Abstract

p97 is composed of two conserved AAA (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) domains, which form a tandem hexameric ring. We characterized the ATP hydrolysis mechanism of CDC-48.1, a p97 homolog of Caenorhabditis elegans. The ATPase activity of the N-terminal AAA domain was very low at physiological temperature, whereas the C-terminal AAA domain showed high ATPase activity in a coordinated fashion with positive cooperativity. The cooperativity and coordination are generated by different mechanisms because a noncooperative mutant still showed the coordination. Interestingly, the growth speed of yeast cells strongly related to the positive cooperativity rather than the ATPase activity itself, suggesting that the positive cooperativity is critical for the essential functions of p97.

Keywords: ATPases, C. elegans, Chaperone Chaperonin, Cooperativity, Yeast, AAA

Introduction

AAA6 (ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities) superfamily proteins use the chemical energy generated from ATP hydrolysis to induce conformational changes (1). This conformational change provides mechanical work on macromolecular substrates such as unfolding of substrate proteins, disassembly of protein complexes, and disaggregation of protein masses. AAA proteins are characterized by the presence of one (type I) or two (type II) conserved AAA domains, consisting of a Walker-type ATPase domain with the second region of homology (SRH), which is specifically conserved in AAA domains, followed by an α-helical C-domain (2). AAA domains generally form a ring-shaped hexamer, and thus, there are six and 12 ATPase active sites in the type I and type II AAA proteins, respectively. These ATPase active sites influence each other and/or cooperate to perform their biological activities.

p97 (also known as valosin-containing protein in mammals, Cdc48p in yeast, and CDC-48.1 and CDC-48.2 in Caenorhabditis elegans) is a highly conserved type II AAA protein. p97 plays essential roles in numerous cellular processes, including homotypic fusion of endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi membranes (3–6), endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (7–10), nuclear envelope reassembly (11), transcription activation (12), meiotic progression (13), and modification of protein aggregates (14). p97 is composed of an N-terminal regulatory domain followed by two AAA domains (D1 and D2), which forms a homo-hexameric tandem ring structure. Using mammalian p97, it has been shown that D2 mediates major ATPase activity, which is positively cooperative (15, 16). On the other hand, the role of D1 is under debate, except for the fact that the D1 ATPase activity is very low at physiological temperature. Some groups showed that any ATPase-deficient mutations in D1 affect neither the overall ATPase activity nor the function of p97 (15, 17, 18), whereas others showed that a mutation that causes a defect in ATP binding of D1 strongly reduces the overall ATPase activity (9, 16). We recently found, using the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that cells with Cdc48p mutants deficient in ATP binding of D1 are able to grow, suggesting that ATPase deficiency of D1 does not affect the vital D2 ATPase activity in terms of essentiality (19). In addition to the dispute on the D1 ATPase activity, the cooperative D2 ATPase machinery and its significance have not been clear.

We have purified recombinant CDC-48.1 of C. elegans, which showed substantial ATPase activity (14). In this study, a systematic analysis was performed to characterize the ATPase activity of D1 and D2 of CDC-48.1. Like mammalian p97, D2 but not D1 of CDC-48.1 showed strong ATPase activity with positive cooperativity at physiological temperature. In addition, we found that the ATPase activity itself and its cooperativity of D2 are differently affected by ATPase-deficient mutations in D1. Interestingly, magnitude of the cooperativity of D2 is well related to the growth rate of yeast cells. We propose that the positively cooperative D2 ATPase activity of p97, which is operated in a coordinated fashion, is critical for viability of the cell.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of CDC-48.1 Variants and ClpX

Plasmids expressing N-terminally His-tagged CDC-48.1 mutants were constructed using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. CDC-48.1 mutants were expressed in insect cells and purified as described previously (14). N-terminally His-tagged ClpX from Escherichia coli was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified as described previously (20).

