Abstract

Soluble guanylate cyclase is an NO-sensing hemoprotein that serves as a NO receptor in NO-mediated signaling pathways. It has been believed that this enzyme displays no measurable affinity for O2, thereby enabling the selective NO sensing in aerobic environments. Despite the physiological significance, the reactivity of the enzyme-heme for O2 has not been examined in detail. In this paper we demonstrated that the high spin heme of the ferrous enzyme converted to a low spin oxyheme (Fe2+-O2) when frozen at 77 K in the presence of O2. The ligation of O2 was confirmed by EPR analyses using cobalt-substituted enzyme. The oxy form was produced also under solution conditions at −7 °C, with the extremely low affinity for O2. The low O2 affinity was not caused by a distal steric protein effect and by rupture of the Fe2+-proximal His bond as revealed by extended x-ray absorption fine structure. The midpoint potential of the enzyme-heme was +187 mV, which is the most positive among high spin protoheme-hemoproteins. This observation implies that the electron density of the ferrous heme iron is relatively low by comparison to those of other hemoproteins, presumably due to the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond. Based on our results, we propose that the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond is a key determinant for the low O2 affinity of the heme moiety of soluble guanylate cyclase.

Keywords: Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR), Guanylate Cyclase (Guanylyl Cyclase), Heme, Nitric Oxide, Oxygen Binding, X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy, EXAFS, Hemoprotein, Oxidation-Reduction Potential

Introduction

Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC)2 is a well characterized NO receptor involved in cell-cell signal transduction pathways associated with neuronal communication and vasodilation (1–7). Mammalian sGC is a heterodimeric (αβ) hemoprotein (8–10) in which the β subunit binds a stoichiometric amount of heme via a weak bond between the heme iron and His-104 (11–14). The binding of NO to the ferrous heme cleaves the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond, and the resultant NO complex with 5-coordinate NO heme markedly stimulates the enzymic production of cGMP (9, 14–17). The enzyme-heme also binds carbon monoxide (CO) with moderate stimulation of enzyme activity. It has been thought that the ferrous enzyme-heme in sGC does not exhibit a measurable affinity for O2 despite having a vacant axial position on the heme (9). This is in contrast to other hemoproteins with a Fe2+-proximal His linkage, including globins and heme-containing oxygenases. The lack of affinity for O2 allows sGC to function as a selective NO-sensor even in the presence of high concentrations of O2 and prevents oxidation of ferrous heme by O2.

We have examined the reaction of the enzyme-heme in sGC with external ligands using a rapid scan-stopped flow method as well as EPR, resonance Raman, and an infrared spectroscopy and established the following. (i) A 5-coordinate NO complex is produced via 6-coordinate NO complex in the reaction with NO (14). (ii) The ferric heme of sGC combines N3− to form a unique 5-coordinate high spin complex with a high cyclase activity (14). (iii) YC-1(3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-3′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole), an allosteric activator, induces the coordination changes in the CO complex from 6-coordinate CO heme to a 5-coordinate CO heme (17). Most of these anomalous heme coordination structures are specific to soluble guanylate cyclase among hemoproteins and seem to be associated with the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond.

X-ray Structural analyses of the H-NOX (heme-NO/oxygen binding) or SONO (sensor of nitric oxide) domain, which share considerable sequence homology with the sGC heme domain, have been carried out to identify possible key determinants for modulating the O2 binding ability of sGC (18, 19). H-NOX/SONO have a proximal His residue that is probably involved in the signaling pathway for O2 and/or NO. Spectroscopic characterization revealed that the H-NOX/SONO heme sensor domain from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, an obligate anaerobe, produced a 6-coordinate NO heme and a stable oxy-heme (Fe2+-O2), reminiscent of globins (19, 20). By contrast, the H-NOX/SONO protein from Clostridium botulinum resembles mammalian and insect sGCs (21) and forms a stable 5-coordinate NO heme but not a stable oxy heme (18). The crystal structure of the oxy form of T. tengcongensis H-NOX revealed that a Tyr residue on the distal side of the heme was involved in hydrogen bond formation with the bound O2 molecule (19). However, H-NOX proteins from facultative aerobes as well as typical NO-regulated sGCs from mammalian sources possess an Ile residue at the position corresponding to the distal Tyr (19). Replacement of the Tyr residue with Ile markedly reduced the O2 affinity of the heme-domain of the T. tengcongensis protein, thereby substantiating the crucial role of the distal Tyr in the discrimination of O2 binding in the H-NOX proteins (20).

Mammalian sGC contains Ile-145 at the position homologous to the distal Tyr. Boon et al. (20) converted the Ile-145 of sGC β-subunit homodimer to Tyr and found that the mutant homodimer produced a stable oxy form, although the affinity for O2 was extremely low. Hence, it was hypothesized that the absence of a hydrogen-bonding residue in the distal heme pocket is essential for O2 exclusion by sGC. Martin et al. (22) have tested the hypothesis by employing a complete human sGC heterodimer. However, substitution of Ile-145 with Tyr in the β-subunit did not facilitate the binding of O2 to the enzyme. This unexpected finding may be due to the inappropriate orientation of the Tyr phenolic OH group relative to the ligand. Indeed, a recent publication revealed that an additional mutation, I149E, in the distal pocket enabled the enzyme-heme to react with O2 (23). The I149E mutation probably induces a repositioning of the phenolic OH group of the introduced Tyr toward the bound O2, facilitating the formation of a hydrogen bond. Although the above mutational study demonstrates that a hydrogen bond in the distal pocket is one of the main factors responsible for the stabilization of bound O2, the oxy form of the mutant enzyme was still unstable and only detected as a transient species. This finding implies that an additional factor(s) might be involved in the mechanism to control the reactivity of the heme for O2. Despite the important implication, detailed experiments to examine the reaction of sGC with O2 have not been reported. In the present paper we describe the detection and characterization of the oxy form of sGC.

