Abstract

This original research is framed in phenomenological methodology, based on interviews conducted and interpreted using qualitative research methods. The findings suggest that, because of both direct and indirect factors (such as the nebulous nature of the work, general isolation in work conditions, and physical concerns), massage therapists perform their work with multiple sources of ambiguity that are potentially anxiety-causing. Licensing offers potential relief for this anxiety, but also generates a new set of frustrations and work concerns. The new concerns include the potential that practice will change to adapt to non-relevant standards and the difficulty of defining a body of work that frequently defies a “one size fits all” categorization. This pilot study suggests several areas for further exploration and also demonstrates the generativity of phenomenological methodology for research related to massage therapy.

Keywords: Bodyworker, professions, licensing, jurisdiction, anxiety, hermeneutic, qualitative, health care

INTRODUCTION

Symptoms of professionalization are emerging in the field of massage therapy(1,2). The present article documents original findings, situated in the context of the social psychology literature, about the impact of the movement toward professionalization on the work experience of massage therapists. Using qualitative methodology and phenomenological research methods, our study examined the lived experience of three massage therapists for emerging typifications related to the influence of licensing(3). The discussion invokes constructs from socio-historical views on professionalization and a psychodynamic perspective on work dynamics and identity.

The Changing Environment of Massage Therapy

Massage is an ancient tradition that, until recently, was more aligned with folk medicine and tradition than with science(4,5). Today, massage has gained increased acceptance in North America as an intervention to promote wellness and rehabilitation(6). In 2007, consumers spent an estimated $11.9 billion on visits to alternative care providers including massage therapists(7). Most professional massage is procured through self-payment(8), although its practice is increasingly being seen as an adjunct medical service. Simultaneously, massage therapists are coming to be viewed as service professionals with corresponding expectations and responsibilities(5).

Sociology has a long history of examining the process whereby occupations are restructured into professions. According to the literature, fiscal growth of a service can reshape its delivery channels, resulting in a synergistic relationship between its growth and a reorientation of its workers(9). In response to the changing environment, massage therapy is assuming structures, functions, and governance traits consistent with professional evolution(1,5). According to sociologic theory, professionalization is characterized by increased standards, formation of member-governed associations(10), licensure, and formalized codes of ethics(11). General traits that qualify “occupations” to rise to the status of “professions” involve complexities of definable knowledge, organization, education, and standardized codes of ethics(11,12). In addition, professions increasingly promote science as a source of occupational legitimacy and cultural principles(13). Consistent with professionalization, massage therapy is moving toward increasingly formalized standards and requirements(14), evidence-based practice(15,16), and regionally occurring disputes over jurisdiction(17).

Increased licensing is one manifestation of the professionalization dynamic apparent in massage therapy. In 1980, nine states regulated massage(18). At the time of writing, 42 states and the District of Columbia regulate the practice(18,19). Increased regulation accompanies tighter standards and other measures of professional conduct, and also less tangible features such as elevated social status for the practitioner. The effects of licensing have not been fully explored, especially at the level of individual practitioners and their massage craft. Although the therapeutic effects of massage are currently being measured, little research has considered the qualitative impact of the professionalization movement.

Walkley suggests that the professionalization and medicalization of massage will reframe the experience of the therapist(5). How practitioners view and experience their work is likely to evolve as related institutions and organizations exercise greater control over what was previously the artisan’s realm. Beyond influencing the logistics and techniques of service delivery, this control will likely affect how therapists conceptualize their work and “what they feel in their hands”(5). Hence, the move to professionalization carries inherent and possibly unforeseen implications for the practitioner and ultimately for the consumer.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This pilot study used a phenomenological(3) and hermeneutic research design(20). In qualitative research, hermeneutics is the theory and practice of interpreting the meaning of text as it is embedded in its culture, times, and social milieu(21). Phenomenology strives to capture lived experience through research strategies that look for the essence of the object or interaction(22). The researcher’s primary role is to collect and integrate data from multiple sources into an analytical format that reveals the inter-subjective meaning for the participants(22). Phenomenological research is most appropriate in circumstances new to empirical inquiry or when prevailing conditions are changing(21).

