Abstract

Background

Healthy, full-term, exclusively breastfed infants are expected to lose weight in the first days following birth. There are conflicting opinions about what constitutes a normal neonatal weight loss, and about when interventions such as supplemental feedings should be considered.

Objective

To establish the reference weight loss for the first 2 weeks following birth by conducting a systematic review of studies reporting birth weights of exclusively breastfed neonates.

Methods

We searched 5 electronic databases from June 2006 to June 2007: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; MEDLINE (from 1950); CINAHL (from 1982); EMBASE (from 1980); and Ovid HealthSTAR (from 1999). We included primary research studies with weight loss data for healthy, full-term, exclusively breastfed neonates in the first 2 weeks following birth.

Results

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. Definitions, types of measurements, and reporting styles varied among studies. In most studies, daily weights were not measured and measurements did not continue for 2 weeks. Mean weight loss ranged from 5.7% to 6.6%, with standard deviations around 2%. Median percentage weight loss ranged from 3.2 to 8.3, with the majority around 6%. The majority of infants in these 11 studies regained their birth weight within the first 2 weeks postpartum. The second and third days following birth appear to be the days of maximum weight loss.

Discussion

Methods used to report weight loss were inconsistent, using either an average of single lowest weights or a combination of weight losses. The 7% maximum allowable weight loss recommended in 4 clinical practice guidelines appears to be based on mean weight loss and does not account for standard deviation. Further research is needed to understand the causes of neonatal weight loss and its implications for morbidity and mortality.

Infant weight measurement is one of the tools most frequently used to assess breastfeeding adequacy. Neonates receive only small amounts of fluids in the first days following birth,1 and they tend to lose weight before they begin to gain weight.2 Excessive weight loss or inadequate weight gain can be indications of low milk production or of insufficient milk transfer. To ensure adequate intake and, at the same time, to avoid inappropriate supplementation, parents and professionals need evidence to assess patterns of neonatal weight change and to make decisions about infant feeding.

Expert opinions and guidelines disagree about what constitutes a normal neonatal weight loss. How much weight loss should be considered a red flag? What is the upper limit that indicates intervention is required? We did a systematic review to answer the question, “What is a normal physiological weight loss for full-term exclusively breastfed infants in the first 2 weeks following birth?”

We made 3 assumptions. First, neonatal weight loss in the first days following birth is expected, and we therefore refer to such weight loss as physiological weight loss. Second, to define abnormal or pathological weight loss, we need evidence of what would be considered a normal or reference weight loss. Third, we expected to find observational studies (e.g., cohort, case-control) rather than randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in our search. The nature of the research question and the implications of the answer for the care of breastfed infants require a rigorous methodology. Therefore, we chose to complete a systematic review even though we sought evidence for parameters of weight loss and not for optimal interventions.

Methods

Search methods

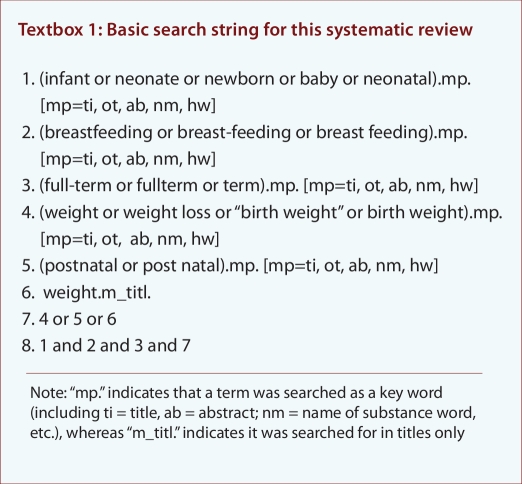

Two of us (JNW, GC) completed separate database searches through our respective university libraries. We searched 5 electronic databases from June 2006 to June 2007: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, MEDLINE (from 1950); CINAHL (from 1982); EMBASE (from 1980); and Ovid HealthSTAR (from 1999). Boolean searches using alternative spellings of key words were run multiple times (see Textbox 1). Boolean searches were also completed using Google and Scirus search engines. We identified relevant clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and used their reference lists to ensure a thorough search. We did not restrict our search by dates, study design (all research methods were considered), language, or country of origin.

