Abstract

The membrane-spanning protein PIC1 (for permease in chloroplasts 1) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) was previously described to mediate iron transport across the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts. The albino phenotype of pic1 knockout mutants was reminiscent of iron-deficiency symptoms and characterized by severely impaired plastid development and plant growth. In addition, plants lacking PIC1 showed a striking increase in chloroplast ferritin clusters, which function in protection from oxidative stress by sequestering highly reactive free iron in their spherical protein shell. In contrast, PIC1-overexpressing lines (PIC1ox) in this study rather resembled ferritin loss-of-function plants. PIC1ox plants suffered from oxidative stress and leaf chlorosis, most likely originating from iron overload in chloroplasts. Later during growth, plants were characterized by reduced biomass as well as severely defective flower and seed development. As a result of PIC1 protein increase in the inner envelope membrane of plastids, flower tissue showed elevated levels of iron, while the content of other transition metals (copper, zinc, manganese) remained unchanged. Seeds, however, specifically revealed iron deficiency, suggesting that PIC1 overexpression sequestered iron in flower plastids, thereby becoming unavailable for seed iron loading. In addition, expression of genes associated with metal transport and homeostasis as well as photosynthesis was deregulated in PIC1ox plants. Thus, PIC1 function in plastid iron transport is closely linked to ferritin and plastid iron homeostasis. In consequence, PIC1 is crucial for balancing plant iron metabolism in general, thereby regulating plant growth and in particular fruit development.

Chloroplasts originated about three billion years ago from endosymbiosis of an ancestor of today’s cyanobacteria with a mitochondria-containing host cell (Moreira et al., 2000; Palmer, 2000). During evolution, chloroplasts in higher plants established as the site of photosynthesis and thus became the basis for all life dependent on oxygen and carbohydrate supply. To fulfill this task, plastid organelles are loaded with the transition metal iron, which due to its potential for valency changes is essential for photosynthetic electron transport (Raven et al., 1999). In consequence, chloroplasts represent the iron-richest system in plant cells (Terry and Low, 1982). However, the improvement of oxygenic photosynthesis in turn required adaptation of processes related to iron transport and homeostasis. (1) Oxidation of soluble ferrous iron (Fe2+) to almost insoluble ferric iron (Fe3+) turned the most abundant metal in the earth’s crust into a limiting factor (Morel and Price, 2003). Thus, higher plants developed certain strategies for iron acquisition from the surrounding soil (for overview, see Palmer and Guerinot, 2009). (2) Metal-catalyzed generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS; Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1992) causes oxidative damage and requires tight control of transport, storage, and cofactor assembly of metal ions (Kosman, 2010). Studies on plants with abnormally high iron levels, therefore, show increased ROS levels and the promotion of oxidative stress responses (Kampfenkel et al., 1995; Caro and Puntarulo, 1996; Pekker et al., 2002). This is most acute in iron-rich chloroplasts, where radicals and transition metals are side by side and production of ROS-like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a usual feature of photosynthetic electron transport (Asada, 1999; Mubarakshina et al., 2010). Thus, on the one hand, when bound in FeS cluster or heme proteins, chloroplast-intrinsic iron is a prerequisite for photoautotrophic life, but on the other hand, it is toxic when present in its highly reactive, hydroxyl radical-generating, free ionic forms. In consequence, plastid iron homeostasis and transport has to be tightly controlled and is crucial throughout plant development and growth.

Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake into cells of dicotyledonous plants are best studied in the plasma membrane of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) roots, where the ferric-chelate reductase oxidase FRO2 (Robinson et al., 1999) reduces soil ferric iron prior to Fe2+ uptake into epidermal cells by the divalent metal transporter IRT1 (for iron-regulated transporter1; Vert et al., 2002, for overview, see Palmer and Guerinot, 2009). In contrast, current knowledge on iron transport across the two envelope membranes of plastids is still scarce. Uptake experiments with isolated chloroplasts and purified inner membrane vesicles described plastid Fe(III)-chelate transport (Bughio et al., 1997) and Fe2+ uptake across the inner envelope (Shingles et al., 2001, 2002). Localization of FRO7 (for ferric-chelate reductase oxidase7) in envelope membranes (Jeong et al., 2008) identified one component of the general iron transport pathway. Because fro7 loss-of-function mutants have less iron in chloroplasts and show chlorosis under iron-limiting conditions, FRO7 most likely plays a role in plastid iron uptake. Only recently, MAR1/IREG3 (for multiple antibiotic resistance1/iron-regulated protein3) was described as a plastid member of the ferroportin/IREG transporter family (Conte et al., 2009). Although MAR1/IREG3 specifically imports aminoglycoside antibiotics, due to sequence similarity to the metal transporters IREG1 and IREG2 (Schaaf et al., 2006; Morrissey et al., 2009) and the fact that MAR1 overexpression is causing leaf chlorosis that can be rescued by iron, the authors suggest that MAR1/IREG3 functions naturally in the uptake of the iron-chelating polyamine nicotianamine (NA) into chloroplasts (Conte et al., 2009; Conte and Lloyd, 2010).

With PIC1 (for permease in chloroplasts 1), we previously identified the first molecular component of the plastid iron-transport pathway in the inner envelope membrane (Duy et al., 2007). PIC1 was able to complement the growth of iron uptake-deficient yeast by mediating iron accumulation within cells. Besides their severe dwarf, albino phenotype that resembled iron-deficiency symptoms in plants, the most striking feature of pic1 knockout mutants was the accumulation of ferritin protein clusters. Plastid-localized ferritins represent the central component for balancing iron homeostasis, because they precipitate and store free iron in their oligomeric protein shell and thus withdraw this highly reactive metal from intracellular generation of ROS (for overview, see Briat et al., 2010). By generating plant lines overexpressing the iron permease PIC1, we here provide additional evidence that the function of PIC1 in the inner envelope of chloroplasts (iron transport) is tightly linked to ferritin (iron storage) and iron homeostasis. Thus, both plastid proteins represent key players in regulating iron transport and metabolism as well as metal-generated oxidative stress. Furthermore, PIC1 overproduction raised iron levels in chloroplasts and specifically changed iron content in flowers (increase) and seeds (decrease). Therefore, by mediating iron uptake and sequestering processes in plastids, PIC1 is crucial for plant growth and development in general and in particular for fruit maturation.

RESULTS

Generation of Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing PIC1

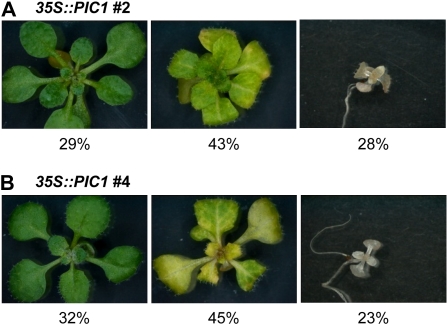

To obtain stable plant lines overexpressing PIC1, the coding sequence of the chloroplast-targeted PIC1 precursor protein (Duy et al., 2007) under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35S::PIC1) was introduced into ecotype Columbia (Col-0) wild-type Arabidopsis plants. Eight independent T1 lines that inherited the 35S::PIC1 construct and produced viable seeds in the T2 generation were generated. Two of these lines (lines 2 and 4) showed identical phenotypes that segregated in a Mendelian fashion (Fig. 1). About 25% of the progeny was of wild-type appearance, 25% of the seedlings were dwarfed and albino, and the remaining 50% showed yellow-green, chlorotic leaves, visible after 2 to 3 weeks of growth. PCR genotyping confirmed that the green plants of lines 2 and 4 were wild type for PIC1, while the albino seedlings and the chlorotic plantlets both contained the 35S::PIC1 construct. Because the yellow-green progeny in all subsequent generations showed this phenotypic segregation pattern, we conclude that these plants are heterozygous for 35S::PIC1. In consequence, the dwarfed albino seedlings represent homozygous alleles for the 35S::PIC1 construct. Since all albino seedlings were nonviable, experiments were performed on the heterozygous chlorotic progeny of the independently derived 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic segregation of 35S::PIC1 plants. Plants of the 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4 were grown for 3 weeks on plates. Both lines segregated in a Mendelian fashion, producing progeny with green wild-type (left), chlorotic (middle), and albino (right) phenotypes. A, Of 123 plants analyzed in the T2 generation (35S::PIC1 line 2), 29% were of green wild-type appearance, 43% showed yellow-green leaves, and 28% were dwarfed albinos. B, From the 35S::PIC1 line 4, 97 plants in the T2 generation split into progeny of 32% green, 45% chlorotic, and 23% albino phenotype.

PIC1 RNA and Chloroplast-Intrinsic Protein Are Increased in 35S::PIC1 Lines

The 35S::PIC1 transgenic lines were analyzed for their PIC1 transcript and protein content by quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and immunoblot analysis, respectively (Fig. 2). Thereby, it became evident that 2-week-old, chlorotic seedlings of the heterozygous 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4 contained about 26 times more PIC1 mRNA than Col-0 (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Table S1). In all segregating wild-type plantlets as well as in seedlings of other 35S::PIC1 lines generated, PIC1 mRNA content was not significantly elevated. In contrast, in the lethal albino seedlings from lines 2 and 4, identified as homozygous for 35S::PIC1, 5- to 10-fold more PIC1 transcripts than in heterozygous chlorotic seedlings of the same mother plant were detected (data not shown), indicating a gene dosage-dependent effect of 35S::PIC1 overexpression. Since progeny of line 3 contained the 35S::PIC1 construct as verified by PCR genotyping but showed neither a yellow-green leaf phenotype nor a strong increase in PIC1 transcripts (2-fold; Fig. 2A; Supplemental Table S1), this line was used as a wild-type-like control in the following.