When ferrous sGC was frozen at 77 K, we found that the enzyme-heme converted to a new species with an optical spectrum similar to that of oxyhemoglobin. The new species was also produced under fluid conditions at −7 °C, but the amount was remarkably small, suggesting an extremely low O2 affinity of the ferrous heme. This species was assigned to be an oxy form by the spectral similarity with oxymyoglobin, by the inhibitory action of isocyanide for the new species formation, and by EPR characterization of the corresponding form of the Co2+-porphyrin-substituted enzyme. EXAFS analyses revealed that upon binding O2, the ferrous iron in the out-of-plane position moved toward the heme plane without rupture of the Fe2+-proximal His bond. These results indicate that the oxy form is in a 6-coordinate state and that the low affinity for O2 is not caused by cleavage of the Fe2+-proximal His bond. Electrochemical analyses revealed that the enzyme-heme had the most positive midpoint potential (+187 mV) among high spin protoheme-containing hemoproteins. This result strongly suggests that the electron density on the ferrous heme in sGC is significantly lowered relative to the ferrous heme of other hemoproteins. The decrease in the electron density, which may be due to the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond, weakens the Fe2+-O2 bond strength as a result of diminished electron donation from iron to O2. Our results suggest the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond is a critical factor that could account for the lower O2 affinity of sGC. By contrast, the distal protein effect, comprising steric hindrance in the distal heme pocket, had no significant impact on the ligand binding of sGC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Enzyme Purification

Fresh bovine lung (5 kg) was minced and homogenized using a Waring blender in 15-liters of 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm benzamidine, and 1 mm EDTA) and 55 mm β-mercaptoethanol (14, 17, 24). Protease inhibitors and β-mercaptoethanol were included in all the buffers throughout the purification unless stated otherwise. The successive purification steps of the enzyme were the same as those described earlier (24). The purified enzyme preparations were stored in liquid nitrogen until use.

Spectral Measurements

The formation of the oxy form was examined under the solution conditions at 3 and −7 °C. The experiments at subzero temperature were carried out in 40 mm TEA buffer, pH 7.5, containing 10% (v/v) ethylene glycol as antifreeze. The temperature of the cuvette holder was maintained at −7 °C or 3 °C by thermomodule elements. The fully reduced sGC was added to the anaerobic buffer solution in a septum-sealed anaerobic cuvette that was kept in an anaerobic state by flushing with N2 gas. The optical absorption spectra under the conditions were recorded on a PerkinElmer Life Sciences Lambda 18 spectrophotometer, and 5∼6 scans were averaged to improve the signal to noise ratio. After the spectra of the ferrous enzyme were collected, the solution was kept in two atmospheres of O2 gas introduced via the septum. Optical spectra were recorded (average of 5∼6 scans) after carefully shaking to equilibrate with O2.

Optical spectra at 77 K were measured on a Shimadzu MPS-2450 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a homemade low temperature attachment consisting of a liquid N2 Dewar and twin cuvettes (light path, 1 mm) for sample and reference solutions, as reported previously (25). To obtain a well balanced spectrum at 77 K, the buffer containing 5% ethylene glycol was employed.

EPR spectra were measured on a Varian E-12 X-band EPR spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) with a 100-kHz field modulation. The sample temperature was controlled with an Oxford ESR-900 cryostat as described previously (14, 17).

The iron K-edge EXAFS measurements were performed using synchrotron radiation at station BLC12C of Photon Factory in the National Laboratory of High Energy Physics (Tsukuba, Japan). EXAFS data were collected at 80 K as fluorescence spectra using a 13-element germanium array detector. The results presented in this paper are the average of multiple scans. Data analyses were carried out as described previously (26–28). EXAFS, which were extracted by subtracting the background absorption, was converted to electron momentum k space, where k is a photoelectron wave vector. The resultant curve was then multiplied by k3 to equalize the oscillation amplitude in the k space. Curve fittings were performed using the non-linear least squares program EXCURV92 on the raw data weighted by k3. Other details, including refinement of the data, are described elsewhere (26–28).

Resonance Raman spectra were measured with a JASCO NR-1800 spectrophotometer equipped with a cooled charge-coupled device detector (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ). The excitation wavelength was 413.1 nm from a krypton ion laser (Coherent, Innova 90). The sample was directly mounted on an aluminum sample holder and frozen with liquid N2. The sample holder was then inserted into the cryostat (Oxford DN1704), and the temperature of the sample was kept at 85 K with a temperature controller (Oxford ITC502).

Stopped-flow Measurements

The binding of alkyl isocyanides to the ferrous sGC was followed by a DX-18MV stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK). The anaerobic sGC solution was mixed with an anaerobic solution containing a desired amount of t-butyl or isopropyl isocyanide in the stopped-flow instrument at 20 °C. The reaction was performed under pseudo-first order conditions, and the rate constants were determined by fitting to a single exponential function using built-in software. The association rate constant (kon) and dissociation rate constant (koff) were determined from the slope and the y axis intercept, respectively, in the plot of the observed rates versus isocyanide concentrations.

Activity Measurements

End-point assays were performed in the cooling bath maintained at −7 °C by a Eulabo F 13 temperature controller. The assay mixture contained 470 μm GTP, 7 mm MgCl2, 50 mm NaCl, 10% ethylene glycol, and an appropriate amount of the enzyme solution in 150 μl of 40 mm TEA buffer. When desired, 104 μm YC-1 or 37 μm BAY41–2272 was added to the reaction mixture supplemented with 4% DMF to maintain the solubility of YC-1 or BAY41–2272. The mixtures were equilibrated in a septum-sealed anaerobic reaction vial with 2 atmospheres of O2 or N2. Reactions were started by the addition of 1.5 μm native or deuteroheme-substituted sGC and conducted at −7 °C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 5 μl of 30% acetic acid. The amount of cGMP formed was quantified by analysis on a C18 high performance liquid chromatography column equilibrated with 20 mm potassium phosphate buffer containing 10% methanol at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min.

Oxidation-Reduction (Redox) Potential Measurements

Spectroelectrochemical apparatus originally designed by Tsujimura et al. (29) was modified to enable direct monitoring of the redox potential with a platinum indicator electrode. An anaerobic 1-cm path length cuvette was used with a septum-capped port for injection and a female ground glass joint at the top that fitted to a male joint of a micro combined electrode, EA 234 (Metrohm, Herisau, Switzerland). A platinum mesh electrode (52 mesh, 8 × 10 mm) and platinum wire electrode (0.6-mm diameter) were also fixed on the inside walls of the cuvette to act as working and counter electrodes, respectively, in three-electrode potentiostat system. The combined electrode comprised a platinum indicator and Ag+/AgCl reference electrode that was connected to a pH meter, model Accumet AR15 (Fisher), to directly monitor the electrode potentials. After the buffer solution containing mediators (1.6 ml) was introduced into the spectroelectrochemical cuvette, the combined electrode was attached to the cuvette by fitting the joints, thereby making an air-tight seal. The solution was purged with purified N2 for 10 min. Then, the concentrated protein sample was introduced into the cuvette through the rubber septum cap. The cuvette was then placed in a temperature-controlled cell holder. The solution was constantly stirred with a magnetic stirrer during data collection. The desired redox levels of the protein sample were maintained by coulometric generation of mediator-titrant that was controlled by the three-electrode potentiostat system. The potential control by the three-electrode system was achieved by using a potentiostat, model HA-151A (Hokuto Denko Co., Tokyo, Japan). Redox potentials are quoted relative to the normal hydrogen electrode. The mediators used were 33 μm Ru(NH3)6Cl3, 33 μm p-benzoquinone, 10 μm toluylene blue, and 20 μm 3′-chloroindophenol. Dithiothreitol included in the stored sGC solution was removed by passing through a Superdex 200HR column (GE Healthcare) to avoid undesired redox reactions.