Textbox 1.

Basic search string for this systematic review

Inclusion criteria

We included only primary research studies that reported data about weight loss occurring in the first 2 weeks following birth. We defined primary research as research undertaken by the authors, and we included systematic reviews and secondary analyses of data sets. The "primary research" criterion allowed for the inclusion of research studies that collected data about weight loss as part of their protocol, even if their research was not intended to be about weight change patterns. We excluded cited research, narrative reviews, and reports that did not measure and report individual weight loss.

We included studies of healthy, full-term, singleton, breastfed babies. We defined full-term as a gestation of more than 259 days (36 6/7 weeks),3 and we defined breastfeeding (i.e., exclusively breastfed) as fed only breast milk, whether at breast or by bottle, with no other food or liquids, including water, with the exception of medicines, vitamins or minerals.4 We excluded studies of infants fed or supplemented with formula, and preterm, near-term, or multiples (e.g., twins, triplets), unless data for full-term, singleton, exclusively breastfed infants were reported separately.

Data abstraction and analysis

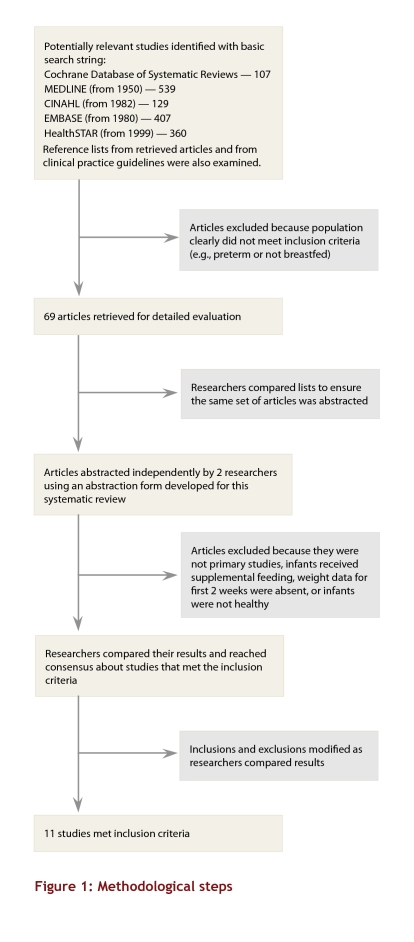

We conducted separate searches and abstractions. First, articles were screened and retrieved based on their titles and abstracts (see Fig. 1 for methodological steps). In the next step, 2 of us (JNW, GC) used an abstraction form developed for this systematic review to analyze screened studies to determine eligibility for inclusion. Results were compared to reach a consensus. Six authors were contacted for clarification.5-10

Figure 1.

Methodological steps

We constructed tables and examined key aspects of each study: research design, population size, types and timing of data collection, methods for measurement, definitions of breastfeeding, and elements of reporting. We used descriptive statistics from the studies. In one case, to answer the research question, we had to re-analyze data in order to pool the study subjects to obtain an average for the whole group.11