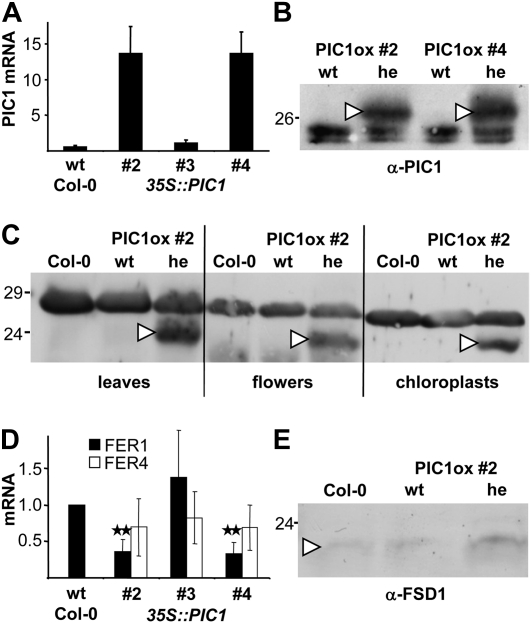

Figure 2.

35S::PIC1 lines overproduce PIC1 in chloroplasts and differentially express plastid iron homeostasis genes. A, Quantification of PIC1 transcripts by real-time RT-PCR in 14-d-old plantlets of Col-0 and 35S::PIC1 lines 2, 3, and 4. PIC1 mRNA (arbitrary units) was calculated relative to 10 molecules of actin 2/8 (n = 3 ± sd; for line 3, n = 2). For lines 2 and 4, only the chlorotic progeny heterozygous for 35S::PIC1 was used, while PIC1 mRNA in line 3 (wild-type-like control) was determined in all seedlings containing the 35::PIC1 construct. B, Immunoblot analysis of PIC1 in protein extracts (100 μg per lane) from 5-week-old rosette leaves of PIC1ox lines 2 and 4. The PIC1-specific signal at 26.5 kD was detectable only in the chlorotic progeny, heterozygous for 35S::PIC1 (he; arrowheads). In the segregating wild-type alleles (wt), α-PIC1 stained only background signal at about 24 kD. C, Immunoblot analysis of PIC1 in protein extracts from mature leaves, flowers, and isolated chloroplasts of PIC1ox line 2 and the Col-0 wild type. For leaves and flowers, 100 μg, and for chloroplasts, 12.5 μg, of protein was loaded per lane. Note that, in contrast to the blot in B, 4 m urea was used during gel separation, which shifted PIC1-specific signals in overexpressing plants of PIC1ox 2 he (arrowheads) to a size of about 24 kD and background in all tissues to 28 kD. D, Quantification of FER1 (black bars) and FER4 (white bars) transcripts by real-time RT-PCR as described in A. FER1 and FER4 mRNA (arbitrary units) was calculated relative to actin 2/8 and normalized to the amount in Col-0, which was set to 1.0. Asterisks indicate a significant reduction of FER1 transcripts (two-sample Student’s t test, P < 0.005) in PIC1ox 2 and 4 when compared with lines with PIC1 wild-type content (Col-0 and 35S::PIC1 line 3). E, Immunoblot analysis of the plastid-localized iron-superoxide dismutase FSD1 in protein extracts (12.5 μg per lane) from mature leaves of PIC1ox line 2 (he and wt) and the Col-0 wild type. Mature FSD1 proteins migrate at 22 kD.

To analyze PIC1 increase on the protein level, we subjected proteins from 5-week-old rosette leaves of the heterozygous 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4 to immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2B). In the extract from chlorotic leaves, the PIC1 antibody detected a strong signal at about 26.5 kD, corresponding to the predicted size of the overexpressed mature PIC1 construct. Note that due to the presence of a C-terminal tag of 4 kD, the overexpressed PIC1 protein is bigger than the endogenous mature form of PIC1 (22.5 kD; compare Duy et al., 2007). Because the same construct was able to complement the strong pic1 knockout phenotype, we deduce that the introduced PIC1 preprotein (construct of 36.2 kD) in the 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4 was properly processed by the chloroplast stromal peptidase and correctly inserted into the inner envelope membrane. Chloroplast-intrinsic PIC1 proteins were confirmed by immunoblotting on mature leaves, flowers, and purified chloroplasts (Fig. 2C). Again the PIC1 antibody specifically labeled proteins only in tissue of the heterozygous 35S::PIC1 line 2 but not in the corresponding wild types. Since PIC1-overexpressing (PIC1ox) signals in chloroplasts, leaf, and flower tissue were of the same size and comparable strong intensity, we conclude that the majority of the overexpressed PIC1 is present in the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts. Thus, the overproduced PIC1 proteins represent functional permeases. On proteins of leaves, flowers, and chloroplasts of Col-0 and the wild-type progeny, segregating from lines 2 and 4, however, α-PIC1 failed to recognize the endogenous mature PIC1 (Fig. 2, B and C). In general, to detect endogenous PIC1 signals via antiserum in wild-type plants, envelope preparations, which are strongly enriched for PIC1 proteins, have to be used (compare Duy et al., 2007). In summary, we conclude that the chlorotic phenotype of the independently derived heterozygous 35S::PIC1 lines 2 and 4 is due to highly increased levels of the iron-permease PIC1 in the inner envelope of chloroplasts. Therefore, we designate these lines as PIC1ox 2 and PIC1ox 4.

pic1 knockout mutants were characterized by increased transcript levels for FER1 and FER4 (for ferritin1 and 4), two isoforms of the iron-storage protein ferritin, resulting in the accumulation of ferritin clusters in plastids (Duy et al., 2007). To check whether we can detect a reciprocal behavior of ferritin gene expression in PIC1ox plants, we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis on 2-week-old seedlings of PIC1ox lines 2 and 4 as well as on PIC1 wild-type controls Col-0 and 35S::PIC1 line 3 (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Table S1). Thereby, we could show that FER1 but not FER4 transcripts were decreased by about 60% in PIC1ox lines, showing indeed down-regulation of the major leaf ferritin FER1 (Briat et al., 2010) in seedlings overexpressing PIC1. Furthermore, protein of the chloroplast-localized FSD1 (for Fe-dependent superoxide dismutase) increased in PIC1ox leaves (Fig. 2E), again showing a reciprocal behavior as in pic1 knockout plants (down-regulation; Duy et al., 2007). Thus, in PIC1ox plants, a noticeable regulation of plastid iron homeostasis genes is apparent (see “Discussion”).

The Phenotype of PIC1ox Plants Closely Resembles Mutants Lacking Ferritin and Is Most Likely Caused by Iron Overload in Chloroplasts

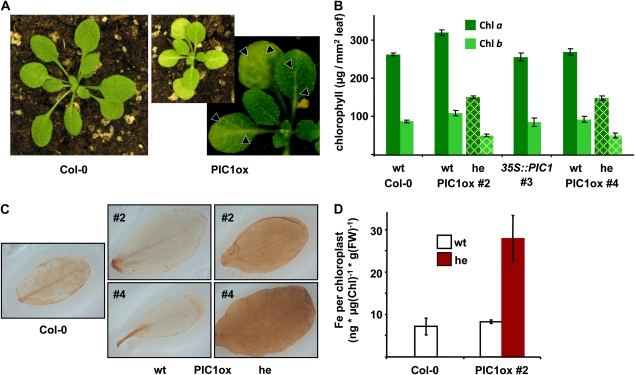

During further growth and development of PIC1ox plants, the yellow-green leaf phenotype became more pronounced. Chlorosis was first visible at the central vein, then spread over the entire surface in mature leaves (Fig. 3A). In 4-week-old leaves, this led to a decrease in chlorophyll a and b by 50% when compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Table S1). Staining of 6-week-old rosette leaves (Fig. 3C) revealed that chlorosis was accompanied by the production of H2O2, most likely originating from chloroplasts (Mubarakshina et al., 2010). Underlining the proposed function of PIC1 in iron uptake (Duy et al., 2007), we further found that mature chloroplasts of PIC1ox line 2 contained about 3-fold more iron than corresponding wild-type organelles (Fig. 3D; Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 3.