In keeping with phenomenological theory, research results are not necessarily representative of or able to be generalized to the entire population of massage therapists. Our pilot study is intended to inform subsequent phenomenological studies and quantitative and survey research. Phenomenological significance is expressed in relevance through typifications (as distinct from the reliability factors of quantitative results). Typifications are correlations in experience identified across all participants in a particular study; they generally require verification through further study of the phenomenon. Typifications are also shaped by the researcher’s knowledge and awareness, which are considered to be an integral part of the analysis(3). In the present study, the primary researcher is also a practicing massage therapist.

The primary researcher, LDF, conducted the study and the analysis. The secondary investigator, EG, is a Reiki practitioner who has conducted empirical research in alternative and complementary therapies; she is also a phenomenological research investigator. EG assisted in framing the written study to CONSORT and the accepted standards of the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. In future investigations involving multiple analysts, steps should be taken to identify and resolve variances between the analysts. In this pilot study, perceptual variances were not a factor because of the division of tasks.

Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited by e-mail message and telephone in a large US urban area in which massage therapists are required to be licensed. To meet the selection criteria, practitioners had to be practicing massage therapy currently or had to have practiced within the preceding 6 months. Practitioners that did not possess a license qualified to be Participant 1. Practitioners that lacked advanced credentials or specialty licenses were offered the position of Participant 2. Practitioners that had advanced credentials in addition to a license were offered the position of Participant 3. These licensure criteria were intended to allow for an exploration of variances related to the relatively new authority of licensure.

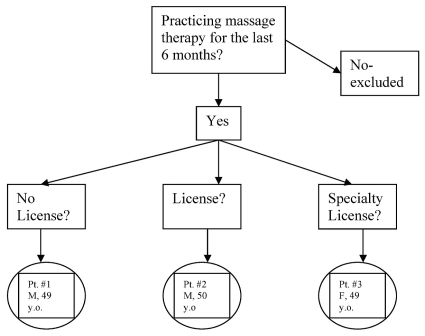

Practitioners were excluded if they had not been actively practicing during the preceding 6 months, did not meet the study criteria (Figure 1), or could not commit time within the necessary schedule. Each participant in the study is identified by an alias of their choosing. The Institutional Review Board at Fielding Graduate University approved this research project, and all participants gave written informed consent for the study. Participants received no monetary compensation for their participation in the study.

Figure 1.

Participant (Pt) selection flowchart. M = male; y.o. = years old; F = female.

The participants enrolled in the study were 3 massage therapists in active practice in a large urban metropolitan area. Two were men (49 and 50 years of age), and one was a woman (40 years of age). One man began practicing in 1986; the other, in 1992. The woman began practice in 1999. The woman carried licenses from multiple bordering jurisdictions and also had advanced training credentials. One man was licensed, but had no advanced training credentials or certifications. The other man did not qualify for licensure and was practicing without a license.

Interviews

Consistent with phenomenological research methods(22), data were collected during interviews. Each participant was interviewed twice. The first interview was structured into two parts: the first collected the background and work experience of the therapists; the second explored their thoughts about how licensing had affected their practice. The initial interview was conducted in person, took 60 – 90 minutes, and was audiotaped and transcribed. Hardcopy and e-mail messages were used to collect corrections and revisions from the participants, and changes were made as instructed. A subsequent conversation asked the participants to comment on the initial interview and to offer any interpretive thoughts. These second interviews were conducted by telephone or exchange of e-mail messages, and each one took 10 – 20 minutes (Figure 1).

