Abstract

Background

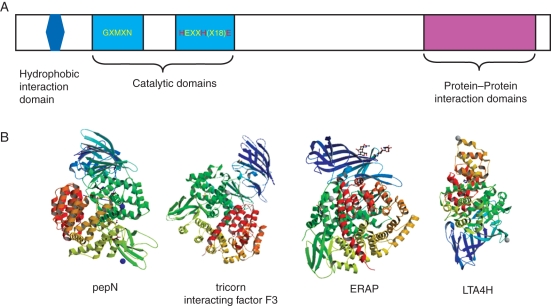

Metallopeptidases of the M1 family are found in all phyla (except viruses) and are important in the cell cycle and normal growth and development. M1s often have spatiotemporal expression patterns which allow for strict regulation of activity. Mutations in the genes encoding M1s result in disease and are often lethal. This family of zinc metallopeptidases all share the catalytic region containing a signature amino acid exopeptidase (GXMXN) and a zinc binding (HEXXH[18X]E) motif. In addition, M1 aminopeptidases often also contain additional membrane association and/or protein interaction motifs. These protein interaction domains may function independently of M1 enzymatic activity and can contribute to multifunctionality of the proteins.

Scope

A brief review of M1 metalloproteases in plants and animals and their roles in the cell cycle is presented. In animals, human puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PSA) acts during mitosis and perhaps meiosis, while the insect homologue puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PAM-1) is required for meiotic and mitotic exit; the remaining human M1 family members appear to play a direct or indirect role in mitosis/cell proliferation. In plants, meiotic prophase aminopeptidase 1 (MPA1) is essential for the first steps in meiosis, and aminopeptidase M1 (APM1) appears to be important in mitosis and cell division.

Conclusions

M1 metalloprotease activity in the cell cycle is conserved across phyla. The activities of the multifunctional M1s, processing small peptides and peptide hormones and contributing to protein trafficking and signal transduction processes, either directly or indirectly impact on the cell cycle. Identification of peptide substrates and interacting protein partners is required to understand M1 function in fertility and normal growth and development in plants.

Key words: Metalloprotease, M1 aminopeptidase, APM1, MPA1, cell cycle, cell division, IRAP, oxytocinase, puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, meiosis, mitosis, root meristem

INTRODUCTION

The cell cycle is an essential process for growth and development of organisms. This highly regulated process involves co-ordination of transcriptional through post-translational mechanisms. A post-translational mechanism that appears to regulate or modulate the cell cycle is the activity of a group of zinc metalloproteases in the M1 family of metalloenzymes. M1 metalloprotease functions include (a) small-peptide processing, often peptide hormones, (b) regulation of cell cycle progression (meiotic or mitotic exit), (c) protein trafficking and (d) signal transduction. Although this group of enzymes is present in all kingdoms, M1 function, i.e. enzymatic targets or interactions with other proteins, in the cell cycle is yet to be defined.

Evidence for M1 function in the cell cycle has been observed in both plant and animal loss-of-function mutants. M1 metalloprotease activity during plant growth and development have recently be observed, with meiotic prophase aminopeptidase (MPA1) important for female and male meiosis and aminopeptidase M1 (APM1) with a putative role in mitosis and cytokinesis. In plants loss-of-function results in decreased fertility from improperly formed gametes (mpa1) and embryo and seedling lethality from cell division arrest (apm1), and similar fertility and embryo lethal phenotypes have been observed in animals. Loss or impaired M1 function in mammals is also correlated with reduced fertility, type-II diabetes and cholesterol uptake. Therefore, these proteins play essential roles in meiosis and mitosis, as well as hormonal or nutrient homeostasis. This brief review will introduce the M1 metalloprotease family, the enzymatic mechanism and known functions, followed by specific examples of M1s in animals and plants and their roles in the cell cycle (Table 1).

Table 1.

M1 metalloproteases presented in this review

| Organism | Name | Peptidase substrate(s) | Non-peptidase function | Cell cycle role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | Aminopeptidase A (APA) | β-Amyloid, cholecystokinin-8, angiotensin II | Unknown | Mitosis |

| Homo sapiens | Aminopeptidase N (APN/CD13) | Angiotensin III, bradykinin, type-IV collagen, MHC class II peptides | Cholesterol uptake, cell surface receptor | Mitosis |

| Drosophilia melanogaster | Aminopeptidase N (APN) | Unknown | Unknown | Mitosis; regulation of cyclin accumulation? |

| Homo sapiens | Insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP) | Oxytocin, vasopressin, angiotensin III, angiotensin IV, MHC type-I peptides | Trafficking | Insulin-dependent mitosis |

| Homo sapiens | Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase (ERAP) | HLA class I peptides | Unknown | Unknown |

| Homo sapiens | Leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) | Unknown | Leukotriene A4 hycrolase (epoxidase activity) | Unknown |

| Homo sapiens | Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PSA) | MHC class I peptides, tau | Unknown | Unknown |

| Mus musculus | Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PSA) | MHC class I peptides | Unknown | Mitosis; male meiosis |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PAM-1) | Cyclin B3? | Unknown | Meiosis and mitosis |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Aminopeptidase M1 (APM1) | Unknown, preference for Tyr peptide substrates in vitro | Trafficking | Mitosis |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Meiotic prophase aminopeptidase 1 (MPA1) | Unknown | Unknown | Male and female meiosis |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Leukotriene A4 hydrolase-like/TAF2-like (2LTA4HL/TAF2L2) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

The M1 family of zinc metalloproteases is distinguished from other M-type proteases by signature amino acid motifs comprising the catalytic region (Medina et al., 1991; Vazeux et al., 1998; Laustsen et al., 2001; Pham et al., 2007). Substrates for this family vary widely, including acidic, basic and neutral amino acid residues. All members of the family process N-terminal amino acids, and cleave either a single amino acid or, less frequently, a series of amino acids. Substrate targets of the M1s tend to be small peptides. Evidence of endopeptidase activity has been shown for a bacterial member of the family, pepN, under stress conditions (Chandu and Nandi, 2003). The M1 metalloproteases are also called gluzincins since they bind a single Zn ion for Zn/water hydrolysis of the substrate. In contrast to other Zn metalloenzymes where the Zn cofactor is co-ordinated by three histidines or by cysteines, the Zn-binding motif of M1 metalloproteases is HEXXH[18X]E, where the two histidines and a distal glutamic acid co-ordinate the Zn ion (Lausten et al., 2001) (Fig. 1A). The proximal glutamic acid is required for water hydrolysis of peptide bonds and subsequent release of the substrate, as demonstrated from mutational analyses (Thompson et al., 2003). The exopeptidase domain GXMXN is the other conserved amino acid motif (Iturrioz et al., 2001). M1 enzymatic activities are regulated by calcium (Goto et al., 2007), and M1 enzymes are characterized by varying degrees of sensitivity to the inhibitor puromycin, which arrests eukaryotic cells in the G2/M phase (Constam et al., 1995).

Fig. 1.

Organization and structures of M1 metallopeptidases. (A) Pictogram of an M1 metalloprotease showing the enzymatic domains (light blue), hydrophobic domain (dark blue) and protein–protein interaction domains (magenta). The zinc-binding amino acids are highlighted in red. (B) Crystal structures (from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Database) of M1 metallopeptidases: Escherichia coli aminopeptidase N (pepN) in complex with phenylalanine (3B34) (Addlagatta et al., 2008); tricorn interacting factor F3 from Thermoplasma acidophilum (1Z5H ) (Kyrieleis et al., 2005); soluble domain of human endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 ERAP1 (2XDT) (Vollmar et al., 2010); LTA4H in complex with Arg-Ala-Arg substrate (3B7T) (Tholander et al., 2008). The zinc ion is represented by a blue (pepN, ERAP) or grey (tricorn F3, LTA4H) sphere.