PIC1ox leaves are chlorotic and suffer from oxidative stress as well as iron overload in chloroplasts. A, A 3-week-old PIC1ox plant (line 4) in comparison with Col-0. Images of both plants are depicted with the same settings for magnification and brightness. At right is a closeup of PIC1ox leaves to highlight the development of chlorosis (arrowheads). B, Chlorophyll (Chl) content in rosette leaves of 4-week-old Col-0 and 35S::PIC1 lines 2, 3, and 4. Chlorophyll a (dark green) and chlorophyll b (light green) concentrations were determined in leaf discs of identical size (μg mm−2 leaf tissue; n = 5 ± sd). In the chlorotic PIC1ox lines 2 and 4 (he; yellow grid), chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b were about half of all PIC1 wild-type alleles (wt). C, DAB stain of 6-week-old rosette leaves of Col-0 (left) and PIC1ox lines 2 and 4 (middle, segregating wild-type alleles; right, chlorotic plants, heterozygous for 35S::PIC1). D, Iron content (ng μg−1 chlorophyll g−1 fresh weight [FW]; n = 2 ± sd) in chloroplasts purified from mature leaves of Col-0 and PIC1ox line 2. In PIC1ox chloroplasts (he; red bar), the iron content was increased more than 3-fold when compared with chloroplasts of PIC1 wild-type alleles (wt; white bars). Note that the depicted iron content per chloroplast is an estimate, assuming that isolated chlorophyll per leaf fresh weight represents intact chloroplasts in each preparation. Chloroplast isolation and determination of iron levels are described in detail in “Materials and Methods.”

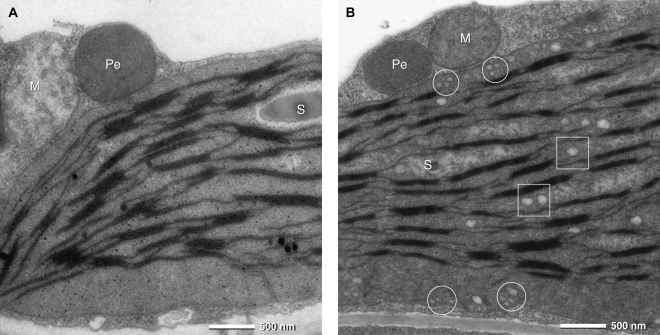

Investigation of ultrathin sections of leaves with transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 4) showed significant differences of chloroplast ultrastructure in PIC1ox lines 2 and 4 compared with the wild type: small membrane vesicles with an electron-translucent matrix (diameter about 70 nm) were accumulated throughout the stroma of PIC1ox mesophyll chloroplasts. Due to the presence of numerous, significantly smaller vesicles in the vicinity of the inner plastid envelope, they most likely originated by budding from this membrane. The structure of mitochondria and peroxisomes, however, was not altered when compared with wild-type cells.

Figure 4.

PIC1 overexpression induces vesicle formation in chloroplasts. Transmission electron micrographs of ultrathin sections from mesophyll tissue of 17-d-old rosette leaves are shown. A, Col-0. B, PIC1ox line 2. Characteristic for chloroplasts of PIC1ox lines are numerous small membrane vesicles in the vicinity of the inner envelope membrane (circles). Lager vesicles are present throughout the stroma between thylakoid membranes (squares). M, Mitochondrion; Pe, peroxisome; S, starch grain.

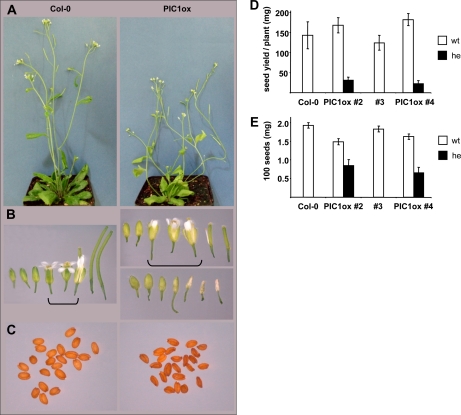

Although the developmental stage was similar to that of Col-0, PIC1ox plants produced less biomass. When measured just before bolting in 39-d-old plants, the rosette dry weight of PIC1ox line 2 was only 28% of the corresponding wild types (Supplemental Table S1). In general, adult PIC1ox plants were smaller in size and of a bushy appearance, characterized by the absence of a central inflorescence stalk (Fig. 5A). Bolting of flowers occurred simultaneously with the wild type; however, further silique and seed development was severely impaired. Either siliques did not reach their full size, producing small and shriveled seeds, or empty, crumpled siliques appeared (Fig. 5, B and C). In consequence, these defects in fruit development of PIC1ox plants led to a drastic reduction in seed yield and weight (Fig. 5, D and E) as well as to a dramatically reduced seed germination rate (between 0% and 15%). The latter was more severe in PIC1ox line 4, resulting in almost no viable seed progeny of this line. Therefore, subsequent analyses could only be performed on plants of the PIC1ox line 2.

Figure 5.

PIC1 increase causes impaired flower and seed development. A, Mature Col-0 (left) in comparison with PIC1ox line 4 (right). B, Flower and early fruit development in Col-0 (left) and PIC1ox line 2 (right). Brackets indicate developmental stages used for metal determination and microarray analysis. C, Seeds of Col-0 (left) and PIC1ox line 2 (right). D, Seed yield per plant of the Col-0 wild-type and 35S::PIC1 lines 2, 3, and 4 (n = 10 ± sd). E, Weight of 100 seeds from Col-0 and 35S::PIC1 lines 2, 3, and 4 (n = 10 ± sd). White bars in D and E depict plants with wild-type PIC1 content (wt), and black bars represent lines overexpressing PIC1 (heterozygous for 35S::PIC1; he).

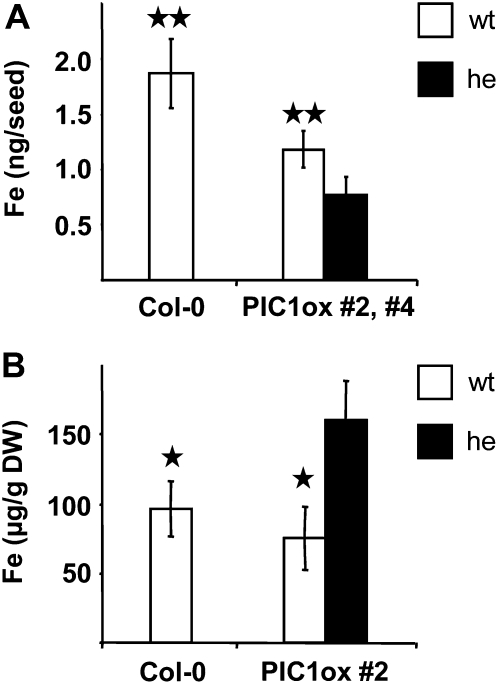

When we measured metals in dry PIC1ox seeds, we found that iron content per seed grain was significantly reduced (Fig. 6A), while the concentration of the transition metals copper, zinc, and manganese did not change (Supplemental Table S2), indicating a PIC1 impact on seed iron loading. To test whether iron deficiency or overload might influence germination of PIC1ox lines, we found that addition of neither Fe(III)-EDTA (100 μm) nor of the iron-chelator ferrozine (300 μm) increased or decreased the germination of PIC1ox lines 2 and 4 (data not shown). In contrast to seeds, impaired flower development in PIC1ox plants, however, was accompanied by an increase in iron concentration (Fig. 6B). Again, changes were iron specific, because copper, zinc, and manganese were unchanged when compared with the wild type (Supplemental Table S2).

Figure 6.

PIC1ox seeds contain low iron and flowers have elevated iron. A, Iron content (ng per seed grain; n = 5 ± sd; for Col-0, n = 3) in seeds of Col-0 and PIC1ox lines 2 and 4. B, Iron concentration (μg g−1 dry weight [DW]; n = 3 ± sd) in flowers of Col-0 and PIC1ox line 2. Asterisks indicate significantly different iron levels (two-sample Student’s t test; ** P < 0.005, * P < 0.05) in PIC1 wild-type alleles (wt; white bars) when compared with PIC1ox lines (he; black bars).

In summary, we conclude that the described phenotypic defects of PIC1ox plants most likely originated from chloroplast iron overload, which is mediated by overexpressed PIC1 proteins.

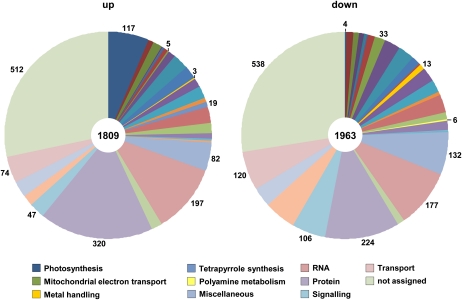

PIC1 Overexpression Leads to Deregulated Gene Expression in Flowers

Because flowers of PIC1ox plants showed impaired development in combination with elevated iron levels, we monitored differential gene expression by microarray analysis (Affymetrix ATH1 GeneChip) in the identical samples that were used for metal determination (floral stages as depicted in Fig. 5B). When we compared transcript levels in flowers of PIC1ox line 2 with those of wild-type plants, we found that 1,809 genes could be classified as up-regulated, while expression of 1,963 genes was down-regulated (Fig. 7; Supplemental Table S3). Disposition into functional categories by the MAPMAN Arabidopsis pathway analysis program revealed that besides those with still unknown functions (512 up, 538 down), the largest fractions of differentially expressed genes were assigned to the categories protein (320 up, 224 down), RNA (197 up, 177 down), miscellaneous (82 up, 132 down), transport (74 up, 120 down), and signaling (47 up, 106 down).

Figure 7.

