1C). Rescue of the delayed-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 plants by expression of the 35S::HDA6-FLAG transgene suggests that the delayed-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 plants is indeed due to the HDA6 mutation.

Figure 1.

Complementation of the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 by overexpressing 35S:HDA6-FLAG. A, axe1-5 and the complementation lines (axe-C1 and axe-C2) grown under LD conditions compared with the Col wild type. B, Rosette leaf numbers at bolting of Col, axe1-5, axe-C1, and axe-C2 plants grown under LD and SD conditions. At least 20 plants were scored for each line. Error bars indicate sd. * Under SD conditions, most axe1-5 plants did not flower 120 d after germination, and the rosette leaf number was counted at 120 d. C, qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in Col, axe1-5, axe-C1, and axe-C2 plants grown under LD conditions for 20 d. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

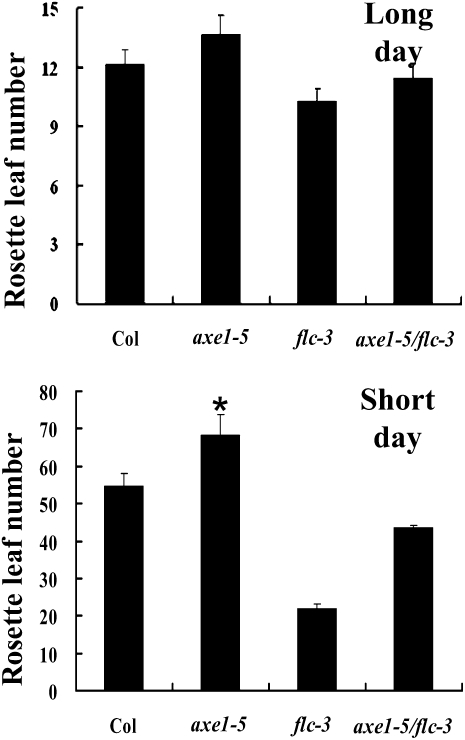

FLC is a major transcription repressor in the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive development stages (Michaels and Amasino, 2001). To investigate whether the delayed-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 was dependent on high FLC expression, we generated the axe1-5/flc-3 double mutant. axe1-5/flc-3 double mutants flowered earlier than axe1-5 plants both under long-day (LD) and short-day (SD) conditions (Fig. 2), indicating that the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 was FLC dependent. However, axe1-5/flc-3 plants flowered later than flc-3 single mutant plants, suggesting that a portion of the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 mutants could be due to other floral repressors (Deng et al., 2007). Consistent with this hypothesis, the expression of two additional MADS box genes in the FLC clade, MAF4 and MAF5, was also up-regulated in axe1-5 mutants (Fig. 1C).

Figure 2.

FLC-dependent late flowering in axe1-5. Rosette leaf numbers at bolting of Col, axe1-5, flc-3, and axe1-5/flc-3 plants grown under LD and SD conditions are shown. Error bars indicate sd. At least 20 plants were scored for each line. * Under SD conditions, most axe1-5 plants did not flower 120 d after germination, and the rosette leaf number was counted at 120 d.

Histone H3 Acetylation and H3K4 Trimethylation Levels of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 Are Increased in axe1-5 and fld-6 Plants

To analyze whether the higher expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in axe1-5 mutants is related to histone hyperacetylation in the chromatins, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was used to analyze the histone H3 acetylation level of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5. As shown in Figure 3, hyperacetylation of histone H3 was found in the first exon and first intron regions of FLC and MAF4 as well as in the first exon of MAF5, suggesting that HDA6 might regulate the expression of these genes by chromatin deacetylation.

Figure 3.

Levels of H3K9K14Ac and H3K4Me3 in FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 chromatin. A, Schematic structure of genomic sequences of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 and the regions examined by ChIP. FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 have a similar genomic structure, and black boxes represent exons. B to D, Relative levels of H3K9K14Ac and H3K4Me3 in FLC (B), MAF4 (C), and MAF5 (D) in Col, axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 seedlings grown under LD conditions for 10 d. The amounts of DNA after ChIP were quantified and normalized to an internal control (ACTIN2). The fold enrichments of axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 over Col at the indicated regions are shown. The values shown are means ± sd. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

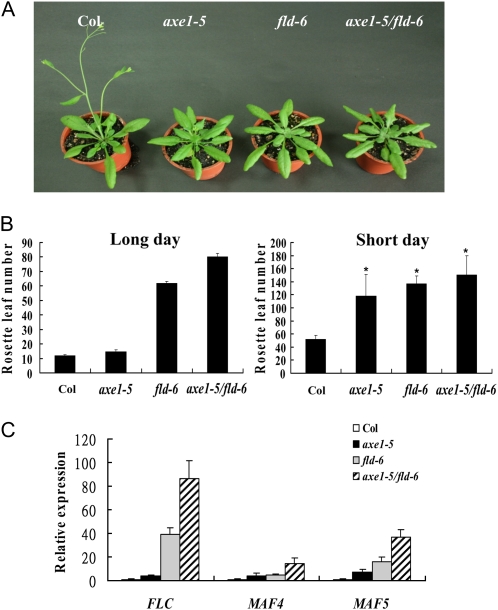

Another flowering-autonomous pathway mutant, fld, was also shown to have increased histone acetylation levels at the FLC locus (He et al., 2003). The T-DNA insertion mutant line from the SAIL T-DNA collection (SAIL_642_C05.v2), fld-6, carries a T-DNA insertion in the second exon of FLD (Jin et al., 2008). We determined flowering time of axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 double mutants under both LD and SD conditions (Fig. 4, A and B). fld-6 mutants flowered much later than axe1-5 mutants under LD conditions. axe1-5/fld-6 double mutants flowered later than both axe1-5 and fld-6 single mutants, suggesting that HDA6 and FLD may independently regulate flowering in an additive way. We compared the expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. As shown in Figure 4C, we observed the higher expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants compared with wild-type ecotype Columbia (Col) plants. In addition, the FLC transcript level of fld-6 plants was higher than that of axe1-5 plants, whereas axe1-5/fld-6 plants displayed the highest level of FLC expression, which is consistent with their phenotype difference in flowering time.

Figure 4.