Analysis

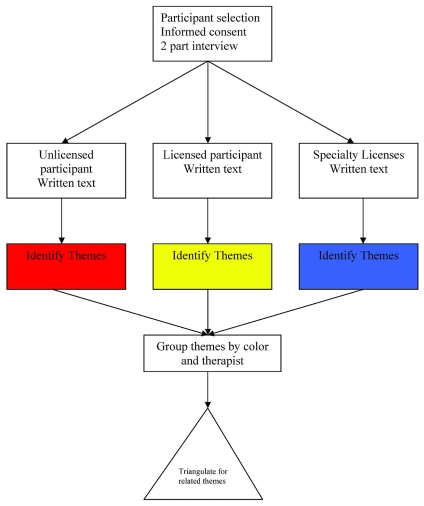

Interview text was analyzed and categorized using phenomenological methodology(20). In listening to and reading the text several times, LDF highlighted phrases that seemed essential or revealing about the phenomenon and then created a visual board to display words or phrases that captured the essence of the text. These words and phrases were moved around the board and grouped by similar characteristics. Identified patterns were categorized into emerging themes (typifications). LDF then copied representative quotes from each interview into another document and grouped those quotes by typification. At each step, LDF used color-coding to identify the source by level of credentialing (a technique to track whether the variation in credentials was associated with different emerging typifications—Figure 2). The analysis invoked a hermeneutic approach to interpret the data within the theoretical constructs related to professionalization and psychodynamics(21).

Figure 2.

Study flow chart.

In this study (consistent with established phenomenological, hermeneutic research methods), reliability is achieved through consistency(23). In qualitative field research, the analyst represents a variable because of the inherent subjectivity of the data. As the single researcher, LDF executed the data collection and analysis in a completely transparent framework, contributing to internal consistency. Validity in the study was achieved through recognized strategies established for qualitative research design(24): member-checking (taking the final report of specific themes back to the participants to obtain their thoughts about the accuracy of the representations of their comments) and use of an external auditor (a published expert in the area of applied psychodynamic theory(25)). This strategy provided further external consistency by triangulating the themes emerging from the data against applied and theoretical constructs(23).

RESULTS

According to psychodynamic theory, anxiety is a predictable byproduct of tensions in the workplace. Entrenched in early childhood experiences and the developmental internalization of authority attitudes, anxiety issues continue to trigger unconscious psychological reactions in the adult(26,27). Hence, identifying particular anxiety threads provides a better understanding of the forces interacting with professionalization on a personal level.

Several anxiety-related themes emerged from the work of the participating massage therapists. The ambiguity and nebulousness of massage therapy, while affording creativity and deep rewards, contribute to a climate of uncertainty. Because the experience is structured to be intensely private, the value or effectiveness of the therapist’s work goes unmonitored and unevaluated. Except for the feedback of the very people they are touching, the therapists have few touchstones available to gauge task-related excellence. In addition, all participants described a wordlessness about the work: not only are sessions usually quiet, they lack a coherent language to describe what happens. To further contribute to anxiety potential, the work is often performed in isolation, with the secluded, lone settings resulting in isolation for the therapist. Tensions over unclear boundaries, and past and continuing associations with prostitution add real and perceived threats. Participants who had satisfied minimum credentials found licensing to be a source of comfort and support.

Task-Related Anxiety Threads

Nebulous Nature of Massage Therapy

Several threads of uncertainty emerged from the data:

Unclear definitions about what massage consists of

Vagueness related to the parameters of excellence

Lack of language to name the work

The components of massage are highly variable and often prescribed by a particular school(5,7). Despite recent efforts toward evidence-based practice, most massage routines, protocols, and techniques are not reinforced by science, but are grounded in folk wisdom and intuition(15). Most therapists work independently(28). Even if monitoring is occurring, the parameters of excellence for any particular therapist are highly qualitative, subjective, and even wordless(5). Those in the field often talk about “quality of touch,” a commonly held opinion being that it is an innate talent that defies cultivation through training(5). The ambiguous nature of the work and the setting surfaced in several areas of the text, including this statement:

I know it’s good, and I know that it makes sense, and I know it’s got depth, and it’s hard to put words to it.... When I was teaching, that was one of my biggest struggles with students, was articulating what it was I was feeling.

— Billy Bass; July 26, 2009; lines 708–720

Isolation in the Work and Work Setting

The data reflected that, even in a group practice, the actual work is isolated and lacks a well-developed language. All three of the participants expressed a preference for performing massage without talking with the client. For example:

I don’t like to talk; it’s my preference during the session. I’ll intentionally breath certain ways, and you know, the recipient’s body just picks right up on that, I don’t have to say anything

— Joseph; June 29, 2009; line 298

We’re not going to talk today. I just ... the stuff I’m feeling, I just want to pay attention here.