Reagents

GTP, t-butyl isocyanide, and isopropyl isocyanide were purchased from Sigma). YC-1 was purchased from ALEXIS (San Diego, CA). Other chemicals, purchased from Wako Chemicals Co. (Tokyo, Japan), were of the highest commercial grade.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

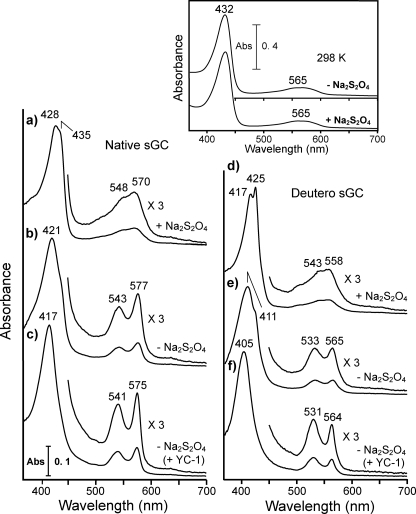

Detection and Characterization of the Oxy Form at Low Temperature

We observed that the yellowish-red-colored sGC preparation in the air-saturated buffer changed to brilliant red upon freezing in liquid N2, suggesting formation of a low spin heme. We analyzed the temperature-dependent change by low temperature optical spectroscopy at 77 K. Under anaerobic conditions, in which dissolved O2 was removed by Na2S2O4, the enzyme exhibited a spectrum corresponding to a high spin heme with the Soret band at ∼430 nm and a broad band centered at 560 nm in the visible region at 77 K (Fig. 1a). By contrast, the spectrum of sGC in air-saturated buffer (i.e. in the absence of Na2S2O4) at 77 K displayed well resolved α and β bands at 543 and 577 nm, respectively, accompanied by blue shift of the Soret band to 421 nm (Fig. 1b). Such distinct O2-dependent spectral changes were not observed at ambient temperature (298 K) where sGC exhibited a spectrum typical of ferrous high spin heme both in the presence and absence of Na2S2O4 at 298 K (inset of Fig. 1). The new species did not exhibit EPR signals assignable to ferric heme iron at either 15 and 5K. These findings together indicate that the species is in a ferrous low spin state and may be assigned to an oxy form of sGC based on the spectral similarities with that of oxyhemoglobin and the absolute requirement of O2 for its formation. Hereafter, we interpret experimental results by assuming that the ferrous heme iron in the enzyme is capable of binding O2 like the cobalt-substituted enzyme.

FIGURE 1.

Low temperature optical spectra of sGC. Optical spectra of native sGC (7.1 μm) at 77 K are summarized in the left panel. Trace a, native ferrous sGC in an anaerobic buffer, in which dissolved O2 was removed by the addition of Na2S2O4, was frozen at 77 K, and then the spectrum was recorded. Trace b, shown is the spectrum of native ferrous sGC in the air-saturated buffer. Trace c, shown is native ferrous sGC in the air-saturated buffer containing YC-1 (104 μm). Spectra of deuteroheme-substituted enzyme at 77 K are shown in the right panel. Trace d, shown is deuteroheme-substituted sGC in the anaerobic buffer with Na2S2O4. Trace e, shown is deuteroheme-substituted sGC in the air-saturated buffer. Trace d, shown is deuteroheme-substituted sGC in the air-saturated buffer containing YC-1 (104 μm). The buffer used was 40 mm TEA, pH 7.5, containing 5% (v/v) ethylene glycol and 50 mm NaCl. In traces c and f, 4% (v/v) DMF was supplemented in the above buffer to maintain the solubility of YC-1. The addition of DMF did not changed the spectral features both in anaerobic and aerobic conditions. In the inset, optical spectra of native sGC at 298 K in the presence and absence of Na2S2O4 are shown.

Although we have no available data to argue the mechanism of the formation, it is clear that the oxy form is produced in a course of freezing. The putative oxy form exhibited a somewhat broad Soret band with an obvious shoulder at around 430 nm and with a significant red-shifted Soret peak position in comparison with the Soret peak (417 nm) of oxyhemoglobin (Fig. 1b). These spectral properties suggested that the formation of the oxy form was incomplete because of the low affinity of the enzyme-heme for O2. Likewise, complete formation of the oxy form was not observed for deuteroheme-substituted sGC despite the large increase in O2 affinity by heme substitution as shown for myoglobin and hemoglobin (30, 31) (Fig. 1e). Therefore, it is unlikely that the incomplete O2 occupation is due to the low O2 affinity of the enzyme-heme. The complete formation of the oxy form was achieved by the addition of YC-1, as shown by a blue shift of the Soret band and intensified α and β bands (Fig. 1, c and f). These findings seem to indicate that YC-1 converts the O2-insensitive conformation to an O2 binding conformation.

We attempted to detect O2 ligation at the axial position of the heme by resonance Raman spectroscopy at 80 K. Oxyhemoglobin used as control exhibited a ν4 Raman band at 1380 cm−1 and a ν3 band at 1511 cm−1 characteristic of 6-coordinate low spin oxy heme (data not shown). Unlike hemoglobin, sGC frozen at 80K in the air-saturated buffer exhibited only 5-coordinate high spin bands at 1358 and 1476 cm−1 without showing any 6-coordinate low spin Raman bands either in the presence and absence of YC-1 (data not shown). We interpreted these spectral characteristics to be caused by conversion of the 6-coordinate oxy heme to 5-coordinate heme as a result of photo-dissociation of the bound O2. Thus, it was not possible to identify O2 ligation by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Next, we tried to detect ligation of O2 at the metal center using Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted enzyme.

We have reported that the Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted sGC has a weak Co2+-His bond and produces 5-coordinate NO complex like the native sGC (14). The present experiments further established that the metal substitution has no effect on the structure as well as catalytic properties of the enzyme, because there are no significant differences in the catalytic and the nucleotide binding properties and in the subunit structure and protein surface charges between the native and the Co-substituted enzymes (supplemental Figs. 1 and 2).