Results

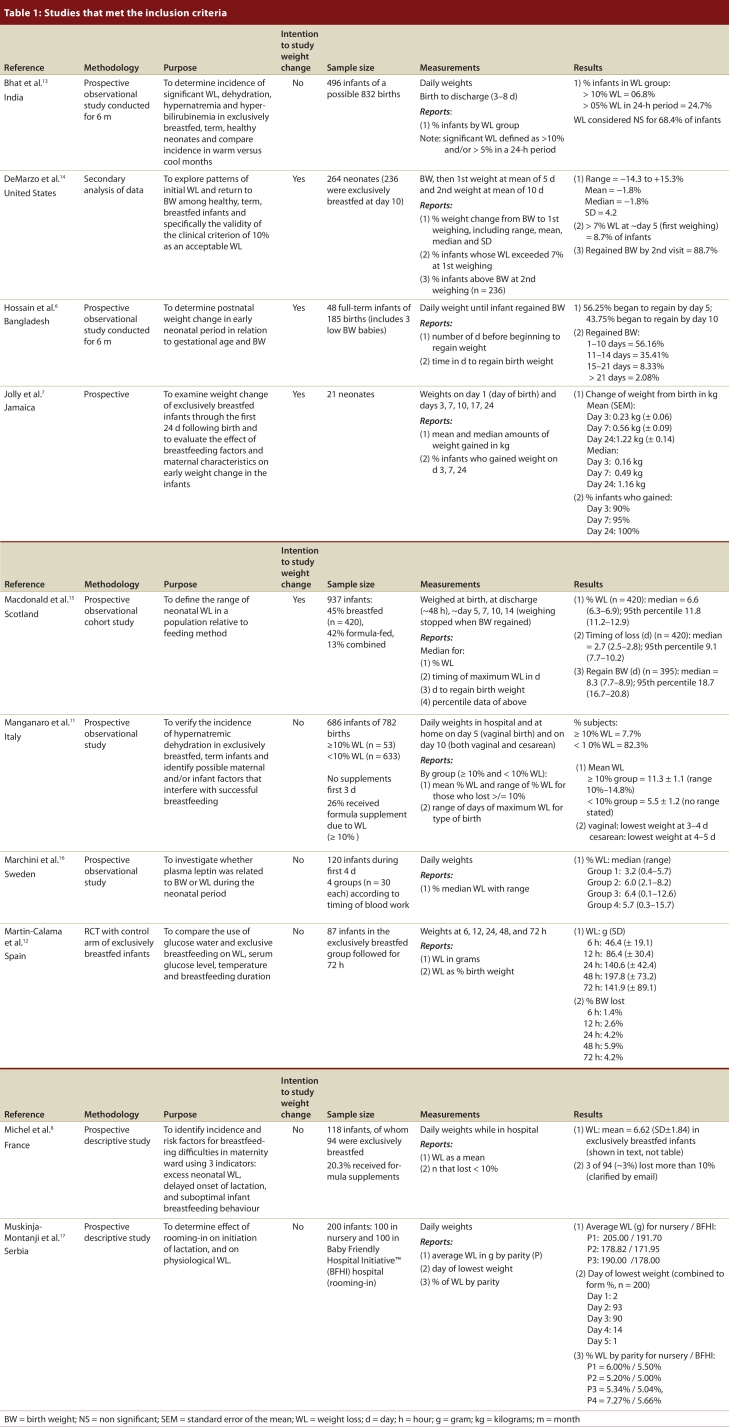

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria (see Table 1).6-8, 11-18 Ten of the studies were observational. One study, an RCT,12 provided data from the control arm that we used. With one exception, all were prospective studies in which data were collected on the basis of a research question. The one exception was a secondary analysis of data.14 Six of the 11 studies researched non-weight topics but provided data about weight change patterns. Nine of the studies were reported in English, one in French, and one in Croatian. Studies were conducted in Bangladesh, France, India, Italy, Jamaica, Scotland, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, and the United States.

Table 1.