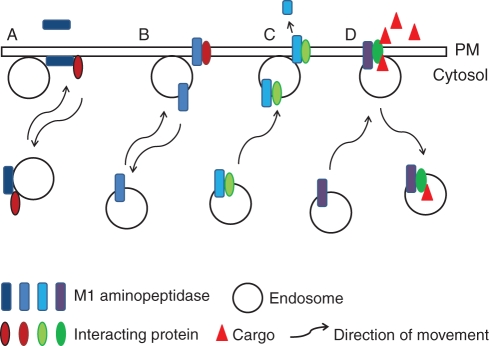

Soluble, membrane-associated, or membrane-anchored M1 peptidases have been identified. Hydrophobic domains in the N-terminus of the proteins can either form a membrane-spanning anchor or a protein–protein interaction domain in peripheral membrane M1 isoforms (Dyer et al., 1990; Cadel et al., 1997; Keller, 2004; Peer et al., 2009). Integral membrane M1s represent a small subset of these enzymes and have the catalytic region exterior to the cell, while the catalytic sites of peripheral membrane proteins are on the cytosolic face. In some instances, the same protein has both soluble and membrane-associated forms (Dyer et al., 1990; Murphy et al., 2002; Peer et al., 2009). Further, some soluble M1s are secreted and, therefore, may be active both inside and outside of the cell (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Models of M1 interactions. (A) A peripheral membrane-associated M1 may be active in the endosomal population and at the plasma membrane (PM). It may also interact with other proteins in the endosome or PM and modulate their functions, such as signal transduction or processing peptides that are exported to or imported from the extracellular space. (B) An integral membrane M1 may have the same activity as a peripheral membrane M1. (C) M1 proteins may also co-traffic proteins to the PM. An example is the insulin-induced IRAP-mediated GLUT4 trafficking to the PM in mammals. (D) M1 proteins may mediate uptake of cargo from the extracellular space via protein-interacting partners. This activity may be independent from their enzymatic activity, such as cholesterol uptake by APN in mammals. M1 proteins may also be secreted into the extracellular space (A) or cleaved and released from the PM (C).

Many M1s function as homodimers, and others form heterodimers with other types of proteins (Hussain et al., 1981; Itoh et al., 1997; Bernier et al., 1998; Matsumoto et al., 2000; Mustafa et al., 2001). C-terminal protein–protein interaction domains often co-ordinate the interactions of M1 oligimerization events. Homodimers may be formed via disulfide linkages or non-covalent interactions (Hesp and Hooper, 1997; Papadopoulos et al., 2001; Ofner and Hooper, 2002). Both integral and peripheral M1s may have additional dileucine protein interaction motifs that function in recycling and retention of the proteins in endosomal populations (Rasmussen et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2001; Katagiri et al., 2002; Cowburn et al., 2006). These motifs are generally found in the C-terminus, although mammalian insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP)/oxytocinase contains a unique N-terminal trafficking domain (Hosaka et al., 2005).

M1s appear to be multi-functional proteins, with some functions related to enzymatic activity and others independent of enzymatic activity (Kramer et al., 2005), although the majority of M1s require an active catalytic domain for function (Albiston et al., 2004; Peer et al., 2009). For example, M1 membrane association, trafficking to the plasma membrane, and M1-mediated trafficking of proteins to the plasma membrane require active catalytic domains (Ofner and Hooper, 2002; Albiston et al., 2004; Hosein et al., 2010). In contrast, cholesterol endocytosis in the intestine involves M1 protein–protein interactions independent of M1 enzymatic activity (Kramer et al., 2005; Fig. 2D).

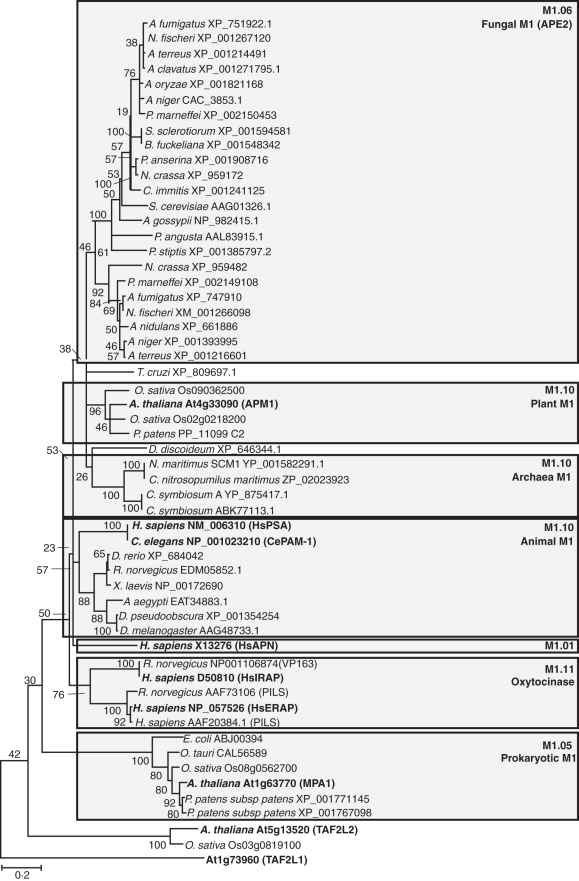

As mentioned above, M1 metalloproteases are found among all kingdoms, except viruses (Fig. 3). Plant, animal and archaea M1s fall into the same clade, with subclades for some animal proteins, such as the oxyocinase family comprised of the insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP/oxytocinase/P-LAP) and the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases (ERAP1/2; Hosein et al., 2010). The fungi form their own clade, as do the prokaryotes (Hosein et al., 2010). Outlying members of the M1 family have homology to other proteins, and therefore are more distantly related. Examples include non-peptidase homologues, such as AC3·5 from Caenorhabditis elegans, while others have dual enzymatic functions, such as human leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H) possessing both aminopeptidase and epoxide hydrolase activities (Thunnissen et al., 2001). The Zn-binding motif is shared between aminopeptidase and epoxide hydrolase activities in LTA4H (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 3.

Dendogram of M1 metalloproteases. Representatives from the different kingdoms are shown based on the MEROPS classification system. Bootstrap values are indicated at branch points. M1 metallopeptidases in bold are discussed in the text. Adapted from Hosein et al. (2010).

ANIMAL M1 METALLOPROTEASES

Both soluble/non-transmembrane and integral membrane M1 metallopeptidases are present in animals. Humans have nine M1s: six transmembrane proteins (aminopeptidase A, aminopeptidase N, insulin-regulated aminopeptidase, endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 and 2 and thyrotropin-releasing hormone-degrading ectoenzyme) with the catalytic domain outside of the cell, and three soluble proteins (puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, aminopeptidase B and leukotriene A4 hydrolase; Tanioka et al., 2003; reviewed in Albiston et al., 2004). Soluble forms of aminopeptidase N (APN) and IRAP have been identified in serum. While thyrotropin-releasing hormone-degrading ectoenzyme has only one substrate, other M1s have multiple substrates, depending on tissue-specific expression as well as subcellular distribution. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase is discussed below in reference to plant M1s; aminopeptidase B shows strong structural similarity to LTA4H, cleaves basic N-terminal amino acids, and can process glucagon into miniglucagon (Fontes et al., 2005; Pham et al., 2007).