Phenotypes of axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6. A, axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants grown under LD conditions compared with the Col wild type. B, Rosette leaf numbers at bolting of Col, axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants grown under LD and SD conditions. Error bars indicate sd. At least 20 plants were scored for each line. * Some axe1-5 plants and all of the fld-6 and axe1-5/fld-6 plants did not flower 220 d after germination, and the rosette leaf number was counted at 220 d. C, qRT-PCR analysis of the expression of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in Col, axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants grown under LD conditions for 20 d. The values shown are means ± sd. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

We compared the histone H3 acetylation levels of fld-6 and the double mutant axe1-5/fld-6 with that of axe1-5. Hyperacetylation of histone H3 was found in the first exon and first intron regions of FLC and MAF4 as well as in the first exon of MAF5 in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 (Fig. 3, B–D). These results indicate that both HDA6 and FLD may regulate FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 expression by histone acetylation during the transition switch from the vegetative stage to reproductive development. We also analyzed H3K4 trimethylation levels of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in axe1-5 and fld-6 plants. Increased H3K4 trimethylation was found in the first intron region of FLC, the first exon of MAF4, and all three regions of MAF5 in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 (Fig. 3, B–D).

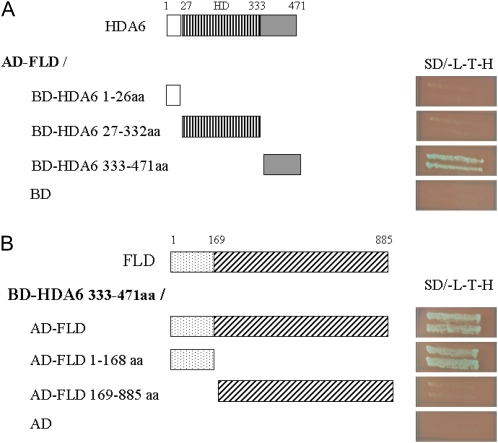

Interaction of HDA6 and FLD

A yeast two-hybrid assay was used to examine whether there is a direct protein interaction between FLD and HDA6. It was found that the full-length FLD interacted with the C-terminal region (amino acids 333–471) of HDA6 (Fig. 5A); this region is characterized by high Asp content. Further analysis indicated that the C-terminal region of HDA6 interacted with the FLD N-terminal region (Fig. 5B) that contains a SWI3P, Rsc8p, and Moira (SWIRM) domain (Aravind and Iyer, 2002). These results suggest that FLD can directly interact with HDA6, and the SWIRM domain in the N-terminal region of FLD and the C-terminal region of HDA6 are responsible for the interaction between these two proteins. FLD contains a SWIRM domain that is found in many chromosomal proteins involved in chromatin modifications or remodeling (Qian et al., 2005). The interaction of FLD amino acids 1 to 168 with the HDA6 C-terminal region suggests that the SWIRM domain might act as an important link among chromatin-remodeling proteins.

Figure 5.

HDA6 interacted with FLD in yeast two-hybrid assays. A, Different regions of HDA6 fused with the Gal4 binding domain (BD) and the full-length FLD fused with the Gal4 activation domain (AD) were cotransformed into the yeast strain AH109. B, Different regions of FLD fused with AD and the C-terminal fragment of HDA6 fused with BD were cotransformed into the yeast strain AH109. The transformants were plated onto plates with SD/-Leu-Trp-His/3-amino-1,2,4-triazole/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside for 3 d. aa, Amino acids. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

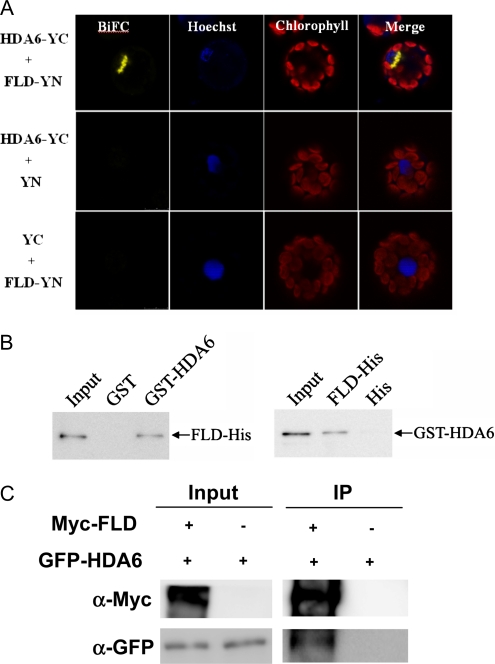

BiFC was used to further determine the interaction between HDA6 and FLD. Both HDA6 and FLD were fused to the N-terminal 174-amino acid portion of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the pEarleyGate201 vector (pEarleyGate201-YN) as well as the C-terminal 66-amino acid portion of YFP in the pEarleyGate202 vector (pEarleyGate202-YC; Lu et al., 2010). The corresponding constructs were codelivered into protoplasts of Arabidopsis, and fluorescence was observed using a confocal microscope. As shown in Figure 6A, yellow fluorescence was observed at the nuclear periphery when HDA6-YC was cotransformed with FLD-YN. Similar results were also observed when HDA6-YN was cotransformed with FLD-YC (Supplemental Fig. S1). These data indicate that HDA6 interacts with FLD and that the interaction site is at the nuclear periphery. Recent studies suggest that the peripheral zone of the nucleus is the area associated with the regulation of gene expression, especially gene silencing (Deniaud and Bickmore, 2009).

Figure 6.

HDA6 physically interacted with FLD. A, BiFC in Arabidopsis protoplasts showing interaction between HDA6 and FLD in living cells. HDA6 and FLD fused with the N terminus (YN) or the C terminus (YC) of YFP were cotransfected into protoplasts and visualized using confocal microscopy. As a negative control, HDA6 and FLD fused with YN or YC and empty vectors (YN and YC) were cotransfected into protoplasts. B, HDA6 interacted with FLD in a pull-down assay. GST-HDA6 or GST was incubated with FLD-His and GST affinity resin, and the bound proteins were then eluted from resin and probed with the anti-His antibody (left panel). FLD-His or His was incubated with GST-HDA6 and His affinity resin, and the bound proteins were then eluted from resin and probed with the anti-GST antibody (right panel). C, In vivo interaction between HDA6 and FLD in tobacco. Agrobacterium cultures carrying 35S:GFP-HDA6 and 35S:Myc-FLD were coinfiltrated into tobacco leaves. Transiently expressed GFP-HDA6 and Myc-FLD were analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation. Crude extracts (input) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-Myc antibody and analyzed by western blotting.