Gene expression in PIC1ox flowers is deregulated. The distribution of differentially expressed genes into functional categories in PIC1ox versus wild-type flowers is shown. Differential expression was calculated by microarray analysis as described in “Materials and Methods.” Classification of genes was performed by MAPMAN (http://gabi.rzpd.de/projects/MapMan, version 3.1.1 [April 2, 2010]). In total, 1,809 genes were assigned to be up-regulated (left), while 1,963 genes were classified as down-regulated (right). Note that numbers and definitions of color codes apply only to regulated genes in functional categories, which are mentioned in the text (for a complete list, see Supplemental Table S3).

To further identify hotspots of regulation, we searched for functional categories that showed a high ratio between numbers of up- and down-regulated genes. The greatest differences pertained to photosynthesis, tetrapyrrole synthesis, mitochondrial electron transport, metal handling, and polyamine metabolism (Fig. 7). In particular for photosynthesis-associated genes, divergence was striking. Whereas only four genes either with a function in the Calvin cycle or photorespiration were down-regulated, transcripts of 117 genes increased. The majority of these are coding for proteins directly involved in light reactions of PSI and PSII (e.g. light-harvesting complexes or electron transport chain; for details, see Supplemental Table S3). Accordingly, genes with a function in tetrapyrrole synthesis only showed up-regulation. Thus, PIC1ox flowers are characterized by elevated iron levels and a simultaneous increase in transcripts for proteins with a function in photosynthesis as well as chlorophyll and heme biosynthesis.

Since PIC1 was previously described to function in mediating iron transport across the chloroplast inner envelope membrane (Duy et al., 2007) and metal handling was another focus for differential regulation of expression in PIC1ox flowers, we took a closer look at metal transport and homeostasis. First, we could confirm that PIC1 transcripts (11-fold induction; Table I) and proteins (Fig. 2C) were constantly and strongly increased in PIC1ox flowers. Of the eight other genes related to metal transport and up-regulated in PIC1ox flowers, five are reported to function in plastid membranes: FRO7, MAR1/IREG3, NiCo, YSL6, and PAA1/HMA6 (for details, see “Discussion”). In contrast, none of the down-regulated metal transporters, according to current knowledge, is localized in plastids. Regulation of metal handling genes (Table II) revealed the same distribution and plastid focus. On the one hand, proteins from seven of eight genes induced in PIC1ox flowers are plastid intrinsic (FSD1, CSD2, OSA1, FC2, DWARF27, ClpC1/HSP93-V, and CUTA). On the other hand, among genes of this functional category that showed transcript decrease, none is in plastids (for details, see “Discussion”).

Table I. Differentially expressed metal transport genes in PIC1ox versus the wild type.

Microarry analysis was performed on flowers of the wild type (wt) and PIC1ox line 2 (PIC1ox). Names and Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (AGI) codes for regulated metal transport genes are listed. Respective membranes (loc) of corresponding proteins are designated as follows: C-env, chloroplast envelope; C-ie, chloroplast inner envelope; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G, Golgi; PM, plasma membrane; V, tonoplast; ?, unknown. If subcellular localizations are clearly predicted but not yet experimentally verified, abbreviations are given in parentheses. The average scaled signals (n = 5 for PIC1ox, n = 6 for the wild type), the fold change (FCH), and the corresponding P values of the analysis are shown. Signals for FRO6 and FRO7 are detected by the same ATH1 probe (bracket). Annotation of genes and proteins was done according to publications and ARAMEMNON (Schwacke et al., 2003) as well as TAIR (Swarbreck et al., 2008) databases.

| Name | AGI | loc | wt | PIC1ox | FCH | P |

| Up | ||||||

| PIC1 | At2g15290 | C-ie | 956.52 | 10,421.83 | 10.90 | 1.17E-11 |

| FRO6 | At5g49730 | PM | 523.90 | 2070.95 | 3.95 | 1.37E-05 |

| FRO7 | At5g49740 | C-env | ||||

| MAR1/IREG3 | At5g26820 | C-env | 480.93 | 673.53 | 1.40 | 6.10E-04 |

| YSL6 | At3g27020 | (C-env) | 1,062.36 | 1,227.80 | 1.16 | 2.45E-02 |

| NiCo | At2g16800 | (C-env) | 492.37 | 621.87 | 1.26 | 4.43E-03 |

| PAA1/HMA6 | At4g33520 | C-ie | 264.79 | 343.00 | 1.30 | 4.09E-03 |

| COPT1 | At5g59030 | PM | 1,098.02 | 1,384.59 | 1.26 | 4.14E-03 |

| MTP1/ZAT1 | At2g46800 | V | 1,041.03 | 1,355.03 | 1.30 | 3.02E-03 |

| MTP11 | At2g39450 | ER/G | 915.42 | 1,107.12 | 1.21 | 3.12E-02 |

| Down | ||||||

| FRO8 | At5g50160 | (PM) | 315.73 | 210.84 | 0.67 | 5.06E-04 |

| IRT1 | At4g19690 | PM | 143.10 | 90.13 | 0.63 | 3.92E-02 |

| ZIP1 | At3g12750 | (PM) | 472.92 | 292.99 | 0.62 | 9.12E-04 |

| ZIP6 | At2g30080 | (PM) | 249.96 | 191.71 | 0.77 | 5.71E-03 |

| ZIFL1 | At5g13750 | (PM) | 206.87 | 134.09 | 0.65 | 1.16E-03 |

| ZTP29 | At3g20870 | ER | 932.62 | 757.43 | 0.81 | 6.30E-03 |

| PCR11 | At1g68610 | (PM) | 334.11 | 149.63 | 0.45 | 1.18E-02 |

| YSL1 | At4g24120 | (PM) | 1,185.67 | 863.06 | 0.73 | 4.08E-02 |

| YSL8 | At1g48370 | ? | 299.81 | 220.04 | 0.73 | 1.04E-02 |

| NRAMP2 | At1g47240 | ? | 341.41 | 270.11 | 0.79 | 2.59E-03 |

| NRAMP6 | At1g15960 | ? | 120.70 | 71.81 | 0.59 | 7.61E-03 |

| MGT9/MRS2-2 | At5g64560 | ? | 427.85 | 325.68 | 0.76 | 5.45E-03 |

Table II. Differential expression of genes related to metal homeostasis in PIC1ox versus the wild type.

Microarry analysis was performed on flowers of the wild type (wt) and PIC1ox line 2 (PIC1ox). Names and Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (AGI) codes of regulated genes are given. Localization (loc) of corresponding proteins is designated as follows: C, chloroplast; C-env, envelope membrane; C-ims, intermembrane space; C-str, stroma; cyt, cytosol; nuc, nucleus; ?, unknown. If subcellular destinations are clearly predicted but not yet experimentally verified, abbreviations are in parentheses. The average scaled signals (n = 5 for PIC1ox, n = 6 for the wild type), the fold change (FCH), and the corresponding P values of the analysis are listed. Annotation of genes and proteins was done according to publications and ARAMEMNON (Schwacke et al., 2003) as well as TAIR (Swarbreck et al., 2008) databases.

| Name | AGI | loc | wt | PIC1ox | FCH | P |

| Up | ||||||

| FSD1 | At4g25100 | C-str | 212.56 | 910.94 | 4.29 | 1.32E-02 |

| CSD2 | At2g28190 | C-str | 3,187.82 | 4,009.61 | 1.26 | 2.39E-03 |

| OSA1 | At5g64940 | C-env | 973.65 | 1,234.68 | 1.27 | 4.72E-03 |

| FC2 | At2g30390 | C-str | 762.15 | 881.59 | 1.16 | 3.41E-02 |

| DWARF27 family | At1g64680 | (C) | 216.31 | 361.31 | 1.67 | 1.24E-04 |

| ClpC1/HSP93-V | At5g50920 | C-str | 3,266.86 | 4,492.04 | 1.38 | 7.76E-04 |

| CUTA | At2g33740 | C-(ims) | 482.76 | 564.29 | 1.17 | 2.58E-02 |

| HMA domain | At5g03380 | ? | 329.71 | 470.26 | 1.43 | 1.15E-02 |

| Down | ||||||

| CSD1 | At1g08830 | cyt | 7,134.23 | 5,578.74 | 0.78 | 5.71E-03 |

| CCH | At3g56240 | cyt | 4,898.91 | 3,034.82 | 0.62 | 6.96E-04 |

| ATX1 | At1g66240 | cyt | 1,186.55 | 995.26 | 0.84 | 1.55E-02 |

| HMA domain | At5g17450 | ? | 498.20 | 185.93 | 0.37 | 2.29E-04 |

| HMA domain | At5g50740 | ? | 139.20 | 87.95 | 0.63 | 3.49E-02 |

| FP3 (HMA domain) | At5g63530 | ? | 646.98 | 546.59 | 0.84 | 2.21E-02 |

| FP6/HIPP26 (HMA domain) | At4g38580 | nuc | 1,166.19 | 913.89 | 0.78 | 9.05E-03 |

| MT1c | At1g07610 | ? | 1,925.47 | 1,287.33 | 0.67 | 2.44E-04 |

| MTb2 | At5g02380 | ? | 17,090.44 | 14,107.21 | 0.83 | 2.59E-03 |

| MT3 | At3g15353 | ? | 12,402.44 | 10,648.57 | 0.86 | 2.02E-02 |

| ARD1 | At4g14716 | ? | 3,163.84 | 2,481.71 | 0.78 | 9.77E-04 |

DISCUSSION

PIC1 and Ferritin Are Key Players in Balancing Iron Homeostasis as Well as Plant Growth and Development

Previously, we described PIC1 to function in iron transport across the inner envelope membrane of plastids and thus to control plastid and cellular metal homeostasis (Duy et al., 2007). In that earlier study, we found that ferritin protein clusters accumulated in plastids of pic1 knockout mutants. Because in these mutants most likely the major iron-uptake pathway into plastids was blocked, free iron accumulated in the cytosol, thereby causing severe oxidative damage. In consequence, the plant cell was up-regulating ferritin expression (Duy et al., 2007). Interestingly, Ravet et al. (2009) recently showed that in the ferritin knockout mutant fer1,3,4, which is devoid of all ferritins involved in vegetative growth, PIC1 transcript levels were increased in flowers when plants got excess iron. Thus, expression of PIC1 and ferritin is reciprocally regulated: when PIC1 proteins are lacking, ferritin levels rise, and when ferritin is missing, PIC1 is increased. This observation was underlined by the finding that in mesophyll chloroplasts from Zea mays, PIC1 belongs to the most abundant proteins identified, while ferritin was not detected. In contrast, in chloroplasts of Pisum sativum, FER1 and FER4 proteins were found, but PIC1 was absent (see Supplemental Table S3 in Bräutigam et al., 2008).