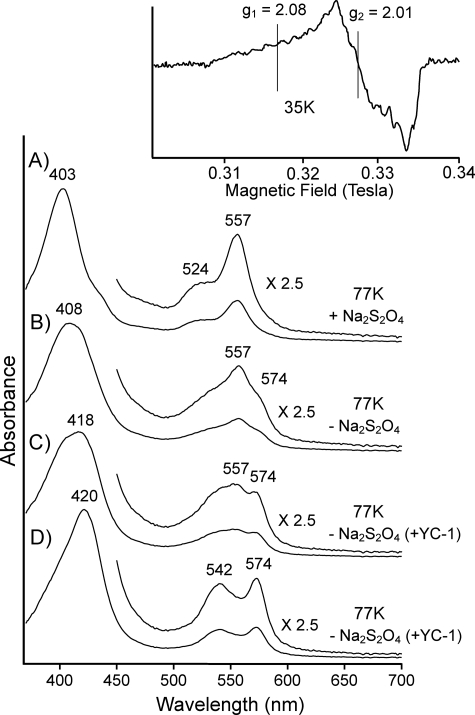

The optical spectrum of Co2+-proto sGC measured at 77 K in the presence of Na2S2O4 showed a Soret band at 403 nm and 524- and 557-nm bands in the visible region (Fig. 2A). When frozen in the air-saturated buffer, the 557-nm band of Co2+-protoporphyrin sGC was significantly decreased in intensity with an appearance of a new band at 574-nm and a significant red shift of the Soret band (Fig. 2B). The addition of YC-1 augmented the O2-dependent spectral change (Fig. 2C). In the O2-saturated buffer supplemented with YC-1, the spectrum converted to that of a single species with 420, 542, and 574 bands (Fig. 2D). These spectral features essentially agree with those of oxy Co-proto myoglobin (32). The species showed a free radical type EPR signal with hyperfine structure at g1 ∼ 2.08, which results from a coupling of unpaired electron to the Co nucleus (inset of Fig. 2). This is conclusive evidence for the formation of the oxy form (Co3+- O2−) of cobalt-porphyrin (33, 34). Co2+-mesoporphyrin sGC also exhibited similar O2-dependent spectral changes (supplemental Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

Low temperature optical spectra of cobalt protoporphyrin-substituted sGC. Trace A, Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted sGC in the anaerobic buffer in which dissolved O2 was removed by Na2S2O4 was frozen at 77 K, and then the spectrum was taken. Trace B, the spectrum of Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted sGC in the air-saturated buffer is shown. Trace C, the spectrum of Co2+-protoporphyrin sGC in the air-saturated buffer containing YC-1(104 μm) is shown. Trace D, the spectrum of Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted sGC in the O2-saurated buffer containing YC-1(104 μm) is shown. The buffer used was 40 mm TEA, pH 7.5, containing 5% (v/v) ethylene glycol and 50 mm NaCl. Inset, X-band (9.22 GHz) EPR spectrum of Co2+-protoporphyrin-substituted sGC in the O2-saturated buffer was taken at 35 K and by 100 K Hz field modulation with 1-millitesla width.

The coordination structures of the enzyme-heme in the unliganded, O2-bound, and CO-bound states were examined by the iron K-edge EXAFS. The k3-weighted EXAFS and the corresponding Fourier transforms are summarized in Fig. 3. To fit the experimental data, His, His and O2, and His and CO were employed as the axial ligands for the ferrous, the O2-bound, and the CO-bound hemes, respectively. The atomic coordination of corresponding myoglobin derivatives were employed as a starting model of the curve fitting. The structural parameters that satisfy the raw data by these approaches are summarized in Table 1. EXAFS of the unliganded ferrous sGC, obtained in the presence of Na2S2O4 (spectrum A in the left panel Fig. 3), was similar to that of deoxymyoglobin (28, 35). The iron in the unliganded ferrous sGC was displaced relative to the heme plane (Fe2+-Ct, distance between Fe2+ and porphyrin plane center) by 0.56 Å, like deoxymyoglobin (Table 1). The displacement is characteristic of high spin heme, because the high spin heme iron cannot be forced into the porphyrin plane due to the large covalent radius of high spin iron.

FIGURE 3.

k3 EXAFS spectra and their Fourier transforms of sGC. EXAFS spectra and their Fourier transforms (FT) were depicted in the left and the right panels, respectively. Traces A and a were in the presence of Na2S2O4. Traces B and b were in the presence of O2. Traces C and c were in the presence of CO. The buffer used was 40 mm TEA, pH 7.5, containing 5% (v/v) ethylene glycol and 50 mm NaCl. The enzyme concentration was 470 μm as heme. The solid lines indicate the observed EXAFS and Fourier transforms, and the dashed lines depicted simulation curves. The analyses incorporate multiple scattering from the outer shell atoms of the porphyrin ring and axial ligand molecules. Other details including refinement of data are described elsewhere (26–28).

TABLE 1.

Iron-ligand distances for soluble guanylate cyclase and myoglobin in their unliganded, O2, and CO forms estimated by EXAFS

The parameters used to simulate the K-edge EXAFS are principally the same as those by Binsted et. al. (26). Distances (R) and Debye-Waller terms of the ligand atom coordinating iron (2σ2) are included in the table. The abbreviations used are: Fe2+-Ct, distance of iron from the porphyrin plane center (magnitude of iron displacement); Fe2+-Npyr, bond distance between iron and porphyrin nitrogen atom; Fe2+-Nim, bond distance between iron and proximal His imidazole nitrogen atom; Fe2+-L, bond distance between iron and sixth ligand.

| Fe2+-ligand site | Fe2+ |

Fe2+-O2 |

Fe2+-CO |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 2σ2 | R | 2σ2 | R | 2σ2 | |

| Å | Å2 | Å | Å2 | Å | Å2 | |

| sGC | ||||||

| Fe2+-Ct | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.13 | |||

| Fe2+-Npyr | 2.09 | 0.004 | 2.09 | 0.002 | 2.05 | 0.003 |

| Fe2+-Nim | 2.10 | 0.005 | 2.13 | 0.006 | 2.05 | 0.002 |

| Fe2+-L | 1.89 | 0.004 | 1.85 | 0.004 | ||

| Myoglobin | ||||||

| Fe2+-Ct | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |||

| Fe2+-Npyr | 2.05 | 0.004 | 1.99 | 0.002 | 1.99 | 0.004 |

| Fe2+-Nim | 2.11 | 0.003 | 2.02 | 0.005 | 2.09 | 0.003 |

| Fe2+-L | 1.85 | 0.004 | 1.81 | 0.003 | ||

It is generally accepted that the Fe2+-His bond strength of sGC is weaker than that of myoglobin due to strain at the heme center (13, 14, 17, 36). Although the difference in the Fe2+-His bond strength between sGC and myoglobin was thought to be reflected in the Fe2+-His bond distance, the Fe2+-His bond distance observed in unliganded sGC essentially agreed with that of deoxymyoglobin (Table 1). The discrepancy may be explained by the tilting of the Fe2+-imidazole nitrogen bond from the heme normal, because such a distortion also weakens the Fe2+-His bond strength probably by decreasing π-bond interaction between iron dπ-orbital and imidazole nitrogen pπ-orbital.