— Billy Bass; July 26, 2009; line 611

I think we don’t talk enough about our work. We work in a vacuum.

— Billy Bass; July 26, 2009; lines 784–786

Silence does not necessarily translate into isolation. However, the quietness of the sessions, the dependence on nonverbal communication, and the solitude of the work’s execution combine to contribute to a sense of isolation. Unlike other somatic practices or performance-based vocations such as sports or dance, the work of a massage therapist lacks a viewing audience. The touch-linked intimacy and expectations related to wellness with quasi-medical responsibilities contribute to underlying performance insecurities:

Maybe I’m just projecting my old insecurity ... but I think that a lot of the reason we work in a vacuum is that we’re afraid that somebody’s going to think that we don’t know what we’re doing.

— Billy Bass; July 26, 2009; lines 788–792

The data also indicated that licensing, accompanied by other characteristics of professionalization, can help to alleviate the anxieties related to the ambiguous nature of the work, as demonstrated in this statement:

I think that it really lets people know that we’re for real. And we’ve done this training, and we have standards.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 800–803

Threatening Aspects of Massage Therapy

Massage therapists face real and perceived threats. The link between massage and prostitution has been in existence for centuries(5). For women, who account for more than 80% of massage therapists, the real and perceived threat of insult and possible attack is a predictable source of anxiety(2,28,29). Male therapists are also reportedly vulnerable (P3; July 2, 2009; lines 749–751). Referring to work in spas, our female participant described particular situations in which she felt threatened (P3; July 2, 2009; lines 696–697):

He had already been asking, hinting ... at not wanting the sheet, and working his inner thigh.... I don’t think he was that happy that I was only working his outer thigh when he was face up. And I ended up ending the session early because ... I realized that I was getting so uncomfortable. And so I said to him, “I’m so sorry. We’re going to have end early. You’ll be charged less. They booked this without enough time.”

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 708–727

Licensing creates a barrier against the danger from threats of sexual harassment and confusion with prostitution. In one situation, our female participant described relying on licensing-related standards:

What I blurted out was “No, it’s the law. You have to have a sheet on, you have to be covered. I will undrape you as I work, parts that I’m working on.” I just blurted that out, and I thought it was the law, but I wasn’t for certain. I mean I figured you had to be covered by something.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 560–567

Anxiety Reduction Through Professionalization

Licensure can serve to reduce anxiety related to the work of massage therapy by increasing credibility:

When I first did the licensing, and the NCTMB application, going through that process was just good in terms of realizing this is a serious job.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 804–806

Licensing also provides substantive support, as demonstrated in these statements:

When a client ... wants to know about my credentials, [then I say,] “Let me tell you what I have.”

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 784–785

I think it’s really given me support and guidance, probably many times. Again, I feel real lucky that when I started, the licensing had just begun. I think it would have been harder to get started.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 823–828

Professional status also confers social status and various conditions that make the work more pleasant and more therapeutic(10). Our female participant described a social situation in which she relied on her status as a licensed professional:

I think it helps, I would say, in work and in social situations.... I remember one person saying, “Oh that’s so great you’re a massage therapist.” She said, “You must get a lot of dates.” ... I think my jaw dropped, and I was sort of mad, because I realized that she didn’t get it. She didn’t get that A) you’re not allowed to date your clients unless you cut it off for at least six months ...; B) that it would be real awkward anyway; and C) that I would use the work to get dates! ... So, it’s very helpful, I can say, “Oh no, I’m licensed.” And I think I said to her, “No, no, we don’t date clients. That really helps keep it a very therapeutic session and makes it beneficial to the client and the therapist.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 533–547

Anxiety Related to Licensing

Licensing establishes an external authority as a voice in the work and addresses the workers’ need for stability and status. But this outside authority can be another source of anxiety, because the independent massage therapist (p. 30–31)(5) is forced to conform to regulatory requirements(30). The underlying professionalization movement, linking tensions between individuality and group conformity, is both revered and resented(5,30):

This has all been put in place for a reason ... you know, getting a notary and all this other stuff is such a pain. But, it gives us credibility.