But what happens when PIC1 protein is increased in Arabidopsis chloroplasts? By generating plant lines with stable overexpression of PIC1 in this study, we could show that, again, expression of the major leaf ferritin FER1 in 2-week-old seedlings behaved contrarily to PIC1. However, even more remarkable was the high similarity of phenotypes between fer1,3,4 knockout mutants and PIC1ox lines. When fer1,3,4 plants are challenged with excess iron, they show reduced biomass, oxidative stress, as well as impaired flower development and decreased seed yield (Ravet et al., 2009). All these defects were observed in PIC1ox lines as well, although no additional iron treatment was necessary, indicating that PIC1-transport function by itself induced a rise in plastid-intrinsic iron levels (Fig. 3D). The highest correlation between fer1,3,4 and PIC1ox phenotypes was found in flowers. Here, both plant lines have elevated levels of iron, resulting in stress and in turn impaired fruit development. Due to the loss of ferritins in fer1,3,4 flower tissue, plastids are incapable of buffering excess free iron by the ferritin protein shell, which in turn is causing massive oxidative stress. Interestingly, PIC1 mRNA was increased concomitantly with floral iron accumulation (about 7-fold in Col-0 and 14-fold in fer1,3,4; Ravet et al., 2009). PIC1ox flowers in our study showed a strong increase in PIC1 transcripts, as well as proteins and had to deal with iron overload, too. Thus, as shown for leaves, an increase in PIC1 proteins in this case most likely resulted in elevated iron inside flower plastids as well, which was due to enhanced iron transport and not reduced iron storage capacity, as for ferritin knockouts. Hence, in flowers, more PIC1 protein causes the same effect as the loss of ferritin, resulting in oxidative damage followed by impaired fruit development as well as a dramatic decrease in seed yield and germination. About mechanisms of the opposite regulation of PIC1 and ferritin expression, however, we can only speculate. In the case of pic1 knockout lines, the massive induction of ferritin expression is a well-described reaction upon oxidative stress and increase of cytosolic iron levels (Duy et al., 2007; Briat et al., 2010). In PIC1ox lines, in contrast, the plant response to the regulation of ferritin expression is only slight, but as described above, mutant phenotypes and proposed roles of both proteins during plant development can be closely linked. Therefore, we conclude that in plastids, the functions of PIC1 (iron transport) and ferritin (iron storage) correlate reciprocally and that both proteins are crucial for balancing iron homeostasis throughout plant growth and development.

PIC1-Induced Oxidative Damage Is Iron Specific and Originates from Chloroplasts

Oxidative stress of PIC1ox plants most likely originated in chloroplasts, as documented by the production of H2O2, plastid intrinsic vesicle formation, decrease in chlorophyll, and iron overload in leaf chloroplasts. During the life cycle, stress became detrimental for the entire plant, resulting in leaf chlorosis and reduced biomass. In particular, iron homeostasis was impaired in flowers and seed tissue, causing severe defects during fruit development. In PIC1ox as well as pic1 knockout (Duy et al., 2007) plants, expression of the iron- and copper-dependent superoxide dismutases FSD1 and CSD2, which detoxify ROS in the chloroplast stroma (Kliebenstein et al., 1998; Abdel-Ghany et al., 2005), was differentially regulated. In particular, the pronounced up-regulation of FSD1 in PIC1ox (opposite to the down-regulation in pic1 knockouts), together with the rise of iron levels in PIC1ox flowers and leaf chloroplasts, indicate that oxidative stress is due to high iron in plastids. Although described to be cytosolic (Myouga et al., 2008), recent proteomic (Ferro et al., 2010) and GFP-targeting as well as protein import studies (W.-L. Chang and B. Bölter, unpublished data) clearly demonstrate plastid targeting of FSD1 without a classical signal peptide. The plastid origin of PIC1-controlled oxidative stress also is demonstrated by increased transcripts of the chloroplast envelope protein OSA1 in PIC1ox flowers. OSA1 (again contrarily regulated in pic1 knockouts) has been shown to play an essential role in balancing oxidative stress generated by heavy metals, H2O2, and light (Jasinski et al., 2008).

Furthermore, proteins for all other metal-handling genes with elevated expression in PIC1ox, except one, are in plastids. At the same time, three of four of these proteins are involved in iron homeostasis: ferrochelatase (FC2) assembles iron into protoporphyrin IX during heme synthesis in chloroplasts; DWARF27, a plastid-localized iron-containing protein, functions in the biosynthesis of strigolactones (Lin et al., 2009); ClpC1, originally described as HSP93-V chaperone for plastid protein import, was recently shown to be involved in iron homeostasis, since chlorosis of ClpC1 loss-of-function mutants could be rescued by iron addition (Wu et al., 2010). In contrast, down-regulation of metal homeostasis genes is neither plastid nor iron specific but rather linked to other metals. Decreased transcripts in PIC1ox flowers include those for cytosolic copper-superoxide dismutase CSD1 (plastid CSD2 is up-regulated) and copper chaperones (CCH and ATX1), which deliver copper to heavy metal P-type ATPases and are linked to senescence and oxidative stress (Himelblau et al., 1998; Mira et al., 2001; Puig et al., 2007). HMA domains (for heavy metal transport/detoxification) can be found in proteins of four other down-regulated genes that belong to a class of isoprenylated proteins binding transition metals like copper, nickel, or zinc (Dykema et al., 1999; Barth et al., 2009). The decreased transcripts MT1c, MT2b, and MT3 code for small plant metallothioneins, which function in metal homeostasis, in particular for copper, cadmium, or zinc tolerance (van Hoof et al., 2001; Zimeri et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2009; Hassinen et al., 2009). In this list, ARD1 (for acireductase dioxygenase 1), as part of the Met salvage pathway (Bürstenbinder et al., 2007), is the only down-regulated protein that requires iron. In summary, increased expression of metal-handling genes in PIC1ox flowers is clearly iron and plastid specific, indicating iron overload in chloroplasts. In contrast, down-regulated genes reflect a disturbance of cellular metal homeostasis in general.

Whereas pic1 knockout mutants were characterized by a dramatic decrease of the majority of photosynthesis proteins (Duy et al., 2007), the opposite occurred in PIC1ox plants. Here, transcript levels of most genes involved in primary photosynthesis and tetrapyrrole synthesis were higher than in the wild type. However, PIC1ox plants were suffering from chlorosis, reduced biomass, and a leaf chlorophyll decrease by 50%. Vesicle formation in plastids further indicates the accumulation of ROS, in particular H2O2, as documented by leaf staining. As in ferritin knockouts challenged with additional iron (Ravet et al., 2009), in PIC1ox flowers, the usually beneficial effects of elevated iron levels (e.g. increased biomass upon iron fertilization) became deleterious. Therefore, oxidative damage, most likely caused by iron and H2O2 accumulation in plastids, prevented efficient photosynthesis.

According to the regulation of metal homeostasis and photosynthesis genes in PIC1ox and the described phenotypical characteristics, we propose that PIC1-induced oxidative damage is iron specific and originates from plastids.

PIC1 Most Likely Functions in the Uptake and Sequestration of Iron in Plastids

The metal transport category showed a similar iron- and plastid-focused gene regulation pattern as discussed for metal homeostasis genes. In this case, five of eight genes with increased transcripts in PIC1ox flowers are reported to function in plastid membranes, while none of the down-regulated genes, according to current knowledge, is plastid localized. The most pronounced increase was for mRNA of the ferric-chelate reductases FRO6 and FRO7, which both are detected by identical probes on the ATH1 chip. Whereas FRO6 is localized in the plasma membrane, FRO7 is plastid intrinsic and might reduce ferric iron prior to uptake into chloroplasts (Jeong et al., 2008). Since across the plastid inner envelope membrane, iron most likely is transported as ferrous ion (Shingles et al., 2001, 2002), PIC1 could represent the so far unknown permease acting in concert with FRO7. Interestingly, FRO8 (down-regulated by cytosolic iron deficiency; Mukherjee et al., 2006) and nonplastid representatives of the ZIP (for ZRT/IRT-like protein) transporters are decreased in PIC1ox, again indicating plastid increase and cytosolic shortage of iron. Furthermore, down-regulation of IRT1, ZIP6, YSL1, and YSL6 (for yellow-stripe like1 and 6; see below) is also found in iron-challenged fer1,3,4 flowers (Ravet et al., 2009) that suffer from elevated free iron in plastids. Since, in addition, we could document that PIC1ox chloroplasts contained increased iron levels, we conclude that PIC1 overexpression results in plastid iron overload as well, closely linking PIC1 function to iron uptake.