APA

Aminopeptidase A (APA), also known as angiotensinase and glutamyl aminopeptidase, is membrane bound and cleaves N-terminal acidic residues, although soluble forms have been found in serum and urine. APA can cleave β-amyloid, which is implicated in Alzheimer's disease (Sevalle et al., 2009). APA is also important in processing signalling peptides, such as the eight-amino acid peptide cholecystokinin-8, which increases nerve growth factor transcription (Migaud et al., 1996). APA cleaves the small eight-amino acid hormone angiotensin II (AngII) to AngIII in the brain (Mitsui et al., 2003), resulting in release of vasopressin which acts in blood pressure regulation. However, in peripheral organs, AngII cleavage may be part of protein metabolism. Inhibition of APA enzymatic activity resulted in inhibition of B precursor cell proliferation (Welch, 1995), and the author suggests that a small peptide inhibitor of B cell proliferation is cleaved by APA, which allows cell proliferation to proceed.

APN

Aminopeptidase N (APN), sometimes called alanyl aminopeptidase or CD13, is a heavily glycosylated protein, and plays a role in regulating blood pressure by converting the seven-amino acid AngIII to AngIV to abrogate the effects of AngIII. APN can process a number of peptide substrates including the kinins (e.g. bradykinin) and type-IV collagen, and generates MHC type-II peptides. However, not all of APN function is dependent on its enzymatic activity. It also appears to act as a receptor and a signalling molecule (reviewed in Mina-Osorio, 2008). However, these functions are likely to include other protein partners.

APN acts as receptor for corona viruses (Kolb et al., 1998; Tusell et al., 2007), and appears to function in cholesterol uptake independent of its enzymatic activity (Wentworth and Holmes, 2001; Kramer et al., 2005). APN endocytosis is regulated by the protein RECK (reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs) (Miki et al., 2007), and trafficking may be a mechanism to regulate APN function at the plasma membrane.

As a signalling molecule, APN mediates release of calcium from intracellular stores and subsequent phosphorylation of specific mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in monocytes (Santos et al., 2000). APN acts as membrane receptor for a 14-3-3σ protein, stratifin, which results in p38 MAPK cascade to stimulate matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression in fibrobasts (Ghaffari et al., 2010). Knockdown of APN resulted in decreased 14-3-3σ binding at the cell surface and decreased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1, which is involved in tumour metastasis. Therefore, APN appears to have a role in cell migration or cell adhesion, also consistent with an enzymatic activity against type-IV collagen.

Another function of APN is suggested from a study in insects. In a genetic screen in Drosopilia, the APN loss-of-function allele slamdance was identified as suppressor of rougheyes in rap/fzr (fizzy-related; Kaplow et al., 2007). FZR is a component of the anaphase-promoting complex, which degrades cyclins during G1 and G2. FZR loss-of function mutants have an extra cell division in the epidermis and endoreduplication is inhibited in salivary glands (Sigrist and Lehner, 1997). Therefore, suppression of the fzr mutant phenotype by the loss of APN suggests that APN may play a role in cell cycle progression by regulating cyclin accumulations. In mammalian monocytes, APN cell surface localization is modulated by the cell cycle, with a decrease observed during S phase (Lohn et al., 2002), and the authors hypothesize, based on inhibition of APN activity by antibodies, that APN acts as a ligand receptor or processes peptides that inhibit cell cycle rates. This is similar to what is seen with respect to proposed APA function in B cell proliferation.

IRAP and ERAPs

The insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP) has many synonyms, including angiotensin IV receptor, cystinyl aminopeptidase, leucyl-cystinyl aminopeptidase, oxytocinase, placental leucine aminopeptidase and vasopressinase, based upon the tissue in which the activity was identified. These were subsequently shown to be the same protein. Soluble IRAP (oxytocinase, placental leucine aminopeptidase, vasopressinase) is found in the serum and regulates the amounts oxytocin and vasopressin during pregnancy in humans, but not in mice (Pham et al., 2009). However, IRAP is usually found as a transmembrane protein localized on the plasma membrane or in endosomal populations.

One specialized endomembrane population of IRAP localizes with glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) in specialized insulin-responsive compartment in adipose and muscle tissue, and IRAP is the only protein known to co-localize with GLUT4 through secretion (Peck et al., 2006) (Fig. 2C). This highly regulated insulin-inducible trafficking of GLUT4 and IRAP to the plasma membrane is mediated by a protein–protein interaction motif in the N-terminus of IRAP with AS160, an Akt with phosphorylation and Rab GTPase activating activity (Peck et al., 2006). Recycling of IRAP from the plasma membrane back to the insulin-responsive compartment requires the Q-SNARE syntaxin 6 (Watson et al., 2008). Targeting of IRAP to the insulin-responsive compartment, both initially, and in retrograde trafficking, is dependent upon one dileuicine motif in the N-terminus (Watson et al., 2008).

Insulin induces IRAP localization to the plasma membrane, where IRAP may cleave small peptide hormones such as oxytocin and vasopressin. In adrenal membranes and brain, IRAP was identified as the AngIV receptor, which regulates blood pressure and learning/memory (Albiston et al., 2003). IRAP can also cleave AngIII to AngIV, which is a competitive inhibitor of IRAP catalytic activity (Lew et al., 2003; Albiston et al., 2004). Therefore, the AngIV cleavage product, produced by APN or IRAP activity, appears to inhibit IRAP activity to rectify the effects of AngIII. Therefore both membrane-bound and soluble IRAP can decrease the effects of AngIII by attenuating the signal and degrading the secreted product. An additional role of IRAP at the plasma membrane may be to cleave cell proliferation inhibitors and promote angiogenesis in tumour cells. IRAP has been shown to increase cell proliferation in endometrial cancer cells (Shibata et al., 2007). The increase in IRAP in tumour cells was concurrent with increases in GLUT4, the insulin receptor and AKT phosphorylation (Shibata et al., 2007).

The endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases, ERAP1 (adipocyte-derived leucine aminopeptidase) and ERAP2 (leukocyte-derived arginine aminopeptidase), form a heterodimer and are involved in post-proteosome processing generation of HLA class I antigenic peptides in immune response (Goldberg et al., 2002; Saveanu et al., 2005), and is not redundant with post-proteosome antigen processing of some IRAP endosomal populations (Goldberg et al., 2002; Georgiadou et al., 2010). In addition, ERAP1 and 2 appear to have a role in pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis, and ERAP1 has been implicated in shedding of cytokine receptors from the cell surface to attenuate signalling (reviewed in Haroon and Inman, 2010).

PSA/PAM-1

The puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase (PSA) from mammals is a soluble protein with both cytosolic and nuclear localization (Constam et al., 1995). Like other M1s, PSA is able to process MHC class I peptides, as well as small peptides, and may have a role in cellular trafficking. PSA associates with microtubules in the spindles during mitosis, and inhibition of PSA also results in apoptosis in the absence of nascent protein synthesis (Constam et al., 1995). In mice, PSA loss-of-function lines have fewer viable embryos resulting in reduced litter size, and are smaller and less fertile, or infertile, compared with wild type, indicating that PSA is required for normal growth (Osada et al., 2001a, b; Towne et al., 2008). However, the target of PSA in cell cycle function is unknown.

The microtubule stabilizing protein tau is an in vitro and in vivo target of PSA which was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for targets of PSA activity (Karsten et al., 2006; Sengupta et al., 2006; Yanagi et al., 2009). Tau degradation by PSA is independent of the proteasome (Sengupta et al., 2006; Yanagi et al., 2009). PSA is localized in neurons, consistent with a role in degrading tau proteins which accumulate in Parkinson's disease.