The interaction between HDA6 and FLD was further analyzed by in vitro pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation assays. For in vitro pull-down assay, purified FLD-His recombinant protein was incubated with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-HDA6 protein. As shown in Figure 6B, FLD-His was pulled down by GST-HDA6. Similarly, GST-HDA6 was also pulled down by FLD-His. These results indicate that HDA6 is directly associated with FLD. For coimmunoprecipitation assay, a tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) transient expression system was used (Yang et al., 2008). Tobacco leaves were infiltrated with Agrobacterium cultures carrying 35S:GFP-HDA6 and 35S:Myc-FLD, and leaf extracts were analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation. As shown in Figure 6C, GFP-HDA6 was coimmunoprecipitated by Myc-FLD. The interaction was specific, as GFP-HDA6 was not detected in the absence of Myc-FLD.

Genome-Wide Transcriptomic Analysis of HDA6-RNAi Plants

We compared the gene expression profiles of the HDA6-RNAi plants (cs24039) and ecotype Wassilewskija (Ws) wild-type plants by using Affymetrix microarray. Total RNA was isolated from rosette leaves of 3-week-old plants growing under SD conditions (16 h of dark and 8 h of light). Three independent biological samples were used to do microarray analysis, and microarray data were analyzed by the National Institute of Aging Array analysis software (Sharov et al., 2005). Those genes identified by 2-fold filtered increase or decrease and with P ≤ 0.05 were considered to have significant expression differences. Compared with Ws, 441 genes were up-regulated but only 46 genes were down-regulated in HDA6-RNAi plants (Supplemental Tables S3 and S4), supporting the generally accepted idea that a HDAC acts mainly as a transcriptional repressor. Those genes affected by HDA6 are involved in a variety of biological processes (Supplemental Fig. S2). In particular, 9% of genes are involved in developmental processes, including flowering regulation, 5% of genes are involved in gene silencing, and 12% of genes are involved in stress response (Supplemental Fig. S2).

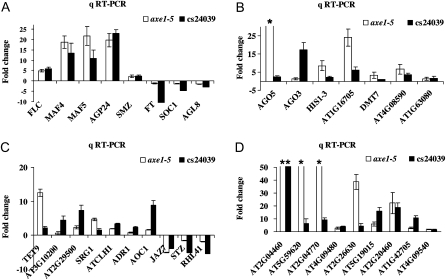

The microarray analysis revealed that a number of genes involved in flowering were up- or down-regulated in HDA6-RNAi plants (Table I). The cs24039 HDA6-RNAi line was previously shown to display a similar phenotype as compared with the axe1-5 mutant (Wu et al., 2008). We further used qRT-PCR to confirm the expression of those genes identified by microarray in HDA6-RNAi (cs24039) as well as axe1-5 plants. Eight genes related to flowering were analyzed by qRT-PCR, and all of them showed a correlation between qRT-PCR and microarray data in both HDA6-RNAi and axe1-5 plants (Fig. 7A). As expected, the expression of the floral repressors FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 was up-regulated, whereas the expression of the floral activators FT and SOC1 was down-regulated. In addition to FLC, MAF4, and MAF5, two additional MADS box genes, AGL37 and AT1G59930, were also up-regulated in axe1-5 and HDA6-RNAi plants.

Table I. Selected genes affected by HDA6 in microarray analysis.

| Gene Name | Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Code | Ratioa | P | Description |

| Genes involved in flowering | ||||

| MAF4b | AT5G65070 | 12.2 | 1.00E-05 | MADS box protein, negative regulator of flowering |

| FLCb | AT5G10140 | 8.6 | 1.00E-05 | MADS box protein, negative regulator of flowering |

| MAF5b | AT5G65080 | 7.6 | 1.30E-03 | MADS box protein, negative regulator of flowering |

| AGP24b | AT5G40738 | 6.2 | 1.00E-05 | Most highly expressed in pollen |

| AT1G52000 | AT1G52000 | 3.5 | 1.00E-05 | Flower development |

| AT5G38440 | AT5G38440 | 3.5 | 4.90E-02 | Self-incompatibility protein relative |

| AT3G17010 | AT3G17010 | 3.4 | 1.40E-03 | Expressed in stamen primordia |

| OPR3 | AT2G06050 | 3.2 | 1.00E-04 | Male sterile and pollen dehiscence |

| ARPN | AT2G02850 | 2.3 | 3.00E-04 | Involved in anther development and pollination |

| SMZb | AT3G54990 | 2.3 | 1.00E-05 | AP2 domain transcription factor |

| UNE18 | AT5G02100 | 2.3 | 1.00E-05 | Double fertilization forming |

| MBP2 | AT1G52030 | 2.1 | 1.00E-04 | Flower development |

| AGL8b | AT5G60910 | −3.2 | 5.00E-04 | Positive regulation of flower development |

| SPL5 | AT3G15270 | −2.5 | 1.40E-03 | Involved in regulation of flowering |

| SOC1b | AT2G45660 | −2.4 | 1.25E-02 | Promotes flowering |

| FTb | AT1G65480 | −2.3 | 1.10E-03 | Promotes flowering |

| AT1G04770 | AT1G04770 | −2.1 | 1.00E-05 | Male sterility MS5 family protein |

| HAT2 | AT5G47370 | −1.8 | 1.40E-03 | Homeobox-Leu zipper genes |

| Genes involved in gene silencing | ||||

| AGO5b | AT2G27880 | 12.4 | 4.30E-03 | Similar to AGO1 (ARGONAUTE1) |

| AGO3b | AT1G31290 | 5.8 | 3.80E-03 | Similar to AGO2 (ARGONAUTE2) |

| HIS1-3b | AT2G18050 | 3.7 | 1.00E-05 | HISTONE 1H-3 |

| AT1G16705b | AT1G16705 | 3.5 | 1.73E-02 | P300/CBP acetyltransferase-related protein |