Furthermore, transcripts of the chloroplast-localized MAR1/IREG3 (Conte et al., 2009) are increased in PIC1ox flowers. Because overexpression of MAR1/IREG3 causes leaf chlorosis that can be rescued by iron, it was suggested that this aminoglycoside transporter might function naturally in uptake of the iron-chelating polyamine NA (Conte and Lloyd, 2010). Interestingly, leaf chlorosis induced by MAR1/IREG3 and PIC1 overexpression showed similar progression along the midveins, while chlorosis of NA synthase-less mutants is described to be interveinal (Ling et al., 1999; Klatte et al., 2009). Conte and coworkers (Conte et al., 2009; Conte and Lloyd, 2010) argue that the unusual MAR1/IREG3-mediated midvein chlorosis might be due to redistribution of the cytoplasmic NA pool to plastids. In consequence, iron would be sequestered within the organelles, and NA function in long-distance transport of metals, which for iron most likely is in phloem loading/unloading processes (for review, see Curie et al., 2009), would be restricted. Therefore, it seems likely that PIC1-mediated veinal chlorosis might be due to increased and immobilized plastid iron and in turn disturbed iron and NA homeostasis in the phloem.

Another link to iron-NA transport in PIC1ox flowers is provided by specific down-regulation of polyamine biosynthesis genes connected to NA synthesis and up-regulation of the potential iron-NA transporter YSL6 (for overview, see Curie et al., 2009). Only recently, YSL6 was reported to be integral to chloroplast envelope membranes as well; however, the direction and substrates of transport have not yet been clarified (C. Curie, personal communication). In contrast to YSL6, transcripts of YSL1 and YSL8 are decreased in PIC1ox flowers. YSL1, most likely in the plasma membrane, fulfills a function in the delivery of iron-NA chelates to seeds, as demonstrated by the decreased levels of iron and NA in ysl1 knockout seeds (Le Jean et al., 2005). Because PIC1ox seeds too suffered from iron shortage, it is tempting to speculate that increased PIC1 function accumulates iron inside plastids, thereby disturbing NA distribution as well and subsequently influencing fruit development and in particular seed iron loading.

In conclusion, the majority of effects caused by PIC1 overexpression, in particular the significant accumulation in PIC1ox chloroplasts, together with the fact that PIC1 mediated iron uptake into yeast cells and the strong iron-deficient phenotype of pic1 knockouts (Duy et al., 2007) favor a function of PIC1 in iron influx into plastids.

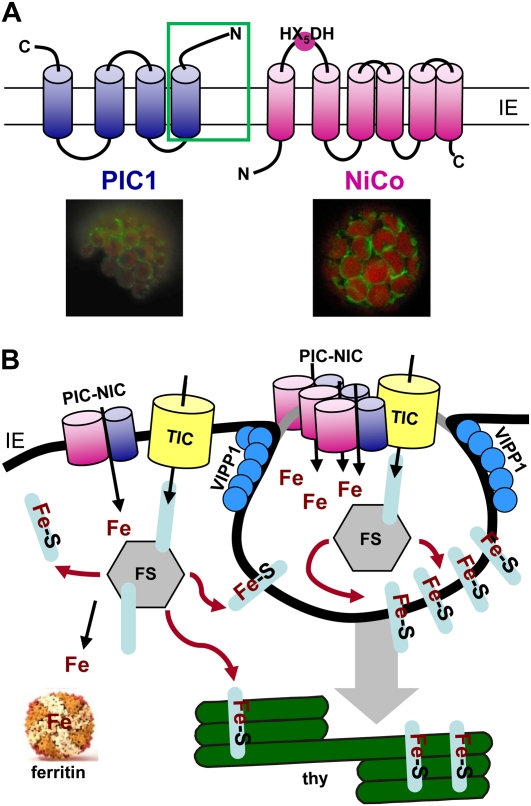

The Function of PIC1

The protein NiCo, whose corresponding transcripts are increased in PIC1ox flowers, is targeted to chloroplast envelopes and predicted to function in the transport of nickel and/or cobalt (Fig. 8A; The Arabidopsis Information Resource [TAIR] gene model at www.arabidopsis.org [June 15, 2009]). Only recently, we identified NiCo in a yeast-based screen for PIC1-interacting proteins (R. Stübe and K. Philippar, unpublished data). Furthermore, the orthologous protein in Nicotiana benthamiana is annotated as “chloroplast zebra-necrosis protein” (GenBank accession no. ACA03877), suggesting chlorotic NiCo mutant phenotypes similar to PIC1ox or knockout plants. With a general low specificity of plant transporters for divalent metal ions (compare for IRT1; Korshunova et al., 1999), it thus is tempting to speculate that PIC1 and NiCo might function together in plastid iron transport, although interaction so far was shown in heterozygous yeast only. Presumably, PIC1 in this potential chloroplast metal translocon (Fig. 8B) is not directly transporting iron but rather regulating or modulating a NiCo-like transporter.

Figure 8.

Model of a potential metal translocon in the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts. A, PIC1 and NiCo insert into the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts (IE), most likely with four and six α-helical domains, respectively. The potential metal-binding amino acid motif HX5DH defines NiCo as a member of the Ni2+-Co2+ transporter family (Transporter Classification Database; www.tcdb.org). The first helix and the soluble N terminus of PIC1 (green box) are predicted to contain a TonB-dependent receptor protein signature (Prosite prediction; www.expasy.ch). In a yeast split ubiquitin assay, this domain was necessary and sufficient to mediate the interaction with NiCo (R. Stübe and K. Philippar unpublished data). The bottom panels show in vivo targeting of PIC1-GFP and NiCo-GFP fusion proteins performed as described by Duy et al. (2007). Green represents GFP signals and red represents chlorophyll autofluorescence. B, The hypothetical metal translocon, consisting of PIC1 and NiCo subunits (PIC-NIC), is shuttling iron (Fe) across the inner envelope of chloroplasts (IE; black line). In proximity, the TIC protein translocon imports proteins (for details, see Jouhet and Gray, 2009). The FeS protein biogenesis machinery (FS) in the stroma generates FeS cluster proteins, which are subsequently targeted to their destination (e.g. inserted into thylakoid membranes [thy]). Excess iron can be buffered by ferritin. At right, overproduction of PIC1 might cause VIPP1-mediated formation of vesicles, which contain elevated iron levels and are destined to fuse with thylakoid membranes.

Because vesicles in PIC1ox seem to bud from the inner plastid membrane, a function of PIC1 in iron handover to either ferritin proteins and/or the FeS cluster biogenesis machinery (for overview, see Ye et al., 2006; Rouhier et al., 2010) might be possible as well (Fig. 8B). In consequence, PIC1-induced vesicles in plastids would be overloaded with accumulating proteins for photosynthetic light harvesting and electron transport, in particular FeS cluster or heme proteins, which subsequently could not be integrated into functional complexes in thylakoids. This hypothesis is supported by the up-regulation of genes for plastid FeS cluster biogenesis (CpSufE, HCF101), heme synthesis (ferrochelatase), and FeS cluster proteins (GLU1, CAO, TIC55) in PIC1ox (for details, see Supplemental Table S3). Thus, the hypothetical model depicted in Figure 8B could explain VIPP1-like (for vesicle-inducing protein in plastids 1) vesicle budding in PIC1ox plastids (Kroll et al., 2001) as well as potential beneficiary effects on protein import. (1) VIPP1 (also up-regulated in PIC1ox) is functioning in thylakoid membrane biogenesis/maintenance by inducing vesicle formation from the inner plastid membrane and thereby most likely channeling imported preproteins to their thylakoid destination (for review, see Vothknecht and Soll, 2005; Jouhet and Gray, 2009). (2) In parallel to its function in iron transport, PIC1 was described as TIC21, being part of the preprotein translocon in the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts (Teng et al., 2006; Kikuchi et al., 2009). Thus, PIC1 in loose association with the actual protein translocon channels TIC20 and/or TIC110 could deliver iron to the FeS cluster biogenesis machinery and thereby drive the assembly of FeS clusters into freshly imported proteins as well as subsequent VIPP1-mediated vesicle budding.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our data strongly suggest a function of PIC1 in mediating iron transport across the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts. Whether this role is in direct transport or more oblique in regulating other transporters or the handover of iron still remains to be clarified. Although we cannot fully exclude an export function of PIC1, according to the PIC1-mediated iron accumulation in chloroplasts (this study) and in complemented yeast cells (Duy et al., 2007) as well as due to the described phenotypes of pic1 knockout (iron-deficiency symptoms) and PIC1ox plants (iron-overload appearance), iron uptake is most likely. Together with ferritin, therefore, PIC1 represents a crucial element for the integration of plastid iron homeostasis into plant growth and development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth

All experiments were performed on Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Col-0 (Lehle Seeds) and the respective 35S::PIC1 lines. Before sowing, seeds were surface sterilized and kept at 4°C for 3 d. If not indicated otherwise, seedlings were grown for 2 weeks on plates (0.3% Gelrite medium [Roth], 1% d-Suc, and 0.5× Murashige and Skoog salts, pH 5.7) and afterward transferred to soil. Plant growth occurred in chambers with a 16-h-light (21°C; photon flux density of 100 μmol m−2 s−1)/8-h-dark (16°C) cycle.