ATPase Assay

ATPase activity was determined using the malachite green assay (21) as described previously (14). Alternatively, steady-state kinetic parameters of ATP hydrolysis were determined by the enzyme-coupled spectrophotometric assay (22) with minor modifications. The assay was performed in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 3 mm MgCl2, 30 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 50 mm KCl, 45% glycerol, 6 mm NADH, 30 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, and 25 units/ml each of pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase at room temperature. The absorbance of 340 nm was recorded every second in a 1-cm path length cuvette, and the rate of ATP hydrolysis was calculated using an extinction coefficient value of 6.22 mm−1 cm−1 for NADH.

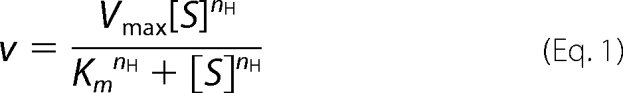

For estimating Hill coefficients, rates of ATP hydrolysis in various ATP concentrations were fitted to Equation 1.

|

Here, v represents the velocity of ATP hydrolysis, and Vmax is the maximal velocity, [S] denotes the molar concentration of ATP, Km are [S] where v is 50% of Vmax, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Yeast Strains

Yeast S. cerevisiae strains expressing a Cdc48p mutant under the control of the CDC48 promoter on a CEN plasmid with a chromosomal deletion of the CDC48 gene were constructed as described previously (19). Growth rates were determined by measuring A600.

RESULTS

Rationale for Mutations

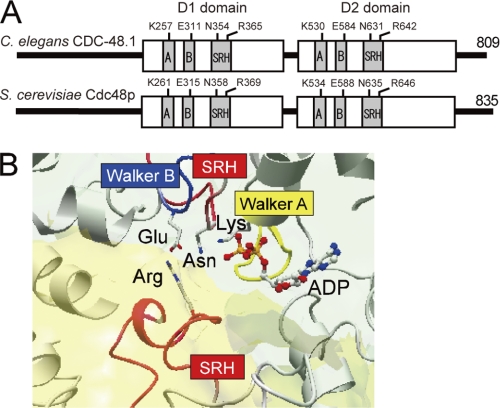

We generated a set of point mutants of either one or both of the two AAA ATPase domains of CDC-48.1 (Fig. 1A). Mutants defective in ATP binding were obtained by replacing the conserved Lys residues (Lys257 in D1 and Lys530 in D2) in the Walker A motifs with Ala. Mutants that allow ATP binding but are defective in hydrolysis were obtained by mutating the conserved Glu residues (Glu311 in D1 and Glu584 in D2) in the Walker B motifs to Gln. Conserved Asn (Sensor-1) and Arg (arginine finger) residues in the SRH interact with γ-phosphate of ATP in cis and in trans, respectively (Fig. 1B), and are required for ATP hydrolysis. We generated mutants in the Sensor-1 residues in D1 (N354A) and D2 (N631A) and in the arginine finger residues in D1 (R365A) and D2 (R642A). Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of CDC-48.1 with the mutation in the D2 Walker B motif, but not in the D2 Walker A motif, was changed upon nucleotide binding (supplemental Fig. S1), indicating that the mutants did work as predicted.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of p97. A, schematic representation of CDC-48.1 from C. elegans and Cdc48p from S. cerevisiae. Mutation sites in the Walker A (A) and B (B) motifs, and Sensor-1 and arginine finger in the SRH are shown. The N-terminal domain of yeast Cdc48p is longer than CDC-48.1 by four residues. B, the crystal structure of the active ATPase site of p97 D1 showing ADP bound at the interface of two protomers. The Walker A motif (yellow), the Walker B motif (blue), and the SRH (red) are shown. Residues involving ATP binding and hydrolysis are shown (sticks). Lys of the Walker A motif, Glu of the Walker B motif, and Asn of the SRH work in cis, whereas Arg of the SRH works in trans.