| AT5G64572 | AT5G64572 | 2.4 | 1.00E-04 | Potential natural antisense gene |

| AT1G63080b | AT1G63080 | 2.3 | 2.50E-02 | Transacting siRNA-generating locus |

| DMT7b | AT5G14620 | 2.1 | 3.69E-02 | Putative DNA methyltransferase |

| AT4G08590b | AT4G08590 | 2.1 | 3.00E-03 | Similar to VIM1 |

| AT2G33815 | AT2G33815 | −2.6 | 7.00E-04 | Potential natural antisense gene |

| Transposons | ||||

| AT5G59620b | AT5G59620 | 25.8 | 1.00E-05 | CACTA-like transposase family |

| AT2G04770b | AT2G04770 | 16.1 | 1.00E-05 | CACTA-like transposase family |

| AT5G30450 | AT5G30450 | 9.4 | 5.00E-04 | CACTA-like transposase family |

| AT5G19015b | AT5G19015 | 6.7 | 3.10E-03 | CACTA-like transposase family |

| AT3G29650 | AT3G29650 | 4 | 4.63E-02 | CACTA-like transposase family |

| AT4G09480b | AT4G09480 | 12.7 | 1.00E-05 | Copia-like retrotransposon family |

| AT2G20460b | AT2G20460 | 6.6 | 3.00E-04 | Copia-like retrotransposon family |

| AT4G09540b | AT4G09540 | 6.1 | 2.97E-02 | Copia-like retrotransposon family |

| AT2G11140 | AT2G11140 | 5.7 | 4.85E-02 | Copia-like retrotransposon family |

| AT2G26630b | AT2G26630 | 8.6 | 7.00E-04 | Transposase IS4 family protein |

| AT1G42705b | AT1G42705 | 6.5 | 2.24E-02 | hAT-like transposase family |

| AT2G04460b | AT2G04460 | 40.8 | 1.00E-04 | Similar to pol polyprotein |

| AT1G47860 | AT1G47860 | 3.8 | 3.11E-02 | Non-LTR retrotransposon family |

| AT4G03790 | AT4G03790 | 3 | 1.60E-03 | Gypsy-like retrotransposon family |

| Genes related to stress | ||||

| TET9b | AT4G30430 | 8.1 | 1.00E-04 | Involved in aging |

| AT3G10200b | AT3G10200 | 6.6 | 3.50E-02 | Dehydration-responsive protein-related |

| AT2G29500b | AT2G29500 | 3.3 | 1.00E-05 | Class I small heat shock protein (HSP17.6B-CI) |

| SRG1b | AT1G17020 | 3.1 | 2.64E-02 | Senescence-related gene |

| ATCLH1b | AT1G19670 | 2.3 | 2.74E-02 | Chlorophyll degradation and response to stress |

| ADR1b | AT1G33560 | 2.3 | 1.00E-05 | Encodes a NBS-LRR disease resistance protein |

| AOC1b | AT3G25760 | 2.2 | 3.15E-02 | JA biosynthesis |

| ATCXE18 | AT5G23530 | 2.2 | 1.98E-02 | Similar to ATGID1C/GID1C |

| JAZ7b | AT2G34600 | −5.1 | 1.20E-03 | JA signaling |

| STZb | AT1G27730 | −3.9 | 9.00E-04 | Salt tolerance |

| RHL41b | AT5G59820 | −3.2 | 1.41E-02 | Cold stress |

| CBF1 | AT4G25490 | −2.7 | 1.40E-03 | Cold stress |

| CBF2 | AT4G25470 | −3.1 | 1.00E-04 | Cold stress |

| Transcription factors | ||||

| AT1G59930b | AT1G59930 | 17.3 | 1.00E-05 | MADS box protein |

| AGL37b | AT1G65330 | 13.3 | 1.00E-05 | Type 1 MADS box protein |

| AT2G36080b | AT2G36080 | 3.9 | 3.17E-02 | B3 DNA-binding domain transcription factor |

| AT3G53370b | AT3G53370 | 3.5 | 1.00E-04 | DNA-binding S1FA family protein |

| AT5G66980b | AT5G66980 | 3.3 | 1.00E-05 | Transcriptional factor B3 family protein |

| AT5G25810b | AT5G25810 | 2.4 | 2.06E-02 | ERF/AP2 transcription factor family |

| AT1G74930b | AT1G74930 | −7.2 | 1.00E-05 | A member of the DREB subfamily A-5 of ERF/AP2 |

| AT5G61600b | AT5G61600 | −4 | 4.00E-04 | Encodes a member of the ERF |

| AT5G51190b | AT5G51190 | −3 | 2.70E-02 | Encodes a member of the ERF |

Expression fold increase or decrease in HDA6-RNAi (cs24039) relative to the Ws wild type.

Confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR.

Figure 7.

Validation of the DNA microarray data. qRT-PCR analysis of the gene expression involved in flowering (A), gene silencing (B), stress (C), and transposons (D) is shown. Total RNA was isolated from Ws, HDA6-RNAi (cs24039), Col, and axe1-5 plants grown in SD conditions. The values shown are relative fold changes compared with Col (for axe1-5) or Ws (for HDA6-RNAi) with sd. * The fold change was higher than 20.

HDA6 is implicated in gene silencing and stress responses (Aufsatz et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008). Therefore, we investigated the expression of genes related to gene silencing and stress responses by qRT-PCR. Seven genes related to gene silencing were analyzed, and all of them showed a correlation between qRT-PCR and microarray data (Fig. 7B). It is interesting that the expression of two genes encoding AGO proteins, AGO5 and AGO3, was up-regulated. Ten genes involved in stress responses analyzed by qRT-PCR were also shown to be consistent with the microarray data (Fig. 7C). In addition, a subset of transposons was up-regulated in axe1-5 and HDA6-RNAi plants (Table I), supporting a role of HDA6 in maintaining the stability of transposons (Aufsatz et al., 2007). Nine transposons analyzed all showed a correlation between qRT-PCR and microarray data (Fig. 6D).

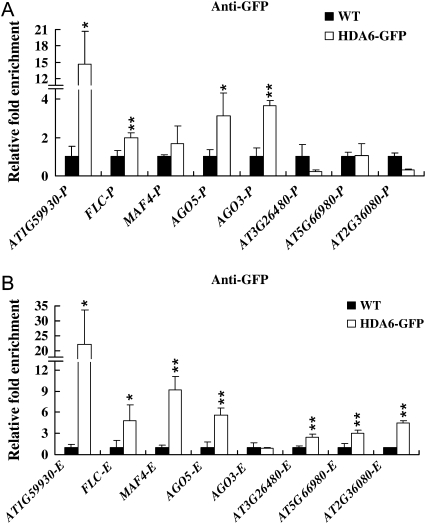

Most of the genes identified by DNA microarrays may not be the direct target genes regulated by HDA6. In order to identify the direct targets of HDA6, Arabidopsis plants overexpressing HDA6-GFP (35S:HDA6-GFP) were used to perform the ChIP assay. Overexpressing 35S:HDA6-GFP in the axe1-5 mutant can complement the delayed-flowering phenotype, suggesting that the HDA6-GFP fusion protein is functional. Real-time PCR was used to determine whether promoters and regions surrounding the translational starting sites of selected genes were enriched by ChIP with an anti-GFP antibody. Among 47 genes tested, HDA6 was recruited to the promoters and/or regions surrounding the translational starting sites of eight genes, AT1G59930, FLC, MAF4, AGO5, AGO3, AT3G26480, AT5G66980, and AT2G36080 (Fig. 8), suggesting that these genes probably are the direct targets of HDA6.