To generate plants overexpressing PIC1 under the control of the 35S promoter, the 888-bp-long coding sequence of PIC1 (Duy et al., 2007) was subcloned into the plasmid vector pH2GW7 (Karimi et al., 2002). PIC1/pH2GW7 was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 cells, which subsequently were used to transfect Col-0 plants as described by Duy et al. (2007). T1 lines were selected by hygromycin (30 μg mL−1), and stable insertion of 35S::PIC1 was verified by PCR genotyping (T1 and T2 generations).

Immunoblot Analysis

Total leaf and flower proteins were extracted for 30 min on ice in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm EDTA, 2% lithium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mm dithiothreitol, and 100 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cell debris was pelleted for 15 min at 14,000g and 4°C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P polyvinyl difluoride membrane (Millipore). Polyclonal antiserum against recombinant PIC1 protein (Duy et al., 2007) was raised in rabbit (Pineda Antibody Service) and used in a 1:1,000 dilution (0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 m NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were diluted 1:8,000. Nonspecific signals were blocked by 1% skim milk powder and 0.03% bovine serum albumin. Blots were stained with 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 0.5% (w/v) luminol, 0.22% (w/v) coumaric acid, and 0.009% (v/v) H2O2. Luminescence was detected by Kodak Biomax MR films (Perkin-Elmer). FSD1 immunostaining was performed as described by Duy et al. (2007).

Chlorophyll Extraction

For chlorophyll extraction, a defined leaf area of 0.64 cm2 was punched and quickly ground in 1 mL of 80% acetone. After 10 min of dark incubation, cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000g for 10 min. Chlorophyll a and b contents in the supernatant were measured in a spectrophotometer (750, 663, and 645 nm) and calculated as described (Arnon, 1949).

Detection of H2O2

H2O2 was visually detected by using 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) according to Thordal-Christensen et al. (1997). Leaves were vacuum infiltrated with 1 mg mL−1 DAB (pH 3.8) for 20 min, followed by DAB incubation for 8 h at 25°C and subsequent washing in distilled, deionized water. The reaction was stopped by 10 min of immersion in boiling ethanol. Residual chlorophyll was extracted with fresh ethanol.

Electron Microscopy

For electron microscopy, plantlets were grown for 17 d on plates. Fixation and embedding of leaf tissue as well as preparation of ultrathin sections were performed as described (Duy et al., 2007). Micrographs were taken with an EM 912 electron microscope (Zeiss) equipped with an integrated Ω energy filter operated in the zero loss mode.

Chloroplast Isolation and Determination of Metal Content

To provide independent biological replicates, chloroplasts were isolated twice from mature leaf tissue of PIC1ox line 2 and the Col-0 wild type as described by Philippar et al. (2007). Subsequently, iron concentration (see below) was measured in 100 μL of lyophilized chloroplast suspension. To estimate the iron content per chloroplast, we determined the yield of chlorophyll per fresh weight of leaf tissue initially used for chloroplast preparation. This value was used as a measure for intact chloroplasts and to normalize iron levels in all preparations (for data, see Supplemental Table S1). The observation that we could isolate significantly less intact chloroplasts per g fresh weight from PIC1ox leaves was underlined by the fact that equal leaf areas contained decreased chlorophyll as well (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Table S1). Note that the calculated iron content per chloroplast is an estimate, assuming that chlorophyll per fresh weight represents intact chloroplasts.

For concentration measurements of copper, iron, manganese, and zinc, 100 mg of fresh flower tissue and 20 mg of seeds were sampled from at least 10 individual plants. Metals in all tissue samples were determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry analysis after pressure digestion (Central Inorganic Analysis Service, Helmholtz Zentrum München).

Transcript Level Profiling

Total RNA was isolated using the Plant RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed as described by Duy et al. (2007). To decrease biological variation, three samples each of 10 seedlings were harvested and at least two technical replicates were accomplished.

For microarray analysis, flowers (Fig. 5B) of mature heterozygous PIC1ox line 2 and wild-type plants were used. To provide biological replicates, five PIC1ox and six wild-type samples were harvested from 10 individual plants. RNA (5 μg) was processed and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip Arabidopsis ATH1 Genome Arrays using the Affymetrix One-Cycle Labeling and Control (Target) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Affymetrix). Raw signal intensity values (CEL files) from PIC1ox (n = 5) and the wild type (n = 6) were computed from the scanned array images using the Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console 3.0. For quality check and normalization, the raw intensity values were processed with Robin software (Lohse et al., 2010) default settings. Specifically, for background correction, the robust multiarray average normalization method (Irizarry et al., 2003) was performed across all arrays (between-array method). Statistical analysis of differential gene expression of PIC1ox versus wild-type flowers was carried out using the linear model-based approach developed by Smyth (2004). The obtained P values were corrected for multiple testing using the nestedF procedure, applying a significance threshold of 0.05 in combination with the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) false-discovery rate control. Genes that showed a signal difference between PIC1ox and the wild type greater than 30 (arbitrary units) were considered to be differentially expressed.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Parameters determined during phenotype analysis of PIC1ox plants.

Supplemental Table S2. Metal concentration in flowers and seeds of PIC1ox and the wild type.

Supplemental Table S3. Differentially expressed genes in PIC1ox versus wild-type flowers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julia Neumann and Silvia Dobler for technical assistance and Ann-Christine König for intensive work on PIC1ox seeds (all from Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany). Antiserum against FSD1 was donated by Marinus Pilon (Colorado State University, Fort Collins).

References

- Abdel-Ghany SE, Müller-Moulé P, Niyogi KK, Pilon M, Shikanai T. (2005) Two P-type ATPases are required for copper delivery in Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplasts. Plant Cell 17: 1233–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon DI. (1949) Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol 24: 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (1999) The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygen and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 601–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth O, Vogt S, Uhlemann R, Zschiesche W, Humbeck K. (2009) Stress induced and nuclear localized HIPP26 from Arabidopsis thaliana interacts via its heavy metal associated domain with the drought stress related zinc finger transcription factor ATHB29. Plant Mol Biol 69: 213–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57: 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam A, Hoffmann-Benning S, Weber APM. (2008) Comparative proteomics of chloroplast envelopes from C3 and C4 plants reveals specific adaptations of the plastid envelope to C4 photosynthesis and candidate proteins required for maintaining C4 metabolite fluxes. Plant Physiol 148: 568–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briat JF, Ravet K, Arnaud N, Duc C, Boucherez J, Touraine B, Cellier F, Gaymard F. (2010) New insights into ferritin synthesis and function highlight a link between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in plants. Ann Bot (Lond) 105: 811–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bughio N, Takahashi M, Yoshimura E, Nishizawa NK, Mori S. (1997) Light-dependent iron transport into isolated barley chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol 38: 101–105 [Google Scholar]