— P3; July 2, 2009; lines 804–810

According to psychodynamic theory, workers display reactions associated with inherent authority issues(27). The power of licensure as an authority was referenced by the unlicensed participant:

With all these battles with licensure ... I just want to use my skill, I can’t even get a job ... there’s no job security.... I don’t have disability insurance.... So, that’s where the anxiety comes from... I could actually lose this.

— Joseph; June 29, 2009; lines 837–849

Applied Quality in Licensing and Training

As Joseph points out in his interview, current requirements for national examination and licensing do not directly contain an applied component. The basic training requisite to sit for the exam is intended to cultivate applied skills competence. But of the estimated 1500 massage therapy programs in the United States, most are now approved by generic certifying agencies with limited massage therapy–specific pedagogy requirements(31). As a result,

[there are] a lot of things not being taught that should be taught.

— Joseph; June 29, 2009; lines 244–245

To increase professional standards of practice ... I’d like to see a hands-on [exam].... If you are going to become a massage therapist ... you got to spend at least 15 or 20 minutes working on ... designated people that want to see what the quality of your touch is.

— Joseph; June 29, 2009; lines 499–505

DISCUSSION

Licensure can serve to reduce anxiety in several ways:

It is attached to standards that convey work integrity, and it adds clarity to an inherently obscure work process.

It also provides a right to work and protects occupational jurisdiction.

It elevates social status and confers legitimacy, and separates massage therapy from prostitution and reduces threat of sexual harassment.

The effects of licensing can be differentiated into “entry level” and “ongoing oversight.” This distinction guided how the themes emerged from the data. Specific inquiry into the basis of this distinction was beyond the scope of this pilot study, but could prove to be a valuable project for the future. Licensing—and conditions related to professionalization—also create new anxieties, not only for the unsanctioned. The spiral toward higher professional standards demands greater consistency and uniformity of practice. The work itself could be changed, with the associated anxiety of who has a voice in that change. Being judged by rapidly changing knowledge and new constructs makes the therapist susceptible to potential failure in a system in which the rules are changing—an additional source of anxiety.

The data also indicated one emerging gap: effective monitoring of the therapist’s qualitative skills beyond the number of hours trained. Other themes that arose included the complications from being self-employed, inconsistent training, confused social status, cultural norms about touch, and workplace isolation. Some of the individual anxieties expressed by the study participants speaks to an underlying inconsistency in definitions, characteristics, and even expectations about the nature of the work. As is typical of manual therapies, virtuosity in tactile experience is innate and also takes years to develop(5). Rather than ignore this critical aspect of the essence of massage, its elusiveness in language calls for a holistic appreciation. The praxis of massage could describe a new approach to credentialing based on a theoretical–practitioner model. According to Walkley, a new category of manual practitioner, with a different range of techniques and education, will emerge in the United States(5).

Still, the empowerment resulting from professionalization projects can influence context. Although professionalization alone does not directly mitigate the challenges of anxiety and the lack of definitions, it could have a long-term impact on how massage therapy is delivered(12). Integration into the health care delivery system is an increasing possibility “because people look at massage therapists these days ... as health care practitioners” (Billy Bass; June 26, 2009; lines 231–232)(5). At a time when the entire system is subject to reordering, the evolution of massage therapy can work synergistically to affect the delivery of wellness services, as evidenced by the literature.

Finally, the lack of clarity concerning what constitutes massage therapy points to an integrity issue. Although various components of the craft currently defy categorization, the practice balances on the cusp of change. Better definition of the synergistic properties of massage today is a logical first step in designing and promoting a vision of what massage therapy should become. This area is clearly calling out for further investigation, including variations based on regional practices and training factors.