Figure 8.

Target genes of HDA6 identified by ChIP followed by real-time PCR analysis. Transgenic plants expressing HDA6-GFP were subjected to ChIP analysis using an anti-GFP antibody. Wild-type (WT) plants were used as negative controls. The relative fold enrichment of a target in the promoter (A) and transcription start site (B) was calculated by dividing the amount of DNA immunoprecipitated from HDA6-GFP transgenic plants by that from the negative control plants and compared with input DNA. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

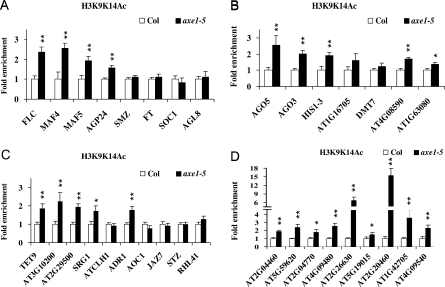

Genes Up-Regulated in axe1-5 Plants Are Hyperacetylated

We further investigated histone acetylation levels of the genes affected by HDA6 in the axe1-5 mutant by ChIP assay. The relative enrichment of histone H3 acetylation was determined by real-time PCR using primers specific for the proximal promoters (within 500 bp upstream of the translation starting sites) and the first exons surrounding the translation start sites of individual genes. Among those up-regulated genes related to flowering, the hyperacetylation of the first exons was found in FLC, MAF4, MAF5, and AGP24 but not in SMZ in axe1-5 mutants (Fig. 9A). Similar acetylation patterns were also observed in the promoter regions (data not shown). In contrast, there was no significant difference between Col wild-type and axe1-5 mutant plants in those genes that were down-regulated, such as FT, SOC1, and AGL8 (Fig. 9A). The H3K4 trimethylation levels of flowering-related genes were also analyzed. Increased H3K4 trimethylation was found in AGL37, FLC, MAF4, MAF5, and AGP24 in axe1-5 as well as fld-6 and axe1-5/fld-6 plants (Supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that there is a correlation between histone H3 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation. These data indicate that HDA6 and FLD may affect similar genes involved in flowering.

Figure 9.

Histone acetylation of genes up-regulated in axe1-5 plants. The relative levels of acetyl H3K9K14 of genes involved in flowering (A), gene silencing (B), stress (C), and transposons (D) in Col and axe1-5 were analyzed by ChIP. The immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by real-time PCR and subsequently normalized to an internal control (ACTIN2). The fold enrichment of axe1-5 over Col is shown, and the values shown are means ± sd. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

We also investigated the histone acetylation of genes related to gene silencing and stress responses as well as transposons by ChIP assay. All of the up-regulated genes related to gene silencing showed hyperacetylation of histone H3 in axe1-5 (Fig. 9B). Five up-regulated genes involved in stress responses, TET9, SRG1, ADR1, AT2G29500, and AT3G10200, showed increased histone H3 acetylation in axe1-5 plants (Fig. 9C). ChIP assay also shows hyperacetylation of histone H3 in the transposons up-regulated in axe1-5 (Fig. 9D). These data suggest that the up-regulation of gene expression in axe1-5 mutants was associated with histone hyperacetylation.

DISCUSSION

Molecular genetic studies on the mechanism of flowering in Arabidopsis have revealed four major flowering pathways: the photoperiod, autonomous, vernalization, and gibberellin pathways (Boss et al., 2004; Henderson and Dean, 2004). The Arabidopsis autonomous floral promotion pathway promotes flowering independently of the photoperiod and vernalization pathways by repressing FLC (Michaels and Amasino, 2001). The flowering of axe1-5 plants was delayed in both LD and SD conditions, and the delay in flowering time of axe1-5 was completely corrected by vernalization, suggesting that HDA6 is involved in the autonomous pathway of flowering (Wu et al., 2008). We observed that FLC was up-regulated and hyperacetylated in axe1-5 plants. Furthermore, the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 mutants was suppressed by an flc null mutant. These data suggest that HDA6 is involved in flowering by regulating FLC expression. In addition to FLC, MAF4 and MAF5 were also up-regulated and hyperacetylated in axe1-5 plants. By using microarray analysis, two additional MADS box genes, AGL37 and AT5G59930, were also identified to be up-regulated and hyperacetylated in axe1-5 plants. Since HDA6 is a trichostain A-sensitive histone deacetylase capable of removing acetyl groups from multiple Lys residues of histones (Earley et al., 2006, 2010), HDA6 may repress FLC as well as other MADS box genes through deacetylating their chromatin. ChIP analysis indicated that HDA6 bound directly to the promoters of FLC, MAF4, and AT5G59930, suggesting that they may be the direct targets of HDA6. In addition to the increase of FLC expression, a portion of the late-flowering phenotype of axe1-5 mutants could be due to other floral repressors, because axe1-5/flc-3 double-mutant plants flowered later than flc-3 single mutant plants.

A large number of mutants have been identified to be involved in the autonomous pathway (Michaels, 2009). In two autonomous mutants, fld and fve, FLC displays hyperacetylation of histone H3 and H4, indicating that FVE and FLD are required to deacetylate FLC chromatin and repress its expression (He et al., 2003; Ausín et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004). FVE encodes the nuclear WD-repeat protein, AtMSI4, a retinoblastoma-associated protein that functions in the histone deacetylase complexes (Ausín et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004). Hence, FVE is likely to act in a HDAC complex to repress FLC expression (Ausín et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004). FLD encodes a plant homolog of mammalian LSD1 and is involved in the H3K4 demethylation and deacetylation of FLC chromatin (Jiang et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007). axe1-5 and fld-6 mutants displayed increased levels of H3 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation in FLC, MAF4, and MAF5, suggesting that both HDA6 and FLD are required for removing H3 acetylation and H3K4 methylation. Compared with the single mutants, the axe1-5/fld-6 double mutant shows additive effects on FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 expression as well as flowering time. However, H3K9K14 acetylation and H3K4 trimethylation levels in the double mutant are similar to those in the single mutants. These data suggest that the enhanced FLC expression and delayed flowering time in the double mutant may be caused by factors other than H3K9K14Ac and H2K4Me3.