PAM-1, the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase from C. elegans, is the orthologue of the mammalian PSA (Lyczak et al., 2006), although it is less puromycin sensitive than other M1s (Brooks et al., 2003). PAM-1 loss-of-function mutants are arrested in meiosis. PAM-1 may regulate cyclin B3 activity as inactivation of cyclin B3 in pam-1 rescues the mutant and meiotic exit occurs (Lyczak et al., 2006). PAM-1 is localized at the centrosome during mitosis and is required for oocyte-to-embryo transition and establishment of anterior–posterior (A-P) polarity, although inactivation of cyclin B did not rescue the polarity defect in pam-1 (Lyczak et al., 2006; Fortin et al., 2010). The A-P axis is formed in the single-celled embryo by migration of the sperm-donated centrosomes to signal the posterior axis, which is aberrant in pam-1 mutants (Fortin et al., 2010). When microtubules were inhibited in pam-1, the A-P axis was restored, and cell division proceeded (Fortin et al., 2010). PAM-1 therefore seems to have different targets in meiosis (cyclin B3) and mitosis/A-P axis formation (microtubules, microtubule-associated protein), although a similar phenotype of cell cycle arrest is observed in both cases.

PLANT M1 METALLOPROTEASES

The arabidopsis M1 aminopeptidase family consists of three members (Fig. 3). The bryophyte Physcomitrella patens has one member in the plant/animal/archaea clade, as does Arabidopsis thaliana, whereas a duplication event appears to have occurred following the dicot/monocot split, and Oryza sativa has two members in this clade. In the prokaryotic clade, both rice and arabidopsis have one member each, while P. patens has two members. In an outlying M1 group which is anchored by human TATA box binding protein-associated factor 2 (TAF2), one M1 member is found in rice and arabidopsis (Hosein et al., 2010).

APM1

Aminopeptidase M1 (APM1, At4g33090, GAMEN, HELAH[X18]E) is the single arabidopsis member of the plant/animal/archaea clade. APM1 is a peripheral membrane protein that was identified by its specificity for the non-competitive auxin transport inhibitor N-1-naphthylphthalmic acid (NPA) and the ability to slowly hydrolyse the compound (Murphy and Taiz, 1999a, b; Murphy et al., 2000, 2002, 2005; Smith et al., 2003; Peer et al., 2009; Hosein et al., 2010). The structure of NPA is similar to phthalamide which inhibits M1 activity in animals and plants (Komoda et al., 2001; Murphy et al., 2002; Kakuta et al., 2003). At high concentrations, NPA inhibits APM1 activity, and exhibits increasing inhibition over time (Murphy and Taiz, 1999a; Murphy et al., 2002). Although the mechanism of NPA inhibition of APM1 activity is not known, NPA binds in the active site of APM1, which cleaves the amide bond of NPA. However, the phthalic acid may not be released from the active site or NPA may also bind to an allosteric site in APM1, thereby resulting in an inactive enzyme. NPA binding appears to destabilize APM1, as neither dimers nor monomers are observed after NPA treatment (Hosein et al., 2010).

Enzymatic activity was shown by in vitro assays from purified protein as well as protein expressed in wheat germ extract, rabbit reticulocytes and Escherichia coli (Murphy et al., 2002; Hosein et al., 2010). Although MEROPS classifies APM1 as a cytosol alanyl aminopeptidase, experimentally APM1 shows the greatest metallopeptidase activity against tyrosine residues. The order of activity against small peptide substrates or to amino acid 7-amino-4-trifluoromethyl-coumarin conjugates are Tyr ≫ Ala > Pro ≫ Trp = Leu (Murphy et al., 2002; Hosein et al., 2010). APM1 forms a dimer, and it appears that the dimer is the active form in planta, although the monomer shows enzymatic activity at least equal to that of the dimer in vitro (Murphy et al., 2002; Hosein et al., 2010). APM1 activity is sensitive to puromycin, bestatin, apstatin (substrate mimics) and PAQ-22/PIQ-22 (Murphy, et al., 2002), which binds at an allosteric site and is specific for PSA (Kakuta et al., 2003).

Loss-of-function mutants show embryo lethality and cessation of primary root growth at 5 d after germination (Peer et al., 2009). Site-directed mutagenesis studies have identified amino acid residues and regions of the protein that are essential for its function, as assayed by the ability of the overexpressed mutated construct to rescue the apm1 embryo lethal or root growth arrest phenotypes (Hosein et al., 2010). A β-pleated region in the N-terminus appears to mediate membrane association, and a region of the C-terminus is also essential for APM1 activity. Although mutation of the zinc-binding domain did not rescue any phenotypes, mutation of the exopeptidase domain resulted in partial restoration of embryo lethality in apm1-1, suggesting that exopeptidase activity may be less important during embryo development (Hosein et al., 2010). However, overexpression of a catalytically inactive APM1 in apm1-2, which accumulates a truncated protein missing the C-terminus, rescues the mutant. In addition, the same results are obtained when apm1 mutants are transformed with catalytically active or inactive IRAP, also indicating conservation of M1 function across kingdoms. These results also indicate that one intact copy of the catalytic domain and one intact copy of the C-terminus are required for APM1 function, and that the domains need not be in the same linear molecule (Hosein et al., 2010). As mentioned above, the C-terminus of M1s often have protein interaction motifs. The C-terminus of APM1 may be important for its dimerization or interaction with other proteins. Candidate proteins with which APM1 may interact were identified via co-purification (Murphy et al., 2002), and co-immunoprecipitation, yeast two-hybrid, yeast three-hybrid and split-ubiquitin assays. However, more experiments are needed to conclude which proteins interact with APM1 and which proteins are substrate targets.

Diacidic motif scanning identified one dileucine pair (of 13) that is required for APM1 function (Hosein et al., 2010). Dileucines are part of endocytosis motifs [ED]XXXL[LI] recognized by the adaptor protein complexes and are important in targeting proteins to organelles (Hou et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2008). This dileucine motif is proximal to the essential region of the C-terminus mentioned above. APM1 is enriched in light membrane microsomal fractions and shows localization in endosomes, the plasma membrane and at the forming cell plate, consistent with a hydrophobic region in the N-terminus (Murphy et al., 2002; Peer et al., 2009, Hosein et al., 2010). Additional evidence supporting that APM1 trafficks to and from the plasma membrane is provided by electron microscopy immunolocalizations (Peer et al., 2009). APM1 also co-purified with adaptor protein subunits, as well as plasma membrane localized auxin transporters (Murphy et al., 2002). APM1 loss-of-function lines show mistargeting of PIN2 and ABCB19 transporters to the plasma membrane (Peer et al., 2009). APM1 subcellular localization, shown by immunolocalizations and functional fluorescent-protein fusions, is sensitive to the trafficking inhibitors that affect PIN2 localization (Peer et al., 2009).

As mentioned above, APM1 loss-of-function lines exhibit root growth arrest 5 d after germination, the peak time of APM1 expression. Root growth arrest can be attributed to (a) premature determinacy of the root meristem, as shown by cessation of quiescent centre activity, and (b) cell cycle arrest, as shown by absence of cyclinB1;1 expression (Peer et al., 2009). Several factors maintain the quiescent centre including non-cell autonomous transcription factors (e.g. SHORTROOT, SCARECROW), mobile small peptide hormones (e.g. CLAVATA3/ESR-related CLE proteins), and the hormone auxin. SHR and SCR are misexpressed or mislocalized in apm1 lines, resulting in mis-specification of the ground tissue (Peer et al., 2009). APM1 expression increases in the presence of auxin in a two-stage manner, suggesting both a primary auxin response and a secondary response which is usually associated with wounding or defence (Peer et al., 2009), and the promoter contains an auxin-responsive element (TGTCAT; Donner et al., 2009), consistent with increased expression following auxin application. A putative zinc carboxypeptidase SOL1 was identified in a CLE19 overexpression screen, suggesting that CLE may be activated by SOL1 activity (Casamitjana-Martínez et al., 2003). Although the substrate(s) for APM1 are yet to be identified, one of the CLE proteins is a possible candidate for activation/deactivation by APM1. The absence of cyclinB1;1 expression in the apm1-1 suggests that the mutants may be arrested in G2/M or never reached that stage (Peer et al., 2009). The APM1 promoter contains signature sequences associated with cell cycle regulation (GCCCR; Banchio et al., 2003), supporting that APM1 expression may be tied to the cell cycle. At least two other M1 metalloproteases have been implicated in meiotic or mitotic exit (PSA and PAM-1), while APN may regulate or act as a component of the anaphase-promoting complex. Therefore, it seems likely that APM1 may also play a role in cell cycle progression that is yet to be elucidated.