D1 ATPase Activity Is very Low at Physiological Temperature, but Nucleotide-dependent Conformations Affect D2 ATPase Activity

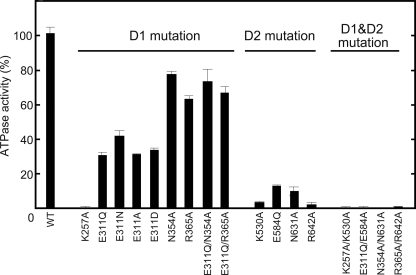

We first examined the basal ATPase activity of CDC-48.1 variants at 30 °C (21). We reported previously that wild type CDC-48.1 showed the ATPase activity of 437 nmol/mg/min at 30 °C (14). Mutant proteins harboring mutations on catalytic residues in both D1 and D2 (CDC-48.1K257A/K530A, CDC-48.1E311Q/E584Q, CDC-48.1N354A/N631A, and CDC-48.1R365A/R642A) exhibited nearly background ATPase activity (Fig. 2 and Table 1). On the other hand, mutants of D2 such as CDC-48.1K530A, CDC-48.1E584Q, CDC-48.1N631A, and CDC-48.1R642A, which have an ATPase-deficient D2 and thus exhibit only the D1 ATPase activity, showed very low but significant ATPase activity at 30 °C (Fig. 2 and Table 1), indicating that D1 has only low ATPase activity at physiological temperature.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of the ATPase activity of CDC-48.1 mutants. ATPase activity was measured at 30 °C by the malachite green assay. The ATPase activity of wild type CDC-48.1 was set to 100%. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three independent experiments.

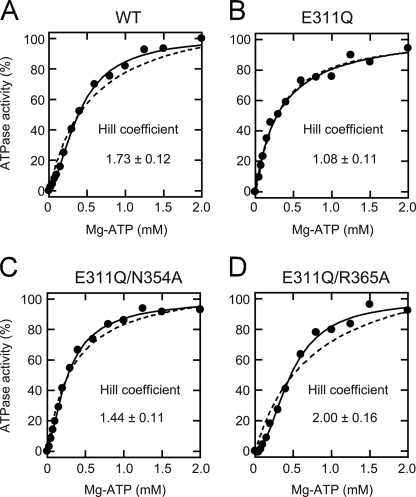

TABLE 1.

Correlation between the ATPase activity and growth rate

* n.d., not determined.

Mutants of D1 such as CDC-48.1K257A, CDC-48.1E311Q, CDC-48.1N354A, and CDC-48.1R365A, which have an ATPase-deficient D1 and thus exhibit only the D2 ATPase activity, showed different ATPase activity depending on the mutations (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The ATP binding-deficient Walker A mutation in D1 (K257A) completely diminished ATPase activity, suggesting that ATP binding to D1 is prerequisite for intrinsic ATPase activity of D2. The ATP hydrolysis-deficient Walker B mutant of D1 (CDC-48.1E311Q) showed significantly impaired ATPase activity (∼30%) relative to CDC-48.1WT, whereas SRH mutants of D1 (CDC-48.1N354A and CDC-48.1R365A) exhibited higher ATPase activity, which was ∼70% of CDC-48.1WT. Because the Walker B mutant likely stalls in an ATP-bound state due to the lack of the catalytic residue, it is possible that the ATP-bound conformation of D1 may inhibit the ATPase activity of D2. On the other hand, the mutations in Sensor-1 and the arginine finger of D1 did not significantly affect the D2 ATPase activity, even though these mutations also fix D1 in the ATP-bound form. The Sensor-1 and arginine finger residues interact with the γ-phosphate of bound ATP, which may generate a signal inhibiting the ATPase activity of D2. To test this possibility, we constructed double mutants, CDC-48.1E311Q/N354A and CDC-48.1E311Q/R365A. Introduction of an additional mutation in the D1 SRH restored the ATPase activity of the Walker B mutant comparable with that of the single SRH mutants (Fig. 2 and Table 1), indicating that the D1 SRH mutations compromise the defective effect of the D1 Walker B mutation. These results suggest that ATP-bound state of D1, which is sensed by the SRH residues, perturbs the normal D2 ATPase activity.