Although cross talk between histone deacetylation and demethylation has previously been suggested to modulate gene expression in mammalian cells (Shi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2006), the direct association of a HDAC with a histone demethylase has not been reported. In this study, we found that HDA6 physically associates with FLD in vitro and in vivo, indicating that these two proteins act in the same protein complex. BiFC assays indicate that the interaction site of HDA6 and FLD is at the nuclear periphery. The peripheral zone of the nucleus is the area that has been implicated in the regulation of gene expression, especially gene silencing (Deniaud and Bickmore, 2009). The mammalian histone demethylase, LSD1, is an integral component of histone deacetylase corepressor complexes, in which HDACs and LSD1 may cooperate to remove activating acetyl and methyl histone modifications (Shi et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2006). HDAC inhibitors can diminish histone demethylation activity, whereas the abrogation of LSD1 activity by mutations can decrease deacetylation activity (Lee et al., 2006), suggesting that the enzymatic activities of HDACs and LSD1 are closely linked. Further research is required to determine whether there is a synergistic interplay between histone demethylase and deacetylase activities in plants.

Vernalization also promotes flowering by repressing FLC expression (Amasino, 2004; Schmitz and Amasino, 2007). The levels of acetylation of histone H3 at Lys-9 and Lys-14 are reduced during vernalization, followed by an increase in methylation of histone H3 at Lys-9 and Lys-27 (Bastow et al., 2004; Sung and Amasino, 2004). During prolonged cold, VRN5 and VIN3 form a heterodimer necessary for establishing the vernalization-induced chromatin modifications, including histone deacetylation and H3 K27 trimethylation, required for the epigenetic silencing of FLC (Greb et al., 2007; De Lucia et al., 2008). VRN5 and VIN3 are members of PHD finger-containing proteins, which are often found in various components of chromatin-remodeling complexes, including HDACs (Aasland et al., 1995; Xia et al., 2003). These observations suggest that HDACs also play an important role in the epigenetic modification directed by vernalization. Since axe1-5 mutants exhibit a normal vernalization response, HDA6-mediated deacetylation is not required for vernalization (Wu et al., 2008). A recent study suggests that vernalization-mediated FLC repression is via a novel pathway involving the SIR2 class of HDACs, SRT1 and SRT2 (Bond et al., 2009).

axe1 and other mutant alleles of hda6, rts1 and sil1, were isolated based on deregulated expression of transgenes (Murfett et al., 2001; Aufsatz et al., 2002; Probst et al., 2004). Mutations in HDA6 result in the loss of transcriptional silencing from several repetitive transgenic and endogenous templates. Genome-wide gene expression analysis using the Affymetrix GeneChip indicates that down-regulation of HDA6 affected genes involved in a variety of biological processes. In addition to genes involved in flowering, genes involved in gene silencing and stress responses were also affected in hda6 mutants, supporting multiple functions of HDA6 (Aufsatz et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010; Earley et al., 2010). We found that the expression of two genes encoding AGO proteins, AGO5 and AGO3, was up-regulated in hda6 mutants. ChIP analysis indicated that HDA6 bound directly to the promoters of AGO5 and AGO3, suggesting that they may be the direct targets of HDA6. The AGO proteins are involved in RNA-silencing processes that also involve 21- to 25-nucleotide short RNAs cleaved from double-stranded RNAs by the RNaseIII enzyme Dicer (Baumberger and Baulcombe, 2005). It is suggested that HDA6 plays an important role in RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation (Aufsatz et al., 2007; Earley et al., 2010). Up-regulation of AGO5 and AGO3 in hda6 mutants suggests that HDA6 may be involved in RNAi-mediated gene silencing by regulating the expression of AGO-like genes.

A subset of transposons was up-regulated in HDA6-RNAi and axe1-5 plants. Similarly, down-regulation of a SIR2-class HDAC, OsSRT1, also results in transposon activation in OsSRT1-RNAi rice (Oryza sativa) plants (Huang et al., 2007). These results suggest that HDA6 and other HDACs are required to maintain the stability of transposable elements. Besides histone modifications, DNA methylation is also associated with gene-silencing mechanisms in eukaryotic organisms. Recent studies suggest that HDA6 is required for maintaining cytosine methylation (Aufsatz et al., 2007; Earley et al., 2010). Based on genomic transcriptional analysis, we demonstrate that HDA6 regulates transposon expression. In addition, up-regulation of transposons was associated with a high level of chromatin H3 acetylation in the axe1-5 mutant, suggesting that HDA6 regulates transposon expression by chromatin deacetylation. These results suggest that HDA6 plays an important role in the interplay between histone deacetylation and DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was grown in growth chambers under LD (16 h of light/8 h of dark) or SD (8 h of light/16 h of dark) conditions. The hda6 mutant line axe1-5, the HDA6 RNAi line cs24039, and the FLD T-DNA insertion mutant fld-6 (SAIL_642_C05.v2) were used in this study. cs24039 is in the Ws background, whereas axe1-5 and fld-6 are in the Col background. axe1-5 was originally isolated based on deregulated expression of auxin-responsive transgenes (Murfett et al., 2001) and was outcrossed into the Col wild type three times.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Arabidopsis leaves (0.1–0.2 g) were ground with liquid nitrogen in a mortar and pestle and mixed with 1 mL of Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) to isolate total RNA. One microgram of total RNA was used for the first-strand cDNA synthesis after incubation at 65°C for 10 min. cDNA was synthesized in a volume of 20 μL that contained the Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase buffer (Promega), 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1.5 μm poly(dT) primer, 0.5 mm deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates, 25 units of RNasin RNase inhibitor, and 200 units of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase at 37°C for 1 h.

cDNAs obtained from RT were used as templates to run real-time PCR. The following components were added to a reaction tube: 9 μL of iQ SYBR Green Supermix solution (Bio-Rad), 1 μL of 5 μm specific primers, and 8 μL of the diluted template. Thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s, with a melting curve detected at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and detection of the denature time from 55°C to 95°C. Each sample was quantified at least in triplicate and normalized using Ubiquitin10 as an internal control. The gene-specific primer pairs for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Microarray Analysis

Genome-wide gene expression analysis using the Affymetrix Arabidopsis GeneChip was performed using Ws and HDA6-RNAi (cs24039) plants. Total RNA was isolated from leaves of 3-week-old plants growing under SD conditions. cDNA synthesis, labeling, hybridization, and scanning of the DNA chips were carried out at the National Taiwan University Center for Genomic Medicine. Microarray experiments were performed in triplicate biological samples. Microarray Analysis Suite 5.0 (Affymetrix) was used for analysis of the microarray data. The software was also used to determine whether the expression of each gene is present or absent (absolute call) and whether the fold change value represents a genuine change in expression (difference call). The statistics program National Institute of Aging Array analysis (Sharov et al., 2005) was used to identify statistically significant differentially expressed genes.