Studies that met the inclusion criteria

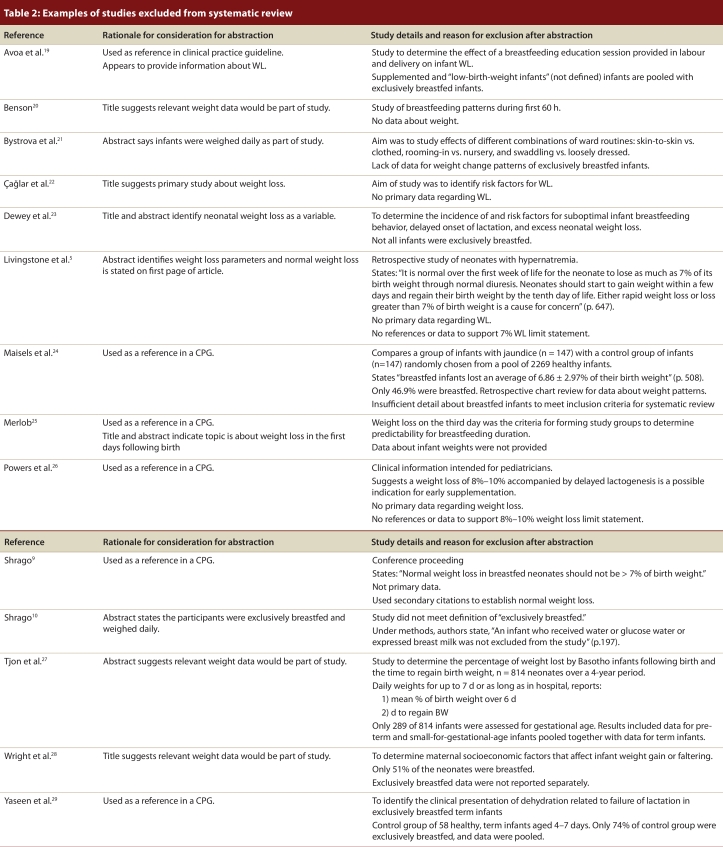

Authors of the included studies reported the amount and timing of weight loss using a variety of descriptive statistics (see Table 1, under Study Results). None of the studies provided morbidity or mortality statistics. Examples of excluded studies and rationales for their exclusion are provided (see Table 2).5,9,10,19-29

Table 2.

Examples of studies excluded from systematic review

Appraisal of included studies

The studies included in this review represented several different cultures. In all studies, measurements started from birth. The populations were comparable in age, but the length of time for and frequency of weight measurements were not comparable across studies. Sample sizes varied from 21 to 937, with a median of 120. All but one study had more than 40 subjects. Most studies had convenience, not random, samples.

Measurement bias occurred in many of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. The frequency of weighings was inadequate. Most of the studies weighed the infants daily while they were in hospital, but not after discharge. The lack of measurements makes determining lowest weight and normal patterns of weight loss impossible. The fact that most of the research studies were not primarily intended to study weight explains some of the variations. In one study, researchers completed a secondary analysis of data and reported maximum weight loss, even though infants were weighed only twice over a 2-week period.14 With only 2 weights measured in 2 weeks, it is not possible to determine the lowest weight, or when it was reached.

Definitions for breastfeeding and weight loss, as well as inconsistencies in approaches and reporting methods for descriptive statistics, were problematic. Most studies did not specify a definition of breastfeeding. In 1 case, the term “exclusively breastfed” was used, but later in the report we found that infants who received water or glucose water were included.10 Neonates frequently had substantial weight loss, in which case supplementation might be expected, but researchers rarely identified when the infants received supplemental feeding. Without a clear definition of breastfeeding, and without clear reporting of supplementation, it is difficult to discern supplemented from exclusively breastfed neonates (i.e., nothing by mouth except breast milk and, possibly, medicines or vitamins). We contacted authors to establish the definition of breastfed infants in their studies, and we only included study data that met our definition.

Definitions of weight loss varied. Maximum weight loss for an infant could be the lowest single weight or it could be an average of the daily losses. Furthermore, a mean loss for the study group could be each infant’s one lowest weight, pooled and averaged, or all of the infants’ weight losses averaged for the group. The size of the sample often varied within a study (i.e., smaller sample on day 3 than on day 1) due to attrition and this fact complicates calculations of mean weight loss.

There are some inconsistencies as to whether the day of birth was counted as day 0 or day 1, a detail that may cause confusion with regard to expectations as to when infants should begin to gain weight. Health status and the infants' status as singletons or multiples were often not clear; we contacted authors for clarification on these points when necessary. If the subjects were referred to as dyads (i.e., mother and infant) we presumed the neonates to be singletons; we assumed infants to be healthy if they were discharged to home.

Among the 11 studies included in this review, 1 study stands out. The study by MacDonald et al.15 followed infants for 14 days. The infants were weighed daily while in hospital but intermittently after discharge. The researchers took this factor into account by reporting changes as medians. Based on the results of this study, it appears that weight loss of up to 12% of birth weight is experienced by about 95% of neonates.15 Within a range, the first day to begin regaining weight is around day 4, and infants regain their birth weight around day nine.15 Although the longer follow-up period of this study is a strength, the lack of daily weights weakens the findings.