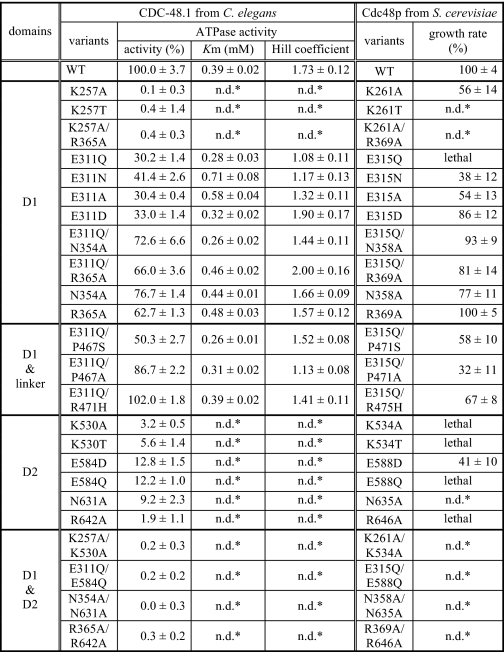

D1 also Affects Cooperativity of D2

Next, we investigated the kinetics of the D2 ATPase activity. To this end, initial velocity of ATP hydrolysis was measured as a function of the Mg2+-ATP concentration (22) at room temperature. Fitting Equation 1 described in the “Experimental Procedures” to the data for CDC-48.1WT gave a Hill coefficient of 1.73 ± 0.12 (Fig. 3A). The Hill coefficients of the D1 mutants, CDC-48.1N354A and CDC-48.1R365A, were calculated to be 1.66 ± 0.09 and 1.57 ± 0.12, respectively (Table 1). These results indicate that the D2 ATPase activity is positively cooperative. In contrast, the Hill coefficient of CDC-48.1E311Q was calculated to be 1.08 ± 0.11, indicating that the positive cooperativity of D2 is lost in this mutant (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, introduction of an additional mutation in the D1 SRH into CDC-48.1E311Q (CDC-48.1E311Q/N354A and CDC-48.1E311Q/R365A) restored the Hill coefficient to be 1.44 ± 0.11 and 2.00 ± 0.16, respectively (Fig. 3, C and D). These results suggest that sensing of the ATP bound to D1 by the SRH residues also perturbs the communication between D2 in a hexamer.

FIGURE 3.

Kinetic analysis of the ATPase activity of CDC-48.1 mutants. ATP hydrolysis rates of CDC-48.1WT (A), CDC-48.1E311Q (B), CDC-48.1E311Q/N354A (C), and CDC-48.1E311Q/R365A (D) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of ATP and magnesium chloride were measured at room temperature using the enzyme-coupled assay. The solid lines were obtained by a least-squares fit to the equation 1 as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and the kinetic parameters were calculated. The dashed lines are fitting curves when nH is fixed to 1.

Next, we tested whether the negative effect of the mutation in the D1 Walker B motif on D2 ATPase activity is limited to the substitution with Gln. CDC-48.1E311N, CDC-48.1E311A, and CDC-48.1E311D exhibited decreased ATPase activity similar to CDC-48.1E311Q (Fig. 2). In contrast to CDC-48.1E311Q, however, CDC-48.1E311N and CDC-48.1E311A showed quite weak but significant positive cooperativity. (Hill coefficients were 1.17 ± 0.13 and 1.32 ± 0.11, respectively.) Moreover, CDC-48.1E311D showed a much higher Hill coefficient (1.90 ± 0.17), which is comparable with that of the wild type protein. Taken together, it is indicated that the D1 ATPase mutations affect both the D2 ATPase activity and its cooperativity, but to different extents.