ChIP Assay

The ChIP assay was carried out as described (Gendrel et al., 2005). Chromatin extracts were prepared from young leaves treated with formaldehyde. The chromatin was sheared to an average length of 500 bp by sonication and immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies, including anti-acetylated histone H3K9K14 (catalogue no. 06-599; Millipore) and anti-trimethyl histone H3K4 (catalogue no. 04-745; Millipore). The DNA cross-linked to immunoprecipitated proteins was analyzed by real-time PCR. Relative enrichments of various regions of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 over Col were calculated after normalization to ACTIN2. Each of the immunoprecipitations was replicated three times, and each sample was quantified at least in triplicate. The primers used for real-time PCR analysis in ChIP assays are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assays

Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed according to the instructions for the Matchmaker GAL4-based two-hybrid system 3 (Clontech). Different regions of HDA6 and FLD cDNA fragments were subcloned into pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors. All constructs were transformed into yeast strain AH109 by the lithium acetate method, and yeast cells were grown on a minimal medium/-Leu-Trp according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech). Transformed colonies were plated onto a minimal medium/-Leu/Trp-His/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside containing 0.5 mm 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole to test for possible interactions between FLD and HDA6.

BiFC Assays

To generate the constructs for BiFC, full-length coding sequences of HDA6 and FLD were PCR amplified. The PCR products were subcloned into the pENTR/SD/D-TOPO or pCR8/GW/TOPO vector and then recombined into the pEarleyGate201-YN and pEarleyGate202-YC vectors (Lu et al., 2010). The resulting constructs were used for transient assays by polyethylene glycol transfection of Arabidopsis protoplasts (Yoo et al., 2007). Transfected cells were imaged using the TCS SP5 Confocal Spectral Microscope Imaging System (Leica).

In Vitro Pull-Down Assay

The pull-down assay was performed as described previously (Yang et al., 2008) with some modifications. For GST pull-down, GST and GST-HDA6 recombinant proteins were incubated with 30 μL of GST resin in a binding buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 0.25% Triton X-100, and 35 mm β-mercaptoethanol) for 2 h at 4°C, the binding reaction was washed three times with the binding buffer, and then the FLD-His recombinant protein was added and incubated for an additional 2 h at 4°C. For His pull-down, His and FLD-His recombinant proteins were incubated with 30 μL of His resin in a phosphate buffer (10 mm Na2HPO4, 10 mm NaH2PO4, 500 mm NaCl, and 10 mm imidazole) for 2 h at 4°C, the binding reaction was washed three times with the phosphate buffer, and then GST-HDA6 recombinant protein was added and incubated for an additional 2 h at 4°C. After extensive washing (at least eight times), the pulled down proteins were eluted by boiling, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and detected by western blotting using an anti-His or anti-GST antibody.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

Coimmunoprecipitation assay was performed as described by Yang et al. (2008). Two days after infiltration, tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves were harvested and ground in liquid nitrogen. Proteins were extracted in an extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 20% glycerol, and 1% Igepal CA-630 [Sigma-Aldrich]) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 14,000g for 20 min. The supernatant was incubated with 6 μg of anti-Myc antibody (Sigma) for 4 h at 4°C, then 50 μL of protein A agarose beads (Millipore) was added. After 2 h of incubation at 4°C, the beads were centrifuged and washed six times with a washing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 10% glycerol, and 1% CA-630). Proteins were eluted with 40 μL of 2.5× sample buffer and analyzed by western blotting using anti-GFP and anti-Myc antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. BiFC in Arabidopsis protoplasts showing interaction between HDA6 and FLD in living cells.

Supplemental Figure S2. Classification of genes affected by HDA6 in the DNA microarray analysis.

Supplemental Figure S3. Histone H3K4 trimethylation of flowering-related genes in axe1-5, fld-6, and axe1-5/fld-6 plants.

Supplemental Table S1. Gene-specific primer pairs for qRT-PCR.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used for real-time PCR analysis in ChIP assays.

Supplemental Table S3. Genes up-regulated in the HDA6-RNAi line compared with the wild type.

Supplemental Table S4. Genes down-regulated in the HDA6-RNAi line compared with the wild type.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jun-Yi Yang for help with the coimmunoprecipitation assay and Dr. Rick M. Amasino for providing flc-3 seeds.