APM1 also appears to be involved in cytokinesis. Immuno- and functional fluorescent-protein fusion localizations of APM1 show signals at the forming cell plate, apparently at the leading edges (Peer et al., 2009). Loss-of-function mutants show irregular planes of cell division in mutants, supporting a role for APM1 in cell division (Peer et al., 2009). Since the planes of cell division are mis-specified, APM1 may play a role in polarity with respect to placement of the pre-prophase band, in addition to a role in cell plate formation.

Immunolocalizations show APM1 signals in the maturing xylem elements while loss-of-function mutant show mis-specification of ground tissue and irregular vasculature (Peer et al., 2009). Northern blot (Murphy et al., 2002) and microarray analyses (Genevestigator, eFPBorwser) show that APM1 is also highly expressed in senescing leaves. The end result of xylem maturation and senescence is dead cells. This suggests a role for APM1 in programmed cell death; either a direct role in apoptosis or a role in recycling of proteins/amino acids in this process is yet to be determined.

MPA1

Meiotic prophase aminopeptidase 1 (MPA1, At1g63770, GAMEN, HEYFH[X18]E) is the single M1 arabidopsis member of the prokaryotic clade (Hosein et al., 2010), and MEROPS places it as bacterial-type alanyl aminopeptidase. Unlike APM1 and TAF2L2/LTA4HL (see below) which have one gene model each, MPA1 has four different gene models, suggesting the possibility of spatio-temperal regulation. Based on amino acid motif analysis, MPA1 appears to be a soluble protein that lacks the N-terminal hydrophobic and C-terminal protein–protein interaction domains present in APM1. The enzymatic activity of MPA1 has not been described; however, treatment of inflorescences with a fluorescent version of the M1 inhibitor PAQ22 phenocopied a meiotic defect observed in the loss-of-function mutant (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004). The semi-sterile phenotype was also attributed to inhibition of MPA1 activity (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004), but the observed embryo abortion was likely an aggregation of inhibition of MPA1 during gametogenesis and APM1 during embryogenesis.

MPA1 appears to regulate cell cycle progression during meiosis in both female and male gametophytes (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004). In mpa1, a combination of defects is observed during meiosis, beginning with abnormal synapsis. Incomplete synapsis occurred 4-fold more frequently than wild type with a 90 % decrease in homologous crossovers, and the chromosome pairs were not linked by chiasmata (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004). In mpa1, the recombination protein RAD51 is destabilized and the mismatch repair protein MSH1 is mislocalized (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004), resulting in high disjunction frequencies during anaphase I for chromosomes 2, 4 and 5 which carries over through meiosis II (Pradillo et al., 2007). However, spindle formation appears to be normal in mpa1 mutants (Sánchez-Morán et al., 2004). One possible scenario is that MPA1 is necessary for synaptonemal complex formation and subsequent dissociation.

MPA1 is expressed in somatic tissues as well (Genevestigator, eFPBowser), and MPA1 appears to be a cytosolic protein that is also normally present in the apoplast (Kaffarnik et al., 2009). Proteomics of the arabidopsis extracellular space following Pseudomonas syringae infection indicates that abundance of MPA1 in the apoplast was increased by type-III effectors (TTEs) but decreased by microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) as well as gene-for-gene resistance (Kaffarnik et al., 2009). Bacterial MAMPs, e.g. flagellin, induce the basal defence system in plants via a receptor-like kinase-mediated signal transduction cascade. Bacterial TTEs overcome the MAMP-activated resistance by affecting cellular responses, from mitogen-activated protein kinases (Zhang et al., 2007) to RNA metabolism (Fu et al., 2007). The MAMP-associated decrease in apoplastic MPA1 may be either through bacterial degradation of MPA1 or suppression of MPA1 secretion (Kaffarnik et al., 2009). The presence of MPA1 outside of the cell suggests that MPA1 may also have a role in basal defence responses or modification of extracellular peptides. Increased extracellular MPA1 accumulation by TTEs suggests that MPA1 activity provides metabolic products for the pathogen.

TAF2L/LTA4HL

A TAF2-like 2 (TAF2L2)/leukotriene A4 hydrolase-like (LTA4HL) gene is found in arabidopsis (At5g13520, GGMEN, HELAH[X18]E). The function(s) of this protein is unknown. MEROPS places it as cold-active aminopeptidase (Colwellia psychrerythraea)-type peptidase. Aminopeptidase activity has been reported for this protein (Walling, 2006), but LTA4H/epoxide hydrolase activity has not been examined. In animals, leukotrienes are fatty acids that are lipid signalling molecules acting via G-coupled protein receptors (Haeggström, 2000), and plant compounds are used therapeutically to inhibit leukotriene synthesis/activity (Adams and Bauer, 2008). Plants are not considered to synthesize leukotrienes (nor the arachidonic acid precursor), although there is one report of LTB4 and LTC4 accumulation in nettle glandular trichomes (Czarnetzki et al., 1990). Epoxide hydrolases in plants are associated with conversion of fatty acids stores in seeds and synthesis of cutins for defence (Stark et al., 1995; Blée and Schuber, 1993). Leukotrienes are synthesized by a complex of enzymes, with the soluble LTA4H having both cytosolic and nuclear localization (Newcomer and Gilbert, 2010). A biological function for human LTA4H aminopeptidase activity has not been demonstrated. Overexpression (35S) constructs of At5g13520 show nuclear localization, as well as cytosolic localization (Hosein et al., 2010). At5g13520 was expressed in the apm1-3 loss-of-function lines which showed heterodimerzation of the mutant APM1 protein and TAF2L2/LTA4HL, with the observed cytosolic localization attributed to the herterodimer (Hosein et al., 2010). That being said, more research needs to be conducted with native promoters, and the subcellular localization suggests that this protein may be involved in (a) processing transcription factor-associated proteins or small peptide hormones in the nucleus and/or (b) fatty acid biosynthesis/metabolism.

Like C. elegans AC3·5, arabidopsis has a non-peptidase M1 homologue (At1g73960, TAF2L1), which is in the TAF2 group (MEROPS). TAF2L1 has two different gene models and its function is unknown.

CONSERVATION OF FUNCTION AND ROLES OF PLANT M1 METALLOPROTEASES

M1 metalloproteaes appear to be multifunctional proteins, and their functions are required for normal cell growth and activity. M1 enzymatic function is required for cell cycle regulation in both meiosis and mitosis and for processing small peptides, such as hormones, for growth and antigens for defence. M1s can function as classical receptors and participants in signal transduction. They participate in cellular trafficking of transporters, directly or indirectly, and sterols. Some of M1 function in these processes is dependent on microtubule associations or degradation of microtubule-associated proteins. However, it is unclear if M1 function is independent of catalytic activity due to the small number of studies of enzymatically inactive proteins. These studies are difficult as loss-of-function is often lethal.

Post-proteasome and proteasome-independent peptide processing have been demonstrated in animals, but proteasome-associated peptide processing has not been directly observed. M1 aminopeptidases in plants may be associated with the proteasome/anaphase-promoting complex. The anaphase-promoting complex itself has been shown to have a dual function. For example, arabidopsis CDC27B/HOBBIT functions in the anaphase-promoting complex in gametogenesis, mitosis (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2008) and regulation of plant defence responses (Kudo et al., 2007).