EXAFS of sGC in the presence and absence of O2 were different, indicating binding of exogenous ligand at the axial position (spectrum B in the left panel of Fig. 3). Placing O2 at the 6th position of the heme using the parameters listed in Table 1, the heme iron was found to still bind the proximal His with a bond distance of 2.13 Å (Table 1). The iron displacement from the heme plane was much reduced upon placing O2 on the heme iron (0.09 Å) (Table 1). These results showed that the proximal His moved toward the heme plane along with the movement of the heme iron to produce the 6-coordinate oxy form, and therefore, the low affinity for O2 may be not caused by cleavage of the Fe2+-His bond. In the case of the CO complex, iron displacement of the CO complex was 0.13 Å. The value was somewhat larger than that of the corresponding derivative of myoglobin (Fig. 3 and Table 1), but these values fall in the range of a low spin iron.

To characterize the distal heme pocket structure, we focused on the bond distance and angle of Fe2+-ligand coordination, which were obtained with multiple scattering analyses of a limited narrow k range EXAFS (3–13 Å−1) (28). The geometries of sGC-ligand complexes are Fe2+-O2 bond distance = 1.89 Å and Fe2+-O-O bond angle = 120° for the oxy form, and Fe2+-CO bond distance = 1.85 Å and Fe2+-C-O bond angle = 171 ° for the CO form. The coordination geometry for myoglobin obtained by the present curve fitting procedure was 1.85 Å (bond distance) and 104° (bond angle) for the O2 form and 1.81 Å and 149° for the CO form. These values for myoglobin essentially agreed with those obtained by x-ray crystallographic analyses (37, 38). The present method for data analyses is useful for estimating iron-ligand geometry, although there is uncertainty in bond angle determination of ∼10°, including absolute and fitting errors (28, 39). Therefore, the EXAFS studies on sGC indicate that the CO moiety of the Fe2+-CO unit binds to the heme iron with a nearly linear geometry. Such geometry implies no steric protein effect on the distal side of the heme. Conversely, O2 seems to accommodate on the distal pocket with intrinsically bent Fe2+-O2 structure.

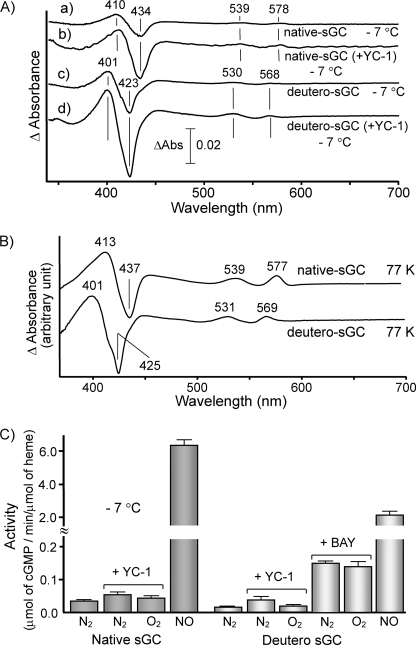

To establish whether the ligation of O2 affects the cyclase activity, we attempted to detect the oxy form under fluid conditions. In these experiments the formation of the oxy form was followed by the difference spectra against the spectrum in the presence of N2. At −7 °C, the difference spectra exhibited a 410-nm peak and a 434-nm trough in the Soret region and peaks at 539 and 578 nm in the visible region (trace a in Fig. 4A). The intensity of the 410-nm peak in the difference spectrum significantly increased in the presence of YC-1 (trace b in Fig. 4A). The spectral species formed under an atmosphere of O2 was assignable to an oxy form, because these peak and trough positions were essentially the same as those in the difference spectrum at 77 K (Fig. 4B). The amount of oxy form produced at −7 °C was estimated to be only 3% of total protein even in the presence of YC-1, based on the pure oxy form obtained arithmetically as described below. The formation of oxy form was temperature-dependent and significantly decreased upon raising the temperature to 3 °C (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Difference spectra of native and deuteroheme-substituted sGC between anaerobic and aerobic conditions and their cyclase activities at low temperature. In A, the difference spectra between O2 and N2 atmosphere under fluid conditions were summarized. The enzyme samples and temperature are indicated in the figure. The enzyme concentrations were 15.1 μm in both the native and the substituted enzymes. Traces a and b were for native sGC, and traces c and d were for deuteroheme-substituted sGC. In B, the difference spectra between O2 and N2 atmosphere under frozen conditions at 77 K are illustrated. The difference spectra shown were obtained by subtracting the spectrum under N2 atmosphere from that under O2 atmosphere. In C, activities of native and deuteroheme-substituted enzymes were assayed in 40 mm TEA, pH 7.5, containing 10% ethylene glycol, 50 mm NaCl, 7 mm MgCl2, and 0.47 mm GTP. When the addition of YC-1 (104 μm) or BAY 41–2272 (40 μm) was desired, 4% DMF was supplemented to the above buffer to maintain the solubility. The effect of DMF on the basal and NO-stimulated activities was negligible under the experimental conditions.

Deuteroheme substitution has been known to increase O2 affinity (30, 31). As anticipated, the degree of oxy form formed at −7 °C was greater than that of the native enzyme (trace c in Fig. 4A). Nevertheless, the yield of oxy form for the deuteroheme-substituted enzyme was still only ∼4%. YC-1 significantly increased the formation of the oxy form in the deuteroheme-substituted enzyme to approximately ∼7% of total protein (trace d in Fig. 4A).

The effect of O2 on cyclase activity was examined in the presence of YC-1 at −7 °C (Fig. 4C). The addition of NO resulted in 120-fold activation of the native enzyme, whereas the presence of O2 did not appear to enhance the cyclase activity in the absence and presence of YC-1. Similar results were also observed for the deuteroheme-substituted enzyme, where the presence of O2 did not enhance the cyclase activity of the substituted-enzyme in the presence of YC-1 and its derivative, BAY 41–2272 (3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-3′-furyl)-1-benzylindazole) (Fig. 4C). In this connection it is interesting to note that the cyclase activity catalyzed by Gcy-88E from Drosophila was not stimulated by CO, NO, and O2 (40). This enzyme formed stable 6-coordinate NO and O2 complex, unlike typical sGC. These results together with the present data suggest that the ligand-dependent stimulation may be closely coupled with the Fe2+-His bond strength, although the detailed mechanism remains to be elucidated.