References

- Aasland R, Gibson TJ, Stewart AF. (1995) The PHD finger: implications for chromatin-mediated transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 56–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino R. (2004) Take a cold flower. Nat Genet 36: 111–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L, Iyer L M. (2002) The SWIRM domain: a conserved module found in chromosomal proteins points to novel chromatin-modifying activities. Genome Biol 3: research0039.1–research0039.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufsatz W, Mette MF, van der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. (2002) HDA6, a putative histone deacetylase needed to enhance DNA methylation induced by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J 21: 6832–6841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aufsatz W, Stoiber T, Rakic B, Naumann K. (2007) Arabidopsis histone deacetylase 6: a green link to RNA silencing. Oncogene 26: 5477–5488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausín I, Alonso-Blanco C, Jarillo JA, Ruiz-García L, Martínez-Zapater JM. (2004) Regulation of flowering time by FVE, a retinoblastoma-associated protein. Nat Genet 36: 162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastow R, Mylne JS, Lister C, Lippman Z, Martienssen RA, Dean C. (2004) Vernalization requires epigenetic silencing of FLC by histone methylation. Nature 427: 164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N, Baulcombe DC. (2005) Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1 is an RNA Slicer that selectively recruits microRNAs and short interfering RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11928–11933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. (2007) The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447: 407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DM, Dennis ES, Pogson BJ, Finnegan EJ. (2009) Histone acetylation, VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3, FLOWERING LOCUS C, and the vernalization response. Mol Plant 2: 724–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Bastow RM, Mylne JS, Dean C. (2004) Multiple pathways in the decision to flower: enabling, promoting, and resetting. Plant Cell (Suppl) 16: S18–S31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LT, Luo M, Wang YY, Wu K. (2010) Involvement of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 in ABA and salt stress response. J Exp Bot 61: 3345–3353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Tian L. (2007) Roles of dynamic and reversible histone acetylation in plant development and polyploidy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1769: 295–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia F, Crevillen P, Jones AM, Greb T, Dean C. (2008) A PHD-polycomb repressive complex 2 triggers the epigenetic silencing of FLC during vernalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 16831–16836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Liu C, Pei Y, Deng X, Niu L, Cao X. (2007) Involvement of the histone acetyltransferase AtHAC1 in the regulation of flowering time via repression of FLOWERING LOCUS C in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 1660–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniaud E, Bickmore WA. (2009) Transcription and the nuclear periphery: edge of darkness? Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 187–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. (2007) Epigenetic regulation of flowering. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10: 520–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley K, Lawrence RJ, Pontes O, Reuther R, Enciso AJ, Silva M, Neves N, Gross M, Viegas W, Pikaard CS. (2006) Erasure of histone acetylation by Arabidopsis HDA6 mediates large-scale gene silencing in nucleolar dominance. Genes Dev 20: 1283–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Pontvianne F, Wierzbicki AT, Blevins T, Tucker S, Costa-Nunes P, Pontes O, Pikaard CS. (2010) Mechanisms of HDA6-mediated rRNA gene silencing: suppression of intergenic Pol II transcription and differential effects on maintenance versus siRNA-directed cytosine methylation. Genes Dev 24: 1119–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel AV, Lippman Z, Martienssen R, Colot V. (2005) Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat Methods 2: 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greb T, Mylne JS, Crevillen P, Geraldo N, An H, Gendall AR, Dean C. (2007) The PHD finger protein VRN5 functions in the epigenetic silencing of Arabidopsis FLC. Curr Biol 17: 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Amasino RM. (2005) Role of chromatin modification in flowering-time control. Trends Plant Sci 10: 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Michaels SD, Amasino RM. (2003) Regulation of flowering time by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. Science 302: 1751–1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell CA, Wood CC, Robertson M, James Peacock W, Dennis ES. (2006) The Arabidopsis FLC protein interacts directly in vivo with SOC1 and FT chromatin and is part of a high-molecular-weight protein complex. Plant J 46: 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Dean C. (2004) Control of Arabidopsis flowering: the chill before the bloom. Development 131: 3829–3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Sun Q, Qin F, Li C, Zhao Y, Zhou DX. (2007) Down-regulation of a SILENT INFORMATION REGULATOR2-related histone deacetylase gene, OsSRT1, induces DNA fragmentation and cell death in rice. Plant Physiol 144: 1508–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Yang W, He Y, Amasino RM. (2007) Arabidopsis relatives of the human lysine-specific Demethylase1 repress the expression of FWA and FLOWERING LOCUS C and thus promote the floral transition. Plant Cell 19: 2975–2987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JB, Jin YH, Lee J, Miura K, Yoo CY, Kim WY, Van Oosten M, Hyun Y, Somers DE, Lee I, et al. (2008) The SUMO E3 ligase, AtSIZ1, regulates flowering by controlling a salicylic acid-mediated floral promotion pathway and through effects on FLC chromatin structure. Plant J 53: 530–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Hyun Y, Park JY, Park MJ, Park MK, Kim MD, Kim HJ, Lee MH, Moon J, Lee I, et al. (2004) A genetic link between cold responses and flowering time through FVE in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet 36: 167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Wynder C, Bochar DA, Hakimi MA, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. (2006) Functional interplay between histone demethylase and deacetylase enzymes. Mol Cell Biol 26: 6395–6402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Quesada V, Crevillén P, Bäurle I, Swiezewski S, Dean C. (2007) The Arabidopsis RNA-binding protein FCA requires a lysine-specific demethylase 1 homolog to downregulate FLC. Mol Cell 28: 398–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Tang X, Tian G, Wang F, Liu K, Nguyen V, Kohalmi SE, Keller WA, Tsang EW, Harada JJ, et al. (2010) Arabidopsis homolog of the yeast TREX-2 mRNA export complex: components and anchoring nucleoporin. Plant J 61: 259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD. (2009) Flowering time regulation produces much fruit. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels SD, Amasino RM. (2001) Loss of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity eliminates the late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and autonomous pathway mutations but not responsiveness to vernalization. Plant Cell 13: 935–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murfett J, Wang XJ, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. (2001) Identification of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 mutants that affect transgene expression. Plant Cell 13: 1047–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R, Müller A, Napoli CA, Selinger DA, Pikaard CS, Richards EJ, Bender J, Mount DW, Jorgensen RA. (2002) Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 5036–5055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst AV, Fagard M, Proux F, Mourrain P, Boutet S, Earley K, Lawrence RJ, Pikaard CS, Murfett J, Furner I, et al. (2004) Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 is required for maintenance of transcriptional gene silencing and determines nuclear organization of rDNA repeats. Plant Cell 16: 1021–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C, Zhang Q, Li S, Zeng L, Walsh MJ, Zhou MM. (2005) Structure and chromosomal DNA binding of the SWIRM domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 1078–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz RJ, Amasino RM. (2007) Vernalization: a model for investigating epigenetics and eukaryotic gene regulation in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1769: 269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharov AA, Dudekula DB, Ko MS. (2005) A Web-based tool for principal component and significance analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 21: 2548–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi YJ, Matson C, Lan F, Iwase S, Baba T, Shi Y. (2005) Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol Cell 19: 857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung S, Amasino RM. (2004) Vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana is mediated by the PHD finger protein VIN3. Nature 427: 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Zhang L, Zhou C, Yu CW, Chaikam V. (2008) HDA6 is required for jasmonate response, senescence and flowering in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 59: 225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia ZB, Anderson M, Diaz MO, Zeleznik-Le NJ. (2003) MLL repression domain interacts with histone deacetylases, the polycomb group proteins HPC2 and BMI-1, and the corepressor C-terminal-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 8342–8347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JY, Iwasaki M, Machida C, Machida Y, Zhou X, Chua NH. (2008) BetaC1, the pathogenicity factor of TYLCCNV, interacts with AS1 to alter leaf development and suppress selective jasmonic acid responses. Genes Dev 22: 2564–2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. (2007) Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat Protoc 2: 1565–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]