- Bürstenbinder K, Rzewuski G, Wirtz M, Hell R, Sauter M. (2007) The role of methionine recycling for ethylene synthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J 49: 238–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro A, Puntarulo S. (1996) Effect of in vivo iron supplementation on oxygen radical production by soybean roots. Biochim Biophys Acta 1291: 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte S, Stevenson D, Furner I, Lloyd A. (2009) Multiple antibiotic resistance in Arabidopsis is conferred by mutations in a chloroplast-localized transport protein. Plant Physiol 151: 559–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte SS, Lloyd AM. (2010) The MAR1 transporter is an opportunistic entry point for antibiotics. Plant Signal Behav 5: 49–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C, Cassin G, Couch D, Divol F, Higuchi K, Le Jean M, Misson J, Schikora A, Czernic P, Mari S. (2009) Metal movement within the plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Ann Bot (Lond) 103: 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duy D, Wanner G, Meda AR, von Wirén N, Soll J, Philippar K. (2007) PIC1, an ancient permease in Arabidopsis chloroplasts, mediates iron transport. Plant Cell 19: 986–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykema PE, Sipes PR, Marie A, Biermann BJ, Crowell DN, Randall SK. (1999) A new class of proteins capable of binding transition metals. Plant Mol Biol 41: 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro M, Brugière S, Salvi D, Seigneurin-Berny D, Court M, Moyet L, Ramus C, Miras S, Mellal M, Le Gall S, et al. (2010) AT_CHLORO, a comprehensive chloroplast proteome database with subplastidial localization and curated information on envelope proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 1063–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W, Xiao S, Li H-Y, Tsao S-W, Chye M-L. (2009) Arabidopsis thaliana acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP2 interacts with heavy-metal-binding farnesylated protein AtFP6. New Phytol 181: 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Meetam M, Goldsbrough PB. (2008) Examining the specific contributions of individual Arabidopsis metallothioneins to copper distribution and metal tolerance. Plant Physiol 146: 1697–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. (1992) Biologically relevant metal ion-dependent hydroxyl radical generation: an update. FEBS Lett 307: 108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen VH, Tuomainen M, Peräniemi S, Schat H, Kärenlampi SO, Tervahauta AI. (2009) Metallothioneins 2 and 3 contribute to the metal-adapted phenotype but are not directly linked to Zn accumulation in the metal hyperaccumulator, Thlaspi caerulescens. J Exp Bot 60: 187–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelblau E, Mira H, Lin SJ, Culotta VC, Peñarrubia L, Amasino RM. (1998) Identification of a functional homolog of the yeast copper homeostasis gene ATX1 from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 117: 1227–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski M, Sudre D, Schansker G, Schellenberg M, Constant S, Martinoia E, Bovet L. (2008) AtOSA1, a member of the Abc1-like family, as a new factor in cadmium and oxidative stress response. Plant Physiol 147: 719–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Cohu C, Kerkeb L, Pilon M, Connolly EL, Guerinot ML. (2008) Chloroplast Fe(III) chelate reductase activity is essential for seedling viability under iron limiting conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10619–10624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouhet J, Gray JC. (2009) Is chloroplast import of photosynthesis proteins facilitated by an actin-TOC-TIC-VIPP1 complex?. Plant Signal Behav 4: 986–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfenkel K, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. (1995) Effects of iron excess on Nicotiana plumbaginifolia plants. Plant Physiol 107: 725–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Inzé D, Depicker A. (2002) Gateway vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci 7: 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Oishi M, Hirabayashi Y, Lee DW, Hwang I, Nakai M. (2009) A 1-megadalton translocation complex containing Tic20 and Tic21 mediates chloroplast protein import at the inner envelope membrane. Plant Cell 21: 1781–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatte M, Schuler M, Wirtz M, Fink-Straube C, Hell R, Bauer P. (2009) The analysis of Arabidopsis nicotianamine synthase mutants reveals functions for nicotianamine in seed iron loading and iron deficiency responses. Plant Physiol 150: 257–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliebenstein DJ, Monde RA, Last RL. (1998) Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis: an eclectic enzyme family with disparate regulation and protein localization. Plant Physiol 118: 637–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korshunova YO, Eide D, Clark WG, Guerinot ML, Pakrasi HB. (1999) The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol Biol 40: 37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosman DJ. (2010) Redox cycling in iron uptake, efflux, and trafficking. J Biol Chem 285: 26729–26735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll D, Meierhoff K, Bechtold N, Kinoshita M, Westphal S, Vothknecht UC, Soll J, Westhoff P. (2001) VIPP1, a nuclear gene of Arabidopsis thaliana essential for thylakoid membrane formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4238–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jean M, Schikora A, Mari S, Briat JF, Curie C. (2005) A loss-of-function mutation in AtYSL1 reveals its role in iron and nicotianamine seed loading. Plant J 44: 769–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Wang R, Qian Q, Yan M, Meng X, Fu Z, Yan C, Jiang B, Su Z, Li J, et al. (2009) DWARF27, an iron-containing protein required for the biosynthesis of strigolactones, regulates rice tiller bud outgrowth. Plant Cell 21: 1512–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling HQ, Koch G, Bäumlein H, Ganal MW. (1999) Map-based cloning of chloronerva, a gene involved in iron uptake of higher plants encoding nicotianamine synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7098–7103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M, Nunes-Nesi A, Krüger P, Nagel A, Hannemann J, Giorgi FM, Childs L, Osorio S, Walther D, Selbig J, et al. (2010) Robin: an intuitive wizard application for R-based expression microarray quality assessment and analysis. Plant Physiol 153: 642–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira H, Martínez-García F, Peñarrubia L. (2001) Evidence for the plant-specific intercellular transport of the Arabidopsis copper chaperone CCH. Plant J 25: 521–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira D, Le Guyader H, Philippe H. (2000) The origin of red algae and the evolution of chloroplasts. Nature 405: 69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel FMM, Price NM. (2003) The biogeochemical cycles of trace metals in the oceans. Science 300: 944–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey J, Baxter IR, Lee J, Li L, Lahner B, Grotz N, Kaplan J, Salt DE, Guerinot ML. (2009) The ferroportin metal efflux proteins function in iron and cobalt homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 3326–3338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubarakshina MM, Ivanov BN, Naydov IA, Hillier W, Badger MR, Krieger-Liszkay A. (2010) Production and diffusion of chloroplastic H2O2 and its implication to signalling. J Exp Bot 61: 3577–3587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee I, Campbell NH, Ash JS, Connolly EL. (2006) Expression profiling of the Arabidopsis ferric chelate reductase (FRO) gene family reveals differential regulation by iron and copper. Planta 223: 1178–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myouga F, Hosoda C, Umezawa T, Iizumi H, Kuromori T, Motohashi R, Shono Y, Nagata N, Ikeuchi M, Shinozaki K. (2008) A heterocomplex of iron superoxide dismutases defends chloroplast nucleoids against oxidative stress and is essential for chloroplast development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 3148–3162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CM, Guerinot ML. (2009) Facing the challenges of Cu, Fe and Zn homeostasis in plants. Nat Chem Biol 5: 333–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JD. (2000) A single birth of all plastids?. Nature 405: 32–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekker I, Tel-Or E, Mittler R. (2002) Reactive oxygen intermediates and glutathione regulate the expression of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase during iron-mediated oxidative stress in bean. Plant Mol Biol 49: 429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippar K, Geis T, Ilkavets I, Oster U, Schwenkert S, Meurer J, Soll J. (2007) Chloroplast biogenesis: the use of mutants to study the etioplast-chloroplast transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 678–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Mira H, Dorcey E, Sancenón V, Andrés-Colás N, Garcia-Molina A, Burkhead JL, Gogolin KA, Abdel-Ghany SE, Thiele DJ, et al. (2007) Higher plants possess two different types of ATX1-like copper chaperones. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354: 385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA, Evans MCE, Korb RE. (1999) The role of trace metals in photosynthetic electron transport in O2 evolving organisms. Photosynth Res 60: 111–149 [Google Scholar]

- Ravet K, Touraine B, Boucherez J, Briat JF, Gaymard F, Cellier F. (2009) Ferritins control interaction between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J 57: 400–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Procter CM, Connolly EL, Guerinot ML. (1999) A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature 397: 694–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhier N, Couturier J, Johnson MK, Jacquot JP. (2010) Glutaredoxins: roles in iron homeostasis. Trends Biochem Sci 35: 43–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf G, Honsbein A, Meda AR, Kirchner S, Wipf D, von Wirén N. (2006) AtIREG2 encodes a tonoplast transport protein involved in iron-dependent nickel detoxification in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. J Biol Chem 281: 25532–25540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R, Schneider A, van der Graaff E, Fischer K, Catoni E, Desimone M, Frommer WB, Flügge UI, Kunze R. (2003) ARAMEMNON, a novel database for Arabidopsis integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol 131: 16–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingles R, North M, McCarty RE. (2001) Direct measurement of ferrous ion transport across membranes using a sensitive fluorometric assay. Anal Biochem 296: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingles R, North M, McCarty RE. (2002) Ferrous ion transport across chloroplast inner envelope membranes. Plant Physiol 128: 1022–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. (2004) Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3: Article 3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbreck D, Wilks C, Lamesch P, Berardini TZ, Garcia-Hernandez M, Foerster H, Li D, Meyer T, Muller R, Ploetz L, et al. (2008) The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D1009–D1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YS, Su YS, Chen LJ, Lee YJ, Hwang I, Li HM. (2006) Tic21 is an essential translocon component for protein translocation across the chloroplast inner envelope membrane. Plant Cell 18: 2247–2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry N, Low G. (1982) Leaf chlorophyll content and its relation to the intracellular location of iron. J Plant Nutr 5: 301–310 [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H, Zhang Z, Wei Y, Collinge DB. (1997) Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants, H2O2 accumulation in papillae, and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J 11: 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof NA, Hassinen VH, Hakvoort HW, Ballintijn KF, Schat H, Verkleij JA, Ernst WH, Kärenlampi SO, Tervahauta AI. (2001) Enhanced copper tolerance in Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke populations from copper mines is associated with increased transcript levels of a 2b-type metallothionein gene. Plant Physiol 126: 1519–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vert G, Grotz N, Dédaldéchamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat JF, Curie C. (2002) IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14: 1223–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vothknecht UC, Soll J. (2005) The protein import pathway into chloroplasts: a single tune or variations on a common theme? In SG Möller, , Plastids: Annual Plant Reviews, Vol 13 Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, pp; 157–179 [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ji Y, Du J, Kong D, Liang H, Ling HQ. (2010) ClpC1, an ATP-dependent Clp protease in plastids, is involved in iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis leaves. Ann Bot (Lond) 105: 823–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H, Pilon M, Pilon-Smits EAH. (2006) CpNifS-dependent iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis in chloroplasts. New Phytol 171: 285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimeri AM, Dhankher OP, McCaig B, Meagher RB. (2005) The plant MT1 metallothioneins are stabilized by binding cadmiums and are required for cadmium tolerance and accumulation. Plant Mol Biol 58: 839–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]