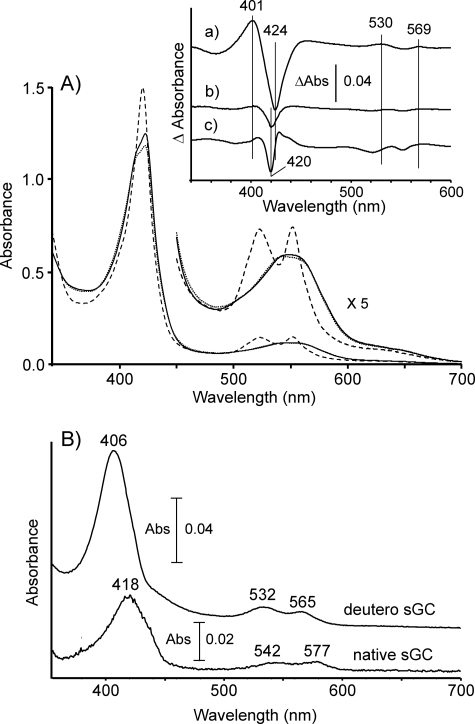

To ask whether the exogenous heme-ligand can prevent O2 binding to the enzyme-heme, we examined the inhibitory effect on the O2 binding. As shown in Fig. 5A, the O2-dependent spectral change in the presence of BAY 41–2272 yielded the largest change observed so far (compare the solid line with the dotted line). In contrast, the O2-dependent spectral change was noted to be much reduced when isopropyl isocyanide was included in the mixture (compare trace a with trace b in the inset of Fig. 5A). The difference spectrum (trace b) does not agree with trace a in the entire spectral region. Although the trace b displayed the trough at 420 nm similar to that of trace c, the bandwidth of trace b was much larger than that of trace c, suggesting the displacement of the bound isocyanide by O2. The nearly identical result was also observed for native sGC in the reaction of the t-butyl isocyanide adduct with O2 (data not shown). These spectral features agreed with the view that isocyanide competed with the same site as O2.

FIGURE 5.

The effect of isocyanide on the O2 binding and the spectra of the complete oxy form. In A, the optical spectra of deuteroheme-substituted sGC in the presence of BAY 41–2272 were illustrated. The spectra shown by a solid and a dotted line are the spectrum of the ferrous enzyme in the N2-saturated and in the O2-saturated buffer, respectively. The spectrum shown by the broken line was that in the presence of isopropyl isocyanide (170 μm). The buffer used was 40 mm TEA buffer, pH 7.5, containing 10% ethylene glycol, 50 mm NaCl, 4% DMF, and 37 μm BAY 41–2272. The difference spectra were summarized in the inset, where trace a is a difference spectrum by subtracting the spectrum in the N2-saturated buffer from that in the O2-saturated buffer, and trace b was obtained by subtracting the spectrum in the N2 buffer from that in the O2 buffer, of which buffers contained isopropyl isocyanide (170 μm). Trace c is the difference spectrum by subtracting the spectrum of the isopropyl isocyanide adduct from that of the ferrous enzyme, which is illustrated in the scale. In B, the spectrum of the complete oxy form was arithmetically obtained by subtracting the ferrous spectrum multiplied by a factor from the spectrum in the O2-saturated buffer. The data used for the native enzyme were the absolute spectra (in N2 and O2) used to generate trace b in Fig. 4A and for the deuteroheme-substituted enzyme the spectra in Fig. 5A. The subtractions of the ferrous enzyme multiplied by 0.97 and 0.89 could satisfactorily eliminate the residual ferrous enzyme for the native and the deuteroheme enzymes, respectively.

The spectrum of the complete oxy form could be arithmetically obtained by subtracting the ferrous-enzyme spectrum multiplied by a factor from the spectrum in the O2-saturated buffer. In the presence of YC-1 and BAY 41–2272, as shown in Fig. 5A, the subtractions of the ferrous enzyme multiplied by 0.97 and 0.89 could satisfactorily eliminate the residual ferrous enzyme for the native and the deuteroheme enzyme, respectively. The resultant arithmetic spectra (Fig. 5B) agree with those of the oxy form obtained at 77K (Fig. 1). On the basis of these results together with EXAFS and other optical spectral studies described in this paper, we finally conclude that the heme in sGC is capable of binding O2.

Protein Effects on Ligand Binding

Using the systematic kinetic data, Mims et al. (41) assessed the protein effects on the ligand binding of myoglobin. The effects are summarized as (i) distal steric hindrance to restrict the approach of the ligand to its final position and (ii) a protein proximal effect that controls successive bond formation of the iron with ligand on the distal side. When the bond between iron and ligand (such as O2) is generated, the distal His residue forms a hydrogen bond with the bound O2 to stabilize the O2 complex. These mechanisms, which were originally formulated for myoglobin, provide key clues in understanding the ligand binding of other hemoproteins.

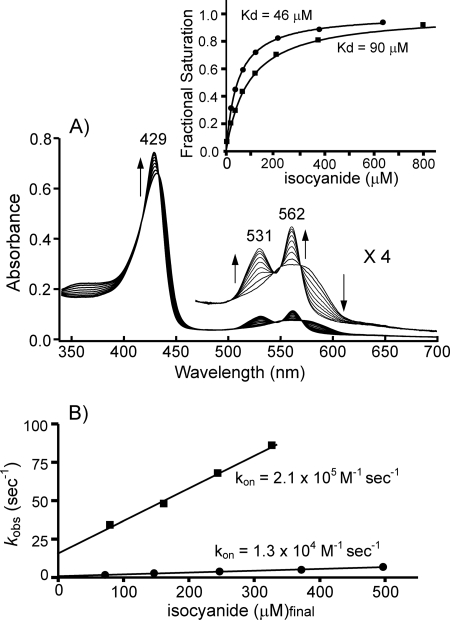

We have assessed the distal steric protein effect by analyzing the reaction of the ferrous heme iron with alkyl isocyanides. As shown in Fig. 6A, careful titration with t-butyl isocyanide showed that the unliganded ferrous sGC converted to the isocyanide adduct through one set of isosbestic points. The binding of isopropyl isocyanide also yielded nearly identical species (data not shown). The optical spectra of these alkyl isocyanide adducts were essentially the same as those of the corresponding isocyanide adducts of myoglobin, demonstrating that the isocyanide adducts of sGC were in a six-coordinate low spin state (42). The dissociation constants (Kd) calculated were 46 and 90 μm for t-butyl isocyanide and isopropyl isocyanide (inset of Fig. 6), respectively, indicating that the affinity for t-butyl isocyanide is significantly higher by comparison to that for isopropyl isocyanide. In general, the affinities of isocyanide for the hemoproteins decreased with increasing size of alkyl group in the isocyanide molecule (41). In contrast, sGC exhibited a higher affinity for isocyanide with a larger alkyl group. The anomalous property has also been noted for human hemeoxygenase (43). The association rates of isocyanides with the ferrous sGC decreased with increasing size of alkyl group in the isocyanide molecule. The rates are 10-fold faster than the formation of the corresponding isocyanide adducts of myoglobin (Fig. 6B and Table 2) and nearly equivalent to those of leghemoglobin (44), which are the highest among the globin family. Taking into consideration these findings, we propose that there is no substantial resistance to the binding of bulky isocyanides with sGC, in contrast to myoglobin, supporting the previous result (45).

FIGURE 6.