Amount of weight change

Weight loss patterns were described in terms of amount and timing, and the wide range of data descriptions made it difficult to compare or combine study results. In 10 of the 11 included studies, weight change was measured as amounts of weight; the 11th study reported weight patterns based solely on the timing of changes.6 In the 10 studies that reported the amounts of weight change, 8 types of descriptive statistics are used to express the amount of weight change: (1) mean weight loss;8,11,12,18 (2) median weight loss;8,15,16 (3) range of weight change;11,14,16 (4) number of subjects over or under a percentage lost;11, 13,14 (5) amount in grams or kilograms lost or gained;7,12,18 (6) percentile data;15 (7) mean change;14 and (8) weight change by parity or birth type.17

Mean weight loss ranged in the studies from 5.7% to 6.6%, with standard deviations hovering around 2% (see Table 1).8,11,18 Whether mean percentage represented the average of maximum daily weight loss measurements (i.e., 1 measurement per neonate) or an average of all weights taken is not clear. Manganaro et al.11 divided their subjects into 2 groups (< 10% and ≥ 10%); pooling the results, we determined that the average for the group as a whole was 5.9%. Median percentage weight loss ranged from 3.2% to 8.3%, with the majority of reported medians around 6%.8,15,16

The authors who reported the range of weight change had collected data for 72 hours to 24 days, and the range in these studies varied from a loss of 14.3% to a gain of 15.3%.24,26,28 Authors of 3 papers grouped subjects according to the percentage of weight change. For example, DeMarzo et al.14 report that 8.7% of infants lost more than 7% of their birth weight, whereas Bhat et al.13 found 6.8% lost more than 10% of birth weight, and Manganaro et al.11 found 7.7% lost more than 10% of birth weight. The choice of 7% or 10% for grouping the sample appears to be an arbitrary demarcation for substantial weight loss.

Jolly et al.,7 Martin-Calama et al.,12 and Muskinja-Montanji et al.17 report the number of kilograms or grams neonates lost or gained. Martin-Calama et al.,12 describe mean weight losses that peaked at 48 hours, after which mean gains begin. Muskinja-Montanji et al.17 report weight loss in grams by parity; and the days that most infants lost weight were day 2 and 3. Contrary to the other studies showing weight loss in the first 2 days, Jolly et al.7 report substantial weight gains, with 90% of the study infants averaging a gain of 230 grams by the third day.

Three authors were unique in their reporting of weight changes. DeMarzo et al.14 report the mean change between 2 weights (around day 5 and day 10) measured at post-discharge clinical visits. MacDonald et al.15 demonstrate the upper limit of weight loss in their study, by stating that the 95th percentile is 11.8%. Rodriguez et al.,18 in their study of body composition, report average weights for 3 days, but do not provide data about the change.

Timing of weight change

Some of the researchers looked at the day on which the lowest weight (i.e., the nadir) was reached and the day on which neonates regained their birth weight. Five approaches were used to describe the timing of weight change: (1) the day the infants regained their birth weight;6,15 (2) the percentage of infants who gained or lost on a particular day;13,14 (3) the day of lowest weight;17 (4) weight change by parity or birth type;17 and (5) median for both number of days losing weight and days to regain birth weight.15

In the studies that report the amount of time it took for infants to regain their birth weight, the majority of infants regained their birth weight within the first 2 weeks. Hossain et al.6 found 91.57% had regained initial weight by day 14, and DeMarzo et al.14 state that 88.7% infants were back to birth weight by the second clinic visit (average day 10).

The day of lowest weight is reported by Michel et al.8 as day 1 and 2, and by Muskinja-Montanji et al.17 as day 2 and 3. In each study, the 2 combined days account for about 90% of the sample. The discrepancy seems to be a matter of counting the day of birth as day 0 or day 1 and then the second 24 hours as day 1 or day 2.

Hossain et al.6 and Jolly et al.7 identify the day infants began to gain weight, with very different results: 56.25% by day 5 and 90% on day 3, respectively. This discrepancy is an outstanding feature; with only 2 studies describing weight change in this manner, it is difficult to determine which is the outlier.