Conservation of function between the plant and animal kingdoms is demonstrated by the ability of IRAP to rescue apm1 embryo and growth defects. An hypothesis of APM1 function was based on hormone-induced trafficking of a transporter to the plasma membrane, i.e. auxin-induced trafficking of APM1 and an auxin transporter to the plasma membrane as an analogue of insulin-induced trafficking of IRAP and GLUT4 to the plasma membrane. This model was based on co-purification of APM1 with auxin transporters and trafficking components (Muday and Murphy, 2002; Murphy et al., 2002; Muday et al., 2003). Although this hypothesis has not been fully tested, it appears that APM1 effects on auxin transporter localization are indirect (Peer et al., 2009). It seems more likely that APM1 may function like APN or PSA/PAM-1.

The role of APM1 in the switch between an indeterminate and determinate root meristem may lie in nutritional homeostasis, small-peptide processing or anaphase-promoting complex activity or a combination of the above. A potential role of APM1 in nutritional homeostasis may lie in N-terminal peptide processing, perhaps as part of the proteasome, to supply the free amino acid pools for de novo protein synthesis or nitrogen availability for growth. Small peptide hormones and signalling molecules, e.g. CLE, have been shown to regulate and maintain the meristem and occur as gradients in the root with some CLE proteins promoting meristem maintenance and others vascular differentiation via phospholipid signalling (Hirakawa et al., 2008; Whitford et al., 2008; Gagne and Clark, 2010; Meng et al., 2010). Since overexpression or exogenous application of CLE results in root meristem consumption (Fiers et al., 2005; Ito et al., 2006), APM1 may serve to attenuate the signal. APM1 activity could also attenuate tracheary element differentiation inhibitory factors which share sequence identity with CLEs (Ito et al., 2006). This hypothesis is consistent with APM1 localization pattern, the apm1 mutant phenotypes and tissue-specific substrates observed for animal M1 metalloproteases. The APM1 promoter contains three GCCCR elements, indicating that its expression is regulated by the cell cycle, and it may regulate cell cycle checkpoints as does PSA. MPA1 activity in meiosis appears to be clear, although the substrate and mechanism of its action is not known, while the function of extracellular MPA1 is unknown. The function of TAF2L2/LTA4HL is also unknown. Many outstanding questions remain, which can only begin to be answered when both peptide substrates and protein partners for M1 metalloproteases are identified.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Efforts to identify aminopeptidase substrates in plants have been unsatisfactory due to lack of technological advances required to identify products of single amino acid hydrolysis from peptides in planta. Proteomics approaches, such as two-dimensional electrophoresis, cannot distinguish such small changes. In addition, the activity of the aminopeptidase may be followed by other hydrolytic events, thereby obscuring the aminopeptidase activity of interest. Protease inhibitors, such as MG132 which is specific for the proteosome, have been used to distinguish between proteosome-dependent and -independent activities. Combinations of protease inhibitors have also been used, but these are not always specific, and then definitive results cannot be obtained. For example, bestatin is a strong inhibitor of M24 metalloproteases and M1s to a lesser extent, therefore an inhibited M1 activity may be incorrectly attributed to M24. The sensitivity of M1s to inhibitors should be revisited which would better inform this approach. An approach that may be more fruitful is to change the enzyme into a substrate-binding protein without catalytic activity. This should lead to identification of physiologically relevant substrates from plant cell extracts. Understanding the function of APM1 and MPA1 in the cell cycle in plants has clear implications for understanding of M1 function in the cell cycle and development in other organisms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Angus Murphy for his support and encouragement, our on-going collaboration, and for helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was funded by NSF-IOS 0820648.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams M, Bauer R. Inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis by secondary plant metabolites. Current Organic Chemistry. 2008;12:602–618. [Google Scholar]