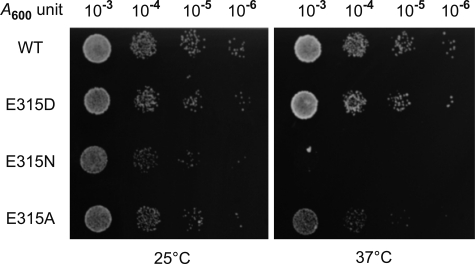

Positive Cooperativity of D2 Is Crucial for Essential Physiological Function(s) in Vivo

We have found that in the yeast S. cerevisiae, the E315Q mutation in D1 of Cdc48p, which corresponds to the E311Q mutation of CDC-48.1, is lethal, whereas another D1 Walker B mutation, E315D (E311D in CDC-48.1), is viable (Fig. 4) (19). The viability in our yeast system depends on the function of Cdc48p mutants because CDC48 is an essential gene, and each mutant cell expresses only a mutated Cdc48p instead of the wild type protein. To determine the difference, we compared ATPase features of purified CDC-48.1E311Q and CDC-48.1E311D. Both proteins showed similar ATPase activity (30.2% versus 33.0%), whereas the Hill coefficients representing the cooperativity were quite different (1.08 versus 1.90), suggesting the possibility that loss of the cooperativity but not decrease in D2 ATPase activity is the cause for the lethality. Because CDC-48.1 mutants with other substitutions at the same residue showed similar ATPase activity but different cooperativity (Table 1), we tested whether or not yeast cells expressing corresponding Cdc48p mutants grow. Yeast cells expressing Cdc48pE315N or Cdc48pE315A were viable at 25 °C, whereas significant growth defects were observed at 37 °C (Fig. 4). Thus, lowering the positive cooperativity of p97 seems to cause a growth defect.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of D1 Walker B mutations on the growth of S. cerevisiae. Yeast cells expressing wild type Cdc48p and mutant forms of Cdc48p as a sole Cdc48 copy were diluted in 10-fold increments, and 5 μl of each dilution (starting with the 0.001 A600 unit) were spotted onto SD medium lacking histidine. Cells were grown at 25 °C and 37 °C.

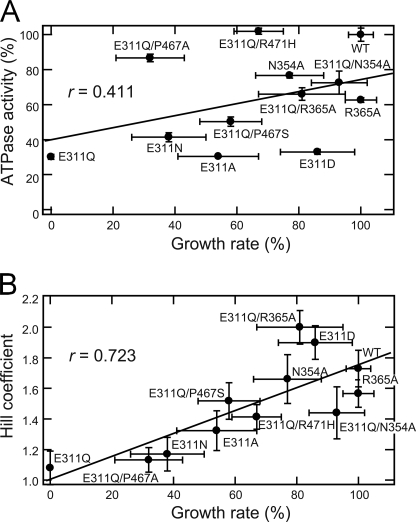

To further examine the relationship between the in vivo function and the ATPase property of p97, we compared the growth rate of yeast cells expressing various Cdc48p mutants and the ATPase activity of the corresponding mutants of CDC-48.1 (Fig. 5). The growth rate of the mutant cells was related poorly to the ATPase activity because mutants allowing fast growth do not always exhibit high ATPase activity. In contrast, the Hill coefficient was well related to the cell growth rate with the correlation coefficient of 0.723.

FIGURE 5.

Relationships between the yeast growth rate and Hill coefficient or ATPase activity. Yeast cells were grown in liquid SD medium at 37 °C, and the growth was monitored by measuring A600, and the growth rates were determined from log-phase growth. The growth rate of mutant cells was plotted against the ATPase activity (A) and the Hill coefficient (B) of the corresponding CDC-48.1 mutants. The correlation coefficient (r) was determined by fitting the data as a linear model.

Although the AAA domains of CDC-48.1 and Cdc48p share 94.7% homology and 79.0% identity, there is a possibility that biological features of ATPase activity of two proteins are significantly different. To rule out the possibility, we purified some Cdc48p mutants, measured the ATPase activity, and compared them with the growth rate of yeast cells (supplemental Fig. S2 and supplemental Table S1). The cell growth rate was again related to the Hill coefficient greater than the ATPase activity itself. These results suggest that the positive cooperativity of D2 is critical for essential function(s) of p97.