Two authors have unique methods of reporting. MacDonald et al.15 report the median number of days of weight loss and the median day to regain birth weight as 2.7 and 8.3 respectively. Manganaro et al.11 note that infants in their study who were born vaginally reached their lowest weight between day 3 and 4, and infants delivered by cesarean section reached their lowest weight between day 4 and 5.

Review of clinical practice guidelines

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are defined as “systematically developed statements [based on best available evidence] to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”30 Four key CPGs, among others, were found during searches for this systematic review.31-34 Three of the guidelines31-33 are about overall breastfeeding, and 1 deals specifically with supplementation.34

These CPGs on breastfeeding advise against supplementation (i.e., replacement breastfeeds) as a standard or casual practice, and they recommend outer limits for weight loss. The American Academy of Pediatrics31 states: “Weight loss in the infant of greater than 7% from birth weight indicates possible breastfeeding problems and requires more intensive evaluation of breastfeeding and possible intervention to correct problems and improve milk production and transfer.” The International Lactation Consultant Association32 and the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario33 specify that a loss of more than 7% of birth weight, continued loss after day 3, or failure to regain birth weight within a minimum number of days (i.e., 10 days34 or 2–3 weeks,33 respectively) are signs of ineffective breastfeeding. The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine34 advises "Possible indications for supplementation in term, healthy infants [include] weight loss of 8% to 10% accompanied by delayed lactogenesis (day 5 or later).”

These guidelines presume that some weight loss is expected and too much weight loss is a sign of inadequate milk intake due to low milk supply or ineffective milk transfer. The consensus indicates a weight loss in excess of 7% is cause for further assessment and possible intervention. Several of the studies screened for this review are referenced in these CPGs.

Discussion

We found insufficient evidence to answer the question, “What is a normal physiological weight loss for full-term breastfed infants in the first 2 weeks following birth?” We found gaps in relevant data collection and reporting. For instance, weights were not measured daily after discharge and sample size varied within a report due to attrition.

Two difficulties arise when CPGs propose a single, absolute number as the maximum weight an infant can safely lose. First, an absolute number does not take ranges into account. A recommendation based on observations of a mean loss of 7% of birth weight, assuming such recommendations are derived from samples with normal distributions, needs to take standard deviations into account. For example, a mean weight loss of 6.9% with a standard deviation of 3.07, as Maisels et al.24 report in their study, indicates that about 68% of all infants would experience a weight loss of between 4.0% and 9.8%, and that about 95% of all infants would experience a weight loss of between 1.0% and 12.7%.

Second, when distinguishing a physiological from a pathological weight loss, an absolute number may cause health care professionals to miss red flags. For example, a 3-day-old infant with a 7%–10% weight loss is probably reaching his or her lowest weight before gaining, and this child would be in a different situation than a 9-day-old infant who weighs 10% less than his birth weight. Not only has the 9-day-old infant lost weight, but he or she has not regained and is therefore further behind than the 3-day-old infant. An absolute number in this case is deceptive.

Strengths and limitations of the systematic review

The strengths of this review include adherence to a rigorous methodology. For example, 2 researchers independently completed literature searches and abstractions, and follow-up collaboration ensured that the articles were analyzed multiple times. Our group includes experienced clinicians familiar with current lactation research and the issues involved with breastfeeding (e.g., definition of breastfeeding, significance of supplementation) and experts in statistical analysis.

An important limitation of our study was that our research question did not take into account morbidity and mortality. Given the research question and the inclusion criteria established for this systematic review, no studies were specifically sought to provide evidence suggesting a point, by weight or time measurement, when weight loss presents a health risk. We did find that weight loss did not always have clinical indicators. For example, substantial weight losses were not always paired with hypernatremia.11,13,22,29

Identifying what appears to be a normal weight loss leaves the reader with the question, "So, what if weight loss is outside of normal parameters?" It also became apparent as we analyzed the included studies that not all weight loss is physiological: there are demographic and iatrogenic factors that affect weight loss, including feeding and non-feeding factors. The research question and the inclusion criteria for articles sought in this systematic review do not illuminate these factors.