- Addlagatta A, Gay L, Matthews BW. Structural basis for the unusual specificity of Escherichia coli aminopeptidase N. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5303–5311. doi: 10.1021/bi7022333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiston AL, Mustafa T, McDowall SG, Mendelsohn FA, Lee J, Chai SY. AT4 receptor is insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase: potential mechanisms of memory enhancement. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2003;14:72–77. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiston AL, Ye S, Chai SY. Membrane bound members of the M1 family: more than aminopeptidases. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2004;11:491–500. doi: 10.2174/0929866043406643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchio C, Schang LM, Vance DE. Activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase alpha expression during the S phase of the cell cycle is mediated by the transcription factor Sp1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:32457–32464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier SG, Bellemare JM, Escher E, Guillemette G. Characterization of AT4 receptor from bovine aortic endothelium with photosensitive analogues of angiotensin IV. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4280–4287. doi: 10.1021/bi972863j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blée E, Schuber F. Biosynthesis of cutin monomers: involvement of a lipoxygenase/peroxygenase pathway. The Plant Journal. 1993;4:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DR, Hooper NM, Isaac RE. The Caenorhabditis elegans orthologue of mammalian puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase has roles in embryogenesis and reproduction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:42795–42801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadel S, Foulon T, Viron A, et al. Aminopeptidase B from the rat testis is a bifunctional enzyme structurally related to leukotriene-A4 hydrolase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:2963–2968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamitjana-Martínez E, Hofhuis HF, Xu J, Liu CM, Heidstra R, Scheres B. Root-specific CLE19 overexpression and the sol1/2 suppressors implicate a CLV-like pathway in the control of Arabidopsis root meristem maintenance. Current Biology. 2003;13:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandu D, Nandi D. PepN is the major aminopeptidase in Escherichia coli: insights on substrate specificity and role during sodium-salicylate-induced stress. Microbiology. 2003;149:3437–3447. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constam DB, Tobler AR, Rensing-Ehl A, Kemler I, Hersh LB, Fontana A. Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase: sequence analysis, expression, and functional characterization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:26931–26939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn AS, Sobolewski A, Reed BJ, et al. Aminopeptidase N (CD13) regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in human neutrophils. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:12458–12467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnetzki BM, Thiele T, Rosenbach T. Immunoreactive leukotrienes in nettle plants (Urtica urens) International Archives of Allergy and Applied Immunology. 1990;91:43–46. doi: 10.1159/000235087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner TJ, Sherr I, Scarpella E. Regulation of preprocambial cell state acquisition by auxin signaling in Arabidopsis leaves. Development. 2009;136:3235–3246. doi: 10.1242/dev.037028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer SH, Slaughter CA, Orth K, Moomaw CR, Hersh LB. Comparison of the soluble and membrane-bound forms of the puromycin-sensitive enkephalin-degrading aminopeptidases from rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1990;54:547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers M, Golemiec E, Xu J, et al. The 14-amino acid CLV3, CLE19, and CLE40 peptides trigger consumption of the root meristem in Arabidopsis through a CLAVATA2-dependent pathway. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2542–2553. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes G, Lajoix AD, Bergeron F, et al. Miniglucagon-generating endopeptidase, which processes glucagon into miniglucagon, is composed of NRD convertase and aminopeptidase B. Endocrinology. 2005;146:702–712. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin SM, Marshall SL, Jaeger EC, et al. The PAM-1 aminopeptidase regulates centrosome positioning to ensure anterior-posterior axis specification in one-cell C. elegans embryos. Developmental Biology. 2010;344:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu ZQ, Guo M, Jeong BR, et al. A type III effector ADP-ribosylates RNA-binding proteins and quells plant immunity. Nature. 2007;447:284–288. doi: 10.1038/nature05737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JM, Clark SE. The Arabidopsis stem cell factor POLTERGEIST is membrane localized and phospholipid stimulated. The Plant Cell. 2010;22:729–743. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou D, Hearn A, Evnouchidou I, et al. Placental leucine aminopeptidase efficiently generates mature antigenic peptides in vitro but in patterns distinct from endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185:1584–1592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari A, Li Y, Kilani RT, Ghahary A. 14-3-3σ associates with cell surface aminopeptidase N in the regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-1. Journal of Cell Science. 2010;123:2996–3005. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AL, Cascio P, Saric T, Rock KL. The importance of the proteasome and subsequent proteolytic steps in the generation of antigenic peptides. Molecular Immunology. 2002;39:147–164. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y, Hattori A, Mizutani S, Tsujimoto M. Asparatic acid 221 is critical in the calcium-induced modulation of the enzymatic activity of human aminopeptidase A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:37074–37081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeggström JZ. Structure, function, and regulation of leukotriene A4 hydrolase. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;161:S25–S31. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_1.ltta-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon N, Inman RD. Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidases: biology and pathogenic potential. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y, Shinohara H, Kondo Y, et al. Non-cell-autonomous control of vascular stem cell fate by a CLE peptide/receptor system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2008;105:15208–15213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808444105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesp JR, Hooper NM. Proteolytic fragmentation reveals the oligomeric and domain structure of porcine aminopeptidase A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3000–3007. doi: 10.1021/bi962401q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka T, Brooks CC, Presman E, et al. p115 interacts with the GLUT4 vesicle protein, IRAP, and plays a critical role in insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16:2882–2890. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosein FN, Bandyopadhyay A, Peer WA, Murphy AS. The catalytic and protein–protein interaction domains are required for APM1 function. Plant Physiology. 2010;152:2158–2172. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.148742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou JC, Suzuki N, Pessin JE, Watson RT. A specific dileucine motif is required for the GGA-dependent entry of newly synthesized insulin-responsive aminopeptidase into the insulin-responsive compartment. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:33457–33466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MM, Tranum-Jensen J, Noren O, Sjostrom H, Christiansen K. Reconstitution of purified amphiphilic pig intestinal microvillus aminopeptidase: mode of membrane insertion and morphology. Biochemistry Journal. 1981;199:179–186. doi: 10.1042/bj1990179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Nakanomyo I, Motose H, et al. Dodeca-CLE peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science. 2006;313:842–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1128436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh C, Watanabe M, Nagamatsu A, Soeda S, Kawarabayashi T, Shimeno H. Two molecular species of oxytocinase (L-cystine aminopeptidase) in human placenta: purification and characterization. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1997;20:20–24. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz X, Rozenfeld R, Michaud A, Corvol P, Llorence-Cortes C. Study of asparagine 353 in aminopeptidase A: characterization of a novel motif (GAMEN) implicated in exopeptidase specificity of monozinc aminopeptidases. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14440–14448. doi: 10.1021/bi011409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AO, Lampson MA, McGraw TE. A di-leucine sequence and a cluster of acidic amino acids are required for dynamic retention in the endosomal recycling compartment of fibroblasts. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2001;12:367–381. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffarnik FA, Jones AM, Rathjen JP, Peck SC. Effector proteins of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae alter the extracellular proteome of the host plant. Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2009;8:145–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800043-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuta H, Tanatani A, Nagasawa K, Hashimoto Y. Specific nonpeptide inhibitors of puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase with a 2,4 (1H,3H)-quinazolinedione skeleton. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2003;55:1273–1282. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow ME, Mannava LJ, Pimentel AC, et al. A genetic modifier screen identifies multiple genes that interact with Drosophila Rap/Fzr and suggests novel cellular roles. Journal of Neurogenetics. 2007;21:105–151. doi: 10.1080/01677060701503140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten SL, Sang TK, Gehman LT, et al. A genomic screen for modifiers of tauopathy identifies puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase as an inhibitor of tau-induced neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2006;51:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri H, Asano T, Yamada T, et al. Acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenases are localized on GLUT4-containing vesicles via association with insulin-regulated aminopeptidase in a manner dependent on its dileucine motif. Molecular Endcrinology. 2002;16:1049–1059. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SK. Role of the insulin-regulated aminopeptidase IRAP in insulin action and diabetes. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2004;27:761–764. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BT, McCoy AJ, Späte K, et al. A structural explanation for the binding of endocytic dileucine motifs by the AP2 complex. Nature. 2008;456:976–979. doi: 10.1038/nature07422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb AF, Hegyi A, Maile J, Heister A, Hagemann M, Siddell SG. Molecular analysis of the coronavirus-receptor function of aminopeptidase N. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1998;440:61–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komoda M, Kakuta H, Takahashi H, et al. Specific inhibitor of puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase with a homophthalimide skeleton: identification of the target molecule and a structure-activity relationship study. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;9:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer W, Girbig F, Corsiero D, et al. Aminopeptidase N (CD13) is a molecular target of the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe in the enterocyte brush border membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:1306–1320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo C, Suzuki T, Fukuoka S, et al. Suppression of Cdc27B expression induces plant defence responses. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2007;8:365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrieleis OJP, Goettig P, Kiefersauer R, Huber R, Brandstetter H. Crystal structures of the Tricorn interacting factor F3 from Thermoplasma acidophilum, a zinc aminopeptidase in three different conformations. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;349:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lausten PG, Vang S, Kristensen T. Mutational analysis of the active site of human insulin-regulated aminopeptidase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268:98–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew RA, Mustafa T, Ye S, McDowall SG, Chai SY, Albiston AL. Angiotensin AT4 ligands are potent, competitive inhibitors of insulin regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP) Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;86:344–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohn M, Mueller C, Langner J. Cell cycle retardation in monocytoid cells induced by aminopeptidase N (CD13) Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2002;43:407–413. doi: 10.1080/10428190290006233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyczak R, Zweier L, Group T, et al. The puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase PAM-1 is required for meiotic exit and anteroposterior polarity in the one-cell Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Development. 