Equilibrium binding and kinetic analyses of alkyl isocyanide binding. A, shown are changes in the absorption spectra of sGC during titration with t-butyl isocyanide. B, kobs values obtained from stopped-flow traces were plotted against the final concentration of isocyanide after mixing. Closed circles (●) are data from t-butyl isocyanide, and closed squares (■) are data from isopropyl isocyanide. In the inset, isocyanide binding curves are plotted as the fractional saturation versus the effective concentration of isocyanide. Solid lines depicted simulated lines obtained by nonlinear regression analyses. Equilibrium and kinetic binding experiments were done at 20 °C. Other details are described under “Experimental Procedures.”

TABLE 2.

Ligand binding properties of soluble guanylate cyclase, sperm whale myoglobin, and soybean leghemoglobin

| Kd | kon | Koff | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | m−1s−1 | s−1 | ||

| Soluble guanylate cyclase | ||||

| CO | 298a | 3.6 × 104 | 10.7 | This study |

| Isopropyl isocyanide | 90 (81a) | 2.0 × 105 | 16.1 | This study |

| t-Butyl isocyanide | 48 (61a) | 1.3 × 104 | 0.80 | This study |

| Sperm whale myoglobin | ||||

| CO | 0.03a | 5.0 × 105 | 0.015 | 41 |

| Isopropyl isocyanide | 73 (87a) | 7.5 × 103 | 0.65 | This study |

| t-Butyl isocyanide | 836 (803a) | 1.5 × 103 | 1.20 | This study |

| Soybean leghemoglobin | ||||

| CO | 0.0013a | 1.3 × 107 | 0.016 | 44 |

| Isopropyl isocyanide | 0.0073a | 4.1 × 105 | 0.0030 | 44 |

| t-Butyl isocyanide | 0.082a | 2.2 × 104 | 0.0018 | 44 |

a Calculated as koff/kon.

In accordance with a previous report (22), sGC binds CO with an association rate constant of 3.6 × 104 m−1 s−1, which is particularly slow among 5-coordinate high spin hemoproteins (Table 2). The most striking feature is that the association rate for isopropyl isocyanide was approximately one order of magnitude faster than that for CO binding, irrespective of the larger size of the isocyanide by comparison to CO (Table 2). These findings strongly suggest that sGC permits easy access for small ligands, such as CO and O2, to the coordination position. Therefore, the formation of the coordinate bond dominates the kinetics of association, accentuating the significance of the proximal protein effect.

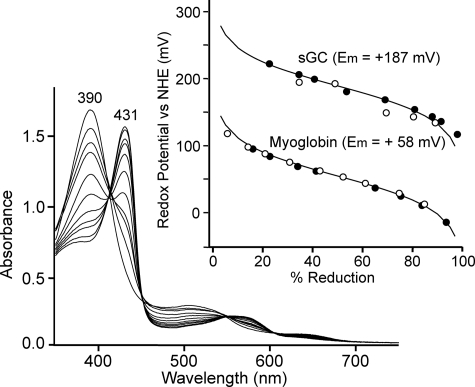

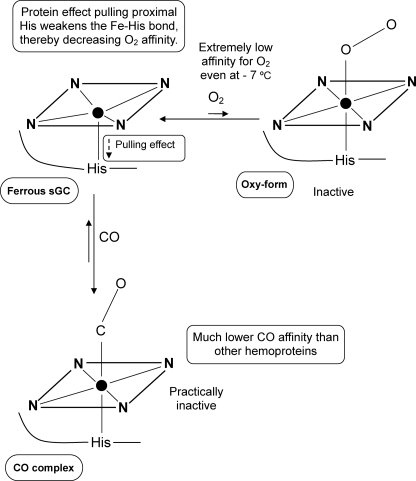

Based on quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical analyses, it was proposed that the degree of electron density on the heme iron might be controlled by the protein proximal effect (46). This effect on the proximal side modulates the Fe2+-ligand bond formation on the distal side. For instance, when the Fe2+-proximal His bond is weakened by strain imposed on the bond, the electron density on the heme iron is reduced relative to that of the Fe2+-His bond without strain. This might reduce the electron donation from the iron to ligand such as O2, resulting in the weakening of the Fe2+-O2 bond strength (46). Thus, a weak Fe2+-His bond correlates with a weak Fe2+-O2 bond and vice versa. Such a protein effect, referred to as a positive trans effect, accounts for the unique character of the CO and O2 binding characteristics of the iron-porphyrin complexes (47–50). The proximal effect derived by strain on the Fe2+-His bond probably affects redox potential of the heme, because the decrease in electron density at the ferrous heme makes it more difficult to remove an electron (51). For example, T-state hemoglobin with a more strained Fe2+-His bond and lower O2 affinity relative to R-state hemoglobin exhibited significantly higher midpoint potentials of the heme than R-state hemoglobin (52). The redox potential measurements of sperm whale myoglobin and sGC indicated that the electrochemical titration curves fitted to a Nernst equation with n = 1 in both hemoproteins (Fig. 7). The ferric-ferrous couple of myoglobin gave the midpoint potential of +58 mV, in reasonable agreement with the reported value. The midpoint potential of sGC, +187 mV, was considerably higher than that of myoglobin. It should be noted that the measured value was the most positive among high spin protoheme-containing hemoproteins, presumably because the electron density of the heme in sGC is significantly reduced by the protein proximal effect. Based on the above considerations and EXAFS data, the significance of the proximal protein effect on the ligand binding was noted as summarized in Fig. 8.

FIGURE 7.

Anaerobic redox titration of sGC. The reaction mixture contained 15 μm of sGC or sperm whale myoglobin and a mixture of mediators in 50 mm Hepes buffer at pH 7.5 containing 50 mm KCl and 5% ethylene glycol. The final volume was 1.6 ml. The cuvette was kept under an anaerobic atmosphere of N2, at 20 °C. The desired redox levels were maintained by coulometric generation of mediator-titrant, of which potentials were controlled by a three-electrode system as described in under “Experimental Procedures.” After the reaction was achieved to redox equilibrium, spectra were recorded. Redox potentials were determined by both the reductive (○) and oxidative (●) titrations, in which the potentials were directly monitored by a combined microelectrode. In the inset, redox potentials were plotted against the degree of reduction. Solid lines denote the theoretical lines calculated according to Nernst equation with n = 1. Other details were described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mediators used were 17 μm pyocyanine, 2 μm 2,6-dichloroindophenol, 6.6 μm toluylene blue, and 33 μm Ru(NH3)6Cl3 for myoglobin and 33 μm p-benzoquinone, 33 μm Ru(NH3)6Cl3, 10 μm toluylene blue, and 20 μm 3′-chloroindophenol for sGC. NHE denotes Normal Hydrogen Electrode.

FIGURE 8.