Recommendations for further research.Future research should include measures of morbidity and mortality and consider factors affecting weight loss. Morbidity and mortality rates and their relationship to weight loss must be established to determine the point when interventions are required to prevent illness and protect health. Assessment of effective breastfeeding and decisions about supplementation must be based on more than weight loss. The underlying assumption is that weight loss is directly related to inadequate intake, due to either a lack of milk supply or ineffective milk transfer. There appear to be confounding factors (e.g., factors that are not natural or biological imperatives), as evidenced by the variations in mean weight losses.

We found evidence of patterns of weight loss, but we did not identify a relationship with morbidity or mortality. The data we found did not provide information about the implications of a 7% weight loss or a 10% weight loss. Recognizing weight change patterns helps clinicians identify red flags, but assessment cannot stop there. The implications of the weight loss must be understood. Such evidence would ensure that interventions such as supplementation are not based solely on maintaining an infant’s weight within pre-established norms.

Research is also needed to determine if weight loss is due solely to inadequate intake. There appears to be iatrogenic weight loss, since we found studies that demonstrate that birthing practices, hospital routines, and birth experiences are associated with the amount of weight lost. Researchers should consider the amount of stooling and voiding that might also contribute to neonatal weight loss. For instance, there is some evidence that infants born to mothers who received IV fluids during parturition experience greater weight loss, and excess neonatal diuresis could be the reason.35,36 Studies are needed to understand such factors and how they might affect weight loss.

This systematic review was completed to determine the reference weight loss in the first 2 weeks following birth. Although there is some strong, consistent evidence regarding weight loss patterns in the first few days, the results of our systematic review suggest that further questions need to be answered before a normal range for neonatal physiological weight loss can be established and indications for interventions can be determined.

Biographies

Joy Noel-Weiss, RN, IBCLC, PhD(C), has worked as a registered nurse and lactation consultant in community and hospital settings and is a part-time professor and PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa.

Genevieve Courant, RN(EC), IBCLC, MSc, is a nurse practitioner, a lactation consultant and a part-time faculty member at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine; her practice in Sudbury, Ont., includes a breastfeeding support program.

A. Kirsten Woodend, RN, PhD, is an associate professor, associate dean, and the director of the School of Nursing at the University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: Joy Noel-Weiss and Kirsten Woodend worked on the original concept. Joy and Genevieve Courant completed data collection and data analysis. Joy wrote the first draft and coordinated revisions and approvals of the final published version with both coauthors.