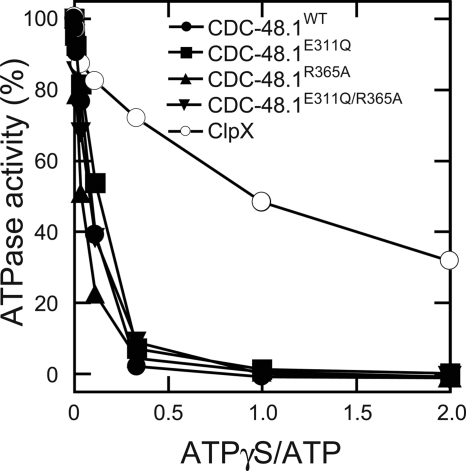

D2 ATPase Activity Is Coordinated between Subunits

To probe how CDC-48.1 communicates between subunits, we examined an inhibitory effect of ATPγS, which is a slowly hydrolysable ATP analog, on the ATPase activity of CDC-48.1 at 30 °C. If each protomer of the CDC-48.1 hexamer randomly hydrolyzes ATP, it is predicted that ATPase activity is decreased in inverse proportion to the percentile of ATPγS in total nucleotides. In accordance with this prediction, ATPase activity of ClpX, which is believed to hydrolyze ATP in a stochastic mechanism with positive cooperativity (23), decreased inversely to the concentration of ATPγS (Fig. 6) (24). In contrast, ATPase activity of CDC-48.1 was highly sensitive to the addition of ATPγS. In the presence of equal amount of ATPγS with ATP, CDC-48.1WT had barely detectable ATPase activity (Fig. 6). The ATPase activity of CDC-48.1E311Q, CDC-48.1R365A, and CDC-48.1E311Q/R365A was also highly sensitive to ATPγS (Fig. 6). These results imply that binding of ATPγS to only a few subunits in the hexamer stalls the D2 ATPase cycle, suggesting that the D2 ring adopts a different mechanism from a stochastic model like ClpX. Interestingly, the ATPase activity of CDC-48.1E311Q, which lost the positive cooperativity, also was significantly decreased by the addition of a small amount of ATPγS. Therefore, the coordination among protomers would still exist even if the positive cooperativity has been lost.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of ATPase activity by ATPγS. ATP hydrolysis by CDC-48.1 mutants and ClpX in the presence of indicated amounts of ATPγS with the constant concentration of ATP (3 mm) was measured at 30 °C by the malachite green assay. The ATPase activity of each protein in the absence of ATPγS was set to 100%.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized the ATPase activity and cooperativity of each AAA domain of p97.

ATP Binding to D1 Is Prerequisite for Intrinsic ATPase Activity of D2

Nucleotide-binding deficient mutants in D1 (CDC-48.1K257A) did not show detectable ATPase activity, but other mutants in D1 that allow ATP binding showed substantial ATPase activity (Fig. 2). Because D2 of CDC-48.1K257A binds to ATP as the wild type protein does (supplemental Fig. S1), ATP hydrolysis was impaired in the mutant, and therefore, ATP hydrolysis by D2 requires ATP binding to D1. Both consistent and inconsistent results have been reported using mammalian p97 (9, 15, 16, 18). Furthermore, our in vivo analysis has revealed that the corresponding yeast Cdc48p mutant must possess ATPase activity, at least enough to survive, although the mutation significantly affected the cell growth (19). This discrepancy is not due to the difference of species because recombinant yeast Cdc48p with the mutation, which had been expressed and purified in the same way, also showed quite low ATPase activity (supplemental Table S1). Rather, it is possible that some p97 adaptor proteins in vivo (or some contaminated effectors in the purified samples) help the nucleotide binding to D1 or accelerate the ATPase activity of D2 even if D1 is under the nucleotide-free conformation.