Model proposed for bindings of the ferrous sGC with O2 and CO. The heme coordination structures were depicted based on EXAFS data (Table 1). Closed circles illustrated in the center of heme denote ferrous iron atom. The weak Fe2+-His bond in the ferrous enzyme may decrease charge density on the heme iron, thereby decreasing the O2 affinity and elevating the redox potential of the heme.

In summary, we have detected and characterized the oxy form of sGC. To assess the crucial determinant(s) for the low O2 affinity of sGC, we have analyzed the coordination structure by EXAFS. Our results indicate that the low affinity for O2 is not caused by cleavage of the Fe2+-proximal His bond. Among protein effects to regulate the reactivity of heme, the distal steric hindrance could be excluded based on the kinetic studies. The critical factor that may contribute to the low O2 affinity is the protein proximal effect, a regulatory effect caused by the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond. Measurement of the midpoint potential of the heme also highlights the significance of the protein proximal effect in terms of the unique low O2 affinity of sGC. Based on the findings described in this paper, we to propose that the weak Fe2+-proximal His bond is a key factor in regulating the reactivity of the heme in sGC along with the hydrogen bond interaction in the distal pocket, which was identified previously by mutational analysis (20).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by Frontier Project “Life Adaptation Strategies to Environmental Changes” of Rikkyo University and grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Culture, Education, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to R. M.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- sGC

- soluble guanylate cyclase

- Kd

- dissociation constant

- kon

- association rate constant

- koff

- dissociation rate constant

- EXAFS

- extended x-ray absorption fine structure

- DMF

- dimethylformamide

- TEA

- triethanolamine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Furchgott R. F., Zawadzki J. V. (1980) Nature 288, 373–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ignarro L. J., Kadowitz P. J. (1985) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 25, 171–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waldman S. A., Murad F. (1987) Pharmacol. Rev. 39, 163–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garthwaite J., Charles S. L., Chess-Williams R. (1988) Nature 336, 385–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bredt D. S., Snyder S. H. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 9030–9033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moncada S., Higgs E. A. (1991) Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 21, 361–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Verma A., Hirsch D. J., Glatt C. E., Ronnett G. V., Snyder S. H. (1993) Science 259, 381–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kamisaki Y., Saheki S., Nakane M., Palmieri J. A., Kuno T., Chang B. Y., Waldman S. A., Murad F. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7236–7241 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stone J. R., Marletta M. A. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 5636–5640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Humbert P., Niroomand F., Fischer G., Mayer B., Koesling D., Hinsch K. D., Gausepohl H., Frank R., Schultz G., Böhme E. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 190, 273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wedel B., Humbert P., Harteneck C., Foerster J., Malkewitz J., Böhme E., Schultz G., Koesling D. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 2592–2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao Y., Marletta M. A. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 15959–15964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deinum G., Stone J. R., Babcock G. T., Marletta M. A. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 1540–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Makino R., Matsuda H., Obayashi E., Shiro Y., Iizuka T., Hori H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7714–7723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ignarro L. J., Wood K. S., Wolin M. S. (1982) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 2870–2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerzer R., Hofmann F., Schultz G. (1981) Eur. J. Biochem. 116, 479–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Makino R., Obayashi E., Homma N., Shiro Y., Hori H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11130–11137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nioche P., Berka V., Vipond J., Minton N., Tsai A. L., Raman C. S. (2004) Science 306, 1550–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pellicena P., Karow D. S., Boon E. M., Marletta M. A., Kuriyan J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 12854–12859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boon E. M., Huang S. H., Marletta M. A. (2005) Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hu X., Murata L. B., Weichsel A., Brailey J. L., Roberts S. A., Nighorn A., Montfort W. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20968–20977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin E., Berka V., Bogatenkova E., Murad F., Tsai A. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27836–27845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Derbyshire E. R., Deng S., Marletta M. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17471–17478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yazawa S., Tsuchiya H., Hori H., Makino R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21763–21770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hagihara B., Iizuka T. (1971) J. Biochem. 69, 355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Binsted N., Strange R. W., Hasnain S. S. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 12117–12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Obayashi E., Tsukamoto K., Adachi S., Takahashi S., Nomura M., Iizuka T., Shoun H., Shiro Y. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 7807–7816 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miyatake H., Mukai M., Adachi S., Nakamura H., Tamura K., Iizuka T., Shiro Y., Strange R. W., Hasnain S. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 23176–23184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsujimura S., Kuriyama A., Fujieda N., Kano K., Ikeda T. (2005) Anal. Biochem. 337, 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makino R., Yamazaki I. (1974) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 165, 485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seybert D. W., Moffat K., Gibson Q. H., Chang C. K. (1977) J. Biol. Chem. 252, 4225–4231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yonetani T., Yamamoto H., Woodrow G. V., 3rd (1974) J. Biol. Chem. 249, 682–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ikeda-Saito M., Iizuka T., Yamamoto H., Kayne F. J., Yonetani T. (1977) J. Biol. Chem. 252, 4882–4887 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hori H., Ikeda-Saito M., Yonetani T. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 3636–3642 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eisenberger P., Shulman R. G., Kincaid B. M., Brown G. S., Ogawa S. (1978) Nature 274, 30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stone J. R., Sands R. H., Dunham W. R., Marletta M. A. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 207, 572–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li T., Quillin M. L., Phillips G. N., Jr., Olson J. S. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 1433–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang F., Phillips G. N., Jr. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 256, 762–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rich A. M., Armstrong R. S., Ellis P. L., Lay P. A. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 10827–10836 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang S. H., Rio D. C., Marletta M. A. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 15115–15122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mims M. P., Porras A. G., Olson J. S., Noble R. W., Peterson J. A. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 14219–14232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Derbyshire E. R., Marletta M. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35741–35748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Evans J. P., Kandel S., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 8920–8928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stetzkowski F., Cassoly R., Banerjee R. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 11351–11356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Derbyshire E. R., Tran R., Mathies R. A., Marletta M. A. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 16257–16265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marti M. A., Crespo A., Capece L., Boechi L., Bikiel D. E., Scherlis D. A., Estrin D. A. (2006) J. Inorg. Biochem. 100, 761–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Collman J. P., Brauman J. I., Iverson B. L., Seeler J. L., Morris R. M., Gibson Q. M. (1983) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3052–3064 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oberting W. A., Kean R. T., Wever R., Babcock G. T. (1990) Inorg. Chem. 29, 2633–2645 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Traylor T. G., Duprat A. F., Sharma V. S. (1993) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 810–811 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gullotti M., Santagostini L., Monzani E., Casella L. (2007) Inorg. Chem. 46, 8971–8975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Falk. J. E. (1964) Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins, pp. 67–71, Elsevier Publishing Co., Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 52. Faulkner K. M., Bonaventura C., Crumbliss A. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13604–13612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.