The therapists interviewed consistently conveyed deep passion and reverence for their work. If the collective body of massage therapy can manage to incorporate the depth and wisdom arising from its roots into the vision of its future, the energy driving the move to professionalization could be enhanced by increased personal investment from the community:

I feel like I’m blessed, ’cause I’ve had a vocation. It’s not just a job. In fact, I would go so far as calling it a spiritual calling. But it’s taken me a while to get to the place where I can say, “Yeah, this is a calling” ’cause I think a lot of things have to come together ... going beyond ... the mechanical aspect of giving a massage

— Joseph; June 29, 2009; lines 279–286

The study’s results indicate that licensing is a factor in the work experience of each of the participants. The effects of licensing carry over to multiple aspects of the work experience, especially for the unlicensed participant. This pilot study suggests several areas for further exploration, including consideration of regional, training, and demographic factors. The study also demonstrates the potential generativity of phenomenological methodology for massage therapy–related research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks go to Dr. Larry Hirschhorn, Dr. Katrina Rogers, Dr. Valerie Bentz, Dr. David Rehorick, and Dorianne Cotter-Lockard, and to the study participants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kahn J. Massage Therapy Research Agenda. Evanston, IL: Massage Therapy Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Massage Therapy Association (AMTA). AMTA Timeline – Full Version: Advancing the Massage Therapy Profession for 60+ Years. AMTA website. http://www.amtamassage.org/About-AMTA/AMTA-History.html. Published n.d. Updated n.d. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- 3.Bentz VM, Rehorick DA. Transformative phenomenology: a scholarly scaffold for practitioners. In: Rehorick DA, Bentz VM, eds. Transformative Phenomenology: Changing Ourselves, Lifeworlds, and Professional Practice. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2008: 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich GJ, ed. Massage Therapy: The Evidence for Practice. Edinburgh, UK: Mosby; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walkley S. When the body leads the mind: perspectives on massage therapy in the United States. In: Oths KS, Hinojosa SZ, eds. Healing by Hand: Manual Medicine and Bonesetting in Global Perspective. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press: 2004: 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg DM, Cohen MH, Hrbek A, Grayzel J, Van Rompay M, Cooper R. Credentialing complementary and alternative medical providers. Ann Intern Med. 2002;13712:965–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;(18):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field T. Touch. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macdonald KM. The Sociology of Professions. London, UK: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson JA. Professions and Professionalization. London, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbott A. The Systems of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatch NO, ed. The Professions in American History. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimball B. “True Professional Ideal” in America: A History. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondurant C. Why massage therapy guidelines? Massage Today 2008;810:1–3, 11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn J. Introduction. In: Rich GJ, ed. Massage Therapy: The Evidence for Practice. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2002: xi–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hymel GM. Advancing massage therapy research competencies: dimensions for thought and action. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2003;73:194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene E. Maryland massage therapy bill passes after 10 years. J Altern Complement Med. 1997;31:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Massage Therapy Association (AMTA). Michigan Governor Signs Massage Therapy Licensing Act. AMTA website. http://www.amtamassage.org/articles/2/PressRelease/detail/2138. Published January 9, 2009. Accessed March 2, 2009.

- 19.Crownfield PW, Beychok T, Bondurant C. Winds of change in North Carolina and Pennsylvania. Massage Today. 2008;812:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bentz VM, Shapiro JJ. Mindful Inquiry in Social Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hymel GM. Research Methods for Massage and Holistic Therapies. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuman WL. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. New York, NY: Allyn and Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirschhorn L, Barnett CK, eds. The Psychodynamics of Organizations. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschhorn L. The Workplace Within: The Psychodynamics of Organizational Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirschhorn L, Gilmore TN. The psychodynamics of a cultural change: learnings from a factory. In: Hirschhorn L, Barnett CK, eds. The Psychodynamics of Organizations. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993: 119–142. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Associated Bodywork and Massage Professionals (ABMP). Massage Profession Metrics: Practitioner Characteristics and Professional Membership Patterns. ABMP website. http://www.massagetherapy.com/media/metricscharacteristics.php. Published n.d. Updated n.d. Accessed January 8, 2010.

- 29.Stokes J. The unconscious at work in groups and teams: contributions from the work of Wilfred Bion. In: Obholzer A, Roberts V, eds. The Unconscious at Work. London, UK: Routledge; 1994; 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aronson E. The Social Animal. 4th ed. New York, NY: WH Freeman and Company; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Backgrounder—Massage Therapy: An Introduction. Training, Licensing, and Certification. NCCAM website. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/massage/#certs. Published September 2006. Updated June 2009. Accessed January 8, 2010.