ATP-bound Conformation of D1 Perturbs D2 ATPase Activity

D1 of wild type mammalian p97 is found exclusively to bind with ADP in crystal structures (25, 26). Mutations in the D1 Walker B motif, which likely stalls in an ATP-bound state, resulted in significant decrease of the positive cooperativity of D2 as well as the ATPase activity itself (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Because mutations in the Sensor-1 and arginine finger residues of D1, which interact with γ-phosphate of the bound ATP in the ATP-binding pocket (Fig. 1B), suppressed the ATPase deficiency in the D1 Walker B mutant, it is likely that these interactions in D1 are the signal for the inhibition of the ATPase activity of D2. Briggs et al. (18) showed that both D1 and D2 rings can act independently in terms of nucleotide binding, and we also have found, by measuring the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, that D2 of CDC-48.1E311Q can bind to ATP as the wild type protein (supplemental Fig. S1), suggesting that D1 does not affect the nucleotide binding to D2. Taken together, D1 should be in the ADP-bound form for the normal D2 ATP hydrolysis cycle because the ATP-bound state of D1, which is sensed by the SRH residues, may perturb the communication between subunits of D2 during the ATPase cycle.

Positive Cooperativity Is Critical for Function(s) of p97 in Vivo

We found that the growth rate of yeast cells expressing a mutant Cdc48p varied. Most interestingly, the growth rate was well related to the Hill coefficient of the p97 mutant rather than the magnitude of ATPase activity itself (Fig. 5), suggesting that the positive cooperativity of D2 is critical for the in vivo function of p97. Why is the positive cooperativity of D2 important for the function of p97? Upon ATP hydrolysis, D2 undergoes large conformational changes, especially in a loop facing the pore of the D2 ring (25). Because this loop most likely interacts with substrate proteins (16), the conformational changes of D2 may lead to conformational changes of substrate proteins. One possibility is that the positively cooperative ATPase cycle may accelerate these conformational changes, thereby finishing the work in a short period to prevent a slip of the substrate back to the original state.

Possible Mechanisms Regulating Vital D2 ATPase Activity

In addition to the positive cooperativity, the ATPase cycle of D2 also is coordinated between the subunits, as evident from the fact that a small amount of ATPγS over ATP strongly inhibited D2 ATPase activity (Fig. 6). This behavior is apparently different from that of ClpX, which is believed to hydrolyze ATP in a stochastic mechanism. It was reported that ATP binding is limited to a subset of the D2 subunits (18, 27). Another group showed that at least two different conformations were observed upon binding of an ATP analog to D2 (28). These results exclude stochastic and concerted mechanisms of p97. Rather, it is likely that the D2 ring works in an ordered fashion such as a sequential or alternate mechanism.

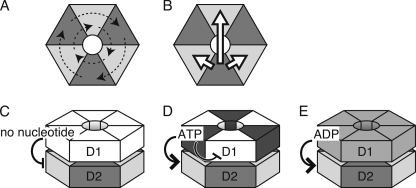

We also found that the noncooperative mutant still showed the coordinated ATPase activity (Fig. 6), indicating that mechanisms generating the positive cooperativity and the coordination should be different. Different mechanisms could be operated if the six protomers are divided into, at least, two groups. We propose a hypothesis that D2 of three protomers, which are not adjacent each other, in a group hydrolyze ATP in a coordinated manner but without cooperativity (Fig. 7A). This coordinated ATPase cycle by alternative protomers in a hexamer is possible because F1 ATPase adopts a similar mechanism (29). Positive cooperativity could be achieved by enhancing ATP hydrolysis of an adjacent protomers or the opposite one in a hexamer, which is in another coordinated group (Fig. 7B). Then, how does D1 influence these communications? Crystal structures of wild type p97 in the presence of various nucleotides showed all of the six D1 subunits were occupied with ADP (30), which allows the coordinated and cooperative ATPase cycle of D2 (Fig. 7E). Nucleotide-free conformation of D1 inhibited the ATPase cycle of D2, suggesting that nucleotide binding to D1 is prerequisite for the ATPase activity of D2 (Fig. 7C). If binding of ATP, but not ADP, to D1 of a protomer inhibits ATP-binding to D1 of the adjacent protomer, only D1 of alternate three protomers are in the nucleotide-bound state in the D1 Walker B mutant, thereby activating only one coordinated group of D2 (Fig. 7D). The SRH mutations may release this restricted binding of ATP and allow ATP binding to all six D1 domains, which leads to restoring the cooperative ATPase cycles. Heterogeneity in ATP binding to D1 may be the reason why no crystal structure with ATP-bound form of D1 has been elucidated. Further structural analyses of p97 in various nucleotide states and the direct observation of conformational changes during ATP hydrolysis will provide the information to elucidate the mechanism. And also, as it has been shown recently that matrix AAA protease in the mitochondrial inner membrane requires the coordinated ATPase cycle for its function (31), biological significance of the coordination of the p97 ATPase cycle for the functions will also be intriguing in the future.