References

- 1.Hartmann P E. Lactation and reproduction in Western Australian women. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(7):543–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Mosby. St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engle William A. A recommendation for the definition of "late preterm" (near-term) and the birth weight-gestational age classification system. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30(1):2–7. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breastfeeding Committee of Canada. Breastfeeding definitions and data collection periods. 2006. http://www.breastfeedingcanada.ca/pdf/BCC%20Breastfeeding%20Def%20and%20Algorithms%20Jan%2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingstone V H, Willis C E, Abdel-Wareth L O, Thiessen P, Lockitch G. Neonatal hypernatremic dehydration associated with breast-feeding malnutrition: a retrospective survey. CMAJ. 2000;162(5):647–52. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10738450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossain MA, Islam MN, Shahidullah M, Akhter H. Pattern of change of weight following birth in the early neonatal period. Mymensingh Med J. 2006;15(1):30–2. doi: 10.3329/mmj.v15i1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jolly PE, Humphrey M, Irons BY, Campbell-Forrester S, Weiss HL. Breast-feeding and weight change in newborns in Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. 2000;26(1):17–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2000.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel M-P, Gremmo-Feger G, Oger E, Sizun J. Pilot study of early breastfeeding difficulties of term newborns: incidence and risk factors. Arch Pediatr. 2007;14(5):454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrago Linda C. The relationship between bowel output and adequacy of breastmilk intake in neonates. Proceedings of the 1996 Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses Conference; 1996; Anaheim, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrago Linda C, Reifsnider Elizabeth, Insel Kathleen. The Neonatal Bowel Output Study: indicators of adequate breast milk intake in neonates. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;32(3):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manganaro R, Mamì C, Marrone T, Marseglia L, Gemelli M. Incidence of dehydration and hypernatremia in exclusively breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 2001;139(5):673–5. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.118880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin-Calama J, Buñuel J, Valero M T, Labay M, Lasarte J J, Valle F, de Miguel C. The effect of feeding glucose water to breastfeeding newborns on weight, body temperature, blood glucose, and breastfeeding duration. J Hum Lact. 1997;13(3):209–13. doi: 10.1177/089033449701300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhat Swarna Rekha, Lewis Patricia, David Angela, Liza Maria. Dehydration and hypernatremia in breast-fed term healthy neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(1):39–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02758258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMarzo S, Seacat J, Neifert M. Initial weight loss and return to birth weight criteria for breast-fed infants: challenging the 'rule of thumb' [conference proceeding] Am J Dis Child. 1991;17(1):31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macdonald PD, Ross SR, Grant L, Young D. Neonatal weight loss in breast and formula fed infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(6):F472–76. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.6.F472. http://fn.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14602693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchini G. Plasma leptin in infants: relations to birth weight and weight loss. Pediatrics. 1998;101:429–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muskinja-Montanji G, Molnar-Sabo I, Vekonj-Fajka G. Physiologic neonatal body weight loss in a "baby friendly hospital". Med Pregl. 1999;52(6-8):237–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodríguez G, Ventura P, Samper M P, Moreno L, Sarría A, Pérez-González J M. Changes in body composition during the initial hours of life in breast-fed healthy term newborns. Biol Neonate. 2000;77(1):12–6. doi: 10.1159/000014189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avoa A, Fischer PR. The influence of perinatal instruction about breast-feeding on neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 1990;86(2):313–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benson S. What is normal? A study of normal breastfeeding dyads during the first sixty hours of life. Breastfeed Rev. 2001;9:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bystrova K, Matthiesen AS, Widstrom AM, Ransjo-Arvidson AB, Welles-Nystrom B, Vorontsov I. 2006. Early Hum Dev. 2006;83(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Çağlar MK, Özer I, Altugan FŞ. Risk factors for excess weight loss and hypernatremia in exclusively breast-fed infants. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(4):539–44. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000400015. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-879X2006000400015&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):607–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12949292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maisels MJ, Gifford K, Antle CE, Leib GR. Jaundice in the healthy newborn infant: a new approach to an old problem. Pediatrics. 1988;81:505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merlob P, Aloni R, Prager H, Jelin N, Idel M, Kotona J. Continued weight loss in the newborn during the third day of life as an indicator of early weaning. Isr J Med Sci. 1994;30(8):646–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers NG, Slusser W. Breastfeeding update 2: Clinical lactation management. Pediatr Rev. 1997;18(5):147–61. doi: 10.1542/pir.18-5-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjon ATW, Kusin JA, deWith WC. Early postnatal growth of Basotho infants in the Mantsonyane area, Lesotho. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1986;6(3):195–8. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1986.11748438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright CM, Parkinson KN. Postnatal weight loss in term infants: what is "normal" and do growth charts allow for it. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89(3):254–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.026906. http://fn.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15102731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaseen H, Salem M, Darwich M. Clinical presentation of hypernatremic dehydration in exclusively breast-fed neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(12):1059–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02829814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program. Washington: National Academy Press; 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amercian Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk policy statement. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Lactation Consultants Association. Clinical guidelines for the establishment of exclusive breastfeeding. Raleigh (NC): ILCA; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Registered Nurses Association of Ontario. Breastfeeding best practice guidelines for nurses. Toronto (ON): RNAO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Protocol #3: Hospital guidelines for the use of supplementary feedings in the healthy term breastfed infant. 3. 2007. http://www.breastfeedingmadesimple.com/bms%20new%20home%20page_files/abm_supplementation.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahlenburg GW, Burnell RH, Braybrook R. The relation between cord serum sodium levels in newborn infants and maternal intravenous therapy during labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87(6):519–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1980.tb04589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merry H, Montgomery A. Do breastfed babies whose mothers have had labor epidurals lose more weight in the first 24 hours of life. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine News and Views. 2000;6:3. [Google Scholar]