2006;133:4281–4292. doi: 10.1242/dev.02615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Rogi T, Yamashiro K, et al. Characterization of a recombinant soluble form of human placental leucine aminopeptidase/oxytocinase expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2000;267:46–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Rådmark O, Funk CD, Haeggström JZ. Molecular cloning and expression of mouse leukotriene A4 hydrolase cDNA. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1991;176:1516–1524. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90459-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, Ruth KC, Fletcher JC, Feldman L. The roles of different CLE domains in Arabidopsis CLE polypeptide activity and functional specificity. Molecular Plant. 2010;3:760–772. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud M, Durieux C, Viereck J, Soroca-Lucas E, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques BP. The in vivo metabolism of cholecystokinin (CCK-8) is essentially ensured by aminopeptidase A. Peptides. 1996;17:601–607. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Takegami Y, Okawa K, Muraguchi T, Noda M, Takahashi C. The reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs (RECK) interacts with membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase and CD13/aminopeptidase N and modulates their endocytic pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:12341–12352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina-Osorio P. The moonlighting enzyme CD13: old and new functions to target. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2008;14:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui T, Nomura S, Okada M, et al. Hypertension and angiotensin II hypersensitivity in aminopeptidase A-deficient mice. Molecular Medicine. 2003;9:57–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muday GK, Murphy AS. An emerging model of auxin transport regulation. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:293–299. doi: 10.1105/tpc.140230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muday GK, Peer WA, Murphy AS. Vesicular cycling mechanisms that control auxin transport polarity. T. rends in Plant Science. 2003;8:301–304. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Taiz L. Localization and characterization of soluble and plasma membrane aminopeptidase activities in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 1999a;37:431–443. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Taiz L. Naphthylphthalamic acid is enzymatically hydrolyzed at the hypocotyl-root transition zone and other tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 1999b;37:413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A, Peer WA, Taiz L. Regulation of auxin transport by aminopeptidases and endogenous flavonoids. Planta. 2000;211:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s004250000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AS, Hoogner KR, Peer WA, Tai L. Identification, purification, and molecular cloning of N-1-naphthylphthalmic acid-binding plasma membrane-associated aminopeptidases from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2002;128:935–950. doi: 10.1104/pp.010519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AS, Bandyopadhyay A, Holstein SE, Peer WA. Endocytotic cycling of PM proteins. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2005;56:221–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa T, Chai SY, Mendelsohn FA, Moeller I, Albiston AL. Characterization of the AT4 receptor in a human neuroblastoma cell line (SK-N-MC) Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;76:1679–1687. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer ME, Gilbert NC. Location, location, location: compartmentalization of early events in leukotriene biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:25109–25114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.125880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofner LD, Hooper NM. The C-terminus domain, but not the interchain disulphide, is required for the activity and intracellular trafficking of aminopeptidase A. Biochemistry Journal. 2002;362:191–197. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada T, Watanabe G, Sakaki Y, Takeuchi T. Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase is essential for the maternal recognition of pregnancy in mice. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001a;15:882–893. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.6.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada T, Watanabe G, Kondo S, Toyoda M, Sakaki Y, Takeuchi T. Male reproductive defects caused by puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase deficiency in mice. Molecular Endocrinology. 2001b;15:960–971. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.6.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos T, Kelly JA, Bauer K. Mutational analysis of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone-degrading ectoenzyme: similarities and differences with other members of the M1 family of aminopeptidases and thermolysin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9347–9355. doi: 10.1021/bi010695w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck GR, Ye S, Pham V, et al. Interaction of the Akt substrate, AS160, with the glucose transporter 4 vesicle marker protein, insulin-regulated aminopeptidase. Molecular Endocrinology. 2006;20:2576–2583. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer WA, Hosein FN, Bandyopadhyay A, et al. Mutation of the membrane-associated M1 protease APM1 results in distinct embryonic and seedling developmental defects in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:1693–1721. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez JM, Serralbo O, Vanstraelen M, et al. Specialization of CDC27 function in the Arabidopsis thaliana anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) The Plant Journal. 2008;53:78–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham V, Burns P, Albiston AL, et al. Reproduction and maternal behavior in insulin-regulated aminopeptidase (IRAP) knockout mice. Peptides. 2009;30:1861–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham VL, Cadel MS, Gouzy-Darmon C, et al. Aminopeptidase B, a glucagon-processing enzyme: site directed mutagenesis of the Zn2+-binding motif and molecular modelling. BMC Biochemistry. 2007;8:21–41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradillo M, López E, Romero C, Sánchez-Morán E, Cuñado N, Santos JL. An analysis of univalent segregation in meiotic mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana: a possible role for synaptonemal complex. Genetics. 2007;175:505–511. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.067595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen TE, Pedraza-Diaz S, Hardre R, Laustsen PG, Carrion AG, Kristensen T. Structure of the human oxytocinase/insulin-regulated aminopeptidase gene and localization to chromosome 5q21. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2000;267:2297–2306. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Morán E, Jones GH, Franklin FC, Santos JL. A puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase is essential for meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:2895–2909. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AN, Langner J, Herrmann M, Riemann D. Aminopeptidase N/CD13 is directly linked to signal transduction pathways in monocytes. Cellular Immunology. 2000;20:22–32. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saveanu L, Carroll O, Lindo V, et al. Concerted peptide trimming by human ERAP1 and ERAP2 aminopeptidase complexes in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature Immunology. 2005;6:689–697. doi: 10.1038/ni1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Horowitz PM, Karsten SL, et al. Degradation of tau protein by puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase in vitro. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15111–15119. doi: 10.1021/bi061830d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevalle J, Amoyel A, Robert P, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Roques B, Checler F. Aminopeptidase A contributes to the N-terminal truncation of amyloid beta-peptide. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;109:248–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K, Kajiyama H, Ino K, et al. P-LAP/IRAP-induced cell proliferation and glucose uptake in endometrial carcinoma cells via insulin receptor signaling. BMC Cancer. 2007;7(15) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-15. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist SJ, Lehner CF. Drosophila fizzy-related down-regulates mitotic cyclins and is required for cell proliferation arrest and entry into endocycles. Cell. 1997;90:671–681. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AP, Nourizadeh SD, Peer WA, et al. Arabidopsis AtGSTF2 is regulated by ethylene and auxin, and encodes a glutathione S-transferase that interacts with flavonoids. The Plant Journal. 2003;36:433–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Lundholm AK, Meijer J. Comparison of fatty acid epoxide hydrolase activity in seeds from different plant species. Phytochemistry. 1995;38:31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tanioka T, Hattori A, Masuda S, et al. Human leukocyte-derived arginine aminopeptidase: the third member of the oxytocinase subfamily of aminopeptidases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:32275–32283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholander F, Muroya A, Roques BP, et al. Structure-based dissection of the active site chemistry of leukotriene A4 hydrolase: implications for M1 aminopeptidases and inhibitor design. Chemistry & Biology. 2008;15:920–929. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MW, Govindaswami M, Hersh LB. Mutation of active site residues of the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase: conversion of the enzyme into a catalytically inactive binding protein. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2003;413:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thunnissen MM, Nordlund P, Haeggstrom JZ. Crystal structure of human leukotriene A(4) hydrolase, a bifunctional enzyme in inflammation. Nature Structural Biology. 2001;8:131–135. doi: 10.1038/84117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towne CF, York IA, Neijssen J, et al. Puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase limits MHC class I presentation in dendritic cells but does not affect CD8 T cell responses during viral infections. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:1704–1712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusell SM, Schittone SA, Holmes KV. Mutational analysis of aminopeptidase N, a receptor for several group 1 coronaviruses, identifies key determinants of viral host range. Journal of Virology. 2007;81:1261–1273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01510-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazeux G, Iturrioz X, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. A glutamate residue contributes to the exopeptidase specificity in aminopeptidase A. Biochemistry Journal. 1998;334:407–413. doi: 10.1042/bj3340407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmar M, Kochan G, Krojer T, et al. Crystal structure of the soluble domain of human endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 ERAP1. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 2010 http://www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do . doi:10.2210/pdb2xdt/pdb. [Google Scholar]

- Walling LL. Recycling or regulation? The role of amino-terminal modifying enzymes. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2006;9:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson RT, Hou JC, Pessin JE. Recycling of IRAP from the plasma membrane back to the insulin-responsive compartment requires the Q-SNARE syntaxin 6 but not the GGA adaptors. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121:1243–1251. doi: 10.1242/jcs.017517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch PA. Regulation of B-cell precursor proliferation by aminopeptidase-A. International Immunology. 1995;7:737–746. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth DE, Holmes KV. Molecular determinants of species specificity in the coronavirus receptor aminopeptidase N (CD13): influence of N-linked glycosylation. Journal of Virology. 2001;75:9741–9752. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9741-9752.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford R, Fernandez A, De Groodt R, Ortega E, Hilson P. Plant CLE peptides from two distinct functional classes synergistically induce division of vascular cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2008;105:18625–18630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809395105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi K, Tanaka T, Kato K, et al. Involvement of puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase in proteolysis of tau protein in cultured cells, and attenuated proteolysis of frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) mutant tau. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9:157–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shao F, Li Y, et al. A Pseudomonas syringae effector inactivates MAPKs to suppress PAMP-induced immunity in plants. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;1:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]