FIGURE 7.

Proposed mechanisms of ATP hydrolysis by p97. See details in the text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Ichinose and Y. Kawata-Nishikori for secretarial assistance, S. Fukunaga and S. Ohtsu for technical assistance, and the members of the Ogura Lab for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology of Japan, and the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology program by the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Methods,” Table S1, and Figs. S1 and S2.

- AAA

- ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities

- SRH

- second region of homology

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-(3-thiotriphosphate).

REFERENCES

- 1. Ogura T., Wilkinson A. J. (2001) Genes Cells 6, 575–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ammelburg M., Frickey T., Lupas A. N. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 156, 2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Latterich M., Fröhlich K. U., Schekman R. (1995) Cell 82, 885–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rabouille C., Levine T. P., Peters J. M., Warren G. (1995) Cell 82, 905–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel S. K., Indig F. E., Olivieri N., Levine N. D., Latterich M. (1998) Cell 92, 611–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roy L., Bergeron J. J., Lavoie C., Hendriks R., Gushue J., Fazel A., Pelletier A., Morré D. J., Subramaniam V. N., Hong W., Paiement J. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2529–2542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braun S., Matuschewski K., Rape M., Thoms S., Jentsch S. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabinovich E., Kerem A., Fröhlich K. U., Diamant N., Bar-Nun S. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 626–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ye Y., Meyer H. H., Rapoport T. A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162, 71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarosch E., Taxis C., Volkwein C., Bordallo J., Finley D., Wolf D. H., Sommer T. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hetzer M., Meyer H. H., Walther T. C., Bilbao-Cortes D., Warren G., Mattaj I. W. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 1086–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Q., Song C., Li C. C. (2004) J. Struct. Biol. 146, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sasagawa Y., Yamanaka K., Nishikori S., Ogura T. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 358, 920–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishikori S., Yamanaka K., Sakurai T., Esaki M., Ogura T. (2008) Genes Cells 13, 827–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Song C., Wang Q., Li C. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3648–3655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeLaBarre B., Christianson J. C., Kopito R. R., Brunger A. T. (2006) Mol. Cell 22, 451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kobayashi T., Tanaka K., Inoue K., Kakizuka A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47358–47365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Briggs L. C., Baldwin G. S., Miyata N., Kondo H., Zhang X., Freemont P. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13745–13752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Esaki M., Ogura T. (2010) Biochem. Cell Biol. 88, 109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sugimoto S., Yamanaka K., Nishikori S., Miyagi A., Ando T., Ogura T. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6648–6657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan K. M., Delfert D., Junger K. D. (1986) Anal. Biochem. 157, 375–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang T. G., Suhan J., Hackney D. D. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 16502–16507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2005) Nature 437, 1115–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeLaBarre B., Brunger A. T. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 347, 437–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davies J. M., Tsuruta H., May A. P., Weis W. I. (2005) Structure 13, 183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zalk R., Shoshan-Barmatz V. (2003) Biochem. J. 374, 473–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davies J. M., Brunger A. T., Weis W. I. (2008) Structure 16, 715–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshida M., Muneyuki E., Hisabori T. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pye V. E., Dreveny I., Briggs L. C., Sands C., Beuron F., Zhang X., Freemont P. S. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 156, 12–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Augustin S., Gerdes F., Lee S., Tsai F. T., Langer T., Tatsuta T. (2009) Mol. Cell 35, 574–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.